User login

Transition out of the hospital is a vulnerable time for older adults. Medications, particularly opioids, are a common cause of adverse events during this transitionary period.1,2 For hospitalized patients with acute noncancer pain that necessitates opioid treatment, guidelines recommend using short-acting, rather than long-acting, opioids.3,4 Long-acting opioids have a longer duration of action but also have a significantly elevated risk of unintentional overdose and morbidity compared to short-acting opioids, even when total daily dosing is identical.5,6 This risk is highest in the first 2 weeks following initial prescription.7,8

Despite the recent decrease in overall prescription of opioids,9 a small but significant proportion continue to be prescribed as long-acting formulations.10-12 We sought to understand the incidence of, and patient characteristics associated with, long-acting opioid initiation following hospital discharge among opioid-naïve older adults.

METHODS

We examined the 20% random sample of US Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years old who were hospitalized in 2016 and continuously enrolled in Parts A, B, and D for 1 year prior and 1 month following discharge, excluding beneficiaries with cancer or hospice care, those transferred from or discharged to a care facility, and those who had filled a prescription for an opioid within 90 days prior to hospitalization. We identified beneficiaries with a Part D claim for an opioid, excluding methadone and buprenorphine, within 7 days of discharge. We compared beneficiaries with at least one claim for a long-acting opioid (including extended-release formulations) within 7 days of hospital discharge to those with short-acting opioid claims only.

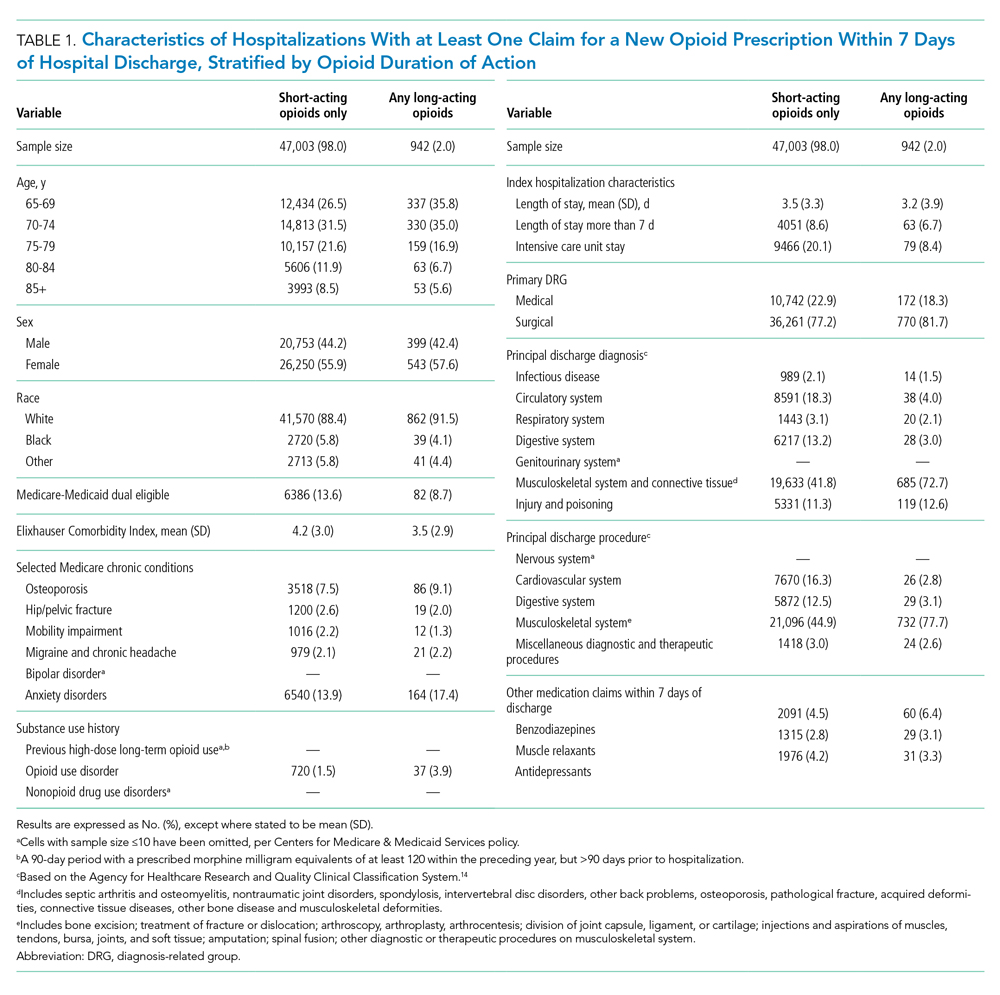

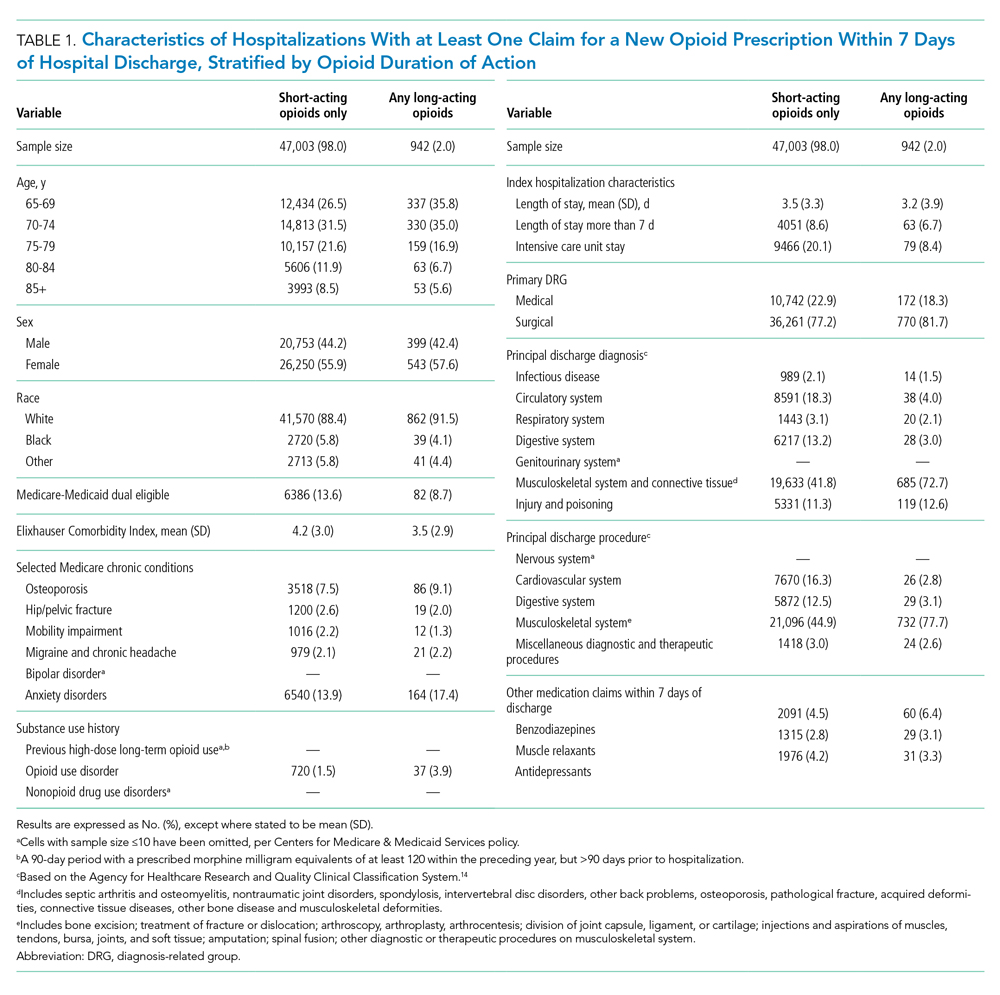

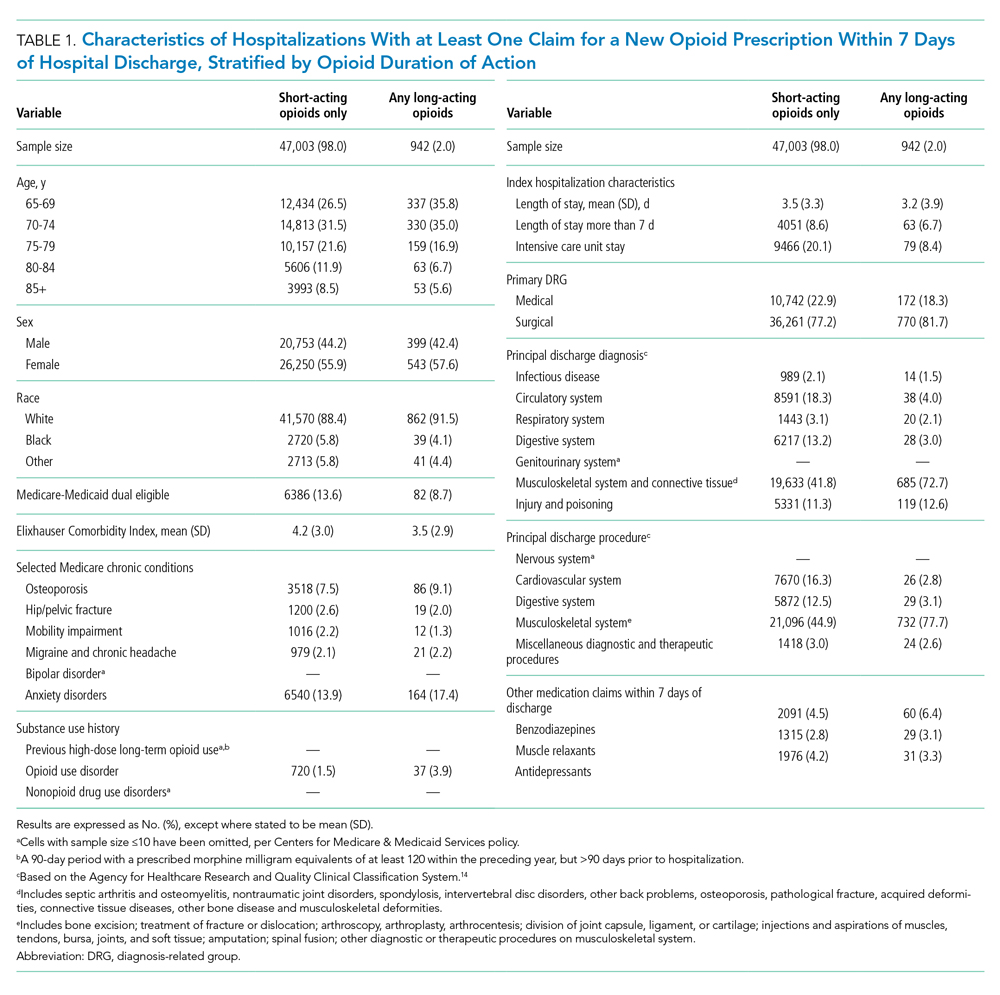

We used a multivariable, generalized estimating equation to determine patient-level factors independently associated with prescription of any long-acting opioids. We selected characteristics that we hypothesized to be associated with new opioid prescription, based on clinical experience and previous literature, including sociodemographics, patient clinical characteristics such as a modified Elixhauser index (a composite index of nearly 30 comorbidities, excluding cancer),13 substance use-related factors, co-prescribed medications, and hospitalization-related factors. The latter included being hospitalized for a medical vs surgical reason, defined based on diagnosis-related group (DRG), primary diagnosis, and primary procedure, grouped using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classification System14 (Table 1).

We conducted a sensitivity analysis, excluding beneficiaries with high-dose long-term opioid use in the year before hospitalization.

RESULTS

Of 258,193 hospitalizations meeting eligibility criteria, 47,945 (18.6%) had an opioid claim within 7 days of discharge and comprised our analytic cohort (see the Appendix Figure for the study consort diagram), including 47,003 (18.2%) with short-acting opioids only and 942 (0.4%) with at least one claim for long-acting opioids, of whom 817 received both short- and long-acting opioids (Table 1).

Beneficiaries with long-acting opioid claims were more likely to be younger (ages 65-69 and 70-74 years) and White than those with claims for short-acting opioids only. They had a lower mean number of Elixhauser comorbidities but a higher prevalence of mental health conditions, including anxiety disorders and opioid use disorder, as well as a higher prevalence of previous high-dose long-term opioid use (occurring more than 90 days prior to hospitalization). They were more likely to have been hospitalized for a procedural rather than a medical reason, with 770 of the 942 (81.7%) beneficiaries receiving long-acting opioids having been hospitalized for a procedural reason (based on DRG). They were also more likely to have benzodiazepine co-prescription.

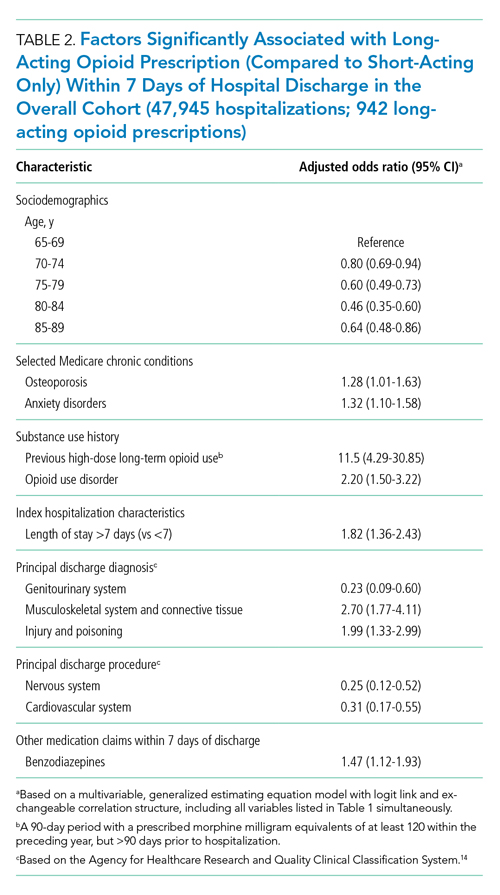

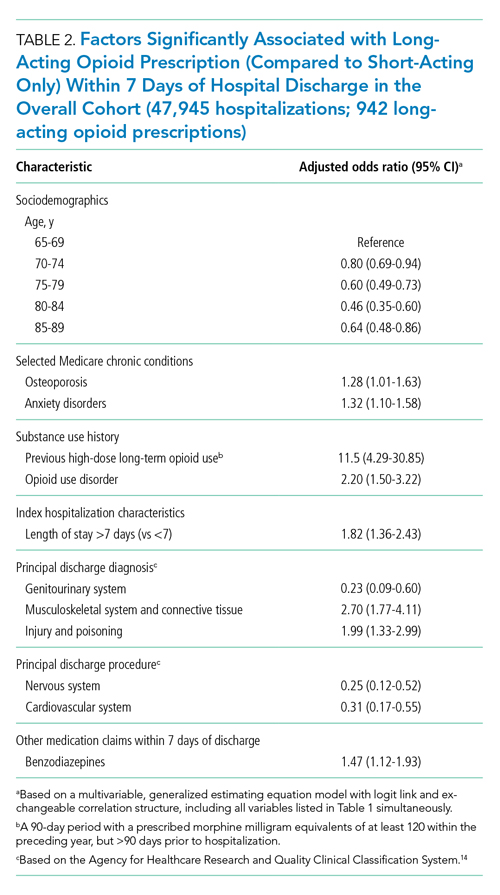

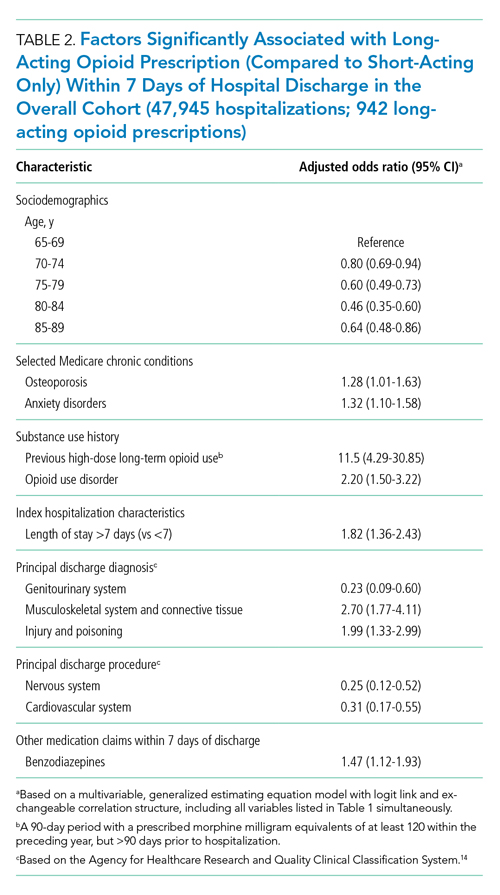

Factors independently associated with receipt of long-acting opioids compared to short-acting opioids only included younger age, having been admitted for a musculoskeletal problem, and presence of known risk factors for opioid-related adverse events, including anxiety disorders, opioid use disorder, prior long-term high-dose opioid use, and benzodiazepine co-prescription (Table 2). After excluding 33 beneficiaries with previous high-dose long-term opioid use in the year before hospitalization, associations were unchanged (Appendix Table).

DISCUSSION

Among a nationally representative sample of opioid-naïve Medicare beneficiaries without cancer, almost 20% filled a new opioid prescription within 7 days of hospital discharge. While prescription of long-acting opioids was uncommon, 81.7% who were prescribed a long-acting opioid had a procedural reason for hospitalization, raising concern since postoperative pain is typically acute and limited. Beneficiaries started on long-acting opioids more frequently had risk factors for opioid-related adverse events, including history of opioid use disorder and benzodiazepine co-prescription. With nearly three-quarters of patients with a long-acting opioid claim having been hospitalized for musculoskeletal disorders or orthopedic procedures, this population represents a key target for quality improvement interventions.

This is the first analysis describing the incidence and factors associated with long-acting opioid receipt shortly after hospital discharge among Medicare beneficiaries. Given that our data predate the publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s consensus statement on safe opioid prescribing in hospitalized patients,3 it is possible that there have been changes to prescribing patterns since 2016 that we are unable to characterize with our data. We are also limited by an inability to determine the appropriateness of any individual long-acting opioid prescription, though previous research has shown that long-acting opioids are frequently inappropriately initiated in older adults.15 Finally, our findings may not be generalizable to non-Medicare populations.

While long-acting opioid initiation following hospitalization is uncommon, these medications are most often prescribed to individuals with pain that is typically of limited duration and those at high risk for harm. Our findings highlight potential targets for systems-based solutions to improve guideline-concordant prescribing of long-acting opioids.

1. Tsilimingras D, Schnipper J, Duke A, et al. Post-discharge adverse events among urban and rural patients of an urban community hospital: a prospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1164-1171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3260-3

2. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007

3. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):263-271. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2980

4. Herzig SJ, Calcaterra SL, Mosher HJ, et al. Safe opioid prescribing for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a systematic review of existing guidelines. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):256-262. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2979

5. Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Thygeson NM, et al. A health plan’s formulary led to reduced use of extended-release opioids but did not lower overall opioid use. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(9):1509-1516. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0391

6. Carey CM, Jena AB, Barnett ML. Patterns of potential opioid misuse and subsequent adverse outcomes in Medicare, 2008 to 2012. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(12):837-845. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-3065

7. Miller M, Barber CW, Leatherman S, et al. Prescription opioid duration of action and the risk of unintentional overdose among patients receiving opioid therapy. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):608-615. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8071

8. Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2415-2423. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.7789

9. Zhu W, Chernew ME, Sherry TB, Maestas N. Initial opioid prescriptions among U.S. commercially insured patients, 2012-2017. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(11):1043-1052. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1807069

10. Starner I, Gleason P. Short-acting, long-acting, and abuse-deterrent opioid utilization patterns among 15 million commercially insured members. Presented at: Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) Nexus; October 3-6, 2016; National Harbor, MD.

11. Young JC, Lund JL, Dasgupta N, Jonsson Funk M. Opioid tolerance and clinically recognized opioid poisoning among patients prescribed extended-release long-acting opioids. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(1):39-47. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.4572

12. Hwang CS, Kang EM, Ding Y, et al. Patterns of immediate-release and extended-release opioid analgesic use in the management of chronic pain, 2003-2014. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180216. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0216

13. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004

14. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-10-CM/PCS. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). October 2018. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs10/ccs10.jsp

15. Willy ME, Graham DJ, Racoosin JA, et al. Candidate metrics for evaluating the impact of prescriber education on the safe use of extended-release/long-acting (ER/LA) opioid analgesics. Pain Med. 2014;15(9):1558-1568. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12459

Transition out of the hospital is a vulnerable time for older adults. Medications, particularly opioids, are a common cause of adverse events during this transitionary period.1,2 For hospitalized patients with acute noncancer pain that necessitates opioid treatment, guidelines recommend using short-acting, rather than long-acting, opioids.3,4 Long-acting opioids have a longer duration of action but also have a significantly elevated risk of unintentional overdose and morbidity compared to short-acting opioids, even when total daily dosing is identical.5,6 This risk is highest in the first 2 weeks following initial prescription.7,8

Despite the recent decrease in overall prescription of opioids,9 a small but significant proportion continue to be prescribed as long-acting formulations.10-12 We sought to understand the incidence of, and patient characteristics associated with, long-acting opioid initiation following hospital discharge among opioid-naïve older adults.

METHODS

We examined the 20% random sample of US Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years old who were hospitalized in 2016 and continuously enrolled in Parts A, B, and D for 1 year prior and 1 month following discharge, excluding beneficiaries with cancer or hospice care, those transferred from or discharged to a care facility, and those who had filled a prescription for an opioid within 90 days prior to hospitalization. We identified beneficiaries with a Part D claim for an opioid, excluding methadone and buprenorphine, within 7 days of discharge. We compared beneficiaries with at least one claim for a long-acting opioid (including extended-release formulations) within 7 days of hospital discharge to those with short-acting opioid claims only.

We used a multivariable, generalized estimating equation to determine patient-level factors independently associated with prescription of any long-acting opioids. We selected characteristics that we hypothesized to be associated with new opioid prescription, based on clinical experience and previous literature, including sociodemographics, patient clinical characteristics such as a modified Elixhauser index (a composite index of nearly 30 comorbidities, excluding cancer),13 substance use-related factors, co-prescribed medications, and hospitalization-related factors. The latter included being hospitalized for a medical vs surgical reason, defined based on diagnosis-related group (DRG), primary diagnosis, and primary procedure, grouped using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classification System14 (Table 1).

We conducted a sensitivity analysis, excluding beneficiaries with high-dose long-term opioid use in the year before hospitalization.

RESULTS

Of 258,193 hospitalizations meeting eligibility criteria, 47,945 (18.6%) had an opioid claim within 7 days of discharge and comprised our analytic cohort (see the Appendix Figure for the study consort diagram), including 47,003 (18.2%) with short-acting opioids only and 942 (0.4%) with at least one claim for long-acting opioids, of whom 817 received both short- and long-acting opioids (Table 1).

Beneficiaries with long-acting opioid claims were more likely to be younger (ages 65-69 and 70-74 years) and White than those with claims for short-acting opioids only. They had a lower mean number of Elixhauser comorbidities but a higher prevalence of mental health conditions, including anxiety disorders and opioid use disorder, as well as a higher prevalence of previous high-dose long-term opioid use (occurring more than 90 days prior to hospitalization). They were more likely to have been hospitalized for a procedural rather than a medical reason, with 770 of the 942 (81.7%) beneficiaries receiving long-acting opioids having been hospitalized for a procedural reason (based on DRG). They were also more likely to have benzodiazepine co-prescription.

Factors independently associated with receipt of long-acting opioids compared to short-acting opioids only included younger age, having been admitted for a musculoskeletal problem, and presence of known risk factors for opioid-related adverse events, including anxiety disorders, opioid use disorder, prior long-term high-dose opioid use, and benzodiazepine co-prescription (Table 2). After excluding 33 beneficiaries with previous high-dose long-term opioid use in the year before hospitalization, associations were unchanged (Appendix Table).

DISCUSSION

Among a nationally representative sample of opioid-naïve Medicare beneficiaries without cancer, almost 20% filled a new opioid prescription within 7 days of hospital discharge. While prescription of long-acting opioids was uncommon, 81.7% who were prescribed a long-acting opioid had a procedural reason for hospitalization, raising concern since postoperative pain is typically acute and limited. Beneficiaries started on long-acting opioids more frequently had risk factors for opioid-related adverse events, including history of opioid use disorder and benzodiazepine co-prescription. With nearly three-quarters of patients with a long-acting opioid claim having been hospitalized for musculoskeletal disorders or orthopedic procedures, this population represents a key target for quality improvement interventions.

This is the first analysis describing the incidence and factors associated with long-acting opioid receipt shortly after hospital discharge among Medicare beneficiaries. Given that our data predate the publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s consensus statement on safe opioid prescribing in hospitalized patients,3 it is possible that there have been changes to prescribing patterns since 2016 that we are unable to characterize with our data. We are also limited by an inability to determine the appropriateness of any individual long-acting opioid prescription, though previous research has shown that long-acting opioids are frequently inappropriately initiated in older adults.15 Finally, our findings may not be generalizable to non-Medicare populations.

While long-acting opioid initiation following hospitalization is uncommon, these medications are most often prescribed to individuals with pain that is typically of limited duration and those at high risk for harm. Our findings highlight potential targets for systems-based solutions to improve guideline-concordant prescribing of long-acting opioids.

Transition out of the hospital is a vulnerable time for older adults. Medications, particularly opioids, are a common cause of adverse events during this transitionary period.1,2 For hospitalized patients with acute noncancer pain that necessitates opioid treatment, guidelines recommend using short-acting, rather than long-acting, opioids.3,4 Long-acting opioids have a longer duration of action but also have a significantly elevated risk of unintentional overdose and morbidity compared to short-acting opioids, even when total daily dosing is identical.5,6 This risk is highest in the first 2 weeks following initial prescription.7,8

Despite the recent decrease in overall prescription of opioids,9 a small but significant proportion continue to be prescribed as long-acting formulations.10-12 We sought to understand the incidence of, and patient characteristics associated with, long-acting opioid initiation following hospital discharge among opioid-naïve older adults.

METHODS

We examined the 20% random sample of US Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years old who were hospitalized in 2016 and continuously enrolled in Parts A, B, and D for 1 year prior and 1 month following discharge, excluding beneficiaries with cancer or hospice care, those transferred from or discharged to a care facility, and those who had filled a prescription for an opioid within 90 days prior to hospitalization. We identified beneficiaries with a Part D claim for an opioid, excluding methadone and buprenorphine, within 7 days of discharge. We compared beneficiaries with at least one claim for a long-acting opioid (including extended-release formulations) within 7 days of hospital discharge to those with short-acting opioid claims only.

We used a multivariable, generalized estimating equation to determine patient-level factors independently associated with prescription of any long-acting opioids. We selected characteristics that we hypothesized to be associated with new opioid prescription, based on clinical experience and previous literature, including sociodemographics, patient clinical characteristics such as a modified Elixhauser index (a composite index of nearly 30 comorbidities, excluding cancer),13 substance use-related factors, co-prescribed medications, and hospitalization-related factors. The latter included being hospitalized for a medical vs surgical reason, defined based on diagnosis-related group (DRG), primary diagnosis, and primary procedure, grouped using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classification System14 (Table 1).

We conducted a sensitivity analysis, excluding beneficiaries with high-dose long-term opioid use in the year before hospitalization.

RESULTS

Of 258,193 hospitalizations meeting eligibility criteria, 47,945 (18.6%) had an opioid claim within 7 days of discharge and comprised our analytic cohort (see the Appendix Figure for the study consort diagram), including 47,003 (18.2%) with short-acting opioids only and 942 (0.4%) with at least one claim for long-acting opioids, of whom 817 received both short- and long-acting opioids (Table 1).

Beneficiaries with long-acting opioid claims were more likely to be younger (ages 65-69 and 70-74 years) and White than those with claims for short-acting opioids only. They had a lower mean number of Elixhauser comorbidities but a higher prevalence of mental health conditions, including anxiety disorders and opioid use disorder, as well as a higher prevalence of previous high-dose long-term opioid use (occurring more than 90 days prior to hospitalization). They were more likely to have been hospitalized for a procedural rather than a medical reason, with 770 of the 942 (81.7%) beneficiaries receiving long-acting opioids having been hospitalized for a procedural reason (based on DRG). They were also more likely to have benzodiazepine co-prescription.

Factors independently associated with receipt of long-acting opioids compared to short-acting opioids only included younger age, having been admitted for a musculoskeletal problem, and presence of known risk factors for opioid-related adverse events, including anxiety disorders, opioid use disorder, prior long-term high-dose opioid use, and benzodiazepine co-prescription (Table 2). After excluding 33 beneficiaries with previous high-dose long-term opioid use in the year before hospitalization, associations were unchanged (Appendix Table).

DISCUSSION

Among a nationally representative sample of opioid-naïve Medicare beneficiaries without cancer, almost 20% filled a new opioid prescription within 7 days of hospital discharge. While prescription of long-acting opioids was uncommon, 81.7% who were prescribed a long-acting opioid had a procedural reason for hospitalization, raising concern since postoperative pain is typically acute and limited. Beneficiaries started on long-acting opioids more frequently had risk factors for opioid-related adverse events, including history of opioid use disorder and benzodiazepine co-prescription. With nearly three-quarters of patients with a long-acting opioid claim having been hospitalized for musculoskeletal disorders or orthopedic procedures, this population represents a key target for quality improvement interventions.

This is the first analysis describing the incidence and factors associated with long-acting opioid receipt shortly after hospital discharge among Medicare beneficiaries. Given that our data predate the publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s consensus statement on safe opioid prescribing in hospitalized patients,3 it is possible that there have been changes to prescribing patterns since 2016 that we are unable to characterize with our data. We are also limited by an inability to determine the appropriateness of any individual long-acting opioid prescription, though previous research has shown that long-acting opioids are frequently inappropriately initiated in older adults.15 Finally, our findings may not be generalizable to non-Medicare populations.

While long-acting opioid initiation following hospitalization is uncommon, these medications are most often prescribed to individuals with pain that is typically of limited duration and those at high risk for harm. Our findings highlight potential targets for systems-based solutions to improve guideline-concordant prescribing of long-acting opioids.

1. Tsilimingras D, Schnipper J, Duke A, et al. Post-discharge adverse events among urban and rural patients of an urban community hospital: a prospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1164-1171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3260-3

2. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007

3. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):263-271. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2980

4. Herzig SJ, Calcaterra SL, Mosher HJ, et al. Safe opioid prescribing for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a systematic review of existing guidelines. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):256-262. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2979

5. Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Thygeson NM, et al. A health plan’s formulary led to reduced use of extended-release opioids but did not lower overall opioid use. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(9):1509-1516. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0391

6. Carey CM, Jena AB, Barnett ML. Patterns of potential opioid misuse and subsequent adverse outcomes in Medicare, 2008 to 2012. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(12):837-845. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-3065

7. Miller M, Barber CW, Leatherman S, et al. Prescription opioid duration of action and the risk of unintentional overdose among patients receiving opioid therapy. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):608-615. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8071

8. Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2415-2423. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.7789

9. Zhu W, Chernew ME, Sherry TB, Maestas N. Initial opioid prescriptions among U.S. commercially insured patients, 2012-2017. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(11):1043-1052. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1807069

10. Starner I, Gleason P. Short-acting, long-acting, and abuse-deterrent opioid utilization patterns among 15 million commercially insured members. Presented at: Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) Nexus; October 3-6, 2016; National Harbor, MD.

11. Young JC, Lund JL, Dasgupta N, Jonsson Funk M. Opioid tolerance and clinically recognized opioid poisoning among patients prescribed extended-release long-acting opioids. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(1):39-47. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.4572

12. Hwang CS, Kang EM, Ding Y, et al. Patterns of immediate-release and extended-release opioid analgesic use in the management of chronic pain, 2003-2014. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180216. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0216

13. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004

14. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-10-CM/PCS. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). October 2018. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs10/ccs10.jsp

15. Willy ME, Graham DJ, Racoosin JA, et al. Candidate metrics for evaluating the impact of prescriber education on the safe use of extended-release/long-acting (ER/LA) opioid analgesics. Pain Med. 2014;15(9):1558-1568. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12459

1. Tsilimingras D, Schnipper J, Duke A, et al. Post-discharge adverse events among urban and rural patients of an urban community hospital: a prospective cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1164-1171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3260-3

2. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-167. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007

3. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):263-271. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2980

4. Herzig SJ, Calcaterra SL, Mosher HJ, et al. Safe opioid prescribing for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a systematic review of existing guidelines. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):256-262. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2979

5. Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Thygeson NM, et al. A health plan’s formulary led to reduced use of extended-release opioids but did not lower overall opioid use. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(9):1509-1516. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0391

6. Carey CM, Jena AB, Barnett ML. Patterns of potential opioid misuse and subsequent adverse outcomes in Medicare, 2008 to 2012. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(12):837-845. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-3065

7. Miller M, Barber CW, Leatherman S, et al. Prescription opioid duration of action and the risk of unintentional overdose among patients receiving opioid therapy. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):608-615. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8071

8. Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2415-2423. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.7789

9. Zhu W, Chernew ME, Sherry TB, Maestas N. Initial opioid prescriptions among U.S. commercially insured patients, 2012-2017. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(11):1043-1052. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1807069

10. Starner I, Gleason P. Short-acting, long-acting, and abuse-deterrent opioid utilization patterns among 15 million commercially insured members. Presented at: Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) Nexus; October 3-6, 2016; National Harbor, MD.

11. Young JC, Lund JL, Dasgupta N, Jonsson Funk M. Opioid tolerance and clinically recognized opioid poisoning among patients prescribed extended-release long-acting opioids. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(1):39-47. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.4572

12. Hwang CS, Kang EM, Ding Y, et al. Patterns of immediate-release and extended-release opioid analgesic use in the management of chronic pain, 2003-2014. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180216. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0216

13. Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004

14. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-10-CM/PCS. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). October 2018. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs10/ccs10.jsp

15. Willy ME, Graham DJ, Racoosin JA, et al. Candidate metrics for evaluating the impact of prescriber education on the safe use of extended-release/long-acting (ER/LA) opioid analgesics. Pain Med. 2014;15(9):1558-1568. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12459

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine