User login

CASE Depressed and suicidal

Police arrive at the home of Mr. H, age 50, after his wife calls 911. She reports he has depression and she saw him in bed brandishing a firearm as if he wanted to hurt himself. Upon arrival, the officers enter the house and find Mr. H in bed without a firearm. Mr. H says little to the officers about the alleged events, but acknowledges he has depression and is willing to go the hospital for further evaluation. Neither his wife nor the officers locate a firearm in the home.

EVALUATION Emergency detention

In the emergency department (ED), Mr. H’s laboratory results and physical examination findings are normal. He acknowledges feeling depressed over the past 2 weeks. Though he cannot identify any precipitants, he says he has experienced anhedonia, lack of appetite, decreased energy, and changes in his sleep patterns. When asked about the day’s events concerning the firearm, Mr. H becomes guarded and does not give a clear answer regarding having thoughts of suicide.

The evaluating psychiatrist obtains collateral from Mr. H’s wife and reviews his medical records. There are no active prescriptions on file and the psychiatrist notices that last year there was a suicide attempt involving a firearm. Following that episode, Mr. H was hospitalized, treated with sertraline 50 mg/d, and discharged with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. There was no legal or substance abuse history.

In the ED, the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric evaluation, including a suicide risk assessment, and determines Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life. Mr. H’s psychiatrist explains there are 2 treatment options: to be admitted to the hospital or to be discharged. The psychiatrist recommends hospital admission to Mr. H for his safety and stabilization. Mr. H says he prefers to return home.

Because the psychiatrist believes Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life and there is no less restrictive setting for treatment, he implements an emergency detention. In Ohio, this allows Mr. H to be held in the hospital for no more than 3 court days in accordance with state law. Before Mr. H’s emergency detention periods ends, the psychiatrist will need to decide whether Mr. H can be safely discharged. If the psychiatrist determines that Mr. H still needs treatment, the court will be petitioned for a civil commitment hearing.

[polldaddy:11189291]

The author’s observations

In some cases, courts allow information a psychiatrist does not directly obtain from a patient to be admitted as testimony in a civil commitment hearing. However, some jurisdictions consider sources of information not obtained directly from the patient as hearsay and thus inadmissible.1 Though each source listed may provide credible information that could be presented at a hearing, the psychiatrist should discuss with the patient the information obtained from these sources to ensure it is admissable.2 A discussion with Mr. H about the factors that led to his hospital arrival will avoid the psychiatrist’s reliance on what another person has heard or seen when providing testimony. Even when a psychiatrist is not faced with an issue of admissibility, caution must be taken with third-party reports.3

TREATMENT Civil commitment hearing

Before the emergency detention period expires, Mr. H’s psychiatrist determines that he remains at imminent risk of self-harm. To continue hospitalization, the psychiatrist files a petition for civil commitment and testifies at the commitment hearing. He reports that Mr. H suffers from a substantial mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The psychiatrist also testifies that the least restrictive environment for treatment continues to be inpatient hospitalization, because Mr. H is still at imminent risk of harming himself.

Continue to: Following the psychiatrist's...

Following the psychiatrist’s testimony, the magistrate finds that Mr. H is a mentally ill person subject to hospitalization given his mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The magistrate orders that Mr. H be civilly committed to the hospital.

[polldaddy:11189293]

