User login

CASE Pregnant woman with herpes simplex virus

A 26-year-old primigravid woman at 12 weeks of gestation indicates that she had an initial episode of herpes simplex virus (HSV) 6 years prior to presentation. Subsequently, she has had 1 to 2 recurrent episodes each year. She asks about the implications of HSV infection in pregnancy, particularly if anything can be done to prevent a recurrent outbreak near her due date and reduce the need for a cesarean delivery.

How would you counsel this patient?

Meet our perpetrator

Herpes simplex virus (HSV), the most prevalent sexually transmitted infection, is a DNA virus that has 2 major strains: HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-1 frequently is acquired in early childhood through nonsexual contact and typically causes orolabial and, less commonly, genital outbreaks. HSV-2 is almost always acquired through sexual contact and causes mainly genital outbreaks.1

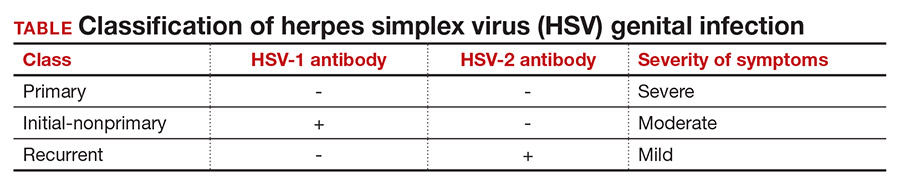

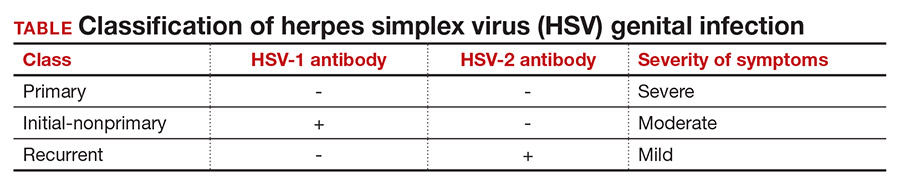

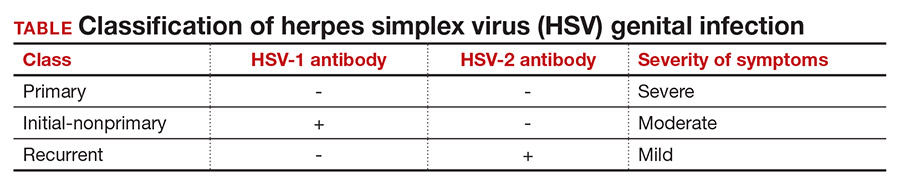

There are 3 classifications of HSV infection: primary, initial-nonprimary, and recurrent (TABLE).

Primary infection refers to infection in a person without antibodies to either type of HSV.

Initial-nonprimary infection refers to acquisition of HSV-2 in a patient with preexisting antibodies to HSV-1 or vice versa. Patients tend to have more severe symptoms with primary as opposed to initial-nonprimary infection because, with the latter condition, preexisting antibodies provide partial protection against the opposing HSV type.1 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the seroprevalence of HSV-1 has decreased by approximately 23% in adolescents aged 14 to 19 years, with a resultant increase in the number of primary HSV-1 genital infections through oral-sexual contact in adulthood.2

Recurrent infection refers to reactivation of the same HSV type corresponding to the serum antibodies.

