User login

THE CASE

Al* is a 48-year-old patient whose wife, Vera, died of complications from chronic illness 14 months ago. Al thinks about Vera constantly and says he still has difficulty accepting that she is gone. He does not leave the house much anymore and continues to set a place for her at the kitchen table on special occasions. He says, “Some nights in bed, I swear I can hear her in the living room.”

How would you proceed with this patient?

* The names of the patient and his spouse have been changed to protect their identities.

After the loss of a loved one, grief is a natural response to the separation and stress that go along with the death. Most people, after suffering a loss, experience distress that varies in intensity and gradually decreases over time. Thus, the grieving individual does not act as they would normally if they were not bereaved. However, gains are generally made month by month, and most people adjust to the grief and adapt their lives after some time dealing with the absence of the loved one.1

There’s grief, and then there’s complicated grief

For about 2% to 4% of the population who have experienced a significant loss, complicated grief is an issue.2 As its hallmark, complicated grief exceeds the typical amount of time (6-12 months) that people need to recover from a loss. Prevalence has been estimated at 10% to 20% among grieving individuals for whom the death being grieved was that of a romantic partner or child.2 At increased risk for this disorder are women older than 60 years, patients diagnosed with depression or substance abuse, individuals under financial strain, and those who have experienced a violent or sudden loss.3

