User login

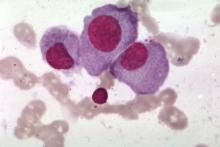

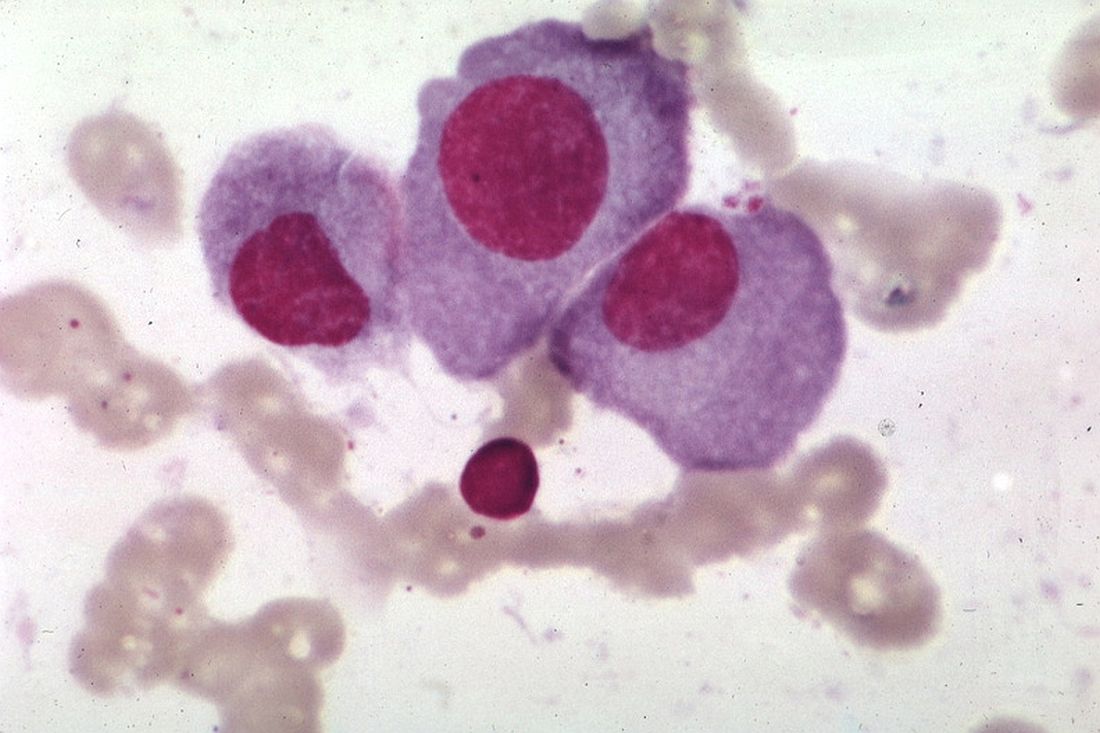

Researchers say they may have determined why African Americans have a two- to threefold increased risk of multiple myeloma (MM), compared with European Americans.

The team genotyped 881 MM samples from various racial groups and identified three gene subtypes – t(11;14), t(14;16), and t(14;20) – that explain the racial disparity.

They found that patients with African ancestry of 80% or more had a significantly higher occurrence of these subtypes, compared with individuals with African ancestry of less than 0.1%.

And these subtypes are driving the disparity in MM diagnoses between the populations.

Previous attempts to explain the disparity relied on self-reported race rather than quantitatively measured genetic ancestry, which could result in bias, Vincent Rajkumar, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and his colleagues reported in Blood Cancer Journal.

“A major new aspect of this study is that we identified the ancestry of each patient through DNA sequencing, which allowed us to determine ancestry more accurately,” Dr. Rajkumar said in a statement.

All 881 samples had abnormal plasma cell FISH, 851 had a normal chromosome study, and 30 had an abnormal study.

Median age for the entire group was 64 years. More samples were from men (54.3%) than women (45.7%). Researchers observed no significant difference between men and women in the proportion of primary cytogenetic abnormalities.

Of the 881 samples, the median African ancestry was 2.3%, the median European ancestry was 64.7%, and Northern European ancestry was 26.6%.

Thirty percent of the entire cohort had less than 0.1% African ancestry, and 13.6% had 80% or greater African ancestry.

Using a logistic regression model, the researchers determined that a 10% increase in the percentage of African ancestry was associated with a 6% increase in the odds of detecting t(11;14), t(14;16), or t(14;20) odds ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.11; P = .05).

The researchers plotted the probability of observing these cytogenetic abnormalities with the percentage of African ancestry and found the differences were most striking in the extreme populations – individuals with 80% or greater African ancestry and individuals with less than 0.1% African ancestry.

Upon further analysis, the team found a significantly higher prevalence of t(11;14), t(14;16), and t(14;20) in the group of patients with the greatest proportion of African ancestry (P = .008), compared with the European cohort.

The differences emerged in only the highest and lowest cohorts, they noted. Most patients (60%) were not included in these extreme populations because they had mixed ancestry.

The team observed no significant differences when the cutoff for African ancestry was greater than 50%.

The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute and the Mayo Clinic. One study author reported relationships with Celgene, Takeda, Prothena, Janssen, Pfizer, Alnylam, and GSK. Two authors reported relationships with the DNA Diagnostics Center.

SOURCE: Baughn LB et al. Blood Cancer J. 2018 Oct 10;8(10):96.

Researchers say they may have determined why African Americans have a two- to threefold increased risk of multiple myeloma (MM), compared with European Americans.

The team genotyped 881 MM samples from various racial groups and identified three gene subtypes – t(11;14), t(14;16), and t(14;20) – that explain the racial disparity.

They found that patients with African ancestry of 80% or more had a significantly higher occurrence of these subtypes, compared with individuals with African ancestry of less than 0.1%.

And these subtypes are driving the disparity in MM diagnoses between the populations.

Previous attempts to explain the disparity relied on self-reported race rather than quantitatively measured genetic ancestry, which could result in bias, Vincent Rajkumar, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and his colleagues reported in Blood Cancer Journal.

“A major new aspect of this study is that we identified the ancestry of each patient through DNA sequencing, which allowed us to determine ancestry more accurately,” Dr. Rajkumar said in a statement.

All 881 samples had abnormal plasma cell FISH, 851 had a normal chromosome study, and 30 had an abnormal study.

Median age for the entire group was 64 years. More samples were from men (54.3%) than women (45.7%). Researchers observed no significant difference between men and women in the proportion of primary cytogenetic abnormalities.

Of the 881 samples, the median African ancestry was 2.3%, the median European ancestry was 64.7%, and Northern European ancestry was 26.6%.

Thirty percent of the entire cohort had less than 0.1% African ancestry, and 13.6% had 80% or greater African ancestry.

Using a logistic regression model, the researchers determined that a 10% increase in the percentage of African ancestry was associated with a 6% increase in the odds of detecting t(11;14), t(14;16), or t(14;20) odds ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.11; P = .05).

The researchers plotted the probability of observing these cytogenetic abnormalities with the percentage of African ancestry and found the differences were most striking in the extreme populations – individuals with 80% or greater African ancestry and individuals with less than 0.1% African ancestry.

Upon further analysis, the team found a significantly higher prevalence of t(11;14), t(14;16), and t(14;20) in the group of patients with the greatest proportion of African ancestry (P = .008), compared with the European cohort.

The differences emerged in only the highest and lowest cohorts, they noted. Most patients (60%) were not included in these extreme populations because they had mixed ancestry.

The team observed no significant differences when the cutoff for African ancestry was greater than 50%.

The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute and the Mayo Clinic. One study author reported relationships with Celgene, Takeda, Prothena, Janssen, Pfizer, Alnylam, and GSK. Two authors reported relationships with the DNA Diagnostics Center.

SOURCE: Baughn LB et al. Blood Cancer J. 2018 Oct 10;8(10):96.

Researchers say they may have determined why African Americans have a two- to threefold increased risk of multiple myeloma (MM), compared with European Americans.

The team genotyped 881 MM samples from various racial groups and identified three gene subtypes – t(11;14), t(14;16), and t(14;20) – that explain the racial disparity.

They found that patients with African ancestry of 80% or more had a significantly higher occurrence of these subtypes, compared with individuals with African ancestry of less than 0.1%.

And these subtypes are driving the disparity in MM diagnoses between the populations.

Previous attempts to explain the disparity relied on self-reported race rather than quantitatively measured genetic ancestry, which could result in bias, Vincent Rajkumar, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and his colleagues reported in Blood Cancer Journal.

“A major new aspect of this study is that we identified the ancestry of each patient through DNA sequencing, which allowed us to determine ancestry more accurately,” Dr. Rajkumar said in a statement.

All 881 samples had abnormal plasma cell FISH, 851 had a normal chromosome study, and 30 had an abnormal study.

Median age for the entire group was 64 years. More samples were from men (54.3%) than women (45.7%). Researchers observed no significant difference between men and women in the proportion of primary cytogenetic abnormalities.

Of the 881 samples, the median African ancestry was 2.3%, the median European ancestry was 64.7%, and Northern European ancestry was 26.6%.

Thirty percent of the entire cohort had less than 0.1% African ancestry, and 13.6% had 80% or greater African ancestry.

Using a logistic regression model, the researchers determined that a 10% increase in the percentage of African ancestry was associated with a 6% increase in the odds of detecting t(11;14), t(14;16), or t(14;20) odds ratio, 1.06; 95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.11; P = .05).

The researchers plotted the probability of observing these cytogenetic abnormalities with the percentage of African ancestry and found the differences were most striking in the extreme populations – individuals with 80% or greater African ancestry and individuals with less than 0.1% African ancestry.

Upon further analysis, the team found a significantly higher prevalence of t(11;14), t(14;16), and t(14;20) in the group of patients with the greatest proportion of African ancestry (P = .008), compared with the European cohort.

The differences emerged in only the highest and lowest cohorts, they noted. Most patients (60%) were not included in these extreme populations because they had mixed ancestry.

The team observed no significant differences when the cutoff for African ancestry was greater than 50%.

The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute and the Mayo Clinic. One study author reported relationships with Celgene, Takeda, Prothena, Janssen, Pfizer, Alnylam, and GSK. Two authors reported relationships with the DNA Diagnostics Center.

SOURCE: Baughn LB et al. Blood Cancer J. 2018 Oct 10;8(10):96.

FROM BLOOD CANCER JOURNAL

Key clinical point:

Major finding: There was a significantly higher prevalence of t(11;14), t(14;16), and t(14:20) in patients with 80% or greater African ancestry, compared with the European cohort (P = .008).

Study details: The study included 881 samples from patients with an abnormal plasma cell proliferative disorder FISH result and concurrent conventional G-banded chromosome evaluation.

Disclosures: The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute and the Mayo Clinic. One study author reported relationships with Celgene, Takeda, Prothena, Janssen, Pfizer, Alnylam, and GSK. Two authors reported relationships with the DNA Diagnostics Center.

Source: Baughn LB et al. Blood Cancer J. 2018 Oct 10;8(10):96.