User login

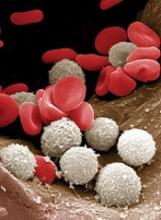

A portable device could be used to monitor patients’ white blood cell (WBC) levels at home, without the need for blood samples, according to researchers.

The team created a prototype that records video of blood cells flowing through capillaries just below the skin surface at the base of the fingernail.

The group is developing a computer algorithm that, in early testing, has been able to analyze the videos and determine if WBC levels are too low.

The researchers believe this type of device could be used to prevent infections among chemotherapy recipients.

“Our vision is that patients will have this portable device that they can take home, and they can monitor daily how they are reacting to the treatment,” said Carlos Castro-Gonzalez, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“If they go below the [safe WBC] threshold, then preventive treatment can be deployed.”

Dr Castro-Gonzalez and his colleagues described their prototype, and the testing of it, in Scientific Reports.

The device consists of a wide-field microscope that emits blue light, which penetrates about 50 to 150 microns below the skin and is reflected back to a video camera.

The researchers decided to image the skin at the base of the nail because the capillaries there are very close to the skin surface. These capillaries are so narrow that WBCs must squeeze through one at a time, making them easier to see.

The researchers tested the device in 11 patients at various points during their chemotherapy treatment.

The device does not provide precise WBC counts but allowed the team to differentiate cases of severe neutropenia (<500 neutrophils per μL) from non-neutropenic cases (>1500 neutrophils per μL).

To obtain enough data to make these classifications, the researchers recorded 1 minute of video per patient. Three blinded human assistants then watched the videos and noted whenever a WBC passed by.

However, since submitting their paper, the researchers have been developing a computer algorithm to perform the same task automatically.

“Based on the feature-set that our human raters identified, we are now developing an AI and machine-vision algorithm, with preliminary results that indicate the same accuracy as the raters,” said study author Aurélien Bourquard, PhD, of MIT.

The researchers have applied for patents on the technology and launched a company called Leuko, which is working on commercializing the technology with help from MIT.

To move the technology further toward commercialization, the researchers are building a new automated prototype.

“Automating the measurement process is key to making a viable home-use device,” said study author Ian Butterworth, of MIT. “The imaging needs to take place in the right spot on the patient’s finger, and the operation of the device must be straightforward.”

Using this new prototype, the researchers plan to test the device with additional cancer patients. And the team is investigating whether they can get accurate results with shorter lengths of video.

They also plan to adapt the technology so it can generate more precise WBC counts, which would make it useful for monitoring bone marrow transplant recipients or people with certain infectious diseases, Dr Castro-Gonzalez said.

This could also make it possible to determine whether chemotherapy patients can receive their next dose sooner than usual.

“There is a balancing act that oncologists must do,” said study author Alvaro Sanchez-Ferro, MD, of Centro Integral en Neurociencias A.C. HM CINAC in Madrid, Spain.

“Normally, doctors want to make chemotherapy as intensive as possible but without getting people too immunosuppressed. Current 21-day cycles are based on statistics of what most patients can take, but if you are ready early, then they can potentially bring you back early, and that can translate into better survival.”

A portable device could be used to monitor patients’ white blood cell (WBC) levels at home, without the need for blood samples, according to researchers.

The team created a prototype that records video of blood cells flowing through capillaries just below the skin surface at the base of the fingernail.

The group is developing a computer algorithm that, in early testing, has been able to analyze the videos and determine if WBC levels are too low.

The researchers believe this type of device could be used to prevent infections among chemotherapy recipients.

“Our vision is that patients will have this portable device that they can take home, and they can monitor daily how they are reacting to the treatment,” said Carlos Castro-Gonzalez, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“If they go below the [safe WBC] threshold, then preventive treatment can be deployed.”

Dr Castro-Gonzalez and his colleagues described their prototype, and the testing of it, in Scientific Reports.

The device consists of a wide-field microscope that emits blue light, which penetrates about 50 to 150 microns below the skin and is reflected back to a video camera.

The researchers decided to image the skin at the base of the nail because the capillaries there are very close to the skin surface. These capillaries are so narrow that WBCs must squeeze through one at a time, making them easier to see.

The researchers tested the device in 11 patients at various points during their chemotherapy treatment.

The device does not provide precise WBC counts but allowed the team to differentiate cases of severe neutropenia (<500 neutrophils per μL) from non-neutropenic cases (>1500 neutrophils per μL).

To obtain enough data to make these classifications, the researchers recorded 1 minute of video per patient. Three blinded human assistants then watched the videos and noted whenever a WBC passed by.

However, since submitting their paper, the researchers have been developing a computer algorithm to perform the same task automatically.

“Based on the feature-set that our human raters identified, we are now developing an AI and machine-vision algorithm, with preliminary results that indicate the same accuracy as the raters,” said study author Aurélien Bourquard, PhD, of MIT.

The researchers have applied for patents on the technology and launched a company called Leuko, which is working on commercializing the technology with help from MIT.

To move the technology further toward commercialization, the researchers are building a new automated prototype.

“Automating the measurement process is key to making a viable home-use device,” said study author Ian Butterworth, of MIT. “The imaging needs to take place in the right spot on the patient’s finger, and the operation of the device must be straightforward.”

Using this new prototype, the researchers plan to test the device with additional cancer patients. And the team is investigating whether they can get accurate results with shorter lengths of video.

They also plan to adapt the technology so it can generate more precise WBC counts, which would make it useful for monitoring bone marrow transplant recipients or people with certain infectious diseases, Dr Castro-Gonzalez said.

This could also make it possible to determine whether chemotherapy patients can receive their next dose sooner than usual.

“There is a balancing act that oncologists must do,” said study author Alvaro Sanchez-Ferro, MD, of Centro Integral en Neurociencias A.C. HM CINAC in Madrid, Spain.

“Normally, doctors want to make chemotherapy as intensive as possible but without getting people too immunosuppressed. Current 21-day cycles are based on statistics of what most patients can take, but if you are ready early, then they can potentially bring you back early, and that can translate into better survival.”

A portable device could be used to monitor patients’ white blood cell (WBC) levels at home, without the need for blood samples, according to researchers.

The team created a prototype that records video of blood cells flowing through capillaries just below the skin surface at the base of the fingernail.

The group is developing a computer algorithm that, in early testing, has been able to analyze the videos and determine if WBC levels are too low.

The researchers believe this type of device could be used to prevent infections among chemotherapy recipients.

“Our vision is that patients will have this portable device that they can take home, and they can monitor daily how they are reacting to the treatment,” said Carlos Castro-Gonzalez, PhD, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“If they go below the [safe WBC] threshold, then preventive treatment can be deployed.”

Dr Castro-Gonzalez and his colleagues described their prototype, and the testing of it, in Scientific Reports.

The device consists of a wide-field microscope that emits blue light, which penetrates about 50 to 150 microns below the skin and is reflected back to a video camera.

The researchers decided to image the skin at the base of the nail because the capillaries there are very close to the skin surface. These capillaries are so narrow that WBCs must squeeze through one at a time, making them easier to see.

The researchers tested the device in 11 patients at various points during their chemotherapy treatment.

The device does not provide precise WBC counts but allowed the team to differentiate cases of severe neutropenia (<500 neutrophils per μL) from non-neutropenic cases (>1500 neutrophils per μL).

To obtain enough data to make these classifications, the researchers recorded 1 minute of video per patient. Three blinded human assistants then watched the videos and noted whenever a WBC passed by.

However, since submitting their paper, the researchers have been developing a computer algorithm to perform the same task automatically.

“Based on the feature-set that our human raters identified, we are now developing an AI and machine-vision algorithm, with preliminary results that indicate the same accuracy as the raters,” said study author Aurélien Bourquard, PhD, of MIT.

The researchers have applied for patents on the technology and launched a company called Leuko, which is working on commercializing the technology with help from MIT.

To move the technology further toward commercialization, the researchers are building a new automated prototype.

“Automating the measurement process is key to making a viable home-use device,” said study author Ian Butterworth, of MIT. “The imaging needs to take place in the right spot on the patient’s finger, and the operation of the device must be straightforward.”

Using this new prototype, the researchers plan to test the device with additional cancer patients. And the team is investigating whether they can get accurate results with shorter lengths of video.

They also plan to adapt the technology so it can generate more precise WBC counts, which would make it useful for monitoring bone marrow transplant recipients or people with certain infectious diseases, Dr Castro-Gonzalez said.

This could also make it possible to determine whether chemotherapy patients can receive their next dose sooner than usual.

“There is a balancing act that oncologists must do,” said study author Alvaro Sanchez-Ferro, MD, of Centro Integral en Neurociencias A.C. HM CINAC in Madrid, Spain.

“Normally, doctors want to make chemotherapy as intensive as possible but without getting people too immunosuppressed. Current 21-day cycles are based on statistics of what most patients can take, but if you are ready early, then they can potentially bring you back early, and that can translate into better survival.”