User login

Training in self-hypnosis, with or without biofeedback, is a valuable adjunct for children and adults with chronic illnesses or behavioral problems. After defining terms and briefly reviewing the evolution of medical hypnosis, this article provides an overview of the clinical utility and applications of self-hypnosis and various issues in its use, including patient assessment, concurrent use with biofeedback, and how health care providers can become trained in self-hypnosis instruction. Because my experience is primarily with medical hypnosis in children and adolescents, portions of this discussion will devote particular attention to the use of hypnosis in children.

DEFINITIONS

Hypnosis is a state of awareness, often but not always associated with relaxation, during which the participant can give him- or herself suggestions for desired changes to which he or she is more likely to respond than when in the usual state of awareness. Spontaneous self-hypnosis may happen while reading, listening to music, watching television, jogging, dancing, playing a musical instrument, doing tai chi, doing yoga, or performing similar activities. Terms often used to describe mind-body training include relaxation imagery, guided imagery, or visual imagery. These include the same training strategies as those used in hypnosis.

Biofeedback is a term coined in 1969 to describe procedures (developed in 1940s) for training subjects to alter physiologic responses such as brain activity, blood pressure, muscle tension, or heart rate. With biofeedback, participants are trained to improve their health and performance by using signals from their own bodies. In so doing, they strengthen awareness of the connections between their mind and body.

Cyberphysiology was defined by Dr. Earl E. Bakken at the first Archaeus Congress, held in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1986. “Cyber” derives from the Greek kybernan, meaning steersman or helmsman. From kybernan came the Latinate term govern, meaning “to control.” Thus, cyberphysiology means to control a physiologic response. In scientific terms, cyberphysiology is the study of how neurally mediated autonomic responses—usually viewed as automatic, reactive reflexes—can be modified by a learning process that appears to be significantly dependent on modification of mental images. Both hypnosis and biofeedback are cyberphysiologic strategies that enable the user to develop voluntary control of certain physiologic processes.

HISTORICAL BEGINNINGS OF HYPNOSIS

Franz Mesmer developed a training system that he called animal magnetism. Mesmer believed that normal body processes were disrupted when there was improper distribution of magnetism, a kind of fluid that could penetrate all matter. He described his ability to direct this magnetic fluid through his presence with the waving of a metallic rod and contact with a large wooden tub called a baquet. Mesmer was convinced that the successful therapeutic effects he observed depended on the magnetic rods he used.

When jealous and hostile colleagues challenged Mesmer’s clinical successes, King Louis XVI of France called for an investigative commission chaired by Benjamin Franklin, who was then the American ambassador to France. Other commission members included Dr. Antoine Lavoisier, the first to isolate the element of oxygen, and Dr. Antoine Guillotine, well known for developing a machine for beheading.1 After the commission conducted some clever experiments, they concluded that Mesmer’s success was related to application of the imagination. In fact, we are not far beyond that concept today, although we now have brain imaging documentation of changes in the brain associated with the practice of hypnosis.2–5

CORRECTING MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT HYPNOSIS

Hypnosis is not sleep

Modern hypnosis is considered to have begun with Mesmer, although the term hypnosis was first used by James Braid, a Scottish ophthalmologist, in 1843. His decision to derive the word from hypnos, the Greek word for sleep, was unfortunate. Hypnosis is not sleep, but the name confuses people.

All hypnosis is self-hypnosis

Another major misconception about hypnosis is that someone—ie, the hypnotist—is in control of a person. In fact, the hypnotist is a coach or teacher who helps the patient to increase his or her self-regulation abilities.6 All hypnosis is self-hypnosis; after the initial training, the learner must reinforce the training with daily practice. Adult learners should anticipate practicing approximately 10 minutes twice daily for about 2 months in order to condition the desirable physiologic change or outcome. Children learn more easily and often can achieve desired changes over a period of a few weeks.

IMPORTANCE OF PATIENT ASSESSMENT BEFORE TEACHING SELF-HYPNOSIS

Every candidate for self-hypnosis therapy deserves a thoughtful, careful diagnostic assessment that includes appropriate laboratory procedures, radiologic procedures, or both prior to decisions about treatment. Patients are sometimes referred for specific cyberphysiologic interventions, such as hypnosis, without adequate diagnostic assessments.7 When a patient is referred for hypnosis training, the health professional who will provide the training should evaluate the extent of the previous diagnostic assessment and do more if indicated. It is also important that the health professional be knowledgeable and competent with respect to the patient’s specific problem. For example, a dentist who is board-certified in dental hypnosis should not be teaching hypnosis to children with migraine, just as a pediatrician who is board-certified in medical hypnosis should not be extracting teeth using hypnosis.

Mental imagery varies from individual to individual. Many children have visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and olfactory/taste imagery abilities and can use these easily in the process of self-hypnosis. In contrast, many adults do not generate multiple types of mental imagery, and many lack clear visual imagery. It is important that the therapist identify which types of mental imagery the patient prefers before embarking on a therapeutic approach.

CONCURRENT USE OF BIOFEEDBACK AND HYPNOSIS

Much common ground exists between hypnosis and biofeedback. Both have the potential to provide a powerful validation of mind–body links, contribute to a lowered state of sympathetic arousal, heighten awareness of internal events and sensations, facilitate imagery abilities, narrow the focus of attention, and enhance the internal locus of control.

Adding biofeedback games to self-hypnosis training can make the experience much more interesting for children. Children see evidence on the screen that, by changing their thinking, they have control over a body response such as skin temperature, electrodermal activity, or pulse rate variability. Adults also benefit from the addition of biofeedback to self-hypnosis training. A patient cannot effect a change in a biofeedback response without a change in his or her mental imagery.

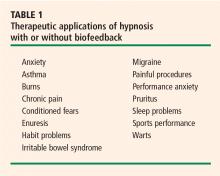

A WIDE RANGE OF THERAPEUTIC APPLICATIONS

Hypnosis training is valuable as a primary intervention for prevention of juvenile migraine8,9 as well as for many performance problems (eg, fear of public speaking or playing tennis), insomnia, and many habit problems (eg, nail-biting, tics, hair-pulling). For treatment of juvenile warts, hypnosis is at least as effective as topical treatment and associated with fewer relapses.10

Hypnosis is valuable as an adjunctive intervention during painful procedures,11–13 and many adults and children use self-hypnosis to teach themselves to be comfortable through procedures without any pharmacologic treatment.14

Training in self-hypnosis is a valuable adjunct for both children and adults with chronic illnesses such as cancer, cardiac failure, asthma, hemophilia, sickle cell disease, and arthritis. Self-hypnosis helps to reduce anxiety and increase comfort, and it provides a therapeutic tool over which the patient has control. Several recent studies have demonstrated the efficacy of hypnosis in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.15

Hypnosis and cardiac disease

With respect to cardiac disease, training in hypnosis can help to reduce symptoms both preoperatively and postoperatively, to enhance the success of rehabilitation following myocardial infarction, and to reduce anxiety associated with chronic heart disease.16

Hypnosis also is helpful for motivating behaviors associated with prevention of cardiac disease, such as regular exercise, eating a low-fat diet, and smoking cessation. Several studies have found hypnosis to be a helpful adjunct to cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of obesity.17 Additionally, a number of studies have demonstrated that hypnosis is useful as an initial intervention for smoking cessation,18 although only about 45% of persons who stop smoking with hypnosis continue to abstain 6 months later. In the case of both obesity and smoking cessation, hypnosis has modestly better efficacy compared with other treatments for these conditions.

