User login

CASE A lifelong habit

Ms. B, age 14, has diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder, and is taking extended-release (ER) methylphenidate, 36 mg/d. Her mother brings her to the hospital with concerns that Ms. B has been stealing small objects, such as money, toys, and pencils from home, school, and her peers, even though she does not need them and her family can afford to buy them for her. Ms. B’s mother routinely searches her daughter when she leaves the house and when she returns and frequently finds things in Ms. B’s possession that do not belong to her.

The mother reports that Ms. B’s stealing has been a lifelong habit that worsened after Ms. B’s father died in a car accident last year.

Ms. B does not volunteer any information about her stealing. She is admitted to a partial hospitalization program for further evaluation and treatment.

[polldaddy:9837962]

EVALUATION Continued stealing

A week later, Ms. B remains reluctant to talk about her stealing habit. However, once a therapeutic alliance is established, she reveals that she experiences increased anxiety before stealing and feels pleasure during the theft. Her methylphenidate ER dosage is increased to 54 mg/d in an attempt to address poor impulse control and subsequent stealing behavior. Her ADHD symptoms are controlled, and she does not exhibit poor impulse control in any situation other than stealing.

However, Ms. B continues to have poor insight and impaired judgment about her behavior. During treatment, Ms. B steals markers from the psychiatrist’s office, which later are found in her bag. When the staff convinces Ms. B to return the markers to the psychiatrist, she denies knowing how they got there. Behavioral interventions, including covert sensitization, systemic desensitization, positive reinforcement, body and bag search, and reminders, occur consistently as part of treatment, but have little effect on her symptoms.

The author’s observations

Risk-taking and novelty-seeking behaviors are common in adolescent patients. Impulsivity, instant reward-seeking behavior, and poor judgment can lead to stealing in this population, but this behavior is not necessarily indicative of kleptomania.

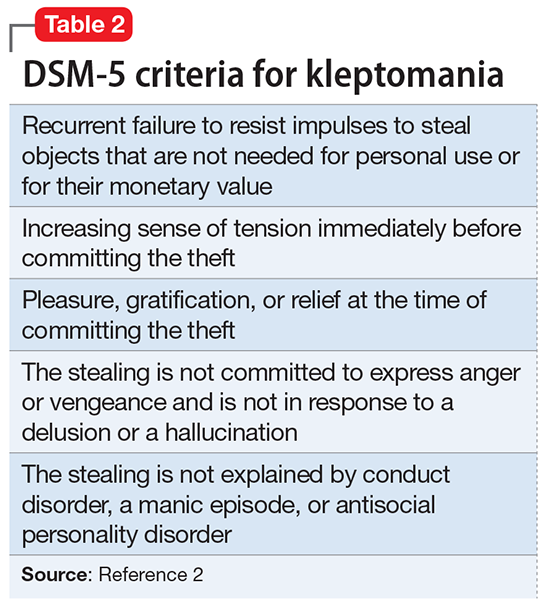

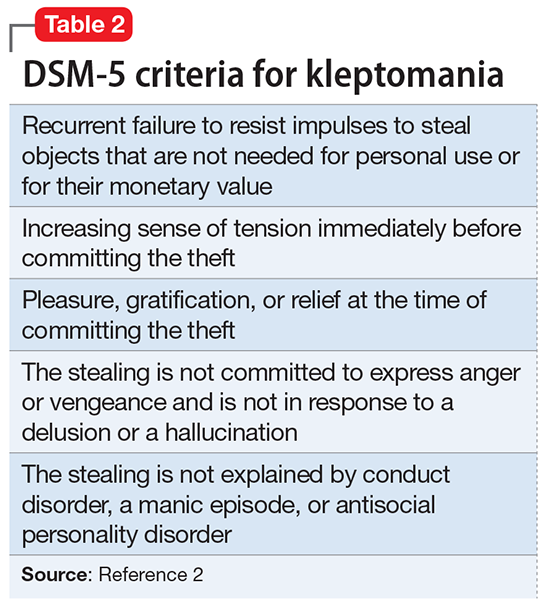

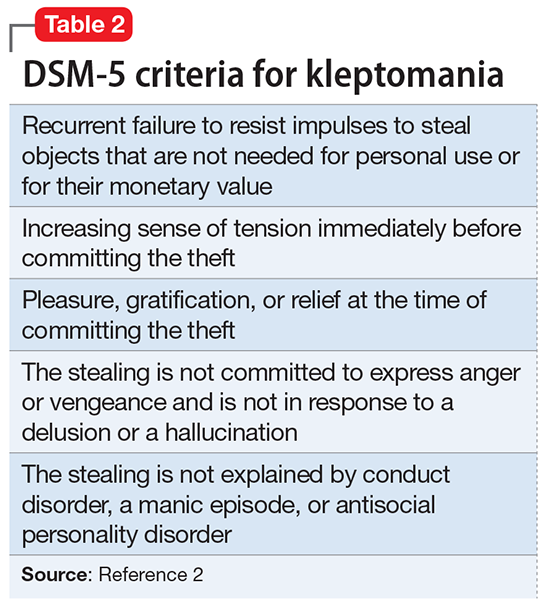

Kleptomania is the recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects.2 It differs from other forms of stealing in that the objects stolen by a patient with kleptomania are not needed for personal use or for their monetary value. Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence, is found in about 0.5% of the general population, and is more common among females.3

There are 2 important theories to explain kleptomania:

- The psychoanalytical theory explains kleptomania as an immature defense against unconscious impulses, conflicts, and desires of destruction. By stealing, the individual protects the self from narcissistic injury and disintegration. The frantic search for objects helps to divert self-destructive aggressiveness and allows for the preservation of the self.4

- The biological model indicates that individuals with kleptomania have a significant deficit of white matter in inferior frontal regions and poor integrity of the tracts connecting the limbic system to the thalamus and to the prefrontal cortex.5 Reward system circuitry (ventral tegmental area–nucleus accumbens–orbital frontal cortex) is likely to be involved in impulse control disorders including kleptomania.6

Comorbidity. Kleptomania often is comorbid with substance use disorder (SUD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and compulsive shopping, as well as depression, anxiety disorders, bulimia nervosa, and impulse control and conduct disorders.3,6

Kleptomania shares many characteristics with SUD, including continued engagement in a behavior despite negative consequences and the temporary reduction in urges after the behavior’s completion, followed by a return of the urge to steal. There also is a bidirectional relationship between OCD and kleptomania. Individuals with both disorders frequently engage in excessive and unnecessary rituals even when it is ego-dystonic. First-degree relatives of kleptomania patients have high rates of SUD and OCD.3

Serotonin, dopamine, and opioid pathways play a role in both kleptomania and other behavioral addictions.6 Clinicians should be cautious in treating comorbid disorders with stimulants. These agents may help patients with high impulsivity, but lead to disinhibition and worsen impulse control in patients with low impulsivity.7

TREATMENT Naltrexone

The psychiatrist discusses pharmacologic options to treat kleptomania with Ms. B and her mother. After considering the risks, benefits, adverse effects, and alternative treatments (including the option of no pharmacologic treatment), the mother consents and Ms. B assents to treatment with naltrexone, 25 mg/d. Before starting this medication, both the mother and Ms. B receive detailed psychoeducation describing naltrexone’s interactions with opioids. They are told that if Ms. B has a traumatic injury, they should inform the treatment team that she is taking naltrexone, which can acutely precipitate opiate withdrawal.

Before initiating pharmacotherapy, a comprehensive metabolic profile is obtained, and all values are within the normal range. After 1 week, naltrexone is increased to 50 mg/d. The medication is well tolerated, without any adverse effects.

