User login

The principles and practices of positive psychiatry are especially well-suited for work with children, adolescents, and families. Positive psychiatry is “the science and practice of psychiatry that seeks to understand and promote well-being through assessments and interventions aimed at enhancing positive psychosocial factors among people who have or are at risk for developing mental or physical illnesses.”1 The concept sprung from the momentum of positive psychology, which originated from Seligman et al.2 Importantly, the standards and techniques of positive psychiatry are designed as an enhancement, perhaps even as a completion, of more traditional psychiatry, rather than an alternative.3 They come from an acknowledgment that to be most effective as a mental health professional, it is important for clinicians to be experts in the full range of mental functioning.4,5

For most clinicians currently practicing “traditional” child and adolescent psychiatry, adapting at least some of the principles of positive psychiatry within one’s routine practice will not necessarily involve a radical transformation of thought or effort. Indeed, upon hearing about positive psychiatry principles, many nonprofessionals express surprise that this is not already considered routine practice. This article briefly outlines some of the basic tenets of positive child psychiatry and describes practical initial steps that can be readily incorporated into one’s day-to-day approach.

Defining pediatric positive psychiatry

There remains a fair amount of discussion and debate regarding what positive psychiatry is and isn’t, and how it fits into routine practice. While there is no official doctrine as to what “counts” as the practice of positive psychiatry, one can arguably divide most of its interventions into 2 main areas. The first is paying additional clinical attention to behaviors commonly associated with wellness or health promotion in youth. These include domains such as exercise, sleep habits, an authoritative parenting style, screen limits, and nutrition. The second area relates to specific techniques or procedures designed to cultivate positive emotions and mindsets; these often are referred to as positive psychology interventions (PPIs).6 Examples include gratitude exercises, practicing forgiveness, and activities that build optimism and hope. Many of the latter procedures share poorly defined boundaries with “tried and true” cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques, while others are more distinct to positive psychology and psychiatry. For both health promotion and PPIs, the goal of these interventions is to go beyond response and even remission for a patient to actual mental well-being, which is a construct that has also proven to be somewhat elusive and difficult to define. One well-described model by Seligman7 that has been gaining traction is the PERMA model, which breaks down well-being into 5 main components: positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment.

Positive psychiatry: The evidence base

One myth about positive psychiatry is that it involves the pursuit of fringe and scientifically suspect techniques that have fallen under the expanding umbrella of “wellness.” Sadly, numerous unscientific and ineffective remedies have been widely promoted under the guise of wellness, leaving many families and clinicians uncertain about which areas have a solid evidence base and which are scientifically on shakier ground. While the lines delineating what are often referred to as PPI and more traditional psychotherapeutic techniques are blurry, there is increasing evidence supporting the use of PPI.8 A recent meta-analysis indicated that these techniques have larger effect sizes for children and young adults compared to older adults.9 More research, however, is needed, particularly for youth with diagnosable mental health conditions and for younger children.10

The evidence supporting the role of wellness and health promotion in preventing and treating pediatric mental health conditions has a quite robust research base. For example, a recent randomized controlled trial found greater reductions in multiple areas of emotional-behavior problems in children treated in a primary care setting with a wellness and health promotion model (the Vermont Family Based Approach) compared to those in a control condition.11 Another study examining the course of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) showed a 62% reduction of diagnosis among children who met 7 of 9 health promotion recommendations in areas such as nutrition, physical activity, and screen time, compared to those who met just 1 to 3 of these recommendations.12 Techniques such as mindfulness also have been found to be useful for adolescents with anxiety disorders.13 While a full review of the evidence is beyond the scope of this article, it is fair to say that many health promotion areas (such as exercise, nutrition, sleep habits, positive parenting skills, and some types of mindfulness) have strong scientific support—arguably at a level that is comparable to or even exceeds that of the off-label use of many psychiatric medications. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has published a brief document that summarizes many age-related health promotion recommendations.14 The studies that underlie many of these recommendations contradict the misperception that wellness activities are only for already healthy individuals who want to become healthier, and show their utility for patients with more significant and chronic mental health conditions.

Incorporating core principles of positive psychiatry

Table 1 summarizes the core principles of positive child and adolescent psychiatry. There is no official procedure or certification one must complete to be considered a “positive psychiatrist,” and the term itself is somewhat debatable. Incorporating many of the principles of positive psychiatry into one’s daily routine does not necessitate a practice overhaul, and clinicians can integrate as many of these ideas as they deem clinically appropriate. That said, some adjustments to one’s perspective, approach, and workflow are likely needed, and the practice of positive psychiatry is arguably difficult to accomplish within the common “med check” model that emphasizes high volumes of short appointments that focus primarily on symptoms and adverse effects of medications.

Contrary to another misconception about positive psychiatry, working within a positive psychiatry framework does not involve encouraging patients to “put on a happy face” and ignore the very real suffering and trauma that many of them have experienced. Further, adhering to positive psychiatry does not entail abandoning the use of psychopharmacology (although careful prescribing is generally recommended) or applying gimmicks to superficially cover a person’s emotional pain.

Continue to: Rather, incorporating positive psychiatry...

Rather, incorporating positive psychiatry is best viewed as the creation of a supplementary toolbox that allows clinicians an expanded set of focus areas that can be used along with traditional psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy to help patients achieve a more robust and sustained response to treatment.4,5,15 The positive psychiatrist looks beyond the individual to examine a youth’s entire environment, and beyond areas of challenge to assess strengths, hopes, and aspirations.16 While many of these values are already in the formal description of a child psychiatrist, these priorities can take a back seat when trying to get through a busy day. For some, being a positive child psychiatrist means prescribing exercise rather than a sleep medication, assessing a child’s character strengths in addition to their behavioral challenges, or discussing the concept of parental warmth and how a struggling mother or father can replenish their tank when it feels like there is little left to give. It can mean reading literature on subjects such as happiness and optimal parenting practices in addition to depression and child maltreatment, and seeing oneself as an expert in mental health rather than just mental illness.

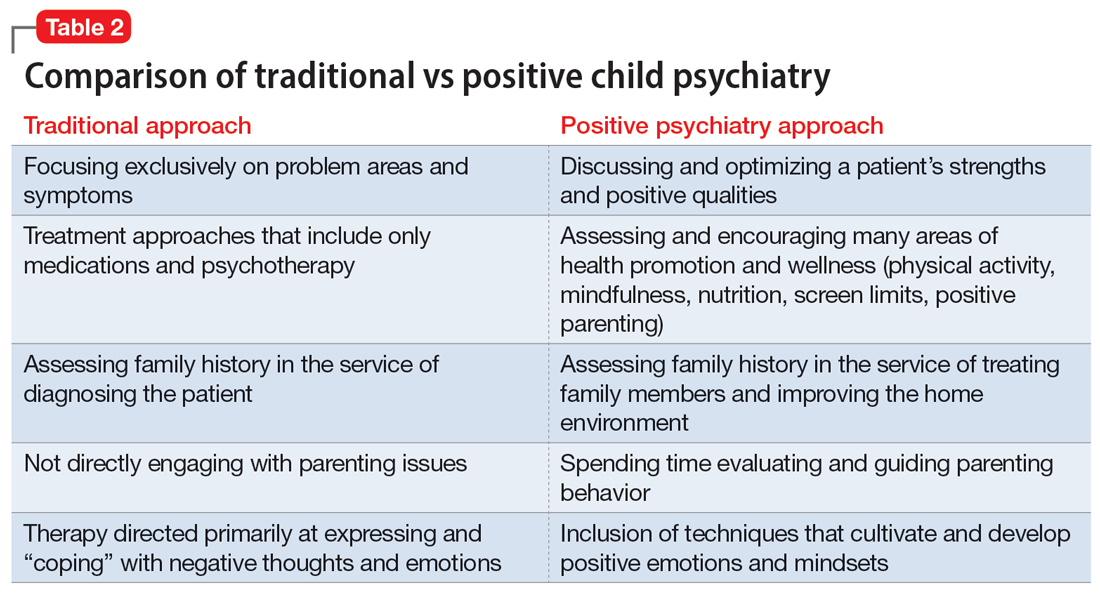

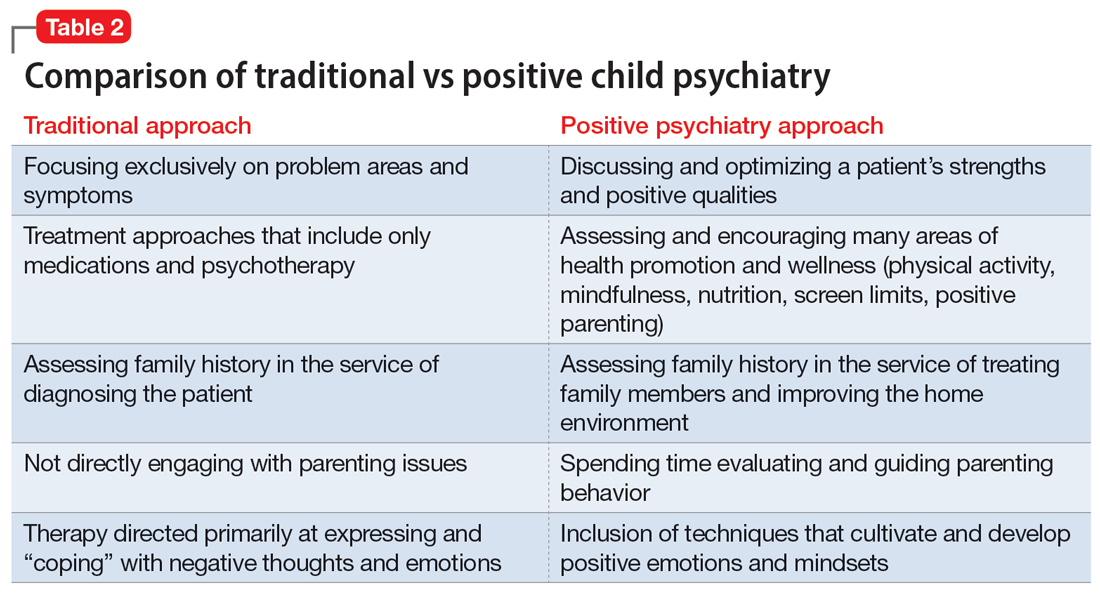

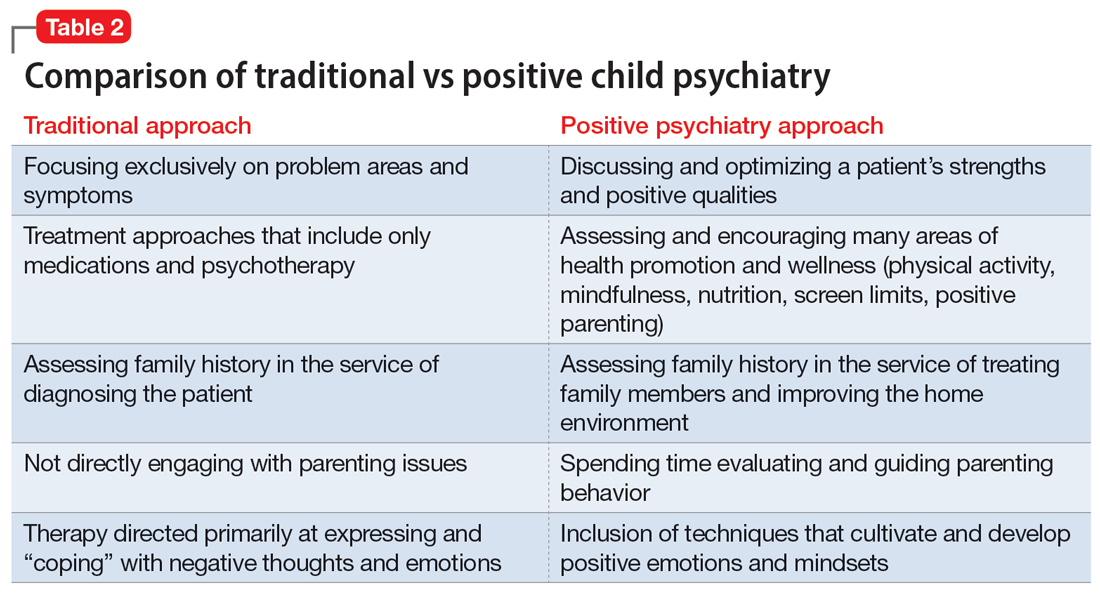

I have published a previous case example of positive psychiatry.17 Here I provide a brief vignette to further illustrate these concepts, and to compare traditional vs positive child psychiatry (Table 2).

CASE REPORT

Tyler, age 7, presents to a child and adolescent psychiatrist for refractory ADHD problems, continued defiance, and aggressive outbursts. Approximately 1 year ago, Tyler’s pediatrician had diagnosed him with fairly classic ADHD symptoms and prescribed long-acting methylphenidate. Tyler’s attention has improved somewhat at school, but there remains a significant degree of conflict and dysregulation at home. Tyler remains easily frustrated and is often very negative. The pediatrician is looking for additional treatment recommendations.

Traditional approach

The child psychiatrist assesses Tyler and gathers data from the patient, his parents, and his school. She confirms the diagnosis of ADHD, but in reviewing other potential conditions also discovers that Tyler meets DSM-5 criteria for oppositional defiant disorder. The clinician suspects there may also be a co-occurring learning disability and notices that Tyler has chronic difficulties getting to sleep. She also hypothesizes the stimulant medication is wearing off at about the time Tyler gets home from school. The psychiatrist recommends adding an immediate-release formulation of methylphenidate upon return from school, melatonin at night, a school psychoeducational assessment, and behavioral therapy for Tyler and his parents to focus on his disrespectful and oppositional behavior.

Three months later, there has been incremental improvement with the additional medication and a school individualized education plan. Tyler is also working with a therapist, who does some play therapy with Tyler and works on helping his parents create incentives for prosocial behavior, but progress has been slow and the amount of improvement in this area is minimal. Further, the initial positive effect of the melatonin on sleep has waned lately, and the parents now ask about “something stronger.”

Continue to: Positive psychiatry approach

Positive psychiatry approach

In addition to assessing problem areas and DSM-5 criteria, the psychiatrist assesses a number of other domains. She finds that most of the interaction between Tyler and his parents are negative to the point that his parents often just stay out of his way. She also discovers that Tyler does little in the way of structured activities and spends most of his time at home playing video games, sometimes well into the evening. He gets little to no physical activity outside of school. He also is a very selective eater and often skips breakfast entirely due to the usually chaotic home scene in the morning. A brief mental health screen of the parents further reveals that the mother would also likely meet criteria for ADHD, and the father may be experiencing depression.