TEACHING SELF-HYPNOSIS: SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS WITH CHILDREN

Self-hypnosis has great potential in children, as children delight in recognizing their own control over problems such as bed-wetting or wheezing or test anxiety.

As noted above, success with hypnosis requires that the patient practice self-hypnosis daily. In the case of children, it is essential that the coach or teacher emphasize that the child is in control and can decide when and where to use self-hypnosis. The message should be that self-hypnosis belongs to the child and that he or she needs to practice to become more skilled (as with learning soccer or some other sport), but that no one can force him or her to practice.

The choice of strategies for teaching self-hypnosis varies depending on the child’s age and developmental stage. As children mature, their cognitive abilities change. Preschool children are concrete in their thinking, so therapists working with children of this age must select words carefully. Children between ages 2 and 5 years spend a great deal of their time in various types of behavior based on imagination and fantasy. They enjoy stories and may enter a hypnotic state as a parent or teacher reads a story to them. Unlike adults, they often prefer to practice their self-hypnosis with their eyes open. Although adolescents may enjoy learning self-hypnosis methods that are similar to those preferred by adults, immature adolescents may prefer methods that also appeal to younger children. A child with cognitive impairment can learn self-hypnosis if the therapist selects a teaching approach appropriate for the child’s actual developmental stage. Because of developmental changes, a child of 9 years is unlikely to enjoy a method he or she was taught at age 4. Therapists who work with children should be familiar with a variety of hypnosis induction strategies and be capable of creative modification to accommodate a child’s changing developmental circumstances.19,20

HYPNOSIS RESEARCH WITH CHILDREN

Most subsequent research has consisted of clinical studies documenting the efficacy of hypnosis with children in areas such as pain management, habit problems, wart reduction, and performance anxiety. A recent study completed in Cleveland, Ohio, taught stress-reduction methods, including self-hypnosis, to 8-year-old schoolchildren.30 This study concluded that a short daily stress-management intervention delivered in the classroom setting in elementary school can decrease feelings of anxiety and improve a child’s ability to relax. Many of the children in the study continued to use self-hypnosis in their daily lives after the study was completed.

A host of variables complicate research design

The variability in preferences, learning styles, and developmental stages among children complicates the design of research protocols for studying hypnosis in children. These protocols are often written to describe identical hypnotic inductions, often tape-recorded, to be used at prescribed times. Measured variables do not include whether or not a child likes the induction, listens to the tape, or focuses on entirely different mental imagery of his or her own choosing. Learning disabilities, such as auditory processing handicaps, may interfere with children’s ability to learn and remember self-hypnosis training. Furthermore, learning disabilities are often subtle and may not be recognized without detailed testing.

Each of these variables complicates efforts to perform meta-analyses of hypnosis and related interventions. Analyses of studies on the efficacy of hypnosis in children should include all strategies that induce hypnosis in children—eg, visual imagery, guided imagery, and/or progressive relaxation. Some research studies that are defined as controlled nevertheless mix different therapeutic interventions. An example would be a comparison of hypnosis with guided imagery.

The International Society of Hypnosis is currently sponsoring Cochrane reviews of hypnotherapeutic interventions, including those with children.

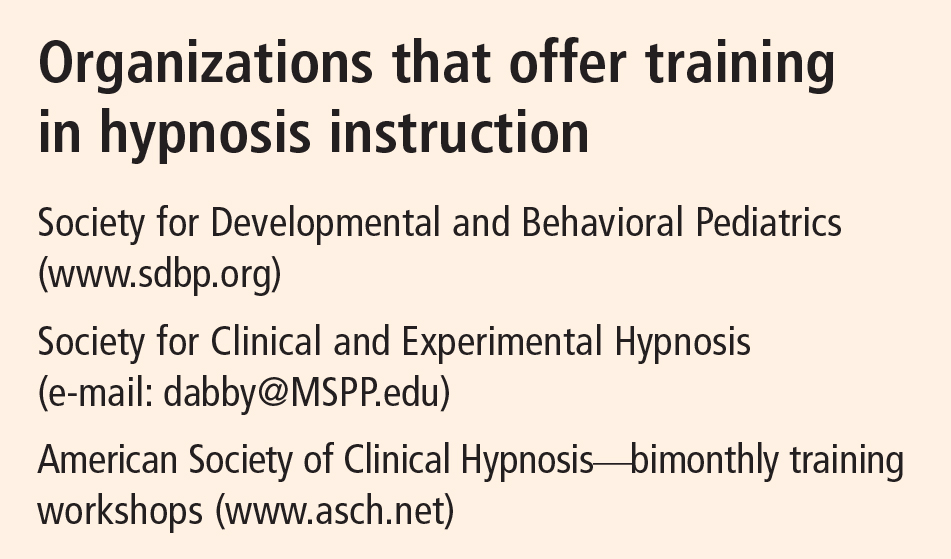

TRAINING IN HYPNOSIS INSTRUCTION

Health professionals who wish to teach self-hypnosis should take workshops sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Hypnosis or its component sections, or by the Society for Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. The Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics also provides annual workshops to prepare health professionals for teaching self-hypnosis to children. Contact information for these organizations is provided in the sidebar on this page.

The basic workshops should include at least 22 hours of supervised practice of hypnosis techniques and didactic information. After completing such basic training, the professional should seek a mentor who, by phone or e-mail, can provide guidance and support. The professional who is developing skills in self-hypnosis instruction should also attend follow-up workshops, watch videotapes of other teachers, and read basic textbooks and hypnosis journals recommended by professional hypnosis societies.

Hypnosis board examinations are given in four areas: medicine, dentistry, psychology, and social work. The American Society of Clinical Hypnosis has developed a hypnosis certification program for professionals who use hypnosis in their practice and teaching.

Importantly, the professional who is developing skills in self-hypnosis instruction should learn self-hypnosis for him- or herself. Learning self-hypnosis is a valuable lifelong skill that provides many benefits.

THE FUTURE

We anticipate that appropriate and early training in self-hypnosis and biofeedback can enable children to learn to control autonomic responses relating to cardiovascular function. Preventive work by pediatric health professionals may include monitoring of autonomic responses early in life, identification of children most at risk because of autonomic lability, and interventions to reduce that risk via hypnosis and biofeedback training. We anticipate that laboratory and brain imaging studies will provide increasing documentation of the impacts of hypnotic suggestions on neural processing, and that Cochrane reviews will demonstrate increasing evidence for the clinical value of hypnosis.

- Barabasz A, Watkins JG. The history of hypnosis and its relevance to present-day psychotherapy. In: Hypnotherapeutic Techniques. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge; 2005:1–26.

- Rainville P, Duncan GH, Price DD, Carrier B, Bushnell MC. Pain affect encoded in human anterior cingulate but not somatosensory cortex. Science 1997; 277:968–971.

- Rainville P, Carrier B, Hofbauer RK, Bushnell MC, Duncan GH. Dissociation of sensory and affective dimensions of pain using hypnotic modulation. Pain 1999; 82:159–171.

- Raz A, Kirsch I, Pollard J, Nitkin-Kaner Y. Suggestion reduces the Stroop effect. Psychol Sci 2006; 17:91–95.

- Oakley DA, Deely Q, Halligan PW. Hypnotic depth and response to suggestion under standardized conditions and fMRI scanning. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 2007; 55:32–58.

- Yapko MD. The myths about hypnosis and a dose of reality. In: Trancework: An Introduction to the Practice of Clinical Hypnosis. New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge; 2003:25–55.

- Olness K, Libbey P. Unrecognized biologic bases of behavioral symptoms in patients referred for hypnotherapy. Am J Clin Hypn 1987; 30:1–8.

- Olness K, MacDonald JT, Uden DL. Comparison of self-hypnosis and propranolol in the treatment of juvenile classic migraine. Pediatrics 1987; 79:593–597.

- Olness K, Hall H, Rozniecki JJ, Schmidt W, Theoharides TC. Mast cell activation in children with migraine before and after training in self-regulation. Headache 1999; 39:101–107.

- Felt B, Hall H, Olness K, et al. Wart regression in children: comparison of relaxation-imagery to topical treatment and equal time interventions. Am J Clin Hypn 1998; 41:130–137.

- Ewin D. The effect of hypnosis and mindset on burns. Psychiatr Ann 1986; 16:115–118.

- Kuttner L. No Fears, No Tears: Children with Cancer Coping with Pain [videotape]. Vancouver, BC: Canadian Cancer Society; 1986.

- Kuttner L. No Fears, No Tears: 13 Years Later [videotape]. Vancouver, BC: Canadian Cancer Society; 1999.

- Olness KN. Perspectives from physician-patients. In: Fredericks LE, ed. The Use of Hypnosis in Surgery and Anesthesia: Psychological Preparation of the Surgical Patient. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 2001:212–222.

- Palsson OS, Turner MJ, Johnson DA, Burnelt CK, Whitehead WE. Hypnosis treatment for severe irritable bowel syndrome: investigation of mechanism and effects on symptoms. Dig Dis Sci 2002; 47:2605–2614.

- Novoa R, Hammonds T. Clinical hypnosis for reduction of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Cleve Clin J Med 2008; 75(Suppl 2):S44–S47.

- Kirsch I. Hypnotic enhancement of cognitive-behavioral weight loss treatments.another meta-reanalysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996; 64:517–519.

- Green JP, Lynn SJ. Hypnosis and suggestion-based approaches to smoking cessation: an examination of the evidence. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 2000; 48:195–224.

- Olness K, Kohen DP. Hypnosis and Hypnotherapy with Children. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996.

- Wester WC II, Sugarman LI, eds. Therapeutic Hypnosis with Children and Adolescents. Bethel, CT: Crown House Publishing; 2007.

- London P, Cooper LM. Norms of hypnotic susceptibility in children. Dev Psychol 1969; 1:113–124.

- Morgan AH, Hilgard JR. The Stanford Hypnotic Clinical Scale for Children. Am J Clin Hypn 1978; 21:148–169.

- Dikel W, Olness K. Self-hypnosis, biofeedback, and voluntary peripheral temperature control in children. Pediatrics 1980; 66:335–340.

- Olness KN, Conroy MM. A pilot study of voluntary control of transcutaneous PO2 by children: a brief communication. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 1985; 33:1–5.

- Hogan M, MacDonald J, Olness K. Voluntary control of auditory evoked responses by children with and without hypnosis. Am J Clin Hypn 1984; 27:91–94.

- Olness K, Culbert T, Uden D. Self-regulation of salivary immunoglobulin A by children. Pediatrics 1989; 83:66–71.

- Hall HR, Minnes L, Tosi M, Olness K. Voluntary modulation of neutrophil adhesiveness using a cyberphysiologic strategy. Int J Neurosci 1992; 63:287–297.

- Hewson-Bower B. Psychological Treatment Decreases Colds and Flu in Children by Increasing Salivary Immunoglobin A [PhD thesis]. Perth, Western Australia: Murdoch University; 1995.

- Hewson-Bower B, Drummond PD. Secretory immunoglobulin A increases during relaxation in children with and without recurrent upper respiratory tract infections. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1996; 17: 311–316.

- Bothe DA, Olness KN. The effects of a stress management technique on elementary school children [abstract]. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2006; 27:429. Abstract 5.

Training in self-hypnosis, with or without biofeedback, is a valuable adjunct for children and adults with chronic illnesses or behavioral problems. After defining terms and briefly reviewing the evolution of medical hypnosis, this article provides an overview of the clinical utility and applications of self-hypnosis and various issues in its use, including patient assessment, concurrent use with biofeedback, and how health care providers can become trained in self-hypnosis instruction. Because my experience is primarily with medical hypnosis in children and adolescents, portions of this discussion will devote particular attention to the use of hypnosis in children.

DEFINITIONS

Hypnosis is a state of awareness, often but not always associated with relaxation, during which the participant can give him- or herself suggestions for desired changes to which he or she is more likely to respond than when in the usual state of awareness. Spontaneous self-hypnosis may happen while reading, listening to music, watching television, jogging, dancing, playing a musical instrument, doing tai chi, doing yoga, or performing similar activities. Terms often used to describe mind-body training include relaxation imagery, guided imagery, or visual imagery. These include the same training strategies as those used in hypnosis.

Biofeedback is a term coined in 1969 to describe procedures (developed in 1940s) for training subjects to alter physiologic responses such as brain activity, blood pressure, muscle tension, or heart rate. With biofeedback, participants are trained to improve their health and performance by using signals from their own bodies. In so doing, they strengthen awareness of the connections between their mind and body.

Cyberphysiology was defined by Dr. Earl E. Bakken at the first Archaeus Congress, held in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1986. “Cyber” derives from the Greek kybernan, meaning steersman or helmsman. From kybernan came the Latinate term govern, meaning “to control.” Thus, cyberphysiology means to control a physiologic response. In scientific terms, cyberphysiology is the study of how neurally mediated autonomic responses—usually viewed as automatic, reactive reflexes—can be modified by a learning process that appears to be significantly dependent on modification of mental images. Both hypnosis and biofeedback are cyberphysiologic strategies that enable the user to develop voluntary control of certain physiologic processes.

HISTORICAL BEGINNINGS OF HYPNOSIS

Franz Mesmer developed a training system that he called animal magnetism. Mesmer believed that normal body processes were disrupted when there was improper distribution of magnetism, a kind of fluid that could penetrate all matter. He described his ability to direct this magnetic fluid through his presence with the waving of a metallic rod and contact with a large wooden tub called a baquet. Mesmer was convinced that the successful therapeutic effects he observed depended on the magnetic rods he used.

When jealous and hostile colleagues challenged Mesmer’s clinical successes, King Louis XVI of France called for an investigative commission chaired by Benjamin Franklin, who was then the American ambassador to France. Other commission members included Dr. Antoine Lavoisier, the first to isolate the element of oxygen, and Dr. Antoine Guillotine, well known for developing a machine for beheading.1 After the commission conducted some clever experiments, they concluded that Mesmer’s success was related to application of the imagination. In fact, we are not far beyond that concept today, although we now have brain imaging documentation of changes in the brain associated with the practice of hypnosis.2–5

CORRECTING MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT HYPNOSIS

Hypnosis is not sleep

Modern hypnosis is considered to have begun with Mesmer, although the term hypnosis was first used by James Braid, a Scottish ophthalmologist, in 1843. His decision to derive the word from hypnos, the Greek word for sleep, was unfortunate. Hypnosis is not sleep, but the name confuses people.

All hypnosis is self-hypnosis

Another major misconception about hypnosis is that someone—ie, the hypnotist—is in control of a person. In fact, the hypnotist is a coach or teacher who helps the patient to increase his or her self-regulation abilities.6 All hypnosis is self-hypnosis; after the initial training, the learner must reinforce the training with daily practice. Adult learners should anticipate practicing approximately 10 minutes twice daily for about 2 months in order to condition the desirable physiologic change or outcome. Children learn more easily and often can achieve desired changes over a period of a few weeks.

IMPORTANCE OF PATIENT ASSESSMENT BEFORE TEACHING SELF-HYPNOSIS

Every candidate for self-hypnosis therapy deserves a thoughtful, careful diagnostic assessment that includes appropriate laboratory procedures, radiologic procedures, or both prior to decisions about treatment. Patients are sometimes referred for specific cyberphysiologic interventions, such as hypnosis, without adequate diagnostic assessments.7 When a patient is referred for hypnosis training, the health professional who will provide the training should evaluate the extent of the previous diagnostic assessment and do more if indicated. It is also important that the health professional be knowledgeable and competent with respect to the patient’s specific problem. For example, a dentist who is board-certified in dental hypnosis should not be teaching hypnosis to children with migraine, just as a pediatrician who is board-certified in medical hypnosis should not be extracting teeth using hypnosis.

Mental imagery varies from individual to individual. Many children have visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and olfactory/taste imagery abilities and can use these easily in the process of self-hypnosis. In contrast, many adults do not generate multiple types of mental imagery, and many lack clear visual imagery. It is important that the therapist identify which types of mental imagery the patient prefers before embarking on a therapeutic approach.

CONCURRENT USE OF BIOFEEDBACK AND HYPNOSIS

Much common ground exists between hypnosis and biofeedback. Both have the potential to provide a powerful validation of mind–body links, contribute to a lowered state of sympathetic arousal, heighten awareness of internal events and sensations, facilitate imagery abilities, narrow the focus of attention, and enhance the internal locus of control.

Adding biofeedback games to self-hypnosis training can make the experience much more interesting for children. Children see evidence on the screen that, by changing their thinking, they have control over a body response such as skin temperature, electrodermal activity, or pulse rate variability. Adults also benefit from the addition of biofeedback to self-hypnosis training. A patient cannot effect a change in a biofeedback response without a change in his or her mental imagery.

A WIDE RANGE OF THERAPEUTIC APPLICATIONS

Hypnosis training is valuable as a primary intervention for prevention of juvenile migraine8,9 as well as for many performance problems (eg, fear of public speaking or playing tennis), insomnia, and many habit problems (eg, nail-biting, tics, hair-pulling). For treatment of juvenile warts, hypnosis is at least as effective as topical treatment and associated with fewer relapses.10

Hypnosis is valuable as an adjunctive intervention during painful procedures,11–13 and many adults and children use self-hypnosis to teach themselves to be comfortable through procedures without any pharmacologic treatment.14

Training in self-hypnosis is a valuable adjunct for both children and adults with chronic illnesses such as cancer, cardiac failure, asthma, hemophilia, sickle cell disease, and arthritis. Self-hypnosis helps to reduce anxiety and increase comfort, and it provides a therapeutic tool over which the patient has control. Several recent studies have demonstrated the efficacy of hypnosis in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.15

Hypnosis and cardiac disease

With respect to cardiac disease, training in hypnosis can help to reduce symptoms both preoperatively and postoperatively, to enhance the success of rehabilitation following myocardial infarction, and to reduce anxiety associated with chronic heart disease.16

Hypnosis also is helpful for motivating behaviors associated with prevention of cardiac disease, such as regular exercise, eating a low-fat diet, and smoking cessation. Several studies have found hypnosis to be a helpful adjunct to cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of obesity.17 Additionally, a number of studies have demonstrated that hypnosis is useful as an initial intervention for smoking cessation,18 although only about 45% of persons who stop smoking with hypnosis continue to abstain 6 months later. In the case of both obesity and smoking cessation, hypnosis has modestly better efficacy compared with other treatments for these conditions.

TEACHING SELF-HYPNOSIS: SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS WITH CHILDREN

Self-hypnosis has great potential in children, as children delight in recognizing their own control over problems such as bed-wetting or wheezing or test anxiety.

As noted above, success with hypnosis requires that the patient practice self-hypnosis daily. In the case of children, it is essential that the coach or teacher emphasize that the child is in control and can decide when and where to use self-hypnosis. The message should be that self-hypnosis belongs to the child and that he or she needs to practice to become more skilled (as with learning soccer or some other sport), but that no one can force him or her to practice.

The choice of strategies for teaching self-hypnosis varies depending on the child’s age and developmental stage. As children mature, their cognitive abilities change. Preschool children are concrete in their thinking, so therapists working with children of this age must select words carefully. Children between ages 2 and 5 years spend a great deal of their time in various types of behavior based on imagination and fantasy. They enjoy stories and may enter a hypnotic state as a parent or teacher reads a story to them. Unlike adults, they often prefer to practice their self-hypnosis with their eyes open. Although adolescents may enjoy learning self-hypnosis methods that are similar to those preferred by adults, immature adolescents may prefer methods that also appeal to younger children. A child with cognitive impairment can learn self-hypnosis if the therapist selects a teaching approach appropriate for the child’s actual developmental stage. Because of developmental changes, a child of 9 years is unlikely to enjoy a method he or she was taught at age 4. Therapists who work with children should be familiar with a variety of hypnosis induction strategies and be capable of creative modification to accommodate a child’s changing developmental circumstances.19,20

HYPNOSIS RESEARCH WITH CHILDREN

Most subsequent research has consisted of clinical studies documenting the efficacy of hypnosis with children in areas such as pain management, habit problems, wart reduction, and performance anxiety. A recent study completed in Cleveland, Ohio, taught stress-reduction methods, including self-hypnosis, to 8-year-old schoolchildren.30 This study concluded that a short daily stress-management intervention delivered in the classroom setting in elementary school can decrease feelings of anxiety and improve a child’s ability to relax. Many of the children in the study continued to use self-hypnosis in their daily lives after the study was completed.

A host of variables complicate research design

The variability in preferences, learning styles, and developmental stages among children complicates the design of research protocols for studying hypnosis in children. These protocols are often written to describe identical hypnotic inductions, often tape-recorded, to be used at prescribed times. Measured variables do not include whether or not a child likes the induction, listens to the tape, or focuses on entirely different mental imagery of his or her own choosing. Learning disabilities, such as auditory processing handicaps, may interfere with children’s ability to learn and remember self-hypnosis training. Furthermore, learning disabilities are often subtle and may not be recognized without detailed testing.

Each of these variables complicates efforts to perform meta-analyses of hypnosis and related interventions. Analyses of studies on the efficacy of hypnosis in children should include all strategies that induce hypnosis in children—eg, visual imagery, guided imagery, and/or progressive relaxation. Some research studies that are defined as controlled nevertheless mix different therapeutic interventions. An example would be a comparison of hypnosis with guided imagery.

The International Society of Hypnosis is currently sponsoring Cochrane reviews of hypnotherapeutic interventions, including those with children.

TRAINING IN HYPNOSIS INSTRUCTION

Health professionals who wish to teach self-hypnosis should take workshops sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Hypnosis or its component sections, or by the Society for Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. The Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics also provides annual workshops to prepare health professionals for teaching self-hypnosis to children. Contact information for these organizations is provided in the sidebar on this page.

The basic workshops should include at least 22 hours of supervised practice of hypnosis techniques and didactic information. After completing such basic training, the professional should seek a mentor who, by phone or e-mail, can provide guidance and support. The professional who is developing skills in self-hypnosis instruction should also attend follow-up workshops, watch videotapes of other teachers, and read basic textbooks and hypnosis journals recommended by professional hypnosis societies.

Hypnosis board examinations are given in four areas: medicine, dentistry, psychology, and social work. The American Society of Clinical Hypnosis has developed a hypnosis certification program for professionals who use hypnosis in their practice and teaching.

Importantly, the professional who is developing skills in self-hypnosis instruction should learn self-hypnosis for him- or herself. Learning self-hypnosis is a valuable lifelong skill that provides many benefits.

THE FUTURE

We anticipate that appropriate and early training in self-hypnosis and biofeedback can enable children to learn to control autonomic responses relating to cardiovascular function. Preventive work by pediatric health professionals may include monitoring of autonomic responses early in life, identification of children most at risk because of autonomic lability, and interventions to reduce that risk via hypnosis and biofeedback training. We anticipate that laboratory and brain imaging studies will provide increasing documentation of the impacts of hypnotic suggestions on neural processing, and that Cochrane reviews will demonstrate increasing evidence for the clinical value of hypnosis.

Training in self-hypnosis, with or without biofeedback, is a valuable adjunct for children and adults with chronic illnesses or behavioral problems. After defining terms and briefly reviewing the evolution of medical hypnosis, this article provides an overview of the clinical utility and applications of self-hypnosis and various issues in its use, including patient assessment, concurrent use with biofeedback, and how health care providers can become trained in self-hypnosis instruction. Because my experience is primarily with medical hypnosis in children and adolescents, portions of this discussion will devote particular attention to the use of hypnosis in children.

DEFINITIONS

Hypnosis is a state of awareness, often but not always associated with relaxation, during which the participant can give him- or herself suggestions for desired changes to which he or she is more likely to respond than when in the usual state of awareness. Spontaneous self-hypnosis may happen while reading, listening to music, watching television, jogging, dancing, playing a musical instrument, doing tai chi, doing yoga, or performing similar activities. Terms often used to describe mind-body training include relaxation imagery, guided imagery, or visual imagery. These include the same training strategies as those used in hypnosis.

Biofeedback is a term coined in 1969 to describe procedures (developed in 1940s) for training subjects to alter physiologic responses such as brain activity, blood pressure, muscle tension, or heart rate. With biofeedback, participants are trained to improve their health and performance by using signals from their own bodies. In so doing, they strengthen awareness of the connections between their mind and body.

Cyberphysiology was defined by Dr. Earl E. Bakken at the first Archaeus Congress, held in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1986. “Cyber” derives from the Greek kybernan, meaning steersman or helmsman. From kybernan came the Latinate term govern, meaning “to control.” Thus, cyberphysiology means to control a physiologic response. In scientific terms, cyberphysiology is the study of how neurally mediated autonomic responses—usually viewed as automatic, reactive reflexes—can be modified by a learning process that appears to be significantly dependent on modification of mental images. Both hypnosis and biofeedback are cyberphysiologic strategies that enable the user to develop voluntary control of certain physiologic processes.

HISTORICAL BEGINNINGS OF HYPNOSIS

Franz Mesmer developed a training system that he called animal magnetism. Mesmer believed that normal body processes were disrupted when there was improper distribution of magnetism, a kind of fluid that could penetrate all matter. He described his ability to direct this magnetic fluid through his presence with the waving of a metallic rod and contact with a large wooden tub called a baquet. Mesmer was convinced that the successful therapeutic effects he observed depended on the magnetic rods he used.

When jealous and hostile colleagues challenged Mesmer’s clinical successes, King Louis XVI of France called for an investigative commission chaired by Benjamin Franklin, who was then the American ambassador to France. Other commission members included Dr. Antoine Lavoisier, the first to isolate the element of oxygen, and Dr. Antoine Guillotine, well known for developing a machine for beheading.1 After the commission conducted some clever experiments, they concluded that Mesmer’s success was related to application of the imagination. In fact, we are not far beyond that concept today, although we now have brain imaging documentation of changes in the brain associated with the practice of hypnosis.2–5

CORRECTING MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT HYPNOSIS

Hypnosis is not sleep

Modern hypnosis is considered to have begun with Mesmer, although the term hypnosis was first used by James Braid, a Scottish ophthalmologist, in 1843. His decision to derive the word from hypnos, the Greek word for sleep, was unfortunate. Hypnosis is not sleep, but the name confuses people.

All hypnosis is self-hypnosis

Another major misconception about hypnosis is that someone—ie, the hypnotist—is in control of a person. In fact, the hypnotist is a coach or teacher who helps the patient to increase his or her self-regulation abilities.6 All hypnosis is self-hypnosis; after the initial training, the learner must reinforce the training with daily practice. Adult learners should anticipate practicing approximately 10 minutes twice daily for about 2 months in order to condition the desirable physiologic change or outcome. Children learn more easily and often can achieve desired changes over a period of a few weeks.

IMPORTANCE OF PATIENT ASSESSMENT BEFORE TEACHING SELF-HYPNOSIS

Every candidate for self-hypnosis therapy deserves a thoughtful, careful diagnostic assessment that includes appropriate laboratory procedures, radiologic procedures, or both prior to decisions about treatment. Patients are sometimes referred for specific cyberphysiologic interventions, such as hypnosis, without adequate diagnostic assessments.7 When a patient is referred for hypnosis training, the health professional who will provide the training should evaluate the extent of the previous diagnostic assessment and do more if indicated. It is also important that the health professional be knowledgeable and competent with respect to the patient’s specific problem. For example, a dentist who is board-certified in dental hypnosis should not be teaching hypnosis to children with migraine, just as a pediatrician who is board-certified in medical hypnosis should not be extracting teeth using hypnosis.

Mental imagery varies from individual to individual. Many children have visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and olfactory/taste imagery abilities and can use these easily in the process of self-hypnosis. In contrast, many adults do not generate multiple types of mental imagery, and many lack clear visual imagery. It is important that the therapist identify which types of mental imagery the patient prefers before embarking on a therapeutic approach.

CONCURRENT USE OF BIOFEEDBACK AND HYPNOSIS

Much common ground exists between hypnosis and biofeedback. Both have the potential to provide a powerful validation of mind–body links, contribute to a lowered state of sympathetic arousal, heighten awareness of internal events and sensations, facilitate imagery abilities, narrow the focus of attention, and enhance the internal locus of control.

Adding biofeedback games to self-hypnosis training can make the experience much more interesting for children. Children see evidence on the screen that, by changing their thinking, they have control over a body response such as skin temperature, electrodermal activity, or pulse rate variability. Adults also benefit from the addition of biofeedback to self-hypnosis training. A patient cannot effect a change in a biofeedback response without a change in his or her mental imagery.

A WIDE RANGE OF THERAPEUTIC APPLICATIONS

Hypnosis training is valuable as a primary intervention for prevention of juvenile migraine8,9 as well as for many performance problems (eg, fear of public speaking or playing tennis), insomnia, and many habit problems (eg, nail-biting, tics, hair-pulling). For treatment of juvenile warts, hypnosis is at least as effective as topical treatment and associated with fewer relapses.10

Hypnosis is valuable as an adjunctive intervention during painful procedures,11–13 and many adults and children use self-hypnosis to teach themselves to be comfortable through procedures without any pharmacologic treatment.14

Training in self-hypnosis is a valuable adjunct for both children and adults with chronic illnesses such as cancer, cardiac failure, asthma, hemophilia, sickle cell disease, and arthritis. Self-hypnosis helps to reduce anxiety and increase comfort, and it provides a therapeutic tool over which the patient has control. Several recent studies have demonstrated the efficacy of hypnosis in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome.15

Hypnosis and cardiac disease

With respect to cardiac disease, training in hypnosis can help to reduce symptoms both preoperatively and postoperatively, to enhance the success of rehabilitation following myocardial infarction, and to reduce anxiety associated with chronic heart disease.16

Hypnosis also is helpful for motivating behaviors associated with prevention of cardiac disease, such as regular exercise, eating a low-fat diet, and smoking cessation. Several studies have found hypnosis to be a helpful adjunct to cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of obesity.17 Additionally, a number of studies have demonstrated that hypnosis is useful as an initial intervention for smoking cessation,18 although only about 45% of persons who stop smoking with hypnosis continue to abstain 6 months later. In the case of both obesity and smoking cessation, hypnosis has modestly better efficacy compared with other treatments for these conditions.

TEACHING SELF-HYPNOSIS: SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS WITH CHILDREN

Self-hypnosis has great potential in children, as children delight in recognizing their own control over problems such as bed-wetting or wheezing or test anxiety.

As noted above, success with hypnosis requires that the patient practice self-hypnosis daily. In the case of children, it is essential that the coach or teacher emphasize that the child is in control and can decide when and where to use self-hypnosis. The message should be that self-hypnosis belongs to the child and that he or she needs to practice to become more skilled (as with learning soccer or some other sport), but that no one can force him or her to practice.

The choice of strategies for teaching self-hypnosis varies depending on the child’s age and developmental stage. As children mature, their cognitive abilities change. Preschool children are concrete in their thinking, so therapists working with children of this age must select words carefully. Children between ages 2 and 5 years spend a great deal of their time in various types of behavior based on imagination and fantasy. They enjoy stories and may enter a hypnotic state as a parent or teacher reads a story to them. Unlike adults, they often prefer to practice their self-hypnosis with their eyes open. Although adolescents may enjoy learning self-hypnosis methods that are similar to those preferred by adults, immature adolescents may prefer methods that also appeal to younger children. A child with cognitive impairment can learn self-hypnosis if the therapist selects a teaching approach appropriate for the child’s actual developmental stage. Because of developmental changes, a child of 9 years is unlikely to enjoy a method he or she was taught at age 4. Therapists who work with children should be familiar with a variety of hypnosis induction strategies and be capable of creative modification to accommodate a child’s changing developmental circumstances.19,20

HYPNOSIS RESEARCH WITH CHILDREN

Most subsequent research has consisted of clinical studies documenting the efficacy of hypnosis with children in areas such as pain management, habit problems, wart reduction, and performance anxiety. A recent study completed in Cleveland, Ohio, taught stress-reduction methods, including self-hypnosis, to 8-year-old schoolchildren.30 This study concluded that a short daily stress-management intervention delivered in the classroom setting in elementary school can decrease feelings of anxiety and improve a child’s ability to relax. Many of the children in the study continued to use self-hypnosis in their daily lives after the study was completed.

A host of variables complicate research design

The variability in preferences, learning styles, and developmental stages among children complicates the design of research protocols for studying hypnosis in children. These protocols are often written to describe identical hypnotic inductions, often tape-recorded, to be used at prescribed times. Measured variables do not include whether or not a child likes the induction, listens to the tape, or focuses on entirely different mental imagery of his or her own choosing. Learning disabilities, such as auditory processing handicaps, may interfere with children’s ability to learn and remember self-hypnosis training. Furthermore, learning disabilities are often subtle and may not be recognized without detailed testing.

Each of these variables complicates efforts to perform meta-analyses of hypnosis and related interventions. Analyses of studies on the efficacy of hypnosis in children should include all strategies that induce hypnosis in children—eg, visual imagery, guided imagery, and/or progressive relaxation. Some research studies that are defined as controlled nevertheless mix different therapeutic interventions. An example would be a comparison of hypnosis with guided imagery.

The International Society of Hypnosis is currently sponsoring Cochrane reviews of hypnotherapeutic interventions, including those with children.

TRAINING IN HYPNOSIS INSTRUCTION

Health professionals who wish to teach self-hypnosis should take workshops sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Hypnosis or its component sections, or by the Society for Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. The Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics also provides annual workshops to prepare health professionals for teaching self-hypnosis to children. Contact information for these organizations is provided in the sidebar on this page.

The basic workshops should include at least 22 hours of supervised practice of hypnosis techniques and didactic information. After completing such basic training, the professional should seek a mentor who, by phone or e-mail, can provide guidance and support. The professional who is developing skills in self-hypnosis instruction should also attend follow-up workshops, watch videotapes of other teachers, and read basic textbooks and hypnosis journals recommended by professional hypnosis societies.

Hypnosis board examinations are given in four areas: medicine, dentistry, psychology, and social work. The American Society of Clinical Hypnosis has developed a hypnosis certification program for professionals who use hypnosis in their practice and teaching.

Importantly, the professional who is developing skills in self-hypnosis instruction should learn self-hypnosis for him- or herself. Learning self-hypnosis is a valuable lifelong skill that provides many benefits.

THE FUTURE

We anticipate that appropriate and early training in self-hypnosis and biofeedback can enable children to learn to control autonomic responses relating to cardiovascular function. Preventive work by pediatric health professionals may include monitoring of autonomic responses early in life, identification of children most at risk because of autonomic lability, and interventions to reduce that risk via hypnosis and biofeedback training. We anticipate that laboratory and brain imaging studies will provide increasing documentation of the impacts of hypnotic suggestions on neural processing, and that Cochrane reviews will demonstrate increasing evidence for the clinical value of hypnosis.

- Barabasz A, Watkins JG. The history of hypnosis and its relevance to present-day psychotherapy. In: Hypnotherapeutic Techniques. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge; 2005:1–26.

- Rainville P, Duncan GH, Price DD, Carrier B, Bushnell MC. Pain affect encoded in human anterior cingulate but not somatosensory cortex. Science 1997; 277:968–971.

- Rainville P, Carrier B, Hofbauer RK, Bushnell MC, Duncan GH. Dissociation of sensory and affective dimensions of pain using hypnotic modulation. Pain 1999; 82:159–171.

- Raz A, Kirsch I, Pollard J, Nitkin-Kaner Y. Suggestion reduces the Stroop effect. Psychol Sci 2006; 17:91–95.

- Oakley DA, Deely Q, Halligan PW. Hypnotic depth and response to suggestion under standardized conditions and fMRI scanning. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 2007; 55:32–58.

- Yapko MD. The myths about hypnosis and a dose of reality. In: Trancework: An Introduction to the Practice of Clinical Hypnosis. New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge; 2003:25–55.

- Olness K, Libbey P. Unrecognized biologic bases of behavioral symptoms in patients referred for hypnotherapy. Am J Clin Hypn 1987; 30:1–8.

- Olness K, MacDonald JT, Uden DL. Comparison of self-hypnosis and propranolol in the treatment of juvenile classic migraine. Pediatrics 1987; 79:593–597.

- Olness K, Hall H, Rozniecki JJ, Schmidt W, Theoharides TC. Mast cell activation in children with migraine before and after training in self-regulation. Headache 1999; 39:101–107.

- Felt B, Hall H, Olness K, et al. Wart regression in children: comparison of relaxation-imagery to topical treatment and equal time interventions. Am J Clin Hypn 1998; 41:130–137.

- Ewin D. The effect of hypnosis and mindset on burns. Psychiatr Ann 1986; 16:115–118.

- Kuttner L. No Fears, No Tears: Children with Cancer Coping with Pain [videotape]. Vancouver, BC: Canadian Cancer Society; 1986.

- Kuttner L. No Fears, No Tears: 13 Years Later [videotape]. Vancouver, BC: Canadian Cancer Society; 1999.

- Olness KN. Perspectives from physician-patients. In: Fredericks LE, ed. The Use of Hypnosis in Surgery and Anesthesia: Psychological Preparation of the Surgical Patient. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 2001:212–222.

- Palsson OS, Turner MJ, Johnson DA, Burnelt CK, Whitehead WE. Hypnosis treatment for severe irritable bowel syndrome: investigation of mechanism and effects on symptoms. Dig Dis Sci 2002; 47:2605–2614.

- Novoa R, Hammonds T. Clinical hypnosis for reduction of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Cleve Clin J Med 2008; 75(Suppl 2):S44–S47.

- Kirsch I. Hypnotic enhancement of cognitive-behavioral weight loss treatments.another meta-reanalysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996; 64:517–519.

- Green JP, Lynn SJ. Hypnosis and suggestion-based approaches to smoking cessation: an examination of the evidence. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 2000; 48:195–224.

- Olness K, Kohen DP. Hypnosis and Hypnotherapy with Children. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996.

- Wester WC II, Sugarman LI, eds. Therapeutic Hypnosis with Children and Adolescents. Bethel, CT: Crown House Publishing; 2007.

- London P, Cooper LM. Norms of hypnotic susceptibility in children. Dev Psychol 1969; 1:113–124.

- Morgan AH, Hilgard JR. The Stanford Hypnotic Clinical Scale for Children. Am J Clin Hypn 1978; 21:148–169.

- Dikel W, Olness K. Self-hypnosis, biofeedback, and voluntary peripheral temperature control in children. Pediatrics 1980; 66:335–340.

- Olness KN, Conroy MM. A pilot study of voluntary control of transcutaneous PO2 by children: a brief communication. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 1985; 33:1–5.

- Hogan M, MacDonald J, Olness K. Voluntary control of auditory evoked responses by children with and without hypnosis. Am J Clin Hypn 1984; 27:91–94.

- Olness K, Culbert T, Uden D. Self-regulation of salivary immunoglobulin A by children. Pediatrics 1989; 83:66–71.

- Hall HR, Minnes L, Tosi M, Olness K. Voluntary modulation of neutrophil adhesiveness using a cyberphysiologic strategy. Int J Neurosci 1992; 63:287–297.

- Hewson-Bower B. Psychological Treatment Decreases Colds and Flu in Children by Increasing Salivary Immunoglobin A [PhD thesis]. Perth, Western Australia: Murdoch University; 1995.

- Hewson-Bower B, Drummond PD. Secretory immunoglobulin A increases during relaxation in children with and without recurrent upper respiratory tract infections. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1996; 17: 311–316.

- Bothe DA, Olness KN. The effects of a stress management technique on elementary school children [abstract]. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2006; 27:429. Abstract 5.

- Barabasz A, Watkins JG. The history of hypnosis and its relevance to present-day psychotherapy. In: Hypnotherapeutic Techniques. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge; 2005:1–26.

- Rainville P, Duncan GH, Price DD, Carrier B, Bushnell MC. Pain affect encoded in human anterior cingulate but not somatosensory cortex. Science 1997; 277:968–971.

- Rainville P, Carrier B, Hofbauer RK, Bushnell MC, Duncan GH. Dissociation of sensory and affective dimensions of pain using hypnotic modulation. Pain 1999; 82:159–171.

- Raz A, Kirsch I, Pollard J, Nitkin-Kaner Y. Suggestion reduces the Stroop effect. Psychol Sci 2006; 17:91–95.

- Oakley DA, Deely Q, Halligan PW. Hypnotic depth and response to suggestion under standardized conditions and fMRI scanning. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 2007; 55:32–58.

- Yapko MD. The myths about hypnosis and a dose of reality. In: Trancework: An Introduction to the Practice of Clinical Hypnosis. New York, NY: Brunner-Routledge; 2003:25–55.

- Olness K, Libbey P. Unrecognized biologic bases of behavioral symptoms in patients referred for hypnotherapy. Am J Clin Hypn 1987; 30:1–8.

- Olness K, MacDonald JT, Uden DL. Comparison of self-hypnosis and propranolol in the treatment of juvenile classic migraine. Pediatrics 1987; 79:593–597.

- Olness K, Hall H, Rozniecki JJ, Schmidt W, Theoharides TC. Mast cell activation in children with migraine before and after training in self-regulation. Headache 1999; 39:101–107.

- Felt B, Hall H, Olness K, et al. Wart regression in children: comparison of relaxation-imagery to topical treatment and equal time interventions. Am J Clin Hypn 1998; 41:130–137.

- Ewin D. The effect of hypnosis and mindset on burns. Psychiatr Ann 1986; 16:115–118.

- Kuttner L. No Fears, No Tears: Children with Cancer Coping with Pain [videotape]. Vancouver, BC: Canadian Cancer Society; 1986.

- Kuttner L. No Fears, No Tears: 13 Years Later [videotape]. Vancouver, BC: Canadian Cancer Society; 1999.

- Olness KN. Perspectives from physician-patients. In: Fredericks LE, ed. The Use of Hypnosis in Surgery and Anesthesia: Psychological Preparation of the Surgical Patient. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 2001:212–222.

- Palsson OS, Turner MJ, Johnson DA, Burnelt CK, Whitehead WE. Hypnosis treatment for severe irritable bowel syndrome: investigation of mechanism and effects on symptoms. Dig Dis Sci 2002; 47:2605–2614.

- Novoa R, Hammonds T. Clinical hypnosis for reduction of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Cleve Clin J Med 2008; 75(Suppl 2):S44–S47.

- Kirsch I. Hypnotic enhancement of cognitive-behavioral weight loss treatments.another meta-reanalysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996; 64:517–519.

- Green JP, Lynn SJ. Hypnosis and suggestion-based approaches to smoking cessation: an examination of the evidence. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 2000; 48:195–224.

- Olness K, Kohen DP. Hypnosis and Hypnotherapy with Children. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996.

- Wester WC II, Sugarman LI, eds. Therapeutic Hypnosis with Children and Adolescents. Bethel, CT: Crown House Publishing; 2007.

- London P, Cooper LM. Norms of hypnotic susceptibility in children. Dev Psychol 1969; 1:113–124.

- Morgan AH, Hilgard JR. The Stanford Hypnotic Clinical Scale for Children. Am J Clin Hypn 1978; 21:148–169.

- Dikel W, Olness K. Self-hypnosis, biofeedback, and voluntary peripheral temperature control in children. Pediatrics 1980; 66:335–340.

- Olness KN, Conroy MM. A pilot study of voluntary control of transcutaneous PO2 by children: a brief communication. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 1985; 33:1–5.

- Hogan M, MacDonald J, Olness K. Voluntary control of auditory evoked responses by children with and without hypnosis. Am J Clin Hypn 1984; 27:91–94.

- Olness K, Culbert T, Uden D. Self-regulation of salivary immunoglobulin A by children. Pediatrics 1989; 83:66–71.

- Hall HR, Minnes L, Tosi M, Olness K. Voluntary modulation of neutrophil adhesiveness using a cyberphysiologic strategy. Int J Neurosci 1992; 63:287–297.

- Hewson-Bower B. Psychological Treatment Decreases Colds and Flu in Children by Increasing Salivary Immunoglobin A [PhD thesis]. Perth, Western Australia: Murdoch University; 1995.

- Hewson-Bower B, Drummond PD. Secretory immunoglobulin A increases during relaxation in children with and without recurrent upper respiratory tract infections. J Dev Behav Pediatr 1996; 17: 311–316.

- Bothe DA, Olness KN. The effects of a stress management technique on elementary school children [abstract]. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2006; 27:429. Abstract 5.