[polldaddy:9837976]

The author’s observations

Behavioral interventions, such as covert sensitization and systemic desensitization, often are used to treat kleptomania.8 There are no FDA-approved medications for this condition. Opioid antagonists have been considered for the treatment of kleptomania.7

Mu-opioid receptors exist in highest concentrations in presynaptic neurons in the periaqueductal gray region and spinal cord and have high affinity for enkephalins and beta-endorphins. They also are involved in the reward and pleasure pathway. This neurocircuit is implicated in behavioral addiction.9

Naltrexone is an antagonist at μ-opioid receptors. It blocks the binding of endogenous and exogenous opioids at the receptors, particularly at the ventral tegmental area. By blocking the μ-receptor, naltrexone inhibits the processing of the reward and pleasure pathway involved in kleptomania. Naltrexone binds to these receptors, preventing the euphoric effects of behavioral addictions.10 This medication works best in conjunction with behavioral interventions.8

Naltrexone is a Schedule II drug. Use of naltrexone to treat kleptomania or other impulse control disorders is an off-label use of the medication. Naltrexone should not be prescribed to patients who are receiving opiates because it can cause acute opiate withdrawal.

Liver function tests should be monitored in all patients taking naltrexone. If liver function levels begin to rise, naltrexone should be discontinued. Naltrexone should be used with caution in patients with preexisting liver disease.11

OUTCOME Marked improvement

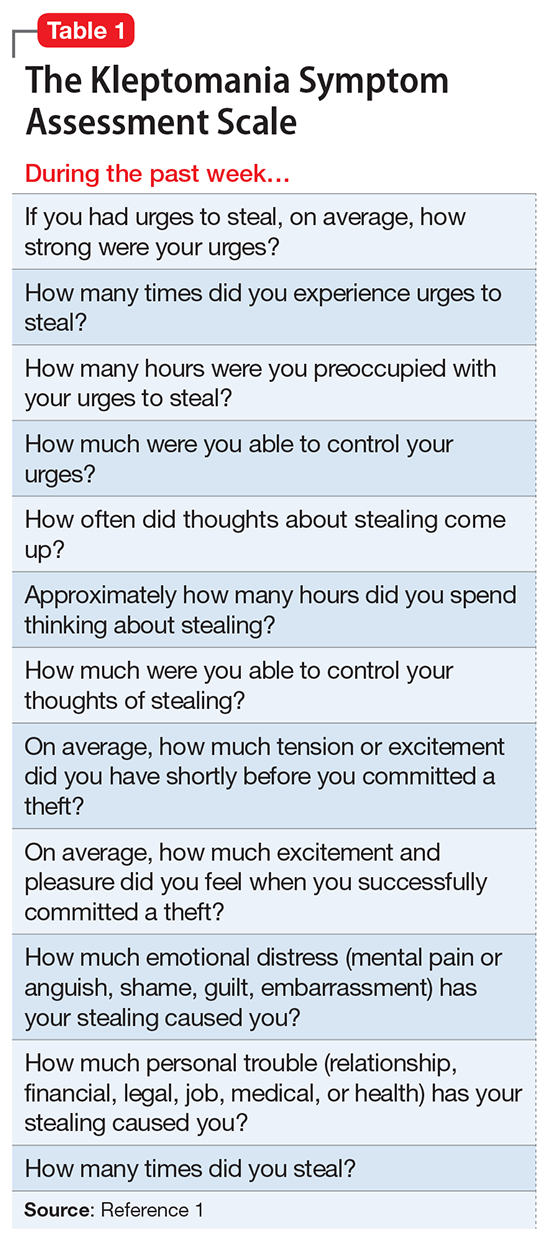

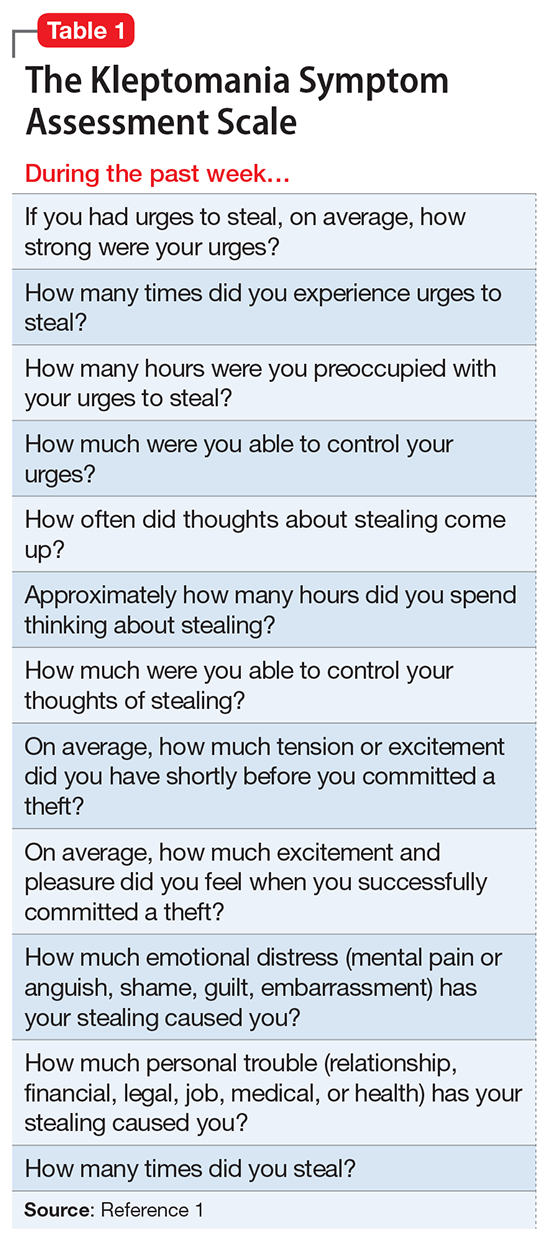

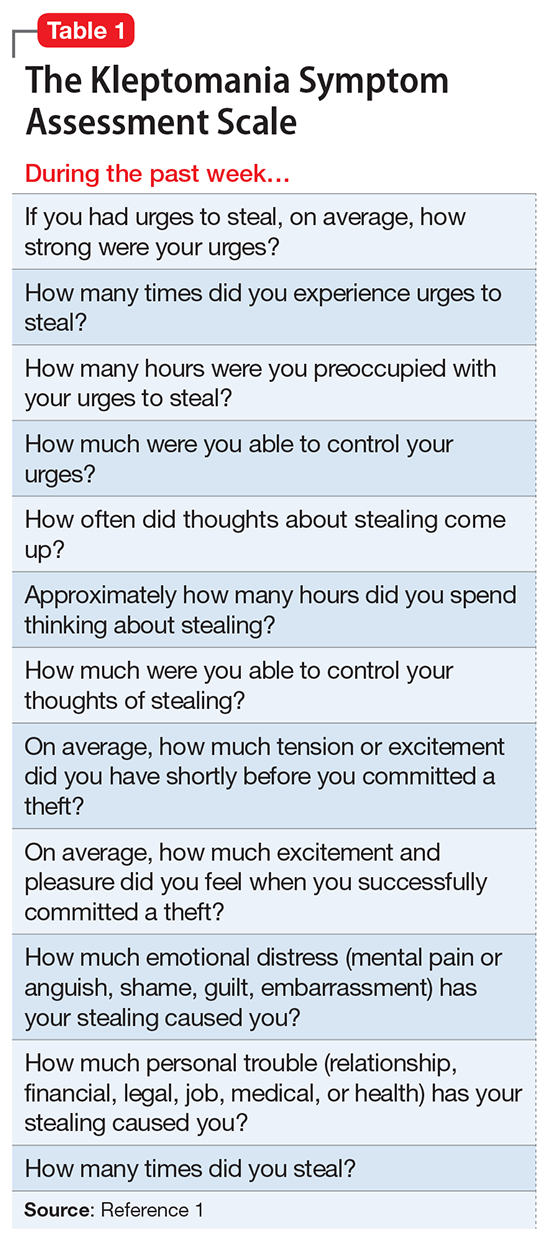

Ms. B’s K-SAS scores are evaluated 2 weeks after starting naltrexone. The results show a marked reduction in the urge to steal and in stealing behavior, and Ms. B’s mother reports no incidents of stealing in the previous week.

Ms. B is maintained on naltrexone, 50 mg/d, for 2 months. On repeated K-SAS scores, her mother rates Ms. B’s symptoms “very much improved” with “occasional” stealing. Ms. B is discharged from the intensive outpatient program.

1. Christianini AR, Conti MA, Hearst N, et al. Treating kleptomania: cross-cultural adaptation of the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale and assessment of an outpatient program. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:289-294.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Talih FR. Kleptomania and potential exacerbating factors: a review and case report. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):35-39.

4. Cierpka M. Psychodynamics of neurotically-induced kleptomania [in German]. Psychiatr Prax. 1986;13(3):94-103.

5. Grant JE, Correia S, Brennan-Krohn T. White matter integrity in kleptomania: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2006;147(2-3):233-237.

6. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

7. Zack M, Poulos CX. Effects of the atypical stimulant modafinil on a brief gambling episode in pathological gamblers with high vs. low impulsivity. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(6):660-671.

8. Grant JE. Understanding and treating kleptomania: new models and new treatments. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2006;43(2):81-87.

9. Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):142-151.

10. Grant JE, Kim SW. An open-label study of naltrexone in the treatment of kleptomania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):349-356.

11. Pfohl DN, Allen JI, Atkinson RL, et al. Naltrexone hydrochloride (Trexan): a review of serum transaminase elevations at high dosage. NIDA Res Monogr. 1986;67:66-72.

CASE A lifelong habit

Ms. B, age 14, has diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder, and is taking extended-release (ER) methylphenidate, 36 mg/d. Her mother brings her to the hospital with concerns that Ms. B has been stealing small objects, such as money, toys, and pencils from home, school, and her peers, even though she does not need them and her family can afford to buy them for her. Ms. B’s mother routinely searches her daughter when she leaves the house and when she returns and frequently finds things in Ms. B’s possession that do not belong to her.

The mother reports that Ms. B’s stealing has been a lifelong habit that worsened after Ms. B’s father died in a car accident last year.

Ms. B does not volunteer any information about her stealing. She is admitted to a partial hospitalization program for further evaluation and treatment.

[polldaddy:9837962]

EVALUATION Continued stealing

A week later, Ms. B remains reluctant to talk about her stealing habit. However, once a therapeutic alliance is established, she reveals that she experiences increased anxiety before stealing and feels pleasure during the theft. Her methylphenidate ER dosage is increased to 54 mg/d in an attempt to address poor impulse control and subsequent stealing behavior. Her ADHD symptoms are controlled, and she does not exhibit poor impulse control in any situation other than stealing.

However, Ms. B continues to have poor insight and impaired judgment about her behavior. During treatment, Ms. B steals markers from the psychiatrist’s office, which later are found in her bag. When the staff convinces Ms. B to return the markers to the psychiatrist, she denies knowing how they got there. Behavioral interventions, including covert sensitization, systemic desensitization, positive reinforcement, body and bag search, and reminders, occur consistently as part of treatment, but have little effect on her symptoms.

The author’s observations

Risk-taking and novelty-seeking behaviors are common in adolescent patients. Impulsivity, instant reward-seeking behavior, and poor judgment can lead to stealing in this population, but this behavior is not necessarily indicative of kleptomania.

Kleptomania is the recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects.2 It differs from other forms of stealing in that the objects stolen by a patient with kleptomania are not needed for personal use or for their monetary value. Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence, is found in about 0.5% of the general population, and is more common among females.3

There are 2 important theories to explain kleptomania:

- The psychoanalytical theory explains kleptomania as an immature defense against unconscious impulses, conflicts, and desires of destruction. By stealing, the individual protects the self from narcissistic injury and disintegration. The frantic search for objects helps to divert self-destructive aggressiveness and allows for the preservation of the self.4

- The biological model indicates that individuals with kleptomania have a significant deficit of white matter in inferior frontal regions and poor integrity of the tracts connecting the limbic system to the thalamus and to the prefrontal cortex.5 Reward system circuitry (ventral tegmental area–nucleus accumbens–orbital frontal cortex) is likely to be involved in impulse control disorders including kleptomania.6

Comorbidity. Kleptomania often is comorbid with substance use disorder (SUD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and compulsive shopping, as well as depression, anxiety disorders, bulimia nervosa, and impulse control and conduct disorders.3,6

Kleptomania shares many characteristics with SUD, including continued engagement in a behavior despite negative consequences and the temporary reduction in urges after the behavior’s completion, followed by a return of the urge to steal. There also is a bidirectional relationship between OCD and kleptomania. Individuals with both disorders frequently engage in excessive and unnecessary rituals even when it is ego-dystonic. First-degree relatives of kleptomania patients have high rates of SUD and OCD.3

Serotonin, dopamine, and opioid pathways play a role in both kleptomania and other behavioral addictions.6 Clinicians should be cautious in treating comorbid disorders with stimulants. These agents may help patients with high impulsivity, but lead to disinhibition and worsen impulse control in patients with low impulsivity.7

TREATMENT Naltrexone

The psychiatrist discusses pharmacologic options to treat kleptomania with Ms. B and her mother. After considering the risks, benefits, adverse effects, and alternative treatments (including the option of no pharmacologic treatment), the mother consents and Ms. B assents to treatment with naltrexone, 25 mg/d. Before starting this medication, both the mother and Ms. B receive detailed psychoeducation describing naltrexone’s interactions with opioids. They are told that if Ms. B has a traumatic injury, they should inform the treatment team that she is taking naltrexone, which can acutely precipitate opiate withdrawal.

Before initiating pharmacotherapy, a comprehensive metabolic profile is obtained, and all values are within the normal range. After 1 week, naltrexone is increased to 50 mg/d. The medication is well tolerated, without any adverse effects.

[polldaddy:9837976]

The author’s observations

Behavioral interventions, such as covert sensitization and systemic desensitization, often are used to treat kleptomania.8 There are no FDA-approved medications for this condition. Opioid antagonists have been considered for the treatment of kleptomania.7

Mu-opioid receptors exist in highest concentrations in presynaptic neurons in the periaqueductal gray region and spinal cord and have high affinity for enkephalins and beta-endorphins. They also are involved in the reward and pleasure pathway. This neurocircuit is implicated in behavioral addiction.9

Naltrexone is an antagonist at μ-opioid receptors. It blocks the binding of endogenous and exogenous opioids at the receptors, particularly at the ventral tegmental area. By blocking the μ-receptor, naltrexone inhibits the processing of the reward and pleasure pathway involved in kleptomania. Naltrexone binds to these receptors, preventing the euphoric effects of behavioral addictions.10 This medication works best in conjunction with behavioral interventions.8

Naltrexone is a Schedule II drug. Use of naltrexone to treat kleptomania or other impulse control disorders is an off-label use of the medication. Naltrexone should not be prescribed to patients who are receiving opiates because it can cause acute opiate withdrawal.

Liver function tests should be monitored in all patients taking naltrexone. If liver function levels begin to rise, naltrexone should be discontinued. Naltrexone should be used with caution in patients with preexisting liver disease.11

OUTCOME Marked improvement

Ms. B’s K-SAS scores are evaluated 2 weeks after starting naltrexone. The results show a marked reduction in the urge to steal and in stealing behavior, and Ms. B’s mother reports no incidents of stealing in the previous week.

Ms. B is maintained on naltrexone, 50 mg/d, for 2 months. On repeated K-SAS scores, her mother rates Ms. B’s symptoms “very much improved” with “occasional” stealing. Ms. B is discharged from the intensive outpatient program.

CASE A lifelong habit

Ms. B, age 14, has diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder, and is taking extended-release (ER) methylphenidate, 36 mg/d. Her mother brings her to the hospital with concerns that Ms. B has been stealing small objects, such as money, toys, and pencils from home, school, and her peers, even though she does not need them and her family can afford to buy them for her. Ms. B’s mother routinely searches her daughter when she leaves the house and when she returns and frequently finds things in Ms. B’s possession that do not belong to her.

The mother reports that Ms. B’s stealing has been a lifelong habit that worsened after Ms. B’s father died in a car accident last year.

Ms. B does not volunteer any information about her stealing. She is admitted to a partial hospitalization program for further evaluation and treatment.

[polldaddy:9837962]

EVALUATION Continued stealing

A week later, Ms. B remains reluctant to talk about her stealing habit. However, once a therapeutic alliance is established, she reveals that she experiences increased anxiety before stealing and feels pleasure during the theft. Her methylphenidate ER dosage is increased to 54 mg/d in an attempt to address poor impulse control and subsequent stealing behavior. Her ADHD symptoms are controlled, and she does not exhibit poor impulse control in any situation other than stealing.

However, Ms. B continues to have poor insight and impaired judgment about her behavior. During treatment, Ms. B steals markers from the psychiatrist’s office, which later are found in her bag. When the staff convinces Ms. B to return the markers to the psychiatrist, she denies knowing how they got there. Behavioral interventions, including covert sensitization, systemic desensitization, positive reinforcement, body and bag search, and reminders, occur consistently as part of treatment, but have little effect on her symptoms.

The author’s observations

Risk-taking and novelty-seeking behaviors are common in adolescent patients. Impulsivity, instant reward-seeking behavior, and poor judgment can lead to stealing in this population, but this behavior is not necessarily indicative of kleptomania.

Kleptomania is the recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects.2 It differs from other forms of stealing in that the objects stolen by a patient with kleptomania are not needed for personal use or for their monetary value. Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence, is found in about 0.5% of the general population, and is more common among females.3

There are 2 important theories to explain kleptomania:

- The psychoanalytical theory explains kleptomania as an immature defense against unconscious impulses, conflicts, and desires of destruction. By stealing, the individual protects the self from narcissistic injury and disintegration. The frantic search for objects helps to divert self-destructive aggressiveness and allows for the preservation of the self.4

- The biological model indicates that individuals with kleptomania have a significant deficit of white matter in inferior frontal regions and poor integrity of the tracts connecting the limbic system to the thalamus and to the prefrontal cortex.5 Reward system circuitry (ventral tegmental area–nucleus accumbens–orbital frontal cortex) is likely to be involved in impulse control disorders including kleptomania.6

Comorbidity. Kleptomania often is comorbid with substance use disorder (SUD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and compulsive shopping, as well as depression, anxiety disorders, bulimia nervosa, and impulse control and conduct disorders.3,6

Kleptomania shares many characteristics with SUD, including continued engagement in a behavior despite negative consequences and the temporary reduction in urges after the behavior’s completion, followed by a return of the urge to steal. There also is a bidirectional relationship between OCD and kleptomania. Individuals with both disorders frequently engage in excessive and unnecessary rituals even when it is ego-dystonic. First-degree relatives of kleptomania patients have high rates of SUD and OCD.3

Serotonin, dopamine, and opioid pathways play a role in both kleptomania and other behavioral addictions.6 Clinicians should be cautious in treating comorbid disorders with stimulants. These agents may help patients with high impulsivity, but lead to disinhibition and worsen impulse control in patients with low impulsivity.7

TREATMENT Naltrexone

The psychiatrist discusses pharmacologic options to treat kleptomania with Ms. B and her mother. After considering the risks, benefits, adverse effects, and alternative treatments (including the option of no pharmacologic treatment), the mother consents and Ms. B assents to treatment with naltrexone, 25 mg/d. Before starting this medication, both the mother and Ms. B receive detailed psychoeducation describing naltrexone’s interactions with opioids. They are told that if Ms. B has a traumatic injury, they should inform the treatment team that she is taking naltrexone, which can acutely precipitate opiate withdrawal.

Before initiating pharmacotherapy, a comprehensive metabolic profile is obtained, and all values are within the normal range. After 1 week, naltrexone is increased to 50 mg/d. The medication is well tolerated, without any adverse effects.

