User login

CASE 1 Huge out-of-pocket cost makes patient forego treatment

Ms. M. is a 28-year-old patient who recently posted this on her Facebook page: “I went to the drugstore this morning to pick up a prescription, and as the pharmacist handed it to me she said, ‘That will be $180.00.’ And that’s after insurance coverage! Wow! I think I’ll pass!”

Our patients probably experience this type of situation more commonly than we know.

CASE 2 Catastrophic medical costs bankrupt family

A middle-class couple who had college degrees and full-time jobs with health insurance had twins at 24 weeks’ gestation. They accrued $450,000 in medical debt after exceeding the $2 million cap of their insurance policy. Having premature twins cost them everything. They liquidated their retirement and savings accounts, sold everything they had, and still ended up filing for bankruptcy.1

Costs indeed matter to patients, and we have a professional responsibility to help our patients navigate the murky waters of health care so that they can maintain financial as well as physical health.

Rising costs, lower yield,and opportunities for change

Rising health care costs are unsustainable for both our patients and our society. Although the United States spends more on health care than any other developed country, our health outcomes are actually worse—ranking at or near the bottom in both prevalence and mortality for multiple diseases, risk factors, and injuries.2

Of the 171 countries included in a study by the United Nations Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group, the United States was 1 of 13 countries that had an increasing maternal mortality and the only developed nation with an increasing maternal mortality rate.3 This tells us that, as our country spends more on health care, our patients’ health is not improving. For individuals, medical bills are now the leading cause of personal bankruptcy in the United States, even for those who are insured.4

ObGyns play an important leadership role in the practice of cost-conscious health care, as 25% of hospitalizations in the United States are pregnancy related.5,6 In addition, the wide scope of ObGyn practice reaches beyond pregnancy-related conditions and provides multiple opportunities to decrease the use of unnecessary tests and treatments.

The good news is that approximately 30% of health care costs are wasted on unnecessary care that could be eliminated without decreasing the quality of care.7

High-value change #1: Eliminate use of expensive products

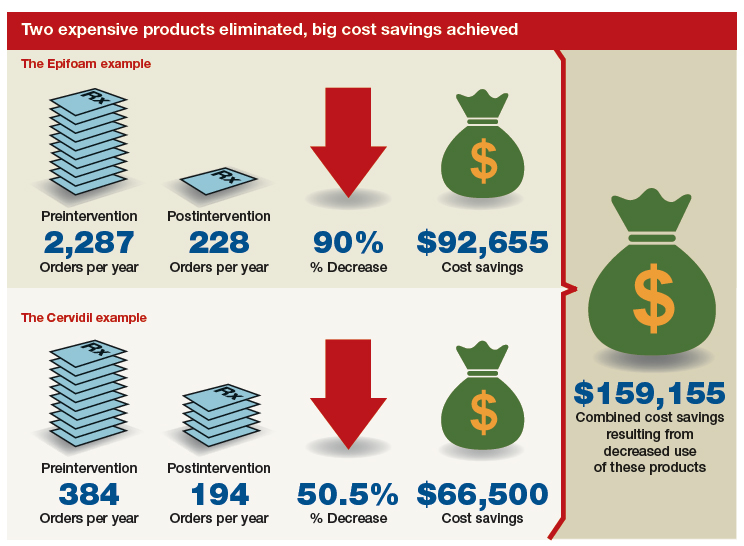

Embarking on a high-value care improvement project, experts at Greenville Health System examined the cost of different topical pain medications for perineal pain after a vaginal delivery. They found that Epifoam (hydrocortisone acetate/pramoxine hydrochloride) was ordered 2,287 times over the course of a year.

The study intervention consisted of an educational grand rounds and discussion of a Cochrane review, which concluded there was no difference in pain relief with topical anesthetics compared with placebo.8 Less expensive options for pain relief were discussed, and the department agreed to remove Epifoam as a standing order.

