User login

CASE Onset of nausea and headache, and elevated BP, at full term

A 24-year-old woman (G1P0) at 39 2/7 weeks of gestation without significant medical history and with uncomplicated prenatal care presents to labor and delivery reporting uterine contractions. She reports nausea and vomiting, and reports having a severe headache this morning. Blood pressure (BP) is 154/98 mm Hg. Urine dipstick analysis demonstrates absence of protein.

How should this patient be managed?

Although we have gained a greater understanding of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy—most notably, preeclampsia—during the past 15 years, management of these patients can, as evidenced in the case above, be complicated. Providers must respect this disease and be cognizant of the significant maternal, fetal, and neonatal complications that can be associated with hypertension during pregnancy—a leading cause of preterm birth and maternal mortality in the United States.1-3 Initiation of early and aggressive antihypertensive medical therapy, when indicated, plays a key role in preventing catastrophic complications of this disease.

Terminology and classification

Hypertension of pregnancy is classified as:

- chronic hypertension: BP≥140/90 mm Hg prior to pregnancy or prior to 20 weeks of gestation. Patients who have persistently elevated BP 12 weeks after delivery are also in this category.

- preeclampsia–eclampsia: hypertension along with multisystem involvement that occurs after 20 weeks of gestation.

- gestational hypertension: hypertension alone after 20 weeks of gestation; in approximately 15% to 25% of these patients, a diagnosis of preeclampsia will be made as pregnancy progresses.

- chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia: hypertension complicated by development of multisystem involvement during the course of the pregnancy—often a challenging diagnosis, associated with greater perinatal morbidity than either chronic hypertension or preeclampsia alone.

Evaluation of the hypertensive gravida

Although most pregnant patients (approximately 90%) who have a diagnosis of chronic hypertension have primary or essential hypertension, a secondary cause—including thyroid disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and underlying renal disease—might be present and should be sought out. It is important, therefore, to obtain a comprehensive history along with a directed physical examination and appropriate laboratory tests.

Ideally, a patient with chronic hypertension should be evaluated prior to pregnancy, but this rarely occurs. At the initial encounter, the patient should be informed of risks associated with chronic hypertension, as well as receive education on the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia. Obtain a thorough history—not only to evaluate for secondary causes of hypertension or end-organ involvement (eg, kidney disease), but to identify comorbidities (such as pregestational diabetes mellitus). The patient should be instructed to immediately discontinue any teratogenic medication (such as an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin-receptor blocker).

Routine laboratory evaluation

Testing should comprise a chemistry panel to evaluate serum creatinine, electrolytes, and liver enzymes. A 24-hour urine collection for protein excretion and creatinine clearance or a urine protein–creatinine ratio should be obtained to record baseline kidney function.4 (Such testing is important, given that new-onset or worsening proteinuria is a manifestation of superimposed preeclampsia.) All pregnant patients with chronic hypertension also should have a complete blood count, including a platelet count, and an early screen for gestational diabetes.

Depending on what information is obtained from the history and physical examination, renal ultrasonography and any of several laboratory tests can be ordered, including thyroid function, an SLE panel, and vanillylmandelic acid/metanephrines. If the patient has a history of severe hypertension for greater than 5 years, is older than 40 years, or has cardiac symptoms, baseline electrocardio-graphy or echocardiography, or both, are recommended.

Clinical manifestations of chronic hypertension during pregnancy include5:

- in the mother: accelerated hypertension, with resulting target-organ damage involving heart, brain, and kidneys

- in the fetus: placental abruption, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and fetal death.

What should treatment seek to accomplish?

The goal of antihypertensive medication during pregnancy is to reduce maternal risk of stroke, congestive heart failure, renal failure, and severe hypertension. No convincing evidence exists that antihypertensive medications decrease the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia, preterm birth, placental abruption, or perinatal death.

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), antihypertensive medication is not indicated in patients with uncomplicated chronic hypertension unless systolic BP is ≥ 160 mm Hg or diastolic BP is ≥ 105 mm Hg.3 The goal is to maintain systolic BP at 120–160 mm Hg and diastolic BP at 80–105 mm Hg. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends treatment of hypertension when systolic BP is ≥ 150 mm Hg or diastolic BP is ≥ 100 mm Hg.6 In patients with end-organ disease (chronic renal or cardiac disease) ACOG recommends treatment with an antihypertensive when systolic BP is >140 mm Hg or diastolic BP is >90 mm Hg.

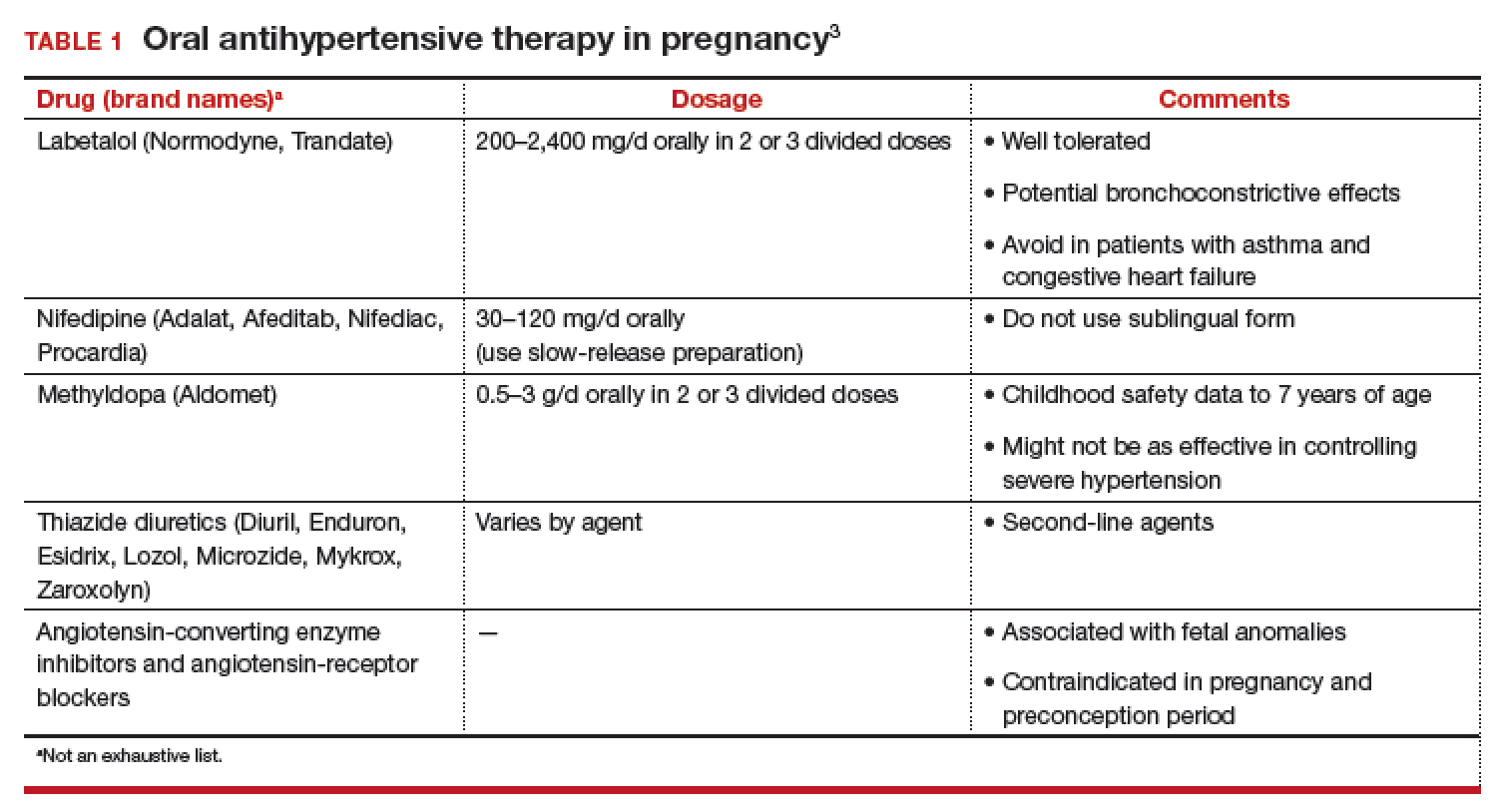

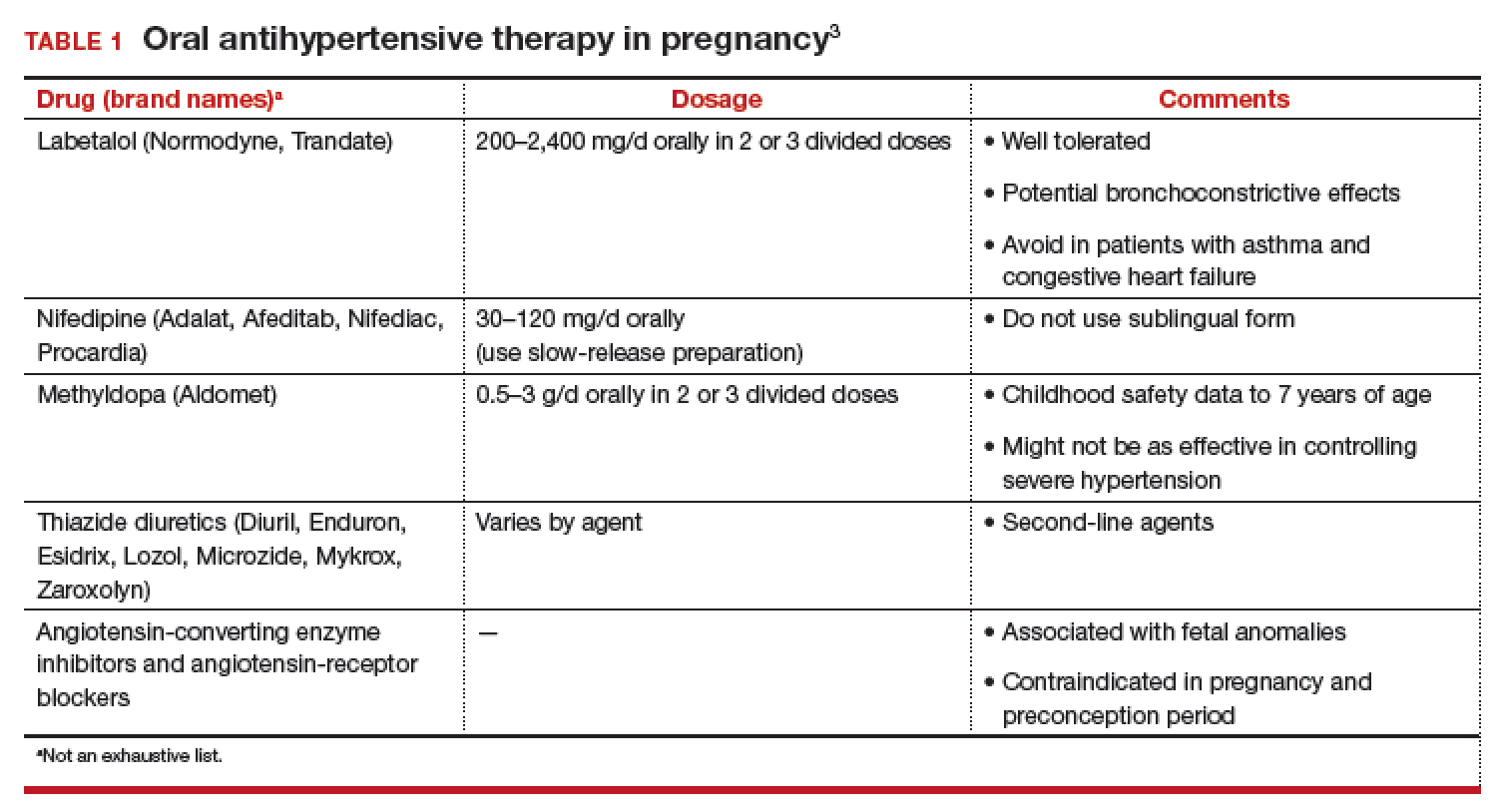

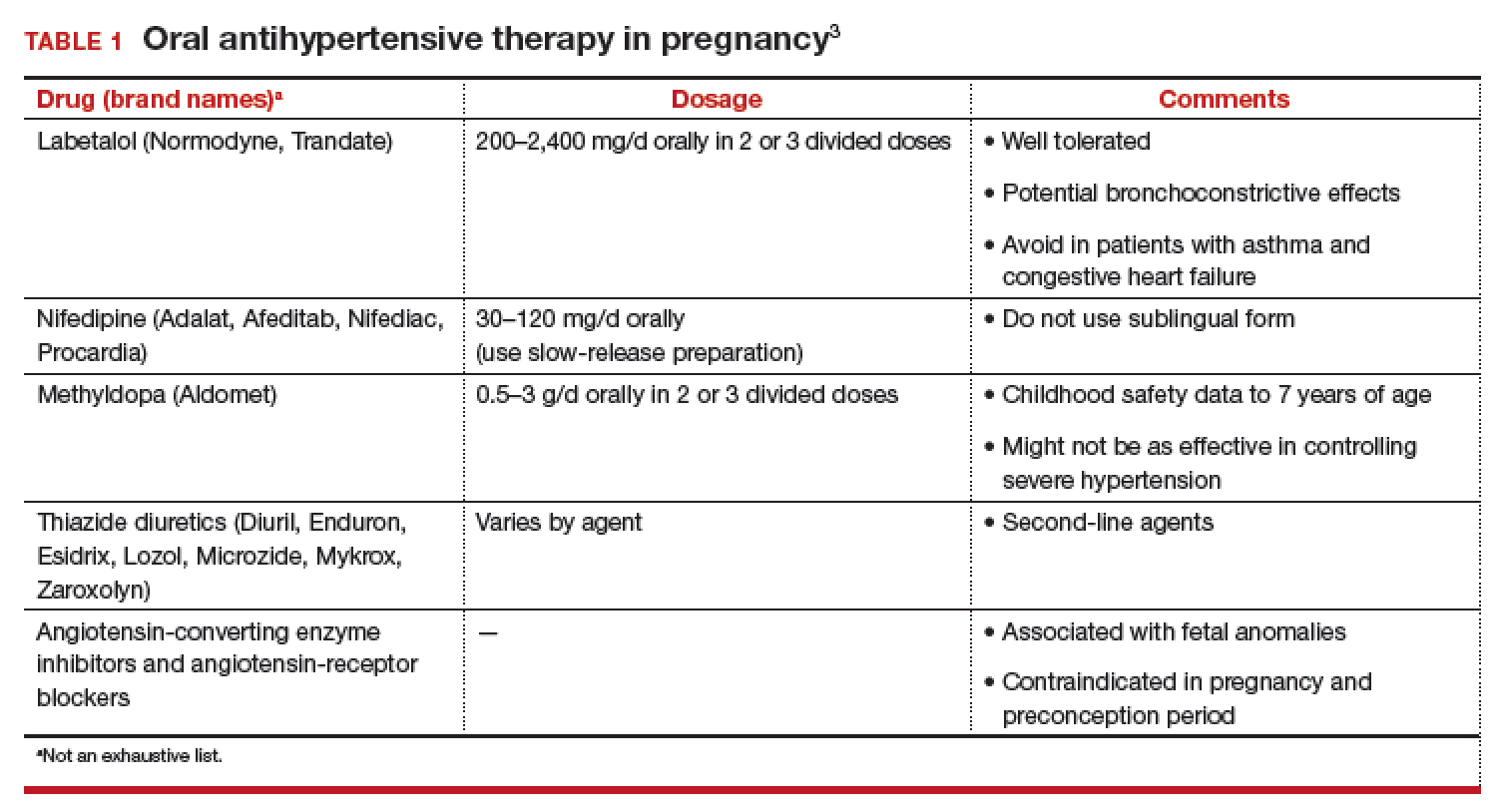

First-line antihypertensives consideredsafe during pregnancy are methyldopa, labetalol, and nifedipine. Thiazide diuretics, although considered second-line agents, may be used during pregnancy—especially if BP is adequately controlled prior to pregnancy. Again, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers are contraindicated during pregnancy (TABLE 1).3

Continuing care in chronic hypertension

Given the maternal and fetal consequences of chronic hypertension, it is recommended that a hypertensive patient be followed closely as an outpatient; in fact, it is advisablethat she check her BP at least twice daily. Beginning at 24 weeks of gestation, serial ultrasonography should be performed every 4 to 6 weeks to evaluate interval fetal growth. Twice-weekly antepartum testing should begin at 32 to 34 weeks of gestation.

During the course of the pregnancy, the chronically hypertensive patient should be observed closely for development of superimposed preeclampsia. If she does not develop preeclampsia or fetal growth restriction, and has no other pregnancy complications that necessitate early delivery, 3 recommendations regarding timing of delivery apply7:

- If the patient is not taking antihypertensive medication, delivery should occur at 38 to 39 6/7 weeks of gestation

- If hypertension is controlled with medication, delivery is recommended at 37 to 39 6/7 weeks of gestation.

- If the patient has severe hypertension that is difficult to control, delivery might be advisable as early as 36 weeks of gestation.

Be vigilant for maternal complications (including cardiac compromise, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, hypertensive encephalopathy, and worsening renal disease) and fetal complications (such as placental abruption, fetal growth restriction, and fetal death). If any of these occur, management must be tailored and individualized accordingly. Study results have demonstrated that superimposed preeclampsia occurs in 20% to 30% of patients who have underlying mild chronic hypertension. This increases to 50% in women with underlying severe hypertension.8

Antihypertensive medication is the mainstay of treatment for severely elevated blood pressure (BP). To avoid fetal heart rate decelerations and possible emergent cesarean delivery, however, do not decrease BP too quickly or lower to values that might compromise perfusion to the fetus. The BP goal should be 140-155 mm Hg (systolic) and 90-105 mm Hg (diastolic). A

Be prepared for eclampsia, which is unpredictable and can occur in patients without symptoms or severely elevated BP and even postpartum in patients in whom the diagnosis of preeclampsia was never made prior to delivery. The response to eclamptic seizure includes administering magnesium sulfate, which is the approved initial therapy for an eclamptic seizure. A

Make algorithms for acute treatment of severe hypertension and eclampsia readily available or posted in labor and delivery units and in the emergency department. C

Counsel high-risk patients about the potential benefit of low-dosage aspirin to prevent preeclampsia. A

Strength of recommendation:

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The complex challenge of managing preeclampsia

Chronic hypertension is not the only risk factor for preeclampsia; others include nulliparity, history of preeclampsia, multifetal gestation, underlying renal disease, SLE, antiphospolipid syndrome, thyroid disease, and pregestational diabetes. Furthermore, preeclampsia has a bimodal age distribution, occurring more often in adolescent pregnancies and women of advanced maternal age. Risk is also increased in the presence of abnormal levels of various serum analytes or biochemical markers, such as a low level of pregnancy-associated plasma protein A or estriol or an elevated level of maternal serum α-fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotropin, or inhibin—findings that might reflect abnormal placentation.9

In fact, the findings of most studies that have looked at the pathophysiology of preeclampsia appear to show that several noteworthy pathophysiologic changes are evident in early pregnancy10,11:

- incomplete trophoblastic invasion of spiral arteries

- retention of thick-walled, muscular arteries

- decreased placental perfusion

- early placental hypoxia

- placental release of factors that lead to endothelial dysfunction and endothelial damage.

Ultimately, vasoconstriction becomes evident, which leads to clinical manifestations of the disorder. In addition, there is an increase in the level of thromboxane (a vasoconstrictor and platelet aggregator), compared to the level of prostacyclin (a vasodilator).

ACOG revises nomenclature, provides recommendations

The considerable expansion of knowledge about preeclampsia over the past 10 to 15 years has not translated to better outcomes. In 2012, ACOG, in response to troubling observations about the condition (see “ACOG finds compelling motivation to boost understanding, management of preeclampsia,”), created a Task Force to investigate hypertension in pregnancy.

Findings and recommendations of the Task Force were published in November 2013,3 and have been endorsed and supported by professional organizations, including the American Academy of Neurology, American Society of Hypertension, Preeclampsia Foundation, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. A major premise of the Task Force that has had a direct impact on recommendations for management of preeclampsia is that the condition is a progressive and dynamic process that involves multiple organ systems and is not specifically confined to the antepartum period.

The nomenclature of mild preeclampsia and severe preeclampsia was changed in the Task Force report to preeclampsia without severe features and preeclampsia with severe features. Preeclampsia without severe features is diagnosed when a patient has:

- systolic BP ≥ 140 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mm Hg (measured twice at least 4 hours apart)

- proteinuria, defined as a 24-hour urine collection of ≥ 300 mg of protein or a urine protein–creatinine ratio of 0.3.

If a patient has elevated BP by those criteria, plus any of several laboratory indicators of multisystem involvement (platelet count, <100 × 103/μL; serum creatinine level, >1.1 mg/dL; doubling in the serum creatinine concentration; liver transaminase concentrations twice normal) or other findings (pulmonary edema, visual disturbance, headaches), she has preeclampsia with severe features. A diagnosis of preeclampsia without severe features is upgraded to preeclampsia with severe features if systolic BP increases to >160 mm Hgor diastolic BP increases to >110 mm Hg (determined by 2 measurements 4 hours apart) or if “severe”-range BP occurs with such rapidity that acute antihypertensive medication is required.

- Incidence of preeclampsia in the United States has increased by 25% over the past 2 decades

- Etiology remains unclear

- Leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality

- Risk factor for future cardiovascular disease and metabolic disease in women

- Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are major contributors to prematurity

- New best-practice recommendations are urgently needed to guide clinicians in the care of women with all forms of preeclampsia and hypertension during pregnancy

- Improved patient education and counseling strategies are needed to convey, more effectively, the dangers of preeclampsia and hypertension during pregnancy

Reference

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. November 2013. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Task-Force-and-Work-Group-Reports/Hypertension-in-Pregnancy. Accessed August 8, 2018.

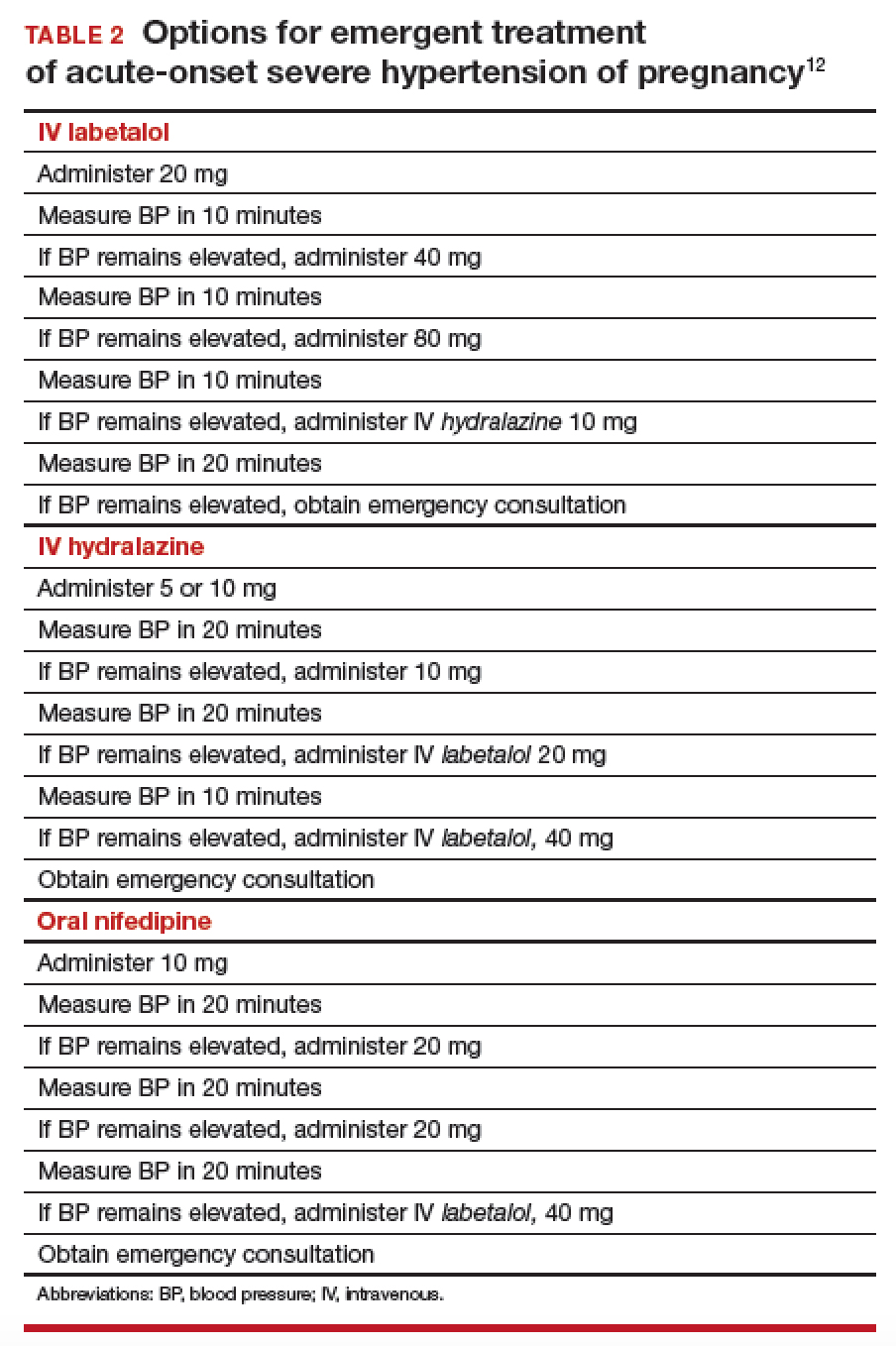

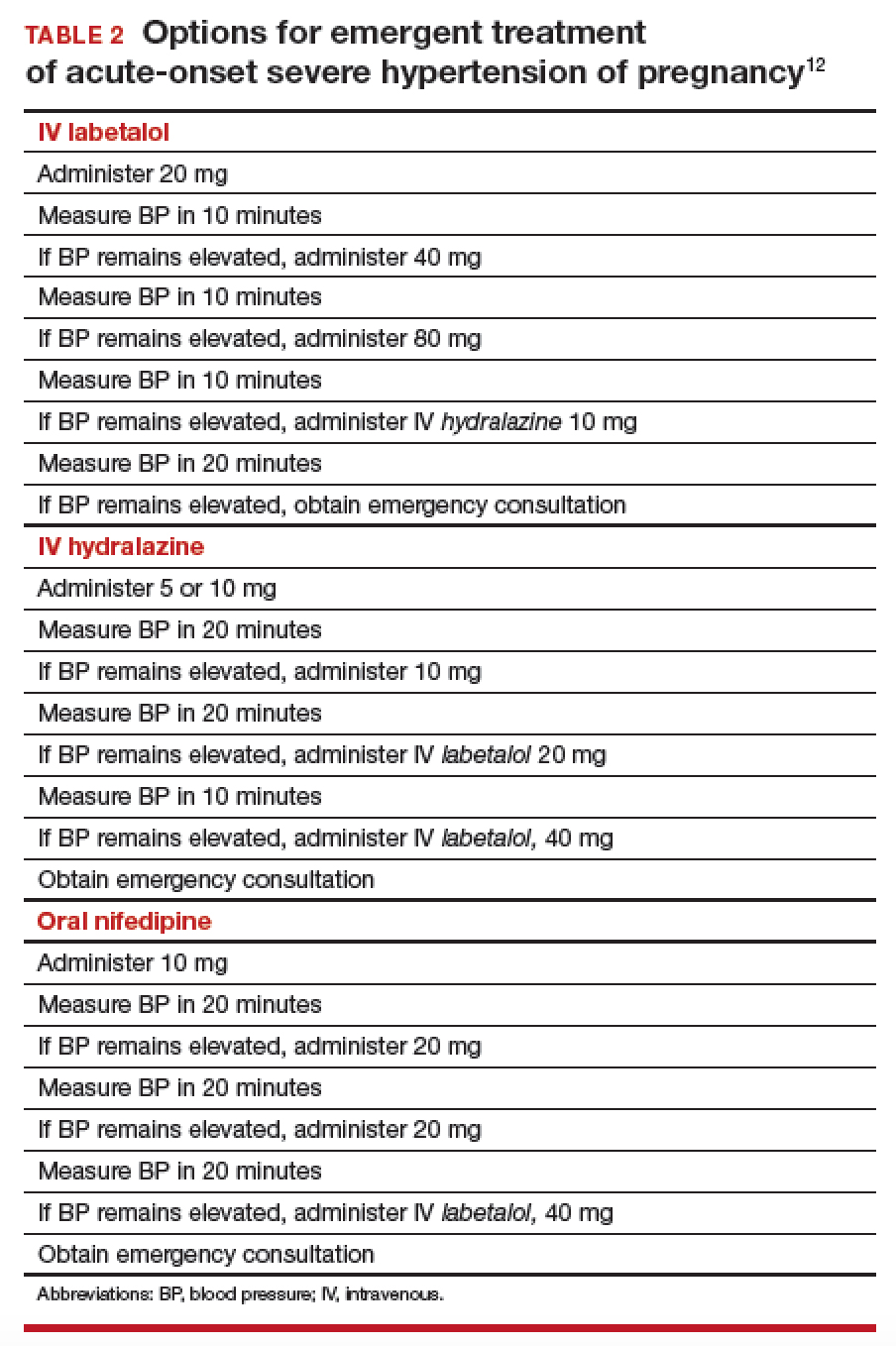

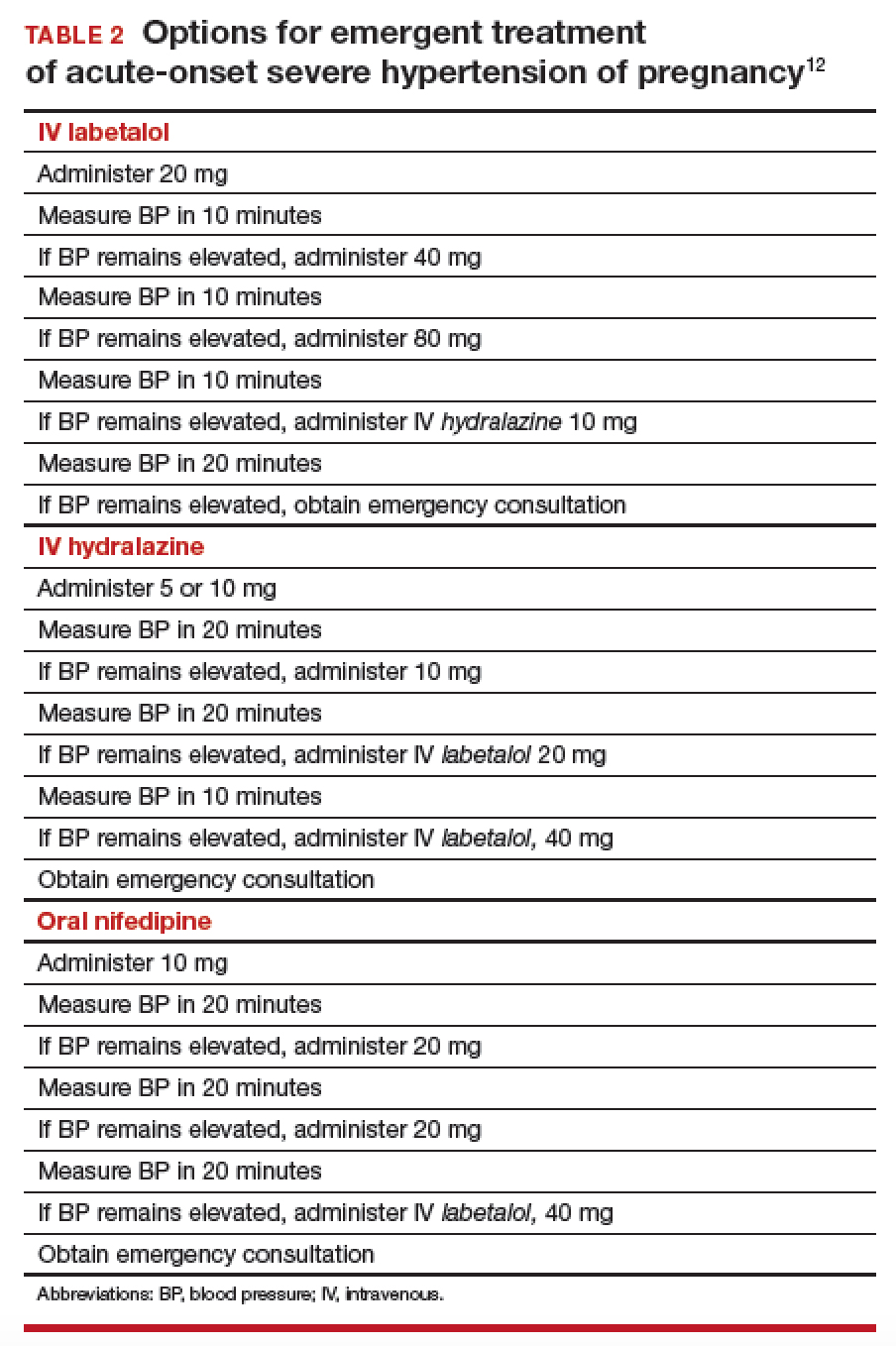

Pharmacotherapy for hypertensive emergency

Acute BP control with intravenous (IV) labetalol or hydralazine or oral nifedipine is recommended when a patient has a hypertensive emergency, defined as acute-onset severe hypertension that persists for ≥ 15 minutes (TABLE 2).12 The goal of management is not to completely normalize BP but to lower BP to the range of 140 to 155 mm Hg (systolic) and 90 to 105 mm Hg (diastolic). Of all proposed interventions, these agents are likely the most effective in preventing a maternal cerebrovascular or cardiovascular event. (Note: Labetalol is contraindicated in patients with severe asthma and in the setting of acute cocaine or methamphetamine intoxication. Hydralazine can cause tachycardia.)13,14

Once a diagnosis of preeclampsia with severe features or superimposed preeclampsia with severe features is made, the patient should remain hospitalized until delivery. If either of these diagnoses is made at ≥ 34 weeks of gestation, there is no reason to prolong pregnancy. Rather, the patient should be given prophylactic magnesium sulfate to prevent seizures and delivery should be accomplished.15,16 Earlier than 36 6/7 weeks of gestation, consider a late preterm course of corticosteroids; however, do not delay delivery in this situation.17

Planning for delivery

Route of delivery depends on customary obstetric indications. Before 34 weeks of gestation, corticosteroids, magnesium sulfate, and prolonging the pregnancy until 34 weeks of gestation are recommended. If, at any time, maternal or fetal condition deteriorates, delivery should be accomplished regardless of gestational age. If the patient is unwilling to accept the risks of expectant management of preeclampsia with severe features remote from term, delivery is indicated.18,19 If delivery is not likely to occur, magnesium sulfate can be discontinued after the patient has received a second dose of corticosteroids, with the plan to resume magnesium sulfate if she develops signs of worsening preeclampsia or eclampsia, or once the plan for delivery is made.

In patients who have either gestational hypertension or preeclampsia without severe features, the recommendation is to accomplish delivery no later than 37 weeks of gestation. While the patient is being expectantly managed, close maternal and fetal surveillance are necessary, comprising serial assessment of maternal symptoms and fetal movement; serial BP measurement (twice weekly); and weekly measurement of the platelet count, serum creatinine, and liver enzymes. At 34 weeks of gestation, conventional antepartum testing should begin. Again, if there is deterioration of the maternal or fetal condition, the patient should be hospitalized and delivery should be accomplished according to the recommendations above.3

Seizure management

If a patient has a tonic–clonic seizure consistent with eclampsia, management should be as follows:

- Preserve the airway and immediately tilt the head forward to prevent aspiration.

- If the patient is not receiving magnesium sulfate, immediately administer a loading dose of 4-6 g IV or 10 mg intramuscularly if IV access has not been established.20

- If the patient is already receiving magnesium sulfate, administer a loading dose of 2 g IV over 5 minutes.

- If the patient continues to have seizure activity, administer anticonvulsant medication(lorazepam, diazepam, midazolam, or phenytoin).

Eclamptic seizures are usually self-limited, lasting no longer than 1 or 2 minutes. Regrettably, these seizures are unpredictable and contribute significantly to maternal morbidity and mortality.21,22 A maternal seizure causes a significant interruption in the oxygen pathway to the fetus, with resultant late decelerations, prolonged decelerations, or bradycardia.

Resist the temptation to perform emergent cesarean delivery when eclamptic seizure occurs; rather, allow time for fetal recovery and then proceed with delivery in a controlled fashion. In many circumstances, the patient can undergo vaginal delivery after an eclamptic seizure. Keep in mind that the differential diagnosis of new-onset seizure in pregnancy includes cerebral pathology, such as a bleeding arteriovenous malformation or ruptured aneurysm. Therefore, brain-imaging studies might be indicated, especially in patients who have focal neurologic deficits, or who have seizures either while receiving magnesium sulfate or 48 to 72 hours after delivery.

Preeclampsia postpartum

More recent studies have demonstrated that preeclampsia can be exacerbated after delivery or might even present initially postpartum.23,24 In all women in whom gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or superimposed preeclampsia is diagnosed, therefore, recommendations are that BP be monitored in the hospital or on an outpatient basis for at least 72 hours postpartum and again 7 to 10 days after delivery. For all women postpartum, the recommendation is that discharge instructions 1) include information about signs and symptoms of preeclampsia and 2) emphasize the importance of promptly reporting such developments to providers.25 Remember: Sequelae of preeclampsia have been reported as late as 4 to 6 weeks postpartum.

Magnesium sulfate is recommended when a patient presents postpartum with new-onset hypertension associated with headache or blurred vision, or with preeclampsia with severe hypertension. Because nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be associated with elevated BP, these medications should be replaced by other analgesics in women with hypertension that persists for more than 1 day postpartum.

Prevention of preeclampsia

Given the significant maternal, fetal, and neonatal complications associated with preeclampsia, a number of studies have sought to determine ways in which this condition can be prevented. Currently, although no interventions appear to prevent preeclampsia in all patients, significant strides have been made in prevention for high-risk patients. Specifically, beginning low-dosage aspirin (most commonly, 81 mg/d, beginning at less than 16 weeks of gestation) has been shown to mitigate—although not eliminate—risk in patients with a history of preeclampsia and those who have chronic hypertension, multifetal gestation, pregestational diabetes, renal disease, SLE, or antiphospholipid syndrome.26,27Aspirin appears to act by preferentially blocking production of thromboxane, thus reducing the vasoconstrictive properties of this hormone.

Summing up

Hypertensive disorders during pregnancy are associated with significant morbidity and mortality for mother, fetus, and newborn. Preeclampsia, specifically, is recognized as a dynamic and progressive disease that has the potential to involve multiple organ systems, might present for the first time after delivery, and might be associated with long-term risk of hypertension, heart disease, stroke, and venous thromboembolism.28,29

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Callaghan WM, Mackay AP, Berg CJ. Identification of severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations, United States, 1991-2003. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 199:133.e1-e8.

- Kuklina EV, Ayala C, Callaghan WM. Hypertensive disorders and severe obstetric morbidity in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1299-1306.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. November 2013. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Task-Force-and-Work-Group-Reports/Hypertension-in-Pregnancy. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Wheeler TL 2nd, Blackhurst DW, Dellinger EH, Ramsey PS. Usage of spot urine protein to creatinine ratios in the evaluation of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:465.e1-e4.

- Bramham K, Parnell B, Nelson-Piercy C, Seed PT, Poston L, Chappell LL. Chronic hypertension and pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g2301.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. CG107, August 2010. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg107. Accessed August 27, 2018. Last updated January 2011.

- Spong CY, Mercer BM, D'Alton M, et al. Timing of indicated late-preterm and early-term birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:323-333.

- Sibai BM. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(2):369-377.

- Dugoff L; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. First- and second-trimester maternal serum markers or aneuploidy and adverse obstetric outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:1052-1061.

- Brosens I, Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Romero R. The "great obstetrical syndromes" are associated with disorders of deep placentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:193-201.

- Huppertz B. Placental origins of preeclampsia: challenging the current hypothesis. Hypertension. 2008;51:970-975.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice; El-Sayed YY, Borders AE. Committee Opinion Number 692. Emergent therapy for acute-onset, severe hypertension during pregnancy and the postpartum period; April 2017. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/co692.pdf?dmc=1. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Hollander JE. The management of cocaine-associated myocardial ischemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1267-1272.

- Ghuran A, Nolan J. Recreational drug misuse: issues for the cardiologist. Heart. 2000;83:627-633.

- Altman D, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. Do women with pre-eclampsia and their babies, benefit from magnesium sulphate? The Magpie Trial: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1877-1890.

- Sibai BM. Magnesium sulfate prophylaxis in preeclampsia: lessons learned from recent trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1520-1526.

- Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Thom EA, Blackwell SC, et al. Antenatal betamethasone for women at risk for late preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1311-1320.

- Publications Committee, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Sibai BM. Evaluation and management of severe preeclampsia before 34 weeks' gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:191-198.

- Norwitz E, Funai E. Expectant management of severe preeclampsia remote from term: hope for the best, but expect the worst. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:209-212.

- Gordon R, Magee LA, Payne B, et al. Magnesium sulphate for the management of preeclampsia and eclampsia in low and middle income countries: a systematic review of tested dosing regimens. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36(2):154-163.

- Sibai BM. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):402-410.

- Liu S, Joseph KS, Liston, RM, et al; Maternal Health Study Group of Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System (Public Health Agency of Canada). Incidence, risk factors, and associated complications of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):987-994.

- Yancey LM, Withers E, Bakes K, Abbot J. Postpartum preeclampsia: emergency department presentation and management. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:380-384.

- Sibai BM. Etiology and management of postpartum hypertension-preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:470-475.

- You WB, Wolf MS, Bailey SC, Grobman WA. Improving patient understanding of preeclampsia: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:431.e1-e5.

- Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O'Connor E, et al. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:695-703.

- Roberge S, Nicolaides K, Demers S, Hyett J, Chaillet N, Bujold E. The role of aspirin dose on the prevention of preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):110-120.e6.

- Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335:974-986.

- McDonald SD, Malinowski A, Zhou Q, et al. Cardiovascular sequelae of preeclampsia/eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Am Heart J. 2008;156:918-930.

CASE Onset of nausea and headache, and elevated BP, at full term

A 24-year-old woman (G1P0) at 39 2/7 weeks of gestation without significant medical history and with uncomplicated prenatal care presents to labor and delivery reporting uterine contractions. She reports nausea and vomiting, and reports having a severe headache this morning. Blood pressure (BP) is 154/98 mm Hg. Urine dipstick analysis demonstrates absence of protein.

How should this patient be managed?

Although we have gained a greater understanding of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy—most notably, preeclampsia—during the past 15 years, management of these patients can, as evidenced in the case above, be complicated. Providers must respect this disease and be cognizant of the significant maternal, fetal, and neonatal complications that can be associated with hypertension during pregnancy—a leading cause of preterm birth and maternal mortality in the United States.1-3 Initiation of early and aggressive antihypertensive medical therapy, when indicated, plays a key role in preventing catastrophic complications of this disease.

Terminology and classification

Hypertension of pregnancy is classified as:

- chronic hypertension: BP≥140/90 mm Hg prior to pregnancy or prior to 20 weeks of gestation. Patients who have persistently elevated BP 12 weeks after delivery are also in this category.

- preeclampsia–eclampsia: hypertension along with multisystem involvement that occurs after 20 weeks of gestation.

- gestational hypertension: hypertension alone after 20 weeks of gestation; in approximately 15% to 25% of these patients, a diagnosis of preeclampsia will be made as pregnancy progresses.

- chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia: hypertension complicated by development of multisystem involvement during the course of the pregnancy—often a challenging diagnosis, associated with greater perinatal morbidity than either chronic hypertension or preeclampsia alone.

Evaluation of the hypertensive gravida

Although most pregnant patients (approximately 90%) who have a diagnosis of chronic hypertension have primary or essential hypertension, a secondary cause—including thyroid disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and underlying renal disease—might be present and should be sought out. It is important, therefore, to obtain a comprehensive history along with a directed physical examination and appropriate laboratory tests.

Ideally, a patient with chronic hypertension should be evaluated prior to pregnancy, but this rarely occurs. At the initial encounter, the patient should be informed of risks associated with chronic hypertension, as well as receive education on the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia. Obtain a thorough history—not only to evaluate for secondary causes of hypertension or end-organ involvement (eg, kidney disease), but to identify comorbidities (such as pregestational diabetes mellitus). The patient should be instructed to immediately discontinue any teratogenic medication (such as an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin-receptor blocker).

Routine laboratory evaluation

Testing should comprise a chemistry panel to evaluate serum creatinine, electrolytes, and liver enzymes. A 24-hour urine collection for protein excretion and creatinine clearance or a urine protein–creatinine ratio should be obtained to record baseline kidney function.4 (Such testing is important, given that new-onset or worsening proteinuria is a manifestation of superimposed preeclampsia.) All pregnant patients with chronic hypertension also should have a complete blood count, including a platelet count, and an early screen for gestational diabetes.

Depending on what information is obtained from the history and physical examination, renal ultrasonography and any of several laboratory tests can be ordered, including thyroid function, an SLE panel, and vanillylmandelic acid/metanephrines. If the patient has a history of severe hypertension for greater than 5 years, is older than 40 years, or has cardiac symptoms, baseline electrocardio-graphy or echocardiography, or both, are recommended.

Clinical manifestations of chronic hypertension during pregnancy include5:

- in the mother: accelerated hypertension, with resulting target-organ damage involving heart, brain, and kidneys

- in the fetus: placental abruption, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and fetal death.

What should treatment seek to accomplish?

The goal of antihypertensive medication during pregnancy is to reduce maternal risk of stroke, congestive heart failure, renal failure, and severe hypertension. No convincing evidence exists that antihypertensive medications decrease the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia, preterm birth, placental abruption, or perinatal death.

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), antihypertensive medication is not indicated in patients with uncomplicated chronic hypertension unless systolic BP is ≥ 160 mm Hg or diastolic BP is ≥ 105 mm Hg.3 The goal is to maintain systolic BP at 120–160 mm Hg and diastolic BP at 80–105 mm Hg. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends treatment of hypertension when systolic BP is ≥ 150 mm Hg or diastolic BP is ≥ 100 mm Hg.6 In patients with end-organ disease (chronic renal or cardiac disease) ACOG recommends treatment with an antihypertensive when systolic BP is >140 mm Hg or diastolic BP is >90 mm Hg.

First-line antihypertensives consideredsafe during pregnancy are methyldopa, labetalol, and nifedipine. Thiazide diuretics, although considered second-line agents, may be used during pregnancy—especially if BP is adequately controlled prior to pregnancy. Again, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers are contraindicated during pregnancy (TABLE 1).3

Continuing care in chronic hypertension

Given the maternal and fetal consequences of chronic hypertension, it is recommended that a hypertensive patient be followed closely as an outpatient; in fact, it is advisablethat she check her BP at least twice daily. Beginning at 24 weeks of gestation, serial ultrasonography should be performed every 4 to 6 weeks to evaluate interval fetal growth. Twice-weekly antepartum testing should begin at 32 to 34 weeks of gestation.

During the course of the pregnancy, the chronically hypertensive patient should be observed closely for development of superimposed preeclampsia. If she does not develop preeclampsia or fetal growth restriction, and has no other pregnancy complications that necessitate early delivery, 3 recommendations regarding timing of delivery apply7:

- If the patient is not taking antihypertensive medication, delivery should occur at 38 to 39 6/7 weeks of gestation

- If hypertension is controlled with medication, delivery is recommended at 37 to 39 6/7 weeks of gestation.

- If the patient has severe hypertension that is difficult to control, delivery might be advisable as early as 36 weeks of gestation.

Be vigilant for maternal complications (including cardiac compromise, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, hypertensive encephalopathy, and worsening renal disease) and fetal complications (such as placental abruption, fetal growth restriction, and fetal death). If any of these occur, management must be tailored and individualized accordingly. Study results have demonstrated that superimposed preeclampsia occurs in 20% to 30% of patients who have underlying mild chronic hypertension. This increases to 50% in women with underlying severe hypertension.8

Antihypertensive medication is the mainstay of treatment for severely elevated blood pressure (BP). To avoid fetal heart rate decelerations and possible emergent cesarean delivery, however, do not decrease BP too quickly or lower to values that might compromise perfusion to the fetus. The BP goal should be 140-155 mm Hg (systolic) and 90-105 mm Hg (diastolic). A

Be prepared for eclampsia, which is unpredictable and can occur in patients without symptoms or severely elevated BP and even postpartum in patients in whom the diagnosis of preeclampsia was never made prior to delivery. The response to eclamptic seizure includes administering magnesium sulfate, which is the approved initial therapy for an eclamptic seizure. A

Make algorithms for acute treatment of severe hypertension and eclampsia readily available or posted in labor and delivery units and in the emergency department. C

Counsel high-risk patients about the potential benefit of low-dosage aspirin to prevent preeclampsia. A

Strength of recommendation:

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The complex challenge of managing preeclampsia

Chronic hypertension is not the only risk factor for preeclampsia; others include nulliparity, history of preeclampsia, multifetal gestation, underlying renal disease, SLE, antiphospolipid syndrome, thyroid disease, and pregestational diabetes. Furthermore, preeclampsia has a bimodal age distribution, occurring more often in adolescent pregnancies and women of advanced maternal age. Risk is also increased in the presence of abnormal levels of various serum analytes or biochemical markers, such as a low level of pregnancy-associated plasma protein A or estriol or an elevated level of maternal serum α-fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotropin, or inhibin—findings that might reflect abnormal placentation.9

In fact, the findings of most studies that have looked at the pathophysiology of preeclampsia appear to show that several noteworthy pathophysiologic changes are evident in early pregnancy10,11:

- incomplete trophoblastic invasion of spiral arteries

- retention of thick-walled, muscular arteries

- decreased placental perfusion

- early placental hypoxia

- placental release of factors that lead to endothelial dysfunction and endothelial damage.

Ultimately, vasoconstriction becomes evident, which leads to clinical manifestations of the disorder. In addition, there is an increase in the level of thromboxane (a vasoconstrictor and platelet aggregator), compared to the level of prostacyclin (a vasodilator).

ACOG revises nomenclature, provides recommendations

The considerable expansion of knowledge about preeclampsia over the past 10 to 15 years has not translated to better outcomes. In 2012, ACOG, in response to troubling observations about the condition (see “ACOG finds compelling motivation to boost understanding, management of preeclampsia,”), created a Task Force to investigate hypertension in pregnancy.

Findings and recommendations of the Task Force were published in November 2013,3 and have been endorsed and supported by professional organizations, including the American Academy of Neurology, American Society of Hypertension, Preeclampsia Foundation, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. A major premise of the Task Force that has had a direct impact on recommendations for management of preeclampsia is that the condition is a progressive and dynamic process that involves multiple organ systems and is not specifically confined to the antepartum period.

The nomenclature of mild preeclampsia and severe preeclampsia was changed in the Task Force report to preeclampsia without severe features and preeclampsia with severe features. Preeclampsia without severe features is diagnosed when a patient has:

- systolic BP ≥ 140 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mm Hg (measured twice at least 4 hours apart)

- proteinuria, defined as a 24-hour urine collection of ≥ 300 mg of protein or a urine protein–creatinine ratio of 0.3.

If a patient has elevated BP by those criteria, plus any of several laboratory indicators of multisystem involvement (platelet count, <100 × 103/μL; serum creatinine level, >1.1 mg/dL; doubling in the serum creatinine concentration; liver transaminase concentrations twice normal) or other findings (pulmonary edema, visual disturbance, headaches), she has preeclampsia with severe features. A diagnosis of preeclampsia without severe features is upgraded to preeclampsia with severe features if systolic BP increases to >160 mm Hgor diastolic BP increases to >110 mm Hg (determined by 2 measurements 4 hours apart) or if “severe”-range BP occurs with such rapidity that acute antihypertensive medication is required.

- Incidence of preeclampsia in the United States has increased by 25% over the past 2 decades

- Etiology remains unclear

- Leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality

- Risk factor for future cardiovascular disease and metabolic disease in women

- Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are major contributors to prematurity

- New best-practice recommendations are urgently needed to guide clinicians in the care of women with all forms of preeclampsia and hypertension during pregnancy

- Improved patient education and counseling strategies are needed to convey, more effectively, the dangers of preeclampsia and hypertension during pregnancy

Reference

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. November 2013. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Task-Force-and-Work-Group-Reports/Hypertension-in-Pregnancy. Accessed August 8, 2018.

Pharmacotherapy for hypertensive emergency

Acute BP control with intravenous (IV) labetalol or hydralazine or oral nifedipine is recommended when a patient has a hypertensive emergency, defined as acute-onset severe hypertension that persists for ≥ 15 minutes (TABLE 2).12 The goal of management is not to completely normalize BP but to lower BP to the range of 140 to 155 mm Hg (systolic) and 90 to 105 mm Hg (diastolic). Of all proposed interventions, these agents are likely the most effective in preventing a maternal cerebrovascular or cardiovascular event. (Note: Labetalol is contraindicated in patients with severe asthma and in the setting of acute cocaine or methamphetamine intoxication. Hydralazine can cause tachycardia.)13,14

Once a diagnosis of preeclampsia with severe features or superimposed preeclampsia with severe features is made, the patient should remain hospitalized until delivery. If either of these diagnoses is made at ≥ 34 weeks of gestation, there is no reason to prolong pregnancy. Rather, the patient should be given prophylactic magnesium sulfate to prevent seizures and delivery should be accomplished.15,16 Earlier than 36 6/7 weeks of gestation, consider a late preterm course of corticosteroids; however, do not delay delivery in this situation.17

Planning for delivery

Route of delivery depends on customary obstetric indications. Before 34 weeks of gestation, corticosteroids, magnesium sulfate, and prolonging the pregnancy until 34 weeks of gestation are recommended. If, at any time, maternal or fetal condition deteriorates, delivery should be accomplished regardless of gestational age. If the patient is unwilling to accept the risks of expectant management of preeclampsia with severe features remote from term, delivery is indicated.18,19 If delivery is not likely to occur, magnesium sulfate can be discontinued after the patient has received a second dose of corticosteroids, with the plan to resume magnesium sulfate if she develops signs of worsening preeclampsia or eclampsia, or once the plan for delivery is made.

In patients who have either gestational hypertension or preeclampsia without severe features, the recommendation is to accomplish delivery no later than 37 weeks of gestation. While the patient is being expectantly managed, close maternal and fetal surveillance are necessary, comprising serial assessment of maternal symptoms and fetal movement; serial BP measurement (twice weekly); and weekly measurement of the platelet count, serum creatinine, and liver enzymes. At 34 weeks of gestation, conventional antepartum testing should begin. Again, if there is deterioration of the maternal or fetal condition, the patient should be hospitalized and delivery should be accomplished according to the recommendations above.3

Seizure management

If a patient has a tonic–clonic seizure consistent with eclampsia, management should be as follows:

- Preserve the airway and immediately tilt the head forward to prevent aspiration.

- If the patient is not receiving magnesium sulfate, immediately administer a loading dose of 4-6 g IV or 10 mg intramuscularly if IV access has not been established.20

- If the patient is already receiving magnesium sulfate, administer a loading dose of 2 g IV over 5 minutes.

- If the patient continues to have seizure activity, administer anticonvulsant medication(lorazepam, diazepam, midazolam, or phenytoin).

Eclamptic seizures are usually self-limited, lasting no longer than 1 or 2 minutes. Regrettably, these seizures are unpredictable and contribute significantly to maternal morbidity and mortality.21,22 A maternal seizure causes a significant interruption in the oxygen pathway to the fetus, with resultant late decelerations, prolonged decelerations, or bradycardia.

Resist the temptation to perform emergent cesarean delivery when eclamptic seizure occurs; rather, allow time for fetal recovery and then proceed with delivery in a controlled fashion. In many circumstances, the patient can undergo vaginal delivery after an eclamptic seizure. Keep in mind that the differential diagnosis of new-onset seizure in pregnancy includes cerebral pathology, such as a bleeding arteriovenous malformation or ruptured aneurysm. Therefore, brain-imaging studies might be indicated, especially in patients who have focal neurologic deficits, or who have seizures either while receiving magnesium sulfate or 48 to 72 hours after delivery.

Preeclampsia postpartum

More recent studies have demonstrated that preeclampsia can be exacerbated after delivery or might even present initially postpartum.23,24 In all women in whom gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or superimposed preeclampsia is diagnosed, therefore, recommendations are that BP be monitored in the hospital or on an outpatient basis for at least 72 hours postpartum and again 7 to 10 days after delivery. For all women postpartum, the recommendation is that discharge instructions 1) include information about signs and symptoms of preeclampsia and 2) emphasize the importance of promptly reporting such developments to providers.25 Remember: Sequelae of preeclampsia have been reported as late as 4 to 6 weeks postpartum.

Magnesium sulfate is recommended when a patient presents postpartum with new-onset hypertension associated with headache or blurred vision, or with preeclampsia with severe hypertension. Because nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be associated with elevated BP, these medications should be replaced by other analgesics in women with hypertension that persists for more than 1 day postpartum.

Prevention of preeclampsia

Given the significant maternal, fetal, and neonatal complications associated with preeclampsia, a number of studies have sought to determine ways in which this condition can be prevented. Currently, although no interventions appear to prevent preeclampsia in all patients, significant strides have been made in prevention for high-risk patients. Specifically, beginning low-dosage aspirin (most commonly, 81 mg/d, beginning at less than 16 weeks of gestation) has been shown to mitigate—although not eliminate—risk in patients with a history of preeclampsia and those who have chronic hypertension, multifetal gestation, pregestational diabetes, renal disease, SLE, or antiphospholipid syndrome.26,27Aspirin appears to act by preferentially blocking production of thromboxane, thus reducing the vasoconstrictive properties of this hormone.

Summing up

Hypertensive disorders during pregnancy are associated with significant morbidity and mortality for mother, fetus, and newborn. Preeclampsia, specifically, is recognized as a dynamic and progressive disease that has the potential to involve multiple organ systems, might present for the first time after delivery, and might be associated with long-term risk of hypertension, heart disease, stroke, and venous thromboembolism.28,29

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE Onset of nausea and headache, and elevated BP, at full term

A 24-year-old woman (G1P0) at 39 2/7 weeks of gestation without significant medical history and with uncomplicated prenatal care presents to labor and delivery reporting uterine contractions. She reports nausea and vomiting, and reports having a severe headache this morning. Blood pressure (BP) is 154/98 mm Hg. Urine dipstick analysis demonstrates absence of protein.

How should this patient be managed?

Although we have gained a greater understanding of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy—most notably, preeclampsia—during the past 15 years, management of these patients can, as evidenced in the case above, be complicated. Providers must respect this disease and be cognizant of the significant maternal, fetal, and neonatal complications that can be associated with hypertension during pregnancy—a leading cause of preterm birth and maternal mortality in the United States.1-3 Initiation of early and aggressive antihypertensive medical therapy, when indicated, plays a key role in preventing catastrophic complications of this disease.

Terminology and classification

Hypertension of pregnancy is classified as:

- chronic hypertension: BP≥140/90 mm Hg prior to pregnancy or prior to 20 weeks of gestation. Patients who have persistently elevated BP 12 weeks after delivery are also in this category.

- preeclampsia–eclampsia: hypertension along with multisystem involvement that occurs after 20 weeks of gestation.

- gestational hypertension: hypertension alone after 20 weeks of gestation; in approximately 15% to 25% of these patients, a diagnosis of preeclampsia will be made as pregnancy progresses.

- chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia: hypertension complicated by development of multisystem involvement during the course of the pregnancy—often a challenging diagnosis, associated with greater perinatal morbidity than either chronic hypertension or preeclampsia alone.

Evaluation of the hypertensive gravida

Although most pregnant patients (approximately 90%) who have a diagnosis of chronic hypertension have primary or essential hypertension, a secondary cause—including thyroid disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and underlying renal disease—might be present and should be sought out. It is important, therefore, to obtain a comprehensive history along with a directed physical examination and appropriate laboratory tests.

Ideally, a patient with chronic hypertension should be evaluated prior to pregnancy, but this rarely occurs. At the initial encounter, the patient should be informed of risks associated with chronic hypertension, as well as receive education on the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia. Obtain a thorough history—not only to evaluate for secondary causes of hypertension or end-organ involvement (eg, kidney disease), but to identify comorbidities (such as pregestational diabetes mellitus). The patient should be instructed to immediately discontinue any teratogenic medication (such as an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin-receptor blocker).

Routine laboratory evaluation

Testing should comprise a chemistry panel to evaluate serum creatinine, electrolytes, and liver enzymes. A 24-hour urine collection for protein excretion and creatinine clearance or a urine protein–creatinine ratio should be obtained to record baseline kidney function.4 (Such testing is important, given that new-onset or worsening proteinuria is a manifestation of superimposed preeclampsia.) All pregnant patients with chronic hypertension also should have a complete blood count, including a platelet count, and an early screen for gestational diabetes.

Depending on what information is obtained from the history and physical examination, renal ultrasonography and any of several laboratory tests can be ordered, including thyroid function, an SLE panel, and vanillylmandelic acid/metanephrines. If the patient has a history of severe hypertension for greater than 5 years, is older than 40 years, or has cardiac symptoms, baseline electrocardio-graphy or echocardiography, or both, are recommended.

Clinical manifestations of chronic hypertension during pregnancy include5:

- in the mother: accelerated hypertension, with resulting target-organ damage involving heart, brain, and kidneys

- in the fetus: placental abruption, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and fetal death.

What should treatment seek to accomplish?

The goal of antihypertensive medication during pregnancy is to reduce maternal risk of stroke, congestive heart failure, renal failure, and severe hypertension. No convincing evidence exists that antihypertensive medications decrease the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia, preterm birth, placental abruption, or perinatal death.

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), antihypertensive medication is not indicated in patients with uncomplicated chronic hypertension unless systolic BP is ≥ 160 mm Hg or diastolic BP is ≥ 105 mm Hg.3 The goal is to maintain systolic BP at 120–160 mm Hg and diastolic BP at 80–105 mm Hg. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends treatment of hypertension when systolic BP is ≥ 150 mm Hg or diastolic BP is ≥ 100 mm Hg.6 In patients with end-organ disease (chronic renal or cardiac disease) ACOG recommends treatment with an antihypertensive when systolic BP is >140 mm Hg or diastolic BP is >90 mm Hg.

First-line antihypertensives consideredsafe during pregnancy are methyldopa, labetalol, and nifedipine. Thiazide diuretics, although considered second-line agents, may be used during pregnancy—especially if BP is adequately controlled prior to pregnancy. Again, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers are contraindicated during pregnancy (TABLE 1).3

Continuing care in chronic hypertension

Given the maternal and fetal consequences of chronic hypertension, it is recommended that a hypertensive patient be followed closely as an outpatient; in fact, it is advisablethat she check her BP at least twice daily. Beginning at 24 weeks of gestation, serial ultrasonography should be performed every 4 to 6 weeks to evaluate interval fetal growth. Twice-weekly antepartum testing should begin at 32 to 34 weeks of gestation.

During the course of the pregnancy, the chronically hypertensive patient should be observed closely for development of superimposed preeclampsia. If she does not develop preeclampsia or fetal growth restriction, and has no other pregnancy complications that necessitate early delivery, 3 recommendations regarding timing of delivery apply7:

- If the patient is not taking antihypertensive medication, delivery should occur at 38 to 39 6/7 weeks of gestation

- If hypertension is controlled with medication, delivery is recommended at 37 to 39 6/7 weeks of gestation.

- If the patient has severe hypertension that is difficult to control, delivery might be advisable as early as 36 weeks of gestation.

Be vigilant for maternal complications (including cardiac compromise, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, hypertensive encephalopathy, and worsening renal disease) and fetal complications (such as placental abruption, fetal growth restriction, and fetal death). If any of these occur, management must be tailored and individualized accordingly. Study results have demonstrated that superimposed preeclampsia occurs in 20% to 30% of patients who have underlying mild chronic hypertension. This increases to 50% in women with underlying severe hypertension.8

Antihypertensive medication is the mainstay of treatment for severely elevated blood pressure (BP). To avoid fetal heart rate decelerations and possible emergent cesarean delivery, however, do not decrease BP too quickly or lower to values that might compromise perfusion to the fetus. The BP goal should be 140-155 mm Hg (systolic) and 90-105 mm Hg (diastolic). A

Be prepared for eclampsia, which is unpredictable and can occur in patients without symptoms or severely elevated BP and even postpartum in patients in whom the diagnosis of preeclampsia was never made prior to delivery. The response to eclamptic seizure includes administering magnesium sulfate, which is the approved initial therapy for an eclamptic seizure. A

Make algorithms for acute treatment of severe hypertension and eclampsia readily available or posted in labor and delivery units and in the emergency department. C

Counsel high-risk patients about the potential benefit of low-dosage aspirin to prevent preeclampsia. A

Strength of recommendation:

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The complex challenge of managing preeclampsia

Chronic hypertension is not the only risk factor for preeclampsia; others include nulliparity, history of preeclampsia, multifetal gestation, underlying renal disease, SLE, antiphospolipid syndrome, thyroid disease, and pregestational diabetes. Furthermore, preeclampsia has a bimodal age distribution, occurring more often in adolescent pregnancies and women of advanced maternal age. Risk is also increased in the presence of abnormal levels of various serum analytes or biochemical markers, such as a low level of pregnancy-associated plasma protein A or estriol or an elevated level of maternal serum α-fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotropin, or inhibin—findings that might reflect abnormal placentation.9

In fact, the findings of most studies that have looked at the pathophysiology of preeclampsia appear to show that several noteworthy pathophysiologic changes are evident in early pregnancy10,11:

- incomplete trophoblastic invasion of spiral arteries

- retention of thick-walled, muscular arteries

- decreased placental perfusion

- early placental hypoxia

- placental release of factors that lead to endothelial dysfunction and endothelial damage.

Ultimately, vasoconstriction becomes evident, which leads to clinical manifestations of the disorder. In addition, there is an increase in the level of thromboxane (a vasoconstrictor and platelet aggregator), compared to the level of prostacyclin (a vasodilator).

ACOG revises nomenclature, provides recommendations

The considerable expansion of knowledge about preeclampsia over the past 10 to 15 years has not translated to better outcomes. In 2012, ACOG, in response to troubling observations about the condition (see “ACOG finds compelling motivation to boost understanding, management of preeclampsia,”), created a Task Force to investigate hypertension in pregnancy.

Findings and recommendations of the Task Force were published in November 2013,3 and have been endorsed and supported by professional organizations, including the American Academy of Neurology, American Society of Hypertension, Preeclampsia Foundation, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. A major premise of the Task Force that has had a direct impact on recommendations for management of preeclampsia is that the condition is a progressive and dynamic process that involves multiple organ systems and is not specifically confined to the antepartum period.

The nomenclature of mild preeclampsia and severe preeclampsia was changed in the Task Force report to preeclampsia without severe features and preeclampsia with severe features. Preeclampsia without severe features is diagnosed when a patient has:

- systolic BP ≥ 140 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mm Hg (measured twice at least 4 hours apart)

- proteinuria, defined as a 24-hour urine collection of ≥ 300 mg of protein or a urine protein–creatinine ratio of 0.3.

If a patient has elevated BP by those criteria, plus any of several laboratory indicators of multisystem involvement (platelet count, <100 × 103/μL; serum creatinine level, >1.1 mg/dL; doubling in the serum creatinine concentration; liver transaminase concentrations twice normal) or other findings (pulmonary edema, visual disturbance, headaches), she has preeclampsia with severe features. A diagnosis of preeclampsia without severe features is upgraded to preeclampsia with severe features if systolic BP increases to >160 mm Hgor diastolic BP increases to >110 mm Hg (determined by 2 measurements 4 hours apart) or if “severe”-range BP occurs with such rapidity that acute antihypertensive medication is required.

- Incidence of preeclampsia in the United States has increased by 25% over the past 2 decades

- Etiology remains unclear

- Leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality

- Risk factor for future cardiovascular disease and metabolic disease in women

- Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are major contributors to prematurity

- New best-practice recommendations are urgently needed to guide clinicians in the care of women with all forms of preeclampsia and hypertension during pregnancy

- Improved patient education and counseling strategies are needed to convey, more effectively, the dangers of preeclampsia and hypertension during pregnancy

Reference

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. November 2013. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Task-Force-and-Work-Group-Reports/Hypertension-in-Pregnancy. Accessed August 8, 2018.

Pharmacotherapy for hypertensive emergency

Acute BP control with intravenous (IV) labetalol or hydralazine or oral nifedipine is recommended when a patient has a hypertensive emergency, defined as acute-onset severe hypertension that persists for ≥ 15 minutes (TABLE 2).12 The goal of management is not to completely normalize BP but to lower BP to the range of 140 to 155 mm Hg (systolic) and 90 to 105 mm Hg (diastolic). Of all proposed interventions, these agents are likely the most effective in preventing a maternal cerebrovascular or cardiovascular event. (Note: Labetalol is contraindicated in patients with severe asthma and in the setting of acute cocaine or methamphetamine intoxication. Hydralazine can cause tachycardia.)13,14

Once a diagnosis of preeclampsia with severe features or superimposed preeclampsia with severe features is made, the patient should remain hospitalized until delivery. If either of these diagnoses is made at ≥ 34 weeks of gestation, there is no reason to prolong pregnancy. Rather, the patient should be given prophylactic magnesium sulfate to prevent seizures and delivery should be accomplished.15,16 Earlier than 36 6/7 weeks of gestation, consider a late preterm course of corticosteroids; however, do not delay delivery in this situation.17

Planning for delivery

Route of delivery depends on customary obstetric indications. Before 34 weeks of gestation, corticosteroids, magnesium sulfate, and prolonging the pregnancy until 34 weeks of gestation are recommended. If, at any time, maternal or fetal condition deteriorates, delivery should be accomplished regardless of gestational age. If the patient is unwilling to accept the risks of expectant management of preeclampsia with severe features remote from term, delivery is indicated.18,19 If delivery is not likely to occur, magnesium sulfate can be discontinued after the patient has received a second dose of corticosteroids, with the plan to resume magnesium sulfate if she develops signs of worsening preeclampsia or eclampsia, or once the plan for delivery is made.

In patients who have either gestational hypertension or preeclampsia without severe features, the recommendation is to accomplish delivery no later than 37 weeks of gestation. While the patient is being expectantly managed, close maternal and fetal surveillance are necessary, comprising serial assessment of maternal symptoms and fetal movement; serial BP measurement (twice weekly); and weekly measurement of the platelet count, serum creatinine, and liver enzymes. At 34 weeks of gestation, conventional antepartum testing should begin. Again, if there is deterioration of the maternal or fetal condition, the patient should be hospitalized and delivery should be accomplished according to the recommendations above.3

Seizure management

If a patient has a tonic–clonic seizure consistent with eclampsia, management should be as follows:

- Preserve the airway and immediately tilt the head forward to prevent aspiration.

- If the patient is not receiving magnesium sulfate, immediately administer a loading dose of 4-6 g IV or 10 mg intramuscularly if IV access has not been established.20

- If the patient is already receiving magnesium sulfate, administer a loading dose of 2 g IV over 5 minutes.

- If the patient continues to have seizure activity, administer anticonvulsant medication(lorazepam, diazepam, midazolam, or phenytoin).

Eclamptic seizures are usually self-limited, lasting no longer than 1 or 2 minutes. Regrettably, these seizures are unpredictable and contribute significantly to maternal morbidity and mortality.21,22 A maternal seizure causes a significant interruption in the oxygen pathway to the fetus, with resultant late decelerations, prolonged decelerations, or bradycardia.

Resist the temptation to perform emergent cesarean delivery when eclamptic seizure occurs; rather, allow time for fetal recovery and then proceed with delivery in a controlled fashion. In many circumstances, the patient can undergo vaginal delivery after an eclamptic seizure. Keep in mind that the differential diagnosis of new-onset seizure in pregnancy includes cerebral pathology, such as a bleeding arteriovenous malformation or ruptured aneurysm. Therefore, brain-imaging studies might be indicated, especially in patients who have focal neurologic deficits, or who have seizures either while receiving magnesium sulfate or 48 to 72 hours after delivery.

Preeclampsia postpartum

More recent studies have demonstrated that preeclampsia can be exacerbated after delivery or might even present initially postpartum.23,24 In all women in whom gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, or superimposed preeclampsia is diagnosed, therefore, recommendations are that BP be monitored in the hospital or on an outpatient basis for at least 72 hours postpartum and again 7 to 10 days after delivery. For all women postpartum, the recommendation is that discharge instructions 1) include information about signs and symptoms of preeclampsia and 2) emphasize the importance of promptly reporting such developments to providers.25 Remember: Sequelae of preeclampsia have been reported as late as 4 to 6 weeks postpartum.

Magnesium sulfate is recommended when a patient presents postpartum with new-onset hypertension associated with headache or blurred vision, or with preeclampsia with severe hypertension. Because nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be associated with elevated BP, these medications should be replaced by other analgesics in women with hypertension that persists for more than 1 day postpartum.

Prevention of preeclampsia

Given the significant maternal, fetal, and neonatal complications associated with preeclampsia, a number of studies have sought to determine ways in which this condition can be prevented. Currently, although no interventions appear to prevent preeclampsia in all patients, significant strides have been made in prevention for high-risk patients. Specifically, beginning low-dosage aspirin (most commonly, 81 mg/d, beginning at less than 16 weeks of gestation) has been shown to mitigate—although not eliminate—risk in patients with a history of preeclampsia and those who have chronic hypertension, multifetal gestation, pregestational diabetes, renal disease, SLE, or antiphospholipid syndrome.26,27Aspirin appears to act by preferentially blocking production of thromboxane, thus reducing the vasoconstrictive properties of this hormone.

Summing up

Hypertensive disorders during pregnancy are associated with significant morbidity and mortality for mother, fetus, and newborn. Preeclampsia, specifically, is recognized as a dynamic and progressive disease that has the potential to involve multiple organ systems, might present for the first time after delivery, and might be associated with long-term risk of hypertension, heart disease, stroke, and venous thromboembolism.28,29

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Callaghan WM, Mackay AP, Berg CJ. Identification of severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations, United States, 1991-2003. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 199:133.e1-e8.

- Kuklina EV, Ayala C, Callaghan WM. Hypertensive disorders and severe obstetric morbidity in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1299-1306.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. November 2013. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Task-Force-and-Work-Group-Reports/Hypertension-in-Pregnancy. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Wheeler TL 2nd, Blackhurst DW, Dellinger EH, Ramsey PS. Usage of spot urine protein to creatinine ratios in the evaluation of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:465.e1-e4.

- Bramham K, Parnell B, Nelson-Piercy C, Seed PT, Poston L, Chappell LL. Chronic hypertension and pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g2301.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. CG107, August 2010. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg107. Accessed August 27, 2018. Last updated January 2011.

- Spong CY, Mercer BM, D'Alton M, et al. Timing of indicated late-preterm and early-term birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:323-333.

- Sibai BM. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(2):369-377.

- Dugoff L; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. First- and second-trimester maternal serum markers or aneuploidy and adverse obstetric outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:1052-1061.

- Brosens I, Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Romero R. The "great obstetrical syndromes" are associated with disorders of deep placentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:193-201.

- Huppertz B. Placental origins of preeclampsia: challenging the current hypothesis. Hypertension. 2008;51:970-975.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice; El-Sayed YY, Borders AE. Committee Opinion Number 692. Emergent therapy for acute-onset, severe hypertension during pregnancy and the postpartum period; April 2017. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/co692.pdf?dmc=1. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Hollander JE. The management of cocaine-associated myocardial ischemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1267-1272.

- Ghuran A, Nolan J. Recreational drug misuse: issues for the cardiologist. Heart. 2000;83:627-633.

- Altman D, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. Do women with pre-eclampsia and their babies, benefit from magnesium sulphate? The Magpie Trial: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1877-1890.

- Sibai BM. Magnesium sulfate prophylaxis in preeclampsia: lessons learned from recent trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1520-1526.

- Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Thom EA, Blackwell SC, et al. Antenatal betamethasone for women at risk for late preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1311-1320.

- Publications Committee, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Sibai BM. Evaluation and management of severe preeclampsia before 34 weeks' gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:191-198.

- Norwitz E, Funai E. Expectant management of severe preeclampsia remote from term: hope for the best, but expect the worst. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:209-212.

- Gordon R, Magee LA, Payne B, et al. Magnesium sulphate for the management of preeclampsia and eclampsia in low and middle income countries: a systematic review of tested dosing regimens. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36(2):154-163.

- Sibai BM. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):402-410.

- Liu S, Joseph KS, Liston, RM, et al; Maternal Health Study Group of Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System (Public Health Agency of Canada). Incidence, risk factors, and associated complications of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):987-994.

- Yancey LM, Withers E, Bakes K, Abbot J. Postpartum preeclampsia: emergency department presentation and management. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:380-384.

- Sibai BM. Etiology and management of postpartum hypertension-preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:470-475.

- You WB, Wolf MS, Bailey SC, Grobman WA. Improving patient understanding of preeclampsia: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:431.e1-e5.

- Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O'Connor E, et al. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:695-703.

- Roberge S, Nicolaides K, Demers S, Hyett J, Chaillet N, Bujold E. The role of aspirin dose on the prevention of preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):110-120.e6.

- Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335:974-986.

- McDonald SD, Malinowski A, Zhou Q, et al. Cardiovascular sequelae of preeclampsia/eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Am Heart J. 2008;156:918-930.

- Callaghan WM, Mackay AP, Berg CJ. Identification of severe maternal morbidity during delivery hospitalizations, United States, 1991-2003. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008; 199:133.e1-e8.

- Kuklina EV, Ayala C, Callaghan WM. Hypertensive disorders and severe obstetric morbidity in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1299-1306.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. November 2013. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Task-Force-and-Work-Group-Reports/Hypertension-in-Pregnancy. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Wheeler TL 2nd, Blackhurst DW, Dellinger EH, Ramsey PS. Usage of spot urine protein to creatinine ratios in the evaluation of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:465.e1-e4.

- Bramham K, Parnell B, Nelson-Piercy C, Seed PT, Poston L, Chappell LL. Chronic hypertension and pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g2301.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. CG107, August 2010. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg107. Accessed August 27, 2018. Last updated January 2011.

- Spong CY, Mercer BM, D'Alton M, et al. Timing of indicated late-preterm and early-term birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:323-333.

- Sibai BM. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(2):369-377.

- Dugoff L; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. First- and second-trimester maternal serum markers or aneuploidy and adverse obstetric outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:1052-1061.

- Brosens I, Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Romero R. The "great obstetrical syndromes" are associated with disorders of deep placentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:193-201.

- Huppertz B. Placental origins of preeclampsia: challenging the current hypothesis. Hypertension. 2008;51:970-975.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice; El-Sayed YY, Borders AE. Committee Opinion Number 692. Emergent therapy for acute-onset, severe hypertension during pregnancy and the postpartum period; April 2017. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/co692.pdf?dmc=1. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Hollander JE. The management of cocaine-associated myocardial ischemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1267-1272.

- Ghuran A, Nolan J. Recreational drug misuse: issues for the cardiologist. Heart. 2000;83:627-633.

- Altman D, Carroli G, Duley L, et al. Do women with pre-eclampsia and their babies, benefit from magnesium sulphate? The Magpie Trial: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1877-1890.

- Sibai BM. Magnesium sulfate prophylaxis in preeclampsia: lessons learned from recent trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1520-1526.

- Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Thom EA, Blackwell SC, et al. Antenatal betamethasone for women at risk for late preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1311-1320.

- Publications Committee, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Sibai BM. Evaluation and management of severe preeclampsia before 34 weeks' gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:191-198.

- Norwitz E, Funai E. Expectant management of severe preeclampsia remote from term: hope for the best, but expect the worst. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199:209-212.

- Gordon R, Magee LA, Payne B, et al. Magnesium sulphate for the management of preeclampsia and eclampsia in low and middle income countries: a systematic review of tested dosing regimens. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36(2):154-163.

- Sibai BM. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):402-410.

- Liu S, Joseph KS, Liston, RM, et al; Maternal Health Study Group of Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System (Public Health Agency of Canada). Incidence, risk factors, and associated complications of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):987-994.

- Yancey LM, Withers E, Bakes K, Abbot J. Postpartum preeclampsia: emergency department presentation and management. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:380-384.

- Sibai BM. Etiology and management of postpartum hypertension-preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:470-475.

- You WB, Wolf MS, Bailey SC, Grobman WA. Improving patient understanding of preeclampsia: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:431.e1-e5.

- Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O'Connor E, et al. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:695-703.

- Roberge S, Nicolaides K, Demers S, Hyett J, Chaillet N, Bujold E. The role of aspirin dose on the prevention of preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):110-120.e6.

- Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;335:974-986.

- McDonald SD, Malinowski A, Zhou Q, et al. Cardiovascular sequelae of preeclampsia/eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Am Heart J. 2008;156:918-930.