[polldaddy:9837976]

The author’s observations

Behavioral interventions, such as covert sensitization and systemic desensitization, often are used to treat kleptomania.8 There are no FDA-approved medications for this condition. Opioid antagonists have been considered for the treatment of kleptomania.7

Mu-opioid receptors exist in highest concentrations in presynaptic neurons in the periaqueductal gray region and spinal cord and have high affinity for enkephalins and beta-endorphins. They also are involved in the reward and pleasure pathway. This neurocircuit is implicated in behavioral addiction.9

Naltrexone is an antagonist at μ-opioid receptors. It blocks the binding of endogenous and exogenous opioids at the receptors, particularly at the ventral tegmental area. By blocking the μ-receptor, naltrexone inhibits the processing of the reward and pleasure pathway involved in kleptomania. Naltrexone binds to these receptors, preventing the euphoric effects of behavioral addictions.10 This medication works best in conjunction with behavioral interventions.8

Naltrexone is a Schedule II drug. Use of naltrexone to treat kleptomania or other impulse control disorders is an off-label use of the medication. Naltrexone should not be prescribed to patients who are receiving opiates because it can cause acute opiate withdrawal.

Liver function tests should be monitored in all patients taking naltrexone. If liver function levels begin to rise, naltrexone should be discontinued. Naltrexone should be used with caution in patients with preexisting liver disease.11

OUTCOME Marked improvement

Ms. B’s K-SAS scores are evaluated 2 weeks after starting naltrexone. The results show a marked reduction in the urge to steal and in stealing behavior, and Ms. B’s mother reports no incidents of stealing in the previous week.

Ms. B is maintained on naltrexone, 50 mg/d, for 2 months. On repeated K-SAS scores, her mother rates Ms. B’s symptoms “very much improved” with “occasional” stealing. Ms. B is discharged from the intensive outpatient program.

1. Christianini AR, Conti MA, Hearst N, et al. Treating kleptomania: cross-cultural adaptation of the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale and assessment of an outpatient program. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:289-294.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Talih FR. Kleptomania and potential exacerbating factors: a review and case report. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):35-39.

4. Cierpka M. Psychodynamics of neurotically-induced kleptomania [in German]. Psychiatr Prax. 1986;13(3):94-103.

5. Grant JE, Correia S, Brennan-Krohn T. White matter integrity in kleptomania: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2006;147(2-3):233-237.

6. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

7. Zack M, Poulos CX. Effects of the atypical stimulant modafinil on a brief gambling episode in pathological gamblers with high vs. low impulsivity. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(6):660-671.

8. Grant JE. Understanding and treating kleptomania: new models and new treatments. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2006;43(2):81-87.

9. Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):142-151.

10. Grant JE, Kim SW. An open-label study of naltrexone in the treatment of kleptomania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):349-356.

11. Pfohl DN, Allen JI, Atkinson RL, et al. Naltrexone hydrochloride (Trexan): a review of serum transaminase elevations at high dosage. NIDA Res Monogr. 1986;67:66-72.

1. Christianini AR, Conti MA, Hearst N, et al. Treating kleptomania: cross-cultural adaptation of the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale and assessment of an outpatient program. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:289-294.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Talih FR. Kleptomania and potential exacerbating factors: a review and case report. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):35-39.

4. Cierpka M. Psychodynamics of neurotically-induced kleptomania [in German]. Psychiatr Prax. 1986;13(3):94-103.

5. Grant JE, Correia S, Brennan-Krohn T. White matter integrity in kleptomania: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2006;147(2-3):233-237.

6. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

7. Zack M, Poulos CX. Effects of the atypical stimulant modafinil on a brief gambling episode in pathological gamblers with high vs. low impulsivity. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(6):660-671.

8. Grant JE. Understanding and treating kleptomania: new models and new treatments. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2006;43(2):81-87.

9. Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):142-151.

10. Grant JE, Kim SW. An open-label study of naltrexone in the treatment of kleptomania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):349-356.

11. Pfohl DN, Allen JI, Atkinson RL, et al. Naltrexone hydrochloride (Trexan): a review of serum transaminase elevations at high dosage. NIDA Res Monogr. 1986;67:66-72.