User login

Incidental findings create both medical and logistical challenges regarding communication.1,2 Pulmonary nodules are among the most frequent and medically relevant incidental findings, being noted in up to 8.4% of abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans.3 There are guidelines regarding proper follow-up and management of such incidental pulmonary nodules, but appropriate evidence-based surveillance imaging is often not performed, and many patients remain uninformed. Collins et al.4 reported that, before initiation of a standardized protocol, only 17.7% of incidental findings were communicated to patients admitted to the trauma service; after protocol initiation, the rate increased to 32.4%. The hospital discharge summary provides an opportunity to communicate incidental findings to patients and their medical care providers, but Kripalani et al.5 raised questions regarding the current completeness and accuracy of discharge summaries, reporting that 65% of discharge summaries omitted relevant diagnostic testing, and 30% omitted a follow-up plan.

We conducted a study to determine how often incidental pulmonary nodules found on abdominal CT are documented in the discharge summary, and to identify factors associated with pulmonary nodule inclusion.

METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study of hospitalized patients ≥35 years of age who underwent in-patient abdominal CT between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2014. Patients were identified by cross-referencing hospital admissions with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes indicating abdominal CT (74176, 74177, 74178, 74160, 74150, 74170). Patients with chest CT (CPT codes 71260, 71250, 71270) during that hospitalization or within 30 days before admission were excluded to ensure that pulmonary nodules were incidental and asymptomatic. The index hospitalization was defined as the first hospitalization during which the patient was diagnosed with an incidental pulmonary nodule on abdominal CT, or the first hospitalization during the study period for patients without pulmonary nodules. All patient charts were manually reviewed, and baseline age, sex, and smoking status data collected.

Radiology reports were electronically screened for the words nodule and nodules and then confirmed through manual review of the full text reports. Nodules described as tiny (without other size description) were assumed to be <4 mm in size, per manual review of a small sample. Nodules were deemed as falling outside the Fleischner Society criteria guidelines (designed for indeterminate pulmonary nodules), and were therefore excluded, if any of seven criteria were met: The nodule was (1) cavitary, (2) associated with a known metastatic disease, (3) associated with a known granulomatous disease, (4) associated with a known inflammatory process, (5) reported likely to represent atelectasis, (6) reported likely to be a lymph node, or (7) previously biopsied.4

For each patient with pulmonary nodules, a personal history of cancer was obtained. Nodule size, characteristics, and stability compared with available prior imaging were recorded. Radiology reports were reviewed to determine if pulmonary nodules were mentioned in the summary headings of the reports or in the body of the reports and whether specific follow-up recommendations were provided. Hospital discharge summaries were reviewed for documentation of pulmonary nodule(s) and follow-up recommendations. Discharging service (medical/medical subspecialty, surgical/surgical subspecialty) was noted, along with the patients’ condition at discharge (alive, alive on hospice, deceased).

The frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules on abdominal CT during hospitalization and the frequency of nodules requiring follow-up were reported using a point estimate and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The χ2 test was used to compare the frequency of pulmonary nodules across patient groups. In addition, for patients found to have incidental nodules requiring follow-up, the χ2 test was used to compare across groups the percentage of patients with discharge documentation of the incidental nodule. In all cases, 2-tailed Ps are reported, with P ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