The psychiatrist prescribes an additional immediate-release formulation stimulant for the afternoon but holds off on prescribing sleep medication. Instead, she discusses a plan in which Tyler can earn his screen time by reading or exercising, and urges the parents to do some regular physical activity together. She discusses the findings of her screenings of the parents and helps them get a more thorough assessment. She also encourages more family time and introduces them to the “rose, thorn, bud” exercise where each family member discusses a success, challenge, and opportunity of the day.

Three months later, Tyler’s attention and negativity have decreased. His increased physical activity has helped his sleep, and ADHD treatment for the mother has made the mornings much smoother, allowing Tyler to eat a regular breakfast. Both improvements contribute further to Tyler’s improved attention during the day. Challenges remain, but the increased positive family experiences are helping the parents feel less depleted. As a result, they engage with Tyler more productively, and he has responded with more confidence and enthusiasm.

A natural extension of traditional work

The principles and practices associated with positive psychiatry represent a natural and highly needed extension of traditional work within child and adolescent psychiatry. Its emphasis on health promotion activities, family functioning, parental mental health, and utilization of strengths align closely with the growing scientific knowledge base that supports the complex interplay between the many genetic and environmental factors that underlie mental and physical health across the lifespan. For most psychiatrists, incorporating these important concepts and approaches will not require a radical transformation of one’s outlook or methodology, although some adjustments to practice and knowledge base augmentations are often needed. Clinicians interested in supplementing their skill set and working toward becoming an expert in the full range of mental functioning are encouraged to begin taking some of the steps outlined in this article to further their proficiency in the emerging discipline of positive psychiatry.

Bottom Line

Positive psychiatry is an important development that complements traditional approaches to child and adolescent mental health treatment through health promotion and cultivation of positive emotions and qualities. Incorporating it into routine practice is well within reach.

Related Resources

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW, eds. Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015.

- Positive Psychology Center. University of Pennsylvania School of Arts and Sciences. https://ppc.sas.upenn.edu/

- Rettew DC. Building healthy brains: a brief tip sheet for parents and schools. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/Docs/resource_centers/schools/Wellness_Dev_Tips.pdf

Drug Brand Names

Methylphenidate extended-release • Concerta, Ritalin LA

1. Jeste DV, Palmer BW. Introduction: What is positive psychiatry? In: Jeste DV, Palmer BW, eds. Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015:1-16.

2. Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: an introduction. Am Psychol. 2000;55:5-14.

3. Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Rettew DC, et al. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:675-683.

4. Rettew DC. Better than better: the new focus on well-being in child psychiatry. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2019;28:127-135.

5. Rettew DC. Positive child psychiatry. In: Jeste DV, Palmer BW, eds. Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015:285-304.

6. Parks AC, Kleiman EM, Kashdan TB, et al. Positive psychotherapeutic and behavioral interventions. In: Jeste DV, Palmer BW, eds. Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015:147-165.

7. Seligman MEP. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. Simon & Shuster; 2012.

8. Brunwasser SM, Gillham JE, Kim ES. A meta-analytic review of the Penn Resiliency Program’s effect on depressive symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:1042-1054.

9. Carr A, Cullen K, Keeney C, et al. Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pos Psychol. 2021:16:749-769.

10. Benoit V, Gabola P. Effects of positive psychology interventions on the well-being of young children: a systematic literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:12065.

11. Ivanova MY, Hall A, Weinberger S, et al. The Vermont family based approach in primary care pediatrics: effects on children’s and parents’ emotional and behavioral problems and parents’ health-related quality of life. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. Published online March 4, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s10578-022-01329-4

12. Lowen OK, Maximova K, Ekwaru JP, et al. Adherence to life-style recommendations and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychosom Med. 2020;82:305-315.

13. Zhou X, Guo J, et al. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on anxiety symptoms in young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289:113002.

14. Rettew DC. Building health brains: a brief tip sheet for parents and schools. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Accessed May 11, 2022. https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/Docs/resource_centers/schools/Wellness_Dev_Tips.pdf

15. Pustilnik S. Adapting well-being into outpatient child psychiatry. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Clin N Am. 2019;28:221-235.

16. Schlechter AD, O’Brien KH, Stewart C. The positive assessment: a model for integrating well-being and strengths-based approaches into the child and adolescent psychiatry clinical evaluation. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Clin N Am. 2019;28:157-169.

17. Rettew DC. A family- and wellness-based approach to child emotional-behavioral problems. In: RF Summers, Jeste DV, eds. Positive Psychiatry: A Casebook. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019:29-44.

The principles and practices of positive psychiatry are especially well-suited for work with children, adolescents, and families. Positive psychiatry is “the science and practice of psychiatry that seeks to understand and promote well-being through assessments and interventions aimed at enhancing positive psychosocial factors among people who have or are at risk for developing mental or physical illnesses.”1 The concept sprung from the momentum of positive psychology, which originated from Seligman et al.2 Importantly, the standards and techniques of positive psychiatry are designed as an enhancement, perhaps even as a completion, of more traditional psychiatry, rather than an alternative.3 They come from an acknowledgment that to be most effective as a mental health professional, it is important for clinicians to be experts in the full range of mental functioning.4,5

For most clinicians currently practicing “traditional” child and adolescent psychiatry, adapting at least some of the principles of positive psychiatry within one’s routine practice will not necessarily involve a radical transformation of thought or effort. Indeed, upon hearing about positive psychiatry principles, many nonprofessionals express surprise that this is not already considered routine practice. This article briefly outlines some of the basic tenets of positive child psychiatry and describes practical initial steps that can be readily incorporated into one’s day-to-day approach.

Defining pediatric positive psychiatry

There remains a fair amount of discussion and debate regarding what positive psychiatry is and isn’t, and how it fits into routine practice. While there is no official doctrine as to what “counts” as the practice of positive psychiatry, one can arguably divide most of its interventions into 2 main areas. The first is paying additional clinical attention to behaviors commonly associated with wellness or health promotion in youth. These include domains such as exercise, sleep habits, an authoritative parenting style, screen limits, and nutrition. The second area relates to specific techniques or procedures designed to cultivate positive emotions and mindsets; these often are referred to as positive psychology interventions (PPIs).6 Examples include gratitude exercises, practicing forgiveness, and activities that build optimism and hope. Many of the latter procedures share poorly defined boundaries with “tried and true” cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques, while others are more distinct to positive psychology and psychiatry. For both health promotion and PPIs, the goal of these interventions is to go beyond response and even remission for a patient to actual mental well-being, which is a construct that has also proven to be somewhat elusive and difficult to define. One well-described model by Seligman7 that has been gaining traction is the PERMA model, which breaks down well-being into 5 main components: positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment.

Positive psychiatry: The evidence base

One myth about positive psychiatry is that it involves the pursuit of fringe and scientifically suspect techniques that have fallen under the expanding umbrella of “wellness.” Sadly, numerous unscientific and ineffective remedies have been widely promoted under the guise of wellness, leaving many families and clinicians uncertain about which areas have a solid evidence base and which are scientifically on shakier ground. While the lines delineating what are often referred to as PPI and more traditional psychotherapeutic techniques are blurry, there is increasing evidence supporting the use of PPI.8 A recent meta-analysis indicated that these techniques have larger effect sizes for children and young adults compared to older adults.9 More research, however, is needed, particularly for youth with diagnosable mental health conditions and for younger children.10

The evidence supporting the role of wellness and health promotion in preventing and treating pediatric mental health conditions has a quite robust research base. For example, a recent randomized controlled trial found greater reductions in multiple areas of emotional-behavior problems in children treated in a primary care setting with a wellness and health promotion model (the Vermont Family Based Approach) compared to those in a control condition.11 Another study examining the course of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) showed a 62% reduction of diagnosis among children who met 7 of 9 health promotion recommendations in areas such as nutrition, physical activity, and screen time, compared to those who met just 1 to 3 of these recommendations.12 Techniques such as mindfulness also have been found to be useful for adolescents with anxiety disorders.13 While a full review of the evidence is beyond the scope of this article, it is fair to say that many health promotion areas (such as exercise, nutrition, sleep habits, positive parenting skills, and some types of mindfulness) have strong scientific support—arguably at a level that is comparable to or even exceeds that of the off-label use of many psychiatric medications. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has published a brief document that summarizes many age-related health promotion recommendations.14 The studies that underlie many of these recommendations contradict the misperception that wellness activities are only for already healthy individuals who want to become healthier, and show their utility for patients with more significant and chronic mental health conditions.

Incorporating core principles of positive psychiatry

Table 1 summarizes the core principles of positive child and adolescent psychiatry. There is no official procedure or certification one must complete to be considered a “positive psychiatrist,” and the term itself is somewhat debatable. Incorporating many of the principles of positive psychiatry into one’s daily routine does not necessitate a practice overhaul, and clinicians can integrate as many of these ideas as they deem clinically appropriate. That said, some adjustments to one’s perspective, approach, and workflow are likely needed, and the practice of positive psychiatry is arguably difficult to accomplish within the common “med check” model that emphasizes high volumes of short appointments that focus primarily on symptoms and adverse effects of medications.

Contrary to another misconception about positive psychiatry, working within a positive psychiatry framework does not involve encouraging patients to “put on a happy face” and ignore the very real suffering and trauma that many of them have experienced. Further, adhering to positive psychiatry does not entail abandoning the use of psychopharmacology (although careful prescribing is generally recommended) or applying gimmicks to superficially cover a person’s emotional pain.

Continue to: Rather, incorporating positive psychiatry...

Rather, incorporating positive psychiatry is best viewed as the creation of a supplementary toolbox that allows clinicians an expanded set of focus areas that can be used along with traditional psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy to help patients achieve a more robust and sustained response to treatment.4,5,15 The positive psychiatrist looks beyond the individual to examine a youth’s entire environment, and beyond areas of challenge to assess strengths, hopes, and aspirations.16 While many of these values are already in the formal description of a child psychiatrist, these priorities can take a back seat when trying to get through a busy day. For some, being a positive child psychiatrist means prescribing exercise rather than a sleep medication, assessing a child’s character strengths in addition to their behavioral challenges, or discussing the concept of parental warmth and how a struggling mother or father can replenish their tank when it feels like there is little left to give. It can mean reading literature on subjects such as happiness and optimal parenting practices in addition to depression and child maltreatment, and seeing oneself as an expert in mental health rather than just mental illness.

I have published a previous case example of positive psychiatry.17 Here I provide a brief vignette to further illustrate these concepts, and to compare traditional vs positive child psychiatry (Table 2).

CASE REPORT

Tyler, age 7, presents to a child and adolescent psychiatrist for refractory ADHD problems, continued defiance, and aggressive outbursts. Approximately 1 year ago, Tyler’s pediatrician had diagnosed him with fairly classic ADHD symptoms and prescribed long-acting methylphenidate. Tyler’s attention has improved somewhat at school, but there remains a significant degree of conflict and dysregulation at home. Tyler remains easily frustrated and is often very negative. The pediatrician is looking for additional treatment recommendations.

Traditional approach

The child psychiatrist assesses Tyler and gathers data from the patient, his parents, and his school. She confirms the diagnosis of ADHD, but in reviewing other potential conditions also discovers that Tyler meets DSM-5 criteria for oppositional defiant disorder. The clinician suspects there may also be a co-occurring learning disability and notices that Tyler has chronic difficulties getting to sleep. She also hypothesizes the stimulant medication is wearing off at about the time Tyler gets home from school. The psychiatrist recommends adding an immediate-release formulation of methylphenidate upon return from school, melatonin at night, a school psychoeducational assessment, and behavioral therapy for Tyler and his parents to focus on his disrespectful and oppositional behavior.

Three months later, there has been incremental improvement with the additional medication and a school individualized education plan. Tyler is also working with a therapist, who does some play therapy with Tyler and works on helping his parents create incentives for prosocial behavior, but progress has been slow and the amount of improvement in this area is minimal. Further, the initial positive effect of the melatonin on sleep has waned lately, and the parents now ask about “something stronger.”

Continue to: Positive psychiatry approach

Positive psychiatry approach

In addition to assessing problem areas and DSM-5 criteria, the psychiatrist assesses a number of other domains. She finds that most of the interaction between Tyler and his parents are negative to the point that his parents often just stay out of his way. She also discovers that Tyler does little in the way of structured activities and spends most of his time at home playing video games, sometimes well into the evening. He gets little to no physical activity outside of school. He also is a very selective eater and often skips breakfast entirely due to the usually chaotic home scene in the morning. A brief mental health screen of the parents further reveals that the mother would also likely meet criteria for ADHD, and the father may be experiencing depression.

The psychiatrist prescribes an additional immediate-release formulation stimulant for the afternoon but holds off on prescribing sleep medication. Instead, she discusses a plan in which Tyler can earn his screen time by reading or exercising, and urges the parents to do some regular physical activity together. She discusses the findings of her screenings of the parents and helps them get a more thorough assessment. She also encourages more family time and introduces them to the “rose, thorn, bud” exercise where each family member discusses a success, challenge, and opportunity of the day.

Three months later, Tyler’s attention and negativity have decreased. His increased physical activity has helped his sleep, and ADHD treatment for the mother has made the mornings much smoother, allowing Tyler to eat a regular breakfast. Both improvements contribute further to Tyler’s improved attention during the day. Challenges remain, but the increased positive family experiences are helping the parents feel less depleted. As a result, they engage with Tyler more productively, and he has responded with more confidence and enthusiasm.

A natural extension of traditional work

The principles and practices associated with positive psychiatry represent a natural and highly needed extension of traditional work within child and adolescent psychiatry. Its emphasis on health promotion activities, family functioning, parental mental health, and utilization of strengths align closely with the growing scientific knowledge base that supports the complex interplay between the many genetic and environmental factors that underlie mental and physical health across the lifespan. For most psychiatrists, incorporating these important concepts and approaches will not require a radical transformation of one’s outlook or methodology, although some adjustments to practice and knowledge base augmentations are often needed. Clinicians interested in supplementing their skill set and working toward becoming an expert in the full range of mental functioning are encouraged to begin taking some of the steps outlined in this article to further their proficiency in the emerging discipline of positive psychiatry.

Bottom Line

Positive psychiatry is an important development that complements traditional approaches to child and adolescent mental health treatment through health promotion and cultivation of positive emotions and qualities. Incorporating it into routine practice is well within reach.

Related Resources

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW, eds. Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015.

- Positive Psychology Center. University of Pennsylvania School of Arts and Sciences. https://ppc.sas.upenn.edu/

- Rettew DC. Building healthy brains: a brief tip sheet for parents and schools. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/Docs/resource_centers/schools/Wellness_Dev_Tips.pdf

Drug Brand Names

Methylphenidate extended-release • Concerta, Ritalin LA

The principles and practices of positive psychiatry are especially well-suited for work with children, adolescents, and families. Positive psychiatry is “the science and practice of psychiatry that seeks to understand and promote well-being through assessments and interventions aimed at enhancing positive psychosocial factors among people who have or are at risk for developing mental or physical illnesses.”1 The concept sprung from the momentum of positive psychology, which originated from Seligman et al.2 Importantly, the standards and techniques of positive psychiatry are designed as an enhancement, perhaps even as a completion, of more traditional psychiatry, rather than an alternative.3 They come from an acknowledgment that to be most effective as a mental health professional, it is important for clinicians to be experts in the full range of mental functioning.4,5

For most clinicians currently practicing “traditional” child and adolescent psychiatry, adapting at least some of the principles of positive psychiatry within one’s routine practice will not necessarily involve a radical transformation of thought or effort. Indeed, upon hearing about positive psychiatry principles, many nonprofessionals express surprise that this is not already considered routine practice. This article briefly outlines some of the basic tenets of positive child psychiatry and describes practical initial steps that can be readily incorporated into one’s day-to-day approach.

Defining pediatric positive psychiatry

There remains a fair amount of discussion and debate regarding what positive psychiatry is and isn’t, and how it fits into routine practice. While there is no official doctrine as to what “counts” as the practice of positive psychiatry, one can arguably divide most of its interventions into 2 main areas. The first is paying additional clinical attention to behaviors commonly associated with wellness or health promotion in youth. These include domains such as exercise, sleep habits, an authoritative parenting style, screen limits, and nutrition. The second area relates to specific techniques or procedures designed to cultivate positive emotions and mindsets; these often are referred to as positive psychology interventions (PPIs).6 Examples include gratitude exercises, practicing forgiveness, and activities that build optimism and hope. Many of the latter procedures share poorly defined boundaries with “tried and true” cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques, while others are more distinct to positive psychology and psychiatry. For both health promotion and PPIs, the goal of these interventions is to go beyond response and even remission for a patient to actual mental well-being, which is a construct that has also proven to be somewhat elusive and difficult to define. One well-described model by Seligman7 that has been gaining traction is the PERMA model, which breaks down well-being into 5 main components: positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment.

Positive psychiatry: The evidence base

One myth about positive psychiatry is that it involves the pursuit of fringe and scientifically suspect techniques that have fallen under the expanding umbrella of “wellness.” Sadly, numerous unscientific and ineffective remedies have been widely promoted under the guise of wellness, leaving many families and clinicians uncertain about which areas have a solid evidence base and which are scientifically on shakier ground. While the lines delineating what are often referred to as PPI and more traditional psychotherapeutic techniques are blurry, there is increasing evidence supporting the use of PPI.8 A recent meta-analysis indicated that these techniques have larger effect sizes for children and young adults compared to older adults.9 More research, however, is needed, particularly for youth with diagnosable mental health conditions and for younger children.10

The evidence supporting the role of wellness and health promotion in preventing and treating pediatric mental health conditions has a quite robust research base. For example, a recent randomized controlled trial found greater reductions in multiple areas of emotional-behavior problems in children treated in a primary care setting with a wellness and health promotion model (the Vermont Family Based Approach) compared to those in a control condition.11 Another study examining the course of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) showed a 62% reduction of diagnosis among children who met 7 of 9 health promotion recommendations in areas such as nutrition, physical activity, and screen time, compared to those who met just 1 to 3 of these recommendations.12 Techniques such as mindfulness also have been found to be useful for adolescents with anxiety disorders.13 While a full review of the evidence is beyond the scope of this article, it is fair to say that many health promotion areas (such as exercise, nutrition, sleep habits, positive parenting skills, and some types of mindfulness) have strong scientific support—arguably at a level that is comparable to or even exceeds that of the off-label use of many psychiatric medications. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry has published a brief document that summarizes many age-related health promotion recommendations.14 The studies that underlie many of these recommendations contradict the misperception that wellness activities are only for already healthy individuals who want to become healthier, and show their utility for patients with more significant and chronic mental health conditions.

