User login

VIENNA – Depressed patients with a high-status job appear to be significantly less responsive to antidepressant therapy than other workers, Joseph Zohar, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

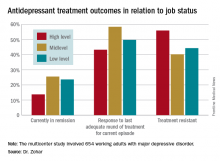

He presented a multicenter study of 654 Austrian, Israeli, Belgian, and Italian working adults with major depressive disorder. Those categorized as having a high occupational level were significantly less likely to have responded to the most recent trial of antidepressant medication for their current episode. They also had a significantly higher rate of treatment-resistant depression as defined by nonresponse to at least two previous adequate treatment trials, compared with the patients with mid- or low-level occupations.

“These results show that the need for precise prescribing is not only related to the symptoms and genetics but also to occupational level. One might need to prescribe different medication for the same disorder and need to take into account the occupational level in order to reach optimum effect,” he continued.

He and his coinvestigators categorized occupational level according to Hollingshead’s Occupational Scale, a tool widely used by sociologists. Occupational level is a different concept from socioeconomic status. It incorporates prestige, entry qualifications, job responsibilities, and skill requirements – as well as earnings. Examples of high occupational level jobs in this construct include physicians, engineers, architects, scientists, lawyers, CEOs, and professors.

Fifty-one percent of the study participants were classified as having high-status occupations, with the rest evenly divided between mid- and low-level occupations. Only 43.2% of patients in the high-level group had responded to their last treatment episode based upon clinical judgment and a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score of 17 or less, compared with 58.4% of patients with mid- and 49.7% with low-level jobs.

At this point the explanation for the observed relationship between occupation level and antidepressant treatment response remains speculative. This is the first large study of its kind, and the results require confirmation. If the findings hold up, the results could have important implications for employers, who might want to discourage patients with high-status jobs and a history of treatment-resistant depression from particularly high work stress environments in order to reduce depression-related disability in the workplace, according to the psychiatrist.

Potential explanations for the findings include the possibility that depressed patients in high-level occupations are more likely to have poor illness acceptance, be less adherent to prescribed medications, or possess certain personality, cognitive, or behavioral differences that predispose to poor treatment outcome.

The study was funded by the ECNP’s Expert Platform on Mental Health – Focus on Depression. Dr. Zohar reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

VIENNA – Depressed patients with a high-status job appear to be significantly less responsive to antidepressant therapy than other workers, Joseph Zohar, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

He presented a multicenter study of 654 Austrian, Israeli, Belgian, and Italian working adults with major depressive disorder. Those categorized as having a high occupational level were significantly less likely to have responded to the most recent trial of antidepressant medication for their current episode. They also had a significantly higher rate of treatment-resistant depression as defined by nonresponse to at least two previous adequate treatment trials, compared with the patients with mid- or low-level occupations.

“These results show that the need for precise prescribing is not only related to the symptoms and genetics but also to occupational level. One might need to prescribe different medication for the same disorder and need to take into account the occupational level in order to reach optimum effect,” he continued.

He and his coinvestigators categorized occupational level according to Hollingshead’s Occupational Scale, a tool widely used by sociologists. Occupational level is a different concept from socioeconomic status. It incorporates prestige, entry qualifications, job responsibilities, and skill requirements – as well as earnings. Examples of high occupational level jobs in this construct include physicians, engineers, architects, scientists, lawyers, CEOs, and professors.

Fifty-one percent of the study participants were classified as having high-status occupations, with the rest evenly divided between mid- and low-level occupations. Only 43.2% of patients in the high-level group had responded to their last treatment episode based upon clinical judgment and a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score of 17 or less, compared with 58.4% of patients with mid- and 49.7% with low-level jobs.

At this point the explanation for the observed relationship between occupation level and antidepressant treatment response remains speculative. This is the first large study of its kind, and the results require confirmation. If the findings hold up, the results could have important implications for employers, who might want to discourage patients with high-status jobs and a history of treatment-resistant depression from particularly high work stress environments in order to reduce depression-related disability in the workplace, according to the psychiatrist.

Potential explanations for the findings include the possibility that depressed patients in high-level occupations are more likely to have poor illness acceptance, be less adherent to prescribed medications, or possess certain personality, cognitive, or behavioral differences that predispose to poor treatment outcome.

The study was funded by the ECNP’s Expert Platform on Mental Health – Focus on Depression. Dr. Zohar reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

VIENNA – Depressed patients with a high-status job appear to be significantly less responsive to antidepressant therapy than other workers, Joseph Zohar, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

He presented a multicenter study of 654 Austrian, Israeli, Belgian, and Italian working adults with major depressive disorder. Those categorized as having a high occupational level were significantly less likely to have responded to the most recent trial of antidepressant medication for their current episode. They also had a significantly higher rate of treatment-resistant depression as defined by nonresponse to at least two previous adequate treatment trials, compared with the patients with mid- or low-level occupations.

“These results show that the need for precise prescribing is not only related to the symptoms and genetics but also to occupational level. One might need to prescribe different medication for the same disorder and need to take into account the occupational level in order to reach optimum effect,” he continued.

He and his coinvestigators categorized occupational level according to Hollingshead’s Occupational Scale, a tool widely used by sociologists. Occupational level is a different concept from socioeconomic status. It incorporates prestige, entry qualifications, job responsibilities, and skill requirements – as well as earnings. Examples of high occupational level jobs in this construct include physicians, engineers, architects, scientists, lawyers, CEOs, and professors.

Fifty-one percent of the study participants were classified as having high-status occupations, with the rest evenly divided between mid- and low-level occupations. Only 43.2% of patients in the high-level group had responded to their last treatment episode based upon clinical judgment and a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score of 17 or less, compared with 58.4% of patients with mid- and 49.7% with low-level jobs.

At this point the explanation for the observed relationship between occupation level and antidepressant treatment response remains speculative. This is the first large study of its kind, and the results require confirmation. If the findings hold up, the results could have important implications for employers, who might want to discourage patients with high-status jobs and a history of treatment-resistant depression from particularly high work stress environments in order to reduce depression-related disability in the workplace, according to the psychiatrist.

Potential explanations for the findings include the possibility that depressed patients in high-level occupations are more likely to have poor illness acceptance, be less adherent to prescribed medications, or possess certain personality, cognitive, or behavioral differences that predispose to poor treatment outcome.

The study was funded by the ECNP’s Expert Platform on Mental Health – Focus on Depression. Dr. Zohar reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

AT THE ECNP CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Fifty-six percent of patients with high-status occupations who were treated for major depression were classified as treatment resistant, compared with 40% of patients with midlevel occupations and 44% with low-level occupations.

Data source: A study of 654 working adults with major depression in four countries.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Expert Platform on Mental Health Focus on Depression. The presenter reported having no relevant financial conflicts.