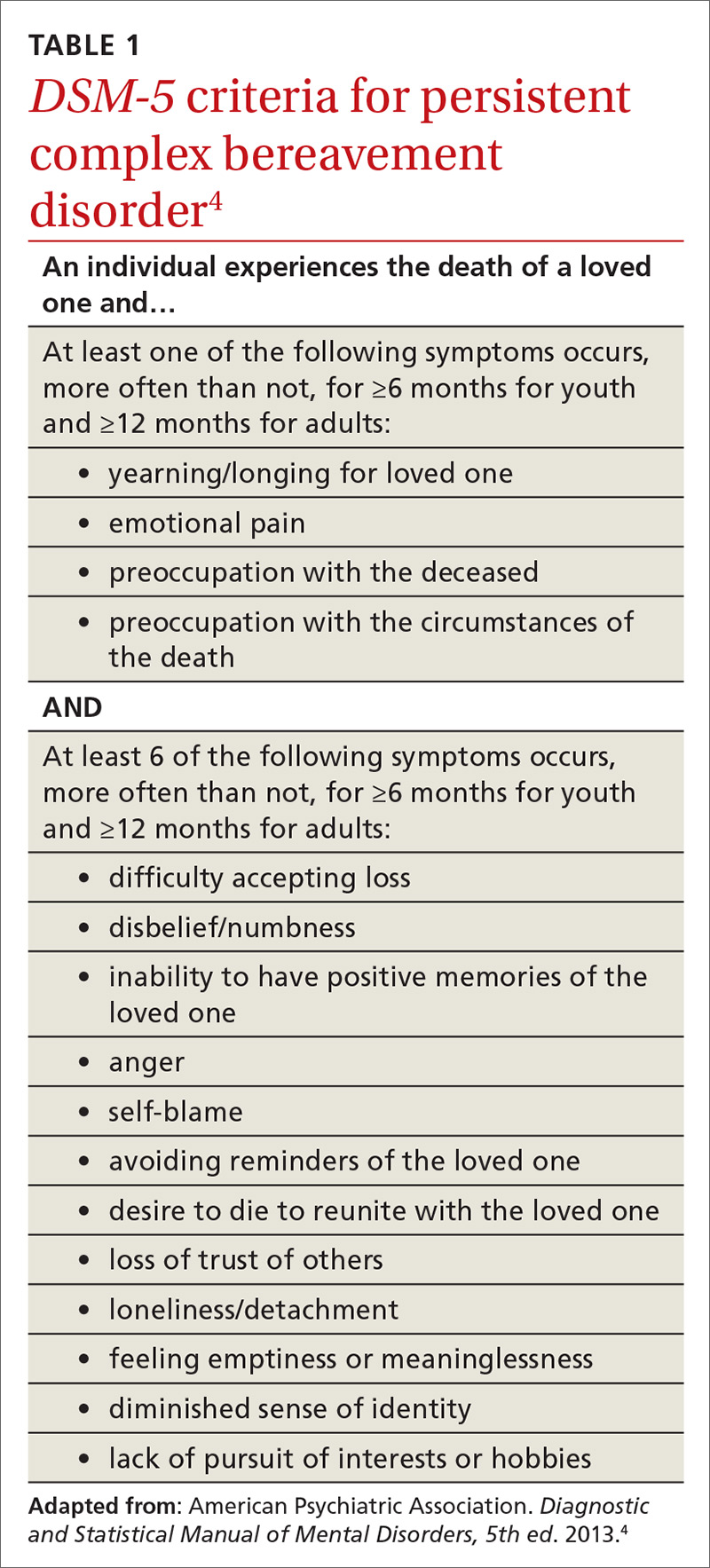

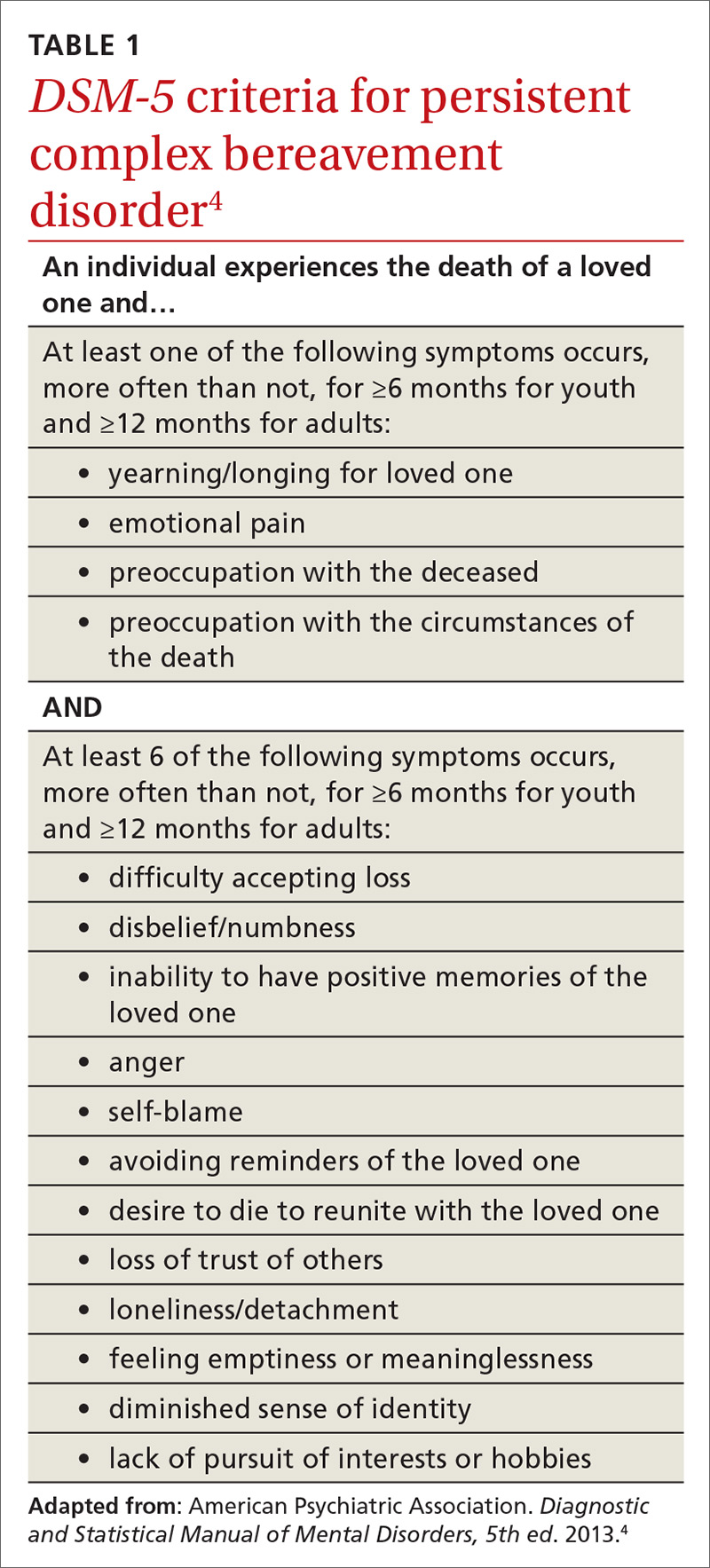

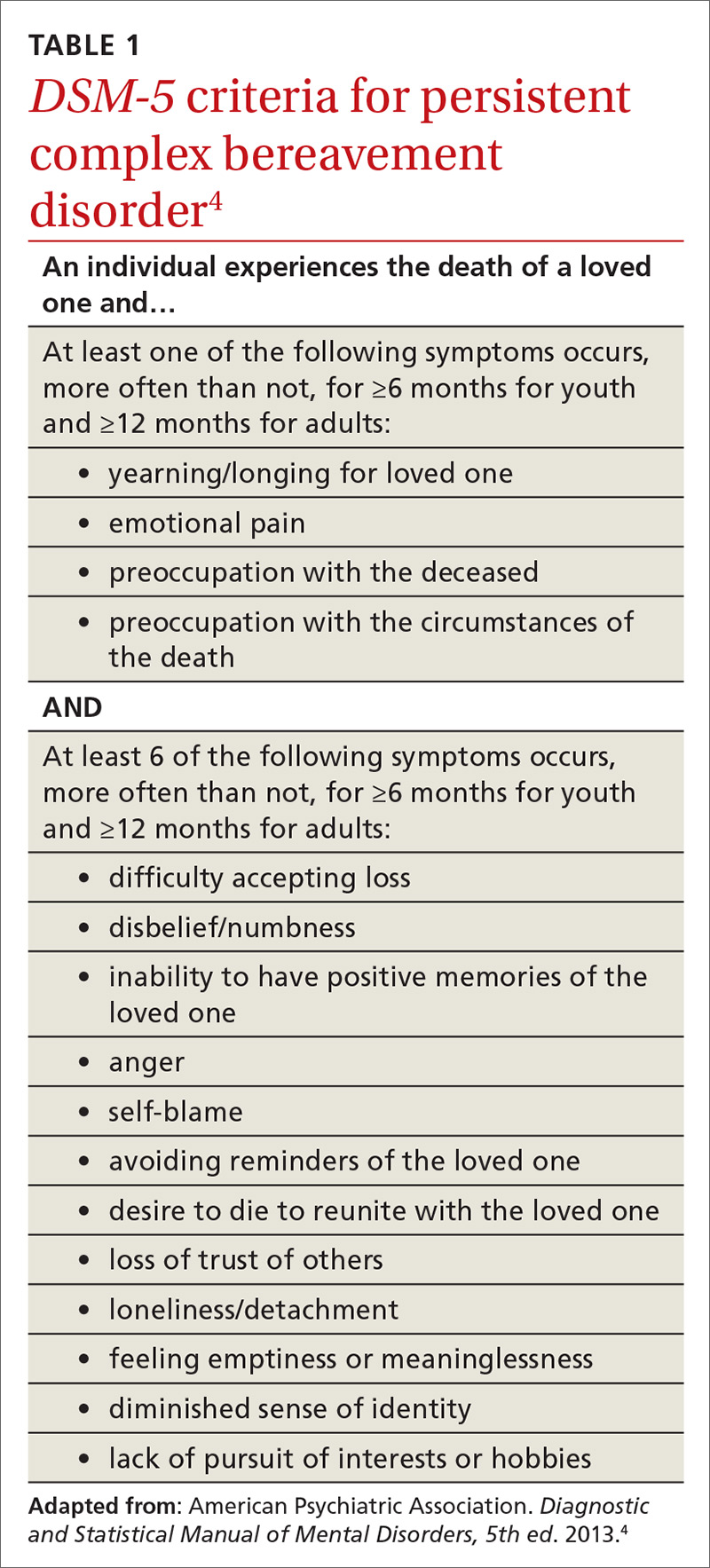

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) has conceptualized complicated grief with the name, persistent complex bereavement disorder (PCBD).4 While the guidelines for the definition are still in progress, several specified symptoms must have been present for at least 6 months to a year or more (TABLE 14). For instance, the patient has been ruminating about the death, has been unable to accept the death, or has felt shocked or numb. They may also experience anger, have difficulty trusting others, and be preoccupied with the deceased (eg, sense they can hear their lost loved one, feel the loved one’s pain for them). Symptoms of PCBD may also include experiencing vivid reminders of the loss and avoiding situations that bring up thoughts about the death.4 (Of note: A grief diagnosis in ICD-10 is captured by the code F43.21; however, there is no specific code for complicated grief or PCBD.)

PCBD is a “condition for further study” in DSM-5; it was omitted from DSM-IV only after much debate. One reason for its omission was concern that clinicians might “pathologize” grief more than it needs to be.5 Grief is regarded as a natural process that might be stymied by a formal diagnosis leading to medical treatment.

Shifting the grief diagnosis paradigm

One new development is that recently bereaved patients can be diagnosed with depression if they meet the criteria for that diagnosis. In the past, someone who met criteria for major depression would be excluded from that diagnosis if the depression ensued from grief. DSM-5 no longer makes that distinction.4 Given this diagnostic shift, one might wonder about the difference between PCBD and depression, particularly if the patient is a grieving individual with a current diagnosis of depression.5

Continue to: Differences between PCBD and major depression

Differences between PCBD and major depression. While antidepressant medication is helpful for patients with moderate-to-severe depression, it has thus far been less helpful for those solely experiencing complicated grief.6 The same holds true for traditional psychotherapy. While family physicians can confidently refer people to psychotherapy for depression, it is not as efficacious as focused therapy designed for those with PCBD.6

Other differences between PCBD and major depression involve the constructs of guilt and yearning. Depressed patients typically feel guilty about a number of things, while those with complicated grief have specific death-focused guilt.7 Depressed people generally do not yearn, while those with grief yearn for their loved one. Finally, and most concerning to clinicians, some patients with PCBD have suicidal thoughts.8 While such thoughts in depression are often linked to hopelessness, suicidal thoughts for grieving individuals are generally driven by a desire to be reunited with the deceased loved one.

While these differences may help in making treatment decisions, there can be overlap between depression and complicated grief. As with many mental health diagnoses, major depression and PCBD are not mutually exclusive.4

The role of hospice. Another factor sometimes associated with complicated grief is any hindrance to the survivor’s ability to communicate or say goodbye to the loved one at the end of life.9 This may be avoided if the loved one is in hospice care and is not subjected to procedures that impair communication (ie, ventilator use, sedation). Medicare requires that certified hospice programs offer bereavement services for 1 year following patient death.10 Some hospice providers even offer bereavement services to those not enrolled in hospice. However, evidence indicates that only about 30% of bereaved caregivers take advantage of hospice bereavement services.11 Family physicians may help patients during this process by providing an early referral to hospice services and recommending bereavement counseling. Referral to hospice care can also facilitate discussions that the patient may need to have with the physician or others regarding spirituality. Hospital chaplains can also be referred or get involved with patients and family upon request.

Assessment focal points and tools

As is the case with most mental health concerns, primary care is at the forefront of early assessment. Evaluation of grief is an ongoing process and is multifactorial. One focus is the intensity of the grief. Is the patient reacting to the loss in a way that is disproportionately severe when compared with others who grieve? Another factor is the time elapsed since the loss. If the loss was more than 6 months ago, the patient should have made some progress. Assess grieving patients at around 6 months post-loss to determine how they are handling grief. As mentioned, DSM-5 has criteria for PCBD that providers can use in determining a patient’s grief status. Also needed are assessments for the other DSM-5 issues often associated with loss: depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Continue to: While no clinical measure is perfect...

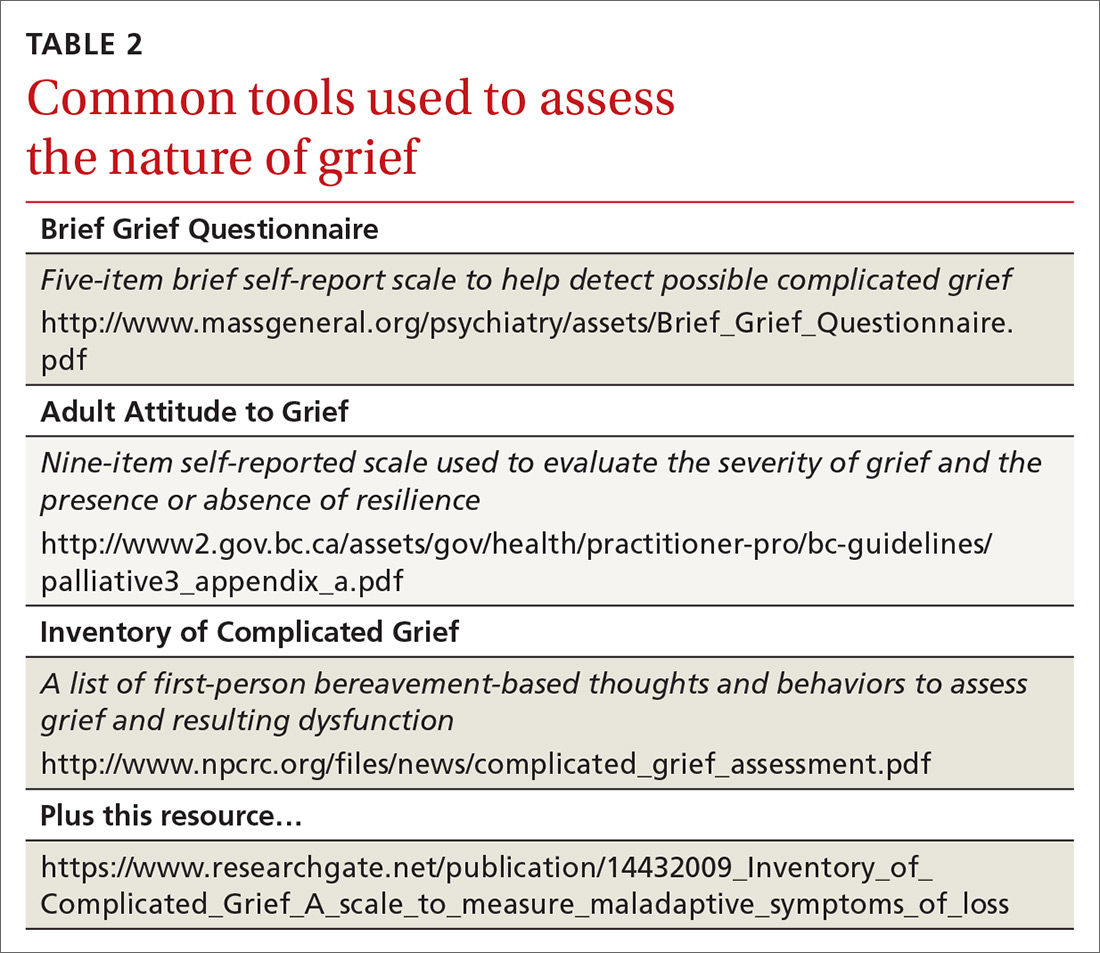

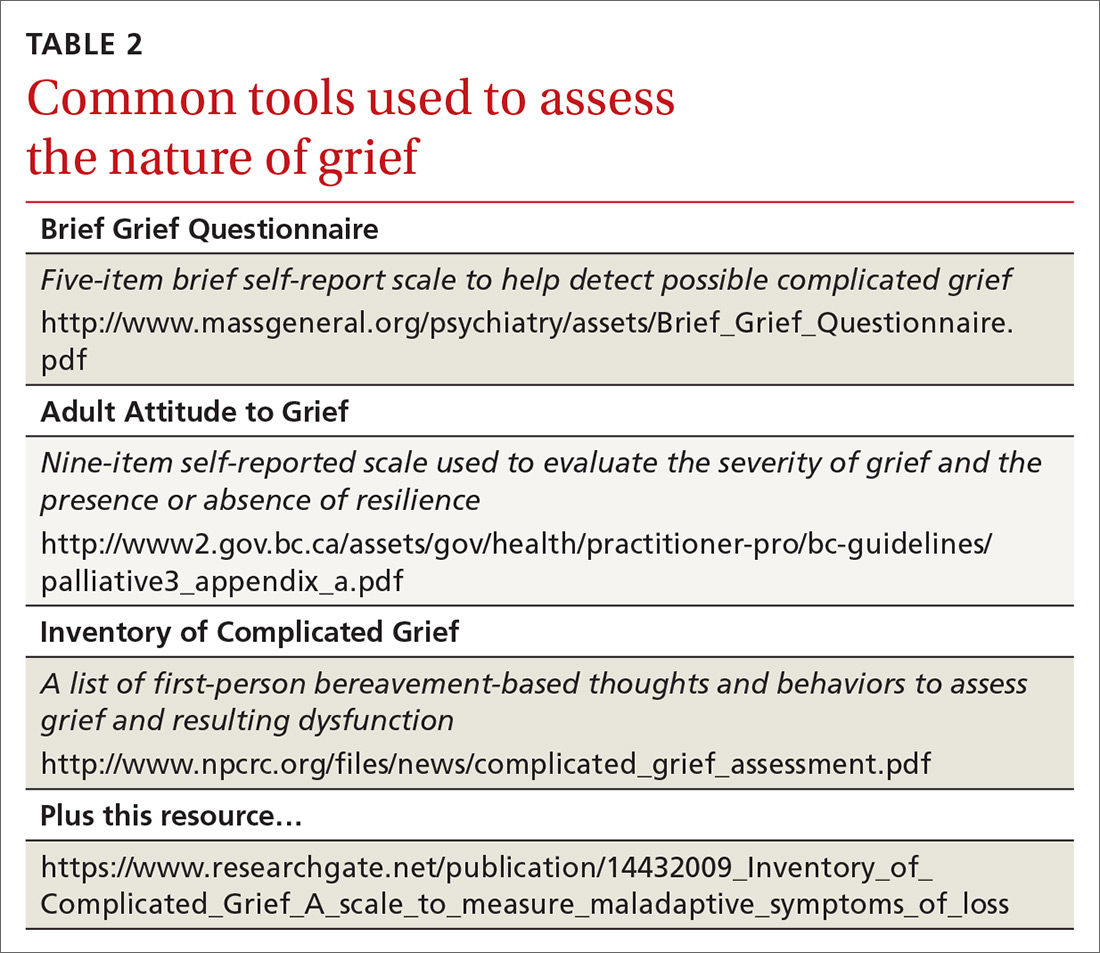

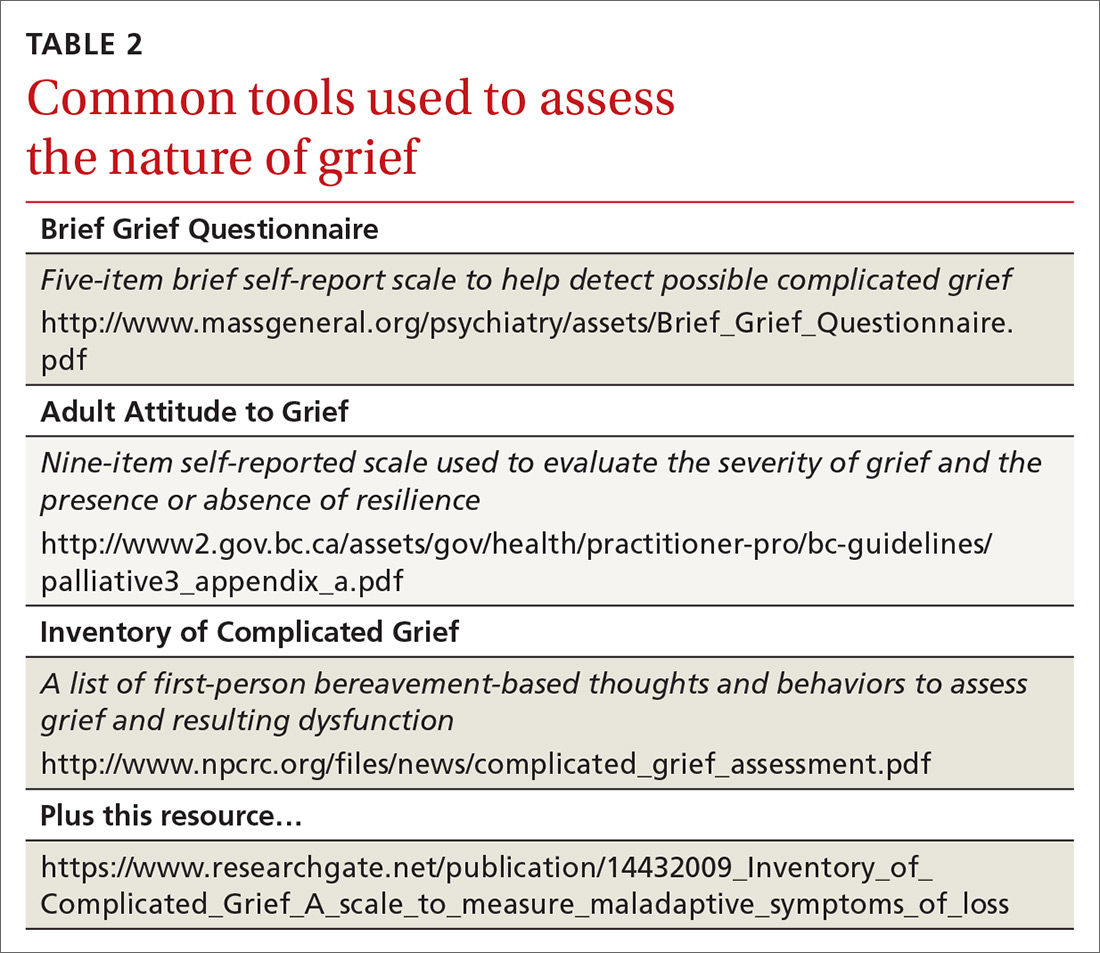

While no clinical measure is perfect, there are tools that can help in assessing patients for the possibility of complicated grief (TABLE 2). Also keep in mind that no measure can make a diagnosis of PCBD, as it is a clinical judgment, not a score on a scale. Furthermore, there is no measure that can accurately predict future complicated grief.6 In most busy practices, the Brief Grief Questionnaire (http://www.massgeneral.org/psychiatry/assets/Brief_Grief_Questionnaire.pdf ) would be the easiest tool to administer, but a case could be made for any of the measures.

Treatment

The literature base emphasizes that PCBD treatment requires a different focus than that applied to uncomplicated grief. And while most people with major depression will respond to medication and psychotherapy, there are provisos to keep in mind when depression is associated with complicated grief.

Complicated grief treatment (CGT) has been studied extensively.6 This treatment combines some of the tenets of evidence-based PTSD treatments, interpersonal therapy for grief, and cognitive behavioral therapy. CGT is generally an individual treatment, although group therapy using some of its tenets can also be effective. According to complicated grief researchers, tasks to accomplish in CGT include establishing a “new normal” following the loss, promoting self-regulation in the grieving, building social connections, and setting aspirational goals for the future.6 Other goals are to revisit the world, tell stories of the past, and relive old memories in a more positive light. Common suggestions in CGT that run parallel to conventional thoughts on dealing with grief include increasing time outside the home, getting more involved interpersonally, and increasing mindfulness-based practices.

A second-line evidence-based treatment for PCBD is the use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).6 Some studies have found benefit from SSRI treatment, although the findings are preliminary and modest.12 One observational study examined patients who had recently experienced loss and were receiving CGT with or without medication. Researchers found that CGT with medication (citalopram) led to a 61% positive response rate while CGT alone led to a 41% response rate.13 Thus, findings revealed some benefit to combining an antidepressant with CGT, indicating that SSRIs may be helpful as an adjunct treatment.

THE CASE

Al was treated for complicated grief by his family physician and a psychologist for approximately a year. He responded well to an SSRI and received psychotherapy that focused on the tenets of CGT. Prior to his last psychotherapy visit, he reported leaving the house regularly to dine at restaurants and meet up with co-workers after hours. He said, “I still miss Vera quite a bit, but I know that I feel better.”

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; [email protected]

1. Cozza SJ, Fisher JE, Mauro C, et al. Performance of DSM-5 persistent complex bereavement disorder criteria in a community sample of bereaved military family members. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:919-929.

2. Kersting A, Brähler E, Glaesmer H, et al. Prevalence of complicated grief in a representative population-based sample. J Affect Disord. 2011;131:339-343.

3. Fujisawa D, Miyashita M, Nakajima S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of complicated grief in general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;127:352-358.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: APA Press; 2013.

5. Shear MK, Simon N, Wall M, et al. Complicated grief and related issues for DSM-5. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:103-117.

6. Shear MK. Clinical Practice. Complicated grief. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:153-160.

7. Wolfelt AD. Counseling Skills for Companioning the Mourner: The Fundamentals of Effective Grief Counseling. Fort Collins, CO: Companion Press; 2016.

8. Szanto K, Shear MK, Houck PR, et al. Indirect self-destructive behavior and overt suicidality in patients with complicated grief. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:233-239.

9. Otani H, Yoshida S, Morita T, et al. Meaningful communication before death, but not present at the time of death itself, is associated with better outcomes on measures of depression and complicated grief among bereaved family members of cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54:273-279.

10. CMS. Medicare benefit policy manual: coverage of hospice services under hospital insurance. www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/bp102c09.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2018.

11. Cherlin E, Barry LC, Prigerson H, et al. Bereavement services for family caregivers: how often used, why, and why not. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:148–158.

12. Bui E, Nidal-Vicens M, Simon NM. Pharmacologic approaches to the treatment of complicated grief: rationale and a brief review of the literature. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012;14:149-157.

13. Shear MK, Reynolds CF 3rd, Simon NM, et al. Optimizing treatment of complicated grief: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:685-694.

THE CASE

Al* is a 48-year-old patient whose wife, Vera, died of complications from chronic illness 14 months ago. Al thinks about Vera constantly and says he still has difficulty accepting that she is gone. He does not leave the house much anymore and continues to set a place for her at the kitchen table on special occasions. He says, “Some nights in bed, I swear I can hear her in the living room.”

How would you proceed with this patient?

* The names of the patient and his spouse have been changed to protect their identities.

After the loss of a loved one, grief is a natural response to the separation and stress that go along with the death. Most people, after suffering a loss, experience distress that varies in intensity and gradually decreases over time. Thus, the grieving individual does not act as they would normally if they were not bereaved. However, gains are generally made month by month, and most people adjust to the grief and adapt their lives after some time dealing with the absence of the loved one.1

There’s grief, and then there’s complicated grief

For about 2% to 4% of the population who have experienced a significant loss, complicated grief is an issue.2 As its hallmark, complicated grief exceeds the typical amount of time (6-12 months) that people need to recover from a loss. Prevalence has been estimated at 10% to 20% among grieving individuals for whom the death being grieved was that of a romantic partner or child.2 At increased risk for this disorder are women older than 60 years, patients diagnosed with depression or substance abuse, individuals under financial strain, and those who have experienced a violent or sudden loss.3

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) has conceptualized complicated grief with the name, persistent complex bereavement disorder (PCBD).4 While the guidelines for the definition are still in progress, several specified symptoms must have been present for at least 6 months to a year or more (TABLE 14). For instance, the patient has been ruminating about the death, has been unable to accept the death, or has felt shocked or numb. They may also experience anger, have difficulty trusting others, and be preoccupied with the deceased (eg, sense they can hear their lost loved one, feel the loved one’s pain for them). Symptoms of PCBD may also include experiencing vivid reminders of the loss and avoiding situations that bring up thoughts about the death.4 (Of note: A grief diagnosis in ICD-10 is captured by the code F43.21; however, there is no specific code for complicated grief or PCBD.)

PCBD is a “condition for further study” in DSM-5; it was omitted from DSM-IV only after much debate. One reason for its omission was concern that clinicians might “pathologize” grief more than it needs to be.5 Grief is regarded as a natural process that might be stymied by a formal diagnosis leading to medical treatment.

Shifting the grief diagnosis paradigm

One new development is that recently bereaved patients can be diagnosed with depression if they meet the criteria for that diagnosis. In the past, someone who met criteria for major depression would be excluded from that diagnosis if the depression ensued from grief. DSM-5 no longer makes that distinction.4 Given this diagnostic shift, one might wonder about the difference between PCBD and depression, particularly if the patient is a grieving individual with a current diagnosis of depression.5

Continue to: Differences between PCBD and major depression

Differences between PCBD and major depression. While antidepressant medication is helpful for patients with moderate-to-severe depression, it has thus far been less helpful for those solely experiencing complicated grief.6 The same holds true for traditional psychotherapy. While family physicians can confidently refer people to psychotherapy for depression, it is not as efficacious as focused therapy designed for those with PCBD.6

Other differences between PCBD and major depression involve the constructs of guilt and yearning. Depressed patients typically feel guilty about a number of things, while those with complicated grief have specific death-focused guilt.7 Depressed people generally do not yearn, while those with grief yearn for their loved one. Finally, and most concerning to clinicians, some patients with PCBD have suicidal thoughts.8 While such thoughts in depression are often linked to hopelessness, suicidal thoughts for grieving individuals are generally driven by a desire to be reunited with the deceased loved one.

While these differences may help in making treatment decisions, there can be overlap between depression and complicated grief. As with many mental health diagnoses, major depression and PCBD are not mutually exclusive.4

The role of hospice. Another factor sometimes associated with complicated grief is any hindrance to the survivor’s ability to communicate or say goodbye to the loved one at the end of life.9 This may be avoided if the loved one is in hospice care and is not subjected to procedures that impair communication (ie, ventilator use, sedation). Medicare requires that certified hospice programs offer bereavement services for 1 year following patient death.10 Some hospice providers even offer bereavement services to those not enrolled in hospice. However, evidence indicates that only about 30% of bereaved caregivers take advantage of hospice bereavement services.11 Family physicians may help patients during this process by providing an early referral to hospice services and recommending bereavement counseling. Referral to hospice care can also facilitate discussions that the patient may need to have with the physician or others regarding spirituality. Hospital chaplains can also be referred or get involved with patients and family upon request.

Assessment focal points and tools

As is the case with most mental health concerns, primary care is at the forefront of early assessment. Evaluation of grief is an ongoing process and is multifactorial. One focus is the intensity of the grief. Is the patient reacting to the loss in a way that is disproportionately severe when compared with others who grieve? Another factor is the time elapsed since the loss. If the loss was more than 6 months ago, the patient should have made some progress. Assess grieving patients at around 6 months post-loss to determine how they are handling grief. As mentioned, DSM-5 has criteria for PCBD that providers can use in determining a patient’s grief status. Also needed are assessments for the other DSM-5 issues often associated with loss: depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Continue to: While no clinical measure is perfect...

While no clinical measure is perfect, there are tools that can help in assessing patients for the possibility of complicated grief (TABLE 2). Also keep in mind that no measure can make a diagnosis of PCBD, as it is a clinical judgment, not a score on a scale. Furthermore, there is no measure that can accurately predict future complicated grief.6 In most busy practices, the Brief Grief Questionnaire (http://www.massgeneral.org/psychiatry/assets/Brief_Grief_Questionnaire.pdf ) would be the easiest tool to administer, but a case could be made for any of the measures.

Treatment

The literature base emphasizes that PCBD treatment requires a different focus than that applied to uncomplicated grief. And while most people with major depression will respond to medication and psychotherapy, there are provisos to keep in mind when depression is associated with complicated grief.

Complicated grief treatment (CGT) has been studied extensively.6 This treatment combines some of the tenets of evidence-based PTSD treatments, interpersonal therapy for grief, and cognitive behavioral therapy. CGT is generally an individual treatment, although group therapy using some of its tenets can also be effective. According to complicated grief researchers, tasks to accomplish in CGT include establishing a “new normal” following the loss, promoting self-regulation in the grieving, building social connections, and setting aspirational goals for the future.6 Other goals are to revisit the world, tell stories of the past, and relive old memories in a more positive light. Common suggestions in CGT that run parallel to conventional thoughts on dealing with grief include increasing time outside the home, getting more involved interpersonally, and increasing mindfulness-based practices.

A second-line evidence-based treatment for PCBD is the use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).6 Some studies have found benefit from SSRI treatment, although the findings are preliminary and modest.12 One observational study examined patients who had recently experienced loss and were receiving CGT with or without medication. Researchers found that CGT with medication (citalopram) led to a 61% positive response rate while CGT alone led to a 41% response rate.13 Thus, findings revealed some benefit to combining an antidepressant with CGT, indicating that SSRIs may be helpful as an adjunct treatment.

THE CASE

Al was treated for complicated grief by his family physician and a psychologist for approximately a year. He responded well to an SSRI and received psychotherapy that focused on the tenets of CGT. Prior to his last psychotherapy visit, he reported leaving the house regularly to dine at restaurants and meet up with co-workers after hours. He said, “I still miss Vera quite a bit, but I know that I feel better.”

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; [email protected]

THE CASE

Al* is a 48-year-old patient whose wife, Vera, died of complications from chronic illness 14 months ago. Al thinks about Vera constantly and says he still has difficulty accepting that she is gone. He does not leave the house much anymore and continues to set a place for her at the kitchen table on special occasions. He says, “Some nights in bed, I swear I can hear her in the living room.”

How would you proceed with this patient?

* The names of the patient and his spouse have been changed to protect their identities.

After the loss of a loved one, grief is a natural response to the separation and stress that go along with the death. Most people, after suffering a loss, experience distress that varies in intensity and gradually decreases over time. Thus, the grieving individual does not act as they would normally if they were not bereaved. However, gains are generally made month by month, and most people adjust to the grief and adapt their lives after some time dealing with the absence of the loved one.1

There’s grief, and then there’s complicated grief

For about 2% to 4% of the population who have experienced a significant loss, complicated grief is an issue.2 As its hallmark, complicated grief exceeds the typical amount of time (6-12 months) that people need to recover from a loss. Prevalence has been estimated at 10% to 20% among grieving individuals for whom the death being grieved was that of a romantic partner or child.2 At increased risk for this disorder are women older than 60 years, patients diagnosed with depression or substance abuse, individuals under financial strain, and those who have experienced a violent or sudden loss.3

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) has conceptualized complicated grief with the name, persistent complex bereavement disorder (PCBD).4 While the guidelines for the definition are still in progress, several specified symptoms must have been present for at least 6 months to a year or more (TABLE 14). For instance, the patient has been ruminating about the death, has been unable to accept the death, or has felt shocked or numb. They may also experience anger, have difficulty trusting others, and be preoccupied with the deceased (eg, sense they can hear their lost loved one, feel the loved one’s pain for them). Symptoms of PCBD may also include experiencing vivid reminders of the loss and avoiding situations that bring up thoughts about the death.4 (Of note: A grief diagnosis in ICD-10 is captured by the code F43.21; however, there is no specific code for complicated grief or PCBD.)

PCBD is a “condition for further study” in DSM-5; it was omitted from DSM-IV only after much debate. One reason for its omission was concern that clinicians might “pathologize” grief more than it needs to be.5 Grief is regarded as a natural process that might be stymied by a formal diagnosis leading to medical treatment.

Shifting the grief diagnosis paradigm

One new development is that recently bereaved patients can be diagnosed with depression if they meet the criteria for that diagnosis. In the past, someone who met criteria for major depression would be excluded from that diagnosis if the depression ensued from grief. DSM-5 no longer makes that distinction.4 Given this diagnostic shift, one might wonder about the difference between PCBD and depression, particularly if the patient is a grieving individual with a current diagnosis of depression.5

Continue to: Differences between PCBD and major depression

Differences between PCBD and major depression. While antidepressant medication is helpful for patients with moderate-to-severe depression, it has thus far been less helpful for those solely experiencing complicated grief.6 The same holds true for traditional psychotherapy. While family physicians can confidently refer people to psychotherapy for depression, it is not as efficacious as focused therapy designed for those with PCBD.6

Other differences between PCBD and major depression involve the constructs of guilt and yearning. Depressed patients typically feel guilty about a number of things, while those with complicated grief have specific death-focused guilt.7 Depressed people generally do not yearn, while those with grief yearn for their loved one. Finally, and most concerning to clinicians, some patients with PCBD have suicidal thoughts.8 While such thoughts in depression are often linked to hopelessness, suicidal thoughts for grieving individuals are generally driven by a desire to be reunited with the deceased loved one.

While these differences may help in making treatment decisions, there can be overlap between depression and complicated grief. As with many mental health diagnoses, major depression and PCBD are not mutually exclusive.4

The role of hospice. Another factor sometimes associated with complicated grief is any hindrance to the survivor’s ability to communicate or say goodbye to the loved one at the end of life.9 This may be avoided if the loved one is in hospice care and is not subjected to procedures that impair communication (ie, ventilator use, sedation). Medicare requires that certified hospice programs offer bereavement services for 1 year following patient death.10 Some hospice providers even offer bereavement services to those not enrolled in hospice. However, evidence indicates that only about 30% of bereaved caregivers take advantage of hospice bereavement services.11 Family physicians may help patients during this process by providing an early referral to hospice services and recommending bereavement counseling. Referral to hospice care can also facilitate discussions that the patient may need to have with the physician or others regarding spirituality. Hospital chaplains can also be referred or get involved with patients and family upon request.

Assessment focal points and tools

As is the case with most mental health concerns, primary care is at the forefront of early assessment. Evaluation of grief is an ongoing process and is multifactorial. One focus is the intensity of the grief. Is the patient reacting to the loss in a way that is disproportionately severe when compared with others who grieve? Another factor is the time elapsed since the loss. If the loss was more than 6 months ago, the patient should have made some progress. Assess grieving patients at around 6 months post-loss to determine how they are handling grief. As mentioned, DSM-5 has criteria for PCBD that providers can use in determining a patient’s grief status. Also needed are assessments for the other DSM-5 issues often associated with loss: depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Continue to: While no clinical measure is perfect...

While no clinical measure is perfect, there are tools that can help in assessing patients for the possibility of complicated grief (TABLE 2). Also keep in mind that no measure can make a diagnosis of PCBD, as it is a clinical judgment, not a score on a scale. Furthermore, there is no measure that can accurately predict future complicated grief.6 In most busy practices, the Brief Grief Questionnaire (http://www.massgeneral.org/psychiatry/assets/Brief_Grief_Questionnaire.pdf ) would be the easiest tool to administer, but a case could be made for any of the measures.

Treatment

The literature base emphasizes that PCBD treatment requires a different focus than that applied to uncomplicated grief. And while most people with major depression will respond to medication and psychotherapy, there are provisos to keep in mind when depression is associated with complicated grief.

Complicated grief treatment (CGT) has been studied extensively.6 This treatment combines some of the tenets of evidence-based PTSD treatments, interpersonal therapy for grief, and cognitive behavioral therapy. CGT is generally an individual treatment, although group therapy using some of its tenets can also be effective. According to complicated grief researchers, tasks to accomplish in CGT include establishing a “new normal” following the loss, promoting self-regulation in the grieving, building social connections, and setting aspirational goals for the future.6 Other goals are to revisit the world, tell stories of the past, and relive old memories in a more positive light. Common suggestions in CGT that run parallel to conventional thoughts on dealing with grief include increasing time outside the home, getting more involved interpersonally, and increasing mindfulness-based practices.

A second-line evidence-based treatment for PCBD is the use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).6 Some studies have found benefit from SSRI treatment, although the findings are preliminary and modest.12 One observational study examined patients who had recently experienced loss and were receiving CGT with or without medication. Researchers found that CGT with medication (citalopram) led to a 61% positive response rate while CGT alone led to a 41% response rate.13 Thus, findings revealed some benefit to combining an antidepressant with CGT, indicating that SSRIs may be helpful as an adjunct treatment.

THE CASE

Al was treated for complicated grief by his family physician and a psychologist for approximately a year. He responded well to an SSRI and received psychotherapy that focused on the tenets of CGT. Prior to his last psychotherapy visit, he reported leaving the house regularly to dine at restaurants and meet up with co-workers after hours. He said, “I still miss Vera quite a bit, but I know that I feel better.”

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; [email protected]

1. Cozza SJ, Fisher JE, Mauro C, et al. Performance of DSM-5 persistent complex bereavement disorder criteria in a community sample of bereaved military family members. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:919-929.

2. Kersting A, Brähler E, Glaesmer H, et al. Prevalence of complicated grief in a representative population-based sample. J Affect Disord. 2011;131:339-343.

3. Fujisawa D, Miyashita M, Nakajima S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of complicated grief in general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;127:352-358.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: APA Press; 2013.

5. Shear MK, Simon N, Wall M, et al. Complicated grief and related issues for DSM-5. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:103-117.

6. Shear MK. Clinical Practice. Complicated grief. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:153-160.

7. Wolfelt AD. Counseling Skills for Companioning the Mourner: The Fundamentals of Effective Grief Counseling. Fort Collins, CO: Companion Press; 2016.

8. Szanto K, Shear MK, Houck PR, et al. Indirect self-destructive behavior and overt suicidality in patients with complicated grief. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:233-239.

9. Otani H, Yoshida S, Morita T, et al. Meaningful communication before death, but not present at the time of death itself, is associated with better outcomes on measures of depression and complicated grief among bereaved family members of cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54:273-279.

10. CMS. Medicare benefit policy manual: coverage of hospice services under hospital insurance. www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/bp102c09.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2018.

11. Cherlin E, Barry LC, Prigerson H, et al. Bereavement services for family caregivers: how often used, why, and why not. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:148–158.

12. Bui E, Nidal-Vicens M, Simon NM. Pharmacologic approaches to the treatment of complicated grief: rationale and a brief review of the literature. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012;14:149-157.

13. Shear MK, Reynolds CF 3rd, Simon NM, et al. Optimizing treatment of complicated grief: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:685-694.

1. Cozza SJ, Fisher JE, Mauro C, et al. Performance of DSM-5 persistent complex bereavement disorder criteria in a community sample of bereaved military family members. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:919-929.

2. Kersting A, Brähler E, Glaesmer H, et al. Prevalence of complicated grief in a representative population-based sample. J Affect Disord. 2011;131:339-343.

3. Fujisawa D, Miyashita M, Nakajima S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of complicated grief in general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;127:352-358.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: APA Press; 2013.

5. Shear MK, Simon N, Wall M, et al. Complicated grief and related issues for DSM-5. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:103-117.

6. Shear MK. Clinical Practice. Complicated grief. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:153-160.

7. Wolfelt AD. Counseling Skills for Companioning the Mourner: The Fundamentals of Effective Grief Counseling. Fort Collins, CO: Companion Press; 2016.

8. Szanto K, Shear MK, Houck PR, et al. Indirect self-destructive behavior and overt suicidality in patients with complicated grief. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:233-239.

9. Otani H, Yoshida S, Morita T, et al. Meaningful communication before death, but not present at the time of death itself, is associated with better outcomes on measures of depression and complicated grief among bereaved family members of cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54:273-279.

10. CMS. Medicare benefit policy manual: coverage of hospice services under hospital insurance. www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/bp102c09.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2018.

11. Cherlin E, Barry LC, Prigerson H, et al. Bereavement services for family caregivers: how often used, why, and why not. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:148–158.

12. Bui E, Nidal-Vicens M, Simon NM. Pharmacologic approaches to the treatment of complicated grief: rationale and a brief review of the literature. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012;14:149-157.

13. Shear MK, Reynolds CF 3rd, Simon NM, et al. Optimizing treatment of complicated grief: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:685-694.