After the intervention, Epifoam was ordered 228 times, a 90% reduction. Over the period of a year, this translated to a cost savings of $92,655 for the hospital, with reduced charges passed on to patients.9 Thus, a seemingly small individual cost ($45.00 per can of Epifoam) can add up to a substantial sum in a large health care system.

Similarly, practitioners were educated about options for cervical ripening and were given information on the cost and efficacy of various cervical ripening agents. A Cochrane review found that oral misoprostol is as effective as vaginal misoprostol and results in fewer cesarean deliveries than vaginal dinoprostone (Cervidil).10 Practitioners were asked to consider making the transition to oral misoprostol. This action resulted in a 50.5% decrease in Cervidil use, from 384 to 194 cases, producing a cost savings of $66,500. The following year, the department removed Cervidil from the formulary as a high-value decision.9

Both of these examples illustrate what a value-minded department can accomplish by implementing performance improvement projects that focus on high-value care.

Continue to: High-value change #2: Stop ordering unnecessary lab work...

High-value change #2: Stop ordering unnecessary lab work

Another high-value change to consider: Examine each laboratory test order to understand if the test results will really alter the care of a patient. Providers vary, and ordering lab tests to “make sure” can add up as financial expense.

Best practices from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and other professional societies can help guide decision-making as we order lab tests. Think twice, for example, about whether every evaluation for preeclampsia requires a uric acid test, since ACOG does not endorse that as part of the diagnostic criteria. While a single uric acid test costs only $8.00 to $38.00 (according to Healthcare Bluebook), testing uric acid in many patients over the course of a year can add up to significant dollars.11

High-value change #3: Consider care redesign

In addition to seeking opportunities to use more cost-effective products and reduce the use of unnecessary tests, “care redesign” is an innovative way to provide high-quality care (and increased patient satisfaction) at a lower cost for both the health care system and the patient. A prime example of care redesign is using telehealth to enhance prenatal care.

Several health systems around the country are piloting and implementing remote blood pressure monitoring, app-based prenatal education, and telehealth visits to enhance prenatal care.12,13 Use of a home blood pressure monitor can reduce in-person visits for low-risk prenatal care and open up access for other patients. Additionally, allowing the patient to participate in her own care at home or work can eliminate drives to and waits in the office and reduce absence from work because of a doctor visit.

A systematic review of more than 60,000 women showed that low-risk women who attend 5 to 9 prenatal visits have the same outcomes as women who attend the standard schedule of 13 to 15 visits.14 Although patient satisfaction was higher with more visits, when a bidirectional app or a telehealth visit is offered as an option, then patient satisfaction is equivalent to that in the standard schedule group.12 So why not expand the choice for patients?

The challenge of teaching high-value care: Medical education responds

In a 2010 article in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Molly Cooke commented on medical education’s responsibility regarding cost consciousness in patient care, and she highlighted the importance of teaching medical students and residents about considering cost in treating patients.15 Similarly, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education asks residents to consider cost and stewardship of medical resources as one of its system-based practice competencies.16 In 2012, the Choosing Wisely campaign, initiated by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, asked specialty society members to identify tests or procedures commonly used in their field whose necessity should be questioned and discussed.17 ACOG and other women’s health specialty societies participate in this campaign.

From an educational standpoint, ACOG’s Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology has developed a curriculum resource, “Cases in High Value Care,” that can be used by any women’s health department to start the conversation on high-value care.18 The web program encourages medical students and residents to submit clinical vignettes that demonstrate examples of low- and high-value care. These cases can be used for discussion and debate and can serve as high-value care performance improvement projects in your own department.

Other useful publications are available outside the ObGyn specialty. Consider the Society of Hospital Medicine’s article series in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, “Choosing Wisely: Things We Do for No Reason”and “Choosing Wisely: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value.”19 The former focuses on discussing practices (tests, procedures, supplies, and prescriptions) that may be poorly supported by evidence or are part of standard practice even though other less expensive, higher-value alternatives may be available. The latter highlights perspective pieces that describe health care value initiatives relating to the practice of hospital medicine.

Continue to: The bottom line...

The bottom line

ObGyns and other health care providers are concerned about providing high-value care to patients and are working toward improving performance in this area. We really do care about the health care–related financial burdens that confront Ms. M., the premature twins’ parents, and all our patients.

- Sinconis J. Bankrupted by giving birth: having premature twins cost me everything. The Guardian. January 17, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/commentisfree/2018/jan/16/bankrupted-by-giving-birth-having-premature-twins-cost-me-everything. Accessed December 20, 2018.

- Woolf SH, Aron LY. The US health disadvantage relative to other high-income countries: findings from a National Research Council/Institute of Medicine report. JAMA. 2013;309:771-772.

- Ozimek JA, Kilpatrick SJ. Maternal mortality in the twenty-first century. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018;45:175-186.

- Himmelstein DU, Thorne D, Warren E, et al. Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: results of a national study. Am J Med. 2009;122:741-746.

- Healthy babies healthy business. March of Dimes website. http://www.marchofdimes.org/hbhb/index.asp. Accessed December 20, 2018.

- Werner EF. Cost matters. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:919-920.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine; Yong PL, Saunders RS, Olsen LA, eds. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

- Hedayati H, Parsons J, Crowther CA. Topically applied anaesthetics for treating perineal pain after childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD004223.

- Demosthenes LD, Lane AS, Blackhurst DW. Implementing high-value care. South Med J. 2015;108:645-648.

- Alfirevic Z, Aflaifel N, Weeks A. Oral misoprostol for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD001338.

- Lane A. Preeclampsia evaluation. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/CREOG/CREOG-Search/Cases-in-High-Value-Care/Example-2. Published July 14, 2015. Accessed July 10, 2018.

- Clark EN. Evidence-based prenatal care. University of Utah Health website. https://physicians.utah.edu/echo/pdfs/2018-06-29_evidence-based_prenatal_care.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2018.

- Marko KI, Krapf JM, Meltzer AC, et al. Testing the feasibility of remote patient monitoring in prenatal care using a mobile app and connected devices: a prospective observational trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5:e200.

- Dowswell T, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;10:CD000934.

- Cooke M. Cost consciousness in patient care—what is medical education’s responsibility? N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1253-1255.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common program requirements (residency).https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/Program Requirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2018.

- Choosing Wisely. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation website. http://www.choosingwisely.org/. Accessed August 7, 2018.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Cases in high value care. https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/CREOG/CREOG-Search/Cases-in-High-Value-Care. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Journal of Hospital Medicine website. https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/page/author-guidelines. Accessed August 8, 2018.

CASE 1 Huge out-of-pocket cost makes patient forego treatment

Ms. M. is a 28-year-old patient who recently posted this on her Facebook page: “I went to the drugstore this morning to pick up a prescription, and as the pharmacist handed it to me she said, ‘That will be $180.00.’ And that’s after insurance coverage! Wow! I think I’ll pass!”

Our patients probably experience this type of situation more commonly than we know.

CASE 2 Catastrophic medical costs bankrupt family

A middle-class couple who had college degrees and full-time jobs with health insurance had twins at 24 weeks’ gestation. They accrued $450,000 in medical debt after exceeding the $2 million cap of their insurance policy. Having premature twins cost them everything. They liquidated their retirement and savings accounts, sold everything they had, and still ended up filing for bankruptcy.1

Costs indeed matter to patients, and we have a professional responsibility to help our patients navigate the murky waters of health care so that they can maintain financial as well as physical health.

Rising costs, lower yield,and opportunities for change

Rising health care costs are unsustainable for both our patients and our society. Although the United States spends more on health care than any other developed country, our health outcomes are actually worse—ranking at or near the bottom in both prevalence and mortality for multiple diseases, risk factors, and injuries.2

Of the 171 countries included in a study by the United Nations Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group, the United States was 1 of 13 countries that had an increasing maternal mortality and the only developed nation with an increasing maternal mortality rate.3 This tells us that, as our country spends more on health care, our patients’ health is not improving. For individuals, medical bills are now the leading cause of personal bankruptcy in the United States, even for those who are insured.4

ObGyns play an important leadership role in the practice of cost-conscious health care, as 25% of hospitalizations in the United States are pregnancy related.5,6 In addition, the wide scope of ObGyn practice reaches beyond pregnancy-related conditions and provides multiple opportunities to decrease the use of unnecessary tests and treatments.

