User login

This centennial year update focuses primarily on immunization, but also reviews epidemiology, transmission, and treatment.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

2017–2018 was a bad season

The 2017–2018 influenza epidemic was memorable, dominated by influenza A(H3N2) viruses with morbidity and mortality rates approaching pandemic numbers. It lasted 19 weeks, killed more people than any other epidemic since 2010, particularly children, and was associated with 30,453 hospitalizations—almost twice the previous season high in some parts of the United States.2

Regrettably, 171 unvaccinated children died during 2017–2018, accounting for almost 80% of deaths.2 The mean age of the children who died was 7.1 years; 51% had at least 1 underlying medical condition placing them at risk for influenza-related complications, and 57% died after hospitalization.2

Recent estimates of the incidence of symptomatic influenza among all ages ranged from 3% to 11%, which is slightly lower than historical estimates. The rates were higher for children under age 18 than for adults.3 Interestingly, influenza A(H3N2) accounted for 50% of cases of non-mumps viral parotitis during the 2014–2015 influenza season in the United States.4

Influenza C exists but is rare

Influenza A and B account for almost all influenza-related outpatient visits and hospitalizations. Surveillance data from May 2013 through December 2016 showed that influenza C accounts for 0.5% of influenza-related outpatient visits and hospitalizations, particularly affecting children ages 6 to 24 months. Medical comorbidities and copathogens were seen in all patients requiring intensive care and in most hospitalizations.5 Diagnostic tests for influenza C are not widely available.

Dogs and cats: Factories for new flu strains?

While pigs and birds are the major reservoirs of influenza viral genetic diversity from which infection is transmitted to humans, dogs and cats have recently emerged as possible sources of novel reassortant influenza A.6 With their frequent close contact with humans, our pets may prove to pose a significant threat.

Obesity a risk factor for influenza

Obesity emerged as a risk factor for severe influenza in the 2009 pandemic. Recent data also showed that obesity increases the duration of influenza A virus shedding, thus increasing duration of contagiousness.7

Influenza a cardiovascular risk factor

Previous data showed that influenza was a risk factor for cardiovascular events. Two recent epidemiologic studies from the United Kingdom showed that laboratory-confirmed influenza was associated with higher rates of myocardial infarction and stroke for up to 4 weeks.8,9

Which strain is the biggest threat?

Predicting which emerging influenza serotype may cause the next pandemic is difficult, but influenza A(H7N9), which had not infected humans until 2013 but has since infected about 1,600 people in China and killed 37% of them, appears to have the greatest potential.10

National influenza surveillance programs and influenza-related social media applications have been developed and may get a boost from technology. A smartphone equipped with a temperature sensor can instantly detect one’s temperature with great precision. A 2018 study suggested that a smartphone-driven thermometry application correlated well with national influenza-like illness activity and improved its forecast in real time and up to 3 weeks in advance.11

TRANSMISSION

Humidity may not block transmission

Animal studies have suggested that humidity in the air interferes with transmission of airborne influenza virus, partially from biologic inactivation. But when a recent study used humidity-controlled chambers to investigate the stability of the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus in suspended aerosols and stationary droplets, the virus remained infectious in aerosols across a wide range of relative humidities, challenging the common belief that humidity destabilizes respiratory viruses in aerosols.12

One sick passenger may not infect the whole plane

Transmission of respiratory viruses on airplane flights has long been considered a potential avenue for spreading influenza. However, a recent study that monitored movements of individuals on 10 transcontinental US flights and simulated inflight transmission based on these data showed a low probability of direct transmission, except for passengers seated in close proximity to an infectious passenger.13

WHAT’S IN THE NEW FLU SHOT?

The 2018–2019 quadrivalent vaccine for the Northern Hemisphere14 contains the following strains:

- A/Michigan/45/2015 A(H1N1)pdm09-like virus

- A/Singapore/INFIMH-16-0019/2016 (H3N2)-like virus

- B/Colorado/06/2017-like virus (Victoria lineage)

- B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus (Yamagata lineage).

The A(H3N2) (Singapore) and B/Victoria lineage components are new this year. The A(H3N2) strain was the main cause of the 2018 influenza epidemic in the Southern Hemisphere.

The quadrivalent live-attenuated vaccine, which was not recommended during the 2016–2017 and 2017–2018 influenza seasons, has made a comeback and is recommended for the 2018–2019 season in people for whom it is appropriate based on age and comorbidities.15 Although it was effective against influenza B and A(H3N2) viruses, it was less effective against the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09-like viruses during the 2013–2014 and 2015–2016 seasons.

A/Slovenia/2903/2015, the new A(H1N1)pdm09-like virus included in the 2018–2019 quadrivalent live-attenuated vaccine, is significantly more immunogenic than its predecessor, A/Bolivia/559/2013, but its clinical effectiveness remains to be seen.

PROMOTING VACCINATION

How effective is it?

Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the 2017–2018 influenza season was 36% overall, 67% against A(H1N1), 42% against influenza B, and 25% against A(H3N2).16 It is estimated that influenza vaccine prevents 300 to 4,000 deaths annually in the United States alone.17

A 2018 Cochrane review17 concluded that vaccination reduced the incidence of influenza by about half, with 2.3% of the population contracting the flu without vaccination compared with 0.9% with vaccination (risk ratio 0.41, 95% confidence interval 0.36–0.47). The same review found that 71 healthy adults need to be vaccinated to prevent 1 from experiencing influenza, and 29 to prevent 1 influenza-like illness.

Several recent studies showed that influenza vaccine effectiveness varied based on age and influenza serotype, with higher effectiveness in people ages 5 to 17 and ages 18 to 64 than in those age 65 and older.18–20 A mathematical model of influenza transmission and vaccination in the United States determined that even relatively low-efficacy influenza vaccines can be very useful if optimally distributed across age groups.21

Vaccination rates are low, and ‘antivaxxers’ are on the rise

Although the influenza vaccine is recommended in the United States for all people age 6 months and older regardless of the state of their health, vaccination rates remain low. In 2016, only 37% of employed adults were vaccinated. The highest rate was for government employees (45%), followed by private employees (36%), followed by the self-employed (30%).22

A national goal is to immunize 80% of all Americans and 90% of at-risk populations (which include children and the elderly).23 The number of US hospitals that require their employees to be vaccinated increased from 37.1% in 2013 to 61.4% in 2017.24 Regrettably, as of March 2018, 14 lawsuits addressing religious objections to hospital influenza vaccination mandates have been filed.25

Despite hundreds of studies demonstrating the efficacy, safety, and cost savings of influenza vaccination, the antivaccine movement has been growing in the United States and worldwide.26 All US states except West Virginia, Mississippi, and California allow nonmedical exemptions from vaccination based on religious or personal belief.27 Several US metropolitan areas represent “hot spots” for these exemptions.28 This may render such areas vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases, including influenza.

Herd immunity: We’re all in this together

Some argue that the potential adverse effects and the cost of vaccination outweigh the benefits, but the protective benefits of herd immunity are significant for those with comorbidities or compromised immunity.

Educating the public about herd immunity and local influenza vaccination uptake increases people’s willingness to be vaccinated.29 A key educational point is that at least 70% of a community needs to be vaccinated to prevent community outbreaks; this protects everyone, including those who do not mount a protective antibody response to influenza vaccination and those who are not vaccinated.

DOES ANNUAL VACCINATION BLUNT ITS EFFECTIVENESS?

Some studies from the 1970s and 1980s raised concern over a possible negative effect of annual influenza vaccination on vaccine effectiveness. The “antigenic distance hypothesis” holds that vaccine effectiveness is influenced by antigenic similarity between the previous season’s vaccine serotypes and the epidemic serotypes, as well as the antigenic similarity between the serotypes of the current and previous seasons.

A meta-analysis of studies from 2010 through 2015 showed significant inconsistencies in repeat vaccination effects within and between seasons and serotypes. It also showed that vaccine effectiveness may be influenced by more than 1 previous season, particularly for influenza A(H3N2), in which repeated vaccination can blunt the hemagglutinin antibody response.30

A study from Japan showed that people who needed medical attention for influenza in the previous season were at lower risk of a similar event in the current season.31 Prior-season influenza vaccination reduced current-season vaccine effectiveness only in those who did not have medically attended influenza in the prior season. This suggests that infection is more immunogenic than vaccination, but only against the serotype causing the infection and not the other serotypes included in the vaccine.

An Australian study showed that annual influenza vaccination did not decrease vaccine effectiveness against influenza-associated hospitalization. Rather, effectiveness increased by about 15% in those vaccinated in both current and previous seasons compared with those vaccinated in either season alone.32

European investigators showed that repeated seasonal influenza vaccination in the elderly prevented the need for hospitalization due to influenza A(H3N2) and B, but not A(H1N1)pdm09.33

VACCINATION IN SPECIAL POPULATIONS

High-dose vaccine for older adults

The high-dose influenza vaccine has been licensed since 2009 for use in the United States for people ages 65 and older.

Recent studies confirmed that high-dose vaccine is more effective than standard-dose vaccine in veterans34 and US Medicare beneficiaries.35

The high-dose vaccine is rapidly becoming the primary vaccine given to people ages 65 and older in retail pharmacies, where vaccination begins earlier in the season than in providers’ offices.36 Some studies have shown that the standard-dose vaccine wanes in effectiveness toward the end of the influenza season (particularly if the season is long) if it is given very early. It remains to be seen whether the same applies to the high-dose influenza vaccine.

Some advocate twice-annual influenza vaccination, particularly for older adults living in tropical and subtropical areas, where influenza seasons are more prolonged. However, a recently published study observed reductions in influenza-specific hemagglutination inhibition and cell-mediated immunity after twice-annual vaccination.37

Vaccination is beneficial during pregnancy

Many studies have shown the value of influenza vaccination during pregnancy for both mothers and their infants.

One recently published study showed that 18% of infants who developed influenza required hospitalization.38 In that study, prenatal and postpartum maternal influenza vaccination decreased the odds of influenza in infants by 61% and 53%, respectively.

Another study showed that vaccine effectiveness did not vary by gestational age at vaccination.39

Some studies have shown that influenza virus infection can increase susceptibility to certain bacterial infections. A post hoc analysis of an influenza vaccination study in pregnant women suggested that the vaccine was also associated with decreased rates of pertussis in these women.40

Factors that make vaccination less effective

Several factors including age-related frailty and iatrogenic and disease-related immunosuppression can affect vaccine effectiveness.

Frailty. A recent study showed that vaccine effectiveness was 77.6% in nonfrail older adults but only 58.7% in frail older adults.41

Immunosuppression. Temporary discontinuation of methotrexate for 2 weeks after influenza vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis improves vaccine immunogenicity without precipitating disease flare.42 Solid-organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients who received influenza vaccine were less likely to develop pneumonia and require intensive care unit admission.43

The high-dose influenza vaccine is more immunogenic than the standard-dose vaccine in solid-organ transplant recipients.44

Statins are widely prescribed and have recently been associated with reduced influenza vaccine effectiveness against medically attended acute respiratory illness, but their benefits in preventing cardiovascular events outweigh this risk.45

FUTURE VACCINE CONSIDERATIONS

Moving away from eggs

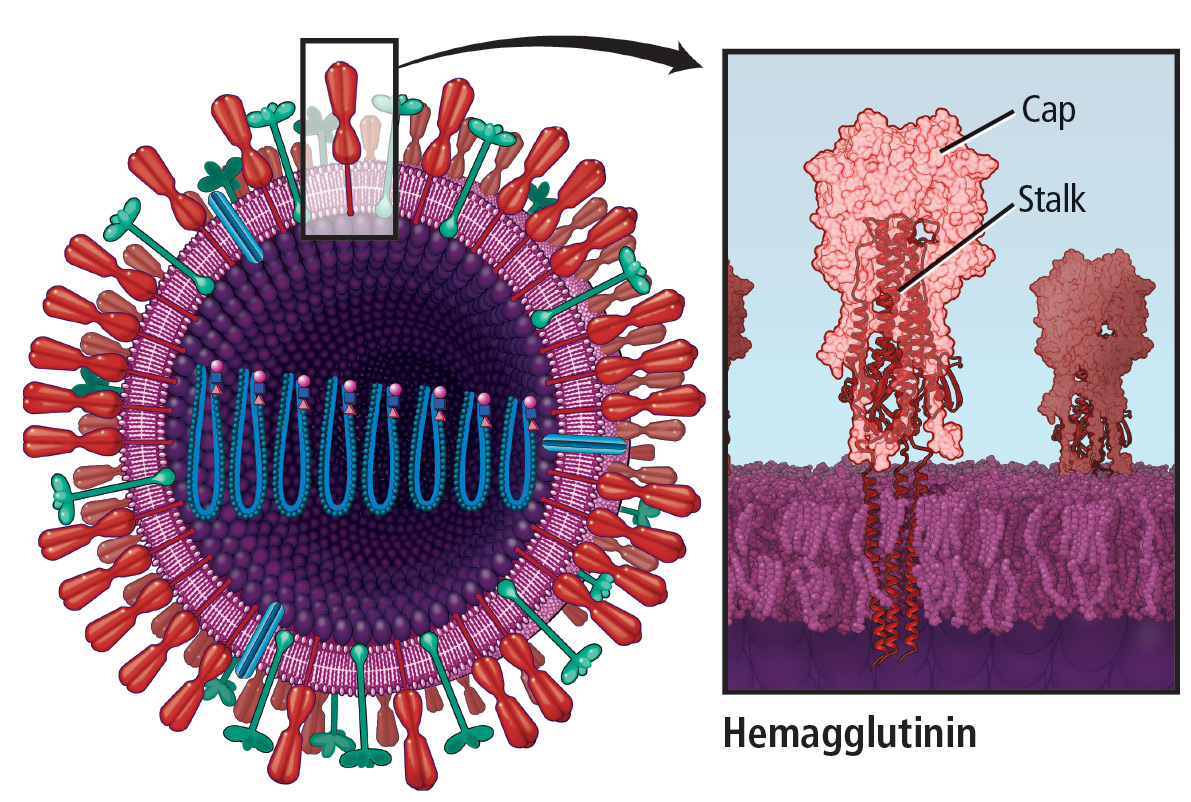

During the annual egg-based production process, which takes several months, the influenza vaccine acquires antigenic changes that allow replication in eggs, particularly in the hemagglutinin protein, which mediates receptor binding. This process of egg adaptation may cause antigenic changes that decrease vaccine effectiveness against circulating viruses.

The cell-based baculovirus influenza vaccine grown in dog kidney cells has higher antigenic content and is not subject to the limitations of egg-based vaccine, although it still requires annual updates. A recombinant influenza vaccine reduces the probability of influenza-like illness by 30% compared with the egg-based influenza vaccine, but also still requires annual updates.46 The market share of these non-egg-based vaccines is small, and thus their effectiveness has yet to be demonstrated.

The US Department of Defense administered the cell-based influenza vaccine to about one-third of Armed Forces personnel, their families, and retirees in the 2017–2018 influenza seasons, and data on its effectiveness are expected in the near future.47

A universal vaccine would be ideal

The quest continues for a universal influenza vaccine, one that remains protective for several years and does not require annual updates.48 Such a vaccine would protect against seasonal epidemic influenza drift variants and pandemic strains. More people could likely be persuaded to be vaccinated once rather than every year.

An ideal universal vaccine would be suitable for all age groups, at least 75% effective against symptomatic influenza virus infection, protective against all influenza A viruses (influenza A, not B, causes pandemics and seasonal epidemics), and durable through multiple influenza seasons.51

Research and production of such a vaccine are expected to require funding of about $1 billion over the next 5 years.

Boosting effectiveness

Estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness range from 40% to 60% in years when the vaccine viruses closely match the circulating viruses, and variably lower when they do not match. The efficacy of most other vaccines given to prevent other infections is much higher.

New technologies to improve influenza vaccine effectiveness are needed, particularly for influenza A(H3N2) viruses, which are rapidly evolving and are highly susceptible to egg-adaptive mutations in the manufacturing process.

In one study, a nanoparticle vaccine formulated with a saponin-based adjuvant induced hemagglutination inhibition responses that were even greater than those induced by the high-dose vaccine.52

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) may be a more effective vaccine target than traditional influenza vaccines that target IgG, since different parts of IgA may engage the influenza virus simultaneously.53

Vaccines can be developed more quickly than in the past. The timeline from viral sequencing to human studies with deoxyribonucleic acid plasmid vaccines decreased from 20 months in 2003 for the severe acquired respiratory syndrome coronavirus to 11 months in 2006 for influenza A/Indonesia/2006 (H5), to 4 months in 2009 for influenza A/California/2009 (H1), to 3.5 months in 2016 for Zika virus.54 This is because it is possible today to sequence a virus and insert the genetic material into a vaccine platform without ever having to grow the virus.

TREATMENT

Numerous studies have found anti-influenza medications to be effective. Nevertheless, in an analysis of the 2011–2016 influenza seasons, only 15% of high-risk patients were prescribed anti-influenza medications within 2 days of symptom onset, including 37% in those with laboratory-confirmed influenza.55 Fever was associated with an increased rate of antiviral treatment, but 25% of high-risk outpatients were afebrile. Empiric treatment of 4 high-risk outpatients with acute respiratory illness was needed to treat 1 patient with influenza.55

Treatment with a neuraminidase inhibitor within 2 days of illness has recently been shown to improve survival and shorten duration of viral shedding in patients with avian influenza A(H7N9) infection.56 Antiviral treatment within 2 days of illness is associated with improved outcomes in transplant recipients57 and with a lower risk of otitis media in children.58

Appropriate anti-influenza treatment is as important as avoiding unnecessary antibiotics. Regrettably, as many as one-third of patients with laboratory-confirmed influenza are prescribed antibiotics.59

The US Food and Drug Administration warns against fraudulent unapproved over-the-counter influenza products.60

Baloxavir marboxil

Baloxavir marboxil is a new anti-influenza medication approved in Japan in February 2018 and anticipated to be available in the United States sometime in 2019.

This prodrug is hydrolyzed in vivo to the active metabolite, which selectively inhibits cap-dependent endonuclease enzyme, a key enzyme in initiation of messenger ribonucleic acid synthesis required for influenza viral replication.61

In a double-blind phase 3 trial, the median time to alleviation of influenza symptoms is 26.5 hours shorter with baloxavir marboxil than with placebo. One tablet was as effective as 5 days of the neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir and was associated with greater reduction in viral load 1 day after initiation, and similar side effects.62 Of concern is the emergence of nucleic acid substitutions conferring resistance to baloxavir; this occurred in 2.2% and 9.7% of baloxavir recipients in the phase 2 and 3 trials, respectively.

CLOSING THE GAPS

Several gaps in the management of influenza persist since the 1918 pandemic.1 These include gaps in epidemiology, prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.

- Global networks wider than current ones are needed to address this global disease and to prioritize coordination efforts.

- Establishing and strengthening clinical capacity is needed in limited resource settings. New technologies are needed to expedite vaccine development and to achieve progress toward a universal vaccine.

- Current diagnostic tests do not distinguish between seasonal and novel influenza A viruses of zoonotic origin, which are expected to cause the next pandemic.

- Current antivirals have been shown to shorten duration of illness in outpatients with uncomplicated influenza, but the benefit in hospitalized patients has been less well established.

- In 2007, resistance of seasonal influenza A(H1N1) to oseltamivir became widespread. In 2009, pandemic influenza A(H1N1), which is highly susceptible to oseltamivir, replaced the seasonal virus and remains the predominantly circulating A(H1N1) strain.

- A small-molecule fragment, N-cyclohexyaltaurine, binds to the conserved hemagglutinin receptor-binding site in a manner that mimics the binding mode of the natural receptor sialic acid. This can serve as a template to guide the development of novel broad-spectrum small-molecule anti-influenza drugs.63

- Biomarkers that can accurately predict development of severe disease in patients with influenza are needed.

- Uyeki TM, Fowler RA, Fischer WA. Gaps in the clinical management of influenza: a century since the 1918 pandemic. JAMA 2018; 320(8):755–756. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.8113

- Garten R, Blanton L, Elal AI, et al. Update: influenza activity in the United States during the 2017–18 season and composition of the 2018–19 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67(22):634–642. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a4

- Tokars JI, Olsen SJ, Reed C. Seasonal incidence of symptomatic influenza in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(10):1511–1518. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1060

- Elbadawi LI, Talley P, Rolfes MA, et al. Non-mumps viral parotitis during the 2014–2015 influenza season in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2018. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy137

- Thielen BK, Friedlander H, Bistodeau S, et al. Detection of influenza C viruses among outpatients and patients hospitalized for severe acute respiratory infection, Minnesota, 2013–2016. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(7):1092–1098. doi:10.1093/cid/cix931

- Chena Y, Trovãob NS, Wang G, et al. Emergence and evolution of novel reassortant influenza A viruses in canines in southern China. MBio 2018; 9(3):e00909–e00918. doi:10.1128/mBio.00909-18

- Maier HE, Lopez R, Sanchez N, et al. Obesity increases the duration of influenza A virus shedding in adults. J Infect Dis 2018. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiy370

- Warren-Gash C, Blackburn R, Whitaker H, McMenamin J, Hayward AC. Laboratory-confirmed respiratory infections as triggers for acute myocardial infarction and stroke: a self-controlled case series analysis of national linked datasets from Scotland. Eur Respir J 2018; 51(3):1701794. doi:10.1183/13993003.01794-2017

- Blackburn R, Zhao H, Pebody R, Hayward A, Warren-Gash C. Laboratory-confirmed respiratory infections as predictors of hospital admission for myocardial infarction and stroke: time-series analysis of English data for 2004–2015. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67(1):8–17. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1144

- Newsweek; Andrew S. What is disease X? Deadly bird flu virus could be next pandemic. www.newsweek.com/disease-x-bird-flu-deaths-pandemic-what-h7n9-979723. Accessed October 3, 2018.

- Miller AC, Singh I, Koehler E, Polgreen PM. A smartphone-driven thermometer application for real-time population- and individual-level influenza surveillance. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67(3):388–397. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy073

- Kormuth KA, Lin K, Prussin AJ 2nd, et al. Influenza virus infectivity is retained in aerosols and droplets independent of relative humidity, J Infect Dis 2018; 218(5):739–747. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiy221

- Hertzberg VS, Weiss H, Elon L, et. al. Behaviors, movements, and transmission of droplet-mediated respiratory diseases during transcontinental airline flights. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115(14):3623–3627. doi:10.1073/pnas.1711611115

- Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, Walter EB, Fry AM, Jernigan DB. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2018–19 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep 2018; 67(3):1–20. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6703a1

- Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Fry AM, Walter EB, Jernigan DB. Update: ACIP recommendations for the use of quadrivalent live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV4)—United States, 2018–19 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67(22):643–645. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a5

- Flannery B, Chung JR, Belongia EA, et al. Interim estimates of 2017–18 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, February 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67(6):180–185. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6706a2

- Demicheli V, Jefferson T, Ferroni E, Rivetti A, Di Pietrantonj C. Vaccines for preventing influenza in healthy adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 2:CD001269. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001269.pub6

- Flannery B, Smith C, Garten RJ, et al. Influence of birth cohort on effectiveness of 2015–2016 influenza vaccine against medically attended illness due to 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus in the United States. J Infect Dis 2018; 218(2):189–196. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix634

- Rondy M, El Omeiri N, Thompson MG, Leveque A, Moren A, Sullivan SG. Effectiveness of influenza vaccines in preventing severe influenza illness among adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of test-negative design case-control studies. J Infect 2017; 75(5):381–394. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2017.09.010

- Stein Y, Mandelboim M, Sefty H, et al; Israeli Influenza Surveillance Network (IISN). Seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza in primary care in Israel, 2016–2017 season: insights into novel age-specific analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(9):1383–1391. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1013

- Sah P, Medlock J, Fitzpatrick MC, Singer BH, Galvani AP. Optimizing the impact of low-efficacy influenza vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115(20):5151–5156. doi:10.1073/pnas.1802479115

- QuickStats: percentage of currently employed adults aged ≥ 18 years who received influenza vaccine in the past 12 months, by employment category—national health interview survey, United States, 2012 and 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67(16):480. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6716a8

- Healthy People.gov. Immunization and infectious diseases. IID-12. Increase the percentage of children and adults who are vaccinated annually against seasonal influenza. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives. Accessed October 3, 2018.

- Greene MT, Fowler KE, Ratz D, Krein SL, Bradley SF, Saint S. Changes in influenza vaccination requirements for health care personnel in US hospitals. JAMA Network Open 2018; 1(2):e180143. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0143

- Opel DJ, Sonne JA, Mello MM. Vaccination without litigation—addressing religious objections to hospital influenza-vaccination mandates. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(9):785–788. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1716147

- Horowitz J. Italy loosens vaccine law just as children return to school. New York Times Sept. 20, 2018. www.nytimes.com/2018/09/20/world/europe/italy-vaccines-five-star-movement.html.

- National Conference of State Legislature. States with religious and philosophical exemptions from school immunization requirements. www.ncsl.org/research/health/school-immunization-exemption-state-laws.aspx. Accessed October 3, 2018.

- Olive JK, Hotez PJ, Damania A, Nolan MS. The state of the antivaccine movement in the United States: a focused examination of nonmedical exemptions in states and counties. PLoS Med 2018; 15(6):e1002578. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002578

- Logan J, Nederhoff D, Koch B, et al. ‘What have you HEARD about the HERD?’ Does education about local influenza vaccination coverage and herd immunity affect willingness to vaccinate? Vaccine 2018; 36(28):4118–4125. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.05.037

- Belongia EA, Skowronski DM, McLean HQ, Chambers C, Sundaram ME, De Serres G. Repeated annual influenza vaccination and vaccine effectiveness: review of evidence. Expert Rev Vaccines 2017; 16(7):1–14. doi:10.1080/14760584.2017.1334554

- Saito N, Komori K, Suzuki M, et al. Negative impact of prior influenza vaccination on current influenza vaccination among people infected and not infected in prior season: a test-negative case-control study in Japan. Vaccine 2017; 35(4):687–693. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.11.024

- Cheng AC, Macartney KK, Waterer GW, Kotsimbos T, Kelly PM, Blyth CC; Influenza Complications Alert Network (FluCAN) Investigators. Repeated vaccination does not appear to impact upon influenza vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization with confirmed influenza. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64(11):1564–1572. doi:10.1093/cid/cix209

- Rondy M, Launay O, Castilla J, et al; InNHOVE/I-MOVE+working group. Repeated seasonal influenza vaccination among elderly in Europe: effects on laboratory confirmed hospitalised influenza. Vaccine 2017; 35(34):4298–4306. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.088

- Young-Xu Y, van Aalst R, Mahmud SM, et al. Relative vaccine effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccines among Veterans Health Administration patients. J Infect Dis 2018; 217(11):1718–1727. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiy088

- Shay DK, Chillarige Y, Kelman J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccines among US Medicare beneficiaries in preventing postinfluenza deaths during 2012–2013 and 2013–2014. J Infect Dis 2017; 215(4):510–517. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw641

- Madaras-Kelly K, Remington R, Hruza H, Xu D. Comparative effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccines in preventing postinfluenza deaths. J Infect Dis 2018; 218(2):336–337. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix645

- Tam YH, Valkenburg SA, Perera RAPM, et al. Immune responses to twice-annual influenza vaccination in older adults in Hong Kong. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(6):904–912. doi:10.1093/cid/cix900

- Ohfuji S, Deguchi M, Tachibana D, et al; Osaka Pregnant Women Influenza Study Group. Protective effect of maternal influenza vaccination on influenza in their infants: a prospective cohort study. J Infect Dis 2018; 217(6):878–886. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix629

- Katz J, Englund JA, Steinhoff MC, et al. Impact of timing of influenza vaccination in pregnancy on transplacental antibody transfer, influenza incidence, and birth outcomes: a randomized trial in rural Nepal. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67(3):334–340. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy090

- Nunes MC, Cutland CL, Madhi SA. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy and protection against pertussis. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(13):1257–1258. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1705208

- Andrew MK, Shinde V, Ye L, et al; Serious Outcomes Surveillance Network of the Public Health Agency of Canada/Canadian Institutes of Health Research Influenza Research Network (PCIRN) and the Toronto Invasive Bacterial Diseases Network (TIBDN). The importance of frailty in the assessment of influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza-related hospitalization in elderly people. J Infect Dis 2017; 216(4):405–414. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix282

- Park JK, Lee YJ, Shin K, et al. Impact of temporary methotrexate discontinuation for 2 weeks on immunogenicity of seasonal influenza vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77(6):898–904. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213222

- Kumar D, Ferreira VH, Blumberg E, et al. A five-year prospective multi-center evaluation of influenza infection in transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2018. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy294

- Natori Y, Shiotsuka M, Slomovic J, et al. A double-blind, randomized trial of high-dose vs standard-dose influenza vaccine in adult solid-organ transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(11):1698–1704. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1082

- Omer SB, Phadke VK, Bednarczyk BA, Chamberlain AT, Brosseau JL, Orenstein WA. Impact of statins on influenza vaccine effectiveness against medically attended acute respiratory illness. J Infect Dis 2016; 213(8):1216–1223. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiv457

- Dunkle LM, Izikson R, Patriarca P, et al. Efficacy of recombinant influenza vaccine in adults 50 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(25):2427–2436. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1608862

- STAT; Branswell H. How the US military might help answer a critical question about the flu vaccine. www.statnews.com/2018/03/02/flu-vaccine-egg-production-data. Accessed October 3, 2018.

- Paules CI, Sullivan SG, Subbarao K, Fauci AS. Chasing seasonal influenza—the need for a universal influenza vaccine. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(1):7–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1714916

- Jin XW, Mossad SB. Avian influenza: an emerging pandemic threat. Cleve Clin J Med 2005; 72:1129-1134. pmid:16392727

- Wei WI, Brunger AT, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Refinement of the influenza virus hemagglutinin by simulated annealing. J Mol Biol 1990; 212(4):737–761. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(90)90234-D

- Erbelding EJ, Post DJ, Stemmy EJ, et al. A universal influenza vaccine: the strategic plan for the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, J Infect Dis 2018; 218(3):347–354. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiy103

- Shinde V, Fries L, Wu Y, et al. Improved titers against influenza drift variants with a nanoparticle vaccine. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(24):2346–2348. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1803554

- Maurer MA, Meyer L, Bianchi M, et al. Glycosylation of human IgA directly inhibits influenza A and other sialic-acid-binding viruses. Cell Rep 2018; 23(1):90–99. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.027

- Graham BS, Mascola JR, Fauci AS. Novel vaccine technologies: essential components of an adequate response to emerging viral diseases. JAMA 2018; 319(14):1431–1432. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0345

- Stewart RJ, Flannery B, Chung JR, et al. Influenza antiviral prescribing for outpatients with an acute respiratory illness and at high risk for influenza-associated complications during 5 influenza seasons—United States, 2011–2016. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(7):1035–1041. doi:10.1093/cid/cix922

- Zheng S, Tang L, Gao H, et al. Benefit of early initiation of neuraminidase inhibitor treatment to hospitalized patients with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(7):1054–1060. doi:10.1093/cid/cix930

- Kumar D, Ferreira VH, Blumberg E, et al. A five-year prospective multi-center evaluation of influenza infection in transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis 2018. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy294

- Malosh RE, Martin ET, Heikkinen T, Brooks WA, Whitley RJ, Monto AS. Efficacy and safety of oseltamivir in children: systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(10):1492–1500. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1040

- Havers FP, Hicks LA, Chung JR, et al. Outpatient antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections during influenza seasons. JAMA Network Open 2018; 1(2):e180243. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0243

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA warns of fraudulent and unapproved flu products. www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm599223.htm. Accessed October 3, 2018.

- Portsmouth S, Kawaguchi K, Arai M, Tsuchiya K, Uehara T. Cap-dependent endonuclease inhibitor S-033188 for the treatment of influenza: results from a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled study in otherwise healthy adolescents and adults with seasonal influenza. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017; 4(suppl 1):S734. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofx180.001

- Hayden FG, Sugaya N, Hirotsu N, et al; Baloxavir Marboxil Investigators Group. Baloxavir Marboxil for uncomplicated influenza in adults and adolescents. N Engl J Med 2018; 379(10):913–923. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1716197

- Kadam RU, Wilson IA. A small-molecule fragment that emulates binding of receptor and broadly neutralizing antibodies to influenza A hemagglutinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018; 115(16):4240–4245. doi:10.1073/pnas.1801999115

This centennial year update focuses primarily on immunization, but also reviews epidemiology, transmission, and treatment.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

2017–2018 was a bad season

The 2017–2018 influenza epidemic was memorable, dominated by influenza A(H3N2) viruses with morbidity and mortality rates approaching pandemic numbers. It lasted 19 weeks, killed more people than any other epidemic since 2010, particularly children, and was associated with 30,453 hospitalizations—almost twice the previous season high in some parts of the United States.2

Regrettably, 171 unvaccinated children died during 2017–2018, accounting for almost 80% of deaths.2 The mean age of the children who died was 7.1 years; 51% had at least 1 underlying medical condition placing them at risk for influenza-related complications, and 57% died after hospitalization.2

Recent estimates of the incidence of symptomatic influenza among all ages ranged from 3% to 11%, which is slightly lower than historical estimates. The rates were higher for children under age 18 than for adults.3 Interestingly, influenza A(H3N2) accounted for 50% of cases of non-mumps viral parotitis during the 2014–2015 influenza season in the United States.4

Influenza C exists but is rare

Influenza A and B account for almost all influenza-related outpatient visits and hospitalizations. Surveillance data from May 2013 through December 2016 showed that influenza C accounts for 0.5% of influenza-related outpatient visits and hospitalizations, particularly affecting children ages 6 to 24 months. Medical comorbidities and copathogens were seen in all patients requiring intensive care and in most hospitalizations.5 Diagnostic tests for influenza C are not widely available.

Dogs and cats: Factories for new flu strains?

While pigs and birds are the major reservoirs of influenza viral genetic diversity from which infection is transmitted to humans, dogs and cats have recently emerged as possible sources of novel reassortant influenza A.6 With their frequent close contact with humans, our pets may prove to pose a significant threat.

Obesity a risk factor for influenza

Obesity emerged as a risk factor for severe influenza in the 2009 pandemic. Recent data also showed that obesity increases the duration of influenza A virus shedding, thus increasing duration of contagiousness.7

Influenza a cardiovascular risk factor

Previous data showed that influenza was a risk factor for cardiovascular events. Two recent epidemiologic studies from the United Kingdom showed that laboratory-confirmed influenza was associated with higher rates of myocardial infarction and stroke for up to 4 weeks.8,9

Which strain is the biggest threat?

Predicting which emerging influenza serotype may cause the next pandemic is difficult, but influenza A(H7N9), which had not infected humans until 2013 but has since infected about 1,600 people in China and killed 37% of them, appears to have the greatest potential.10

National influenza surveillance programs and influenza-related social media applications have been developed and may get a boost from technology. A smartphone equipped with a temperature sensor can instantly detect one’s temperature with great precision. A 2018 study suggested that a smartphone-driven thermometry application correlated well with national influenza-like illness activity and improved its forecast in real time and up to 3 weeks in advance.11

TRANSMISSION

Humidity may not block transmission

Animal studies have suggested that humidity in the air interferes with transmission of airborne influenza virus, partially from biologic inactivation. But when a recent study used humidity-controlled chambers to investigate the stability of the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus in suspended aerosols and stationary droplets, the virus remained infectious in aerosols across a wide range of relative humidities, challenging the common belief that humidity destabilizes respiratory viruses in aerosols.12

One sick passenger may not infect the whole plane

Transmission of respiratory viruses on airplane flights has long been considered a potential avenue for spreading influenza. However, a recent study that monitored movements of individuals on 10 transcontinental US flights and simulated inflight transmission based on these data showed a low probability of direct transmission, except for passengers seated in close proximity to an infectious passenger.13

WHAT’S IN THE NEW FLU SHOT?

The 2018–2019 quadrivalent vaccine for the Northern Hemisphere14 contains the following strains:

- A/Michigan/45/2015 A(H1N1)pdm09-like virus

- A/Singapore/INFIMH-16-0019/2016 (H3N2)-like virus

- B/Colorado/06/2017-like virus (Victoria lineage)

- B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus (Yamagata lineage).

The A(H3N2) (Singapore) and B/Victoria lineage components are new this year. The A(H3N2) strain was the main cause of the 2018 influenza epidemic in the Southern Hemisphere.

The quadrivalent live-attenuated vaccine, which was not recommended during the 2016–2017 and 2017–2018 influenza seasons, has made a comeback and is recommended for the 2018–2019 season in people for whom it is appropriate based on age and comorbidities.15 Although it was effective against influenza B and A(H3N2) viruses, it was less effective against the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09-like viruses during the 2013–2014 and 2015–2016 seasons.

A/Slovenia/2903/2015, the new A(H1N1)pdm09-like virus included in the 2018–2019 quadrivalent live-attenuated vaccine, is significantly more immunogenic than its predecessor, A/Bolivia/559/2013, but its clinical effectiveness remains to be seen.

PROMOTING VACCINATION

How effective is it?

Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the 2017–2018 influenza season was 36% overall, 67% against A(H1N1), 42% against influenza B, and 25% against A(H3N2).16 It is estimated that influenza vaccine prevents 300 to 4,000 deaths annually in the United States alone.17

A 2018 Cochrane review17 concluded that vaccination reduced the incidence of influenza by about half, with 2.3% of the population contracting the flu without vaccination compared with 0.9% with vaccination (risk ratio 0.41, 95% confidence interval 0.36–0.47). The same review found that 71 healthy adults need to be vaccinated to prevent 1 from experiencing influenza, and 29 to prevent 1 influenza-like illness.

Several recent studies showed that influenza vaccine effectiveness varied based on age and influenza serotype, with higher effectiveness in people ages 5 to 17 and ages 18 to 64 than in those age 65 and older.18–20 A mathematical model of influenza transmission and vaccination in the United States determined that even relatively low-efficacy influenza vaccines can be very useful if optimally distributed across age groups.21

Vaccination rates are low, and ‘antivaxxers’ are on the rise

Although the influenza vaccine is recommended in the United States for all people age 6 months and older regardless of the state of their health, vaccination rates remain low. In 2016, only 37% of employed adults were vaccinated. The highest rate was for government employees (45%), followed by private employees (36%), followed by the self-employed (30%).22

A national goal is to immunize 80% of all Americans and 90% of at-risk populations (which include children and the elderly).23 The number of US hospitals that require their employees to be vaccinated increased from 37.1% in 2013 to 61.4% in 2017.24 Regrettably, as of March 2018, 14 lawsuits addressing religious objections to hospital influenza vaccination mandates have been filed.25

Despite hundreds of studies demonstrating the efficacy, safety, and cost savings of influenza vaccination, the antivaccine movement has been growing in the United States and worldwide.26 All US states except West Virginia, Mississippi, and California allow nonmedical exemptions from vaccination based on religious or personal belief.27 Several US metropolitan areas represent “hot spots” for these exemptions.28 This may render such areas vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases, including influenza.

Herd immunity: We’re all in this together

Some argue that the potential adverse effects and the cost of vaccination outweigh the benefits, but the protective benefits of herd immunity are significant for those with comorbidities or compromised immunity.

Educating the public about herd immunity and local influenza vaccination uptake increases people’s willingness to be vaccinated.29 A key educational point is that at least 70% of a community needs to be vaccinated to prevent community outbreaks; this protects everyone, including those who do not mount a protective antibody response to influenza vaccination and those who are not vaccinated.

DOES ANNUAL VACCINATION BLUNT ITS EFFECTIVENESS?

Some studies from the 1970s and 1980s raised concern over a possible negative effect of annual influenza vaccination on vaccine effectiveness. The “antigenic distance hypothesis” holds that vaccine effectiveness is influenced by antigenic similarity between the previous season’s vaccine serotypes and the epidemic serotypes, as well as the antigenic similarity between the serotypes of the current and previous seasons.

A meta-analysis of studies from 2010 through 2015 showed significant inconsistencies in repeat vaccination effects within and between seasons and serotypes. It also showed that vaccine effectiveness may be influenced by more than 1 previous season, particularly for influenza A(H3N2), in which repeated vaccination can blunt the hemagglutinin antibody response.30

A study from Japan showed that people who needed medical attention for influenza in the previous season were at lower risk of a similar event in the current season.31 Prior-season influenza vaccination reduced current-season vaccine effectiveness only in those who did not have medically attended influenza in the prior season. This suggests that infection is more immunogenic than vaccination, but only against the serotype causing the infection and not the other serotypes included in the vaccine.

An Australian study showed that annual influenza vaccination did not decrease vaccine effectiveness against influenza-associated hospitalization. Rather, effectiveness increased by about 15% in those vaccinated in both current and previous seasons compared with those vaccinated in either season alone.32

European investigators showed that repeated seasonal influenza vaccination in the elderly prevented the need for hospitalization due to influenza A(H3N2) and B, but not A(H1N1)pdm09.33

VACCINATION IN SPECIAL POPULATIONS

High-dose vaccine for older adults

The high-dose influenza vaccine has been licensed since 2009 for use in the United States for people ages 65 and older.

Recent studies confirmed that high-dose vaccine is more effective than standard-dose vaccine in veterans34 and US Medicare beneficiaries.35

The high-dose vaccine is rapidly becoming the primary vaccine given to people ages 65 and older in retail pharmacies, where vaccination begins earlier in the season than in providers’ offices.36 Some studies have shown that the standard-dose vaccine wanes in effectiveness toward the end of the influenza season (particularly if the season is long) if it is given very early. It remains to be seen whether the same applies to the high-dose influenza vaccine.

Some advocate twice-annual influenza vaccination, particularly for older adults living in tropical and subtropical areas, where influenza seasons are more prolonged. However, a recently published study observed reductions in influenza-specific hemagglutination inhibition and cell-mediated immunity after twice-annual vaccination.37

Vaccination is beneficial during pregnancy

Many studies have shown the value of influenza vaccination during pregnancy for both mothers and their infants.

One recently published study showed that 18% of infants who developed influenza required hospitalization.38 In that study, prenatal and postpartum maternal influenza vaccination decreased the odds of influenza in infants by 61% and 53%, respectively.

Another study showed that vaccine effectiveness did not vary by gestational age at vaccination.39

Some studies have shown that influenza virus infection can increase susceptibility to certain bacterial infections. A post hoc analysis of an influenza vaccination study in pregnant women suggested that the vaccine was also associated with decreased rates of pertussis in these women.40

Factors that make vaccination less effective

Several factors including age-related frailty and iatrogenic and disease-related immunosuppression can affect vaccine effectiveness.

Frailty. A recent study showed that vaccine effectiveness was 77.6% in nonfrail older adults but only 58.7% in frail older adults.41

Immunosuppression. Temporary discontinuation of methotrexate for 2 weeks after influenza vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis improves vaccine immunogenicity without precipitating disease flare.42 Solid-organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients who received influenza vaccine were less likely to develop pneumonia and require intensive care unit admission.43

The high-dose influenza vaccine is more immunogenic than the standard-dose vaccine in solid-organ transplant recipients.44

Statins are widely prescribed and have recently been associated with reduced influenza vaccine effectiveness against medically attended acute respiratory illness, but their benefits in preventing cardiovascular events outweigh this risk.45

FUTURE VACCINE CONSIDERATIONS

Moving away from eggs

During the annual egg-based production process, which takes several months, the influenza vaccine acquires antigenic changes that allow replication in eggs, particularly in the hemagglutinin protein, which mediates receptor binding. This process of egg adaptation may cause antigenic changes that decrease vaccine effectiveness against circulating viruses.

The cell-based baculovirus influenza vaccine grown in dog kidney cells has higher antigenic content and is not subject to the limitations of egg-based vaccine, although it still requires annual updates. A recombinant influenza vaccine reduces the probability of influenza-like illness by 30% compared with the egg-based influenza vaccine, but also still requires annual updates.46 The market share of these non-egg-based vaccines is small, and thus their effectiveness has yet to be demonstrated.

The US Department of Defense administered the cell-based influenza vaccine to about one-third of Armed Forces personnel, their families, and retirees in the 2017–2018 influenza seasons, and data on its effectiveness are expected in the near future.47

A universal vaccine would be ideal

The quest continues for a universal influenza vaccine, one that remains protective for several years and does not require annual updates.48 Such a vaccine would protect against seasonal epidemic influenza drift variants and pandemic strains. More people could likely be persuaded to be vaccinated once rather than every year.

An ideal universal vaccine would be suitable for all age groups, at least 75% effective against symptomatic influenza virus infection, protective against all influenza A viruses (influenza A, not B, causes pandemics and seasonal epidemics), and durable through multiple influenza seasons.51

Research and production of such a vaccine are expected to require funding of about $1 billion over the next 5 years.

Boosting effectiveness

Estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness range from 40% to 60% in years when the vaccine viruses closely match the circulating viruses, and variably lower when they do not match. The efficacy of most other vaccines given to prevent other infections is much higher.

New technologies to improve influenza vaccine effectiveness are needed, particularly for influenza A(H3N2) viruses, which are rapidly evolving and are highly susceptible to egg-adaptive mutations in the manufacturing process.

In one study, a nanoparticle vaccine formulated with a saponin-based adjuvant induced hemagglutination inhibition responses that were even greater than those induced by the high-dose vaccine.52

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) may be a more effective vaccine target than traditional influenza vaccines that target IgG, since different parts of IgA may engage the influenza virus simultaneously.53

Vaccines can be developed more quickly than in the past. The timeline from viral sequencing to human studies with deoxyribonucleic acid plasmid vaccines decreased from 20 months in 2003 for the severe acquired respiratory syndrome coronavirus to 11 months in 2006 for influenza A/Indonesia/2006 (H5), to 4 months in 2009 for influenza A/California/2009 (H1), to 3.5 months in 2016 for Zika virus.54 This is because it is possible today to sequence a virus and insert the genetic material into a vaccine platform without ever having to grow the virus.

TREATMENT

Numerous studies have found anti-influenza medications to be effective. Nevertheless, in an analysis of the 2011–2016 influenza seasons, only 15% of high-risk patients were prescribed anti-influenza medications within 2 days of symptom onset, including 37% in those with laboratory-confirmed influenza.55 Fever was associated with an increased rate of antiviral treatment, but 25% of high-risk outpatients were afebrile. Empiric treatment of 4 high-risk outpatients with acute respiratory illness was needed to treat 1 patient with influenza.55

Treatment with a neuraminidase inhibitor within 2 days of illness has recently been shown to improve survival and shorten duration of viral shedding in patients with avian influenza A(H7N9) infection.56 Antiviral treatment within 2 days of illness is associated with improved outcomes in transplant recipients57 and with a lower risk of otitis media in children.58

Appropriate anti-influenza treatment is as important as avoiding unnecessary antibiotics. Regrettably, as many as one-third of patients with laboratory-confirmed influenza are prescribed antibiotics.59

The US Food and Drug Administration warns against fraudulent unapproved over-the-counter influenza products.60

Baloxavir marboxil

Baloxavir marboxil is a new anti-influenza medication approved in Japan in February 2018 and anticipated to be available in the United States sometime in 2019.

This prodrug is hydrolyzed in vivo to the active metabolite, which selectively inhibits cap-dependent endonuclease enzyme, a key enzyme in initiation of messenger ribonucleic acid synthesis required for influenza viral replication.61

In a double-blind phase 3 trial, the median time to alleviation of influenza symptoms is 26.5 hours shorter with baloxavir marboxil than with placebo. One tablet was as effective as 5 days of the neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir and was associated with greater reduction in viral load 1 day after initiation, and similar side effects.62 Of concern is the emergence of nucleic acid substitutions conferring resistance to baloxavir; this occurred in 2.2% and 9.7% of baloxavir recipients in the phase 2 and 3 trials, respectively.

CLOSING THE GAPS

Several gaps in the management of influenza persist since the 1918 pandemic.1 These include gaps in epidemiology, prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.

- Global networks wider than current ones are needed to address this global disease and to prioritize coordination efforts.

- Establishing and strengthening clinical capacity is needed in limited resource settings. New technologies are needed to expedite vaccine development and to achieve progress toward a universal vaccine.

- Current diagnostic tests do not distinguish between seasonal and novel influenza A viruses of zoonotic origin, which are expected to cause the next pandemic.

- Current antivirals have been shown to shorten duration of illness in outpatients with uncomplicated influenza, but the benefit in hospitalized patients has been less well established.

- In 2007, resistance of seasonal influenza A(H1N1) to oseltamivir became widespread. In 2009, pandemic influenza A(H1N1), which is highly susceptible to oseltamivir, replaced the seasonal virus and remains the predominantly circulating A(H1N1) strain.

- A small-molecule fragment, N-cyclohexyaltaurine, binds to the conserved hemagglutinin receptor-binding site in a manner that mimics the binding mode of the natural receptor sialic acid. This can serve as a template to guide the development of novel broad-spectrum small-molecule anti-influenza drugs.63

- Biomarkers that can accurately predict development of severe disease in patients with influenza are needed.

This centennial year update focuses primarily on immunization, but also reviews epidemiology, transmission, and treatment.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

2017–2018 was a bad season

The 2017–2018 influenza epidemic was memorable, dominated by influenza A(H3N2) viruses with morbidity and mortality rates approaching pandemic numbers. It lasted 19 weeks, killed more people than any other epidemic since 2010, particularly children, and was associated with 30,453 hospitalizations—almost twice the previous season high in some parts of the United States.2

Regrettably, 171 unvaccinated children died during 2017–2018, accounting for almost 80% of deaths.2 The mean age of the children who died was 7.1 years; 51% had at least 1 underlying medical condition placing them at risk for influenza-related complications, and 57% died after hospitalization.2

Recent estimates of the incidence of symptomatic influenza among all ages ranged from 3% to 11%, which is slightly lower than historical estimates. The rates were higher for children under age 18 than for adults.3 Interestingly, influenza A(H3N2) accounted for 50% of cases of non-mumps viral parotitis during the 2014–2015 influenza season in the United States.4

Influenza C exists but is rare

Influenza A and B account for almost all influenza-related outpatient visits and hospitalizations. Surveillance data from May 2013 through December 2016 showed that influenza C accounts for 0.5% of influenza-related outpatient visits and hospitalizations, particularly affecting children ages 6 to 24 months. Medical comorbidities and copathogens were seen in all patients requiring intensive care and in most hospitalizations.5 Diagnostic tests for influenza C are not widely available.

Dogs and cats: Factories for new flu strains?

While pigs and birds are the major reservoirs of influenza viral genetic diversity from which infection is transmitted to humans, dogs and cats have recently emerged as possible sources of novel reassortant influenza A.6 With their frequent close contact with humans, our pets may prove to pose a significant threat.

Obesity a risk factor for influenza

Obesity emerged as a risk factor for severe influenza in the 2009 pandemic. Recent data also showed that obesity increases the duration of influenza A virus shedding, thus increasing duration of contagiousness.7

Influenza a cardiovascular risk factor

Previous data showed that influenza was a risk factor for cardiovascular events. Two recent epidemiologic studies from the United Kingdom showed that laboratory-confirmed influenza was associated with higher rates of myocardial infarction and stroke for up to 4 weeks.8,9

Which strain is the biggest threat?

Predicting which emerging influenza serotype may cause the next pandemic is difficult, but influenza A(H7N9), which had not infected humans until 2013 but has since infected about 1,600 people in China and killed 37% of them, appears to have the greatest potential.10

National influenza surveillance programs and influenza-related social media applications have been developed and may get a boost from technology. A smartphone equipped with a temperature sensor can instantly detect one’s temperature with great precision. A 2018 study suggested that a smartphone-driven thermometry application correlated well with national influenza-like illness activity and improved its forecast in real time and up to 3 weeks in advance.11

TRANSMISSION

Humidity may not block transmission

Animal studies have suggested that humidity in the air interferes with transmission of airborne influenza virus, partially from biologic inactivation. But when a recent study used humidity-controlled chambers to investigate the stability of the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus in suspended aerosols and stationary droplets, the virus remained infectious in aerosols across a wide range of relative humidities, challenging the common belief that humidity destabilizes respiratory viruses in aerosols.12

One sick passenger may not infect the whole plane

Transmission of respiratory viruses on airplane flights has long been considered a potential avenue for spreading influenza. However, a recent study that monitored movements of individuals on 10 transcontinental US flights and simulated inflight transmission based on these data showed a low probability of direct transmission, except for passengers seated in close proximity to an infectious passenger.13

WHAT’S IN THE NEW FLU SHOT?

The 2018–2019 quadrivalent vaccine for the Northern Hemisphere14 contains the following strains:

- A/Michigan/45/2015 A(H1N1)pdm09-like virus

- A/Singapore/INFIMH-16-0019/2016 (H3N2)-like virus

- B/Colorado/06/2017-like virus (Victoria lineage)

- B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus (Yamagata lineage).

The A(H3N2) (Singapore) and B/Victoria lineage components are new this year. The A(H3N2) strain was the main cause of the 2018 influenza epidemic in the Southern Hemisphere.

The quadrivalent live-attenuated vaccine, which was not recommended during the 2016–2017 and 2017–2018 influenza seasons, has made a comeback and is recommended for the 2018–2019 season in people for whom it is appropriate based on age and comorbidities.15 Although it was effective against influenza B and A(H3N2) viruses, it was less effective against the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09-like viruses during the 2013–2014 and 2015–2016 seasons.

A/Slovenia/2903/2015, the new A(H1N1)pdm09-like virus included in the 2018–2019 quadrivalent live-attenuated vaccine, is significantly more immunogenic than its predecessor, A/Bolivia/559/2013, but its clinical effectiveness remains to be seen.

PROMOTING VACCINATION

How effective is it?

Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the 2017–2018 influenza season was 36% overall, 67% against A(H1N1), 42% against influenza B, and 25% against A(H3N2).16 It is estimated that influenza vaccine prevents 300 to 4,000 deaths annually in the United States alone.17

A 2018 Cochrane review17 concluded that vaccination reduced the incidence of influenza by about half, with 2.3% of the population contracting the flu without vaccination compared with 0.9% with vaccination (risk ratio 0.41, 95% confidence interval 0.36–0.47). The same review found that 71 healthy adults need to be vaccinated to prevent 1 from experiencing influenza, and 29 to prevent 1 influenza-like illness.

Several recent studies showed that influenza vaccine effectiveness varied based on age and influenza serotype, with higher effectiveness in people ages 5 to 17 and ages 18 to 64 than in those age 65 and older.18–20 A mathematical model of influenza transmission and vaccination in the United States determined that even relatively low-efficacy influenza vaccines can be very useful if optimally distributed across age groups.21

Vaccination rates are low, and ‘antivaxxers’ are on the rise

Although the influenza vaccine is recommended in the United States for all people age 6 months and older regardless of the state of their health, vaccination rates remain low. In 2016, only 37% of employed adults were vaccinated. The highest rate was for government employees (45%), followed by private employees (36%), followed by the self-employed (30%).22

A national goal is to immunize 80% of all Americans and 90% of at-risk populations (which include children and the elderly).23 The number of US hospitals that require their employees to be vaccinated increased from 37.1% in 2013 to 61.4% in 2017.24 Regrettably, as of March 2018, 14 lawsuits addressing religious objections to hospital influenza vaccination mandates have been filed.25

Despite hundreds of studies demonstrating the efficacy, safety, and cost savings of influenza vaccination, the antivaccine movement has been growing in the United States and worldwide.26 All US states except West Virginia, Mississippi, and California allow nonmedical exemptions from vaccination based on religious or personal belief.27 Several US metropolitan areas represent “hot spots” for these exemptions.28 This may render such areas vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases, including influenza.

Herd immunity: We’re all in this together

Some argue that the potential adverse effects and the cost of vaccination outweigh the benefits, but the protective benefits of herd immunity are significant for those with comorbidities or compromised immunity.

Educating the public about herd immunity and local influenza vaccination uptake increases people’s willingness to be vaccinated.29 A key educational point is that at least 70% of a community needs to be vaccinated to prevent community outbreaks; this protects everyone, including those who do not mount a protective antibody response to influenza vaccination and those who are not vaccinated.

DOES ANNUAL VACCINATION BLUNT ITS EFFECTIVENESS?

Some studies from the 1970s and 1980s raised concern over a possible negative effect of annual influenza vaccination on vaccine effectiveness. The “antigenic distance hypothesis” holds that vaccine effectiveness is influenced by antigenic similarity between the previous season’s vaccine serotypes and the epidemic serotypes, as well as the antigenic similarity between the serotypes of the current and previous seasons.

A meta-analysis of studies from 2010 through 2015 showed significant inconsistencies in repeat vaccination effects within and between seasons and serotypes. It also showed that vaccine effectiveness may be influenced by more than 1 previous season, particularly for influenza A(H3N2), in which repeated vaccination can blunt the hemagglutinin antibody response.30

A study from Japan showed that people who needed medical attention for influenza in the previous season were at lower risk of a similar event in the current season.31 Prior-season influenza vaccination reduced current-season vaccine effectiveness only in those who did not have medically attended influenza in the prior season. This suggests that infection is more immunogenic than vaccination, but only against the serotype causing the infection and not the other serotypes included in the vaccine.

An Australian study showed that annual influenza vaccination did not decrease vaccine effectiveness against influenza-associated hospitalization. Rather, effectiveness increased by about 15% in those vaccinated in both current and previous seasons compared with those vaccinated in either season alone.32

European investigators showed that repeated seasonal influenza vaccination in the elderly prevented the need for hospitalization due to influenza A(H3N2) and B, but not A(H1N1)pdm09.33

VACCINATION IN SPECIAL POPULATIONS

High-dose vaccine for older adults

The high-dose influenza vaccine has been licensed since 2009 for use in the United States for people ages 65 and older.

Recent studies confirmed that high-dose vaccine is more effective than standard-dose vaccine in veterans34 and US Medicare beneficiaries.35

The high-dose vaccine is rapidly becoming the primary vaccine given to people ages 65 and older in retail pharmacies, where vaccination begins earlier in the season than in providers’ offices.36 Some studies have shown that the standard-dose vaccine wanes in effectiveness toward the end of the influenza season (particularly if the season is long) if it is given very early. It remains to be seen whether the same applies to the high-dose influenza vaccine.

Some advocate twice-annual influenza vaccination, particularly for older adults living in tropical and subtropical areas, where influenza seasons are more prolonged. However, a recently published study observed reductions in influenza-specific hemagglutination inhibition and cell-mediated immunity after twice-annual vaccination.37

Vaccination is beneficial during pregnancy

Many studies have shown the value of influenza vaccination during pregnancy for both mothers and their infants.

One recently published study showed that 18% of infants who developed influenza required hospitalization.38 In that study, prenatal and postpartum maternal influenza vaccination decreased the odds of influenza in infants by 61% and 53%, respectively.

Another study showed that vaccine effectiveness did not vary by gestational age at vaccination.39

Some studies have shown that influenza virus infection can increase susceptibility to certain bacterial infections. A post hoc analysis of an influenza vaccination study in pregnant women suggested that the vaccine was also associated with decreased rates of pertussis in these women.40

Factors that make vaccination less effective

Several factors including age-related frailty and iatrogenic and disease-related immunosuppression can affect vaccine effectiveness.

Frailty. A recent study showed that vaccine effectiveness was 77.6% in nonfrail older adults but only 58.7% in frail older adults.41

Immunosuppression. Temporary discontinuation of methotrexate for 2 weeks after influenza vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis improves vaccine immunogenicity without precipitating disease flare.42 Solid-organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients who received influenza vaccine were less likely to develop pneumonia and require intensive care unit admission.43

The high-dose influenza vaccine is more immunogenic than the standard-dose vaccine in solid-organ transplant recipients.44

Statins are widely prescribed and have recently been associated with reduced influenza vaccine effectiveness against medically attended acute respiratory illness, but their benefits in preventing cardiovascular events outweigh this risk.45

FUTURE VACCINE CONSIDERATIONS

Moving away from eggs

During the annual egg-based production process, which takes several months, the influenza vaccine acquires antigenic changes that allow replication in eggs, particularly in the hemagglutinin protein, which mediates receptor binding. This process of egg adaptation may cause antigenic changes that decrease vaccine effectiveness against circulating viruses.

The cell-based baculovirus influenza vaccine grown in dog kidney cells has higher antigenic content and is not subject to the limitations of egg-based vaccine, although it still requires annual updates. A recombinant influenza vaccine reduces the probability of influenza-like illness by 30% compared with the egg-based influenza vaccine, but also still requires annual updates.46 The market share of these non-egg-based vaccines is small, and thus their effectiveness has yet to be demonstrated.

The US Department of Defense administered the cell-based influenza vaccine to about one-third of Armed Forces personnel, their families, and retirees in the 2017–2018 influenza seasons, and data on its effectiveness are expected in the near future.47

A universal vaccine would be ideal

The quest continues for a universal influenza vaccine, one that remains protective for several years and does not require annual updates.48 Such a vaccine would protect against seasonal epidemic influenza drift variants and pandemic strains. More people could likely be persuaded to be vaccinated once rather than every year.

An ideal universal vaccine would be suitable for all age groups, at least 75% effective against symptomatic influenza virus infection, protective against all influenza A viruses (influenza A, not B, causes pandemics and seasonal epidemics), and durable through multiple influenza seasons.51

Research and production of such a vaccine are expected to require funding of about $1 billion over the next 5 years.

Boosting effectiveness

Estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness range from 40% to 60% in years when the vaccine viruses closely match the circulating viruses, and variably lower when they do not match. The efficacy of most other vaccines given to prevent other infections is much higher.

New technologies to improve influenza vaccine effectiveness are needed, particularly for influenza A(H3N2) viruses, which are rapidly evolving and are highly susceptible to egg-adaptive mutations in the manufacturing process.

In one study, a nanoparticle vaccine formulated with a saponin-based adjuvant induced hemagglutination inhibition responses that were even greater than those induced by the high-dose vaccine.52

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) may be a more effective vaccine target than traditional influenza vaccines that target IgG, since different parts of IgA may engage the influenza virus simultaneously.53

Vaccines can be developed more quickly than in the past. The timeline from viral sequencing to human studies with deoxyribonucleic acid plasmid vaccines decreased from 20 months in 2003 for the severe acquired respiratory syndrome coronavirus to 11 months in 2006 for influenza A/Indonesia/2006 (H5), to 4 months in 2009 for influenza A/California/2009 (H1), to 3.5 months in 2016 for Zika virus.54 This is because it is possible today to sequence a virus and insert the genetic material into a vaccine platform without ever having to grow the virus.

TREATMENT

Numerous studies have found anti-influenza medications to be effective. Nevertheless, in an analysis of the 2011–2016 influenza seasons, only 15% of high-risk patients were prescribed anti-influenza medications within 2 days of symptom onset, including 37% in those with laboratory-confirmed influenza.55 Fever was associated with an increased rate of antiviral treatment, but 25% of high-risk outpatients were afebrile. Empiric treatment of 4 high-risk outpatients with acute respiratory illness was needed to treat 1 patient with influenza.55

Treatment with a neuraminidase inhibitor within 2 days of illness has recently been shown to improve survival and shorten duration of viral shedding in patients with avian influenza A(H7N9) infection.56 Antiviral treatment within 2 days of illness is associated with improved outcomes in transplant recipients57 and with a lower risk of otitis media in children.58

Appropriate anti-influenza treatment is as important as avoiding unnecessary antibiotics. Regrettably, as many as one-third of patients with laboratory-confirmed influenza are prescribed antibiotics.59

The US Food and Drug Administration warns against fraudulent unapproved over-the-counter influenza products.60

Baloxavir marboxil

Baloxavir marboxil is a new anti-influenza medication approved in Japan in February 2018 and anticipated to be available in the United States sometime in 2019.

This prodrug is hydrolyzed in vivo to the active metabolite, which selectively inhibits cap-dependent endonuclease enzyme, a key enzyme in initiation of messenger ribonucleic acid synthesis required for influenza viral replication.61

In a double-blind phase 3 trial, the median time to alleviation of influenza symptoms is 26.5 hours shorter with baloxavir marboxil than with placebo. One tablet was as effective as 5 days of the neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir and was associated with greater reduction in viral load 1 day after initiation, and similar side effects.62 Of concern is the emergence of nucleic acid substitutions conferring resistance to baloxavir; this occurred in 2.2% and 9.7% of baloxavir recipients in the phase 2 and 3 trials, respectively.

CLOSING THE GAPS

Several gaps in the management of influenza persist since the 1918 pandemic.1 These include gaps in epidemiology, prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.

- Global networks wider than current ones are needed to address this global disease and to prioritize coordination efforts.

- Establishing and strengthening clinical capacity is needed in limited resource settings. New technologies are needed to expedite vaccine development and to achieve progress toward a universal vaccine.

- Current diagnostic tests do not distinguish between seasonal and novel influenza A viruses of zoonotic origin, which are expected to cause the next pandemic.

- Current antivirals have been shown to shorten duration of illness in outpatients with uncomplicated influenza, but the benefit in hospitalized patients has been less well established.

- In 2007, resistance of seasonal influenza A(H1N1) to oseltamivir became widespread. In 2009, pandemic influenza A(H1N1), which is highly susceptible to oseltamivir, replaced the seasonal virus and remains the predominantly circulating A(H1N1) strain.

- A small-molecule fragment, N-cyclohexyaltaurine, binds to the conserved hemagglutinin receptor-binding site in a manner that mimics the binding mode of the natural receptor sialic acid. This can serve as a template to guide the development of novel broad-spectrum small-molecule anti-influenza drugs.63

- Biomarkers that can accurately predict development of severe disease in patients with influenza are needed.

- Uyeki TM, Fowler RA, Fischer WA. Gaps in the clinical management of influenza: a century since the 1918 pandemic. JAMA 2018; 320(8):755–756. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.8113

- Garten R, Blanton L, Elal AI, et al. Update: influenza activity in the United States during the 2017–18 season and composition of the 2018–19 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67(22):634–642. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a4

- Tokars JI, Olsen SJ, Reed C. Seasonal incidence of symptomatic influenza in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(10):1511–1518. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1060

- Elbadawi LI, Talley P, Rolfes MA, et al. Non-mumps viral parotitis during the 2014–2015 influenza season in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2018. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy137

- Thielen BK, Friedlander H, Bistodeau S, et al. Detection of influenza C viruses among outpatients and patients hospitalized for severe acute respiratory infection, Minnesota, 2013–2016. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(7):1092–1098. doi:10.1093/cid/cix931

- Chena Y, Trovãob NS, Wang G, et al. Emergence and evolution of novel reassortant influenza A viruses in canines in southern China. MBio 2018; 9(3):e00909–e00918. doi:10.1128/mBio.00909-18