User login

Each year in late summer, the CDC publishes its recommendations for the prevention of influenza for the upcoming season. The severity of each influenza season varies and is difficult to predict—underscoring the need to provide maximal vaccine coverage for at-risk patient populations.

Hoping for the best, planning for the worst.

Over the past several decades, the annual number of influenza-related hospitalizations has varied from approximately 55,000 to 431,000,1 and the number of deaths from influenza has been as low as 3,349 and as high as 48,614.2 Infection rates are usually highest in children.

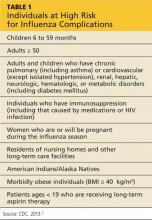

Complications, hospitalizations, and deaths are highest in adults ≥ 65, children < 2 years, and patients with medical conditions known to increase risk for influenza complications. Those at high risk of complications appear in Table 1.3

The main recommendations for this coming year are the same as those for last year, including vaccinating everyone ≥ 6 months of age without a contraindication, starting vaccinations as soon as vaccine is available, and continuing throughout the influenza season for those who need it.

What’s new this year

An increasing number of influenza vaccine products are available; although to date, their effectiveness (which was determined to be 56% for all vaccines used last influenza season)4 remains below what we would hope for. The CDC’s recommendations address these new types of vaccines, including ones that have four antigens instead of three, and use new terminology to describe the vaccines.3

New terminology reflects changing vaccine formulations.

Last influenza season there were two major categories of influenza vaccines: live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV). All products were produced using egg-culture methods and contained two influenza A antigen subtypes and oneB subtype.

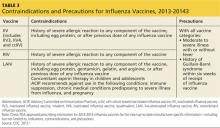

Several products this year include four antigens (two A subtypes and two B subtypes), and some are now produced with non–egg-culture methods. This has led to a new system of classification, with the term inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) replacing TIV. Table 2 lists the influenza vaccine categories and abbreviations. Table 33 lists the contraindications for the different vaccine types.

The new products include Flumist Quadrivalent (MedImmune), a quadrivalent LAIV (LAIV4); Fluarix Quadrivalent (GlaxoSmithKline), a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4); Flucelvax (Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics), a cell culture-based trivalent IIV (ccIIV3); and FluBlok (Protein Sciences), a trivalent recombinant hemagglutinin influenza vaccine (RIV3). Fluzone (Sanofi Pasteur), introduced last season in a trivalent formulation, is also available this season as a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4).

As a group, influenza vaccine products now offer three routes of administration: intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intranasal. There is currently no evidence that any route offers an advantage over another, and the CDC states no preference for any particular product or route of administration.

Mercury content is not a problem

Even though there is no scientific controversy over the safety of the mercury-containing preservative thimerosal, some patients still have doubts and may ask for a thimerosal-free product. The only influenza products that contain any thimerosal are those that come in multidose vials. A description of each influenza vaccine product, including thimerosal content, indicated ages, and routes of administration, can be found on the CDC’s Web site (www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm).3

Options for those with egg allergy

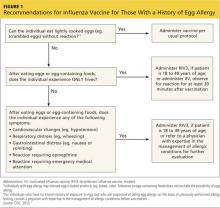

There is now a product, RIV3 (FluBlok), that is manufactured without the use of eggs. It can be used in those 18 to 49 years of age with a history of egg allergy of any severity. Since 2011, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has recommended that individuals with a history of mild egg allergy (those who experience only hives after egg exposure) may receive IIV, with additional safety precautions. Do not delay vaccination for these individuals if RIV is unavailable. Because of a lack of data demonstrating safety of LAIV for individuals with egg allergy, those allergic to eggs should receive RIV or IIV rather than LAIV.

Though the new ccIIV product, Flucelvax, is manufactured without the use of eggs, the seed viruses used to create the vaccine have been processed in eggs. The egg protein content in the vaccine is extremely low (< 50 femtograms [5 × 10-14 g] per 0.5-mL dose), but the CDC does not consider it egg free. Figure 1 (see page 32) depicts the recommendations for those with a history of egg allergy.3

Other interventions for influenza prevention

Vaccination is only one tool available to prevent morbidity and mortality from influenza. Antiviral chemoprevention and treatment and infection control practices can also be effective.

Antiviral chemoprevention is available for both pre- and post-exposure administration. In the past few years, the CDC has de-emphasized such use of antivirals for these indications out of concern for the supply of these agents and for the possibility that their use might lead to increased rates of viral resistance. Consider antiviral chemoprevention for those who have conditions that place them at risk for complications, and for those who are unvaccinated if they are at high risk for exposure to influenza (pre-exposure prophylaxis) or have been exposed (postexposure prophylaxis), if the medication can be started within 48 hours of exposure.

Another option for unvaccinated high-risk patients is vigilant symptom monitoring with early treatment for influenza symptoms. Chemoprophylaxis is recommended in addition to vaccination to control influenza outbreaks at institutions that house patients at high risk for complications of influenza. Details on recommended antivirals including doses and duration of treatment can be found in a 2011 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.5

Antiviral treatment. The CDC recommends antiviral treatment for anyone with suspected or confirmed influenza who has progressive, severe, or complicated illness or is hospitalized for his or her illness.5 Treatment is also recommended for outpatients with suspected or confirmed influenza who are at higher risk for influenza complications. This latter group includes those in Table 1, particularly children 6 to 59 months and adults ≥ 50. Start antiviral treatment within 48 hours of the first symptoms. For hospitalized patients, however, begin treatment at any point, regardless of duration of illness.

Infection control practices can prevent the spread of influenza in the health care setting and in the homes of those with influenza. These practices are also described on the CDC influenza Web site.6

References

1. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292:1333-1340.

2. CDC. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza–United States, 1976-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1057-1062.

3. CDC. Summary* recommendations: prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—(ACIP)—United States, 2013-14. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm. Accessed August 9, 2013.

4. CDC. Interim adjusted estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness–United States, February 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:119-123.

5. CDC. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(RR01):1-24. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6001a1.htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

6. CDC. Infection control in health care facilities. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/index.htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

Each year in late summer, the CDC publishes its recommendations for the prevention of influenza for the upcoming season. The severity of each influenza season varies and is difficult to predict—underscoring the need to provide maximal vaccine coverage for at-risk patient populations.

Hoping for the best, planning for the worst.

Over the past several decades, the annual number of influenza-related hospitalizations has varied from approximately 55,000 to 431,000,1 and the number of deaths from influenza has been as low as 3,349 and as high as 48,614.2 Infection rates are usually highest in children.

Complications, hospitalizations, and deaths are highest in adults ≥ 65, children < 2 years, and patients with medical conditions known to increase risk for influenza complications. Those at high risk of complications appear in Table 1.3

The main recommendations for this coming year are the same as those for last year, including vaccinating everyone ≥ 6 months of age without a contraindication, starting vaccinations as soon as vaccine is available, and continuing throughout the influenza season for those who need it.

What’s new this year

An increasing number of influenza vaccine products are available; although to date, their effectiveness (which was determined to be 56% for all vaccines used last influenza season)4 remains below what we would hope for. The CDC’s recommendations address these new types of vaccines, including ones that have four antigens instead of three, and use new terminology to describe the vaccines.3

New terminology reflects changing vaccine formulations.

Last influenza season there were two major categories of influenza vaccines: live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV). All products were produced using egg-culture methods and contained two influenza A antigen subtypes and oneB subtype.

Several products this year include four antigens (two A subtypes and two B subtypes), and some are now produced with non–egg-culture methods. This has led to a new system of classification, with the term inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) replacing TIV. Table 2 lists the influenza vaccine categories and abbreviations. Table 33 lists the contraindications for the different vaccine types.

The new products include Flumist Quadrivalent (MedImmune), a quadrivalent LAIV (LAIV4); Fluarix Quadrivalent (GlaxoSmithKline), a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4); Flucelvax (Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics), a cell culture-based trivalent IIV (ccIIV3); and FluBlok (Protein Sciences), a trivalent recombinant hemagglutinin influenza vaccine (RIV3). Fluzone (Sanofi Pasteur), introduced last season in a trivalent formulation, is also available this season as a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4).

As a group, influenza vaccine products now offer three routes of administration: intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intranasal. There is currently no evidence that any route offers an advantage over another, and the CDC states no preference for any particular product or route of administration.

Mercury content is not a problem

Even though there is no scientific controversy over the safety of the mercury-containing preservative thimerosal, some patients still have doubts and may ask for a thimerosal-free product. The only influenza products that contain any thimerosal are those that come in multidose vials. A description of each influenza vaccine product, including thimerosal content, indicated ages, and routes of administration, can be found on the CDC’s Web site (www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm).3

Options for those with egg allergy

There is now a product, RIV3 (FluBlok), that is manufactured without the use of eggs. It can be used in those 18 to 49 years of age with a history of egg allergy of any severity. Since 2011, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has recommended that individuals with a history of mild egg allergy (those who experience only hives after egg exposure) may receive IIV, with additional safety precautions. Do not delay vaccination for these individuals if RIV is unavailable. Because of a lack of data demonstrating safety of LAIV for individuals with egg allergy, those allergic to eggs should receive RIV or IIV rather than LAIV.

Though the new ccIIV product, Flucelvax, is manufactured without the use of eggs, the seed viruses used to create the vaccine have been processed in eggs. The egg protein content in the vaccine is extremely low (< 50 femtograms [5 × 10-14 g] per 0.5-mL dose), but the CDC does not consider it egg free. Figure 1 (see page 32) depicts the recommendations for those with a history of egg allergy.3

Other interventions for influenza prevention

Vaccination is only one tool available to prevent morbidity and mortality from influenza. Antiviral chemoprevention and treatment and infection control practices can also be effective.

Antiviral chemoprevention is available for both pre- and post-exposure administration. In the past few years, the CDC has de-emphasized such use of antivirals for these indications out of concern for the supply of these agents and for the possibility that their use might lead to increased rates of viral resistance. Consider antiviral chemoprevention for those who have conditions that place them at risk for complications, and for those who are unvaccinated if they are at high risk for exposure to influenza (pre-exposure prophylaxis) or have been exposed (postexposure prophylaxis), if the medication can be started within 48 hours of exposure.

Another option for unvaccinated high-risk patients is vigilant symptom monitoring with early treatment for influenza symptoms. Chemoprophylaxis is recommended in addition to vaccination to control influenza outbreaks at institutions that house patients at high risk for complications of influenza. Details on recommended antivirals including doses and duration of treatment can be found in a 2011 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.5

Antiviral treatment. The CDC recommends antiviral treatment for anyone with suspected or confirmed influenza who has progressive, severe, or complicated illness or is hospitalized for his or her illness.5 Treatment is also recommended for outpatients with suspected or confirmed influenza who are at higher risk for influenza complications. This latter group includes those in Table 1, particularly children 6 to 59 months and adults ≥ 50. Start antiviral treatment within 48 hours of the first symptoms. For hospitalized patients, however, begin treatment at any point, regardless of duration of illness.

Infection control practices can prevent the spread of influenza in the health care setting and in the homes of those with influenza. These practices are also described on the CDC influenza Web site.6

References

1. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292:1333-1340.

2. CDC. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza–United States, 1976-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1057-1062.

3. CDC. Summary* recommendations: prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—(ACIP)—United States, 2013-14. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm. Accessed August 9, 2013.

4. CDC. Interim adjusted estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness–United States, February 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:119-123.

5. CDC. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(RR01):1-24. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6001a1.htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

6. CDC. Infection control in health care facilities. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/index.htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

Each year in late summer, the CDC publishes its recommendations for the prevention of influenza for the upcoming season. The severity of each influenza season varies and is difficult to predict—underscoring the need to provide maximal vaccine coverage for at-risk patient populations.

Hoping for the best, planning for the worst.

Over the past several decades, the annual number of influenza-related hospitalizations has varied from approximately 55,000 to 431,000,1 and the number of deaths from influenza has been as low as 3,349 and as high as 48,614.2 Infection rates are usually highest in children.

Complications, hospitalizations, and deaths are highest in adults ≥ 65, children < 2 years, and patients with medical conditions known to increase risk for influenza complications. Those at high risk of complications appear in Table 1.3

The main recommendations for this coming year are the same as those for last year, including vaccinating everyone ≥ 6 months of age without a contraindication, starting vaccinations as soon as vaccine is available, and continuing throughout the influenza season for those who need it.

What’s new this year

An increasing number of influenza vaccine products are available; although to date, their effectiveness (which was determined to be 56% for all vaccines used last influenza season)4 remains below what we would hope for. The CDC’s recommendations address these new types of vaccines, including ones that have four antigens instead of three, and use new terminology to describe the vaccines.3

New terminology reflects changing vaccine formulations.

Last influenza season there were two major categories of influenza vaccines: live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) and trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV). All products were produced using egg-culture methods and contained two influenza A antigen subtypes and oneB subtype.

Several products this year include four antigens (two A subtypes and two B subtypes), and some are now produced with non–egg-culture methods. This has led to a new system of classification, with the term inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) replacing TIV. Table 2 lists the influenza vaccine categories and abbreviations. Table 33 lists the contraindications for the different vaccine types.

The new products include Flumist Quadrivalent (MedImmune), a quadrivalent LAIV (LAIV4); Fluarix Quadrivalent (GlaxoSmithKline), a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4); Flucelvax (Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics), a cell culture-based trivalent IIV (ccIIV3); and FluBlok (Protein Sciences), a trivalent recombinant hemagglutinin influenza vaccine (RIV3). Fluzone (Sanofi Pasteur), introduced last season in a trivalent formulation, is also available this season as a quadrivalent IIV (IIV4).

As a group, influenza vaccine products now offer three routes of administration: intramuscular, subcutaneous, and intranasal. There is currently no evidence that any route offers an advantage over another, and the CDC states no preference for any particular product or route of administration.

Mercury content is not a problem

Even though there is no scientific controversy over the safety of the mercury-containing preservative thimerosal, some patients still have doubts and may ask for a thimerosal-free product. The only influenza products that contain any thimerosal are those that come in multidose vials. A description of each influenza vaccine product, including thimerosal content, indicated ages, and routes of administration, can be found on the CDC’s Web site (www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm).3

Options for those with egg allergy

There is now a product, RIV3 (FluBlok), that is manufactured without the use of eggs. It can be used in those 18 to 49 years of age with a history of egg allergy of any severity. Since 2011, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has recommended that individuals with a history of mild egg allergy (those who experience only hives after egg exposure) may receive IIV, with additional safety precautions. Do not delay vaccination for these individuals if RIV is unavailable. Because of a lack of data demonstrating safety of LAIV for individuals with egg allergy, those allergic to eggs should receive RIV or IIV rather than LAIV.

Though the new ccIIV product, Flucelvax, is manufactured without the use of eggs, the seed viruses used to create the vaccine have been processed in eggs. The egg protein content in the vaccine is extremely low (< 50 femtograms [5 × 10-14 g] per 0.5-mL dose), but the CDC does not consider it egg free. Figure 1 (see page 32) depicts the recommendations for those with a history of egg allergy.3

Other interventions for influenza prevention

Vaccination is only one tool available to prevent morbidity and mortality from influenza. Antiviral chemoprevention and treatment and infection control practices can also be effective.

Antiviral chemoprevention is available for both pre- and post-exposure administration. In the past few years, the CDC has de-emphasized such use of antivirals for these indications out of concern for the supply of these agents and for the possibility that their use might lead to increased rates of viral resistance. Consider antiviral chemoprevention for those who have conditions that place them at risk for complications, and for those who are unvaccinated if they are at high risk for exposure to influenza (pre-exposure prophylaxis) or have been exposed (postexposure prophylaxis), if the medication can be started within 48 hours of exposure.

Another option for unvaccinated high-risk patients is vigilant symptom monitoring with early treatment for influenza symptoms. Chemoprophylaxis is recommended in addition to vaccination to control influenza outbreaks at institutions that house patients at high risk for complications of influenza. Details on recommended antivirals including doses and duration of treatment can be found in a 2011 issue of Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.5

Antiviral treatment. The CDC recommends antiviral treatment for anyone with suspected or confirmed influenza who has progressive, severe, or complicated illness or is hospitalized for his or her illness.5 Treatment is also recommended for outpatients with suspected or confirmed influenza who are at higher risk for influenza complications. This latter group includes those in Table 1, particularly children 6 to 59 months and adults ≥ 50. Start antiviral treatment within 48 hours of the first symptoms. For hospitalized patients, however, begin treatment at any point, regardless of duration of illness.

Infection control practices can prevent the spread of influenza in the health care setting and in the homes of those with influenza. These practices are also described on the CDC influenza Web site.6

References

1. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA. 2004;292:1333-1340.

2. CDC. Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza–United States, 1976-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1057-1062.

3. CDC. Summary* recommendations: prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—(ACIP)—United States, 2013-14. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/acip/2013-summary-recommendations.htm. Accessed August 9, 2013.

4. CDC. Interim adjusted estimates of seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness–United States, February 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:119-123.

5. CDC. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(RR01):1-24. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr6001a1.htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.

6. CDC. Infection control in health care facilities. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/index.htm. Accessed July 2, 2013.