The good news is that approximately 30% of health care costs are wasted on unnecessary care that could be eliminated without decreasing the quality of care.7

High-value change #1: Eliminate use of expensive products

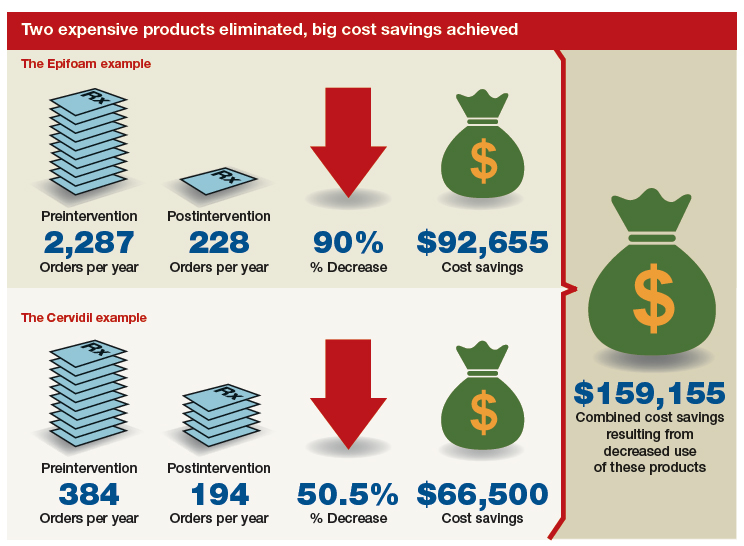

Embarking on a high-value care improvement project, experts at Greenville Health System examined the cost of different topical pain medications for perineal pain after a vaginal delivery. They found that Epifoam (hydrocortisone acetate/pramoxine hydrochloride) was ordered 2,287 times over the course of a year.

The study intervention consisted of an educational grand rounds and discussion of a Cochrane review, which concluded there was no difference in pain relief with topical anesthetics compared with placebo.8 Less expensive options for pain relief were discussed, and the department agreed to remove Epifoam as a standing order.

After the intervention, Epifoam was ordered 228 times, a 90% reduction. Over the period of a year, this translated to a cost savings of $92,655 for the hospital, with reduced charges passed on to patients.9 Thus, a seemingly small individual cost ($45.00 per can of Epifoam) can add up to a substantial sum in a large health care system.

Similarly, practitioners were educated about options for cervical ripening and were given information on the cost and efficacy of various cervical ripening agents. A Cochrane review found that oral misoprostol is as effective as vaginal misoprostol and results in fewer cesarean deliveries than vaginal dinoprostone (Cervidil).10 Practitioners were asked to consider making the transition to oral misoprostol. This action resulted in a 50.5% decrease in Cervidil use, from 384 to 194 cases, producing a cost savings of $66,500. The following year, the department removed Cervidil from the formulary as a high-value decision.9

Both of these examples illustrate what a value-minded department can accomplish by implementing performance improvement projects that focus on high-value care.

Continue to: High-value change #2: Stop ordering unnecessary lab work...

High-value change #2: Stop ordering unnecessary lab work

Another high-value change to consider: Examine each laboratory test order to understand if the test results will really alter the care of a patient. Providers vary, and ordering lab tests to “make sure” can add up as financial expense.

Best practices from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and other professional societies can help guide decision-making as we order lab tests. Think twice, for example, about whether every evaluation for preeclampsia requires a uric acid test, since ACOG does not endorse that as part of the diagnostic criteria. While a single uric acid test costs only $8.00 to $38.00 (according to Healthcare Bluebook), testing uric acid in many patients over the course of a year can add up to significant dollars.11

High-value change #3: Consider care redesign

In addition to seeking opportunities to use more cost-effective products and reduce the use of unnecessary tests, “care redesign” is an innovative way to provide high-quality care (and increased patient satisfaction) at a lower cost for both the health care system and the patient. A prime example of care redesign is using telehealth to enhance prenatal care.

Several health systems around the country are piloting and implementing remote blood pressure monitoring, app-based prenatal education, and telehealth visits to enhance prenatal care.12,13 Use of a home blood pressure monitor can reduce in-person visits for low-risk prenatal care and open up access for other patients. Additionally, allowing the patient to participate in her own care at home or work can eliminate drives to and waits in the office and reduce absence from work because of a doctor visit.

A systematic review of more than 60,000 women showed that low-risk women who attend 5 to 9 prenatal visits have the same outcomes as women who attend the standard schedule of 13 to 15 visits.14 Although patient satisfaction was higher with more visits, when a bidirectional app or a telehealth visit is offered as an option, then patient satisfaction is equivalent to that in the standard schedule group.12 So why not expand the choice for patients?

The challenge of teaching high-value care: Medical education responds

In a 2010 article in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Molly Cooke commented on medical education’s responsibility regarding cost consciousness in patient care, and she highlighted the importance of teaching medical students and residents about considering cost in treating patients.15 Similarly, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education asks residents to consider cost and stewardship of medical resources as one of its system-based practice competencies.16 In 2012, the Choosing Wisely campaign, initiated by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, asked specialty society members to identify tests or procedures commonly used in their field whose necessity should be questioned and discussed.17 ACOG and other women’s health specialty societies participate in this campaign.

From an educational standpoint, ACOG’s Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology has developed a curriculum resource, “Cases in High Value Care,” that can be used by any women’s health department to start the conversation on high-value care.18 The web program encourages medical students and residents to submit clinical vignettes that demonstrate examples of low- and high-value care. These cases can be used for discussion and debate and can serve as high-value care performance improvement projects in your own department.

Other useful publications are available outside the ObGyn specialty. Consider the Society of Hospital Medicine’s article series in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, “Choosing Wisely: Things We Do for No Reason”and “Choosing Wisely: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value.”19 The former focuses on discussing practices (tests, procedures, supplies, and prescriptions) that may be poorly supported by evidence or are part of standard practice even though other less expensive, higher-value alternatives may be available. The latter highlights perspective pieces that describe health care value initiatives relating to the practice of hospital medicine.

Continue to: The bottom line...

The bottom line

ObGyns and other health care providers are concerned about providing high-value care to patients and are working toward improving performance in this area. We really do care about the health care–related financial burdens that confront Ms. M., the premature twins’ parents, and all our patients.

CASE 1 Huge out-of-pocket cost makes patient forego treatment

Ms. M. is a 28-year-old patient who recently posted this on her Facebook page: “I went to the drugstore this morning to pick up a prescription, and as the pharmacist handed it to me she said, ‘That will be $180.00.’ And that’s after insurance coverage! Wow! I think I’ll pass!”

Our patients probably experience this type of situation more commonly than we know.

CASE 2 Catastrophic medical costs bankrupt family

A middle-class couple who had college degrees and full-time jobs with health insurance had twins at 24 weeks’ gestation. They accrued $450,000 in medical debt after exceeding the $2 million cap of their insurance policy. Having premature twins cost them everything. They liquidated their retirement and savings accounts, sold everything they had, and still ended up filing for bankruptcy.1

Costs indeed matter to patients, and we have a professional responsibility to help our patients navigate the murky waters of health care so that they can maintain financial as well as physical health.