Clinical presentation

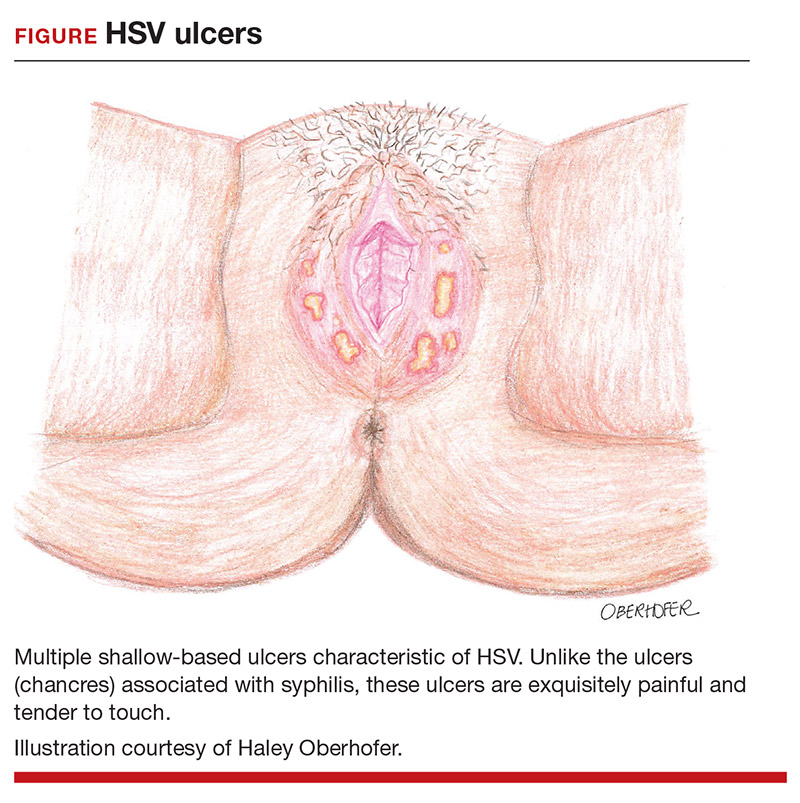

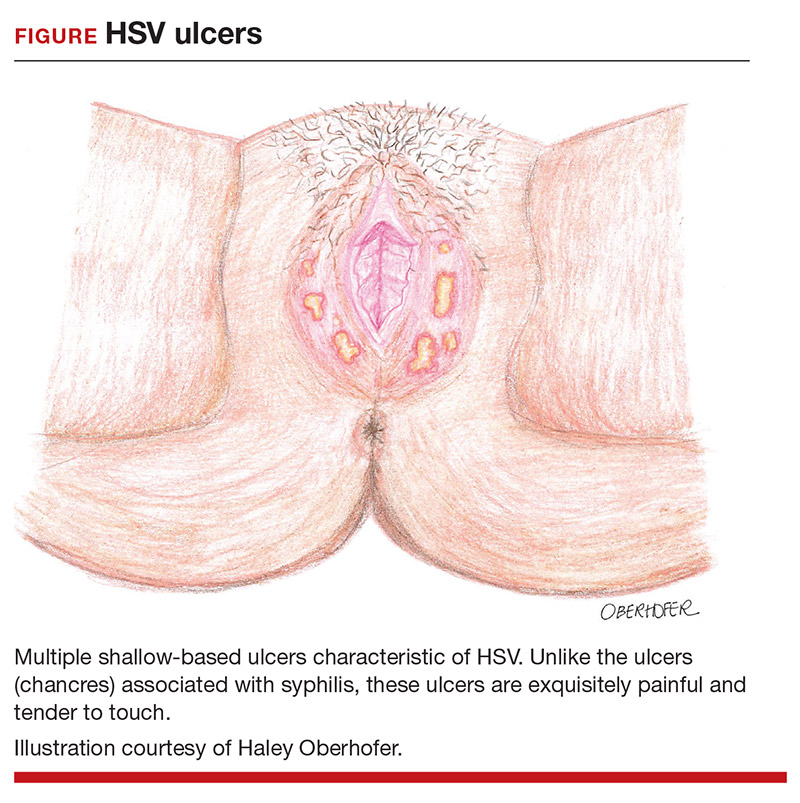

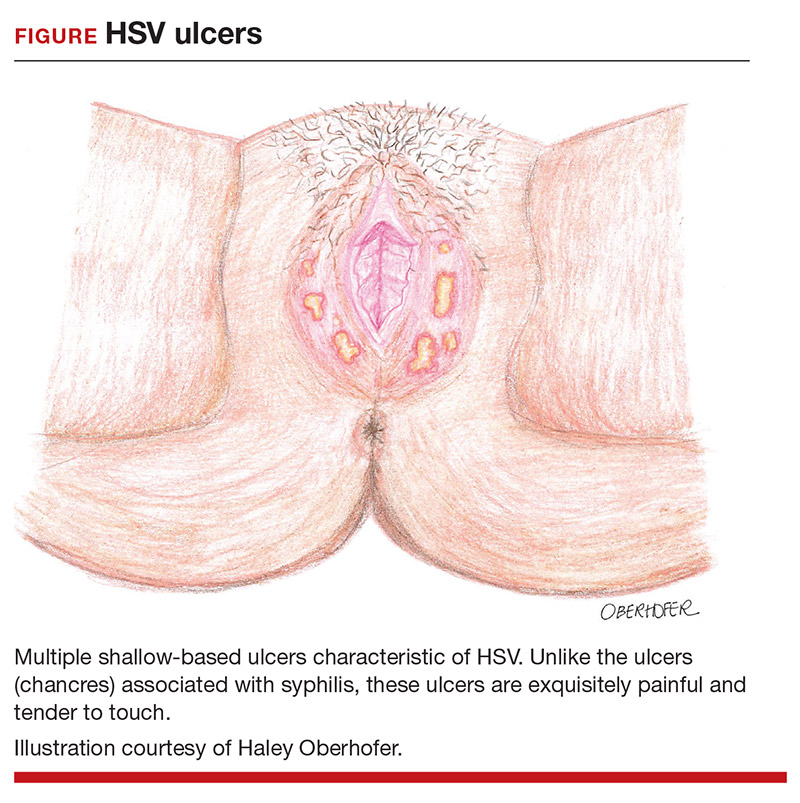

After an incubation period of 4 to 7 days, symptomatic patients with primary and initial-nonprimary genital HSV infections typically present with multiple, bilateral genital lesions at various stages of development. These lesions begin as small erythematous macules and then progress to papules, vesicles, pustules, ulcers, and crusted scabs over a period of 3 to 6 weeks1 (FIGURE). Patients also may present with fever, headache, fatigue, dysuria, and painful inguinal lymphadenopathy. Patients with recurrent infections usually experience prodromal itching or tingling for 2 to 5 days prior to the appearance of unilateral lesions, which persist for only 5 to 10 days. Systemic symptoms rarely are present. HSV-1 genital infection has a symptomatic recurrence rate of 20% to 50% within the first year, while HSV-2 has a recurrence rate of 70% to 90%.1

The majority of primary and initial-nonprimary infections are subclinical. One study showed that 74% of HSV-1 and 63% of HSV-2 initial genital herpes infections were asymptomatic.3 The relevance of this observation is that patients may not present for evaluation unless they experience a symptomatic recurrent infection. Meanwhile, they are asymptomatically shedding the virus and unknowingly transmitting HSV to their sexual partners. Asymptomatic viral shedding is more common with HSV-2 and is the most common source of transmission.4 The rate of asymptomatic shedding is unpredictable and has been shown to occur on 10% to 20% of days.1

Diagnosis and treatment

The gold standard for diagnosing HSV infection is viral culture; however, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays are faster to result and more sensitive.4,5 Both culture and PCR studies can distinguish the HSV type, allowing physicians to counsel patients regarding the expected clinical course, rate of recurrence, and implications for future pregnancies. After an initial infection, it may take up to 12 weeks for patients to develop detectable antibodies. Therefore, serology can be quite useful in determining the timing and classification of the infection. For example, a patient with HSV-2 isolated on viral culture or PCR and HSV-1 antibodies identified on serology is classified as having an initial-nonprimary infection.4

HSV treatment is dependent on the classification of infection. Treatment of primary and initial-nonprimary infection includes:

- acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily

- valacyclovir 1,000 mg orally twice daily, or

- famciclovir 250 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 to 10 days.

Ideally, treatment should be initiated within 72 hours of symptom onset.

Recurrent infections may be treated with:

- acyclovir 400 mg orally three times daily for 5 days

- valacyclovir 1,000 mg orally once daily for 5 days, or

- famciclovir 1,000 mg orally every 12 hours for 2 doses.

Ideally, treatment should begin within 24 hours of symptom onset.4,6

Patients with immunocompromising conditions, severe/frequent outbreaks (>6 per year), or who desire to reduce the risk of transmission to HSV-uninfected partners are candidates for chronic suppressive therapy. Suppressive options include acyclovir 400 mg orally twice daily, valacyclovir 500 mg orally once daily, and famciclovir 250 mg orally twice daily. Of note, there are many regimens available for acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir; all have similar efficacy in decreasing symptom severity, time to lesion healing, and duration of viral shedding.6 Acyclovir generally is the least expensive option.4

Continue to: Pregnancy and prevention...

Pregnancy and prevention

During pregnancy, 2% of women will acquire HSV, and 70% of these women will be asymptomatic.4,7 Approximately one-third to one-half of neonatal infections are caused by HSV-1.8 The most devastating complication of HSV infection in pregnancy is transmission to the newborn. Neonatal herpes is defined as the diagnosis of an HSV infection in a neonate within the first 28 days of life. The disease spectrum varies widely, and early recognition and treatment can substantially reduce the degree of morbidity and mortality associated with systemic infections.

HSV infection limited to the skin, eyes, and mucosal surfaces accounts for 45% of neonatal infections. When this condition is promptly recognized, neonates typically respond well to intravenous acyclovir, with prevention of systemic progression and overall good clinical outcomes. Infections of the central nervous system account for 30% of infections and are more difficult to diagnose due to the nonspecific symptomatology, including lethargy, poor feeding, seizures, and possible absence of lesions. The risk for death decreases from 50% to 6% with treatment; however, most neonates will still require close long-term surveillance for achievement of neurodevelopmental milestones and frequent ophthalmologic and hearing assessments.8,9 Disseminated HSV accounts for 25% of infections and can cause multiorgan failure, with a 31% risk for death despite treatment.5 Therefore, the cornerstone of managing HSV infection in pregnancy is focusing clinical efforts on prevention of transmission to the neonate.

More than 90% of neonatal herpes infections are acquired intrapartum,4 with 60% to 80% of cases occurring in women who developed HSV in the third trimester near the time of delivery.5 Neonates delivered vaginally to these women have a 30% to 50% risk of infection, compared to a <1% risk in neonates born to women with recurrent HSV.1,5,10 The discrepancy in infection risk is thought to be secondary to higher HSV viral loads after an initial infection as opposed to a recurrent infection. Furthermore, acquisition of HSV near term does not allow for the 6 to 12 weeks necessary to develop antibodies that can cross the placenta and provide neonatal protection. The risk of vertical transmission is approximately 25% with an initial-nonprimary episode, reflecting the partial protection afforded by antibody against the other viral serotype.11

Prophylactic therapy has been shown to reduce the rate of asymptomatic viral shedding and recurrent infections near term.7 To reduce the risk of intrapartum transmission, women with a history of HSV prior to or during pregnancy should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily starting at 36 weeks of gestation. When patients present with rupture of membranes or labor, they should be asked about prodromal symptoms and thoroughly examined. If prodromal symptoms are present or genital lesions identified, patients should undergo cesarean delivery.12 Some experts also recommend cesarean delivery for women who acquire primary or initial-nonprimary HSV infection in the third trimester due to higher viral loads and potential lack of antibodies at the time of delivery.8,12 However, this recommendation has not been validated by a rigorous prospective randomized clinical trial. When clinically feasible, avoidance of invasive fetal monitoring during labor also has been shown to decrease the risk of HSV transmission by approximately 84% in women with asymptomatic viral shedding.12 This concept may be extrapolated to include assisted delivery with vacuum or forceps.

Universal screening for HSV infection in pregnancy is controversial and widely debated. Most HSV seropositive patients are asymptomatic and will not report a history of HSV infection at the initial prenatal visit. Universal screening, therefore, may increase the rate of unnecessary cesarean deliveries and medical interventions. HSV serology may be beneficial, however, in identifying seronegative pregnant women who have seropositive partners. Two recent studies have shown that 15% to 25% of couples have discordant HSV serologies and consequently are at risk of acquiring primary or initial-nonprimary HSV near term.4,5 These couples should be counseled concerning the use of condoms in the first and second trimester (50% reduction in HSV transmission) and abstinence in the third trimester.5 The seropositive partner also can be offered suppressive therapy, which provides a 48% reduction in the risk of HSV transmission.4 Ultimately, the difficulty lies in balancing the clinical benefits and cost of asymptomatic screening.11

CASE Resolved

The patient should be counseled that HSV infection rarely affects the fetus in utero, and transmission almost always occurs during the delivery process. This patient should receive prophylactic treatment with acyclovir beginning at 36 weeks of gestation to reduce the risk of an outbreak near the time of delivery. ●

- Gnann JW, Whitley RJ. Genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:666-674.

- Bradley H, Markowitz LE, Gibson T, et al. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 — United States, 1999–2010. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:325-333.

- Bernstein DI, Bellamy AR, Hook EW, et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and antibody response to primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in young women. Clin Infec Dis. 2012;56:344-351.

- Brown ZA, Gardella C, Wald A, et al. Genital herpes complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:426-437.

- Corey L, Wald A. Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1376-1385.

- Albrecht MA. Treatment of genital herpes simplex virus infection. UpToDate website. Updated June 4, 2019. Accessed March 21, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-genital-herpes-simplex-virus-infection?search=hsv+treatment

- Sheffield J, Wendel G Jr, Stuart G, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis to prevent herpes simplex virus recurrence at delivery: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1396-1403.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of genital herpes in pregnancy: ACOG practice bulletin summary, number 220. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:1236-1238.

- Kimberlin DW. Oral acyclovir suppression after neonatal herpes. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1284-1292.

- Brown ZA, Benedetti J, Ashley R, et al. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection in relation to asymptomatic maternal infection at the time of labor. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1247-1252.

- Chatroux IC, Hersh AR, Caughey AB. Herpes simplex virus serotyping in pregnant women with a history of genital herpes and an outbreak in the third trimester. a cost effectiveness analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:63-71.

- Brown ZA, Wald A, Morrow RA, et al. Effect of serologic status and cesarean delivery on transmission rates of herpes simplex virus from mother to infant. JAMA. 2003;289:203-209.

CASE Pregnant woman with herpes simplex virus

A 26-year-old primigravid woman at 12 weeks of gestation indicates that she had an initial episode of herpes simplex virus (HSV) 6 years prior to presentation. Subsequently, she has had 1 to 2 recurrent episodes each year. She asks about the implications of HSV infection in pregnancy, particularly if anything can be done to prevent a recurrent outbreak near her due date and reduce the need for a cesarean delivery.

How would you counsel this patient?

Meet our perpetrator

Herpes simplex virus (HSV), the most prevalent sexually transmitted infection, is a DNA virus that has 2 major strains: HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-1 frequently is acquired in early childhood through nonsexual contact and typically causes orolabial and, less commonly, genital outbreaks. HSV-2 is almost always acquired through sexual contact and causes mainly genital outbreaks.1

There are 3 classifications of HSV infection: primary, initial-nonprimary, and recurrent (TABLE).

Primary infection refers to infection in a person without antibodies to either type of HSV.

Initial-nonprimary infection refers to acquisition of HSV-2 in a patient with preexisting antibodies to HSV-1 or vice versa. Patients tend to have more severe symptoms with primary as opposed to initial-nonprimary infection because, with the latter condition, preexisting antibodies provide partial protection against the opposing HSV type.1 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the seroprevalence of HSV-1 has decreased by approximately 23% in adolescents aged 14 to 19 years, with a resultant increase in the number of primary HSV-1 genital infections through oral-sexual contact in adulthood.2

Recurrent infection refers to reactivation of the same HSV type corresponding to the serum antibodies.

Clinical presentation

After an incubation period of 4 to 7 days, symptomatic patients with primary and initial-nonprimary genital HSV infections typically present with multiple, bilateral genital lesions at various stages of development. These lesions begin as small erythematous macules and then progress to papules, vesicles, pustules, ulcers, and crusted scabs over a period of 3 to 6 weeks1 (FIGURE). Patients also may present with fever, headache, fatigue, dysuria, and painful inguinal lymphadenopathy. Patients with recurrent infections usually experience prodromal itching or tingling for 2 to 5 days prior to the appearance of unilateral lesions, which persist for only 5 to 10 days. Systemic symptoms rarely are present. HSV-1 genital infection has a symptomatic recurrence rate of 20% to 50% within the first year, while HSV-2 has a recurrence rate of 70% to 90%.1

The majority of primary and initial-nonprimary infections are subclinical. One study showed that 74% of HSV-1 and 63% of HSV-2 initial genital herpes infections were asymptomatic.3 The relevance of this observation is that patients may not present for evaluation unless they experience a symptomatic recurrent infection. Meanwhile, they are asymptomatically shedding the virus and unknowingly transmitting HSV to their sexual partners. Asymptomatic viral shedding is more common with HSV-2 and is the most common source of transmission.4 The rate of asymptomatic shedding is unpredictable and has been shown to occur on 10% to 20% of days.1

Diagnosis and treatment

The gold standard for diagnosing HSV infection is viral culture; however, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays are faster to result and more sensitive.4,5 Both culture and PCR studies can distinguish the HSV type, allowing physicians to counsel patients regarding the expected clinical course, rate of recurrence, and implications for future pregnancies. After an initial infection, it may take up to 12 weeks for patients to develop detectable antibodies. Therefore, serology can be quite useful in determining the timing and classification of the infection. For example, a patient with HSV-2 isolated on viral culture or PCR and HSV-1 antibodies identified on serology is classified as having an initial-nonprimary infection.4

HSV treatment is dependent on the classification of infection. Treatment of primary and initial-nonprimary infection includes:

- acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily

- valacyclovir 1,000 mg orally twice daily, or

- famciclovir 250 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 to 10 days.

Ideally, treatment should be initiated within 72 hours of symptom onset.

Recurrent infections may be treated with:

- acyclovir 400 mg orally three times daily for 5 days

- valacyclovir 1,000 mg orally once daily for 5 days, or

- famciclovir 1,000 mg orally every 12 hours for 2 doses.

Ideally, treatment should begin within 24 hours of symptom onset.4,6

Patients with immunocompromising conditions, severe/frequent outbreaks (>6 per year), or who desire to reduce the risk of transmission to HSV-uninfected partners are candidates for chronic suppressive therapy. Suppressive options include acyclovir 400 mg orally twice daily, valacyclovir 500 mg orally once daily, and famciclovir 250 mg orally twice daily. Of note, there are many regimens available for acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir; all have similar efficacy in decreasing symptom severity, time to lesion healing, and duration of viral shedding.6 Acyclovir generally is the least expensive option.4

Continue to: Pregnancy and prevention...

Pregnancy and prevention

During pregnancy, 2% of women will acquire HSV, and 70% of these women will be asymptomatic.4,7 Approximately one-third to one-half of neonatal infections are caused by HSV-1.8 The most devastating complication of HSV infection in pregnancy is transmission to the newborn. Neonatal herpes is defined as the diagnosis of an HSV infection in a neonate within the first 28 days of life. The disease spectrum varies widely, and early recognition and treatment can substantially reduce the degree of morbidity and mortality associated with systemic infections.

HSV infection limited to the skin, eyes, and mucosal surfaces accounts for 45% of neonatal infections. When this condition is promptly recognized, neonates typically respond well to intravenous acyclovir, with prevention of systemic progression and overall good clinical outcomes. Infections of the central nervous system account for 30% of infections and are more difficult to diagnose due to the nonspecific symptomatology, including lethargy, poor feeding, seizures, and possible absence of lesions. The risk for death decreases from 50% to 6% with treatment; however, most neonates will still require close long-term surveillance for achievement of neurodevelopmental milestones and frequent ophthalmologic and hearing assessments.8,9 Disseminated HSV accounts for 25% of infections and can cause multiorgan failure, with a 31% risk for death despite treatment.5 Therefore, the cornerstone of managing HSV infection in pregnancy is focusing clinical efforts on prevention of transmission to the neonate.

More than 90% of neonatal herpes infections are acquired intrapartum,4 with 60% to 80% of cases occurring in women who developed HSV in the third trimester near the time of delivery.5 Neonates delivered vaginally to these women have a 30% to 50% risk of infection, compared to a <1% risk in neonates born to women with recurrent HSV.1,5,10 The discrepancy in infection risk is thought to be secondary to higher HSV viral loads after an initial infection as opposed to a recurrent infection. Furthermore, acquisition of HSV near term does not allow for the 6 to 12 weeks necessary to develop antibodies that can cross the placenta and provide neonatal protection. The risk of vertical transmission is approximately 25% with an initial-nonprimary episode, reflecting the partial protection afforded by antibody against the other viral serotype.11

Prophylactic therapy has been shown to reduce the rate of asymptomatic viral shedding and recurrent infections near term.7 To reduce the risk of intrapartum transmission, women with a history of HSV prior to or during pregnancy should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily starting at 36 weeks of gestation. When patients present with rupture of membranes or labor, they should be asked about prodromal symptoms and thoroughly examined. If prodromal symptoms are present or genital lesions identified, patients should undergo cesarean delivery.12 Some experts also recommend cesarean delivery for women who acquire primary or initial-nonprimary HSV infection in the third trimester due to higher viral loads and potential lack of antibodies at the time of delivery.8,12 However, this recommendation has not been validated by a rigorous prospective randomized clinical trial. When clinically feasible, avoidance of invasive fetal monitoring during labor also has been shown to decrease the risk of HSV transmission by approximately 84% in women with asymptomatic viral shedding.12 This concept may be extrapolated to include assisted delivery with vacuum or forceps.

Universal screening for HSV infection in pregnancy is controversial and widely debated. Most HSV seropositive patients are asymptomatic and will not report a history of HSV infection at the initial prenatal visit. Universal screening, therefore, may increase the rate of unnecessary cesarean deliveries and medical interventions. HSV serology may be beneficial, however, in identifying seronegative pregnant women who have seropositive partners. Two recent studies have shown that 15% to 25% of couples have discordant HSV serologies and consequently are at risk of acquiring primary or initial-nonprimary HSV near term.4,5 These couples should be counseled concerning the use of condoms in the first and second trimester (50% reduction in HSV transmission) and abstinence in the third trimester.5 The seropositive partner also can be offered suppressive therapy, which provides a 48% reduction in the risk of HSV transmission.4 Ultimately, the difficulty lies in balancing the clinical benefits and cost of asymptomatic screening.11

CASE Resolved

The patient should be counseled that HSV infection rarely affects the fetus in utero, and transmission almost always occurs during the delivery process. This patient should receive prophylactic treatment with acyclovir beginning at 36 weeks of gestation to reduce the risk of an outbreak near the time of delivery. ●

CASE Pregnant woman with herpes simplex virus

A 26-year-old primigravid woman at 12 weeks of gestation indicates that she had an initial episode of herpes simplex virus (HSV) 6 years prior to presentation. Subsequently, she has had 1 to 2 recurrent episodes each year. She asks about the implications of HSV infection in pregnancy, particularly if anything can be done to prevent a recurrent outbreak near her due date and reduce the need for a cesarean delivery.

How would you counsel this patient?

Meet our perpetrator

Herpes simplex virus (HSV), the most prevalent sexually transmitted infection, is a DNA virus that has 2 major strains: HSV-1 and HSV-2. HSV-1 frequently is acquired in early childhood through nonsexual contact and typically causes orolabial and, less commonly, genital outbreaks. HSV-2 is almost always acquired through sexual contact and causes mainly genital outbreaks.1

There are 3 classifications of HSV infection: primary, initial-nonprimary, and recurrent (TABLE).

Primary infection refers to infection in a person without antibodies to either type of HSV.

Initial-nonprimary infection refers to acquisition of HSV-2 in a patient with preexisting antibodies to HSV-1 or vice versa. Patients tend to have more severe symptoms with primary as opposed to initial-nonprimary infection because, with the latter condition, preexisting antibodies provide partial protection against the opposing HSV type.1 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the seroprevalence of HSV-1 has decreased by approximately 23% in adolescents aged 14 to 19 years, with a resultant increase in the number of primary HSV-1 genital infections through oral-sexual contact in adulthood.2

Recurrent infection refers to reactivation of the same HSV type corresponding to the serum antibodies.

Clinical presentation

After an incubation period of 4 to 7 days, symptomatic patients with primary and initial-nonprimary genital HSV infections typically present with multiple, bilateral genital lesions at various stages of development. These lesions begin as small erythematous macules and then progress to papules, vesicles, pustules, ulcers, and crusted scabs over a period of 3 to 6 weeks1 (FIGURE). Patients also may present with fever, headache, fatigue, dysuria, and painful inguinal lymphadenopathy. Patients with recurrent infections usually experience prodromal itching or tingling for 2 to 5 days prior to the appearance of unilateral lesions, which persist for only 5 to 10 days. Systemic symptoms rarely are present. HSV-1 genital infection has a symptomatic recurrence rate of 20% to 50% within the first year, while HSV-2 has a recurrence rate of 70% to 90%.1

The majority of primary and initial-nonprimary infections are subclinical. One study showed that 74% of HSV-1 and 63% of HSV-2 initial genital herpes infections were asymptomatic.3 The relevance of this observation is that patients may not present for evaluation unless they experience a symptomatic recurrent infection. Meanwhile, they are asymptomatically shedding the virus and unknowingly transmitting HSV to their sexual partners. Asymptomatic viral shedding is more common with HSV-2 and is the most common source of transmission.4 The rate of asymptomatic shedding is unpredictable and has been shown to occur on 10% to 20% of days.1

Diagnosis and treatment

The gold standard for diagnosing HSV infection is viral culture; however, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays are faster to result and more sensitive.4,5 Both culture and PCR studies can distinguish the HSV type, allowing physicians to counsel patients regarding the expected clinical course, rate of recurrence, and implications for future pregnancies. After an initial infection, it may take up to 12 weeks for patients to develop detectable antibodies. Therefore, serology can be quite useful in determining the timing and classification of the infection. For example, a patient with HSV-2 isolated on viral culture or PCR and HSV-1 antibodies identified on serology is classified as having an initial-nonprimary infection.4

HSV treatment is dependent on the classification of infection. Treatment of primary and initial-nonprimary infection includes:

- acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily

- valacyclovir 1,000 mg orally twice daily, or

- famciclovir 250 mg orally 3 times daily for 7 to 10 days.

Ideally, treatment should be initiated within 72 hours of symptom onset.

Recurrent infections may be treated with:

- acyclovir 400 mg orally three times daily for 5 days

- valacyclovir 1,000 mg orally once daily for 5 days, or

- famciclovir 1,000 mg orally every 12 hours for 2 doses.

Ideally, treatment should begin within 24 hours of symptom onset.4,6

Patients with immunocompromising conditions, severe/frequent outbreaks (>6 per year), or who desire to reduce the risk of transmission to HSV-uninfected partners are candidates for chronic suppressive therapy. Suppressive options include acyclovir 400 mg orally twice daily, valacyclovir 500 mg orally once daily, and famciclovir 250 mg orally twice daily. Of note, there are many regimens available for acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir; all have similar efficacy in decreasing symptom severity, time to lesion healing, and duration of viral shedding.6 Acyclovir generally is the least expensive option.4

Continue to: Pregnancy and prevention...

Pregnancy and prevention

During pregnancy, 2% of women will acquire HSV, and 70% of these women will be asymptomatic.4,7 Approximately one-third to one-half of neonatal infections are caused by HSV-1.8 The most devastating complication of HSV infection in pregnancy is transmission to the newborn. Neonatal herpes is defined as the diagnosis of an HSV infection in a neonate within the first 28 days of life. The disease spectrum varies widely, and early recognition and treatment can substantially reduce the degree of morbidity and mortality associated with systemic infections.

HSV infection limited to the skin, eyes, and mucosal surfaces accounts for 45% of neonatal infections. When this condition is promptly recognized, neonates typically respond well to intravenous acyclovir, with prevention of systemic progression and overall good clinical outcomes. Infections of the central nervous system account for 30% of infections and are more difficult to diagnose due to the nonspecific symptomatology, including lethargy, poor feeding, seizures, and possible absence of lesions. The risk for death decreases from 50% to 6% with treatment; however, most neonates will still require close long-term surveillance for achievement of neurodevelopmental milestones and frequent ophthalmologic and hearing assessments.8,9 Disseminated HSV accounts for 25% of infections and can cause multiorgan failure, with a 31% risk for death despite treatment.5 Therefore, the cornerstone of managing HSV infection in pregnancy is focusing clinical efforts on prevention of transmission to the neonate.

More than 90% of neonatal herpes infections are acquired intrapartum,4 with 60% to 80% of cases occurring in women who developed HSV in the third trimester near the time of delivery.5 Neonates delivered vaginally to these women have a 30% to 50% risk of infection, compared to a <1% risk in neonates born to women with recurrent HSV.1,5,10 The discrepancy in infection risk is thought to be secondary to higher HSV viral loads after an initial infection as opposed to a recurrent infection. Furthermore, acquisition of HSV near term does not allow for the 6 to 12 weeks necessary to develop antibodies that can cross the placenta and provide neonatal protection. The risk of vertical transmission is approximately 25% with an initial-nonprimary episode, reflecting the partial protection afforded by antibody against the other viral serotype.11

Prophylactic therapy has been shown to reduce the rate of asymptomatic viral shedding and recurrent infections near term.7 To reduce the risk of intrapartum transmission, women with a history of HSV prior to or during pregnancy should be treated with acyclovir 400 mg orally 3 times daily starting at 36 weeks of gestation. When patients present with rupture of membranes or labor, they should be asked about prodromal symptoms and thoroughly examined. If prodromal symptoms are present or genital lesions identified, patients should undergo cesarean delivery.12 Some experts also recommend cesarean delivery for women who acquire primary or initial-nonprimary HSV infection in the third trimester due to higher viral loads and potential lack of antibodies at the time of delivery.8,12 However, this recommendation has not been validated by a rigorous prospective randomized clinical trial. When clinically feasible, avoidance of invasive fetal monitoring during labor also has been shown to decrease the risk of HSV transmission by approximately 84% in women with asymptomatic viral shedding.12 This concept may be extrapolated to include assisted delivery with vacuum or forceps.

Universal screening for HSV infection in pregnancy is controversial and widely debated. Most HSV seropositive patients are asymptomatic and will not report a history of HSV infection at the initial prenatal visit. Universal screening, therefore, may increase the rate of unnecessary cesarean deliveries and medical interventions. HSV serology may be beneficial, however, in identifying seronegative pregnant women who have seropositive partners. Two recent studies have shown that 15% to 25% of couples have discordant HSV serologies and consequently are at risk of acquiring primary or initial-nonprimary HSV near term.4,5 These couples should be counseled concerning the use of condoms in the first and second trimester (50% reduction in HSV transmission) and abstinence in the third trimester.5 The seropositive partner also can be offered suppressive therapy, which provides a 48% reduction in the risk of HSV transmission.4 Ultimately, the difficulty lies in balancing the clinical benefits and cost of asymptomatic screening.11

CASE Resolved

The patient should be counseled that HSV infection rarely affects the fetus in utero, and transmission almost always occurs during the delivery process. This patient should receive prophylactic treatment with acyclovir beginning at 36 weeks of gestation to reduce the risk of an outbreak near the time of delivery. ●

- Gnann JW, Whitley RJ. Genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:666-674.

- Bradley H, Markowitz LE, Gibson T, et al. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 — United States, 1999–2010. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:325-333.

- Bernstein DI, Bellamy AR, Hook EW, et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and antibody response to primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in young women. Clin Infec Dis. 2012;56:344-351.

- Brown ZA, Gardella C, Wald A, et al. Genital herpes complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:426-437.

- Corey L, Wald A. Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1376-1385.

- Albrecht MA. Treatment of genital herpes simplex virus infection. UpToDate website. Updated June 4, 2019. Accessed March 21, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-genital-herpes-simplex-virus-infection?search=hsv+treatment

- Sheffield J, Wendel G Jr, Stuart G, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis to prevent herpes simplex virus recurrence at delivery: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1396-1403.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of genital herpes in pregnancy: ACOG practice bulletin summary, number 220. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:1236-1238.

- Kimberlin DW. Oral acyclovir suppression after neonatal herpes. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1284-1292.

- Brown ZA, Benedetti J, Ashley R, et al. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection in relation to asymptomatic maternal infection at the time of labor. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1247-1252.

- Chatroux IC, Hersh AR, Caughey AB. Herpes simplex virus serotyping in pregnant women with a history of genital herpes and an outbreak in the third trimester. a cost effectiveness analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:63-71.

- Brown ZA, Wald A, Morrow RA, et al. Effect of serologic status and cesarean delivery on transmission rates of herpes simplex virus from mother to infant. JAMA. 2003;289:203-209.

- Gnann JW, Whitley RJ. Genital herpes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:666-674.

- Bradley H, Markowitz LE, Gibson T, et al. Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 — United States, 1999–2010. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:325-333.

- Bernstein DI, Bellamy AR, Hook EW, et al. Epidemiology, clinical presentation, and antibody response to primary infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in young women. Clin Infec Dis. 2012;56:344-351.

- Brown ZA, Gardella C, Wald A, et al. Genital herpes complicating pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:426-437.

- Corey L, Wald A. Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1376-1385.

- Albrecht MA. Treatment of genital herpes simplex virus infection. UpToDate website. Updated June 4, 2019. Accessed March 21, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-genital-herpes-simplex-virus-infection?search=hsv+treatment

- Sheffield J, Wendel G Jr, Stuart G, et al. Acyclovir prophylaxis to prevent herpes simplex virus recurrence at delivery: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:1396-1403.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Management of genital herpes in pregnancy: ACOG practice bulletin summary, number 220. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:1236-1238.

- Kimberlin DW. Oral acyclovir suppression after neonatal herpes. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1284-1292.

- Brown ZA, Benedetti J, Ashley R, et al. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection in relation to asymptomatic maternal infection at the time of labor. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1247-1252.

- Chatroux IC, Hersh AR, Caughey AB. Herpes simplex virus serotyping in pregnant women with a history of genital herpes and an outbreak in the third trimester. a cost effectiveness analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:63-71.

- Brown ZA, Wald A, Morrow RA, et al. Effect of serologic status and cesarean delivery on transmission rates of herpes simplex virus from mother to infant. JAMA. 2003;289:203-209.