The author’s observations

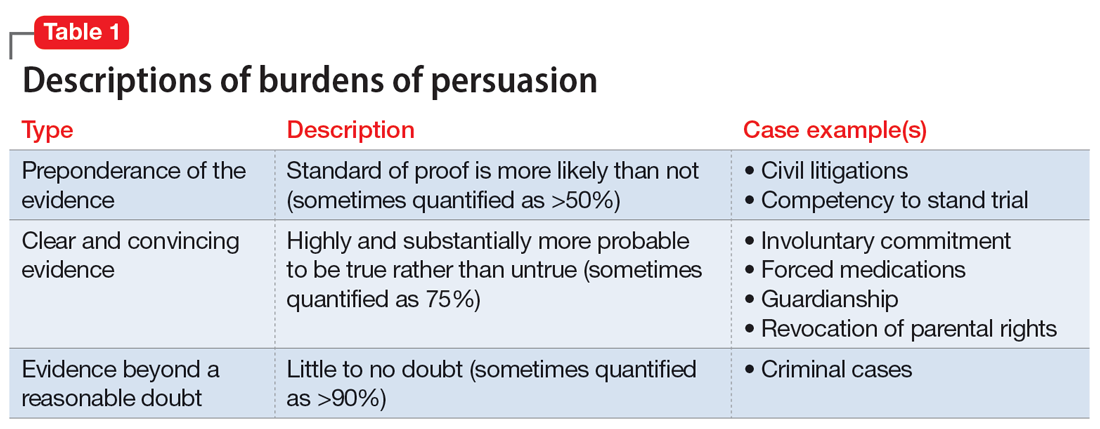

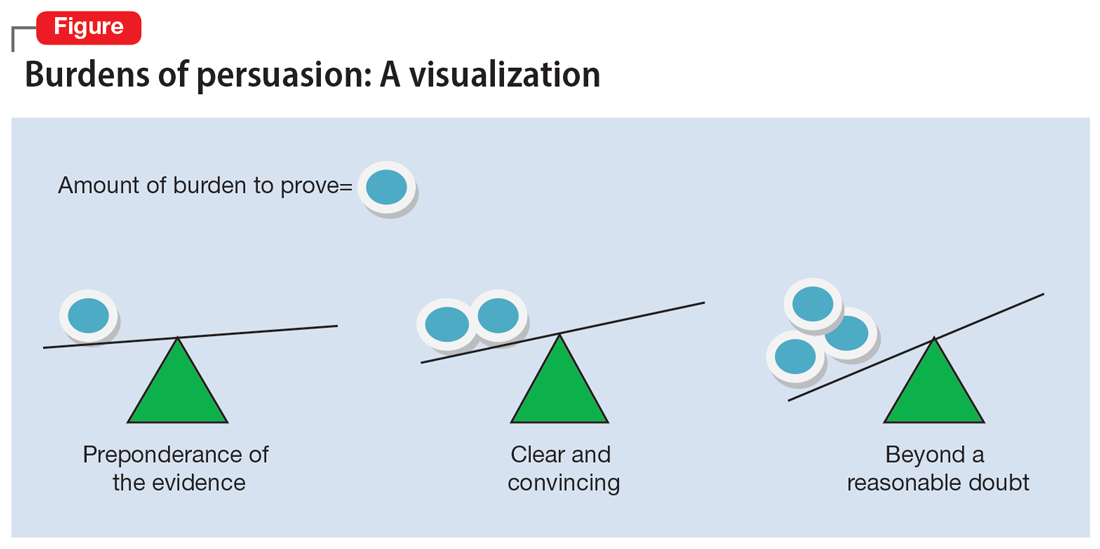

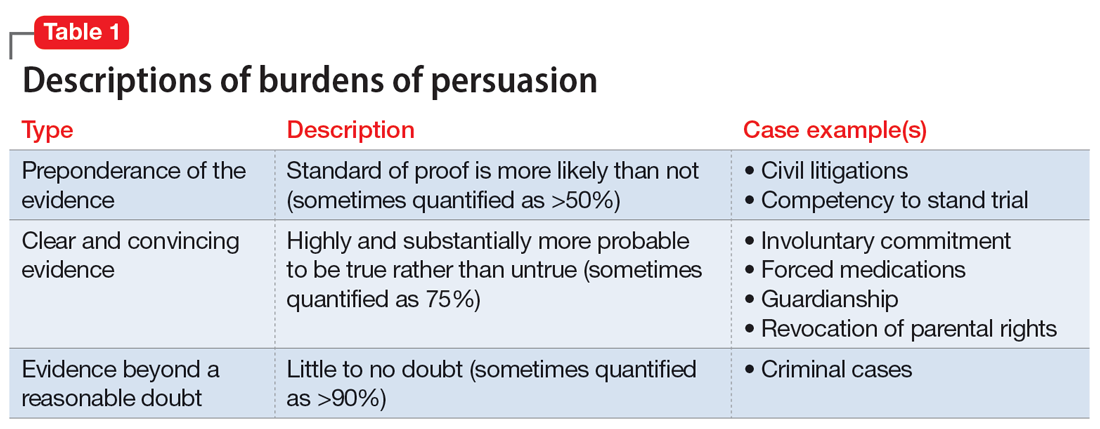

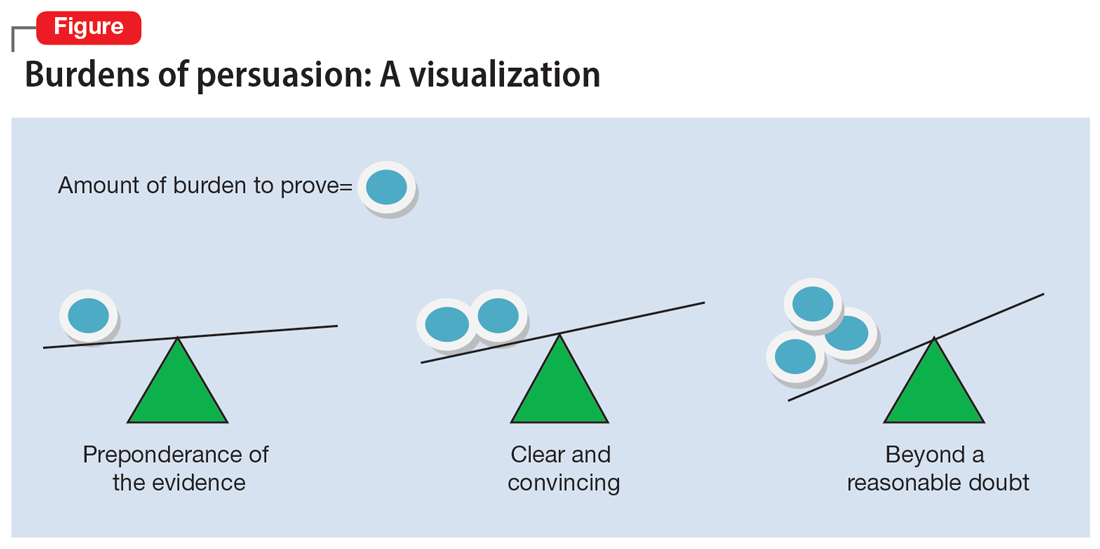

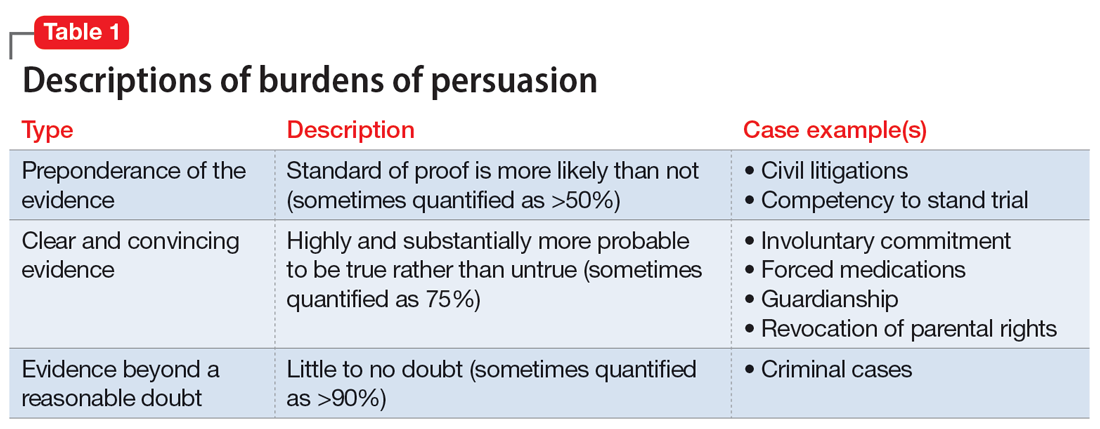

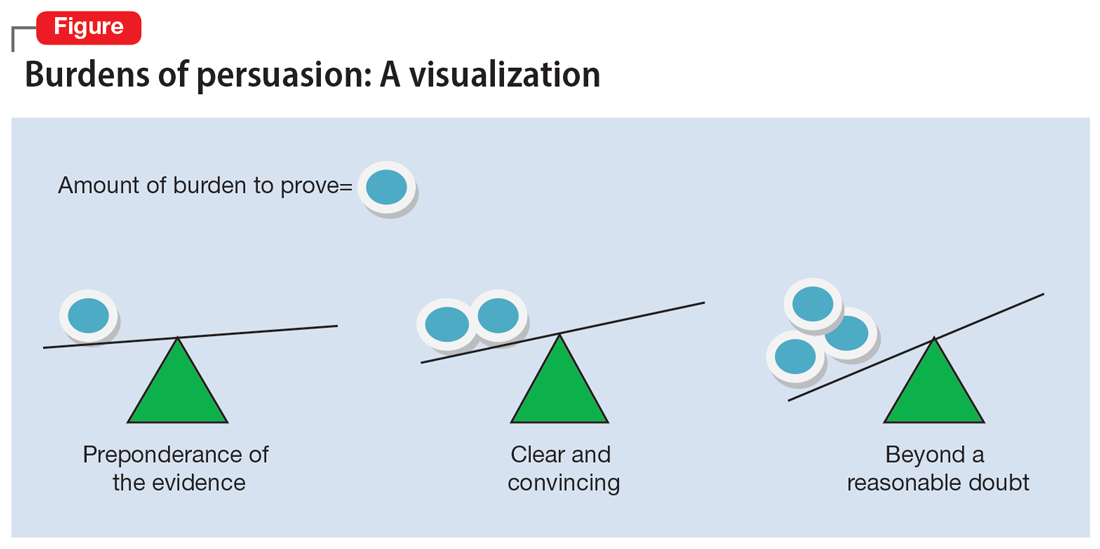

The psychiatrist’s testimony mirrors the language regarding civil commitment in the Ohio Revised Code.4 Other elements considered for mental illness in Ohio are a substantial disorder of memory, thought, orientation, or perception that grossly impairs one’s capacity to recognize reality or meet the demands of life.4 The definition of what constitutes a mental disorder varies by state, but the burden of persuasion—the standard by which the court must be convinced—is generally uniform.5 In the 1979 case Addington v Texas, the United States Supreme Court concluded that in a civil commitment hearing, the minimum standard of proof for involuntary commitment must be clear and convincing evidence.6 Neither medical certainty nor substantial probability are burdens of persuasions.6 Instead, these terms may be presented in a forensic report when an examiner outlines their opinion. Table 1 and the Figure provide more detail on burdens of persuasion.

TREATMENT Civil commitment and patient rights

At a regularly scheduled treatment team meeting, the team informs Mr. H that he has been civilly committed for further treatment. Mr. H becomes upset and tells the team the decision is a complete violation of his rights. After a long rant, Mr. H walks out of the room, saying, “I did not even know when this hearing was.” A member of the treatment team becomes concerned that Mr. H may not have been notified of the hearing.

[polldaddy:11189294]

The author’s observations

It is not clear if Mr. H had been notified of his civil commitment hearing. If Mr. H had not been notified, his rights would have been compromised. Lessard v Schmidt (1972) outlined that individuals involved in a civil commitment hearing should be afforded the same rights as those involved in criminal proceedings.7 Mr. H should have been notified of his hearing and afforded the opportunity to have the assignment of counsel, the right to appear, the right to testify, the right to present witnesses and other evidence, and the right to confront witnesses.

Without notification of the hearing, the only right that would have remained intact for Mr. H would have been the assignment of counsel in his absence and without his knowledge. If Mr. H had been notified of the hearing and did not want to attend, yet still desired legal counsel, he could have waived his presence voluntarily after discussing this option with his attorney.8,9

Continue to: OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

During his 10-day stay, Mr. H is treated with sertraline 50 mg/d and engages in individual and group therapy. He shows noticeable improvement in his depressive symptoms and reports having no thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The treatment team determines it is appropriate to discharge him home (the firearm was never found) and involves his wife in safety planning and follow-up care. On the day of his discharge, Mr. H reflects on his treatment and civil commitment. He says, “I did not know a judge could order me to be hospitalized.”

[polldaddy:11189297]