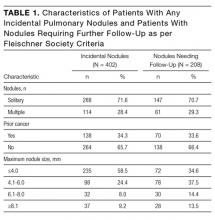

Between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2014, 7173 patients ≥35 years old underwent in-patient abdominal CT without concurrent chest CT. Of these patients, 62.2% were ≥60 years old, 50.6% were men, and 45.5% were current or former smokers. Incidental pulmonary nodules were noted in 402 patients (5.6%; 95% CI, 5.1%-6.2%), of whom 68.7% were ≥60 years old, 56.5% were men, and 46.3% were current or former smokers. Increasing age (P = 0.004) and male sex (P = 0.015) were associated with increased frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules, but smoking status (P = 0.586) was not. Of patients with incidental nodules, 71.6% had solitary nodules, and 58.5% had a maximum nodule size of ≤4 mm (Table 1). Based on smoking status, nodule size, and reported size stability, 208 patients (2.9%; 95% CI, 2.5%-3.3%) required follow-up surveillance as per 2005 Fleischner Society guidelines. Among solitary pulmonary nodules requiring further surveillance (n = 147), the mean risk of malignancy based on the Mayo Clinic solitary pulmonary nodule risk calculator was 7.9% (interquartile range, 3.0%-10.5%), with 28% having a malignancy risk of ≥10%.6

Of the 208 patients with nodules requiring further surveillance, only 48 (23%) received discharge summaries documenting the nodule; 34 of these summaries included a recommendation for nodule follow-up, with 19 of the recommendations including a time frame for repeat CT. Three factors were positively associated with documentation of the pulmonary nodule in the discharge summary: mention of the pulmonary nodule in the summary headings of the radiology report (P < 0.001), radiologist recommendation for further surveillance (P < 0.001), and medical discharging service (P = 0.016) (Table 2). The highest rate of pulmonary nodule inclusion in the discharge summary (42%) was noted among patients for whom the radiology report included specific recommendations.

DISCUSSION

The frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules reported on abdominal CT in our study (5.6%) is consistent with frequencies reported in similar studies. Wu et al.7 (reviewing 141,406 abdominal CT scans) and Alpert et al.8 (reviewing 12,287 abdominal CT scans) reported frequencies of 2.5% and 3%, respectively, while Rinaldi et al.3 (reviewing 243 abdominal CT scans) reported a higher frequency, 8.4%. Variation likely results from patient factors and the individual radiologist’s attention to incidental pulmonary findings. Rinaldi et al. suggested that up to 39% of abdominal CT scans include pulmonary nodules on independent review, raising the possibility of significant underreporting. In our study, we focused on pulmonary nodules included in the radiology report to tailor the relevance of our study to the hospital medicine community. We also included only those incidental nodules falling within the purview of the Fleischner Society criteria in order to analyze only findings with established follow-up guidelines.

The rate of pulmonary nodule documentation in our study was low overall (23%) but consistent with the literature. Collins et al.,4 for example, reported that only 17.7% of patients with trauma were notified of incidental CT findings by either the discharge summary or an appropriate specialist consultation. Various contributing factors can be hypothesized. First, incidental pulmonary nodules are discovered largely in the context of evaluation for other symptomatic conditions, which can overshadow their importance. Second, the lack of clear patient-friendly education materials regarding incidental pulmonary nodules can complicate discussions with patients. Third, many electronic health record (EHR) systems cannot automatically pull incidental findings into the discharge summary and instead rely on provider vigilance.

As our study does, the literature highlights the importance of the radiology report in communicating incidental findings. In a review of >1000 pulmonary angiographic CT studies, Blagev et al.9 reported an overall follow-up rate of 29% (28/96) among patients with incidental pulmonary nodules, but none of the 12 patients with pulmonary nodules mentioned in the body of the report (rather than in the summary headings) received adequate follow-up. Similarly, in Shuaib et al.,10 radiology reports that included follow-up recommendations were more likely to change patient treatment than reports without follow-up recommendations (70% vs 2%). However, our data also show that radiologist recommendations alone are insufficient to ensure adequate communication of incidental findings.

The literature regarding the most cost-effective means of addressing this quality gap is limited. Some institutions have integrated their EHR systems to allow radiologists to flag incidental findings for auto-population in a dedicated section of the discharge summary. Although these efforts can be helpful, documentation alone does not save lives without appropriate follow-up and intervention. Some institutions have hired dedicated nursing staff as incidental finding coordinators. For high-risk incidental findings, Sperry et al.11 reported that hiring an incidental findings coordinator helped their level I trauma center achieve nearly complete documentation, patient notification, and confirmation of posthospital follow-up appointments. Such solutions, however, are labor-intensive and still rely on appropriate primary care follow-up.

Strengths of our study include its relatively large size and particular focus on the issues and decisions facing hospital medicine providers. By focusing on incidental pulmonary nodules reported on abdominal CT, and excluding patients with concurrent chest CT, we avoided including patients with symptomatic or previously identified pulmonary findings. Study limitations include the cross-sectional, retrospective design, which did not include follow-up data regarding such outcomes as rates of appropriate follow-up surveillance and subsequent lung cancer diagnoses. Our single-center study findings may not apply to all hospital practice settings, though they are consistent with the literature with comparison data.

Our study results highlight the need for a multidisciplinary systems-based approach to incidental pulmonary nodule documentation, communication, and follow-up surveillance.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Armao D, Smith JK. Overuse of computed tomography and the onslaught of incidental findings. N C Med J. 2014;75(2):127. PubMed

2. Gould MK, Tang T, Liu IL, et al. Recent trends in the identification of incidental pulmonary nodules. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(10):1208-1214. PubMed

3. Rinaldi MF, Bartalena T, Giannelli G, et al. Incidental lung nodules on CT examinations of the abdomen: prevalence and reporting rates in the PACS era. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74(3):e84-e88. PubMed

4. Collins CE, Cherng N, McDade T, et al. Improving patient notification of solid abdominal viscera incidental findings with a standardized protocol. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2015;9(1):1. PubMed

5. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. PubMed

6. Swensen SJ, Silverstein MD, Ilstrup DM, Schleck CD, Edell ES. The probability of malignancy in solitary pulmonary nodules. Application to small radiologically indeterminate nodules. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(8):849-855. PubMed

7. Wu CC, Cronin CG, Chu JT, et al. Incidental pulmonary nodules detected on abdominal computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2012;36(6):641-645. PubMed

8. Alpert JB, Fantauzzi JP, Melamud K, Greenwood H, Naidich DP, Ko JP. Clinical significance of lung nodules reported on abdominal CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(4):793-799. PubMed

9. Blagev DP, Lloyd JF, Conner K, et al. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules and the radiology report. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11(4):378-383. PubMed

10. Shuaib W, Johnson JO, Salastekar N, Maddu KK, Khosa F. Incidental findings detected on abdomino-pelvic multidetector computed tomography performed in the acute setting [published correction appears in Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(7):811. Waqas, Shuaib (corrected to Shuaib, Waqas)]. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(1):36-39. PubMed

11. Sperry JL, Massaro MS, Collage RD, et al. Incidental radiographic findings after injury: dedicated attention results in improved capture, documentation, and management. Surgery. 2010;148(4):618-624. PubMed

Incidental findings create both medical and logistical challenges regarding communication.1,2 Pulmonary nodules are among the most frequent and medically relevant incidental findings, being noted in up to 8.4% of abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans.3 There are guidelines regarding proper follow-up and management of such incidental pulmonary nodules, but appropriate evidence-based surveillance imaging is often not performed, and many patients remain uninformed. Collins et al.4 reported that, before initiation of a standardized protocol, only 17.7% of incidental findings were communicated to patients admitted to the trauma service; after protocol initiation, the rate increased to 32.4%. The hospital discharge summary provides an opportunity to communicate incidental findings to patients and their medical care providers, but Kripalani et al.5 raised questions regarding the current completeness and accuracy of discharge summaries, reporting that 65% of discharge summaries omitted relevant diagnostic testing, and 30% omitted a follow-up plan.

We conducted a study to determine how often incidental pulmonary nodules found on abdominal CT are documented in the discharge summary, and to identify factors associated with pulmonary nodule inclusion.

METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study of hospitalized patients ≥35 years of age who underwent in-patient abdominal CT between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2014. Patients were identified by cross-referencing hospital admissions with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes indicating abdominal CT (74176, 74177, 74178, 74160, 74150, 74170). Patients with chest CT (CPT codes 71260, 71250, 71270) during that hospitalization or within 30 days before admission were excluded to ensure that pulmonary nodules were incidental and asymptomatic. The index hospitalization was defined as the first hospitalization during which the patient was diagnosed with an incidental pulmonary nodule on abdominal CT, or the first hospitalization during the study period for patients without pulmonary nodules. All patient charts were manually reviewed, and baseline age, sex, and smoking status data collected.

Radiology reports were electronically screened for the words nodule and nodules and then confirmed through manual review of the full text reports. Nodules described as tiny (without other size description) were assumed to be <4 mm in size, per manual review of a small sample. Nodules were deemed as falling outside the Fleischner Society criteria guidelines (designed for indeterminate pulmonary nodules), and were therefore excluded, if any of seven criteria were met: The nodule was (1) cavitary, (2) associated with a known metastatic disease, (3) associated with a known granulomatous disease, (4) associated with a known inflammatory process, (5) reported likely to represent atelectasis, (6) reported likely to be a lymph node, or (7) previously biopsied.4

For each patient with pulmonary nodules, a personal history of cancer was obtained. Nodule size, characteristics, and stability compared with available prior imaging were recorded. Radiology reports were reviewed to determine if pulmonary nodules were mentioned in the summary headings of the reports or in the body of the reports and whether specific follow-up recommendations were provided. Hospital discharge summaries were reviewed for documentation of pulmonary nodule(s) and follow-up recommendations. Discharging service (medical/medical subspecialty, surgical/surgical subspecialty) was noted, along with the patients’ condition at discharge (alive, alive on hospice, deceased).

The frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules on abdominal CT during hospitalization and the frequency of nodules requiring follow-up were reported using a point estimate and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The χ2 test was used to compare the frequency of pulmonary nodules across patient groups. In addition, for patients found to have incidental nodules requiring follow-up, the χ2 test was used to compare across groups the percentage of patients with discharge documentation of the incidental nodule. In all cases, 2-tailed Ps are reported, with P ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2014, 7173 patients ≥35 years old underwent in-patient abdominal CT without concurrent chest CT. Of these patients, 62.2% were ≥60 years old, 50.6% were men, and 45.5% were current or former smokers. Incidental pulmonary nodules were noted in 402 patients (5.6%; 95% CI, 5.1%-6.2%), of whom 68.7% were ≥60 years old, 56.5% were men, and 46.3% were current or former smokers. Increasing age (P = 0.004) and male sex (P = 0.015) were associated with increased frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules, but smoking status (P = 0.586) was not. Of patients with incidental nodules, 71.6% had solitary nodules, and 58.5% had a maximum nodule size of ≤4 mm (Table 1). Based on smoking status, nodule size, and reported size stability, 208 patients (2.9%; 95% CI, 2.5%-3.3%) required follow-up surveillance as per 2005 Fleischner Society guidelines. Among solitary pulmonary nodules requiring further surveillance (n = 147), the mean risk of malignancy based on the Mayo Clinic solitary pulmonary nodule risk calculator was 7.9% (interquartile range, 3.0%-10.5%), with 28% having a malignancy risk of ≥10%.6

Of the 208 patients with nodules requiring further surveillance, only 48 (23%) received discharge summaries documenting the nodule; 34 of these summaries included a recommendation for nodule follow-up, with 19 of the recommendations including a time frame for repeat CT. Three factors were positively associated with documentation of the pulmonary nodule in the discharge summary: mention of the pulmonary nodule in the summary headings of the radiology report (P < 0.001), radiologist recommendation for further surveillance (P < 0.001), and medical discharging service (P = 0.016) (Table 2). The highest rate of pulmonary nodule inclusion in the discharge summary (42%) was noted among patients for whom the radiology report included specific recommendations.

DISCUSSION

The frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules reported on abdominal CT in our study (5.6%) is consistent with frequencies reported in similar studies. Wu et al.7 (reviewing 141,406 abdominal CT scans) and Alpert et al.8 (reviewing 12,287 abdominal CT scans) reported frequencies of 2.5% and 3%, respectively, while Rinaldi et al.3 (reviewing 243 abdominal CT scans) reported a higher frequency, 8.4%. Variation likely results from patient factors and the individual radiologist’s attention to incidental pulmonary findings. Rinaldi et al. suggested that up to 39% of abdominal CT scans include pulmonary nodules on independent review, raising the possibility of significant underreporting. In our study, we focused on pulmonary nodules included in the radiology report to tailor the relevance of our study to the hospital medicine community. We also included only those incidental nodules falling within the purview of the Fleischner Society criteria in order to analyze only findings with established follow-up guidelines.

The rate of pulmonary nodule documentation in our study was low overall (23%) but consistent with the literature. Collins et al.,4 for example, reported that only 17.7% of patients with trauma were notified of incidental CT findings by either the discharge summary or an appropriate specialist consultation. Various contributing factors can be hypothesized. First, incidental pulmonary nodules are discovered largely in the context of evaluation for other symptomatic conditions, which can overshadow their importance. Second, the lack of clear patient-friendly education materials regarding incidental pulmonary nodules can complicate discussions with patients. Third, many electronic health record (EHR) systems cannot automatically pull incidental findings into the discharge summary and instead rely on provider vigilance.

As our study does, the literature highlights the importance of the radiology report in communicating incidental findings. In a review of >1000 pulmonary angiographic CT studies, Blagev et al.9 reported an overall follow-up rate of 29% (28/96) among patients with incidental pulmonary nodules, but none of the 12 patients with pulmonary nodules mentioned in the body of the report (rather than in the summary headings) received adequate follow-up. Similarly, in Shuaib et al.,10 radiology reports that included follow-up recommendations were more likely to change patient treatment than reports without follow-up recommendations (70% vs 2%). However, our data also show that radiologist recommendations alone are insufficient to ensure adequate communication of incidental findings.

The literature regarding the most cost-effective means of addressing this quality gap is limited. Some institutions have integrated their EHR systems to allow radiologists to flag incidental findings for auto-population in a dedicated section of the discharge summary. Although these efforts can be helpful, documentation alone does not save lives without appropriate follow-up and intervention. Some institutions have hired dedicated nursing staff as incidental finding coordinators. For high-risk incidental findings, Sperry et al.11 reported that hiring an incidental findings coordinator helped their level I trauma center achieve nearly complete documentation, patient notification, and confirmation of posthospital follow-up appointments. Such solutions, however, are labor-intensive and still rely on appropriate primary care follow-up.

Strengths of our study include its relatively large size and particular focus on the issues and decisions facing hospital medicine providers. By focusing on incidental pulmonary nodules reported on abdominal CT, and excluding patients with concurrent chest CT, we avoided including patients with symptomatic or previously identified pulmonary findings. Study limitations include the cross-sectional, retrospective design, which did not include follow-up data regarding such outcomes as rates of appropriate follow-up surveillance and subsequent lung cancer diagnoses. Our single-center study findings may not apply to all hospital practice settings, though they are consistent with the literature with comparison data.

Our study results highlight the need for a multidisciplinary systems-based approach to incidental pulmonary nodule documentation, communication, and follow-up surveillance.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Incidental findings create both medical and logistical challenges regarding communication.1,2 Pulmonary nodules are among the most frequent and medically relevant incidental findings, being noted in up to 8.4% of abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans.3 There are guidelines regarding proper follow-up and management of such incidental pulmonary nodules, but appropriate evidence-based surveillance imaging is often not performed, and many patients remain uninformed. Collins et al.4 reported that, before initiation of a standardized protocol, only 17.7% of incidental findings were communicated to patients admitted to the trauma service; after protocol initiation, the rate increased to 32.4%. The hospital discharge summary provides an opportunity to communicate incidental findings to patients and their medical care providers, but Kripalani et al.5 raised questions regarding the current completeness and accuracy of discharge summaries, reporting that 65% of discharge summaries omitted relevant diagnostic testing, and 30% omitted a follow-up plan.

We conducted a study to determine how often incidental pulmonary nodules found on abdominal CT are documented in the discharge summary, and to identify factors associated with pulmonary nodule inclusion.

METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study of hospitalized patients ≥35 years of age who underwent in-patient abdominal CT between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2014. Patients were identified by cross-referencing hospital admissions with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes indicating abdominal CT (74176, 74177, 74178, 74160, 74150, 74170). Patients with chest CT (CPT codes 71260, 71250, 71270) during that hospitalization or within 30 days before admission were excluded to ensure that pulmonary nodules were incidental and asymptomatic. The index hospitalization was defined as the first hospitalization during which the patient was diagnosed with an incidental pulmonary nodule on abdominal CT, or the first hospitalization during the study period for patients without pulmonary nodules. All patient charts were manually reviewed, and baseline age, sex, and smoking status data collected.

Radiology reports were electronically screened for the words nodule and nodules and then confirmed through manual review of the full text reports. Nodules described as tiny (without other size description) were assumed to be <4 mm in size, per manual review of a small sample. Nodules were deemed as falling outside the Fleischner Society criteria guidelines (designed for indeterminate pulmonary nodules), and were therefore excluded, if any of seven criteria were met: The nodule was (1) cavitary, (2) associated with a known metastatic disease, (3) associated with a known granulomatous disease, (4) associated with a known inflammatory process, (5) reported likely to represent atelectasis, (6) reported likely to be a lymph node, or (7) previously biopsied.4

For each patient with pulmonary nodules, a personal history of cancer was obtained. Nodule size, characteristics, and stability compared with available prior imaging were recorded. Radiology reports were reviewed to determine if pulmonary nodules were mentioned in the summary headings of the reports or in the body of the reports and whether specific follow-up recommendations were provided. Hospital discharge summaries were reviewed for documentation of pulmonary nodule(s) and follow-up recommendations. Discharging service (medical/medical subspecialty, surgical/surgical subspecialty) was noted, along with the patients’ condition at discharge (alive, alive on hospice, deceased).

The frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules on abdominal CT during hospitalization and the frequency of nodules requiring follow-up were reported using a point estimate and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). The χ2 test was used to compare the frequency of pulmonary nodules across patient groups. In addition, for patients found to have incidental nodules requiring follow-up, the χ2 test was used to compare across groups the percentage of patients with discharge documentation of the incidental nodule. In all cases, 2-tailed Ps are reported, with P ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2014, 7173 patients ≥35 years old underwent in-patient abdominal CT without concurrent chest CT. Of these patients, 62.2% were ≥60 years old, 50.6% were men, and 45.5% were current or former smokers. Incidental pulmonary nodules were noted in 402 patients (5.6%; 95% CI, 5.1%-6.2%), of whom 68.7% were ≥60 years old, 56.5% were men, and 46.3% were current or former smokers. Increasing age (P = 0.004) and male sex (P = 0.015) were associated with increased frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules, but smoking status (P = 0.586) was not. Of patients with incidental nodules, 71.6% had solitary nodules, and 58.5% had a maximum nodule size of ≤4 mm (Table 1). Based on smoking status, nodule size, and reported size stability, 208 patients (2.9%; 95% CI, 2.5%-3.3%) required follow-up surveillance as per 2005 Fleischner Society guidelines. Among solitary pulmonary nodules requiring further surveillance (n = 147), the mean risk of malignancy based on the Mayo Clinic solitary pulmonary nodule risk calculator was 7.9% (interquartile range, 3.0%-10.5%), with 28% having a malignancy risk of ≥10%.6

Of the 208 patients with nodules requiring further surveillance, only 48 (23%) received discharge summaries documenting the nodule; 34 of these summaries included a recommendation for nodule follow-up, with 19 of the recommendations including a time frame for repeat CT. Three factors were positively associated with documentation of the pulmonary nodule in the discharge summary: mention of the pulmonary nodule in the summary headings of the radiology report (P < 0.001), radiologist recommendation for further surveillance (P < 0.001), and medical discharging service (P = 0.016) (Table 2). The highest rate of pulmonary nodule inclusion in the discharge summary (42%) was noted among patients for whom the radiology report included specific recommendations.

DISCUSSION

The frequency of incidental pulmonary nodules reported on abdominal CT in our study (5.6%) is consistent with frequencies reported in similar studies. Wu et al.7 (reviewing 141,406 abdominal CT scans) and Alpert et al.8 (reviewing 12,287 abdominal CT scans) reported frequencies of 2.5% and 3%, respectively, while Rinaldi et al.3 (reviewing 243 abdominal CT scans) reported a higher frequency, 8.4%. Variation likely results from patient factors and the individual radiologist’s attention to incidental pulmonary findings. Rinaldi et al. suggested that up to 39% of abdominal CT scans include pulmonary nodules on independent review, raising the possibility of significant underreporting. In our study, we focused on pulmonary nodules included in the radiology report to tailor the relevance of our study to the hospital medicine community. We also included only those incidental nodules falling within the purview of the Fleischner Society criteria in order to analyze only findings with established follow-up guidelines.

The rate of pulmonary nodule documentation in our study was low overall (23%) but consistent with the literature. Collins et al.,4 for example, reported that only 17.7% of patients with trauma were notified of incidental CT findings by either the discharge summary or an appropriate specialist consultation. Various contributing factors can be hypothesized. First, incidental pulmonary nodules are discovered largely in the context of evaluation for other symptomatic conditions, which can overshadow their importance. Second, the lack of clear patient-friendly education materials regarding incidental pulmonary nodules can complicate discussions with patients. Third, many electronic health record (EHR) systems cannot automatically pull incidental findings into the discharge summary and instead rely on provider vigilance.

As our study does, the literature highlights the importance of the radiology report in communicating incidental findings. In a review of >1000 pulmonary angiographic CT studies, Blagev et al.9 reported an overall follow-up rate of 29% (28/96) among patients with incidental pulmonary nodules, but none of the 12 patients with pulmonary nodules mentioned in the body of the report (rather than in the summary headings) received adequate follow-up. Similarly, in Shuaib et al.,10 radiology reports that included follow-up recommendations were more likely to change patient treatment than reports without follow-up recommendations (70% vs 2%). However, our data also show that radiologist recommendations alone are insufficient to ensure adequate communication of incidental findings.

The literature regarding the most cost-effective means of addressing this quality gap is limited. Some institutions have integrated their EHR systems to allow radiologists to flag incidental findings for auto-population in a dedicated section of the discharge summary. Although these efforts can be helpful, documentation alone does not save lives without appropriate follow-up and intervention. Some institutions have hired dedicated nursing staff as incidental finding coordinators. For high-risk incidental findings, Sperry et al.11 reported that hiring an incidental findings coordinator helped their level I trauma center achieve nearly complete documentation, patient notification, and confirmation of posthospital follow-up appointments. Such solutions, however, are labor-intensive and still rely on appropriate primary care follow-up.

Strengths of our study include its relatively large size and particular focus on the issues and decisions facing hospital medicine providers. By focusing on incidental pulmonary nodules reported on abdominal CT, and excluding patients with concurrent chest CT, we avoided including patients with symptomatic or previously identified pulmonary findings. Study limitations include the cross-sectional, retrospective design, which did not include follow-up data regarding such outcomes as rates of appropriate follow-up surveillance and subsequent lung cancer diagnoses. Our single-center study findings may not apply to all hospital practice settings, though they are consistent with the literature with comparison data.

Our study results highlight the need for a multidisciplinary systems-based approach to incidental pulmonary nodule documentation, communication, and follow-up surveillance.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Armao D, Smith JK. Overuse of computed tomography and the onslaught of incidental findings. N C Med J. 2014;75(2):127. PubMed

2. Gould MK, Tang T, Liu IL, et al. Recent trends in the identification of incidental pulmonary nodules. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(10):1208-1214. PubMed

3. Rinaldi MF, Bartalena T, Giannelli G, et al. Incidental lung nodules on CT examinations of the abdomen: prevalence and reporting rates in the PACS era. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74(3):e84-e88. PubMed

4. Collins CE, Cherng N, McDade T, et al. Improving patient notification of solid abdominal viscera incidental findings with a standardized protocol. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2015;9(1):1. PubMed

5. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. PubMed

6. Swensen SJ, Silverstein MD, Ilstrup DM, Schleck CD, Edell ES. The probability of malignancy in solitary pulmonary nodules. Application to small radiologically indeterminate nodules. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(8):849-855. PubMed

7. Wu CC, Cronin CG, Chu JT, et al. Incidental pulmonary nodules detected on abdominal computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2012;36(6):641-645. PubMed

8. Alpert JB, Fantauzzi JP, Melamud K, Greenwood H, Naidich DP, Ko JP. Clinical significance of lung nodules reported on abdominal CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(4):793-799. PubMed

9. Blagev DP, Lloyd JF, Conner K, et al. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules and the radiology report. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11(4):378-383. PubMed

10. Shuaib W, Johnson JO, Salastekar N, Maddu KK, Khosa F. Incidental findings detected on abdomino-pelvic multidetector computed tomography performed in the acute setting [published correction appears in Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(7):811. Waqas, Shuaib (corrected to Shuaib, Waqas)]. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(1):36-39. PubMed

11. Sperry JL, Massaro MS, Collage RD, et al. Incidental radiographic findings after injury: dedicated attention results in improved capture, documentation, and management. Surgery. 2010;148(4):618-624. PubMed

1. Armao D, Smith JK. Overuse of computed tomography and the onslaught of incidental findings. N C Med J. 2014;75(2):127. PubMed

2. Gould MK, Tang T, Liu IL, et al. Recent trends in the identification of incidental pulmonary nodules. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(10):1208-1214. PubMed

3. Rinaldi MF, Bartalena T, Giannelli G, et al. Incidental lung nodules on CT examinations of the abdomen: prevalence and reporting rates in the PACS era. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74(3):e84-e88. PubMed

4. Collins CE, Cherng N, McDade T, et al. Improving patient notification of solid abdominal viscera incidental findings with a standardized protocol. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2015;9(1):1. PubMed

5. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. PubMed

6. Swensen SJ, Silverstein MD, Ilstrup DM, Schleck CD, Edell ES. The probability of malignancy in solitary pulmonary nodules. Application to small radiologically indeterminate nodules. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(8):849-855. PubMed

7. Wu CC, Cronin CG, Chu JT, et al. Incidental pulmonary nodules detected on abdominal computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2012;36(6):641-645. PubMed

8. Alpert JB, Fantauzzi JP, Melamud K, Greenwood H, Naidich DP, Ko JP. Clinical significance of lung nodules reported on abdominal CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(4):793-799. PubMed

9. Blagev DP, Lloyd JF, Conner K, et al. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules and the radiology report. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11(4):378-383. PubMed

10. Shuaib W, Johnson JO, Salastekar N, Maddu KK, Khosa F. Incidental findings detected on abdomino-pelvic multidetector computed tomography performed in the acute setting [published correction appears in Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(7):811. Waqas, Shuaib (corrected to Shuaib, Waqas)]. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(1):36-39. PubMed

11. Sperry JL, Massaro MS, Collage RD, et al. Incidental radiographic findings after injury: dedicated attention results in improved capture, documentation, and management. Surgery. 2010;148(4):618-624. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine