User login

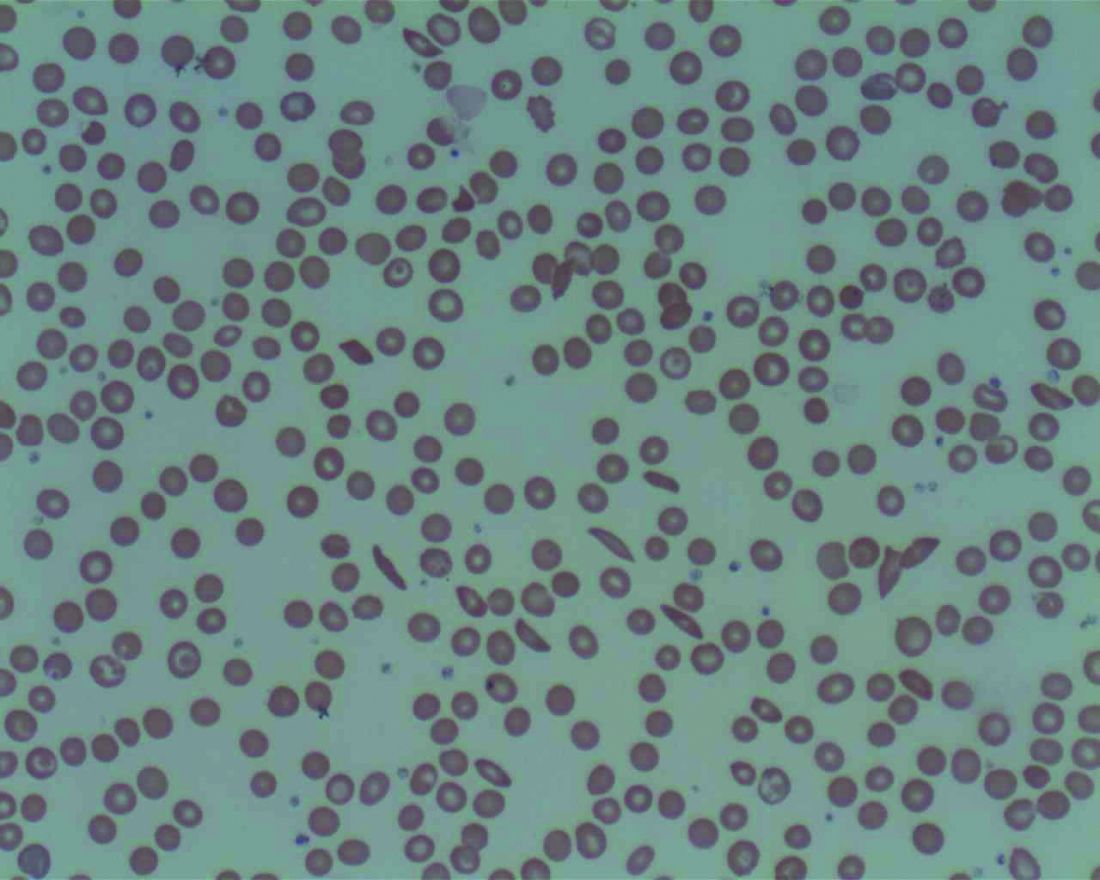

The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine have just released a 522-page report, but it’s not the usual compilation of guidelines for treatment of a disease. Instead, the authors of “Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action” argue in stark terms that the American society has colossally failed individuals living with sickle cell disease (SCD), who are mostly Black or Brown. A dramatic overhaul of the country’s medical and societal priorities is needed to turn things around to improve health and longevity among this rare disease population.

The findings from the NASEM report are explicit: “There has been substantial success in increasing the survival of children with SCD, but this success had not been translated to similar success as they become adults.” One factor posited to contribute to the slow progress in the improvement of quality and quantity of life for adults living with this disease is the fact that “SCD is largely a disease of African Americans, and as such exists in a context of racial discrimination, health and other societal disparities, mistrust of the health care system, and the effects of poverty.” The report also cites the substantial evidence that those with SCD may receive poorer quality of care.

The report’s 14 authors were made up of an ad hoc committee formed at the request of the Department of Health & Human Services’ Office of Minority Health. The office asked NASEM to convene the committee to develop a strategic plan and blueprint for the United States and others regarding SCD.

The NASEM SCD committee members “realized that we can’t address the medical components of SCD if we don’t explore societal issues and why it’s been so hard to get good care for people with sickle cell disease,” hematologist and report coauthor Ifeyinwa (Ify) Osunkwo, MD, professor of medicine and pediatrics at Atrium Health and director of the Sickle Cell Disease Enterprise, Levine Cancer Institute, Charlotte, N.C., said in an interview. Dr. Osunkwo is also the medical editor of Hematology News.

“After almost a year of meetings and digging into the background and history of SCD care, we came out with very comprehensive summary of where we were and where we want to be,” she said. “The report provides short-, intermediate- and long-term recommendations and identifies which entity and organization should be responsible for implementing them.”

The report authors, led by pediatrician and committee chair Marie Clare McCormick, MD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, stated that about 100,000 people in the United States and millions worldwide live with SCD. The disease kills more than 700 people per year in the United States, and treatment costs an estimated $2 billion a year.

When judged by disability-adjusted life-years lost – a measurement of expected healthy years of life without an illness – the impact of SCD on individuals is estimated to be greater than a long list of other diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, breast cancer, type 1 diabetes, and AIDS/HIV, the report noted.

“The health care needs of individuals living with SCD have been neglected by the U.S. and global health care systems, causing them and their families to suffer,” the report said. “Many of the complications that afflict individuals with SCD, particularly pain, are invisible. Pain is only diagnosed by self-reports, and in SCD there are few to no external indicators of the pain experience. Nevertheless, the pain can be excruciatingly severe and requires treatment with strong analgesics.”

There’s even more misery to the story of SCD, the report said, and Dr. Osunkwo agreed. “It’s not just about pain. These individuals suffer from multiple organ-system complications that are physical but also psychological and societal. They experience a lot of disparities in every aspect of their lives. You’re sick, so then you can’t get a job or health insurance, you can’t get Social Security benefits. You can’t get the type of health care you need nor can you access the other forms of support you need and often you are judged as a drug seeker for complaining of pain or repeatedly seeking acute care for unresolved pain.”

Multiple factors exacerbate the experience of people living with SCD in America, the report said. “Because of systemic racism, unconscious bias, and the stigma associated with the diagnosis, the disease brings with it a much broader burden.”

Dr. Osunkwo put it this way: “SCD is a disease that mostly affects Brown and Black people, and that gets layered into the whole discrimination issues that Black and Brown people face compounding the health burden from their disease.”

The report added that “the SCD community has developed a significant lack of trust in the health care system due to the nearly universal stigma and lack of belief in their reports of pain, a lack of trust that has been further reinforced by historical events, such as the Tuskegee experiment.”

The report highlighted research that finds that Blacks “are more likely to receive a lower quality of pain management than white patients and may be perceived as having drug-seeking behavior.”

The report also identified gaps in treatment, noting that “many SCD complications are not restricted to any one organ system, and the impact of the disease on [quality of life] can be profound but hard to define and compartmentalize.”

Dr. Osunkwo said medical professionals often fail to understand the full breadth of the disease. “There’s no particular look to SCD. When you have cancer, you come in, and you look like you’re sick because you’re bald. Everyone clues into that cancer look and knows it’s lethal, that you’re may likely die early. We don’t have that “look that generates empathy” for SCD, and people don’t understand the burden on those affected. They don’t understand or appreciate that SCD shortens your lifespan as well ... that people living with SCD die 3 decades earlier than their ethnically matched peers. Also, SCD is associated with a lot of pain, and pain and the treatment of pain with opioids makes people [health care providers] uncomfortable unless it’s cancer pain.”

She added: “People also assume that, if it’s not pain, it’s not SCD even though SCD can cause leg ulcers and blood clots and even affect the tonsils, or lead to a stroke. When a disease complexity is too difficult for providers to understand, they either avoid it or don’t do anything for the patient.”

Screening and surveillance for SCD and sickle cell trait is insufficient, the report said, and the potential cost of missed childhood cases is large. Detecting the condition at birth allows the implementation of appropriate comprehensive care and treatment to prevent early death from infections and strokes. As the authors noted, “tremendous strides have been made in the past few decades in the care of children with SCD, which have led to almost all children in high-income settings surviving to adulthood.” However, there remains gaps in care coordination and follow-up of babies screened at birth and even bigger gaps in translating these life span gains to adults particularly around the period of transition from pediatrics to adult care when there appears to be a spike in morbidity and mortality.

The report summarized current treatments for SCD and noted “an influx of pipeline products” after years of little progress and identifies “a need for targeted SCD therapies that address the underlying cause of the disease.”

While treatment recommendations exist, Dr. Osunkwo said, “the evidence for them is very poor and many SCD complications have no evidence-based guidelines for providers to follow. We need more research to provide high quality evidence to make guidelines for SCD treatment stronger and more robust.”

In its final section, the report offers a “strategic plan and blueprint for sickle cell disease action.” It offers several strategies to achieve the vision of “long healthy productive lives for those living with sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait”:

- Establish and fund a research agenda to inform effective programs and policies across the life span.

- Implement efforts to advance understanding of the full impact of sickle cell trait on individuals and society.

- Address barriers to accessing current and pipeline therapies for SCD.

- Improve SCD awareness and strengthen advocacy efforts.

- Increase the number of qualified health professionals providing SCD care.

- Strengthen the evidence base for interventions and disease management and implement widespread efforts to monitor the quality of SCD care.

- Establish organized systems of care assuring both clinical and nonclinical supportive services to all persons living with SCD.

- Establish a national system to collect and link data to characterize the burden of disease, outcomes, and the needs of those with SCD across the life span.

“Right now, the average lifespan for SCD is in the mid-40s to mid-50s,” Dr. Osunkwo said. “That’s a horrible statistic. Even if we just take up half of these recommendations, people will live longer with SCD, and they’ll be more productive and contribute more to society. If we value a cancer life the same as a sickle cell life, we’ll be halfway across the finish line. But the stigma of SCD being a Black and Brown problem is going to be the hardest to confront as it requires a systemic change in our culture as a country and a health care system.”

Still, she said, the commissioning of the report “shows that there is a desire to understand the issue in better detail and try to mitigate it.”

Dr. Osunkwo and Dr. McCormick had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2020.

The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine have just released a 522-page report, but it’s not the usual compilation of guidelines for treatment of a disease. Instead, the authors of “Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action” argue in stark terms that the American society has colossally failed individuals living with sickle cell disease (SCD), who are mostly Black or Brown. A dramatic overhaul of the country’s medical and societal priorities is needed to turn things around to improve health and longevity among this rare disease population.

The findings from the NASEM report are explicit: “There has been substantial success in increasing the survival of children with SCD, but this success had not been translated to similar success as they become adults.” One factor posited to contribute to the slow progress in the improvement of quality and quantity of life for adults living with this disease is the fact that “SCD is largely a disease of African Americans, and as such exists in a context of racial discrimination, health and other societal disparities, mistrust of the health care system, and the effects of poverty.” The report also cites the substantial evidence that those with SCD may receive poorer quality of care.

The report’s 14 authors were made up of an ad hoc committee formed at the request of the Department of Health & Human Services’ Office of Minority Health. The office asked NASEM to convene the committee to develop a strategic plan and blueprint for the United States and others regarding SCD.

The NASEM SCD committee members “realized that we can’t address the medical components of SCD if we don’t explore societal issues and why it’s been so hard to get good care for people with sickle cell disease,” hematologist and report coauthor Ifeyinwa (Ify) Osunkwo, MD, professor of medicine and pediatrics at Atrium Health and director of the Sickle Cell Disease Enterprise, Levine Cancer Institute, Charlotte, N.C., said in an interview. Dr. Osunkwo is also the medical editor of Hematology News.

“After almost a year of meetings and digging into the background and history of SCD care, we came out with very comprehensive summary of where we were and where we want to be,” she said. “The report provides short-, intermediate- and long-term recommendations and identifies which entity and organization should be responsible for implementing them.”

The report authors, led by pediatrician and committee chair Marie Clare McCormick, MD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, stated that about 100,000 people in the United States and millions worldwide live with SCD. The disease kills more than 700 people per year in the United States, and treatment costs an estimated $2 billion a year.

When judged by disability-adjusted life-years lost – a measurement of expected healthy years of life without an illness – the impact of SCD on individuals is estimated to be greater than a long list of other diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, breast cancer, type 1 diabetes, and AIDS/HIV, the report noted.

“The health care needs of individuals living with SCD have been neglected by the U.S. and global health care systems, causing them and their families to suffer,” the report said. “Many of the complications that afflict individuals with SCD, particularly pain, are invisible. Pain is only diagnosed by self-reports, and in SCD there are few to no external indicators of the pain experience. Nevertheless, the pain can be excruciatingly severe and requires treatment with strong analgesics.”

There’s even more misery to the story of SCD, the report said, and Dr. Osunkwo agreed. “It’s not just about pain. These individuals suffer from multiple organ-system complications that are physical but also psychological and societal. They experience a lot of disparities in every aspect of their lives. You’re sick, so then you can’t get a job or health insurance, you can’t get Social Security benefits. You can’t get the type of health care you need nor can you access the other forms of support you need and often you are judged as a drug seeker for complaining of pain or repeatedly seeking acute care for unresolved pain.”

Multiple factors exacerbate the experience of people living with SCD in America, the report said. “Because of systemic racism, unconscious bias, and the stigma associated with the diagnosis, the disease brings with it a much broader burden.”

Dr. Osunkwo put it this way: “SCD is a disease that mostly affects Brown and Black people, and that gets layered into the whole discrimination issues that Black and Brown people face compounding the health burden from their disease.”

The report added that “the SCD community has developed a significant lack of trust in the health care system due to the nearly universal stigma and lack of belief in their reports of pain, a lack of trust that has been further reinforced by historical events, such as the Tuskegee experiment.”

The report highlighted research that finds that Blacks “are more likely to receive a lower quality of pain management than white patients and may be perceived as having drug-seeking behavior.”

The report also identified gaps in treatment, noting that “many SCD complications are not restricted to any one organ system, and the impact of the disease on [quality of life] can be profound but hard to define and compartmentalize.”

Dr. Osunkwo said medical professionals often fail to understand the full breadth of the disease. “There’s no particular look to SCD. When you have cancer, you come in, and you look like you’re sick because you’re bald. Everyone clues into that cancer look and knows it’s lethal, that you’re may likely die early. We don’t have that “look that generates empathy” for SCD, and people don’t understand the burden on those affected. They don’t understand or appreciate that SCD shortens your lifespan as well ... that people living with SCD die 3 decades earlier than their ethnically matched peers. Also, SCD is associated with a lot of pain, and pain and the treatment of pain with opioids makes people [health care providers] uncomfortable unless it’s cancer pain.”

She added: “People also assume that, if it’s not pain, it’s not SCD even though SCD can cause leg ulcers and blood clots and even affect the tonsils, or lead to a stroke. When a disease complexity is too difficult for providers to understand, they either avoid it or don’t do anything for the patient.”

Screening and surveillance for SCD and sickle cell trait is insufficient, the report said, and the potential cost of missed childhood cases is large. Detecting the condition at birth allows the implementation of appropriate comprehensive care and treatment to prevent early death from infections and strokes. As the authors noted, “tremendous strides have been made in the past few decades in the care of children with SCD, which have led to almost all children in high-income settings surviving to adulthood.” However, there remains gaps in care coordination and follow-up of babies screened at birth and even bigger gaps in translating these life span gains to adults particularly around the period of transition from pediatrics to adult care when there appears to be a spike in morbidity and mortality.

The report summarized current treatments for SCD and noted “an influx of pipeline products” after years of little progress and identifies “a need for targeted SCD therapies that address the underlying cause of the disease.”

While treatment recommendations exist, Dr. Osunkwo said, “the evidence for them is very poor and many SCD complications have no evidence-based guidelines for providers to follow. We need more research to provide high quality evidence to make guidelines for SCD treatment stronger and more robust.”

In its final section, the report offers a “strategic plan and blueprint for sickle cell disease action.” It offers several strategies to achieve the vision of “long healthy productive lives for those living with sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait”:

- Establish and fund a research agenda to inform effective programs and policies across the life span.

- Implement efforts to advance understanding of the full impact of sickle cell trait on individuals and society.

- Address barriers to accessing current and pipeline therapies for SCD.

- Improve SCD awareness and strengthen advocacy efforts.

- Increase the number of qualified health professionals providing SCD care.

- Strengthen the evidence base for interventions and disease management and implement widespread efforts to monitor the quality of SCD care.

- Establish organized systems of care assuring both clinical and nonclinical supportive services to all persons living with SCD.

- Establish a national system to collect and link data to characterize the burden of disease, outcomes, and the needs of those with SCD across the life span.

“Right now, the average lifespan for SCD is in the mid-40s to mid-50s,” Dr. Osunkwo said. “That’s a horrible statistic. Even if we just take up half of these recommendations, people will live longer with SCD, and they’ll be more productive and contribute more to society. If we value a cancer life the same as a sickle cell life, we’ll be halfway across the finish line. But the stigma of SCD being a Black and Brown problem is going to be the hardest to confront as it requires a systemic change in our culture as a country and a health care system.”

Still, she said, the commissioning of the report “shows that there is a desire to understand the issue in better detail and try to mitigate it.”

Dr. Osunkwo and Dr. McCormick had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2020.

The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine have just released a 522-page report, but it’s not the usual compilation of guidelines for treatment of a disease. Instead, the authors of “Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action” argue in stark terms that the American society has colossally failed individuals living with sickle cell disease (SCD), who are mostly Black or Brown. A dramatic overhaul of the country’s medical and societal priorities is needed to turn things around to improve health and longevity among this rare disease population.

The findings from the NASEM report are explicit: “There has been substantial success in increasing the survival of children with SCD, but this success had not been translated to similar success as they become adults.” One factor posited to contribute to the slow progress in the improvement of quality and quantity of life for adults living with this disease is the fact that “SCD is largely a disease of African Americans, and as such exists in a context of racial discrimination, health and other societal disparities, mistrust of the health care system, and the effects of poverty.” The report also cites the substantial evidence that those with SCD may receive poorer quality of care.

The report’s 14 authors were made up of an ad hoc committee formed at the request of the Department of Health & Human Services’ Office of Minority Health. The office asked NASEM to convene the committee to develop a strategic plan and blueprint for the United States and others regarding SCD.

The NASEM SCD committee members “realized that we can’t address the medical components of SCD if we don’t explore societal issues and why it’s been so hard to get good care for people with sickle cell disease,” hematologist and report coauthor Ifeyinwa (Ify) Osunkwo, MD, professor of medicine and pediatrics at Atrium Health and director of the Sickle Cell Disease Enterprise, Levine Cancer Institute, Charlotte, N.C., said in an interview. Dr. Osunkwo is also the medical editor of Hematology News.

“After almost a year of meetings and digging into the background and history of SCD care, we came out with very comprehensive summary of where we were and where we want to be,” she said. “The report provides short-, intermediate- and long-term recommendations and identifies which entity and organization should be responsible for implementing them.”

The report authors, led by pediatrician and committee chair Marie Clare McCormick, MD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, stated that about 100,000 people in the United States and millions worldwide live with SCD. The disease kills more than 700 people per year in the United States, and treatment costs an estimated $2 billion a year.

When judged by disability-adjusted life-years lost – a measurement of expected healthy years of life without an illness – the impact of SCD on individuals is estimated to be greater than a long list of other diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, breast cancer, type 1 diabetes, and AIDS/HIV, the report noted.

“The health care needs of individuals living with SCD have been neglected by the U.S. and global health care systems, causing them and their families to suffer,” the report said. “Many of the complications that afflict individuals with SCD, particularly pain, are invisible. Pain is only diagnosed by self-reports, and in SCD there are few to no external indicators of the pain experience. Nevertheless, the pain can be excruciatingly severe and requires treatment with strong analgesics.”

There’s even more misery to the story of SCD, the report said, and Dr. Osunkwo agreed. “It’s not just about pain. These individuals suffer from multiple organ-system complications that are physical but also psychological and societal. They experience a lot of disparities in every aspect of their lives. You’re sick, so then you can’t get a job or health insurance, you can’t get Social Security benefits. You can’t get the type of health care you need nor can you access the other forms of support you need and often you are judged as a drug seeker for complaining of pain or repeatedly seeking acute care for unresolved pain.”

Multiple factors exacerbate the experience of people living with SCD in America, the report said. “Because of systemic racism, unconscious bias, and the stigma associated with the diagnosis, the disease brings with it a much broader burden.”

Dr. Osunkwo put it this way: “SCD is a disease that mostly affects Brown and Black people, and that gets layered into the whole discrimination issues that Black and Brown people face compounding the health burden from their disease.”

The report added that “the SCD community has developed a significant lack of trust in the health care system due to the nearly universal stigma and lack of belief in their reports of pain, a lack of trust that has been further reinforced by historical events, such as the Tuskegee experiment.”

The report highlighted research that finds that Blacks “are more likely to receive a lower quality of pain management than white patients and may be perceived as having drug-seeking behavior.”

The report also identified gaps in treatment, noting that “many SCD complications are not restricted to any one organ system, and the impact of the disease on [quality of life] can be profound but hard to define and compartmentalize.”

Dr. Osunkwo said medical professionals often fail to understand the full breadth of the disease. “There’s no particular look to SCD. When you have cancer, you come in, and you look like you’re sick because you’re bald. Everyone clues into that cancer look and knows it’s lethal, that you’re may likely die early. We don’t have that “look that generates empathy” for SCD, and people don’t understand the burden on those affected. They don’t understand or appreciate that SCD shortens your lifespan as well ... that people living with SCD die 3 decades earlier than their ethnically matched peers. Also, SCD is associated with a lot of pain, and pain and the treatment of pain with opioids makes people [health care providers] uncomfortable unless it’s cancer pain.”

She added: “People also assume that, if it’s not pain, it’s not SCD even though SCD can cause leg ulcers and blood clots and even affect the tonsils, or lead to a stroke. When a disease complexity is too difficult for providers to understand, they either avoid it or don’t do anything for the patient.”

Screening and surveillance for SCD and sickle cell trait is insufficient, the report said, and the potential cost of missed childhood cases is large. Detecting the condition at birth allows the implementation of appropriate comprehensive care and treatment to prevent early death from infections and strokes. As the authors noted, “tremendous strides have been made in the past few decades in the care of children with SCD, which have led to almost all children in high-income settings surviving to adulthood.” However, there remains gaps in care coordination and follow-up of babies screened at birth and even bigger gaps in translating these life span gains to adults particularly around the period of transition from pediatrics to adult care when there appears to be a spike in morbidity and mortality.

The report summarized current treatments for SCD and noted “an influx of pipeline products” after years of little progress and identifies “a need for targeted SCD therapies that address the underlying cause of the disease.”

While treatment recommendations exist, Dr. Osunkwo said, “the evidence for them is very poor and many SCD complications have no evidence-based guidelines for providers to follow. We need more research to provide high quality evidence to make guidelines for SCD treatment stronger and more robust.”

In its final section, the report offers a “strategic plan and blueprint for sickle cell disease action.” It offers several strategies to achieve the vision of “long healthy productive lives for those living with sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait”:

- Establish and fund a research agenda to inform effective programs and policies across the life span.

- Implement efforts to advance understanding of the full impact of sickle cell trait on individuals and society.

- Address barriers to accessing current and pipeline therapies for SCD.

- Improve SCD awareness and strengthen advocacy efforts.

- Increase the number of qualified health professionals providing SCD care.

- Strengthen the evidence base for interventions and disease management and implement widespread efforts to monitor the quality of SCD care.

- Establish organized systems of care assuring both clinical and nonclinical supportive services to all persons living with SCD.

- Establish a national system to collect and link data to characterize the burden of disease, outcomes, and the needs of those with SCD across the life span.

“Right now, the average lifespan for SCD is in the mid-40s to mid-50s,” Dr. Osunkwo said. “That’s a horrible statistic. Even if we just take up half of these recommendations, people will live longer with SCD, and they’ll be more productive and contribute more to society. If we value a cancer life the same as a sickle cell life, we’ll be halfway across the finish line. But the stigma of SCD being a Black and Brown problem is going to be the hardest to confront as it requires a systemic change in our culture as a country and a health care system.”

Still, she said, the commissioning of the report “shows that there is a desire to understand the issue in better detail and try to mitigate it.”

Dr. Osunkwo and Dr. McCormick had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Addressing Sickle Cell Disease: A Strategic Plan and Blueprint for Action. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2020.