User login

Estrogen therapy is highly effective in the treatment of hot flashes among postmenopausal women. For postmenopausal women with a uterus, estrogen treatment for hot flashes is almost always combined with a progestin to reduce the risk of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. For instance, in the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions Trial, 62% of the women with a uterus treated with conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg daily without a progestin developed endometrial hyperplasia.1

In the United States, the most commonly prescribed progestin for hormone therapy has been medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; Provera). However, data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trials indicate that MPA, when combined with CEE, may have adverse health effects among postmenopausal women.

Let’s examine the WHI data

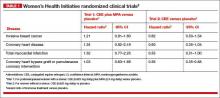

Among women 50 to 59 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a trend toward an increased risk of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction.2 In contrast, among women 50 to 59 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of invasive breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction (TABLE 1).

Among women 50 to 79 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a significantly increased risk of breast cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 1.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–1.53; P = .04).2 In contrast, among women 50 to 79 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of breast cancer (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.61–1.02, P = .07).2

Related article: In the latest report from the WHI, the data contradict the conclusions. Holly Thacker, MD (Commentary; March 2014)

When the analysis was limited to women consistently adherent to their CEE monotherapy, the estrogen treatment significantly decreased the risk of invasive breast cancer (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47–0.97; P = .03).3

The addition of MPA to CEE appears to reverse some of the health benefits of CEE monotherapy, although the biological mechanisms are unclear. This observation should prompt us to explore alternative and novel treatments of vasomotor symptoms that do not utilize MPA. Some options for MPA-free hormone therapy include:

- transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone

- CEE plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system

- bazedoxifene plus CEE.

In addition, nonhormonal treatment of hot flashes is an option, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Related article: Is one oral estrogen formulation safer than another for menopausal women? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Examining the Evidence; January 2014)

MPA-free hormone therapy for hot flashes

Estrogen plus micronized progesterone

When using an estrogen plus progestin regimen to treat hot flashes, many experts favor a combination of low-dose transdermal estradiol and oral micronized progesterone (Prometrium). This combination is believed by some experts to result in a lower risk of venous thromboembolism, stroke, cardiovascular disease, and breast cancer than an estrogen-MPA combination.4–7

When prescribing transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone for a woman within 1 to 2 years of her last menses, a cyclic regimen can help reduce episodes of irregular, unscheduled uterine bleeding. I often use this cyclic regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus cyclic oral micronized progesterone 200 mg prior to bedtime for calendar days 1 to 12.

When using transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone in a woman more than 2 years from her last menses, a continuous regimen is often prescribed. I often use this continuous regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus continuous oral micronized progesterone 100 mg daily prior to bedtime.

Related article: When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Cases in Menopause; February 2014)

Estrogen plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systemThe levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; 20 µg daily; Mirena) is frequently used in Europe to protect the endometrium against the adverse effects of estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women. In a meta-analysis of five clinical trials involving postmenopausal women, the LNG-IUS provided excellent protection against endometrial hyperplasia, compared with MPA.8

One caution about using the LNG-IUS system with estrogen in postmenopausal women is that an observational study of all women with breast cancer in Finland from 1995 through 2007 reported a significantly increased risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women using an LNG-IUS compared with women who did not use hormones or used only estrogen because they had a hysterectomy (TABLE 2).9 This study was not a randomized clinical trial and patients at higher baseline risk for breast cancer, including women with a high body mass index, may have been preferentially treated with an LNG-IUS. More information is needed to better understand the relationship between the LNG-IUS and breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

Related article: What we’ve learned from 2 decades’ experience with the LNG-IUS. Q&A with Oskari Heikinheimo, MD, PhD (February 2011)

Progestin-free hormone treatment, bazedoxifene plus CEE

The main reason for adding a progestin to estrogen therapy for vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women with a uterus is to prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. A major innovation in hormone therapy is the discovery that third-generation selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), such as bazedoxifene (BZA), can prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer but do not interfere with the efficacy of estrogen in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms.

BZA is an estrogen agonist in bone and an estrogen antagonist in the endometrium.10–12 The combination of BZA (20 mg daily) plus CEE (0.45 mg daily) (Duavee) is approved for the treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis.13–15 Over 24 months of therapy, various doses of BZA plus CEE reduced reported daily hot flashes by 52% to 86%.16 In the same study, placebo treatment was associated with a 17% reduction in hot flashes.16

The main adverse effect of BZA/CEE is an increased risk of deep venous thrombosis. Therefore, BZA/CEE is contraindicated in women with a known thrombophilia or a personal history of hormone-induced deep venous thrombosis. The effect of BZA/CEE on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer is not known; over 52 weeks of therapy it did not increase breast density on mammogram.17,18

BZA/CEE is a remarkable advance in hormone therapy. It is progestin-free, uses estrogen to treat vasomotor symptoms, and uses BZA to protect the endometrium against estrogen-induced hyperplasia.

Related article: New option for treating menopausal vasomotor symptoms receives FDA approval. (News for your Practice; October 2013)

Nonhormone treatment of vasomotor symptoms Paroxetine mesylateFor postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms who cannot take estrogen, SSRIs are modestly effective in reducing moderate to severe hot flashes. The US Food and Drug Administration recently approved paroxetine mesylate (Brisdelle) for the treatment of postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms. The approved dose is 7.5 mg daily taken at bedtime.

Data supporting the efficacy of paroxetine mesylate are available from two studies involving 1,184 menopausal women with vasomotor symptoms randomly assigned to receive paroxetine 7.5 mg daily or placebo for 12 weeks of treatment.19-22 In one of the two clinical trials, women treated with paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg daily had 5.6 fewer moderate to severe hot flashes daily after 12 weeks of treatment compared with 3.9 fewer hot flashes with placebo (median treatment difference, 1.7; P<.001).21

Paroxetine can block the metabolism of tamoxifen to its highly potent metabolite, endoxifen. Consequently, paroxetine may reduce the effectiveness of tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer and should be used with caution in postmenopausal women with breast cancer being treated with tamoxifen.

Related article: Paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg found to be a safe alternative to hormone therapy for menopausal women with hot flashes. (News for your Practice; June 2014)

Escitalopram

Gynecologists are familiar with the use of venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, clonidine, citalopram, sertraline, and fluoxetine for the treatment of postmenopausal hot flashes. Recently, escitalopram (Lexapro) at doses of 10 to 20 mg daily has been shown to be more effective than placebo in the treatment of hot flashes and sleep disturbances in postmenopausal women.23,24 In one trial of escitalopram 10 to 20 mg daily versus placebo in 205 postmenopausal women averaging 9.8 hot flashes daily at baseline, escitalopram and placebo reduced mean daily hot flashes by 4.6 and 3.2, respectively (P<.001), after 8 weeks of treatment.

In a meta-analysis of SSRIs for the treatment of hot flashes, data from a mixed-treatment comparison analysis indicated that the rank order from most to least effective therapy for hot flashes was: escitalopram > paroxetine > sertraline > citalopram > fluoxetine.25 Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine, two serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors that are effective in the treatment of hot flashes, were not included in the mixed-treatment comparison.

Use of alternatives to MPA could mean fewer health risks for women on a wide scale

Substantial data indicate that MPA is not an optimal progestin to combine with estrogen for hormone therapy. Currently, many health insurance plans and Medicare use pharmacy management formularies that prioritize dispensing MPA for postmenopausal hormone therapy. Dispensing an alternative to MPA, such as micronized progesterone, often requires the patient to make a significant copayment.

Hopefully, health insurance companies, Medicare, and their affiliated pharmacy management administrators will soon stop their current policy of using financial incentives to favor dispensing MPA when hormone therapy is prescribed because alternatives to MPA appear to be associated with fewer health risks for postmenopausal women.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

1. The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on endometrial histology in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial. JAMA. 1996;275(5):370–375.

2. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefnick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353–1368.

3. Stefanick ML, Anderson GL, Margolis KL, et al; WHI Investigators. Effects of conjugated equine estrogens on breast cancer and mammography screening in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy. JAMA. 2006;295(14):1647–1657.

4. Simon JA. What if the Women’s Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead? [published online head of print January 6, 2014]. Menopause. PMID: 24398406.

5. Manson JE. Current recommendations: What is the clinician to do? Fertil Steril. 2014;101(4):916–921.

6. Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: Results from the E3N cohort study [published correction appears in Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(2):307–308]. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(1):103–111.

7. Renoux C, Dell’aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: A nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519.

8. Somboonpom W, Panna S, Temtanakitpaisan T, Kaewrudee S, Soontrapa S. Effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system plus estrogen therapy in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1060–1066.

9. Lyytinen HK, Dyba T, Ylikorkala O, Pukkala EI. A case-control study on hormone therapy as a risk factor for breast cancer in Finland: Intrauterine system carries a risk as well. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(2):483–489.

10. Komm BS, Mirkin S. An overview of current and emerging SERMs. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;143C:207–222.

11. Ethun KF, Wood CE, Cline JM, Register TC, Appt SE, Clarkson TB. Endometrial profile of bazedoxifene acetate alone and in combination with conjugated equine estrogens in a primate model. Menopause. 2013;20(7):777–784.

12. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone: A randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

13. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15(5):411–418.

14. Pinkerton JV, Abraham L, Bushmakin AG, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for secondary outcomes including vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women by years since menopause in the Selective estrogens, Menopause and Response to Therapy (SMART) trials. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(1):18–28.

15. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

16. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

17. Harvey JA, Holm MK, Ranganath R, Guse PA, Trott EA, Helzner E. The effects of bazedoxifene on mammographic breast density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Menopause. 2009;16(6):1193–1196.

18. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, Shi H, Chines AA, Mirkin S. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20(2):138–145.

19. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: Two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20(10):1027–1035.

20. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Safety profile of paroxetine 7.5 mg in women with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):132S–133S.

21. Orleans RJ, Li L, Kim MJ, et al. FDA approval of paroxetine for menopausal hot flashes. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(19):1777–1779.

22. Paroxetine (Brisdelle) for hot flashes. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2013;55(1428):85–86.

23. Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in health menopausal women. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(3):267–274.

24. Ensrud KE, Joffe H, Guthrie KA, et al. Effect of escitalopram on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes: A randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2012;19(8):848–855.

25. Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1):204–213.

Estrogen therapy is highly effective in the treatment of hot flashes among postmenopausal women. For postmenopausal women with a uterus, estrogen treatment for hot flashes is almost always combined with a progestin to reduce the risk of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. For instance, in the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions Trial, 62% of the women with a uterus treated with conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg daily without a progestin developed endometrial hyperplasia.1

In the United States, the most commonly prescribed progestin for hormone therapy has been medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; Provera). However, data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trials indicate that MPA, when combined with CEE, may have adverse health effects among postmenopausal women.

Let’s examine the WHI data

Among women 50 to 59 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a trend toward an increased risk of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction.2 In contrast, among women 50 to 59 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of invasive breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction (TABLE 1).

Among women 50 to 79 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a significantly increased risk of breast cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 1.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–1.53; P = .04).2 In contrast, among women 50 to 79 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of breast cancer (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.61–1.02, P = .07).2

Related article: In the latest report from the WHI, the data contradict the conclusions. Holly Thacker, MD (Commentary; March 2014)

When the analysis was limited to women consistently adherent to their CEE monotherapy, the estrogen treatment significantly decreased the risk of invasive breast cancer (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47–0.97; P = .03).3

The addition of MPA to CEE appears to reverse some of the health benefits of CEE monotherapy, although the biological mechanisms are unclear. This observation should prompt us to explore alternative and novel treatments of vasomotor symptoms that do not utilize MPA. Some options for MPA-free hormone therapy include:

- transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone

- CEE plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system

- bazedoxifene plus CEE.

In addition, nonhormonal treatment of hot flashes is an option, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Related article: Is one oral estrogen formulation safer than another for menopausal women? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Examining the Evidence; January 2014)

MPA-free hormone therapy for hot flashes

Estrogen plus micronized progesterone

When using an estrogen plus progestin regimen to treat hot flashes, many experts favor a combination of low-dose transdermal estradiol and oral micronized progesterone (Prometrium). This combination is believed by some experts to result in a lower risk of venous thromboembolism, stroke, cardiovascular disease, and breast cancer than an estrogen-MPA combination.4–7

When prescribing transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone for a woman within 1 to 2 years of her last menses, a cyclic regimen can help reduce episodes of irregular, unscheduled uterine bleeding. I often use this cyclic regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus cyclic oral micronized progesterone 200 mg prior to bedtime for calendar days 1 to 12.

When using transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone in a woman more than 2 years from her last menses, a continuous regimen is often prescribed. I often use this continuous regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus continuous oral micronized progesterone 100 mg daily prior to bedtime.

Related article: When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Cases in Menopause; February 2014)

Estrogen plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systemThe levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; 20 µg daily; Mirena) is frequently used in Europe to protect the endometrium against the adverse effects of estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women. In a meta-analysis of five clinical trials involving postmenopausal women, the LNG-IUS provided excellent protection against endometrial hyperplasia, compared with MPA.8

One caution about using the LNG-IUS system with estrogen in postmenopausal women is that an observational study of all women with breast cancer in Finland from 1995 through 2007 reported a significantly increased risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women using an LNG-IUS compared with women who did not use hormones or used only estrogen because they had a hysterectomy (TABLE 2).9 This study was not a randomized clinical trial and patients at higher baseline risk for breast cancer, including women with a high body mass index, may have been preferentially treated with an LNG-IUS. More information is needed to better understand the relationship between the LNG-IUS and breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

Related article: What we’ve learned from 2 decades’ experience with the LNG-IUS. Q&A with Oskari Heikinheimo, MD, PhD (February 2011)

Progestin-free hormone treatment, bazedoxifene plus CEE

The main reason for adding a progestin to estrogen therapy for vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women with a uterus is to prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. A major innovation in hormone therapy is the discovery that third-generation selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), such as bazedoxifene (BZA), can prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer but do not interfere with the efficacy of estrogen in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms.

BZA is an estrogen agonist in bone and an estrogen antagonist in the endometrium.10–12 The combination of BZA (20 mg daily) plus CEE (0.45 mg daily) (Duavee) is approved for the treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis.13–15 Over 24 months of therapy, various doses of BZA plus CEE reduced reported daily hot flashes by 52% to 86%.16 In the same study, placebo treatment was associated with a 17% reduction in hot flashes.16

The main adverse effect of BZA/CEE is an increased risk of deep venous thrombosis. Therefore, BZA/CEE is contraindicated in women with a known thrombophilia or a personal history of hormone-induced deep venous thrombosis. The effect of BZA/CEE on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer is not known; over 52 weeks of therapy it did not increase breast density on mammogram.17,18

BZA/CEE is a remarkable advance in hormone therapy. It is progestin-free, uses estrogen to treat vasomotor symptoms, and uses BZA to protect the endometrium against estrogen-induced hyperplasia.

Related article: New option for treating menopausal vasomotor symptoms receives FDA approval. (News for your Practice; October 2013)

Nonhormone treatment of vasomotor symptoms Paroxetine mesylateFor postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms who cannot take estrogen, SSRIs are modestly effective in reducing moderate to severe hot flashes. The US Food and Drug Administration recently approved paroxetine mesylate (Brisdelle) for the treatment of postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms. The approved dose is 7.5 mg daily taken at bedtime.

Data supporting the efficacy of paroxetine mesylate are available from two studies involving 1,184 menopausal women with vasomotor symptoms randomly assigned to receive paroxetine 7.5 mg daily or placebo for 12 weeks of treatment.19-22 In one of the two clinical trials, women treated with paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg daily had 5.6 fewer moderate to severe hot flashes daily after 12 weeks of treatment compared with 3.9 fewer hot flashes with placebo (median treatment difference, 1.7; P<.001).21

Paroxetine can block the metabolism of tamoxifen to its highly potent metabolite, endoxifen. Consequently, paroxetine may reduce the effectiveness of tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer and should be used with caution in postmenopausal women with breast cancer being treated with tamoxifen.

Related article: Paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg found to be a safe alternative to hormone therapy for menopausal women with hot flashes. (News for your Practice; June 2014)

Escitalopram

Gynecologists are familiar with the use of venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, clonidine, citalopram, sertraline, and fluoxetine for the treatment of postmenopausal hot flashes. Recently, escitalopram (Lexapro) at doses of 10 to 20 mg daily has been shown to be more effective than placebo in the treatment of hot flashes and sleep disturbances in postmenopausal women.23,24 In one trial of escitalopram 10 to 20 mg daily versus placebo in 205 postmenopausal women averaging 9.8 hot flashes daily at baseline, escitalopram and placebo reduced mean daily hot flashes by 4.6 and 3.2, respectively (P<.001), after 8 weeks of treatment.

In a meta-analysis of SSRIs for the treatment of hot flashes, data from a mixed-treatment comparison analysis indicated that the rank order from most to least effective therapy for hot flashes was: escitalopram > paroxetine > sertraline > citalopram > fluoxetine.25 Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine, two serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors that are effective in the treatment of hot flashes, were not included in the mixed-treatment comparison.

Use of alternatives to MPA could mean fewer health risks for women on a wide scale

Substantial data indicate that MPA is not an optimal progestin to combine with estrogen for hormone therapy. Currently, many health insurance plans and Medicare use pharmacy management formularies that prioritize dispensing MPA for postmenopausal hormone therapy. Dispensing an alternative to MPA, such as micronized progesterone, often requires the patient to make a significant copayment.

Hopefully, health insurance companies, Medicare, and their affiliated pharmacy management administrators will soon stop their current policy of using financial incentives to favor dispensing MPA when hormone therapy is prescribed because alternatives to MPA appear to be associated with fewer health risks for postmenopausal women.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

Estrogen therapy is highly effective in the treatment of hot flashes among postmenopausal women. For postmenopausal women with a uterus, estrogen treatment for hot flashes is almost always combined with a progestin to reduce the risk of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. For instance, in the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions Trial, 62% of the women with a uterus treated with conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) 0.625 mg daily without a progestin developed endometrial hyperplasia.1

In the United States, the most commonly prescribed progestin for hormone therapy has been medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA; Provera). However, data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trials indicate that MPA, when combined with CEE, may have adverse health effects among postmenopausal women.

Let’s examine the WHI data

Among women 50 to 59 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a trend toward an increased risk of breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction.2 In contrast, among women 50 to 59 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of invasive breast cancer, coronary heart disease, and myocardial infarction (TABLE 1).

Among women 50 to 79 years of age with a uterus, the combination of CEE plus MPA was associated with a significantly increased risk of breast cancer (hazard ratio [HR], 1.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01–1.53; P = .04).2 In contrast, among women 50 to 79 years of age without a uterus, CEE monotherapy was associated with a trend toward a decreased risk of breast cancer (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.61–1.02, P = .07).2

Related article: In the latest report from the WHI, the data contradict the conclusions. Holly Thacker, MD (Commentary; March 2014)

When the analysis was limited to women consistently adherent to their CEE monotherapy, the estrogen treatment significantly decreased the risk of invasive breast cancer (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.47–0.97; P = .03).3

The addition of MPA to CEE appears to reverse some of the health benefits of CEE monotherapy, although the biological mechanisms are unclear. This observation should prompt us to explore alternative and novel treatments of vasomotor symptoms that do not utilize MPA. Some options for MPA-free hormone therapy include:

- transdermal estradiol plus micronized progesterone

- CEE plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system

- bazedoxifene plus CEE.

In addition, nonhormonal treatment of hot flashes is an option, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Related article: Is one oral estrogen formulation safer than another for menopausal women? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Examining the Evidence; January 2014)

MPA-free hormone therapy for hot flashes

Estrogen plus micronized progesterone

When using an estrogen plus progestin regimen to treat hot flashes, many experts favor a combination of low-dose transdermal estradiol and oral micronized progesterone (Prometrium). This combination is believed by some experts to result in a lower risk of venous thromboembolism, stroke, cardiovascular disease, and breast cancer than an estrogen-MPA combination.4–7

When prescribing transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone for a woman within 1 to 2 years of her last menses, a cyclic regimen can help reduce episodes of irregular, unscheduled uterine bleeding. I often use this cyclic regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus cyclic oral micronized progesterone 200 mg prior to bedtime for calendar days 1 to 12.

When using transdermal estradiol plus oral micronized progesterone in a woman more than 2 years from her last menses, a continuous regimen is often prescribed. I often use this continuous regimen: transdermal estradiol 0.0375 mg plus continuous oral micronized progesterone 100 mg daily prior to bedtime.

Related article: When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Cases in Menopause; February 2014)

Estrogen plus a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systemThe levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; 20 µg daily; Mirena) is frequently used in Europe to protect the endometrium against the adverse effects of estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women. In a meta-analysis of five clinical trials involving postmenopausal women, the LNG-IUS provided excellent protection against endometrial hyperplasia, compared with MPA.8

One caution about using the LNG-IUS system with estrogen in postmenopausal women is that an observational study of all women with breast cancer in Finland from 1995 through 2007 reported a significantly increased risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women using an LNG-IUS compared with women who did not use hormones or used only estrogen because they had a hysterectomy (TABLE 2).9 This study was not a randomized clinical trial and patients at higher baseline risk for breast cancer, including women with a high body mass index, may have been preferentially treated with an LNG-IUS. More information is needed to better understand the relationship between the LNG-IUS and breast cancer in postmenopausal women.

Related article: What we’ve learned from 2 decades’ experience with the LNG-IUS. Q&A with Oskari Heikinheimo, MD, PhD (February 2011)

Progestin-free hormone treatment, bazedoxifene plus CEE

The main reason for adding a progestin to estrogen therapy for vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women with a uterus is to prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer. A major innovation in hormone therapy is the discovery that third-generation selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), such as bazedoxifene (BZA), can prevent estrogen-induced development of endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer but do not interfere with the efficacy of estrogen in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms.

BZA is an estrogen agonist in bone and an estrogen antagonist in the endometrium.10–12 The combination of BZA (20 mg daily) plus CEE (0.45 mg daily) (Duavee) is approved for the treatment of moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms and prevention of osteoporosis.13–15 Over 24 months of therapy, various doses of BZA plus CEE reduced reported daily hot flashes by 52% to 86%.16 In the same study, placebo treatment was associated with a 17% reduction in hot flashes.16

The main adverse effect of BZA/CEE is an increased risk of deep venous thrombosis. Therefore, BZA/CEE is contraindicated in women with a known thrombophilia or a personal history of hormone-induced deep venous thrombosis. The effect of BZA/CEE on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer is not known; over 52 weeks of therapy it did not increase breast density on mammogram.17,18

BZA/CEE is a remarkable advance in hormone therapy. It is progestin-free, uses estrogen to treat vasomotor symptoms, and uses BZA to protect the endometrium against estrogen-induced hyperplasia.

Related article: New option for treating menopausal vasomotor symptoms receives FDA approval. (News for your Practice; October 2013)

Nonhormone treatment of vasomotor symptoms Paroxetine mesylateFor postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms who cannot take estrogen, SSRIs are modestly effective in reducing moderate to severe hot flashes. The US Food and Drug Administration recently approved paroxetine mesylate (Brisdelle) for the treatment of postmenopausal vasomotor symptoms. The approved dose is 7.5 mg daily taken at bedtime.

Data supporting the efficacy of paroxetine mesylate are available from two studies involving 1,184 menopausal women with vasomotor symptoms randomly assigned to receive paroxetine 7.5 mg daily or placebo for 12 weeks of treatment.19-22 In one of the two clinical trials, women treated with paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg daily had 5.6 fewer moderate to severe hot flashes daily after 12 weeks of treatment compared with 3.9 fewer hot flashes with placebo (median treatment difference, 1.7; P<.001).21

Paroxetine can block the metabolism of tamoxifen to its highly potent metabolite, endoxifen. Consequently, paroxetine may reduce the effectiveness of tamoxifen treatment for breast cancer and should be used with caution in postmenopausal women with breast cancer being treated with tamoxifen.

Related article: Paroxetine mesylate 7.5 mg found to be a safe alternative to hormone therapy for menopausal women with hot flashes. (News for your Practice; June 2014)

Escitalopram

Gynecologists are familiar with the use of venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, clonidine, citalopram, sertraline, and fluoxetine for the treatment of postmenopausal hot flashes. Recently, escitalopram (Lexapro) at doses of 10 to 20 mg daily has been shown to be more effective than placebo in the treatment of hot flashes and sleep disturbances in postmenopausal women.23,24 In one trial of escitalopram 10 to 20 mg daily versus placebo in 205 postmenopausal women averaging 9.8 hot flashes daily at baseline, escitalopram and placebo reduced mean daily hot flashes by 4.6 and 3.2, respectively (P<.001), after 8 weeks of treatment.

In a meta-analysis of SSRIs for the treatment of hot flashes, data from a mixed-treatment comparison analysis indicated that the rank order from most to least effective therapy for hot flashes was: escitalopram > paroxetine > sertraline > citalopram > fluoxetine.25 Venlafaxine and desvenlafaxine, two serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors that are effective in the treatment of hot flashes, were not included in the mixed-treatment comparison.

Use of alternatives to MPA could mean fewer health risks for women on a wide scale

Substantial data indicate that MPA is not an optimal progestin to combine with estrogen for hormone therapy. Currently, many health insurance plans and Medicare use pharmacy management formularies that prioritize dispensing MPA for postmenopausal hormone therapy. Dispensing an alternative to MPA, such as micronized progesterone, often requires the patient to make a significant copayment.

Hopefully, health insurance companies, Medicare, and their affiliated pharmacy management administrators will soon stop their current policy of using financial incentives to favor dispensing MPA when hormone therapy is prescribed because alternatives to MPA appear to be associated with fewer health risks for postmenopausal women.

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU! Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor to: [email protected]

1. The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on endometrial histology in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial. JAMA. 1996;275(5):370–375.

2. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefnick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353–1368.

3. Stefanick ML, Anderson GL, Margolis KL, et al; WHI Investigators. Effects of conjugated equine estrogens on breast cancer and mammography screening in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy. JAMA. 2006;295(14):1647–1657.

4. Simon JA. What if the Women’s Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead? [published online head of print January 6, 2014]. Menopause. PMID: 24398406.

5. Manson JE. Current recommendations: What is the clinician to do? Fertil Steril. 2014;101(4):916–921.

6. Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: Results from the E3N cohort study [published correction appears in Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(2):307–308]. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(1):103–111.

7. Renoux C, Dell’aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: A nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519.

8. Somboonpom W, Panna S, Temtanakitpaisan T, Kaewrudee S, Soontrapa S. Effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system plus estrogen therapy in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1060–1066.

9. Lyytinen HK, Dyba T, Ylikorkala O, Pukkala EI. A case-control study on hormone therapy as a risk factor for breast cancer in Finland: Intrauterine system carries a risk as well. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(2):483–489.

10. Komm BS, Mirkin S. An overview of current and emerging SERMs. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;143C:207–222.

11. Ethun KF, Wood CE, Cline JM, Register TC, Appt SE, Clarkson TB. Endometrial profile of bazedoxifene acetate alone and in combination with conjugated equine estrogens in a primate model. Menopause. 2013;20(7):777–784.

12. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone: A randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

13. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15(5):411–418.

14. Pinkerton JV, Abraham L, Bushmakin AG, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for secondary outcomes including vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women by years since menopause in the Selective estrogens, Menopause and Response to Therapy (SMART) trials. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(1):18–28.

15. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

16. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

17. Harvey JA, Holm MK, Ranganath R, Guse PA, Trott EA, Helzner E. The effects of bazedoxifene on mammographic breast density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Menopause. 2009;16(6):1193–1196.

18. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, Shi H, Chines AA, Mirkin S. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20(2):138–145.

19. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: Two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20(10):1027–1035.

20. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Safety profile of paroxetine 7.5 mg in women with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):132S–133S.

21. Orleans RJ, Li L, Kim MJ, et al. FDA approval of paroxetine for menopausal hot flashes. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(19):1777–1779.

22. Paroxetine (Brisdelle) for hot flashes. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2013;55(1428):85–86.

23. Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in health menopausal women. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(3):267–274.

24. Ensrud KE, Joffe H, Guthrie KA, et al. Effect of escitalopram on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes: A randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2012;19(8):848–855.

25. Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1):204–213.

1. The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on endometrial histology in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial. JAMA. 1996;275(5):370–375.

2. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefnick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1353–1368.

3. Stefanick ML, Anderson GL, Margolis KL, et al; WHI Investigators. Effects of conjugated equine estrogens on breast cancer and mammography screening in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy. JAMA. 2006;295(14):1647–1657.

4. Simon JA. What if the Women’s Health Initiative had used transdermal estradiol and oral progesterone instead? [published online head of print January 6, 2014]. Menopause. PMID: 24398406.

5. Manson JE. Current recommendations: What is the clinician to do? Fertil Steril. 2014;101(4):916–921.

6. Fournier A, Berrino F, Clavel-Chapelon F. Unequal risks for breast cancer associated with different hormone replacement therapies: Results from the E3N cohort study [published correction appears in Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(2):307–308]. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(1):103–111.

7. Renoux C, Dell’aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: A nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519.

8. Somboonpom W, Panna S, Temtanakitpaisan T, Kaewrudee S, Soontrapa S. Effects of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system plus estrogen therapy in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1060–1066.

9. Lyytinen HK, Dyba T, Ylikorkala O, Pukkala EI. A case-control study on hormone therapy as a risk factor for breast cancer in Finland: Intrauterine system carries a risk as well. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(2):483–489.

10. Komm BS, Mirkin S. An overview of current and emerging SERMs. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;143C:207–222.

11. Ethun KF, Wood CE, Cline JM, Register TC, Appt SE, Clarkson TB. Endometrial profile of bazedoxifene acetate alone and in combination with conjugated equine estrogens in a primate model. Menopause. 2013;20(7):777–784.

12. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Lindsay R, et al; SMART-5 Investigators. Effects of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens on the endometrium and bone: A randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(2):E189–E198.

13. Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH, Racketa J, Mirkin S. Bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for menopausal symptom treatment and osteoporosis prevention. Climacteric. 2012;15(5):411–418.

14. Pinkerton JV, Abraham L, Bushmakin AG, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for secondary outcomes including vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women by years since menopause in the Selective estrogens, Menopause and Response to Therapy (SMART) trials. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(1):18–28.

15. Pinkerton JV, Harvey JA, Pan K, et al. Breast effects of bazedoxifene-conjugated estrogens: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(5):959–968.

16. Lobo RA, Pinkerton JV, Gass ML, et al. Evaluation of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and effects on metabolic parameters and overall safety profile. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1025–1038.

17. Harvey JA, Holm MK, Ranganath R, Guse PA, Trott EA, Helzner E. The effects of bazedoxifene on mammographic breast density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Menopause. 2009;16(6):1193–1196.

18. Harvey JA, Pinkerton JV, Baracat EC, Shi H, Chines AA, Mirkin S. Breast density changes in a randomized controlled trial evaluating bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens. Menopause. 2013;20(2):138–145.

19. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kaunitz AM, et al. Low-dose paroxetine 7.5 mg for menopausal vasomotor symptoms: Two randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2013;20(10):1027–1035.

20. Simon JA, Portman DJ, Kazempour K, Mekonnen H, Bhaskar S, Lippman J. Safety profile of paroxetine 7.5 mg in women with moderate-to-severe vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(suppl 1):132S–133S.

21. Orleans RJ, Li L, Kim MJ, et al. FDA approval of paroxetine for menopausal hot flashes. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(19):1777–1779.

22. Paroxetine (Brisdelle) for hot flashes. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2013;55(1428):85–86.

23. Freeman EW, Guthrie KA, Caan B, et al. Efficacy of escitalopram for hot flashes in health menopausal women. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305(3):267–274.

24. Ensrud KE, Joffe H, Guthrie KA, et al. Effect of escitalopram on insomnia symptoms and subjective sleep quality in healthy perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with hot flashes: A randomized controlled trial. Menopause. 2012;19(8):848–855.

25. Shams T, Firwana B, Habib F, et al. SSRIs for hot flashes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1):204–213.