User login

Differentiating the irritable, oppositional child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) from the child with bipolar disorder (BD) often is difficult. To make matters more complicated, 50% to 70% of patients with BD have comorbid ADHD.1,2 Accordingly, clinicians are often faced with the moody, irritable, disruptive child whose parents want to know if he (she) is “bipolar” to try to deal with oppositional and mood behaviors.

In this article, we present an approach that will help you distinguish these 2 disorders from each other.

Precision medicineThere is a lack of evidence-based methods for diagnosing psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents. DSM-5 provides clinicians with diagnostic checklists that rely on the clinician’s judgment and training in evaluating a patient.3 In The innovator’s prescription: a disruptive solution for health care, Christensen et al4 describe how medicine is moving from “intuitive medicine” to empirical medicine and toward “precision medicine.” Intuitive medicine depends on the clinician’s expertise, training, and exposure to different disorders, which is the traditional clinical model that predominates in child psychiatry. Empirical medicine relies on laboratory results, scans, scales, and other standardized tools.

Precision medicine occurs when a disorder can be precisely diagnosed and its cause understood, and when it can be treated with effective, evidence-based therapies. An example of this movement toward precision is Timothy syndrome (TS), a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by physical malformations, cardiac arrhythmias and structural heart defects, webbing of fingers and toes, and autism spectrum disorder. In the past, a child with TS would have been given a diagnosis of intellectual disability, or a specialist in developmental disorders might recognize the pattern of TS. It is now known that TS is caused by mutations in CACNA1C, the gene encoding the calcium channel Cav1.2α subunit, allowing precise diagnosis by genotyping.5

Although there are several tools that help clinicians assess symptoms of ADHD and BD, including rating scales such the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Rating Scale and Young Mania Rating Scale, none of these scales are diagnostic. Youngstrom et al6,7 have developed an evidence-based strategy to diagnose pediatric BD. This method uses a nomogram that takes into account the base rate of BD in a clinical setting and family history of BD.

We will describe and contrast the epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of pediatric BD from ADHD and use the Youngstrom nomogram to better define these patients. Although still far from precision medicine, the type of approach represents an ongoing effort in mental health care to increase diagnostic accuracy and improve treatment outcomes.

Pediatric bipolar disorder

Prevalence of pediatric BD is 1.8% (95% CI, 1.1% to 3.0%),8 which does not include sub-threshold cases of BD. ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) are 8 to 10 times more prevalent. For the purposes of the nomogram, the “base rate” is the rate at which a disorder occurs in different clinical settings. In general outpatient clinics, BD might occur 6% to 8% of the time, whereas in a county-run child psychiatry inpatient facility the rate is 11%.6 A reasonable rate in an outpatient pediatric setting is 6%.

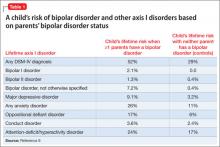

Family history. In the Bipolar Offspring Study,9 the rate of BD in children of parents with BD was 13 times greater than that of controls, and the rate of anxiety and behavior disorders was approximately twice that of children of parents without BD (Table 1).9 This study evaluated 388 children of 233 parents with BD and 251 children of 143 demographically matched controls.

Clinical characteristics. Children and adolescents with BD typically manifest with what can be described as a “mood cycle”—a pronounced shift in mood and energy from one extreme to another. An example would be a child who wakes up with extreme silliness, high energy, and intrusive behavior that persists for several hours, then later becomes sad, depressed, and suicidal with no precipitant for either mood cycle.10 Pediatric patients with BD also exhibit other symptoms of mania during mood cycling periods.

Elevated or expansive mood. The child might have a mood that is inappropriately giddy, silly, elated, or euphoric. Often this mood will be present without reason and last for several hours. It may be distinguished from a transient cheerful mood by the intensity and duration of the episode. The child with BD may have little to no insight about the inappropriate nature of their elevated mood, when present.

Irritable mood. The child might become markedly belligerent or irritated with intense outbursts of anger, 2 to 3 times a day for several hours. An adolescent might appear extremely oppositional, belligerent, or hostile with parents and others.

Grandiosity or inflated self-esteem can be confused with brief childhood fantasies of increased capability. Typically, true grandiosity can manifest as assertion of great competency in all areas of life, which usually cannot be altered by contrary external evidence. Occasionally, this is bizarre and includes delusions of “super powers.” The child in a manic episode will not only assert that she can fly, but will jump off the garage roof to prove it.

Decreased need for sleep. The child may only require 4 to 5 hours of sleep a night during a manic episode without feeling fatigued or showing evidence of tiredness. Consider substance use in this differential diagnosis, especially in adolescents.

Increased talkativeness. Lack of inhibition to social norms may lead pediatric BD patients to blurt out answers during class or repeatedly be disciplined for talking to peers in class. Speech typically is rapid and pressured to the point where it might be continuous and seems to jump between loosely related subjects.

Flight of ideas or racing thoughts. The child or adolescent might report a subjective feeling that his thoughts are moving so rapidly that his speech cannot keep up. Often this is differentiated from rapid speech by the degree of rapidity the patient expresses loosely related topics that might seem completely unrelated to the listener.

Distractibility, short attention span. During a manic episode, the child or adolescent might report that it is impossible to pay attention to class or other outside events because of rapidly changing focus of their thoughts. This symptom must be carefully distinguished from the distractibility and inattention of ADHD, which typically is a more fixed and long-standing pattern rather than a brief episodic phenomenon in a manic or hypomanic episode.

Increase in goal-directed activity. During a mild manic episode, the child or adolescent may be capable of accomplishing a great deal of work. However, episodes that are more severe manifest as an individual starting numerous ambitious projects that she later is unable to complete.

Excessive risk-taking activities. The child or adolescent might become involved in forbidden, pleasurable activities that have a high risk of adverse consequences. This can manifest as hypersexual behavior, frequent fighting, increased recklessness, use of drugs and alcohol, shopping sprees, and reckless driving.

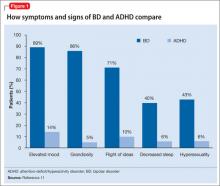

There are few studies comparing patients with comorbid BD and ADHD with patients with only ADHD. Geller et al11 compared 60 children with BD and ADHD (mean age, 10) to age- and sex-matched patients with ADHD and no mood disorder. Compared with children who had ADHD, those with BD exhibited significantly greater elevated mood, grandiosity, flight and/or racing of ideas, decreased need for sleep, and hypersexuality (Figure 1,11). Features common to both groups—and therefore not useful in differentiating the disorders—included irritability, hyperactivity, accelerated speech, and distractibility.

CASE REPORTIrritable and disruptiveBill, age 12, has been brought to see you by his mother because she is concerned about escalating behavior problems at home and school in the past several months. The school principal has called her about his obnoxious behavior with teachers and about other parents’ complaints that he has made unwanted sexual advances to girls who sit next to him in class.

Bill, who is in the 7th grade, is on the verge of being suspended for his inappropriate and disruptive behavior. His parents report that he is irritable around them and stays up all night, messaging his friends on the Internet from his iPad in his bedroom. They attribute his inappropriate sexual behavior to puberty and possibly to the Web sites he views.

Bill’s mother is concerned about his:

• increasing behavior problems during the last several months at home and school

• intensifying irritability and depressive symptoms

• staying up all night on the Internet, phoning friends, and doing projects

• frequent unprovoked, outbursts of rage occurring with increasing frequency and intensity (almost daily)

• moderate grandiosity, including telling the soccer coach and teachers how to do their jobs

• inappropriate sexual behavior, including kissing and touching female classmates.

During your history, you learn that Bill has been a bright and artistic child, with good academic performance. His peer relationships have been satisfactory, but not excellent—he tends to be “bossy” with his peers. He is medically healthy and not taking any medications. As part of your history, you also talk with Bill and his family about exposure to trauma or significant stressors, which they deny. You learn that Bill’s father was diagnosed with BD I at age 32.

Completing the nomogram developed by Youngstrom et al6,7 using these variables (see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for Figure 2)6,7 gives Bill a post-test probability of approximately 42%. The threshold for moving ahead with assessment and possible treatment, the “test-treatment threshold,” depends on your clinical setting.12,13 Our clinical experience is that, when the post-test probability exceeds 30%, further assessment for BD is warranted.

The next strategy is to look at Bill’s scores on externalizing behaviors using an instrument such as the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale. Few pediatric patients with BD will score low on externalizing behaviors.14 Bill scores in the clinically significant range for hyperactivity/impulsivity and positive on the screeners for ODD, conduct disorder (CD), and anxiety/depression.

You decide that Bill is at high risk of pediatric BD; he has a post-test probability of approximately 45%, and many externalizing behaviors on the Vanderbilt. You give Bill a diagnosis of BD I and ADHD and prescribe risperidone, 0.5 mg/d, which results in significant improvement in mood swings and other manic behaviors.

ADHD

Epidemiology. ADHD is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders in childhood, with prevalence estimates of 8% of U.S. children.15,16 Overall, boys are more likely to be assigned a diagnosis of ADHD than girls.15 Although ADHD often is diagnosed in early childhood, research is working to clarify the lifetime prevalence of ADHD into late adolescence and adulthood. Current estimates suggest that ADHD persists into adulthood in close to two-thirds of patients.17 However, the symptom presentation can change during adolescence and adulthood, with less overt hyperactivity and symptoms of impulsivity transitioning to risky behaviors involving trouble with the law, substance use, and sexual promiscuity.17

As in pediatric BD, comorbidity is common in ADHD, with uncomplicated ADHD being the exception rather than the rule. Recent studies have suggested that approximately two-thirds of children who have a diagnosis of ADHD have ≥1 comorbid diagnoses.15 Common comorbidities are similar to those seen in BD, including ODD, CD, anxiety disorders, depression, and learning disability. Several tools and resources are available to help clinicians navigate these issues within their practices.

Family history. Genetics appear to play a large role in ADHD, with twin studies suggesting inheritance of approximately 76%.18 Environmental factors contribute, either in the development of ADHD or in the exacerbation of an underlying familial predisposition. Interestingly, in children with BD, family history often is significant for several family members who have both ADHD and BD. However, in children with ADHD only, family history often reflects an absence of family members with BD.19 Although not diagnostic, this pattern can be helpful when considering a diagnosis of BD vs ADHD.

Clinical picture. ADHD often is recognized in childhood; DSM-5 criteria specify that symptoms be present before age 12 and persist for at least 6 months. This characterization of the timing of symptoms helps exclude behavioral disruptions related to external factors such as trauma (eg, death of a caregiver) or abuse. It also is important to note that symptoms might be present earlier but not come to attention clinically until a later age, perhaps because of increasing demands placed on the child by school, peer groups, and extracurricular activities. To make an ADHD diagnosis, symptoms must be present in >1 setting and interfere with functioning or development.

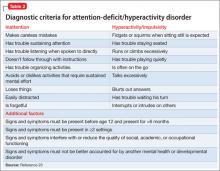

Core symptoms of ADHD include inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that are out of proportion to the child’s developmental level (Table 2).20 When considering diagnosis of ADHD, 6 of 9 symptoms for inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity must be present at a clinically significant level.

Three different ADHD presentations are recognized: combined, inattentive, and hyperactive impulsive. Children with predominant impulsive and hyperactive behaviors generally come to clinical attention at a younger age; inattentive symptoms often take longer to identify.

Children with ADHD have been noted to have lower tolerance for frustration, which might make anger outbursts and aggressive behavior more likely. Anger and aggression in ADHD often stem from impulsivity, rather than irritable mood seen with BD.18 Issues related to self-esteem, depression, substance use, and CD can contribute to symptoms of irritability, anger, and aggression that can occur in children with ADHD. Although these symptoms can overlap with those seen in children with BD, other core symptoms of ADHD will not be present.

ODD is one of the most common comorbidities among children with ADHD, and the combination of ODD and ADHD may be confused with BD. Children with ODD often are noted to exhibit a pattern of negative and defiant behavior that is out of proportion to what is seen in their peers and for their age and developmental level (Table 3).20 When considering an ODD diagnosis, 4 out of 8 symptoms must be present at a clinically significant level.

The following case highlights the potential similarities between ADHD/ODD and BD, with tips on how to distinguish them.

CASE REPORT

Angry and destructiveSam, age 7, has been given a diagnosis of ADHD, but his parents think that he isn’t improving with methylphenidate treatment. They are concerned that he has anger issues like his uncle, who has “bipolar disorder.”

Sam’s parents find that he gets frustrated easily and note that he has frequent short “meltdowns” and “mood swings.” During these episodes he yells, is aggressive towards others, and can be destructive. They are concerned because Sam will become angry quickly, then act as if nothing happened after the meltdown has blown over. Sam’s parents feel that he doesn’t listen to them and often argues when they make a request. His parents note that when they push harder, Sam digs in his heels, which can trigger his meltdowns.

Despite clearly disobeying his parents, Sam often says that things aren’t his fault and blames his parents or siblings instead. Sam seems to disagree with people often. His mother reports “if I say the water looks blue, he’ll say it’s green.” Often, Sam seems to argue or pester others to get a rise out of them. This is causing problems for Sam with his siblings and peers, and significant stress for his parents. Family history suggests that Sam’s uncle may have ADHD with CD or a substance use disorder, rather than true BD. Other than Sam’s uncle, there is no family history for BD.

Sam’s parents say that extended release methylphenidate, 20 mg/d, has helped with hyperactivity, but they are concerned that other symptoms have not improved. Aside from the symptoms listed above, Sam is described as a happy child. There is no history of trauma, and no symptoms of anxiety are noted. Sam sometimes gets “down” when things don’t go his way, but this lasts only for a few hours. Sam has a history of delayed sleep onset, which responded well to melatonin. No other symptoms that suggest mania are described.

You complete the pediatric bipolar nomogram (Figure 3)6,7 and Sam’s parents complete a Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale. At first, Sam seems to have several factors that might indicate BD: aggressive behavior, mood swings, sleep problems, and, possibly, a family history of BD.

However, a careful history provides several clues that Sam has a comorbid diagnosis of ODD. Sam is exhibiting the classic pattern of negativist behavior seen in children with ODD. In contrast to the episodic pattern of BD, these symptoms are prevalent and persistent, and manifest as an overall pattern of functioning. Impulsivity seen in children with ADHD can complicate the picture, but again appears as a consistent pattern rather than bouts of irritability. Sam’s core symptoms of ADHD (hyperactivity) improved with methylphenidate, but the underlying symptoms of ODD persisted.

Sleep problems are common in children who have ADHD and BD, but Sam’s delayed sleep onset responded to melatonin, whereas the insomnia seen in BD often is refractory to lower-intensity interventions, such as melatonin. Taking a careful family history led you to believe that BD in the family is unlikely. Although this type of detail may not always be available, it can be helpful to ask about mental health symptoms that seem to “run in the family.”

Bottom Line

Distinguishing the child who has bipolar disorder from one who has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder can be challenging. A careful history helps ensure that you are on the path toward understanding the diagnostic possibilities. Tools such as the Vanderbilt Rating Scale can further clarify possible diagnoses, and the nomogram approach can provide even more predictive information when considering a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Related Resources

• Children and Adults with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD). www.chadd.org.

• American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Facts for Families. www.aacap.org/cs/root/facts_for_families/ facts_for_families.

• Froehlich TE, Delgado SV, Anixt JS. Expanding medication options for pediatric ADHD. Current Psychiatry. 2013;(12)12:20-29.

• Passarotti AM, Pavuluri MN. Brain functional domains inform therapeutic interventions in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and pediatric bipolar disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(6):897-914.

Drug Brand Names

Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Methylin, Metadate CD, Metadate ER, Methylin ER, Ritalin LA, Ritalin SR, Concerta, Quillivant XR, Daytrana

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Wozniak J, et al. Is comorbidity with ADHD a marker for juvenile-onset mania? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(8):1046-1055.

2. West SA, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adolescent mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(2):271-273.

3. McHugh PR, Slavney PR. Mental illness–comprehensive evaluation or checklist? N Engl J Med. 2012;366(20): 1853-1855.

4. Christensen CM, Grossman JH, Hwang J. The innovator’s prescription: a disruptive solution for health care. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

5. Yazawa M, Hsueh B, Jia X, et al. Using induced pluripotent stem cells to investigate cardiac phenotypes in Timothy syndrome. Nature. 2011;471(7337):230-234.

6. Youngstrom EA, Duax J. Evidence-based assessment of pediatric bipolar disorder, part I: base rate and family history. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(7): 712-717.

7. Youngstrom EA, Jenkins MM, Doss AJ, et al. Evidence-based assessment strategies for pediatric bipolar disorder. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2012;49(1):15-27.

8. Van Meter AR, Moreira AL, Youngstrom EA. Meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(9):1250-1256.

9. Birmaher B, Axelson D, Monk K, et al. Lifetime psychiatric disorders in school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(3):287-296.

10. Youngstrom EA, Birmaher B, Findling RL. Pediatric bipolar disorder: validity, phenomenology, and recommendations for diagnosis. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10 (1 pt 2):194-214.

11. Geller B, Warner K, Williams M, et al. Prepubertal and young adolescent bipolarity versus ADHD: assessment and validity using the WASH-U-KSADS, CBCL and TRF. J Affect Disord. 1998;51(2):93-100.

12. Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Guyatt GH, et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XV. How to use an article about disease probability for differential diagnosis. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1999;281(13):1214-1219.

13. Nease RF Jr, Owens DK, Sox HC Jr. Threshold analysis using diagnostic tests with multiple results. Med Decis Making. 1989;9(2):91-103.

14. Youngstrom EA, Youngstrom JK. Evidence-based assessment of pediatric bipolar disorder, Part II: incorporating information from behavior checklists. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(8):823-828.

15. Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001-2004 NHANES. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):75-81.

16. Larson K, Russ SA, Kahn RS, et al. Patterns of comorbidity, functioning, and service use for US children with ADHD, 2007. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):462-470.

17. Simon V, Czobor P, Bálint S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(3):204-211.

18. Biederman J, Faraone SV. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2005;366(9481):237-248.

19. Sood AB, Razdan A, Weller EB, et al. How to differentiate bipolar disorder from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and other common psychiatric disorders: a guide for clinicians. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2005;7(2): 98-103.

20. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Differentiating the irritable, oppositional child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) from the child with bipolar disorder (BD) often is difficult. To make matters more complicated, 50% to 70% of patients with BD have comorbid ADHD.1,2 Accordingly, clinicians are often faced with the moody, irritable, disruptive child whose parents want to know if he (she) is “bipolar” to try to deal with oppositional and mood behaviors.

In this article, we present an approach that will help you distinguish these 2 disorders from each other.

Precision medicineThere is a lack of evidence-based methods for diagnosing psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents. DSM-5 provides clinicians with diagnostic checklists that rely on the clinician’s judgment and training in evaluating a patient.3 In The innovator’s prescription: a disruptive solution for health care, Christensen et al4 describe how medicine is moving from “intuitive medicine” to empirical medicine and toward “precision medicine.” Intuitive medicine depends on the clinician’s expertise, training, and exposure to different disorders, which is the traditional clinical model that predominates in child psychiatry. Empirical medicine relies on laboratory results, scans, scales, and other standardized tools.

Precision medicine occurs when a disorder can be precisely diagnosed and its cause understood, and when it can be treated with effective, evidence-based therapies. An example of this movement toward precision is Timothy syndrome (TS), a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by physical malformations, cardiac arrhythmias and structural heart defects, webbing of fingers and toes, and autism spectrum disorder. In the past, a child with TS would have been given a diagnosis of intellectual disability, or a specialist in developmental disorders might recognize the pattern of TS. It is now known that TS is caused by mutations in CACNA1C, the gene encoding the calcium channel Cav1.2α subunit, allowing precise diagnosis by genotyping.5

Although there are several tools that help clinicians assess symptoms of ADHD and BD, including rating scales such the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Rating Scale and Young Mania Rating Scale, none of these scales are diagnostic. Youngstrom et al6,7 have developed an evidence-based strategy to diagnose pediatric BD. This method uses a nomogram that takes into account the base rate of BD in a clinical setting and family history of BD.

We will describe and contrast the epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of pediatric BD from ADHD and use the Youngstrom nomogram to better define these patients. Although still far from precision medicine, the type of approach represents an ongoing effort in mental health care to increase diagnostic accuracy and improve treatment outcomes.

Pediatric bipolar disorder

Prevalence of pediatric BD is 1.8% (95% CI, 1.1% to 3.0%),8 which does not include sub-threshold cases of BD. ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) are 8 to 10 times more prevalent. For the purposes of the nomogram, the “base rate” is the rate at which a disorder occurs in different clinical settings. In general outpatient clinics, BD might occur 6% to 8% of the time, whereas in a county-run child psychiatry inpatient facility the rate is 11%.6 A reasonable rate in an outpatient pediatric setting is 6%.

Family history. In the Bipolar Offspring Study,9 the rate of BD in children of parents with BD was 13 times greater than that of controls, and the rate of anxiety and behavior disorders was approximately twice that of children of parents without BD (Table 1).9 This study evaluated 388 children of 233 parents with BD and 251 children of 143 demographically matched controls.

Clinical characteristics. Children and adolescents with BD typically manifest with what can be described as a “mood cycle”—a pronounced shift in mood and energy from one extreme to another. An example would be a child who wakes up with extreme silliness, high energy, and intrusive behavior that persists for several hours, then later becomes sad, depressed, and suicidal with no precipitant for either mood cycle.10 Pediatric patients with BD also exhibit other symptoms of mania during mood cycling periods.

Elevated or expansive mood. The child might have a mood that is inappropriately giddy, silly, elated, or euphoric. Often this mood will be present without reason and last for several hours. It may be distinguished from a transient cheerful mood by the intensity and duration of the episode. The child with BD may have little to no insight about the inappropriate nature of their elevated mood, when present.

Irritable mood. The child might become markedly belligerent or irritated with intense outbursts of anger, 2 to 3 times a day for several hours. An adolescent might appear extremely oppositional, belligerent, or hostile with parents and others.

Grandiosity or inflated self-esteem can be confused with brief childhood fantasies of increased capability. Typically, true grandiosity can manifest as assertion of great competency in all areas of life, which usually cannot be altered by contrary external evidence. Occasionally, this is bizarre and includes delusions of “super powers.” The child in a manic episode will not only assert that she can fly, but will jump off the garage roof to prove it.

Decreased need for sleep. The child may only require 4 to 5 hours of sleep a night during a manic episode without feeling fatigued or showing evidence of tiredness. Consider substance use in this differential diagnosis, especially in adolescents.

Increased talkativeness. Lack of inhibition to social norms may lead pediatric BD patients to blurt out answers during class or repeatedly be disciplined for talking to peers in class. Speech typically is rapid and pressured to the point where it might be continuous and seems to jump between loosely related subjects.

Flight of ideas or racing thoughts. The child or adolescent might report a subjective feeling that his thoughts are moving so rapidly that his speech cannot keep up. Often this is differentiated from rapid speech by the degree of rapidity the patient expresses loosely related topics that might seem completely unrelated to the listener.

Distractibility, short attention span. During a manic episode, the child or adolescent might report that it is impossible to pay attention to class or other outside events because of rapidly changing focus of their thoughts. This symptom must be carefully distinguished from the distractibility and inattention of ADHD, which typically is a more fixed and long-standing pattern rather than a brief episodic phenomenon in a manic or hypomanic episode.

Increase in goal-directed activity. During a mild manic episode, the child or adolescent may be capable of accomplishing a great deal of work. However, episodes that are more severe manifest as an individual starting numerous ambitious projects that she later is unable to complete.

Excessive risk-taking activities. The child or adolescent might become involved in forbidden, pleasurable activities that have a high risk of adverse consequences. This can manifest as hypersexual behavior, frequent fighting, increased recklessness, use of drugs and alcohol, shopping sprees, and reckless driving.

There are few studies comparing patients with comorbid BD and ADHD with patients with only ADHD. Geller et al11 compared 60 children with BD and ADHD (mean age, 10) to age- and sex-matched patients with ADHD and no mood disorder. Compared with children who had ADHD, those with BD exhibited significantly greater elevated mood, grandiosity, flight and/or racing of ideas, decreased need for sleep, and hypersexuality (Figure 1,11). Features common to both groups—and therefore not useful in differentiating the disorders—included irritability, hyperactivity, accelerated speech, and distractibility.

CASE REPORTIrritable and disruptiveBill, age 12, has been brought to see you by his mother because she is concerned about escalating behavior problems at home and school in the past several months. The school principal has called her about his obnoxious behavior with teachers and about other parents’ complaints that he has made unwanted sexual advances to girls who sit next to him in class.

Bill, who is in the 7th grade, is on the verge of being suspended for his inappropriate and disruptive behavior. His parents report that he is irritable around them and stays up all night, messaging his friends on the Internet from his iPad in his bedroom. They attribute his inappropriate sexual behavior to puberty and possibly to the Web sites he views.

Bill’s mother is concerned about his:

• increasing behavior problems during the last several months at home and school

• intensifying irritability and depressive symptoms

• staying up all night on the Internet, phoning friends, and doing projects

• frequent unprovoked, outbursts of rage occurring with increasing frequency and intensity (almost daily)

• moderate grandiosity, including telling the soccer coach and teachers how to do their jobs

• inappropriate sexual behavior, including kissing and touching female classmates.

During your history, you learn that Bill has been a bright and artistic child, with good academic performance. His peer relationships have been satisfactory, but not excellent—he tends to be “bossy” with his peers. He is medically healthy and not taking any medications. As part of your history, you also talk with Bill and his family about exposure to trauma or significant stressors, which they deny. You learn that Bill’s father was diagnosed with BD I at age 32.

Completing the nomogram developed by Youngstrom et al6,7 using these variables (see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for Figure 2)6,7 gives Bill a post-test probability of approximately 42%. The threshold for moving ahead with assessment and possible treatment, the “test-treatment threshold,” depends on your clinical setting.12,13 Our clinical experience is that, when the post-test probability exceeds 30%, further assessment for BD is warranted.

The next strategy is to look at Bill’s scores on externalizing behaviors using an instrument such as the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale. Few pediatric patients with BD will score low on externalizing behaviors.14 Bill scores in the clinically significant range for hyperactivity/impulsivity and positive on the screeners for ODD, conduct disorder (CD), and anxiety/depression.

You decide that Bill is at high risk of pediatric BD; he has a post-test probability of approximately 45%, and many externalizing behaviors on the Vanderbilt. You give Bill a diagnosis of BD I and ADHD and prescribe risperidone, 0.5 mg/d, which results in significant improvement in mood swings and other manic behaviors.

ADHD

Epidemiology. ADHD is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders in childhood, with prevalence estimates of 8% of U.S. children.15,16 Overall, boys are more likely to be assigned a diagnosis of ADHD than girls.15 Although ADHD often is diagnosed in early childhood, research is working to clarify the lifetime prevalence of ADHD into late adolescence and adulthood. Current estimates suggest that ADHD persists into adulthood in close to two-thirds of patients.17 However, the symptom presentation can change during adolescence and adulthood, with less overt hyperactivity and symptoms of impulsivity transitioning to risky behaviors involving trouble with the law, substance use, and sexual promiscuity.17

As in pediatric BD, comorbidity is common in ADHD, with uncomplicated ADHD being the exception rather than the rule. Recent studies have suggested that approximately two-thirds of children who have a diagnosis of ADHD have ≥1 comorbid diagnoses.15 Common comorbidities are similar to those seen in BD, including ODD, CD, anxiety disorders, depression, and learning disability. Several tools and resources are available to help clinicians navigate these issues within their practices.

Family history. Genetics appear to play a large role in ADHD, with twin studies suggesting inheritance of approximately 76%.18 Environmental factors contribute, either in the development of ADHD or in the exacerbation of an underlying familial predisposition. Interestingly, in children with BD, family history often is significant for several family members who have both ADHD and BD. However, in children with ADHD only, family history often reflects an absence of family members with BD.19 Although not diagnostic, this pattern can be helpful when considering a diagnosis of BD vs ADHD.

Clinical picture. ADHD often is recognized in childhood; DSM-5 criteria specify that symptoms be present before age 12 and persist for at least 6 months. This characterization of the timing of symptoms helps exclude behavioral disruptions related to external factors such as trauma (eg, death of a caregiver) or abuse. It also is important to note that symptoms might be present earlier but not come to attention clinically until a later age, perhaps because of increasing demands placed on the child by school, peer groups, and extracurricular activities. To make an ADHD diagnosis, symptoms must be present in >1 setting and interfere with functioning or development.

Core symptoms of ADHD include inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that are out of proportion to the child’s developmental level (Table 2).20 When considering diagnosis of ADHD, 6 of 9 symptoms for inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity must be present at a clinically significant level.

Three different ADHD presentations are recognized: combined, inattentive, and hyperactive impulsive. Children with predominant impulsive and hyperactive behaviors generally come to clinical attention at a younger age; inattentive symptoms often take longer to identify.

Children with ADHD have been noted to have lower tolerance for frustration, which might make anger outbursts and aggressive behavior more likely. Anger and aggression in ADHD often stem from impulsivity, rather than irritable mood seen with BD.18 Issues related to self-esteem, depression, substance use, and CD can contribute to symptoms of irritability, anger, and aggression that can occur in children with ADHD. Although these symptoms can overlap with those seen in children with BD, other core symptoms of ADHD will not be present.

ODD is one of the most common comorbidities among children with ADHD, and the combination of ODD and ADHD may be confused with BD. Children with ODD often are noted to exhibit a pattern of negative and defiant behavior that is out of proportion to what is seen in their peers and for their age and developmental level (Table 3).20 When considering an ODD diagnosis, 4 out of 8 symptoms must be present at a clinically significant level.

The following case highlights the potential similarities between ADHD/ODD and BD, with tips on how to distinguish them.

CASE REPORT

Angry and destructiveSam, age 7, has been given a diagnosis of ADHD, but his parents think that he isn’t improving with methylphenidate treatment. They are concerned that he has anger issues like his uncle, who has “bipolar disorder.”

Sam’s parents find that he gets frustrated easily and note that he has frequent short “meltdowns” and “mood swings.” During these episodes he yells, is aggressive towards others, and can be destructive. They are concerned because Sam will become angry quickly, then act as if nothing happened after the meltdown has blown over. Sam’s parents feel that he doesn’t listen to them and often argues when they make a request. His parents note that when they push harder, Sam digs in his heels, which can trigger his meltdowns.

Despite clearly disobeying his parents, Sam often says that things aren’t his fault and blames his parents or siblings instead. Sam seems to disagree with people often. His mother reports “if I say the water looks blue, he’ll say it’s green.” Often, Sam seems to argue or pester others to get a rise out of them. This is causing problems for Sam with his siblings and peers, and significant stress for his parents. Family history suggests that Sam’s uncle may have ADHD with CD or a substance use disorder, rather than true BD. Other than Sam’s uncle, there is no family history for BD.

Sam’s parents say that extended release methylphenidate, 20 mg/d, has helped with hyperactivity, but they are concerned that other symptoms have not improved. Aside from the symptoms listed above, Sam is described as a happy child. There is no history of trauma, and no symptoms of anxiety are noted. Sam sometimes gets “down” when things don’t go his way, but this lasts only for a few hours. Sam has a history of delayed sleep onset, which responded well to melatonin. No other symptoms that suggest mania are described.

You complete the pediatric bipolar nomogram (Figure 3)6,7 and Sam’s parents complete a Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale. At first, Sam seems to have several factors that might indicate BD: aggressive behavior, mood swings, sleep problems, and, possibly, a family history of BD.

However, a careful history provides several clues that Sam has a comorbid diagnosis of ODD. Sam is exhibiting the classic pattern of negativist behavior seen in children with ODD. In contrast to the episodic pattern of BD, these symptoms are prevalent and persistent, and manifest as an overall pattern of functioning. Impulsivity seen in children with ADHD can complicate the picture, but again appears as a consistent pattern rather than bouts of irritability. Sam’s core symptoms of ADHD (hyperactivity) improved with methylphenidate, but the underlying symptoms of ODD persisted.

Sleep problems are common in children who have ADHD and BD, but Sam’s delayed sleep onset responded to melatonin, whereas the insomnia seen in BD often is refractory to lower-intensity interventions, such as melatonin. Taking a careful family history led you to believe that BD in the family is unlikely. Although this type of detail may not always be available, it can be helpful to ask about mental health symptoms that seem to “run in the family.”

Bottom Line

Distinguishing the child who has bipolar disorder from one who has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder can be challenging. A careful history helps ensure that you are on the path toward understanding the diagnostic possibilities. Tools such as the Vanderbilt Rating Scale can further clarify possible diagnoses, and the nomogram approach can provide even more predictive information when considering a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Related Resources

• Children and Adults with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD). www.chadd.org.

• American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Facts for Families. www.aacap.org/cs/root/facts_for_families/ facts_for_families.

• Froehlich TE, Delgado SV, Anixt JS. Expanding medication options for pediatric ADHD. Current Psychiatry. 2013;(12)12:20-29.

• Passarotti AM, Pavuluri MN. Brain functional domains inform therapeutic interventions in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and pediatric bipolar disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(6):897-914.

Drug Brand Names

Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Methylin, Metadate CD, Metadate ER, Methylin ER, Ritalin LA, Ritalin SR, Concerta, Quillivant XR, Daytrana

Risperidone • Risperdal

Differentiating the irritable, oppositional child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) from the child with bipolar disorder (BD) often is difficult. To make matters more complicated, 50% to 70% of patients with BD have comorbid ADHD.1,2 Accordingly, clinicians are often faced with the moody, irritable, disruptive child whose parents want to know if he (she) is “bipolar” to try to deal with oppositional and mood behaviors.

In this article, we present an approach that will help you distinguish these 2 disorders from each other.

Precision medicineThere is a lack of evidence-based methods for diagnosing psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents. DSM-5 provides clinicians with diagnostic checklists that rely on the clinician’s judgment and training in evaluating a patient.3 In The innovator’s prescription: a disruptive solution for health care, Christensen et al4 describe how medicine is moving from “intuitive medicine” to empirical medicine and toward “precision medicine.” Intuitive medicine depends on the clinician’s expertise, training, and exposure to different disorders, which is the traditional clinical model that predominates in child psychiatry. Empirical medicine relies on laboratory results, scans, scales, and other standardized tools.

Precision medicine occurs when a disorder can be precisely diagnosed and its cause understood, and when it can be treated with effective, evidence-based therapies. An example of this movement toward precision is Timothy syndrome (TS), a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by physical malformations, cardiac arrhythmias and structural heart defects, webbing of fingers and toes, and autism spectrum disorder. In the past, a child with TS would have been given a diagnosis of intellectual disability, or a specialist in developmental disorders might recognize the pattern of TS. It is now known that TS is caused by mutations in CACNA1C, the gene encoding the calcium channel Cav1.2α subunit, allowing precise diagnosis by genotyping.5

Although there are several tools that help clinicians assess symptoms of ADHD and BD, including rating scales such the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Rating Scale and Young Mania Rating Scale, none of these scales are diagnostic. Youngstrom et al6,7 have developed an evidence-based strategy to diagnose pediatric BD. This method uses a nomogram that takes into account the base rate of BD in a clinical setting and family history of BD.

We will describe and contrast the epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of pediatric BD from ADHD and use the Youngstrom nomogram to better define these patients. Although still far from precision medicine, the type of approach represents an ongoing effort in mental health care to increase diagnostic accuracy and improve treatment outcomes.

Pediatric bipolar disorder

Prevalence of pediatric BD is 1.8% (95% CI, 1.1% to 3.0%),8 which does not include sub-threshold cases of BD. ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) are 8 to 10 times more prevalent. For the purposes of the nomogram, the “base rate” is the rate at which a disorder occurs in different clinical settings. In general outpatient clinics, BD might occur 6% to 8% of the time, whereas in a county-run child psychiatry inpatient facility the rate is 11%.6 A reasonable rate in an outpatient pediatric setting is 6%.

Family history. In the Bipolar Offspring Study,9 the rate of BD in children of parents with BD was 13 times greater than that of controls, and the rate of anxiety and behavior disorders was approximately twice that of children of parents without BD (Table 1).9 This study evaluated 388 children of 233 parents with BD and 251 children of 143 demographically matched controls.

Clinical characteristics. Children and adolescents with BD typically manifest with what can be described as a “mood cycle”—a pronounced shift in mood and energy from one extreme to another. An example would be a child who wakes up with extreme silliness, high energy, and intrusive behavior that persists for several hours, then later becomes sad, depressed, and suicidal with no precipitant for either mood cycle.10 Pediatric patients with BD also exhibit other symptoms of mania during mood cycling periods.

Elevated or expansive mood. The child might have a mood that is inappropriately giddy, silly, elated, or euphoric. Often this mood will be present without reason and last for several hours. It may be distinguished from a transient cheerful mood by the intensity and duration of the episode. The child with BD may have little to no insight about the inappropriate nature of their elevated mood, when present.

Irritable mood. The child might become markedly belligerent or irritated with intense outbursts of anger, 2 to 3 times a day for several hours. An adolescent might appear extremely oppositional, belligerent, or hostile with parents and others.

Grandiosity or inflated self-esteem can be confused with brief childhood fantasies of increased capability. Typically, true grandiosity can manifest as assertion of great competency in all areas of life, which usually cannot be altered by contrary external evidence. Occasionally, this is bizarre and includes delusions of “super powers.” The child in a manic episode will not only assert that she can fly, but will jump off the garage roof to prove it.

Decreased need for sleep. The child may only require 4 to 5 hours of sleep a night during a manic episode without feeling fatigued or showing evidence of tiredness. Consider substance use in this differential diagnosis, especially in adolescents.

Increased talkativeness. Lack of inhibition to social norms may lead pediatric BD patients to blurt out answers during class or repeatedly be disciplined for talking to peers in class. Speech typically is rapid and pressured to the point where it might be continuous and seems to jump between loosely related subjects.

Flight of ideas or racing thoughts. The child or adolescent might report a subjective feeling that his thoughts are moving so rapidly that his speech cannot keep up. Often this is differentiated from rapid speech by the degree of rapidity the patient expresses loosely related topics that might seem completely unrelated to the listener.

Distractibility, short attention span. During a manic episode, the child or adolescent might report that it is impossible to pay attention to class or other outside events because of rapidly changing focus of their thoughts. This symptom must be carefully distinguished from the distractibility and inattention of ADHD, which typically is a more fixed and long-standing pattern rather than a brief episodic phenomenon in a manic or hypomanic episode.

Increase in goal-directed activity. During a mild manic episode, the child or adolescent may be capable of accomplishing a great deal of work. However, episodes that are more severe manifest as an individual starting numerous ambitious projects that she later is unable to complete.

Excessive risk-taking activities. The child or adolescent might become involved in forbidden, pleasurable activities that have a high risk of adverse consequences. This can manifest as hypersexual behavior, frequent fighting, increased recklessness, use of drugs and alcohol, shopping sprees, and reckless driving.

There are few studies comparing patients with comorbid BD and ADHD with patients with only ADHD. Geller et al11 compared 60 children with BD and ADHD (mean age, 10) to age- and sex-matched patients with ADHD and no mood disorder. Compared with children who had ADHD, those with BD exhibited significantly greater elevated mood, grandiosity, flight and/or racing of ideas, decreased need for sleep, and hypersexuality (Figure 1,11). Features common to both groups—and therefore not useful in differentiating the disorders—included irritability, hyperactivity, accelerated speech, and distractibility.

CASE REPORTIrritable and disruptiveBill, age 12, has been brought to see you by his mother because she is concerned about escalating behavior problems at home and school in the past several months. The school principal has called her about his obnoxious behavior with teachers and about other parents’ complaints that he has made unwanted sexual advances to girls who sit next to him in class.

Bill, who is in the 7th grade, is on the verge of being suspended for his inappropriate and disruptive behavior. His parents report that he is irritable around them and stays up all night, messaging his friends on the Internet from his iPad in his bedroom. They attribute his inappropriate sexual behavior to puberty and possibly to the Web sites he views.

Bill’s mother is concerned about his:

• increasing behavior problems during the last several months at home and school

• intensifying irritability and depressive symptoms

• staying up all night on the Internet, phoning friends, and doing projects

• frequent unprovoked, outbursts of rage occurring with increasing frequency and intensity (almost daily)

• moderate grandiosity, including telling the soccer coach and teachers how to do their jobs

• inappropriate sexual behavior, including kissing and touching female classmates.

During your history, you learn that Bill has been a bright and artistic child, with good academic performance. His peer relationships have been satisfactory, but not excellent—he tends to be “bossy” with his peers. He is medically healthy and not taking any medications. As part of your history, you also talk with Bill and his family about exposure to trauma or significant stressors, which they deny. You learn that Bill’s father was diagnosed with BD I at age 32.

Completing the nomogram developed by Youngstrom et al6,7 using these variables (see this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for Figure 2)6,7 gives Bill a post-test probability of approximately 42%. The threshold for moving ahead with assessment and possible treatment, the “test-treatment threshold,” depends on your clinical setting.12,13 Our clinical experience is that, when the post-test probability exceeds 30%, further assessment for BD is warranted.

The next strategy is to look at Bill’s scores on externalizing behaviors using an instrument such as the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale. Few pediatric patients with BD will score low on externalizing behaviors.14 Bill scores in the clinically significant range for hyperactivity/impulsivity and positive on the screeners for ODD, conduct disorder (CD), and anxiety/depression.

You decide that Bill is at high risk of pediatric BD; he has a post-test probability of approximately 45%, and many externalizing behaviors on the Vanderbilt. You give Bill a diagnosis of BD I and ADHD and prescribe risperidone, 0.5 mg/d, which results in significant improvement in mood swings and other manic behaviors.

ADHD

Epidemiology. ADHD is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders in childhood, with prevalence estimates of 8% of U.S. children.15,16 Overall, boys are more likely to be assigned a diagnosis of ADHD than girls.15 Although ADHD often is diagnosed in early childhood, research is working to clarify the lifetime prevalence of ADHD into late adolescence and adulthood. Current estimates suggest that ADHD persists into adulthood in close to two-thirds of patients.17 However, the symptom presentation can change during adolescence and adulthood, with less overt hyperactivity and symptoms of impulsivity transitioning to risky behaviors involving trouble with the law, substance use, and sexual promiscuity.17

As in pediatric BD, comorbidity is common in ADHD, with uncomplicated ADHD being the exception rather than the rule. Recent studies have suggested that approximately two-thirds of children who have a diagnosis of ADHD have ≥1 comorbid diagnoses.15 Common comorbidities are similar to those seen in BD, including ODD, CD, anxiety disorders, depression, and learning disability. Several tools and resources are available to help clinicians navigate these issues within their practices.

Family history. Genetics appear to play a large role in ADHD, with twin studies suggesting inheritance of approximately 76%.18 Environmental factors contribute, either in the development of ADHD or in the exacerbation of an underlying familial predisposition. Interestingly, in children with BD, family history often is significant for several family members who have both ADHD and BD. However, in children with ADHD only, family history often reflects an absence of family members with BD.19 Although not diagnostic, this pattern can be helpful when considering a diagnosis of BD vs ADHD.

Clinical picture. ADHD often is recognized in childhood; DSM-5 criteria specify that symptoms be present before age 12 and persist for at least 6 months. This characterization of the timing of symptoms helps exclude behavioral disruptions related to external factors such as trauma (eg, death of a caregiver) or abuse. It also is important to note that symptoms might be present earlier but not come to attention clinically until a later age, perhaps because of increasing demands placed on the child by school, peer groups, and extracurricular activities. To make an ADHD diagnosis, symptoms must be present in >1 setting and interfere with functioning or development.

Core symptoms of ADHD include inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that are out of proportion to the child’s developmental level (Table 2).20 When considering diagnosis of ADHD, 6 of 9 symptoms for inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity must be present at a clinically significant level.

Three different ADHD presentations are recognized: combined, inattentive, and hyperactive impulsive. Children with predominant impulsive and hyperactive behaviors generally come to clinical attention at a younger age; inattentive symptoms often take longer to identify.

Children with ADHD have been noted to have lower tolerance for frustration, which might make anger outbursts and aggressive behavior more likely. Anger and aggression in ADHD often stem from impulsivity, rather than irritable mood seen with BD.18 Issues related to self-esteem, depression, substance use, and CD can contribute to symptoms of irritability, anger, and aggression that can occur in children with ADHD. Although these symptoms can overlap with those seen in children with BD, other core symptoms of ADHD will not be present.

ODD is one of the most common comorbidities among children with ADHD, and the combination of ODD and ADHD may be confused with BD. Children with ODD often are noted to exhibit a pattern of negative and defiant behavior that is out of proportion to what is seen in their peers and for their age and developmental level (Table 3).20 When considering an ODD diagnosis, 4 out of 8 symptoms must be present at a clinically significant level.

The following case highlights the potential similarities between ADHD/ODD and BD, with tips on how to distinguish them.

CASE REPORT

Angry and destructiveSam, age 7, has been given a diagnosis of ADHD, but his parents think that he isn’t improving with methylphenidate treatment. They are concerned that he has anger issues like his uncle, who has “bipolar disorder.”

Sam’s parents find that he gets frustrated easily and note that he has frequent short “meltdowns” and “mood swings.” During these episodes he yells, is aggressive towards others, and can be destructive. They are concerned because Sam will become angry quickly, then act as if nothing happened after the meltdown has blown over. Sam’s parents feel that he doesn’t listen to them and often argues when they make a request. His parents note that when they push harder, Sam digs in his heels, which can trigger his meltdowns.

Despite clearly disobeying his parents, Sam often says that things aren’t his fault and blames his parents or siblings instead. Sam seems to disagree with people often. His mother reports “if I say the water looks blue, he’ll say it’s green.” Often, Sam seems to argue or pester others to get a rise out of them. This is causing problems for Sam with his siblings and peers, and significant stress for his parents. Family history suggests that Sam’s uncle may have ADHD with CD or a substance use disorder, rather than true BD. Other than Sam’s uncle, there is no family history for BD.

Sam’s parents say that extended release methylphenidate, 20 mg/d, has helped with hyperactivity, but they are concerned that other symptoms have not improved. Aside from the symptoms listed above, Sam is described as a happy child. There is no history of trauma, and no symptoms of anxiety are noted. Sam sometimes gets “down” when things don’t go his way, but this lasts only for a few hours. Sam has a history of delayed sleep onset, which responded well to melatonin. No other symptoms that suggest mania are described.

You complete the pediatric bipolar nomogram (Figure 3)6,7 and Sam’s parents complete a Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Parent Rating Scale. At first, Sam seems to have several factors that might indicate BD: aggressive behavior, mood swings, sleep problems, and, possibly, a family history of BD.

However, a careful history provides several clues that Sam has a comorbid diagnosis of ODD. Sam is exhibiting the classic pattern of negativist behavior seen in children with ODD. In contrast to the episodic pattern of BD, these symptoms are prevalent and persistent, and manifest as an overall pattern of functioning. Impulsivity seen in children with ADHD can complicate the picture, but again appears as a consistent pattern rather than bouts of irritability. Sam’s core symptoms of ADHD (hyperactivity) improved with methylphenidate, but the underlying symptoms of ODD persisted.

Sleep problems are common in children who have ADHD and BD, but Sam’s delayed sleep onset responded to melatonin, whereas the insomnia seen in BD often is refractory to lower-intensity interventions, such as melatonin. Taking a careful family history led you to believe that BD in the family is unlikely. Although this type of detail may not always be available, it can be helpful to ask about mental health symptoms that seem to “run in the family.”

Bottom Line

Distinguishing the child who has bipolar disorder from one who has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder can be challenging. A careful history helps ensure that you are on the path toward understanding the diagnostic possibilities. Tools such as the Vanderbilt Rating Scale can further clarify possible diagnoses, and the nomogram approach can provide even more predictive information when considering a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Related Resources

• Children and Adults with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD). www.chadd.org.

• American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Facts for Families. www.aacap.org/cs/root/facts_for_families/ facts_for_families.

• Froehlich TE, Delgado SV, Anixt JS. Expanding medication options for pediatric ADHD. Current Psychiatry. 2013;(12)12:20-29.

• Passarotti AM, Pavuluri MN. Brain functional domains inform therapeutic interventions in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and pediatric bipolar disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(6):897-914.

Drug Brand Names

Methylphenidate • Ritalin, Methylin, Metadate CD, Metadate ER, Methylin ER, Ritalin LA, Ritalin SR, Concerta, Quillivant XR, Daytrana

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Wozniak J, et al. Is comorbidity with ADHD a marker for juvenile-onset mania? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(8):1046-1055.

2. West SA, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adolescent mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(2):271-273.

3. McHugh PR, Slavney PR. Mental illness–comprehensive evaluation or checklist? N Engl J Med. 2012;366(20): 1853-1855.

4. Christensen CM, Grossman JH, Hwang J. The innovator’s prescription: a disruptive solution for health care. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

5. Yazawa M, Hsueh B, Jia X, et al. Using induced pluripotent stem cells to investigate cardiac phenotypes in Timothy syndrome. Nature. 2011;471(7337):230-234.

6. Youngstrom EA, Duax J. Evidence-based assessment of pediatric bipolar disorder, part I: base rate and family history. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(7): 712-717.

7. Youngstrom EA, Jenkins MM, Doss AJ, et al. Evidence-based assessment strategies for pediatric bipolar disorder. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2012;49(1):15-27.

8. Van Meter AR, Moreira AL, Youngstrom EA. Meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(9):1250-1256.

9. Birmaher B, Axelson D, Monk K, et al. Lifetime psychiatric disorders in school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(3):287-296.

10. Youngstrom EA, Birmaher B, Findling RL. Pediatric bipolar disorder: validity, phenomenology, and recommendations for diagnosis. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10 (1 pt 2):194-214.

11. Geller B, Warner K, Williams M, et al. Prepubertal and young adolescent bipolarity versus ADHD: assessment and validity using the WASH-U-KSADS, CBCL and TRF. J Affect Disord. 1998;51(2):93-100.

12. Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Guyatt GH, et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XV. How to use an article about disease probability for differential diagnosis. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1999;281(13):1214-1219.

13. Nease RF Jr, Owens DK, Sox HC Jr. Threshold analysis using diagnostic tests with multiple results. Med Decis Making. 1989;9(2):91-103.

14. Youngstrom EA, Youngstrom JK. Evidence-based assessment of pediatric bipolar disorder, Part II: incorporating information from behavior checklists. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(8):823-828.

15. Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001-2004 NHANES. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):75-81.

16. Larson K, Russ SA, Kahn RS, et al. Patterns of comorbidity, functioning, and service use for US children with ADHD, 2007. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):462-470.

17. Simon V, Czobor P, Bálint S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(3):204-211.

18. Biederman J, Faraone SV. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2005;366(9481):237-248.

19. Sood AB, Razdan A, Weller EB, et al. How to differentiate bipolar disorder from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and other common psychiatric disorders: a guide for clinicians. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2005;7(2): 98-103.

20. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

1. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Wozniak J, et al. Is comorbidity with ADHD a marker for juvenile-onset mania? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(8):1046-1055.

2. West SA, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adolescent mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(2):271-273.

3. McHugh PR, Slavney PR. Mental illness–comprehensive evaluation or checklist? N Engl J Med. 2012;366(20): 1853-1855.

4. Christensen CM, Grossman JH, Hwang J. The innovator’s prescription: a disruptive solution for health care. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

5. Yazawa M, Hsueh B, Jia X, et al. Using induced pluripotent stem cells to investigate cardiac phenotypes in Timothy syndrome. Nature. 2011;471(7337):230-234.

6. Youngstrom EA, Duax J. Evidence-based assessment of pediatric bipolar disorder, part I: base rate and family history. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(7): 712-717.

7. Youngstrom EA, Jenkins MM, Doss AJ, et al. Evidence-based assessment strategies for pediatric bipolar disorder. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2012;49(1):15-27.

8. Van Meter AR, Moreira AL, Youngstrom EA. Meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(9):1250-1256.

9. Birmaher B, Axelson D, Monk K, et al. Lifetime psychiatric disorders in school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(3):287-296.

10. Youngstrom EA, Birmaher B, Findling RL. Pediatric bipolar disorder: validity, phenomenology, and recommendations for diagnosis. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10 (1 pt 2):194-214.

11. Geller B, Warner K, Williams M, et al. Prepubertal and young adolescent bipolarity versus ADHD: assessment and validity using the WASH-U-KSADS, CBCL and TRF. J Affect Disord. 1998;51(2):93-100.

12. Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Guyatt GH, et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XV. How to use an article about disease probability for differential diagnosis. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1999;281(13):1214-1219.

13. Nease RF Jr, Owens DK, Sox HC Jr. Threshold analysis using diagnostic tests with multiple results. Med Decis Making. 1989;9(2):91-103.

14. Youngstrom EA, Youngstrom JK. Evidence-based assessment of pediatric bipolar disorder, Part II: incorporating information from behavior checklists. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44(8):823-828.

15. Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001-2004 NHANES. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):75-81.

16. Larson K, Russ SA, Kahn RS, et al. Patterns of comorbidity, functioning, and service use for US children with ADHD, 2007. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):462-470.

17. Simon V, Czobor P, Bálint S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(3):204-211.

18. Biederman J, Faraone SV. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2005;366(9481):237-248.

19. Sood AB, Razdan A, Weller EB, et al. How to differentiate bipolar disorder from attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and other common psychiatric disorders: a guide for clinicians. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2005;7(2): 98-103.

20. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.