Incorporating core principles of positive psychiatry

Table 1 summarizes the core principles of positive child and adolescent psychiatry. There is no official procedure or certification one must complete to be considered a “positive psychiatrist,” and the term itself is somewhat debatable. Incorporating many of the principles of positive psychiatry into one’s daily routine does not necessitate a practice overhaul, and clinicians can integrate as many of these ideas as they deem clinically appropriate. That said, some adjustments to one’s perspective, approach, and workflow are likely needed, and the practice of positive psychiatry is arguably difficult to accomplish within the common “med check” model that emphasizes high volumes of short appointments that focus primarily on symptoms and adverse effects of medications.

Contrary to another misconception about positive psychiatry, working within a positive psychiatry framework does not involve encouraging patients to “put on a happy face” and ignore the very real suffering and trauma that many of them have experienced. Further, adhering to positive psychiatry does not entail abandoning the use of psychopharmacology (although careful prescribing is generally recommended) or applying gimmicks to superficially cover a person’s emotional pain.

Continue to: Rather, incorporating positive psychiatry...

Rather, incorporating positive psychiatry is best viewed as the creation of a supplementary toolbox that allows clinicians an expanded set of focus areas that can be used along with traditional psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy to help patients achieve a more robust and sustained response to treatment.4,5,15 The positive psychiatrist looks beyond the individual to examine a youth’s entire environment, and beyond areas of challenge to assess strengths, hopes, and aspirations.16 While many of these values are already in the formal description of a child psychiatrist, these priorities can take a back seat when trying to get through a busy day. For some, being a positive child psychiatrist means prescribing exercise rather than a sleep medication, assessing a child’s character strengths in addition to their behavioral challenges, or discussing the concept of parental warmth and how a struggling mother or father can replenish their tank when it feels like there is little left to give. It can mean reading literature on subjects such as happiness and optimal parenting practices in addition to depression and child maltreatment, and seeing oneself as an expert in mental health rather than just mental illness.

I have published a previous case example of positive psychiatry.17 Here I provide a brief vignette to further illustrate these concepts, and to compare traditional vs positive child psychiatry (Table 2).

CASE REPORT

Tyler, age 7, presents to a child and adolescent psychiatrist for refractory ADHD problems, continued defiance, and aggressive outbursts. Approximately 1 year ago, Tyler’s pediatrician had diagnosed him with fairly classic ADHD symptoms and prescribed long-acting methylphenidate. Tyler’s attention has improved somewhat at school, but there remains a significant degree of conflict and dysregulation at home. Tyler remains easily frustrated and is often very negative. The pediatrician is looking for additional treatment recommendations.

Traditional approach

The child psychiatrist assesses Tyler and gathers data from the patient, his parents, and his school. She confirms the diagnosis of ADHD, but in reviewing other potential conditions also discovers that Tyler meets DSM-5 criteria for oppositional defiant disorder. The clinician suspects there may also be a co-occurring learning disability and notices that Tyler has chronic difficulties getting to sleep. She also hypothesizes the stimulant medication is wearing off at about the time Tyler gets home from school. The psychiatrist recommends adding an immediate-release formulation of methylphenidate upon return from school, melatonin at night, a school psychoeducational assessment, and behavioral therapy for Tyler and his parents to focus on his disrespectful and oppositional behavior.

Three months later, there has been incremental improvement with the additional medication and a school individualized education plan. Tyler is also working with a therapist, who does some play therapy with Tyler and works on helping his parents create incentives for prosocial behavior, but progress has been slow and the amount of improvement in this area is minimal. Further, the initial positive effect of the melatonin on sleep has waned lately, and the parents now ask about “something stronger.”

Continue to: Positive psychiatry approach

Positive psychiatry approach

In addition to assessing problem areas and DSM-5 criteria, the psychiatrist assesses a number of other domains. She finds that most of the interaction between Tyler and his parents are negative to the point that his parents often just stay out of his way. She also discovers that Tyler does little in the way of structured activities and spends most of his time at home playing video games, sometimes well into the evening. He gets little to no physical activity outside of school. He also is a very selective eater and often skips breakfast entirely due to the usually chaotic home scene in the morning. A brief mental health screen of the parents further reveals that the mother would also likely meet criteria for ADHD, and the father may be experiencing depression.

The psychiatrist prescribes an additional immediate-release formulation stimulant for the afternoon but holds off on prescribing sleep medication. Instead, she discusses a plan in which Tyler can earn his screen time by reading or exercising, and urges the parents to do some regular physical activity together. She discusses the findings of her screenings of the parents and helps them get a more thorough assessment. She also encourages more family time and introduces them to the “rose, thorn, bud” exercise where each family member discusses a success, challenge, and opportunity of the day.

Three months later, Tyler’s attention and negativity have decreased. His increased physical activity has helped his sleep, and ADHD treatment for the mother has made the mornings much smoother, allowing Tyler to eat a regular breakfast. Both improvements contribute further to Tyler’s improved attention during the day. Challenges remain, but the increased positive family experiences are helping the parents feel less depleted. As a result, they engage with Tyler more productively, and he has responded with more confidence and enthusiasm.

A natural extension of traditional work

The principles and practices associated with positive psychiatry represent a natural and highly needed extension of traditional work within child and adolescent psychiatry. Its emphasis on health promotion activities, family functioning, parental mental health, and utilization of strengths align closely with the growing scientific knowledge base that supports the complex interplay between the many genetic and environmental factors that underlie mental and physical health across the lifespan. For most psychiatrists, incorporating these important concepts and approaches will not require a radical transformation of one’s outlook or methodology, although some adjustments to practice and knowledge base augmentations are often needed. Clinicians interested in supplementing their skill set and working toward becoming an expert in the full range of mental functioning are encouraged to begin taking some of the steps outlined in this article to further their proficiency in the emerging discipline of positive psychiatry.

Bottom Line

Positive psychiatry is an important development that complements traditional approaches to child and adolescent mental health treatment through health promotion and cultivation of positive emotions and qualities. Incorporating it into routine practice is well within reach.

Related Resources

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW, eds. Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015.

- Positive Psychology Center. University of Pennsylvania School of Arts and Sciences. https://ppc.sas.upenn.edu/

- Rettew DC. Building healthy brains: a brief tip sheet for parents and schools. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/Docs/resource_centers/schools/Wellness_Dev_Tips.pdf

Drug Brand Names

Methylphenidate extended-release • Concerta, Ritalin LA

1. Jeste DV, Palmer BW. Introduction: What is positive psychiatry? In: Jeste DV, Palmer BW, eds. Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015:1-16.

2. Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: an introduction. Am Psychol. 2000;55:5-14.

3. Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Rettew DC, et al. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:675-683.

4. Rettew DC. Better than better: the new focus on well-being in child psychiatry. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2019;28:127-135.

5. Rettew DC. Positive child psychiatry. In: Jeste DV, Palmer BW, eds. Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015:285-304.

6. Parks AC, Kleiman EM, Kashdan TB, et al. Positive psychotherapeutic and behavioral interventions. In: Jeste DV, Palmer BW, eds. Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015:147-165.

7. Seligman MEP. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. Simon & Shuster; 2012.

8. Brunwasser SM, Gillham JE, Kim ES. A meta-analytic review of the Penn Resiliency Program’s effect on depressive symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:1042-1054.

9. Carr A, Cullen K, Keeney C, et al. Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pos Psychol. 2021:16:749-769.

10. Benoit V, Gabola P. Effects of positive psychology interventions on the well-being of young children: a systematic literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:12065.

11. Ivanova MY, Hall A, Weinberger S, et al. The Vermont family based approach in primary care pediatrics: effects on children’s and parents’ emotional and behavioral problems and parents’ health-related quality of life. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. Published online March 4, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s10578-022-01329-4

12. Lowen OK, Maximova K, Ekwaru JP, et al. Adherence to life-style recommendations and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychosom Med. 2020;82:305-315.

13. Zhou X, Guo J, et al. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on anxiety symptoms in young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289:113002.

14. Rettew DC. Building health brains: a brief tip sheet for parents and schools. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Accessed May 11, 2022. https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/Docs/resource_centers/schools/Wellness_Dev_Tips.pdf

15. Pustilnik S. Adapting well-being into outpatient child psychiatry. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Clin N Am. 2019;28:221-235.

16. Schlechter AD, O’Brien KH, Stewart C. The positive assessment: a model for integrating well-being and strengths-based approaches into the child and adolescent psychiatry clinical evaluation. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Clin N Am. 2019;28:157-169.

17. Rettew DC. A family- and wellness-based approach to child emotional-behavioral problems. In: RF Summers, Jeste DV, eds. Positive Psychiatry: A Casebook. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019:29-44.

1. Jeste DV, Palmer BW. Introduction: What is positive psychiatry? In: Jeste DV, Palmer BW, eds. Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015:1-16.

2. Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: an introduction. Am Psychol. 2000;55:5-14.

3. Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Rettew DC, et al. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:675-683.

4. Rettew DC. Better than better: the new focus on well-being in child psychiatry. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2019;28:127-135.

5. Rettew DC. Positive child psychiatry. In: Jeste DV, Palmer BW, eds. Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015:285-304.

6. Parks AC, Kleiman EM, Kashdan TB, et al. Positive psychotherapeutic and behavioral interventions. In: Jeste DV, Palmer BW, eds. Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015:147-165.

7. Seligman MEP. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. Simon & Shuster; 2012.

8. Brunwasser SM, Gillham JE, Kim ES. A meta-analytic review of the Penn Resiliency Program’s effect on depressive symptoms. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:1042-1054.

9. Carr A, Cullen K, Keeney C, et al. Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pos Psychol. 2021:16:749-769.

10. Benoit V, Gabola P. Effects of positive psychology interventions on the well-being of young children: a systematic literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:12065.

11. Ivanova MY, Hall A, Weinberger S, et al. The Vermont family based approach in primary care pediatrics: effects on children’s and parents’ emotional and behavioral problems and parents’ health-related quality of life. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. Published online March 4, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s10578-022-01329-4

12. Lowen OK, Maximova K, Ekwaru JP, et al. Adherence to life-style recommendations and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychosom Med. 2020;82:305-315.

13. Zhou X, Guo J, et al. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on anxiety symptoms in young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289:113002.

14. Rettew DC. Building health brains: a brief tip sheet for parents and schools. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Accessed May 11, 2022. https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/Docs/resource_centers/schools/Wellness_Dev_Tips.pdf

15. Pustilnik S. Adapting well-being into outpatient child psychiatry. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Clin N Am. 2019;28:221-235.

16. Schlechter AD, O’Brien KH, Stewart C. The positive assessment: a model for integrating well-being and strengths-based approaches into the child and adolescent psychiatry clinical evaluation. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Clin N Am. 2019;28:157-169.

17. Rettew DC. A family- and wellness-based approach to child emotional-behavioral problems. In: RF Summers, Jeste DV, eds. Positive Psychiatry: A Casebook. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019:29-44.