Rising costs, lower yield,and opportunities for change

Rising health care costs are unsustainable for both our patients and our society. Although the United States spends more on health care than any other developed country, our health outcomes are actually worse—ranking at or near the bottom in both prevalence and mortality for multiple diseases, risk factors, and injuries.2

Of the 171 countries included in a study by the United Nations Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group, the United States was 1 of 13 countries that had an increasing maternal mortality and the only developed nation with an increasing maternal mortality rate.3 This tells us that, as our country spends more on health care, our patients’ health is not improving. For individuals, medical bills are now the leading cause of personal bankruptcy in the United States, even for those who are insured.4

ObGyns play an important leadership role in the practice of cost-conscious health care, as 25% of hospitalizations in the United States are pregnancy related.5,6 In addition, the wide scope of ObGyn practice reaches beyond pregnancy-related conditions and provides multiple opportunities to decrease the use of unnecessary tests and treatments.

The good news is that approximately 30% of health care costs are wasted on unnecessary care that could be eliminated without decreasing the quality of care.7

High-value change #1: Eliminate use of expensive products

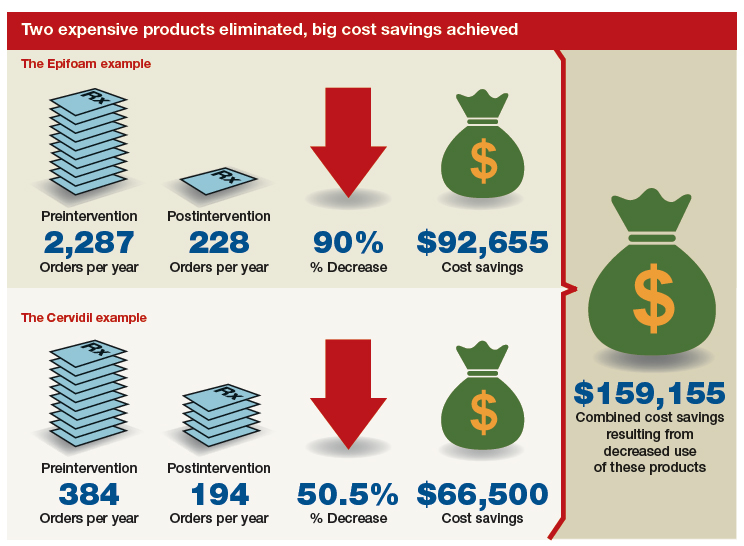

Embarking on a high-value care improvement project, experts at Greenville Health System examined the cost of different topical pain medications for perineal pain after a vaginal delivery. They found that Epifoam (hydrocortisone acetate/pramoxine hydrochloride) was ordered 2,287 times over the course of a year.

The study intervention consisted of an educational grand rounds and discussion of a Cochrane review, which concluded there was no difference in pain relief with topical anesthetics compared with placebo.8 Less expensive options for pain relief were discussed, and the department agreed to remove Epifoam as a standing order.

After the intervention, Epifoam was ordered 228 times, a 90% reduction. Over the period of a year, this translated to a cost savings of $92,655 for the hospital, with reduced charges passed on to patients.9 Thus, a seemingly small individual cost ($45.00 per can of Epifoam) can add up to a substantial sum in a large health care system.

Similarly, practitioners were educated about options for cervical ripening and were given information on the cost and efficacy of various cervical ripening agents. A Cochrane review found that oral misoprostol is as effective as vaginal misoprostol and results in fewer cesarean deliveries than vaginal dinoprostone (Cervidil).10 Practitioners were asked to consider making the transition to oral misoprostol. This action resulted in a 50.5% decrease in Cervidil use, from 384 to 194 cases, producing a cost savings of $66,500. The following year, the department removed Cervidil from the formulary as a high-value decision.9

Both of these examples illustrate what a value-minded department can accomplish by implementing performance improvement projects that focus on high-value care.

Continue to: High-value change #2: Stop ordering unnecessary lab work...

High-value change #2: Stop ordering unnecessary lab work

Another high-value change to consider: Examine each laboratory test order to understand if the test results will really alter the care of a patient. Providers vary, and ordering lab tests to “make sure” can add up as financial expense.

Best practices from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and other professional societies can help guide decision-making as we order lab tests. Think twice, for example, about whether every evaluation for preeclampsia requires a uric acid test, since ACOG does not endorse that as part of the diagnostic criteria. While a single uric acid test costs only $8.00 to $38.00 (according to Healthcare Bluebook), testing uric acid in many patients over the course of a year can add up to significant dollars.11

High-value change #3: Consider care redesign

In addition to seeking opportunities to use more cost-effective products and reduce the use of unnecessary tests, “care redesign” is an innovative way to provide high-quality care (and increased patient satisfaction) at a lower cost for both the health care system and the patient. A prime example of care redesign is using telehealth to enhance prenatal care.

Several health systems around the country are piloting and implementing remote blood pressure monitoring, app-based prenatal education, and telehealth visits to enhance prenatal care.12,13 Use of a home blood pressure monitor can reduce in-person visits for low-risk prenatal care and open up access for other patients. Additionally, allowing the patient to participate in her own care at home or work can eliminate drives to and waits in the office and reduce absence from work because of a doctor visit.

A systematic review of more than 60,000 women showed that low-risk women who attend 5 to 9 prenatal visits have the same outcomes as women who attend the standard schedule of 13 to 15 visits.14 Although patient satisfaction was higher with more visits, when a bidirectional app or a telehealth visit is offered as an option, then patient satisfaction is equivalent to that in the standard schedule group.12 So why not expand the choice for patients?

The challenge of teaching high-value care: Medical education responds

In a 2010 article in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Molly Cooke commented on medical education’s responsibility regarding cost consciousness in patient care, and she highlighted the importance of teaching medical students and residents about considering cost in treating patients.15 Similarly, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education asks residents to consider cost and stewardship of medical resources as one of its system-based practice competencies.16 In 2012, the Choosing Wisely campaign, initiated by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation, asked specialty society members to identify tests or procedures commonly used in their field whose necessity should be questioned and discussed.17 ACOG and other women’s health specialty societies participate in this campaign.

From an educational standpoint, ACOG’s Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology has developed a curriculum resource, “Cases in High Value Care,” that can be used by any women’s health department to start the conversation on high-value care.18 The web program encourages medical students and residents to submit clinical vignettes that demonstrate examples of low- and high-value care. These cases can be used for discussion and debate and can serve as high-value care performance improvement projects in your own department.

Other useful publications are available outside the ObGyn specialty. Consider the Society of Hospital Medicine’s article series in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, “Choosing Wisely: Things We Do for No Reason”and “Choosing Wisely: Next Steps in Improving Healthcare Value.”19 The former focuses on discussing practices (tests, procedures, supplies, and prescriptions) that may be poorly supported by evidence or are part of standard practice even though other less expensive, higher-value alternatives may be available. The latter highlights perspective pieces that describe health care value initiatives relating to the practice of hospital medicine.

Continue to: The bottom line...

The bottom line

ObGyns and other health care providers are concerned about providing high-value care to patients and are working toward improving performance in this area. We really do care about the health care–related financial burdens that confront Ms. M., the premature twins’ parents, and all our patients.

- Sinconis J. Bankrupted by giving birth: having premature twins cost me everything. The Guardian. January 17, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/commentisfree/2018/jan/16/bankrupted-by-giving-birth-having-premature-twins-cost-me-everything. Accessed December 20, 2018.

- Woolf SH, Aron LY. The US health disadvantage relative to other high-income countries: findings from a National Research Council/Institute of Medicine report. JAMA. 2013;309:771-772.

- Ozimek JA, Kilpatrick SJ. Maternal mortality in the twenty-first century. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018;45:175-186.

- Himmelstein DU, Thorne D, Warren E, et al. Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: results of a national study. Am J Med. 2009;122:741-746.

- Healthy babies healthy business. March of Dimes website. http://www.marchofdimes.org/hbhb/index.asp. Accessed December 20, 2018.

- Werner EF. Cost matters. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:919-920.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine; Yong PL, Saunders RS, Olsen LA, eds. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

- Hedayati H, Parsons J, Crowther CA. Topically applied anaesthetics for treating perineal pain after childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD004223.

- Demosthenes LD, Lane AS, Blackhurst DW. Implementing high-value care. South Med J. 2015;108:645-648.

- Alfirevic Z, Aflaifel N, Weeks A. Oral misoprostol for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD001338.

- Lane A. Preeclampsia evaluation. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/CREOG/CREOG-Search/Cases-in-High-Value-Care/Example-2. Published July 14, 2015. Accessed July 10, 2018.

- Clark EN. Evidence-based prenatal care. University of Utah Health website. https://physicians.utah.edu/echo/pdfs/2018-06-29_evidence-based_prenatal_care.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2018.

- Marko KI, Krapf JM, Meltzer AC, et al. Testing the feasibility of remote patient monitoring in prenatal care using a mobile app and connected devices: a prospective observational trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5:e200.

- Dowswell T, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;10:CD000934.

- Cooke M. Cost consciousness in patient care—what is medical education’s responsibility? N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1253-1255.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common program requirements (residency).https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/Program Requirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2018.

- Choosing Wisely. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation website. http://www.choosingwisely.org/. Accessed August 7, 2018.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Cases in high value care. https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/CREOG/CREOG-Search/Cases-in-High-Value-Care. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Journal of Hospital Medicine website. https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/page/author-guidelines. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Sinconis J. Bankrupted by giving birth: having premature twins cost me everything. The Guardian. January 17, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/commentisfree/2018/jan/16/bankrupted-by-giving-birth-having-premature-twins-cost-me-everything. Accessed December 20, 2018.

- Woolf SH, Aron LY. The US health disadvantage relative to other high-income countries: findings from a National Research Council/Institute of Medicine report. JAMA. 2013;309:771-772.

- Ozimek JA, Kilpatrick SJ. Maternal mortality in the twenty-first century. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2018;45:175-186.

- Himmelstein DU, Thorne D, Warren E, et al. Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: results of a national study. Am J Med. 2009;122:741-746.

- Healthy babies healthy business. March of Dimes website. http://www.marchofdimes.org/hbhb/index.asp. Accessed December 20, 2018.

- Werner EF. Cost matters. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:919-920.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine; Yong PL, Saunders RS, Olsen LA, eds. The Healthcare Imperative: Lowering Costs and Improving Outcomes: Workshop Series Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010.

- Hedayati H, Parsons J, Crowther CA. Topically applied anaesthetics for treating perineal pain after childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2:CD004223.

- Demosthenes LD, Lane AS, Blackhurst DW. Implementing high-value care. South Med J. 2015;108:645-648.

- Alfirevic Z, Aflaifel N, Weeks A. Oral misoprostol for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD001338.

- Lane A. Preeclampsia evaluation. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists website. https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/CREOG/CREOG-Search/Cases-in-High-Value-Care/Example-2. Published July 14, 2015. Accessed July 10, 2018.

- Clark EN. Evidence-based prenatal care. University of Utah Health website. https://physicians.utah.edu/echo/pdfs/2018-06-29_evidence-based_prenatal_care.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2018.

- Marko KI, Krapf JM, Meltzer AC, et al. Testing the feasibility of remote patient monitoring in prenatal care using a mobile app and connected devices: a prospective observational trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5:e200.

- Dowswell T, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;10:CD000934.

- Cooke M. Cost consciousness in patient care—what is medical education’s responsibility? N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1253-1255.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common program requirements (residency).https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/Program Requirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed December 19, 2018.

- Choosing Wisely. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation website. http://www.choosingwisely.org/. Accessed August 7, 2018.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Council on Resident Education in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Cases in high value care. https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/CREOG/CREOG-Search/Cases-in-High-Value-Care. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Journal of Hospital Medicine website. https://www.journalofhospitalmedicine.com/jhospmed/page/author-guidelines. Accessed August 8, 2018.