User login

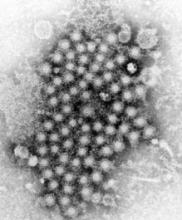

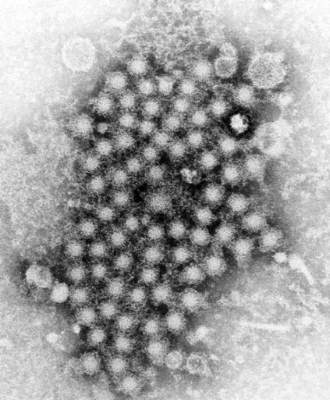

SAN DIEGO – Despite better therapies, deaths from hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection continue to rise, indicating poor penetrance of medications and care to patients who need them, Dr. Scott Holmberg said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“Deaths in chronic HCV–infected persons, even when grossly under-enumerated on death certificates, far outstrip deaths from 60 other infectious conditions reportable to CDC,” said Dr. Holmberg of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Division of Viral Hepatitis in Atlanta.

Drugs for chronic HCV infection have vastly improved in the past several years, yielding far better rates of sustained viral response (SVR) and high chances of cure after 8-24 weeks of treatment. To see if better antiviral therapies have affected HCV mortality rates, Dr. Holmberg and his associates studied ICD-9 data from Multiple Cause of Death records for all U.S. death certificates between 2003 and 2013. They divided deaths that were linked to HCV or 60 other nationally notifiable infectious diseases by U.S. Census numbers for the same year. They also examined data from the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1055-61), which includes patients presumed to have adequate access to HCV treatment.

Chronic HCV-related deaths climbed from about 12,000 annually in 2003 to more than 19,000 in 2013, said Dr. Holmberg. In contrast, deaths from the 60 other reportable infectious diseases dropped from about 25,000 annually to below 20,000 per year. Annual deaths tied to HIV infection ranked second behind HCV at about 8,800, followed by Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA), hepatitis B virus, tuberculosis, and pneumococcal disease. “This does not include 4,444 adult influenza deaths, but does include 165 childhood influenza deaths in 2013,” Dr. Holmberg noted.

The analysis of the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study revealed a doubling in mortality from chronic HCV infection among patients who should have had adequate access to treatment, according to Dr. Holmberg. For every 100 person-years of observation, about 2.5 people died from consequences of chronic HCV infection in 2007, compared with about 5.5 in 2013, he said. “Hidden mortality from HCV is considerable,” he added. “Only 19% of HCV patients who died had their infection noted anywhere on their death certificates, despite the fact that more than 75% had premortem evidence of liver disease.”

Uptake of sofosbuvir-based regimens more than quintupled in the second quarter of 2015, compared with a year earlier, according to data from Gilead Sciences presented by Dr. Holmberg. But high drug costs have spurred state Medicaid programs and private payers to stipulate many preapproval requirements, he noted. Patients must be drug and alcohol free for at least 6 months, and in many states, must provide evidence of liver scarring from a recent biopsy or FibroScan, which is not always easy to access. “This is often a barrier,” Dr. Holmberg said. “For those in more rural areas, finding a specialist, as required by many state Medicaid offices, can be very difficult.”

And there are even more obstacles. Many clinicians still see HCV as a “benign condition,” and patients often have other urgent health, social, or financial problems, Dr. Holmberg said. The public, for its part, may not prioritize infectious diseases. “These patients lack a strong advocacy group,” he added. “Most are former injection drug users, and the public is often reluctant to help them.”

So what are the measurable results of these barriers? Among about 3.2 million individuals in the United States with chronic HCV infection, only half were ever tested for HCV, 38% received some sort of care related to their infection, 11% were treated, and 6% achieved SVR, Dr. Holmberg and his associates noted in a perspective piece (N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1859-861).

At the same time, the United States faces an emerging epidemic of new HCV infections in nonurban areas among young persons who inject drugs (MMWR. 64;453-8). “This is really a tale of two epidemics,” he added. “Control of the chronic and the acute outbreaks will require a multipronged approach, with interventions along a testing to cure continuum of care.”

Dr. Holmberg and his associates reported their findings at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. The researchers reported no funding sources and had no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Despite better therapies, deaths from hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection continue to rise, indicating poor penetrance of medications and care to patients who need them, Dr. Scott Holmberg said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“Deaths in chronic HCV–infected persons, even when grossly under-enumerated on death certificates, far outstrip deaths from 60 other infectious conditions reportable to CDC,” said Dr. Holmberg of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Division of Viral Hepatitis in Atlanta.

Drugs for chronic HCV infection have vastly improved in the past several years, yielding far better rates of sustained viral response (SVR) and high chances of cure after 8-24 weeks of treatment. To see if better antiviral therapies have affected HCV mortality rates, Dr. Holmberg and his associates studied ICD-9 data from Multiple Cause of Death records for all U.S. death certificates between 2003 and 2013. They divided deaths that were linked to HCV or 60 other nationally notifiable infectious diseases by U.S. Census numbers for the same year. They also examined data from the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1055-61), which includes patients presumed to have adequate access to HCV treatment.

Chronic HCV-related deaths climbed from about 12,000 annually in 2003 to more than 19,000 in 2013, said Dr. Holmberg. In contrast, deaths from the 60 other reportable infectious diseases dropped from about 25,000 annually to below 20,000 per year. Annual deaths tied to HIV infection ranked second behind HCV at about 8,800, followed by Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA), hepatitis B virus, tuberculosis, and pneumococcal disease. “This does not include 4,444 adult influenza deaths, but does include 165 childhood influenza deaths in 2013,” Dr. Holmberg noted.

The analysis of the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study revealed a doubling in mortality from chronic HCV infection among patients who should have had adequate access to treatment, according to Dr. Holmberg. For every 100 person-years of observation, about 2.5 people died from consequences of chronic HCV infection in 2007, compared with about 5.5 in 2013, he said. “Hidden mortality from HCV is considerable,” he added. “Only 19% of HCV patients who died had their infection noted anywhere on their death certificates, despite the fact that more than 75% had premortem evidence of liver disease.”

Uptake of sofosbuvir-based regimens more than quintupled in the second quarter of 2015, compared with a year earlier, according to data from Gilead Sciences presented by Dr. Holmberg. But high drug costs have spurred state Medicaid programs and private payers to stipulate many preapproval requirements, he noted. Patients must be drug and alcohol free for at least 6 months, and in many states, must provide evidence of liver scarring from a recent biopsy or FibroScan, which is not always easy to access. “This is often a barrier,” Dr. Holmberg said. “For those in more rural areas, finding a specialist, as required by many state Medicaid offices, can be very difficult.”

And there are even more obstacles. Many clinicians still see HCV as a “benign condition,” and patients often have other urgent health, social, or financial problems, Dr. Holmberg said. The public, for its part, may not prioritize infectious diseases. “These patients lack a strong advocacy group,” he added. “Most are former injection drug users, and the public is often reluctant to help them.”

So what are the measurable results of these barriers? Among about 3.2 million individuals in the United States with chronic HCV infection, only half were ever tested for HCV, 38% received some sort of care related to their infection, 11% were treated, and 6% achieved SVR, Dr. Holmberg and his associates noted in a perspective piece (N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1859-861).

At the same time, the United States faces an emerging epidemic of new HCV infections in nonurban areas among young persons who inject drugs (MMWR. 64;453-8). “This is really a tale of two epidemics,” he added. “Control of the chronic and the acute outbreaks will require a multipronged approach, with interventions along a testing to cure continuum of care.”

Dr. Holmberg and his associates reported their findings at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. The researchers reported no funding sources and had no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Despite better therapies, deaths from hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection continue to rise, indicating poor penetrance of medications and care to patients who need them, Dr. Scott Holmberg said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“Deaths in chronic HCV–infected persons, even when grossly under-enumerated on death certificates, far outstrip deaths from 60 other infectious conditions reportable to CDC,” said Dr. Holmberg of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Division of Viral Hepatitis in Atlanta.

Drugs for chronic HCV infection have vastly improved in the past several years, yielding far better rates of sustained viral response (SVR) and high chances of cure after 8-24 weeks of treatment. To see if better antiviral therapies have affected HCV mortality rates, Dr. Holmberg and his associates studied ICD-9 data from Multiple Cause of Death records for all U.S. death certificates between 2003 and 2013. They divided deaths that were linked to HCV or 60 other nationally notifiable infectious diseases by U.S. Census numbers for the same year. They also examined data from the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1055-61), which includes patients presumed to have adequate access to HCV treatment.

Chronic HCV-related deaths climbed from about 12,000 annually in 2003 to more than 19,000 in 2013, said Dr. Holmberg. In contrast, deaths from the 60 other reportable infectious diseases dropped from about 25,000 annually to below 20,000 per year. Annual deaths tied to HIV infection ranked second behind HCV at about 8,800, followed by Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA), hepatitis B virus, tuberculosis, and pneumococcal disease. “This does not include 4,444 adult influenza deaths, but does include 165 childhood influenza deaths in 2013,” Dr. Holmberg noted.

The analysis of the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study revealed a doubling in mortality from chronic HCV infection among patients who should have had adequate access to treatment, according to Dr. Holmberg. For every 100 person-years of observation, about 2.5 people died from consequences of chronic HCV infection in 2007, compared with about 5.5 in 2013, he said. “Hidden mortality from HCV is considerable,” he added. “Only 19% of HCV patients who died had their infection noted anywhere on their death certificates, despite the fact that more than 75% had premortem evidence of liver disease.”

Uptake of sofosbuvir-based regimens more than quintupled in the second quarter of 2015, compared with a year earlier, according to data from Gilead Sciences presented by Dr. Holmberg. But high drug costs have spurred state Medicaid programs and private payers to stipulate many preapproval requirements, he noted. Patients must be drug and alcohol free for at least 6 months, and in many states, must provide evidence of liver scarring from a recent biopsy or FibroScan, which is not always easy to access. “This is often a barrier,” Dr. Holmberg said. “For those in more rural areas, finding a specialist, as required by many state Medicaid offices, can be very difficult.”

And there are even more obstacles. Many clinicians still see HCV as a “benign condition,” and patients often have other urgent health, social, or financial problems, Dr. Holmberg said. The public, for its part, may not prioritize infectious diseases. “These patients lack a strong advocacy group,” he added. “Most are former injection drug users, and the public is often reluctant to help them.”

So what are the measurable results of these barriers? Among about 3.2 million individuals in the United States with chronic HCV infection, only half were ever tested for HCV, 38% received some sort of care related to their infection, 11% were treated, and 6% achieved SVR, Dr. Holmberg and his associates noted in a perspective piece (N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1859-861).

At the same time, the United States faces an emerging epidemic of new HCV infections in nonurban areas among young persons who inject drugs (MMWR. 64;453-8). “This is really a tale of two epidemics,” he added. “Control of the chronic and the acute outbreaks will require a multipronged approach, with interventions along a testing to cure continuum of care.”

Dr. Holmberg and his associates reported their findings at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. The researchers reported no funding sources and had no financial disclosures.

AT IDWEEK 2015

Key clinical point: Mortality from chronic hepatitis C virus infection continues to rise, despite significant improvements in antiviral therapies.

Major finding: Even with substantial underreporting, in 2013, deaths tied to chronic HCV infection exceeded mortality from 60 other reportable infectious diseases.

Data source: Analysis of 10 years of national death certificate data and 7 years of data from the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study.

Disclosures: The researchers reported no funding sources and made no financial disclosures.