The author’s observations

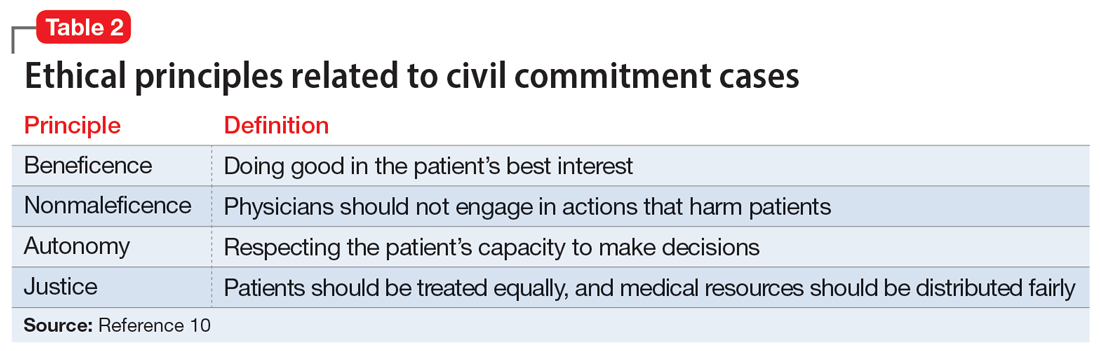

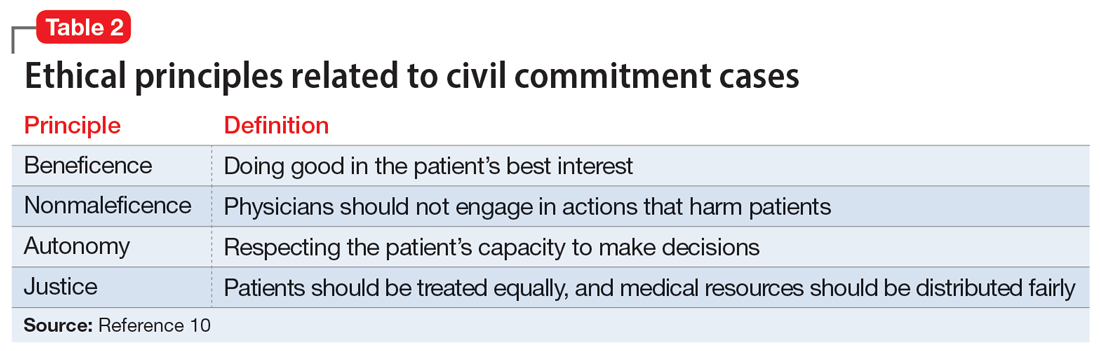

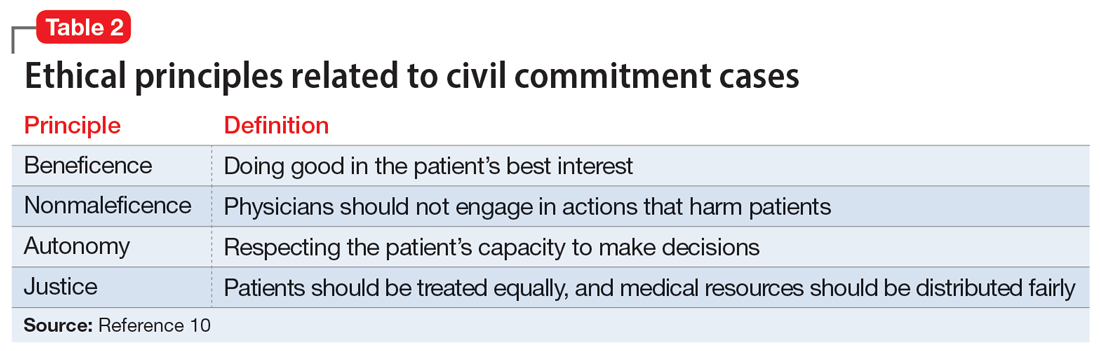

The physician’s decision to pursue civil commitment is best described by the legal doctrines of police powers and parens patriae. Other relevant ethical principles are described in Table 2.10

Though ethical principles may play a role in civil commitment, parens patriae and police powers is the answer with respect to the State.11Parens patriae is Latin for the “parent of the country” and grants the State the power to protect those residents who are most vulnerable. Police power is the authority of the State to enact and enforce rules that limit the rights of individuals for the greater good of ensuring health, safety, and welfare of all citizens.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists are entrusted with recognizing when a patient, due to mental illness, is a danger to themselves or others and in need of treatment. After an emergency detention period, if the patient remains a danger to themselves or others and does not want to voluntarily receive treatment, a court hearing is required. As an expert witness, the treating psychiatrist should know the factors of law in their jurisdiction that determine civil commitment.

Related Resources

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/ centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-violenceprevention-and-policy/research/extreme-risk-protectionorders/

- Gutheil TG. The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

- Landmark Cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://www.aapl.org/landmark-cases

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for Civil Commitment. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Thatcher BT, Mossman D. Testifying for civil commitment: help unwilling patients get the treatment they need. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(11):51-56.

3. Marett CP, Mossman D. What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):21-25,33.

4. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01 (2018).

5. The Burden of Proof. University of Minnesota. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/chapter/2-4-the-burden-of-proof/

6. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

8. Cook J. Good lawyering and bad role models: the role of respondent’s counsel in a civil commitment hearing. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 2000;14(1):179-195.

9. Ferris CE. The search for due process in civil commitment hearings: how procedural realities have altered substantive standards. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2008;61(3):959-981.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice. 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/civil-commitment-mental-health-care-continuum-historical-trends-principles-law

11. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Profession. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2018.

CASE Depressed and suicidal

Police arrive at the home of Mr. H, age 50, after his wife calls 911. She reports he has depression and she saw him in bed brandishing a firearm as if he wanted to hurt himself. Upon arrival, the officers enter the house and find Mr. H in bed without a firearm. Mr. H says little to the officers about the alleged events, but acknowledges he has depression and is willing to go the hospital for further evaluation. Neither his wife nor the officers locate a firearm in the home.

EVALUATION Emergency detention

In the emergency department (ED), Mr. H’s laboratory results and physical examination findings are normal. He acknowledges feeling depressed over the past 2 weeks. Though he cannot identify any precipitants, he says he has experienced anhedonia, lack of appetite, decreased energy, and changes in his sleep patterns. When asked about the day’s events concerning the firearm, Mr. H becomes guarded and does not give a clear answer regarding having thoughts of suicide.

The evaluating psychiatrist obtains collateral from Mr. H’s wife and reviews his medical records. There are no active prescriptions on file and the psychiatrist notices that last year there was a suicide attempt involving a firearm. Following that episode, Mr. H was hospitalized, treated with sertraline 50 mg/d, and discharged with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. There was no legal or substance abuse history.

In the ED, the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric evaluation, including a suicide risk assessment, and determines Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life. Mr. H’s psychiatrist explains there are 2 treatment options: to be admitted to the hospital or to be discharged. The psychiatrist recommends hospital admission to Mr. H for his safety and stabilization. Mr. H says he prefers to return home.

Because the psychiatrist believes Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life and there is no less restrictive setting for treatment, he implements an emergency detention. In Ohio, this allows Mr. H to be held in the hospital for no more than 3 court days in accordance with state law. Before Mr. H’s emergency detention periods ends, the psychiatrist will need to decide whether Mr. H can be safely discharged. If the psychiatrist determines that Mr. H still needs treatment, the court will be petitioned for a civil commitment hearing.

[polldaddy:11189291]

The author’s observations

In some cases, courts allow information a psychiatrist does not directly obtain from a patient to be admitted as testimony in a civil commitment hearing. However, some jurisdictions consider sources of information not obtained directly from the patient as hearsay and thus inadmissible.1 Though each source listed may provide credible information that could be presented at a hearing, the psychiatrist should discuss with the patient the information obtained from these sources to ensure it is admissable.2 A discussion with Mr. H about the factors that led to his hospital arrival will avoid the psychiatrist’s reliance on what another person has heard or seen when providing testimony. Even when a psychiatrist is not faced with an issue of admissibility, caution must be taken with third-party reports.3

TREATMENT Civil commitment hearing

Before the emergency detention period expires, Mr. H’s psychiatrist determines that he remains at imminent risk of self-harm. To continue hospitalization, the psychiatrist files a petition for civil commitment and testifies at the commitment hearing. He reports that Mr. H suffers from a substantial mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The psychiatrist also testifies that the least restrictive environment for treatment continues to be inpatient hospitalization, because Mr. H is still at imminent risk of harming himself.

Continue to: Following the psychiatrist's...

Following the psychiatrist’s testimony, the magistrate finds that Mr. H is a mentally ill person subject to hospitalization given his mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The magistrate orders that Mr. H be civilly committed to the hospital.

[polldaddy:11189293]

The author’s observations

The psychiatrist’s testimony mirrors the language regarding civil commitment in the Ohio Revised Code.4 Other elements considered for mental illness in Ohio are a substantial disorder of memory, thought, orientation, or perception that grossly impairs one’s capacity to recognize reality or meet the demands of life.4 The definition of what constitutes a mental disorder varies by state, but the burden of persuasion—the standard by which the court must be convinced—is generally uniform.5 In the 1979 case Addington v Texas, the United States Supreme Court concluded that in a civil commitment hearing, the minimum standard of proof for involuntary commitment must be clear and convincing evidence.6 Neither medical certainty nor substantial probability are burdens of persuasions.6 Instead, these terms may be presented in a forensic report when an examiner outlines their opinion. Table 1 and the Figure provide more detail on burdens of persuasion.

TREATMENT Civil commitment and patient rights

At a regularly scheduled treatment team meeting, the team informs Mr. H that he has been civilly committed for further treatment. Mr. H becomes upset and tells the team the decision is a complete violation of his rights. After a long rant, Mr. H walks out of the room, saying, “I did not even know when this hearing was.” A member of the treatment team becomes concerned that Mr. H may not have been notified of the hearing.

[polldaddy:11189294]

The author’s observations

It is not clear if Mr. H had been notified of his civil commitment hearing. If Mr. H had not been notified, his rights would have been compromised. Lessard v Schmidt (1972) outlined that individuals involved in a civil commitment hearing should be afforded the same rights as those involved in criminal proceedings.7 Mr. H should have been notified of his hearing and afforded the opportunity to have the assignment of counsel, the right to appear, the right to testify, the right to present witnesses and other evidence, and the right to confront witnesses.

Without notification of the hearing, the only right that would have remained intact for Mr. H would have been the assignment of counsel in his absence and without his knowledge. If Mr. H had been notified of the hearing and did not want to attend, yet still desired legal counsel, he could have waived his presence voluntarily after discussing this option with his attorney.8,9

Continue to: OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

During his 10-day stay, Mr. H is treated with sertraline 50 mg/d and engages in individual and group therapy. He shows noticeable improvement in his depressive symptoms and reports having no thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The treatment team determines it is appropriate to discharge him home (the firearm was never found) and involves his wife in safety planning and follow-up care. On the day of his discharge, Mr. H reflects on his treatment and civil commitment. He says, “I did not know a judge could order me to be hospitalized.”

[polldaddy:11189297]

The author’s observations

The physician’s decision to pursue civil commitment is best described by the legal doctrines of police powers and parens patriae. Other relevant ethical principles are described in Table 2.10

Though ethical principles may play a role in civil commitment, parens patriae and police powers is the answer with respect to the State.11Parens patriae is Latin for the “parent of the country” and grants the State the power to protect those residents who are most vulnerable. Police power is the authority of the State to enact and enforce rules that limit the rights of individuals for the greater good of ensuring health, safety, and welfare of all citizens.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists are entrusted with recognizing when a patient, due to mental illness, is a danger to themselves or others and in need of treatment. After an emergency detention period, if the patient remains a danger to themselves or others and does not want to voluntarily receive treatment, a court hearing is required. As an expert witness, the treating psychiatrist should know the factors of law in their jurisdiction that determine civil commitment.

Related Resources

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/ centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-violenceprevention-and-policy/research/extreme-risk-protectionorders/

- Gutheil TG. The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

- Landmark Cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://www.aapl.org/landmark-cases

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

CASE Depressed and suicidal

Police arrive at the home of Mr. H, age 50, after his wife calls 911. She reports he has depression and she saw him in bed brandishing a firearm as if he wanted to hurt himself. Upon arrival, the officers enter the house and find Mr. H in bed without a firearm. Mr. H says little to the officers about the alleged events, but acknowledges he has depression and is willing to go the hospital for further evaluation. Neither his wife nor the officers locate a firearm in the home.

EVALUATION Emergency detention

In the emergency department (ED), Mr. H’s laboratory results and physical examination findings are normal. He acknowledges feeling depressed over the past 2 weeks. Though he cannot identify any precipitants, he says he has experienced anhedonia, lack of appetite, decreased energy, and changes in his sleep patterns. When asked about the day’s events concerning the firearm, Mr. H becomes guarded and does not give a clear answer regarding having thoughts of suicide.

The evaluating psychiatrist obtains collateral from Mr. H’s wife and reviews his medical records. There are no active prescriptions on file and the psychiatrist notices that last year there was a suicide attempt involving a firearm. Following that episode, Mr. H was hospitalized, treated with sertraline 50 mg/d, and discharged with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. There was no legal or substance abuse history.

In the ED, the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric evaluation, including a suicide risk assessment, and determines Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life. Mr. H’s psychiatrist explains there are 2 treatment options: to be admitted to the hospital or to be discharged. The psychiatrist recommends hospital admission to Mr. H for his safety and stabilization. Mr. H says he prefers to return home.

Because the psychiatrist believes Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life and there is no less restrictive setting for treatment, he implements an emergency detention. In Ohio, this allows Mr. H to be held in the hospital for no more than 3 court days in accordance with state law. Before Mr. H’s emergency detention periods ends, the psychiatrist will need to decide whether Mr. H can be safely discharged. If the psychiatrist determines that Mr. H still needs treatment, the court will be petitioned for a civil commitment hearing.

[polldaddy:11189291]

The author’s observations

In some cases, courts allow information a psychiatrist does not directly obtain from a patient to be admitted as testimony in a civil commitment hearing. However, some jurisdictions consider sources of information not obtained directly from the patient as hearsay and thus inadmissible.1 Though each source listed may provide credible information that could be presented at a hearing, the psychiatrist should discuss with the patient the information obtained from these sources to ensure it is admissable.2 A discussion with Mr. H about the factors that led to his hospital arrival will avoid the psychiatrist’s reliance on what another person has heard or seen when providing testimony. Even when a psychiatrist is not faced with an issue of admissibility, caution must be taken with third-party reports.3

TREATMENT Civil commitment hearing

Before the emergency detention period expires, Mr. H’s psychiatrist determines that he remains at imminent risk of self-harm. To continue hospitalization, the psychiatrist files a petition for civil commitment and testifies at the commitment hearing. He reports that Mr. H suffers from a substantial mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The psychiatrist also testifies that the least restrictive environment for treatment continues to be inpatient hospitalization, because Mr. H is still at imminent risk of harming himself.

Continue to: Following the psychiatrist's...

Following the psychiatrist’s testimony, the magistrate finds that Mr. H is a mentally ill person subject to hospitalization given his mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The magistrate orders that Mr. H be civilly committed to the hospital.

[polldaddy:11189293]

The author’s observations

The psychiatrist’s testimony mirrors the language regarding civil commitment in the Ohio Revised Code.4 Other elements considered for mental illness in Ohio are a substantial disorder of memory, thought, orientation, or perception that grossly impairs one’s capacity to recognize reality or meet the demands of life.4 The definition of what constitutes a mental disorder varies by state, but the burden of persuasion—the standard by which the court must be convinced—is generally uniform.5 In the 1979 case Addington v Texas, the United States Supreme Court concluded that in a civil commitment hearing, the minimum standard of proof for involuntary commitment must be clear and convincing evidence.6 Neither medical certainty nor substantial probability are burdens of persuasions.6 Instead, these terms may be presented in a forensic report when an examiner outlines their opinion. Table 1 and the Figure provide more detail on burdens of persuasion.

TREATMENT Civil commitment and patient rights

At a regularly scheduled treatment team meeting, the team informs Mr. H that he has been civilly committed for further treatment. Mr. H becomes upset and tells the team the decision is a complete violation of his rights. After a long rant, Mr. H walks out of the room, saying, “I did not even know when this hearing was.” A member of the treatment team becomes concerned that Mr. H may not have been notified of the hearing.

[polldaddy:11189294]

The author’s observations

It is not clear if Mr. H had been notified of his civil commitment hearing. If Mr. H had not been notified, his rights would have been compromised. Lessard v Schmidt (1972) outlined that individuals involved in a civil commitment hearing should be afforded the same rights as those involved in criminal proceedings.7 Mr. H should have been notified of his hearing and afforded the opportunity to have the assignment of counsel, the right to appear, the right to testify, the right to present witnesses and other evidence, and the right to confront witnesses.

Without notification of the hearing, the only right that would have remained intact for Mr. H would have been the assignment of counsel in his absence and without his knowledge. If Mr. H had been notified of the hearing and did not want to attend, yet still desired legal counsel, he could have waived his presence voluntarily after discussing this option with his attorney.8,9

Continue to: OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

During his 10-day stay, Mr. H is treated with sertraline 50 mg/d and engages in individual and group therapy. He shows noticeable improvement in his depressive symptoms and reports having no thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The treatment team determines it is appropriate to discharge him home (the firearm was never found) and involves his wife in safety planning and follow-up care. On the day of his discharge, Mr. H reflects on his treatment and civil commitment. He says, “I did not know a judge could order me to be hospitalized.”

[polldaddy:11189297]

The author’s observations

The physician’s decision to pursue civil commitment is best described by the legal doctrines of police powers and parens patriae. Other relevant ethical principles are described in Table 2.10

Though ethical principles may play a role in civil commitment, parens patriae and police powers is the answer with respect to the State.11Parens patriae is Latin for the “parent of the country” and grants the State the power to protect those residents who are most vulnerable. Police power is the authority of the State to enact and enforce rules that limit the rights of individuals for the greater good of ensuring health, safety, and welfare of all citizens.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists are entrusted with recognizing when a patient, due to mental illness, is a danger to themselves or others and in need of treatment. After an emergency detention period, if the patient remains a danger to themselves or others and does not want to voluntarily receive treatment, a court hearing is required. As an expert witness, the treating psychiatrist should know the factors of law in their jurisdiction that determine civil commitment.

Related Resources

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/ centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-violenceprevention-and-policy/research/extreme-risk-protectionorders/

- Gutheil TG. The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

- Landmark Cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://www.aapl.org/landmark-cases

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for Civil Commitment. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Thatcher BT, Mossman D. Testifying for civil commitment: help unwilling patients get the treatment they need. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(11):51-56.

3. Marett CP, Mossman D. What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):21-25,33.

4. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01 (2018).

5. The Burden of Proof. University of Minnesota. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/chapter/2-4-the-burden-of-proof/

6. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

8. Cook J. Good lawyering and bad role models: the role of respondent’s counsel in a civil commitment hearing. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 2000;14(1):179-195.

9. Ferris CE. The search for due process in civil commitment hearings: how procedural realities have altered substantive standards. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2008;61(3):959-981.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice. 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/civil-commitment-mental-health-care-continuum-historical-trends-principles-law

11. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Profession. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2018.

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for Civil Commitment. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Thatcher BT, Mossman D. Testifying for civil commitment: help unwilling patients get the treatment they need. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(11):51-56.

3. Marett CP, Mossman D. What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):21-25,33.

4. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01 (2018).

5. The Burden of Proof. University of Minnesota. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/chapter/2-4-the-burden-of-proof/

6. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

8. Cook J. Good lawyering and bad role models: the role of respondent’s counsel in a civil commitment hearing. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 2000;14(1):179-195.

9. Ferris CE. The search for due process in civil commitment hearings: how procedural realities have altered substantive standards. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2008;61(3):959-981.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice. 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/civil-commitment-mental-health-care-continuum-historical-trends-principles-law

11. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Profession. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2018.