User login

Identification of geographic clusters in which children have higher rates of underimmunization, or whose parents outright refuse vaccination, can help identify similar pockets of vaccine underutilization and help health care providers better focus their approach to providing immunization interventions around the country, according to the findings of a new study published in Pediatrics.

“For optimal public health and patient care, clinicians and health care systems ideally should tailor care to their communities,” wrote Dr. Tracy A. Lieu of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland, and her associates.

“The ability to identify clusters of underimmunization and vaccine refusal would help providers focus their efforts on the parents in communities with the greatest concerns, as well as identify areas at elevated risk for outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases” (Pediatrics 2015 [doi:10.1542/peds.2014-2715]).

In a retrospective cohort study, Dr. Lieu and her coinvestigators looked at children with continuous membership in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California, aged from birth to age 36 months, between Jan. 1, 2000, and December 31, 2009. A total of 154,424 children in 13 northern California counties were selected for inclusion in the study. Children were classified as underimmunized if they missed at least one vaccine by age 36 months, while vaccine refusal was classified using ICD-9-CM codes V6405, V6406, or V6407, as per the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification for subjects who refused even one vaccination at any time prior to age 36 months.

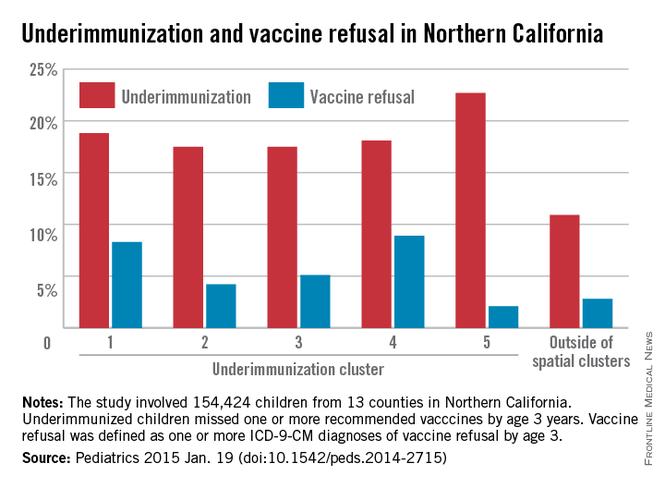

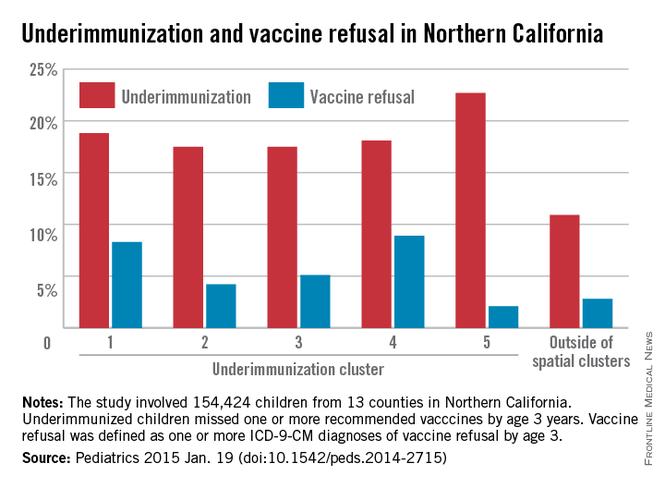

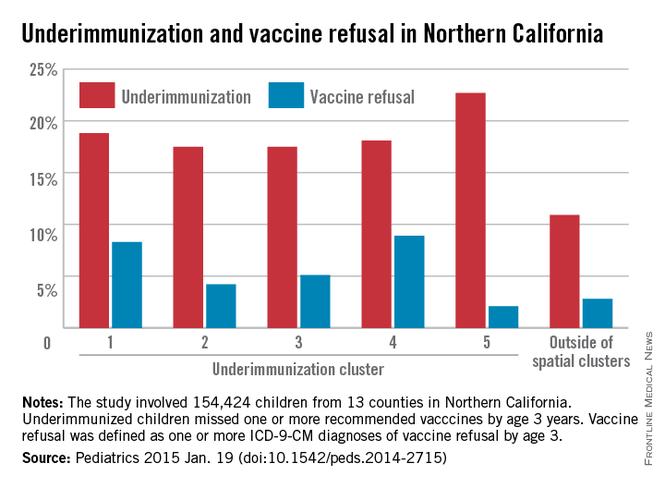

Spatial scan analysis of all the accumulated data revealed five statistically significant geographic clusters in which underimmunization was more pronounced, nearly all located in the greater Sacramento and San Francisco metropolitan areas, with underimmunization rates over the course of the study period ranging from 18.1% in northern San Francisco and southern Marin counties to 22.7% in Vallejo (P = .023 and P = .042, respectively).

Across all 13 counties surveyed, rates of underimmunization increased from 8.1% in 2001-2005 to 12.4% in 2010-2012; the peak rate in a single year was 13%, achieved in 2010, while the mean annual increase in underimmunization across all 13 counties was 5.9%. In terms of race/ethnicity, higher percentages of Asian and Hispanic subjects were fully immunized compared with those who were white, black, or of unknown race/ethnicity.

Children in the most statistically significant cluster – the East Bay area, from Richmond to San Leandro – had 1.58 (P < .001) times the rate of underimmunization as displayed by other clusters, with 650 actual underimmunized cases during 2010-2012. Vaccine refusal was also clustered, with rates of 5.5% to 13.5% within clusters, compared with 2.6% outside of them.

Underimmunization of measles, mumps, and rubella and varicella vaccines also clustered in similar geographic areas, a cause for great concern given the recent outbreaks of measles at the Disneyland theme park in Anaheim, Calif. A study published last year, highlights the greater need for health care providers to educate parents about the importance of MMR vaccinations, saying that by doing so, they greatly increase the likelihood of parents agreeing to have their children properly vaccinated (Pediatrics 2014;134:e675-e83). Outbreaks of pertussis also have proved troublesome in recent years, exacerbating the need for greater intervention regarding vaccinating children early and when necessary.

“The existence of clusters may put clinical groups in these locations at a disadvantage in achieving immunization quality benchmarks,” noted Dr. Lieu and her coauthors, adding that “nonmedical exemptions from immunization in California clustered geographically and were associated with clusters of pertussis cases [and] many previous studies have found that vaccine refusal and delay are associated with elevated risk of measles and pertussis outbreaks, as well as elevated individual risks of measles, pertussis, varicella, and pneumococcal infections.”

Funding was provided by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Pilot Project contract. Coauthor Dr Klein receives research support from Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi Pasteur, and Nuron Biotech; no other authors reported any relevant financial disclosures.

This study essentially confirms what we’ve known anecdotally and have had some evidence of before: Underimmunization that results from refusal by concerned parents who do not want their children receiving all the recommended vaccines is not randomly distributed in the population.

These geographic clusters occur not only in California, but in Oregon, Washington, and many other states, but there are predictors for this behavior at the individual and group levels. For example, white, upper-class, higher socioeconomic groups tend to see higher rates; interestingly enough, this paper finds higher underimmunization in areas with more individuals of graduate level or higher education, and also in areas with more poverty. Parents tend to have more and more questions about the safety, efficacy, and need for these vaccinations, and this will often lead to delay or flat-out refusal.

I don’t think any of this is completely new or surprising. The investigators used a new statistical approach for detecting these clusters within the Kaiser database, but there are no real surprises here, and there is certainly no reason to doubt these findings; this is a real phenomenon.

There needs to be more follow-up research in order to bring underimmunization to a minimum; we need to understand more fully what drives this behavior and how we can address and allay people’s concerns, but I wouldn’t be able to speak on that since it’s in the realm of psychology or sociology.

Dr. Arthur L. Reingold is a professor and the head of epidemiology at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health.

This study essentially confirms what we’ve known anecdotally and have had some evidence of before: Underimmunization that results from refusal by concerned parents who do not want their children receiving all the recommended vaccines is not randomly distributed in the population.

These geographic clusters occur not only in California, but in Oregon, Washington, and many other states, but there are predictors for this behavior at the individual and group levels. For example, white, upper-class, higher socioeconomic groups tend to see higher rates; interestingly enough, this paper finds higher underimmunization in areas with more individuals of graduate level or higher education, and also in areas with more poverty. Parents tend to have more and more questions about the safety, efficacy, and need for these vaccinations, and this will often lead to delay or flat-out refusal.

I don’t think any of this is completely new or surprising. The investigators used a new statistical approach for detecting these clusters within the Kaiser database, but there are no real surprises here, and there is certainly no reason to doubt these findings; this is a real phenomenon.

There needs to be more follow-up research in order to bring underimmunization to a minimum; we need to understand more fully what drives this behavior and how we can address and allay people’s concerns, but I wouldn’t be able to speak on that since it’s in the realm of psychology or sociology.

Dr. Arthur L. Reingold is a professor and the head of epidemiology at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health.

This study essentially confirms what we’ve known anecdotally and have had some evidence of before: Underimmunization that results from refusal by concerned parents who do not want their children receiving all the recommended vaccines is not randomly distributed in the population.

These geographic clusters occur not only in California, but in Oregon, Washington, and many other states, but there are predictors for this behavior at the individual and group levels. For example, white, upper-class, higher socioeconomic groups tend to see higher rates; interestingly enough, this paper finds higher underimmunization in areas with more individuals of graduate level or higher education, and also in areas with more poverty. Parents tend to have more and more questions about the safety, efficacy, and need for these vaccinations, and this will often lead to delay or flat-out refusal.

I don’t think any of this is completely new or surprising. The investigators used a new statistical approach for detecting these clusters within the Kaiser database, but there are no real surprises here, and there is certainly no reason to doubt these findings; this is a real phenomenon.

There needs to be more follow-up research in order to bring underimmunization to a minimum; we need to understand more fully what drives this behavior and how we can address and allay people’s concerns, but I wouldn’t be able to speak on that since it’s in the realm of psychology or sociology.

Dr. Arthur L. Reingold is a professor and the head of epidemiology at the University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health.

Identification of geographic clusters in which children have higher rates of underimmunization, or whose parents outright refuse vaccination, can help identify similar pockets of vaccine underutilization and help health care providers better focus their approach to providing immunization interventions around the country, according to the findings of a new study published in Pediatrics.

“For optimal public health and patient care, clinicians and health care systems ideally should tailor care to their communities,” wrote Dr. Tracy A. Lieu of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland, and her associates.

“The ability to identify clusters of underimmunization and vaccine refusal would help providers focus their efforts on the parents in communities with the greatest concerns, as well as identify areas at elevated risk for outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases” (Pediatrics 2015 [doi:10.1542/peds.2014-2715]).

In a retrospective cohort study, Dr. Lieu and her coinvestigators looked at children with continuous membership in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California, aged from birth to age 36 months, between Jan. 1, 2000, and December 31, 2009. A total of 154,424 children in 13 northern California counties were selected for inclusion in the study. Children were classified as underimmunized if they missed at least one vaccine by age 36 months, while vaccine refusal was classified using ICD-9-CM codes V6405, V6406, or V6407, as per the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification for subjects who refused even one vaccination at any time prior to age 36 months.

Spatial scan analysis of all the accumulated data revealed five statistically significant geographic clusters in which underimmunization was more pronounced, nearly all located in the greater Sacramento and San Francisco metropolitan areas, with underimmunization rates over the course of the study period ranging from 18.1% in northern San Francisco and southern Marin counties to 22.7% in Vallejo (P = .023 and P = .042, respectively).

Across all 13 counties surveyed, rates of underimmunization increased from 8.1% in 2001-2005 to 12.4% in 2010-2012; the peak rate in a single year was 13%, achieved in 2010, while the mean annual increase in underimmunization across all 13 counties was 5.9%. In terms of race/ethnicity, higher percentages of Asian and Hispanic subjects were fully immunized compared with those who were white, black, or of unknown race/ethnicity.

Children in the most statistically significant cluster – the East Bay area, from Richmond to San Leandro – had 1.58 (P < .001) times the rate of underimmunization as displayed by other clusters, with 650 actual underimmunized cases during 2010-2012. Vaccine refusal was also clustered, with rates of 5.5% to 13.5% within clusters, compared with 2.6% outside of them.

Underimmunization of measles, mumps, and rubella and varicella vaccines also clustered in similar geographic areas, a cause for great concern given the recent outbreaks of measles at the Disneyland theme park in Anaheim, Calif. A study published last year, highlights the greater need for health care providers to educate parents about the importance of MMR vaccinations, saying that by doing so, they greatly increase the likelihood of parents agreeing to have their children properly vaccinated (Pediatrics 2014;134:e675-e83). Outbreaks of pertussis also have proved troublesome in recent years, exacerbating the need for greater intervention regarding vaccinating children early and when necessary.

“The existence of clusters may put clinical groups in these locations at a disadvantage in achieving immunization quality benchmarks,” noted Dr. Lieu and her coauthors, adding that “nonmedical exemptions from immunization in California clustered geographically and were associated with clusters of pertussis cases [and] many previous studies have found that vaccine refusal and delay are associated with elevated risk of measles and pertussis outbreaks, as well as elevated individual risks of measles, pertussis, varicella, and pneumococcal infections.”

Funding was provided by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Pilot Project contract. Coauthor Dr Klein receives research support from Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi Pasteur, and Nuron Biotech; no other authors reported any relevant financial disclosures.

Identification of geographic clusters in which children have higher rates of underimmunization, or whose parents outright refuse vaccination, can help identify similar pockets of vaccine underutilization and help health care providers better focus their approach to providing immunization interventions around the country, according to the findings of a new study published in Pediatrics.

“For optimal public health and patient care, clinicians and health care systems ideally should tailor care to their communities,” wrote Dr. Tracy A. Lieu of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland, and her associates.

“The ability to identify clusters of underimmunization and vaccine refusal would help providers focus their efforts on the parents in communities with the greatest concerns, as well as identify areas at elevated risk for outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases” (Pediatrics 2015 [doi:10.1542/peds.2014-2715]).

In a retrospective cohort study, Dr. Lieu and her coinvestigators looked at children with continuous membership in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California, aged from birth to age 36 months, between Jan. 1, 2000, and December 31, 2009. A total of 154,424 children in 13 northern California counties were selected for inclusion in the study. Children were classified as underimmunized if they missed at least one vaccine by age 36 months, while vaccine refusal was classified using ICD-9-CM codes V6405, V6406, or V6407, as per the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification for subjects who refused even one vaccination at any time prior to age 36 months.

Spatial scan analysis of all the accumulated data revealed five statistically significant geographic clusters in which underimmunization was more pronounced, nearly all located in the greater Sacramento and San Francisco metropolitan areas, with underimmunization rates over the course of the study period ranging from 18.1% in northern San Francisco and southern Marin counties to 22.7% in Vallejo (P = .023 and P = .042, respectively).

Across all 13 counties surveyed, rates of underimmunization increased from 8.1% in 2001-2005 to 12.4% in 2010-2012; the peak rate in a single year was 13%, achieved in 2010, while the mean annual increase in underimmunization across all 13 counties was 5.9%. In terms of race/ethnicity, higher percentages of Asian and Hispanic subjects were fully immunized compared with those who were white, black, or of unknown race/ethnicity.

Children in the most statistically significant cluster – the East Bay area, from Richmond to San Leandro – had 1.58 (P < .001) times the rate of underimmunization as displayed by other clusters, with 650 actual underimmunized cases during 2010-2012. Vaccine refusal was also clustered, with rates of 5.5% to 13.5% within clusters, compared with 2.6% outside of them.

Underimmunization of measles, mumps, and rubella and varicella vaccines also clustered in similar geographic areas, a cause for great concern given the recent outbreaks of measles at the Disneyland theme park in Anaheim, Calif. A study published last year, highlights the greater need for health care providers to educate parents about the importance of MMR vaccinations, saying that by doing so, they greatly increase the likelihood of parents agreeing to have their children properly vaccinated (Pediatrics 2014;134:e675-e83). Outbreaks of pertussis also have proved troublesome in recent years, exacerbating the need for greater intervention regarding vaccinating children early and when necessary.

“The existence of clusters may put clinical groups in these locations at a disadvantage in achieving immunization quality benchmarks,” noted Dr. Lieu and her coauthors, adding that “nonmedical exemptions from immunization in California clustered geographically and were associated with clusters of pertussis cases [and] many previous studies have found that vaccine refusal and delay are associated with elevated risk of measles and pertussis outbreaks, as well as elevated individual risks of measles, pertussis, varicella, and pneumococcal infections.”

Funding was provided by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Pilot Project contract. Coauthor Dr Klein receives research support from Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi Pasteur, and Nuron Biotech; no other authors reported any relevant financial disclosures.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Underimmunization occurs in geographic clusters, which can be used to predict areas in which underutilization of vaccines occurs and where focused intervention may be necessary.

Major finding: Out of five statistically significant clusters of underimmunization that were identified, underimmunization rates within clusters ranged from 18% to 23%, while the rate outside clusters was 11%.

Data source: Retrospective cohort study of 154,424 children in 13 counties, all of whom have membership in Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

Disclosures: Funding was provided by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Pilot Project contract. Coauthor Dr Klein receives research support from Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, MedImmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi Pasteur, and Nuron Biotech; no other authors reported any relevant financial disclosures.