User login

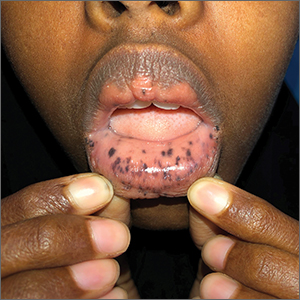

This patient was given a diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) based on the characteristic pigmented mucocutaneous macules and numerous polyps in her stomach and small bowel. PJS is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation, polyposis of the GI tract, and increased cancer risk. The prevalence is approximately 1 in 100,000.1 Genetic testing for the STK11 gene mutation, which is found in 70% of familial cases and 30% to 67% of sporadic cases, is not required for diagnosis.1

The bluish brown to black spots of PJS often are apparent at birth or in early infancy. They are most common on the lips, buccal mucosa, perioral region, palms, and soles.

The polyps may cause bleeding, anemia, and abdominal pain due to intussusception, obstruction, or infarction.2 Polyps usually are benign, but patients are at increased risk of GI and non-GI malignancies such as breast, pancreas, lung, and reproductive tract cancers.1

PJS can be differentiated from other causes of hyperpigmentation by clinical presentation and/or genetic testing. The diagnosis of PJS is made using the following criteria: (1) two or more histologically confirmed PJS polyps, (2) any number of PJS polyps and a family history of PJS, (3) characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation and a family history of PJS, or (4) any number of PJS polyps and characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation.2

It’s recommended that polyps be removed when technically feasible.3 Pigmented macules do not require treatment. Macules on the lips may disappear with time, while those on the buccal mucosa persist. The lip lesions can be lightened with chemical peels or laser.

This patient underwent laparotomy, which revealed a grossly dilated and gangrenous small bowel segment. Intussusception was not present and was thought to have spontaneously reduced. Resection and anastomosis of the affected small bowel was performed. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and her diarrhea and abdominal pain resolved. A colonoscopy was normal, and the health care team explained that she would require follow-up and surveillance of her condition due to the high risk of future cancers.

This case was adapted from: Warsame MO, McMichael JR. Chronic abdominal pain and diarrhea. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:365,366,368.

Photos courtesy of Mohamed Omar Warsame, MBBS, and Josette R. McMichael, MD

1. Kopacova M, Tacheci I, Rejchrt S, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5397-5408.

2. Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986.

3. van Lier MG, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Wagner A, et al. High cumulative risk of intussusception in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: time to update surveillance guidelines? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:940-945.

This patient was given a diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) based on the characteristic pigmented mucocutaneous macules and numerous polyps in her stomach and small bowel. PJS is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation, polyposis of the GI tract, and increased cancer risk. The prevalence is approximately 1 in 100,000.1 Genetic testing for the STK11 gene mutation, which is found in 70% of familial cases and 30% to 67% of sporadic cases, is not required for diagnosis.1

The bluish brown to black spots of PJS often are apparent at birth or in early infancy. They are most common on the lips, buccal mucosa, perioral region, palms, and soles.

The polyps may cause bleeding, anemia, and abdominal pain due to intussusception, obstruction, or infarction.2 Polyps usually are benign, but patients are at increased risk of GI and non-GI malignancies such as breast, pancreas, lung, and reproductive tract cancers.1

PJS can be differentiated from other causes of hyperpigmentation by clinical presentation and/or genetic testing. The diagnosis of PJS is made using the following criteria: (1) two or more histologically confirmed PJS polyps, (2) any number of PJS polyps and a family history of PJS, (3) characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation and a family history of PJS, or (4) any number of PJS polyps and characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation.2

It’s recommended that polyps be removed when technically feasible.3 Pigmented macules do not require treatment. Macules on the lips may disappear with time, while those on the buccal mucosa persist. The lip lesions can be lightened with chemical peels or laser.

This patient underwent laparotomy, which revealed a grossly dilated and gangrenous small bowel segment. Intussusception was not present and was thought to have spontaneously reduced. Resection and anastomosis of the affected small bowel was performed. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and her diarrhea and abdominal pain resolved. A colonoscopy was normal, and the health care team explained that she would require follow-up and surveillance of her condition due to the high risk of future cancers.

This case was adapted from: Warsame MO, McMichael JR. Chronic abdominal pain and diarrhea. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:365,366,368.

Photos courtesy of Mohamed Omar Warsame, MBBS, and Josette R. McMichael, MD

This patient was given a diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) based on the characteristic pigmented mucocutaneous macules and numerous polyps in her stomach and small bowel. PJS is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation, polyposis of the GI tract, and increased cancer risk. The prevalence is approximately 1 in 100,000.1 Genetic testing for the STK11 gene mutation, which is found in 70% of familial cases and 30% to 67% of sporadic cases, is not required for diagnosis.1

The bluish brown to black spots of PJS often are apparent at birth or in early infancy. They are most common on the lips, buccal mucosa, perioral region, palms, and soles.

The polyps may cause bleeding, anemia, and abdominal pain due to intussusception, obstruction, or infarction.2 Polyps usually are benign, but patients are at increased risk of GI and non-GI malignancies such as breast, pancreas, lung, and reproductive tract cancers.1

PJS can be differentiated from other causes of hyperpigmentation by clinical presentation and/or genetic testing. The diagnosis of PJS is made using the following criteria: (1) two or more histologically confirmed PJS polyps, (2) any number of PJS polyps and a family history of PJS, (3) characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation and a family history of PJS, or (4) any number of PJS polyps and characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation.2

It’s recommended that polyps be removed when technically feasible.3 Pigmented macules do not require treatment. Macules on the lips may disappear with time, while those on the buccal mucosa persist. The lip lesions can be lightened with chemical peels or laser.

This patient underwent laparotomy, which revealed a grossly dilated and gangrenous small bowel segment. Intussusception was not present and was thought to have spontaneously reduced. Resection and anastomosis of the affected small bowel was performed. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and her diarrhea and abdominal pain resolved. A colonoscopy was normal, and the health care team explained that she would require follow-up and surveillance of her condition due to the high risk of future cancers.

This case was adapted from: Warsame MO, McMichael JR. Chronic abdominal pain and diarrhea. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:365,366,368.

Photos courtesy of Mohamed Omar Warsame, MBBS, and Josette R. McMichael, MD

1. Kopacova M, Tacheci I, Rejchrt S, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5397-5408.

2. Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986.

3. van Lier MG, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Wagner A, et al. High cumulative risk of intussusception in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: time to update surveillance guidelines? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:940-945.

1. Kopacova M, Tacheci I, Rejchrt S, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5397-5408.

2. Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986.

3. van Lier MG, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Wagner A, et al. High cumulative risk of intussusception in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: time to update surveillance guidelines? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:940-945.