User login

Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis–associated uveitis (JIA-U) are significantly more likely to experience a flare in their eye disease if their arthritis is also worsening, a team of U.S.-based researchers has found.

In a longitudinal cohort study, children with active arthritis at the time of a routine rheumatology assessment had an almost 2.5-fold increased risk of also having active uveitis 45 days before or after the assessment than did children whose arthritis was not flaring at the rheumatology assessment.

“We demonstrate that the two diseases often run parallel courses,” corresponding author Emily J. Liebling, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and associates state in Arthritis Care & Research, noting that the magnitude of the association is striking.

“Although there are known risk factors associated with uveitis development in children with JIA, less data are available about factors associated with uveitis flare or activity,” said Sheila T. Angeles-Han, MD, MSc, of the departments of pediatrics and ophthalmology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center who commented on the study in an interview.

“If proven, this knowledge has the potential to impact practice patterns and current guidelines wherein a pediatric rheumatologist who evaluates a child with JIA-associated uveitis and finds active arthritis would request an expedited ophthalmic examination,” Dr. Angeles-Han suggested.

Dr. Angeles-Han led the development of the first American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Screening, Monitoring, and Treatment of JIA-Associated Uveitis, which recommends regular screening for uveitis in all children with JIA. Children found to have uveitis should then be screened at least every 3 months, and more frequently if they are taking glucocorticoids and treatment is being tapered.

JIA-associated uveitis accounts for around 20%-40% of all cases of noninfectious childhood eye inflammation, and it can run an insidious and chronic course.

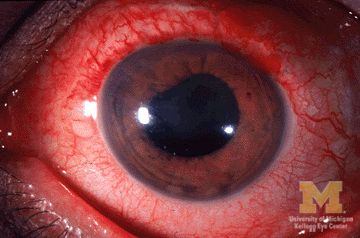

“Children with acute anterior uveitis are symptomatic and tend to have a painful red eye, thus prompting an ophthalmic evaluation,” Dr. Angeles-Han explained. “This is different from children with chronic anterior uveitis who tend not to have any symptoms, thus a screening examination is critical to detect ocular inflammation.”

While the ACR/AF guideline distinguishes between acute and chronic uveitis, Dr. Liebling and colleagues explain that they did not because their experience shows that “even patients with chronic anterior uveitis, typically thought to have silent disease, may exhibit symptoms of eye pain, redness, vision changes, and photophobia.”

Conversely, they say “the JIA subtypes usually associated with acute anterior uveitis may instead manifest as asymptomatic eye disease.”

For their study, Dr. Liebling and coinvestigators examined the records of children seen at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia over a 6.5-year period. For inclusion, children had to have a physician diagnosis of JIA of any subtype and a history of uveitis.

A total of 98 children were included in the retrospective evaluation; the median age at diagnosis of JIA was 3.3 years, and the median age at first uveitis diagnosis was 5.1 years. The majority (82%) were female, 69% were antinuclear antibody (ANA) positive, and 60% had oligoarthritis – all of which have been associated with having a higher risk for developing uveitis.

However, independent of these and several other factors, the probability of having active uveitis within 45 days of a rheumatology assessment was 65% in those with active arthritis versus 42% for those with no active joints.

Their data are based on 1,229 rheumatology visits that occurred between 2013 and 2019, with a median of 13 visits per patient. Overall, arthritis was defined as being active in 17% of visits, and active uveitis was observed in 18% of rheumatology visits.

Concordance between arthritis and uveitis activity was observed 73% of the time, the researchers reported. A sensitivity analysis that excluded children with the enthesitis-related arthritis subtype of JIA, who may not undergo frequent eye exams, did not change their findings.

Decreased odds of active uveitis at any time point were seen with the use of combination biologic and nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Years from uveitis diagnosis was also associated with lower odds of active uveitis over time.

Other factors associated with lower odds of uveitis were female sex, HLA-B27 positivity, and having any subtype of JIA other than the oligoarticular subtype.

Dr. Liebling and coinvestigators concluded that, contrary to the historical dogma, arthritis and uveitis do not run distinct and unrelated courses: “In patients with JIA-U, there is a significant temporal association between arthritis and uveitis disease activity.”

The study was sponsored by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Rheumatology Research Fund. The investigators for the study had no financial support from commercial sources or any other potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Angeles-Han had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Liebling EJ et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2020 Oct 12. doi: 10.1002/acr.24483.

Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis–associated uveitis (JIA-U) are significantly more likely to experience a flare in their eye disease if their arthritis is also worsening, a team of U.S.-based researchers has found.

In a longitudinal cohort study, children with active arthritis at the time of a routine rheumatology assessment had an almost 2.5-fold increased risk of also having active uveitis 45 days before or after the assessment than did children whose arthritis was not flaring at the rheumatology assessment.

“We demonstrate that the two diseases often run parallel courses,” corresponding author Emily J. Liebling, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and associates state in Arthritis Care & Research, noting that the magnitude of the association is striking.

“Although there are known risk factors associated with uveitis development in children with JIA, less data are available about factors associated with uveitis flare or activity,” said Sheila T. Angeles-Han, MD, MSc, of the departments of pediatrics and ophthalmology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center who commented on the study in an interview.

“If proven, this knowledge has the potential to impact practice patterns and current guidelines wherein a pediatric rheumatologist who evaluates a child with JIA-associated uveitis and finds active arthritis would request an expedited ophthalmic examination,” Dr. Angeles-Han suggested.

Dr. Angeles-Han led the development of the first American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Screening, Monitoring, and Treatment of JIA-Associated Uveitis, which recommends regular screening for uveitis in all children with JIA. Children found to have uveitis should then be screened at least every 3 months, and more frequently if they are taking glucocorticoids and treatment is being tapered.

JIA-associated uveitis accounts for around 20%-40% of all cases of noninfectious childhood eye inflammation, and it can run an insidious and chronic course.

“Children with acute anterior uveitis are symptomatic and tend to have a painful red eye, thus prompting an ophthalmic evaluation,” Dr. Angeles-Han explained. “This is different from children with chronic anterior uveitis who tend not to have any symptoms, thus a screening examination is critical to detect ocular inflammation.”

While the ACR/AF guideline distinguishes between acute and chronic uveitis, Dr. Liebling and colleagues explain that they did not because their experience shows that “even patients with chronic anterior uveitis, typically thought to have silent disease, may exhibit symptoms of eye pain, redness, vision changes, and photophobia.”

Conversely, they say “the JIA subtypes usually associated with acute anterior uveitis may instead manifest as asymptomatic eye disease.”

For their study, Dr. Liebling and coinvestigators examined the records of children seen at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia over a 6.5-year period. For inclusion, children had to have a physician diagnosis of JIA of any subtype and a history of uveitis.

A total of 98 children were included in the retrospective evaluation; the median age at diagnosis of JIA was 3.3 years, and the median age at first uveitis diagnosis was 5.1 years. The majority (82%) were female, 69% were antinuclear antibody (ANA) positive, and 60% had oligoarthritis – all of which have been associated with having a higher risk for developing uveitis.

However, independent of these and several other factors, the probability of having active uveitis within 45 days of a rheumatology assessment was 65% in those with active arthritis versus 42% for those with no active joints.

Their data are based on 1,229 rheumatology visits that occurred between 2013 and 2019, with a median of 13 visits per patient. Overall, arthritis was defined as being active in 17% of visits, and active uveitis was observed in 18% of rheumatology visits.

Concordance between arthritis and uveitis activity was observed 73% of the time, the researchers reported. A sensitivity analysis that excluded children with the enthesitis-related arthritis subtype of JIA, who may not undergo frequent eye exams, did not change their findings.

Decreased odds of active uveitis at any time point were seen with the use of combination biologic and nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Years from uveitis diagnosis was also associated with lower odds of active uveitis over time.

Other factors associated with lower odds of uveitis were female sex, HLA-B27 positivity, and having any subtype of JIA other than the oligoarticular subtype.

Dr. Liebling and coinvestigators concluded that, contrary to the historical dogma, arthritis and uveitis do not run distinct and unrelated courses: “In patients with JIA-U, there is a significant temporal association between arthritis and uveitis disease activity.”

The study was sponsored by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Rheumatology Research Fund. The investigators for the study had no financial support from commercial sources or any other potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Angeles-Han had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Liebling EJ et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2020 Oct 12. doi: 10.1002/acr.24483.

Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis–associated uveitis (JIA-U) are significantly more likely to experience a flare in their eye disease if their arthritis is also worsening, a team of U.S.-based researchers has found.

In a longitudinal cohort study, children with active arthritis at the time of a routine rheumatology assessment had an almost 2.5-fold increased risk of also having active uveitis 45 days before or after the assessment than did children whose arthritis was not flaring at the rheumatology assessment.

“We demonstrate that the two diseases often run parallel courses,” corresponding author Emily J. Liebling, MD, of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and associates state in Arthritis Care & Research, noting that the magnitude of the association is striking.

“Although there are known risk factors associated with uveitis development in children with JIA, less data are available about factors associated with uveitis flare or activity,” said Sheila T. Angeles-Han, MD, MSc, of the departments of pediatrics and ophthalmology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center who commented on the study in an interview.

“If proven, this knowledge has the potential to impact practice patterns and current guidelines wherein a pediatric rheumatologist who evaluates a child with JIA-associated uveitis and finds active arthritis would request an expedited ophthalmic examination,” Dr. Angeles-Han suggested.

Dr. Angeles-Han led the development of the first American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the Screening, Monitoring, and Treatment of JIA-Associated Uveitis, which recommends regular screening for uveitis in all children with JIA. Children found to have uveitis should then be screened at least every 3 months, and more frequently if they are taking glucocorticoids and treatment is being tapered.

JIA-associated uveitis accounts for around 20%-40% of all cases of noninfectious childhood eye inflammation, and it can run an insidious and chronic course.

“Children with acute anterior uveitis are symptomatic and tend to have a painful red eye, thus prompting an ophthalmic evaluation,” Dr. Angeles-Han explained. “This is different from children with chronic anterior uveitis who tend not to have any symptoms, thus a screening examination is critical to detect ocular inflammation.”

While the ACR/AF guideline distinguishes between acute and chronic uveitis, Dr. Liebling and colleagues explain that they did not because their experience shows that “even patients with chronic anterior uveitis, typically thought to have silent disease, may exhibit symptoms of eye pain, redness, vision changes, and photophobia.”

Conversely, they say “the JIA subtypes usually associated with acute anterior uveitis may instead manifest as asymptomatic eye disease.”

For their study, Dr. Liebling and coinvestigators examined the records of children seen at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia over a 6.5-year period. For inclusion, children had to have a physician diagnosis of JIA of any subtype and a history of uveitis.

A total of 98 children were included in the retrospective evaluation; the median age at diagnosis of JIA was 3.3 years, and the median age at first uveitis diagnosis was 5.1 years. The majority (82%) were female, 69% were antinuclear antibody (ANA) positive, and 60% had oligoarthritis – all of which have been associated with having a higher risk for developing uveitis.

However, independent of these and several other factors, the probability of having active uveitis within 45 days of a rheumatology assessment was 65% in those with active arthritis versus 42% for those with no active joints.

Their data are based on 1,229 rheumatology visits that occurred between 2013 and 2019, with a median of 13 visits per patient. Overall, arthritis was defined as being active in 17% of visits, and active uveitis was observed in 18% of rheumatology visits.

Concordance between arthritis and uveitis activity was observed 73% of the time, the researchers reported. A sensitivity analysis that excluded children with the enthesitis-related arthritis subtype of JIA, who may not undergo frequent eye exams, did not change their findings.

Decreased odds of active uveitis at any time point were seen with the use of combination biologic and nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Years from uveitis diagnosis was also associated with lower odds of active uveitis over time.

Other factors associated with lower odds of uveitis were female sex, HLA-B27 positivity, and having any subtype of JIA other than the oligoarticular subtype.

Dr. Liebling and coinvestigators concluded that, contrary to the historical dogma, arthritis and uveitis do not run distinct and unrelated courses: “In patients with JIA-U, there is a significant temporal association between arthritis and uveitis disease activity.”

The study was sponsored by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Rheumatology Research Fund. The investigators for the study had no financial support from commercial sources or any other potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Angeles-Han had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SOURCE: Liebling EJ et al. Arthritis Care Res. 2020 Oct 12. doi: 10.1002/acr.24483.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH