User login

Over the past 3 decades, the prevalence of overweight and obesity has increased dramatically in the United States. A study published in 2016 showed the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity in 2013–2014 was 35% among men and 40.4% among women.1 It comes as no surprise that increased reliance on inexpensive fast foods coupled with progressively more sedentary lifestyles have been implicated as causative factors.2

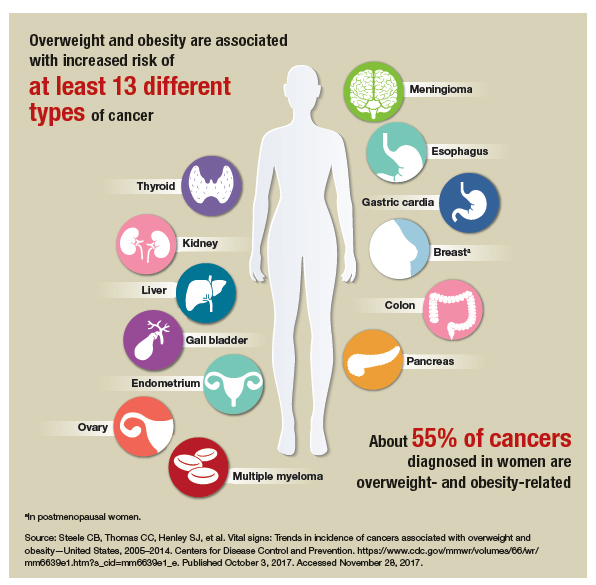

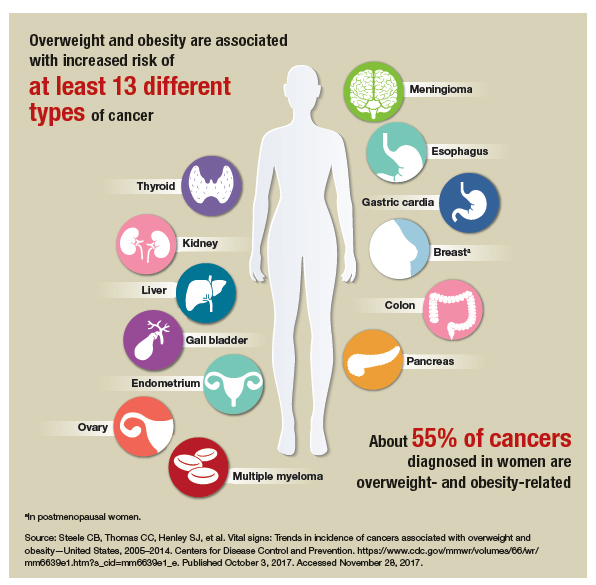

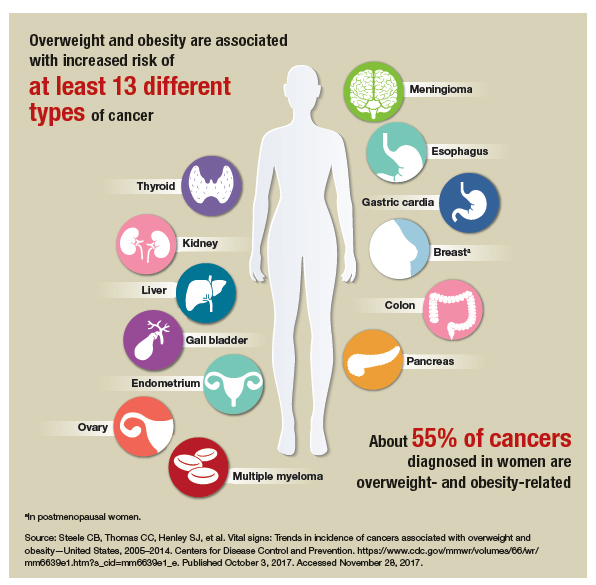

With the rise in obesity also has come an attendant rise in related chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Women who are obese are also at risk for certain women’s health conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome, breast cancer, and endometrial cancer.

It is clear that curbing this public health crisis will require concerted efforts from individuals, clinicians, and policy makers, as well as changes in societal norms.

Linda D. Bradley, MD: I think it is important for us not to lecture our patients. I could list all of the things that patients should or could do to prevent or even reverse disease states, in terms of eating right and exercising, but I think motivational interviewing is a more productive approach to elicit and evoke change (see “Principles and practice of motivational interviewing”). I used to preach to my patients. I would say, “You know, if you stay at this weight, you’re going to get diabetes, you’re going to increase your breast cancer risk, you’re going to have abnormal bleeding, you’re not going to be able to get pregnant,” and so on. It is easy to slip into that in the 7 minutes that you have with your patient, but to me, that is not the right way.

With motivational interviewing, our interactions with patients are shaped by:

- asking

- advising

- assisting

- arranging.

We begin by asking permission: “Do you mind if we talk about your weight?” or “Can we talk about your level of exercise?” Once the patient has granted permission, we ask open-ended questions and use reflective listening: “What I hear you saying is that you are concerned you will not be able to lose the weight,” or “It sounds like you don’t like to exercise, but you are worried about the health consequences of that.”

Utilizing motivational interviewing to help patients identify thoughts and feelings that contribute to unhealthy behaviors--and replacing those thoughts and feelings with new thought patterns that aid in behavior change--has been shown to be an effective and efficient facilitator for change. By incorporating the following principles of motivational interviewing into practice, clinicians can have an important impact on the prevention or management of serious diseases in women1:

- Express empathy and avoid arguments. "I know it has been difficult for you to take the first step to losing weight. That is something that is difficult for a lot of my patients. How can I help you take that first step?"

- Develop discrepancies to help the patient understand the difference between her behavior and her goals. "You have said that you would like to lose some weight. I think you know that exercise would help with that. Why do you think it has been hard for you to start exercising more?"

- Roll with resistance and provide personalized feedback to help the patient find ways to succeed. "What I hear you saying is your work schedule does not allow you time to work out at the gym. What about walking during lunch breaks or taking the stairs instead of the elevator--is that something you think you can commit to doing?"

- Support self-efficacy and elicit self-motivation. "What would you like to see differently about your health? What makes you think you need to change? What happens if you don't change?"

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 423: Motivational interviewing: a tool for behavioral change. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):243-246.

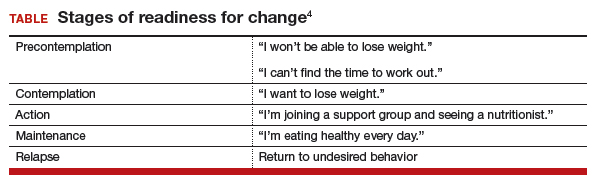

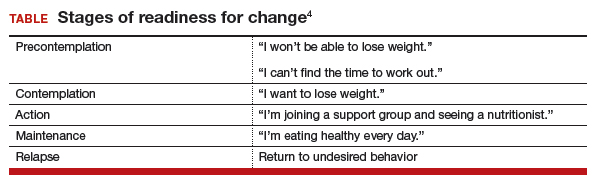

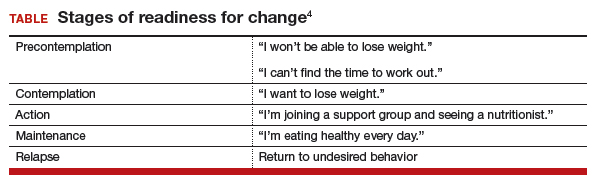

I find these skills useful for addressing anything from smoking to drinking to weight management to excessive shopping—any extreme behavior that is affecting a patient negatively. When a patient is not ready to talk about her clinical problems or make changes, I let her know my door is always open to her and that I have many resources available to help her when she is ready (TABLE).4 In those cases, I might say something like, “I have many patients who really don’t want to talk about this when I first ask them, but I just want you to know, Mrs. Jones, that I want you to succeed and I want you to be healthy. We have a team approach to taking care of all of you, and when you are ready, we are here to help.”

Related article:

2017 Update on fertility: Effects of obesity on reproduction

It is important to provide practical advice to patients—including how much to exercise, the importance of keeping a food journal, and determining a goal for slow, safe weight loss—and provide resources as necessary (such as for Weight Watchers, nutrition, and dieticians). Each day we have more than 30 opportunities to select foods to eat, drink, or purchase. Have a plan and advise your patients do the same. Recommend patients cook their own meals. Suggest weight loss apps. Counsel them to celebrate successes, find a buddy (for social support), practice positive self-talk (positive language), and plan for challenges (travel, parties, working late) and setbacks, which do not need to become a fall. Find an activity or exercise that the patient enjoys and tell them to seek professional help if needed.

Read about how to educate your patients on wellness.

Dr. Bradley: About 86% of the health care dollars spent in the United States are due to chronic diseases, and chronic diseases are the leading cause of death and disability in the country.5 The most common chronic diseases—cardiovascular disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, colon cancer, depression, dementia, cognitive problems, higher rates of fractures—all have been associated, at least in part, with unhealthy food choices and lack of exercise. That applies to breast cancer, too.

The good news is, we can prevent and even reverse disease. As Hippocrates said, let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food. We have all seen success stories where consistent exercise and dietary changes definitely change the paradigm for what the disease state represents. A multiplicity of factors affect poor health—noncompliance, obesity, smoking—but when we begin to make consistent, healthy changes with diet and exercise, this creates a sort of domino effect.

In the book Us! Our Life. Our Health. Our Legacy,1 co-authored by Dr. Bradley and her colleague, Margaret L. McKenzie, MD, the authors highlight the 10 healthiest behaviors to bring about youthfulness and robust health:

- Walk at least 30-45 minutes per day most days of the week.

- Engage in resistance training 2-3 days per week.

- Eat a primarily plant-based diet made up of a variety of whole foods.

- Do not smoke.

- Maintain a waist line that measures less than half your height.

- Drink alcohol only in moderation.

- Get 7-8 hours of sleep most nights.

- Forgive.

- Have gratitude.

- Believe in something greater than yourself.

- Bradley LD, McKenzie ML. Us! Our life. Our health. Our legacy. Las Vegas, Nevada: The Literary Front Publishing Co., LLC; 2016.

Dr. Bradley: I think we need to get to the root cause of these clinical problems and provide the resources and support that patients need to reverse or even prevent these diseases. Clinicians need to become more aware—be an example and a role model. Our patients are watching us as much as we are watching them. Together, we can form good partnerships in order to promote better health.

Dr. Bradley: I think when you are about to be a change agent for your body and become what I call the best version of yourself, you can have these great ideas, but you need to turn those ideas into actions and make them consistent. And we know that is difficult to do, so I do try to have patients write down specific goals, their plan for achieving them, and list the reasons why it is important for them to reach their goals. That gives them something tangible to look at when the going gets tough. It is also important to work into the contract ways to reward positive behaviors when goals are met, and to plan for challenges and setbacks and how to get back on track.

I also encourage patients to document their progress and learn how to make quick adjustments when necessary to get back on track. Another important element involves setting milestones—by what date are you going to reach this goal? Like any other contract, I have my patients date and sign their wellness contracts. I also encourage them to visualize what their new self is going to look like, how they will feel when they reach their goal, what they will wear, and what activities they will engage in.

Related article:

Obesity medicine: How to incorporate it into your practice

Dr. Bradley: I do, but the amount of nutrition education that most of us get in medical school is minimal to nonexistent and not practical. As physicians, we know that food is health, exercise is fitness, and that our patients need both of them. We also know that we did not get this information in school and that our education was more about treating disease than preventing disease. Many of us were not trained in robot surgery either, because it did not exist. So what did we do? We took classes, attended lectures, read books, and learned. We can do the same with wellness. There are many courses around the country. We have to begin to relearn and reteach ourselves about health, nutrition, and exercise and then pass that information on to our patients—be a resource and a guide. We should be able to write a prescription for health as quickly as we can write a prescription for insulin or a statin.

I also bring up portion distortion with my patients. The National Institutes of Health has resources on their website (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational /wecan/eat-right/portion-distortion.html) that include great visuals that show portion sizes 20 years ago and what they are now. For instance, 20 years ago a bagel was 3 inches and 140 calories; today’s bagel is 6 inches and 350 calories (plus whatever toppings are added). I tell that to my patients and then explain how much more exercise is needed to burn off just that 1 bagel.

Related article:

How to help your patients control gestational weight gain

Dr. Bradley: They may not know that term directly, but I think people understand that you have the potential to pass on poor lifestyle and/or health issues related to how things are when you are in utero and later in life. It gets back to letting people know to be healthy in pregnancy and even pre-pregnancy, and that includes one’s emotional state, physical state, and spiritual state. We are what we are in our mother’s womb. Getting the best start in life starts with a healthy mom, healthy dad, and a healthy environment.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, et al. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA.2016;315(21):2284Arial–2291.

- Sturm R, An R. Obesity and economic environments. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(5):337Arial–350.

- Bradley LD, McKenzie ML. Us! Our life. Our health. Our legacy. Las Vegas, Nevada: The Literary Front Publishing Co., LLC; 2016.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 423: Motivational interviewing: a tool for behavioral change. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):243–246.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic disease overview. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm. Updated June 28, 2017. Accessed November 3, 2017.

Over the past 3 decades, the prevalence of overweight and obesity has increased dramatically in the United States. A study published in 2016 showed the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity in 2013–2014 was 35% among men and 40.4% among women.1 It comes as no surprise that increased reliance on inexpensive fast foods coupled with progressively more sedentary lifestyles have been implicated as causative factors.2

With the rise in obesity also has come an attendant rise in related chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Women who are obese are also at risk for certain women’s health conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome, breast cancer, and endometrial cancer.

It is clear that curbing this public health crisis will require concerted efforts from individuals, clinicians, and policy makers, as well as changes in societal norms.

Linda D. Bradley, MD: I think it is important for us not to lecture our patients. I could list all of the things that patients should or could do to prevent or even reverse disease states, in terms of eating right and exercising, but I think motivational interviewing is a more productive approach to elicit and evoke change (see “Principles and practice of motivational interviewing”). I used to preach to my patients. I would say, “You know, if you stay at this weight, you’re going to get diabetes, you’re going to increase your breast cancer risk, you’re going to have abnormal bleeding, you’re not going to be able to get pregnant,” and so on. It is easy to slip into that in the 7 minutes that you have with your patient, but to me, that is not the right way.

With motivational interviewing, our interactions with patients are shaped by:

- asking

- advising

- assisting

- arranging.

We begin by asking permission: “Do you mind if we talk about your weight?” or “Can we talk about your level of exercise?” Once the patient has granted permission, we ask open-ended questions and use reflective listening: “What I hear you saying is that you are concerned you will not be able to lose the weight,” or “It sounds like you don’t like to exercise, but you are worried about the health consequences of that.”

Utilizing motivational interviewing to help patients identify thoughts and feelings that contribute to unhealthy behaviors--and replacing those thoughts and feelings with new thought patterns that aid in behavior change--has been shown to be an effective and efficient facilitator for change. By incorporating the following principles of motivational interviewing into practice, clinicians can have an important impact on the prevention or management of serious diseases in women1:

- Express empathy and avoid arguments. "I know it has been difficult for you to take the first step to losing weight. That is something that is difficult for a lot of my patients. How can I help you take that first step?"

- Develop discrepancies to help the patient understand the difference between her behavior and her goals. "You have said that you would like to lose some weight. I think you know that exercise would help with that. Why do you think it has been hard for you to start exercising more?"

- Roll with resistance and provide personalized feedback to help the patient find ways to succeed. "What I hear you saying is your work schedule does not allow you time to work out at the gym. What about walking during lunch breaks or taking the stairs instead of the elevator--is that something you think you can commit to doing?"

- Support self-efficacy and elicit self-motivation. "What would you like to see differently about your health? What makes you think you need to change? What happens if you don't change?"

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 423: Motivational interviewing: a tool for behavioral change. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):243-246.

I find these skills useful for addressing anything from smoking to drinking to weight management to excessive shopping—any extreme behavior that is affecting a patient negatively. When a patient is not ready to talk about her clinical problems or make changes, I let her know my door is always open to her and that I have many resources available to help her when she is ready (TABLE).4 In those cases, I might say something like, “I have many patients who really don’t want to talk about this when I first ask them, but I just want you to know, Mrs. Jones, that I want you to succeed and I want you to be healthy. We have a team approach to taking care of all of you, and when you are ready, we are here to help.”

Related article:

2017 Update on fertility: Effects of obesity on reproduction

It is important to provide practical advice to patients—including how much to exercise, the importance of keeping a food journal, and determining a goal for slow, safe weight loss—and provide resources as necessary (such as for Weight Watchers, nutrition, and dieticians). Each day we have more than 30 opportunities to select foods to eat, drink, or purchase. Have a plan and advise your patients do the same. Recommend patients cook their own meals. Suggest weight loss apps. Counsel them to celebrate successes, find a buddy (for social support), practice positive self-talk (positive language), and plan for challenges (travel, parties, working late) and setbacks, which do not need to become a fall. Find an activity or exercise that the patient enjoys and tell them to seek professional help if needed.

Read about how to educate your patients on wellness.

Dr. Bradley: About 86% of the health care dollars spent in the United States are due to chronic diseases, and chronic diseases are the leading cause of death and disability in the country.5 The most common chronic diseases—cardiovascular disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, colon cancer, depression, dementia, cognitive problems, higher rates of fractures—all have been associated, at least in part, with unhealthy food choices and lack of exercise. That applies to breast cancer, too.

The good news is, we can prevent and even reverse disease. As Hippocrates said, let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food. We have all seen success stories where consistent exercise and dietary changes definitely change the paradigm for what the disease state represents. A multiplicity of factors affect poor health—noncompliance, obesity, smoking—but when we begin to make consistent, healthy changes with diet and exercise, this creates a sort of domino effect.

In the book Us! Our Life. Our Health. Our Legacy,1 co-authored by Dr. Bradley and her colleague, Margaret L. McKenzie, MD, the authors highlight the 10 healthiest behaviors to bring about youthfulness and robust health:

- Walk at least 30-45 minutes per day most days of the week.

- Engage in resistance training 2-3 days per week.

- Eat a primarily plant-based diet made up of a variety of whole foods.

- Do not smoke.

- Maintain a waist line that measures less than half your height.

- Drink alcohol only in moderation.

- Get 7-8 hours of sleep most nights.

- Forgive.

- Have gratitude.

- Believe in something greater than yourself.

- Bradley LD, McKenzie ML. Us! Our life. Our health. Our legacy. Las Vegas, Nevada: The Literary Front Publishing Co., LLC; 2016.

Dr. Bradley: I think we need to get to the root cause of these clinical problems and provide the resources and support that patients need to reverse or even prevent these diseases. Clinicians need to become more aware—be an example and a role model. Our patients are watching us as much as we are watching them. Together, we can form good partnerships in order to promote better health.

Dr. Bradley: I think when you are about to be a change agent for your body and become what I call the best version of yourself, you can have these great ideas, but you need to turn those ideas into actions and make them consistent. And we know that is difficult to do, so I do try to have patients write down specific goals, their plan for achieving them, and list the reasons why it is important for them to reach their goals. That gives them something tangible to look at when the going gets tough. It is also important to work into the contract ways to reward positive behaviors when goals are met, and to plan for challenges and setbacks and how to get back on track.

I also encourage patients to document their progress and learn how to make quick adjustments when necessary to get back on track. Another important element involves setting milestones—by what date are you going to reach this goal? Like any other contract, I have my patients date and sign their wellness contracts. I also encourage them to visualize what their new self is going to look like, how they will feel when they reach their goal, what they will wear, and what activities they will engage in.

Related article:

Obesity medicine: How to incorporate it into your practice

Dr. Bradley: I do, but the amount of nutrition education that most of us get in medical school is minimal to nonexistent and not practical. As physicians, we know that food is health, exercise is fitness, and that our patients need both of them. We also know that we did not get this information in school and that our education was more about treating disease than preventing disease. Many of us were not trained in robot surgery either, because it did not exist. So what did we do? We took classes, attended lectures, read books, and learned. We can do the same with wellness. There are many courses around the country. We have to begin to relearn and reteach ourselves about health, nutrition, and exercise and then pass that information on to our patients—be a resource and a guide. We should be able to write a prescription for health as quickly as we can write a prescription for insulin or a statin.

I also bring up portion distortion with my patients. The National Institutes of Health has resources on their website (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational /wecan/eat-right/portion-distortion.html) that include great visuals that show portion sizes 20 years ago and what they are now. For instance, 20 years ago a bagel was 3 inches and 140 calories; today’s bagel is 6 inches and 350 calories (plus whatever toppings are added). I tell that to my patients and then explain how much more exercise is needed to burn off just that 1 bagel.

Related article:

How to help your patients control gestational weight gain

Dr. Bradley: They may not know that term directly, but I think people understand that you have the potential to pass on poor lifestyle and/or health issues related to how things are when you are in utero and later in life. It gets back to letting people know to be healthy in pregnancy and even pre-pregnancy, and that includes one’s emotional state, physical state, and spiritual state. We are what we are in our mother’s womb. Getting the best start in life starts with a healthy mom, healthy dad, and a healthy environment.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Over the past 3 decades, the prevalence of overweight and obesity has increased dramatically in the United States. A study published in 2016 showed the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity in 2013–2014 was 35% among men and 40.4% among women.1 It comes as no surprise that increased reliance on inexpensive fast foods coupled with progressively more sedentary lifestyles have been implicated as causative factors.2

With the rise in obesity also has come an attendant rise in related chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Women who are obese are also at risk for certain women’s health conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome, breast cancer, and endometrial cancer.

It is clear that curbing this public health crisis will require concerted efforts from individuals, clinicians, and policy makers, as well as changes in societal norms.

Linda D. Bradley, MD: I think it is important for us not to lecture our patients. I could list all of the things that patients should or could do to prevent or even reverse disease states, in terms of eating right and exercising, but I think motivational interviewing is a more productive approach to elicit and evoke change (see “Principles and practice of motivational interviewing”). I used to preach to my patients. I would say, “You know, if you stay at this weight, you’re going to get diabetes, you’re going to increase your breast cancer risk, you’re going to have abnormal bleeding, you’re not going to be able to get pregnant,” and so on. It is easy to slip into that in the 7 minutes that you have with your patient, but to me, that is not the right way.

With motivational interviewing, our interactions with patients are shaped by:

- asking

- advising

- assisting

- arranging.

We begin by asking permission: “Do you mind if we talk about your weight?” or “Can we talk about your level of exercise?” Once the patient has granted permission, we ask open-ended questions and use reflective listening: “What I hear you saying is that you are concerned you will not be able to lose the weight,” or “It sounds like you don’t like to exercise, but you are worried about the health consequences of that.”

Utilizing motivational interviewing to help patients identify thoughts and feelings that contribute to unhealthy behaviors--and replacing those thoughts and feelings with new thought patterns that aid in behavior change--has been shown to be an effective and efficient facilitator for change. By incorporating the following principles of motivational interviewing into practice, clinicians can have an important impact on the prevention or management of serious diseases in women1:

- Express empathy and avoid arguments. "I know it has been difficult for you to take the first step to losing weight. That is something that is difficult for a lot of my patients. How can I help you take that first step?"

- Develop discrepancies to help the patient understand the difference between her behavior and her goals. "You have said that you would like to lose some weight. I think you know that exercise would help with that. Why do you think it has been hard for you to start exercising more?"

- Roll with resistance and provide personalized feedback to help the patient find ways to succeed. "What I hear you saying is your work schedule does not allow you time to work out at the gym. What about walking during lunch breaks or taking the stairs instead of the elevator--is that something you think you can commit to doing?"

- Support self-efficacy and elicit self-motivation. "What would you like to see differently about your health? What makes you think you need to change? What happens if you don't change?"

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 423: Motivational interviewing: a tool for behavioral change. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):243-246.

I find these skills useful for addressing anything from smoking to drinking to weight management to excessive shopping—any extreme behavior that is affecting a patient negatively. When a patient is not ready to talk about her clinical problems or make changes, I let her know my door is always open to her and that I have many resources available to help her when she is ready (TABLE).4 In those cases, I might say something like, “I have many patients who really don’t want to talk about this when I first ask them, but I just want you to know, Mrs. Jones, that I want you to succeed and I want you to be healthy. We have a team approach to taking care of all of you, and when you are ready, we are here to help.”

Related article:

2017 Update on fertility: Effects of obesity on reproduction

It is important to provide practical advice to patients—including how much to exercise, the importance of keeping a food journal, and determining a goal for slow, safe weight loss—and provide resources as necessary (such as for Weight Watchers, nutrition, and dieticians). Each day we have more than 30 opportunities to select foods to eat, drink, or purchase. Have a plan and advise your patients do the same. Recommend patients cook their own meals. Suggest weight loss apps. Counsel them to celebrate successes, find a buddy (for social support), practice positive self-talk (positive language), and plan for challenges (travel, parties, working late) and setbacks, which do not need to become a fall. Find an activity or exercise that the patient enjoys and tell them to seek professional help if needed.

Read about how to educate your patients on wellness.

Dr. Bradley: About 86% of the health care dollars spent in the United States are due to chronic diseases, and chronic diseases are the leading cause of death and disability in the country.5 The most common chronic diseases—cardiovascular disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, colon cancer, depression, dementia, cognitive problems, higher rates of fractures—all have been associated, at least in part, with unhealthy food choices and lack of exercise. That applies to breast cancer, too.

The good news is, we can prevent and even reverse disease. As Hippocrates said, let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food. We have all seen success stories where consistent exercise and dietary changes definitely change the paradigm for what the disease state represents. A multiplicity of factors affect poor health—noncompliance, obesity, smoking—but when we begin to make consistent, healthy changes with diet and exercise, this creates a sort of domino effect.

In the book Us! Our Life. Our Health. Our Legacy,1 co-authored by Dr. Bradley and her colleague, Margaret L. McKenzie, MD, the authors highlight the 10 healthiest behaviors to bring about youthfulness and robust health:

- Walk at least 30-45 minutes per day most days of the week.

- Engage in resistance training 2-3 days per week.

- Eat a primarily plant-based diet made up of a variety of whole foods.

- Do not smoke.

- Maintain a waist line that measures less than half your height.

- Drink alcohol only in moderation.

- Get 7-8 hours of sleep most nights.

- Forgive.

- Have gratitude.

- Believe in something greater than yourself.

- Bradley LD, McKenzie ML. Us! Our life. Our health. Our legacy. Las Vegas, Nevada: The Literary Front Publishing Co., LLC; 2016.

Dr. Bradley: I think we need to get to the root cause of these clinical problems and provide the resources and support that patients need to reverse or even prevent these diseases. Clinicians need to become more aware—be an example and a role model. Our patients are watching us as much as we are watching them. Together, we can form good partnerships in order to promote better health.

Dr. Bradley: I think when you are about to be a change agent for your body and become what I call the best version of yourself, you can have these great ideas, but you need to turn those ideas into actions and make them consistent. And we know that is difficult to do, so I do try to have patients write down specific goals, their plan for achieving them, and list the reasons why it is important for them to reach their goals. That gives them something tangible to look at when the going gets tough. It is also important to work into the contract ways to reward positive behaviors when goals are met, and to plan for challenges and setbacks and how to get back on track.

I also encourage patients to document their progress and learn how to make quick adjustments when necessary to get back on track. Another important element involves setting milestones—by what date are you going to reach this goal? Like any other contract, I have my patients date and sign their wellness contracts. I also encourage them to visualize what their new self is going to look like, how they will feel when they reach their goal, what they will wear, and what activities they will engage in.

Related article:

Obesity medicine: How to incorporate it into your practice

Dr. Bradley: I do, but the amount of nutrition education that most of us get in medical school is minimal to nonexistent and not practical. As physicians, we know that food is health, exercise is fitness, and that our patients need both of them. We also know that we did not get this information in school and that our education was more about treating disease than preventing disease. Many of us were not trained in robot surgery either, because it did not exist. So what did we do? We took classes, attended lectures, read books, and learned. We can do the same with wellness. There are many courses around the country. We have to begin to relearn and reteach ourselves about health, nutrition, and exercise and then pass that information on to our patients—be a resource and a guide. We should be able to write a prescription for health as quickly as we can write a prescription for insulin or a statin.

I also bring up portion distortion with my patients. The National Institutes of Health has resources on their website (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational /wecan/eat-right/portion-distortion.html) that include great visuals that show portion sizes 20 years ago and what they are now. For instance, 20 years ago a bagel was 3 inches and 140 calories; today’s bagel is 6 inches and 350 calories (plus whatever toppings are added). I tell that to my patients and then explain how much more exercise is needed to burn off just that 1 bagel.

Related article:

How to help your patients control gestational weight gain

Dr. Bradley: They may not know that term directly, but I think people understand that you have the potential to pass on poor lifestyle and/or health issues related to how things are when you are in utero and later in life. It gets back to letting people know to be healthy in pregnancy and even pre-pregnancy, and that includes one’s emotional state, physical state, and spiritual state. We are what we are in our mother’s womb. Getting the best start in life starts with a healthy mom, healthy dad, and a healthy environment.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, et al. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA.2016;315(21):2284Arial–2291.

- Sturm R, An R. Obesity and economic environments. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(5):337Arial–350.

- Bradley LD, McKenzie ML. Us! Our life. Our health. Our legacy. Las Vegas, Nevada: The Literary Front Publishing Co., LLC; 2016.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 423: Motivational interviewing: a tool for behavioral change. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):243–246.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic disease overview. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm. Updated June 28, 2017. Accessed November 3, 2017.

- Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, et al. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA.2016;315(21):2284Arial–2291.

- Sturm R, An R. Obesity and economic environments. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(5):337Arial–350.

- Bradley LD, McKenzie ML. Us! Our life. Our health. Our legacy. Las Vegas, Nevada: The Literary Front Publishing Co., LLC; 2016.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 423: Motivational interviewing: a tool for behavioral change. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):243–246.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic disease overview. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm. Updated June 28, 2017. Accessed November 3, 2017.