User login

It has been almost 10 years since the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended administration of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls and young women up to 26 years of age. Routine administration in preteen boys and young adult males up to 21 years of age was recommended in 2011. An HPV series should be completed by 13 years. So how well are we protecting our patients?

Vaccine coverage

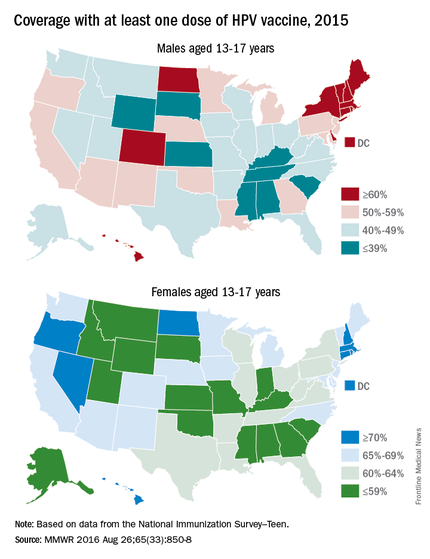

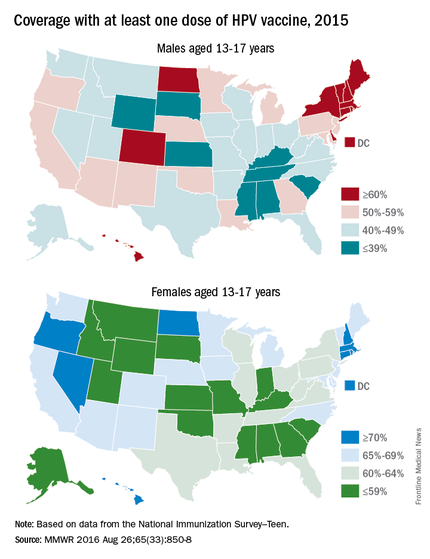

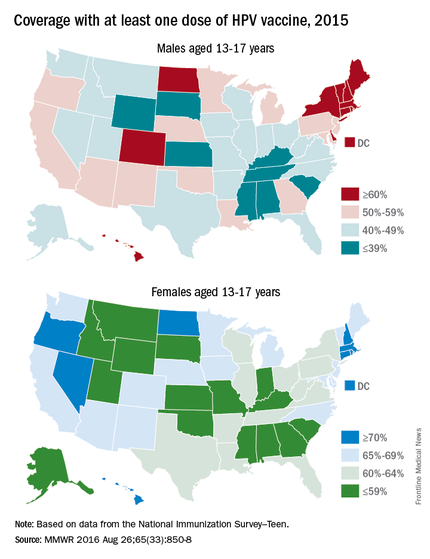

The National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen) monitors vaccine coverage annually among adolescents 13-17 years. Data are obtained from individuals from the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas (MMWR. 2016 Aug 26;65[33]:850-8).

HPV vaccination continues to lag behind Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV), although each one is recommended to be administered at the 11- to 12-year visit. In 2015, coverage for receiving at least one dose of HPV vaccine among females was almost 62.8 % and for at least three doses was 41.9%; among males, coverage with at least one dose was 49.8% and for at least three doses was 28.1%. Compared with 2014, coverage for at least one dose of HPV vaccine increased 2.8% in females and 8.1% in males. Males also had a 7.6% for receipt of at least two doses of HPV vaccine, compared with 2014. HPV vaccine coverage in females aged 13 and younger also was lower than for those aged 15 and older. Coverage did not differ for males based on age.

HPV vaccination coverage also differed by state. In 2015, 28 states reported increased coverage in males, but only 7 states had increased coverage in females. Among all adolescents, coverage with at least one dose of HPV vaccine was 56.1%, at least two doses was 45.4%, and at least three doses was 34.9%. In contrast, 86.4% of all adolescents received at least one dose of Tdap, and 81.3% received at least one dose of MCV.

HPV-associated cancers

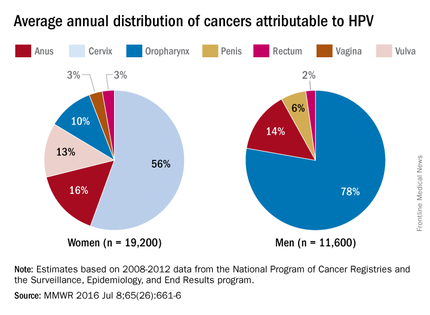

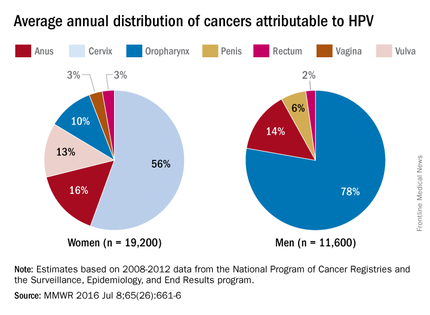

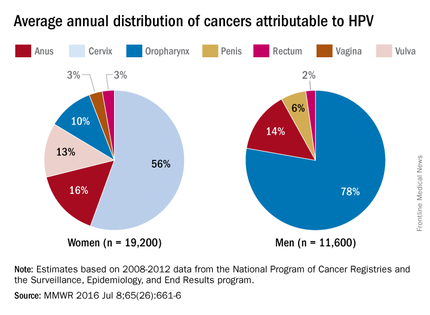

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in both men and women. It is estimated that 79 million Americans are infected and 14 million new infections occur annually, usually in teens and young adults. Although most infections are asymptomatic and clear spontaneously, persistent infection with oncogenic types can progress to cancer. Cervical and oropharyngeal cancer were the most common HPV-associated cancers in women and men, respectively, in 2008-2012 (MMWR 2016;65:661-6).

All three HPV vaccines protect against HPV types 16 and 18. These types are estimated to account for the majority of cervical and oropharyngeal cancers, 66% and 62%, respectively. The additional types in the 9-valent HPV will protect against HPV types that cause approximately 15% of cervical cancers.

The association between HPV and cancer is clear. So why isn’t this vaccine being embraced? HPV vaccine is all about cancer prevention. Isn’t it? What are the barriers to HPV vaccination? Are parental concerns the only barrier? Are we recommending this vaccine as strongly as others?

Vaccine safety and efficacy

Safety has been a concern voiced by some parents. Collectively, HPV vaccines were studied in more than 95,000 individuals prior to licensure. Almost 90 million doses of vaccine have been distributed in the United States and more than 183 million, worldwide. The federal government utilizes three systems to monitor vaccine safety once a vaccine is licensed: The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), and the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network. Ongoing safety studies also are conducted by vaccine manufacturers. Since licensure, no serious safety concerns have been identified. Postvaccination syncope, first identified in the VAERS database in 2006, has declined since observation post injection was recommended by ACIP. Multiple studies in the United States and abroad have not demonstrated a causal association with HPV vaccine and any autoimmune and/or neurologic condition or increased risk for thromboembolism.

Mélanie Drolet, PhD, and her colleagues reviewed 20 studies in nine countries with at least 50% coverage in female adolescents aged 13-19 years. There was a 68% reduction in the prevalence of HPV types 16 and 18 and a 61% reduction in anal warts in the postvaccine era (Lancet Infect Dis. 2015 May;15[5]:565-80). Studies also indicate there is no indication of waning immunity.

Parental perceptions

Some parents feel the vaccine is not necessary because their child is not sexually active and/or is not at risk for acquiring a sexually transmitted infection. Others opt to delay initiation. NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) data from 2011 to 2014 revealed that among females aged 14-26 years whose age was known at the time of their first dose of HPV vaccine, 43% had reported having sex before or in the same year that they received their first dose.

One consistent reason parents indicate for not vaccinating is the lack of recommendation from their child’s health provider. Differences in age and sex recommendations also are reported. NIS-Teen 2013 demonstrated that parents of girls were more likely than parents of boys to receive a provider recommendation (65% vs.42%.) Only 29% of female parents indicated they’d received a provider recommendation to have their child vaccinated with HPV by ages 11-12 years.

Mandy A. Allison, MD, and her colleagues reviewed primary care physician perspectives about HPV vaccine in a national survey among 364 pediatricians and 218 family physicians (FPs). Although 84% of pediatricians and 75% of FPs indicated they always discuss HPV vaccination, only 60% of pediatricians and 59% of FPs strongly recommend HPV vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls; for boys it was 52% and 41%. More than half reported parental deferral. For pediatricians who almost never discussed the topic, the reasons included that the patient was not sexually active (54%), the child was young (38%), and the patient was already receiving other vaccines (35%) (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137[2]:e20152488).

Providers can be influenced by their perceptions of what value parents place on vaccines. In one study, parents were asked to put a value on specific vaccines. Providers were then asked to estimate how parents ranked the vaccines on a scale of 0-10. Providers underestimated the value placed on HPV vaccine (9.3 vs 5.2) (Vaccine 2014;32:579-84).

Improving HPV coverage: Preventing future HPV-related cancers

HPV vaccine should be recommended with as much conviction as Tdap and MCV at the 11- to 12-year visit for both girls and boys. Administration of all three should occur on the same day. Clinician recommendation is the No. 1 reason parents decide to vaccinate. The mantra “same way, same day” should become synonymous with the 11- to 12-year visit. All who have contact with the patient, beginning with the front desk staff, should know the importance of HPV vaccine, and when and why it is recommended. Often, families spend more time with support staff and have discussions prior to interacting with you.

Anticipate questions about HPV. Why give the vaccine when the child is so young and not sexually active? Is my child really at risk? Is it safe? I read on the Internet. … Questions should be interpreted as a need for additional information and reassurance from you.

Remember to emphasize that HPV vaccine is important because it prevents cancer and it is most effective prior to exposure to HPV.

Additional resources to facilitate your discussions about HPV can be found at www.cdc.gov/hpv.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

It has been almost 10 years since the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended administration of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls and young women up to 26 years of age. Routine administration in preteen boys and young adult males up to 21 years of age was recommended in 2011. An HPV series should be completed by 13 years. So how well are we protecting our patients?

Vaccine coverage

The National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen) monitors vaccine coverage annually among adolescents 13-17 years. Data are obtained from individuals from the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas (MMWR. 2016 Aug 26;65[33]:850-8).

HPV vaccination continues to lag behind Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV), although each one is recommended to be administered at the 11- to 12-year visit. In 2015, coverage for receiving at least one dose of HPV vaccine among females was almost 62.8 % and for at least three doses was 41.9%; among males, coverage with at least one dose was 49.8% and for at least three doses was 28.1%. Compared with 2014, coverage for at least one dose of HPV vaccine increased 2.8% in females and 8.1% in males. Males also had a 7.6% for receipt of at least two doses of HPV vaccine, compared with 2014. HPV vaccine coverage in females aged 13 and younger also was lower than for those aged 15 and older. Coverage did not differ for males based on age.

HPV vaccination coverage also differed by state. In 2015, 28 states reported increased coverage in males, but only 7 states had increased coverage in females. Among all adolescents, coverage with at least one dose of HPV vaccine was 56.1%, at least two doses was 45.4%, and at least three doses was 34.9%. In contrast, 86.4% of all adolescents received at least one dose of Tdap, and 81.3% received at least one dose of MCV.

HPV-associated cancers

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in both men and women. It is estimated that 79 million Americans are infected and 14 million new infections occur annually, usually in teens and young adults. Although most infections are asymptomatic and clear spontaneously, persistent infection with oncogenic types can progress to cancer. Cervical and oropharyngeal cancer were the most common HPV-associated cancers in women and men, respectively, in 2008-2012 (MMWR 2016;65:661-6).

All three HPV vaccines protect against HPV types 16 and 18. These types are estimated to account for the majority of cervical and oropharyngeal cancers, 66% and 62%, respectively. The additional types in the 9-valent HPV will protect against HPV types that cause approximately 15% of cervical cancers.

The association between HPV and cancer is clear. So why isn’t this vaccine being embraced? HPV vaccine is all about cancer prevention. Isn’t it? What are the barriers to HPV vaccination? Are parental concerns the only barrier? Are we recommending this vaccine as strongly as others?

Vaccine safety and efficacy

Safety has been a concern voiced by some parents. Collectively, HPV vaccines were studied in more than 95,000 individuals prior to licensure. Almost 90 million doses of vaccine have been distributed in the United States and more than 183 million, worldwide. The federal government utilizes three systems to monitor vaccine safety once a vaccine is licensed: The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), and the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network. Ongoing safety studies also are conducted by vaccine manufacturers. Since licensure, no serious safety concerns have been identified. Postvaccination syncope, first identified in the VAERS database in 2006, has declined since observation post injection was recommended by ACIP. Multiple studies in the United States and abroad have not demonstrated a causal association with HPV vaccine and any autoimmune and/or neurologic condition or increased risk for thromboembolism.

Mélanie Drolet, PhD, and her colleagues reviewed 20 studies in nine countries with at least 50% coverage in female adolescents aged 13-19 years. There was a 68% reduction in the prevalence of HPV types 16 and 18 and a 61% reduction in anal warts in the postvaccine era (Lancet Infect Dis. 2015 May;15[5]:565-80). Studies also indicate there is no indication of waning immunity.

Parental perceptions

Some parents feel the vaccine is not necessary because their child is not sexually active and/or is not at risk for acquiring a sexually transmitted infection. Others opt to delay initiation. NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) data from 2011 to 2014 revealed that among females aged 14-26 years whose age was known at the time of their first dose of HPV vaccine, 43% had reported having sex before or in the same year that they received their first dose.

One consistent reason parents indicate for not vaccinating is the lack of recommendation from their child’s health provider. Differences in age and sex recommendations also are reported. NIS-Teen 2013 demonstrated that parents of girls were more likely than parents of boys to receive a provider recommendation (65% vs.42%.) Only 29% of female parents indicated they’d received a provider recommendation to have their child vaccinated with HPV by ages 11-12 years.

Mandy A. Allison, MD, and her colleagues reviewed primary care physician perspectives about HPV vaccine in a national survey among 364 pediatricians and 218 family physicians (FPs). Although 84% of pediatricians and 75% of FPs indicated they always discuss HPV vaccination, only 60% of pediatricians and 59% of FPs strongly recommend HPV vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls; for boys it was 52% and 41%. More than half reported parental deferral. For pediatricians who almost never discussed the topic, the reasons included that the patient was not sexually active (54%), the child was young (38%), and the patient was already receiving other vaccines (35%) (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137[2]:e20152488).

Providers can be influenced by their perceptions of what value parents place on vaccines. In one study, parents were asked to put a value on specific vaccines. Providers were then asked to estimate how parents ranked the vaccines on a scale of 0-10. Providers underestimated the value placed on HPV vaccine (9.3 vs 5.2) (Vaccine 2014;32:579-84).

Improving HPV coverage: Preventing future HPV-related cancers

HPV vaccine should be recommended with as much conviction as Tdap and MCV at the 11- to 12-year visit for both girls and boys. Administration of all three should occur on the same day. Clinician recommendation is the No. 1 reason parents decide to vaccinate. The mantra “same way, same day” should become synonymous with the 11- to 12-year visit. All who have contact with the patient, beginning with the front desk staff, should know the importance of HPV vaccine, and when and why it is recommended. Often, families spend more time with support staff and have discussions prior to interacting with you.

Anticipate questions about HPV. Why give the vaccine when the child is so young and not sexually active? Is my child really at risk? Is it safe? I read on the Internet. … Questions should be interpreted as a need for additional information and reassurance from you.

Remember to emphasize that HPV vaccine is important because it prevents cancer and it is most effective prior to exposure to HPV.

Additional resources to facilitate your discussions about HPV can be found at www.cdc.gov/hpv.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

It has been almost 10 years since the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended administration of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls and young women up to 26 years of age. Routine administration in preteen boys and young adult males up to 21 years of age was recommended in 2011. An HPV series should be completed by 13 years. So how well are we protecting our patients?

Vaccine coverage

The National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen) monitors vaccine coverage annually among adolescents 13-17 years. Data are obtained from individuals from the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas (MMWR. 2016 Aug 26;65[33]:850-8).

HPV vaccination continues to lag behind Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV), although each one is recommended to be administered at the 11- to 12-year visit. In 2015, coverage for receiving at least one dose of HPV vaccine among females was almost 62.8 % and for at least three doses was 41.9%; among males, coverage with at least one dose was 49.8% and for at least three doses was 28.1%. Compared with 2014, coverage for at least one dose of HPV vaccine increased 2.8% in females and 8.1% in males. Males also had a 7.6% for receipt of at least two doses of HPV vaccine, compared with 2014. HPV vaccine coverage in females aged 13 and younger also was lower than for those aged 15 and older. Coverage did not differ for males based on age.

HPV vaccination coverage also differed by state. In 2015, 28 states reported increased coverage in males, but only 7 states had increased coverage in females. Among all adolescents, coverage with at least one dose of HPV vaccine was 56.1%, at least two doses was 45.4%, and at least three doses was 34.9%. In contrast, 86.4% of all adolescents received at least one dose of Tdap, and 81.3% received at least one dose of MCV.

HPV-associated cancers

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in both men and women. It is estimated that 79 million Americans are infected and 14 million new infections occur annually, usually in teens and young adults. Although most infections are asymptomatic and clear spontaneously, persistent infection with oncogenic types can progress to cancer. Cervical and oropharyngeal cancer were the most common HPV-associated cancers in women and men, respectively, in 2008-2012 (MMWR 2016;65:661-6).

All three HPV vaccines protect against HPV types 16 and 18. These types are estimated to account for the majority of cervical and oropharyngeal cancers, 66% and 62%, respectively. The additional types in the 9-valent HPV will protect against HPV types that cause approximately 15% of cervical cancers.

The association between HPV and cancer is clear. So why isn’t this vaccine being embraced? HPV vaccine is all about cancer prevention. Isn’t it? What are the barriers to HPV vaccination? Are parental concerns the only barrier? Are we recommending this vaccine as strongly as others?

Vaccine safety and efficacy

Safety has been a concern voiced by some parents. Collectively, HPV vaccines were studied in more than 95,000 individuals prior to licensure. Almost 90 million doses of vaccine have been distributed in the United States and more than 183 million, worldwide. The federal government utilizes three systems to monitor vaccine safety once a vaccine is licensed: The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), and the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network. Ongoing safety studies also are conducted by vaccine manufacturers. Since licensure, no serious safety concerns have been identified. Postvaccination syncope, first identified in the VAERS database in 2006, has declined since observation post injection was recommended by ACIP. Multiple studies in the United States and abroad have not demonstrated a causal association with HPV vaccine and any autoimmune and/or neurologic condition or increased risk for thromboembolism.

Mélanie Drolet, PhD, and her colleagues reviewed 20 studies in nine countries with at least 50% coverage in female adolescents aged 13-19 years. There was a 68% reduction in the prevalence of HPV types 16 and 18 and a 61% reduction in anal warts in the postvaccine era (Lancet Infect Dis. 2015 May;15[5]:565-80). Studies also indicate there is no indication of waning immunity.

Parental perceptions

Some parents feel the vaccine is not necessary because their child is not sexually active and/or is not at risk for acquiring a sexually transmitted infection. Others opt to delay initiation. NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) data from 2011 to 2014 revealed that among females aged 14-26 years whose age was known at the time of their first dose of HPV vaccine, 43% had reported having sex before or in the same year that they received their first dose.

One consistent reason parents indicate for not vaccinating is the lack of recommendation from their child’s health provider. Differences in age and sex recommendations also are reported. NIS-Teen 2013 demonstrated that parents of girls were more likely than parents of boys to receive a provider recommendation (65% vs.42%.) Only 29% of female parents indicated they’d received a provider recommendation to have their child vaccinated with HPV by ages 11-12 years.

Mandy A. Allison, MD, and her colleagues reviewed primary care physician perspectives about HPV vaccine in a national survey among 364 pediatricians and 218 family physicians (FPs). Although 84% of pediatricians and 75% of FPs indicated they always discuss HPV vaccination, only 60% of pediatricians and 59% of FPs strongly recommend HPV vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls; for boys it was 52% and 41%. More than half reported parental deferral. For pediatricians who almost never discussed the topic, the reasons included that the patient was not sexually active (54%), the child was young (38%), and the patient was already receiving other vaccines (35%) (Pediatrics. 2016 Feb;137[2]:e20152488).

Providers can be influenced by their perceptions of what value parents place on vaccines. In one study, parents were asked to put a value on specific vaccines. Providers were then asked to estimate how parents ranked the vaccines on a scale of 0-10. Providers underestimated the value placed on HPV vaccine (9.3 vs 5.2) (Vaccine 2014;32:579-84).

Improving HPV coverage: Preventing future HPV-related cancers

HPV vaccine should be recommended with as much conviction as Tdap and MCV at the 11- to 12-year visit for both girls and boys. Administration of all three should occur on the same day. Clinician recommendation is the No. 1 reason parents decide to vaccinate. The mantra “same way, same day” should become synonymous with the 11- to 12-year visit. All who have contact with the patient, beginning with the front desk staff, should know the importance of HPV vaccine, and when and why it is recommended. Often, families spend more time with support staff and have discussions prior to interacting with you.

Anticipate questions about HPV. Why give the vaccine when the child is so young and not sexually active? Is my child really at risk? Is it safe? I read on the Internet. … Questions should be interpreted as a need for additional information and reassurance from you.

Remember to emphasize that HPV vaccine is important because it prevents cancer and it is most effective prior to exposure to HPV.

Additional resources to facilitate your discussions about HPV can be found at www.cdc.gov/hpv.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.