User login

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an uncommon B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) characterized by the translocation, t(11;14), that results in aberrant expression of cyclin D1.1 The clinical presentation varies significantly from asymptomatic to rapidly enlarging lymph nodes, necessitating immediate treatment. Treatment approaches to newly diagnosed MCL correspondingly vary to match the clinical presentation, but they also reflect the bias of individual providers. No treatment is curative, so different treatment philosophies heavily influence management strategies. Mantle cell lymphoma was first described in the 1990s as a unique pathobiologic entity, and it is only now developing its own set of treatment principles distinct from other lymphomas.2 As novel targeted therapies become available, fundamental questions regarding the best treatment approach are certain to evolve.

Traditional Intensive Treatment

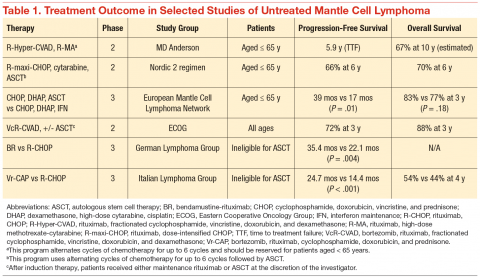

The clinical challenge of treating patients with MCL centers on its propensity to relapse quickly after initial therapy. Although most patients will respond to the initial therapy, the duration of their remissions are disappointingly short. The R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) regimens can induce a complete response in the majority of patients, but they invariably relapse within 18 months of finishing therapy. Recognition of this problem led investigators to test highly intensive regimens designed to maximize the depth of remission often followed by autologous stem cell transplant. The highly intensive regimens are successful at extending remission durations to > 5 years in most cases, but at the cost of significant myelotoxicity and a nontrivial risk of death during induction therapy (Table 1).

In a subset analysis of a hyper-CVAD (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone) study in MCL, it was observed that patients aged < 65 years had a better survival rate than did older patients.3 Accordingly, these regimens are largely restricted to patients aged < 65 years, which is only a minority of patients with MCL. Importantly, despite initial enthusiasm for the impressive rates of remission, most data suggest that these regimens are not curative.

Nonintensive Treatment

Until recently, patients aged > 65 years or those with significant comorbidities did not have effective treatment options that resulted in durable remissions. Most patients were treated with R-CHOP therapy, and the median survival was only 2 to 3 years.4 Interferon maintenance was frequently used but was largely ineffective at prolongation of remission. Treatment patterns changed quickly after the preliminary results of the randomized StiL (Study Group Indolent Lymphomas) study demonstrated that bendamustine-rituximab (BR) could induce durable remissions with less toxicity than that of R-CHOP therapy (Table 1).5 The superiority of BR over R-CHOP at inducing remissions in MCL was subsequently confirmed in the U.S.-led BRIGHT study; this regimen has become a popular regimen for patients aged > 65 years.6 Despite improved remission rate with less toxicity, however, the BR induction regimen still does not adequately address the problem of short durations of remission.

In a phase 3 study, the European MCL Network demonstrated that the use of maintenance rituximab after induction therapy prolonged both progression-free survival (PFS) as well as overall survival (when given after R-CHOP) compared with interferon maintenance.7 Many providers have extrapolated the benefits seen with rituximab maintenance after R-CHOP to all induction regimens, and rituximab maintenance is increasingly offered to older patients after their induction therapy. An important detail of this study is that rituximab was given indefinitely during maintenance and was not capped at 2 years, as often is done for maintenance treatment in other indolent lymphomas.

A landmark randomized study was recently published that demonstrated an advantage of substituting bortezomib for vincristine in the initial regimen.8 In a phase 3 study of 487 patients, the Vr-CAP (bortezomib in combination with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone) regimen demonstrated an improvement in median PFS over R-CHOP after 40 months of followup (24.7 months vs 14.4 months; hazard radio [HR] 0.63; P < .001) (Table 1). Of particular note, however, is that for patients who achieved a complete remission, the median duration of remission was significantly longer than that of R-CHOP (42.1 months vs 18.0 months; HR 0.63; P < .001). These data suggest that not only is Vr-CAP superior to R-CHOP as a whole, but also that some patients are particularly sensitive to bortezomib, resulting in durable remissions.

Novel Targeted Agents

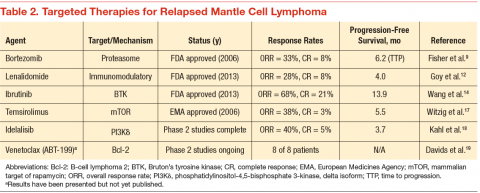

Since 2006, 3 novel targeted agents have been approved for use in relapsed MCL, and many others are currently in clinical trials (Table 2). Bortezomib is approved for use in both the relapsed and upfront setting and demonstrates clear activity in MCL; however, no biomarker currently exists to help understand which patients will respond. Furthermore, most responses to single agents are partial and short-lived.9

Lenalidomide is an oral immunomodulatory agent that works in NHL through a variety of direct and indirect mechanisms.10 As a single agent, lenalidomide has shown activity in a number of studies and can be combined with rituximab without an apparent increase in the toxicity profile.11-13 The EMERGE trial tested lenalidomide as a single agent at 25 mg (every 21 days out of a 28-day cycle) in patients who had previously been treated with bortezomib. In 128 patients, the overall response rate (RR) was 28% with a complete RR of 7.5%. Although these numbers are modest, long-term data from the NHL-003 trial show a subset of patients with durations of remissions nearing 4 years.11 Thus, a biomarker for lenalidomide that predicts response would be of great

clinical utility.

Perhaps of even greater interest have been the clinical results seen with the use of the oral Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor, ibrutinib. In 111 patients with relapsed MCL treated with ibrutinib 560 mg, the overall RR was 68% with a complete RR of 21%.14 Most patients tolerated therapy very well, and the duration of remission was estimated at 17.5 months. This was a very impressive result with an agent that is tolerable by most patients with MCL.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Mantle cell lymphoma remains a clinical challenge to many providers due to the heterogeneity in the clinical presentation and the lack of consensus regarding the optimal management strategy. The most commonly recommended approach remains to offer highly intensive chemotherapy programs to patients aged < 65 years, but the introduction of novel active agents into the treatment paradigm is beginning to challenge the assumption that all patients need aggressive therapy.

Future research directions should include predictive biomarkers to enhance treatment decisions. Researchers also should begin to understand the toxicity profile and efficacy of the novel targeted agents when used in combination. Early, informative reports are available regarding ibrutinib when added to both rituximab and BR.15,16 Important research questions will include the long-term effects of extended duration therapy (maintenance) paradigms as well as the introduction of novel molecular monitoring methods, such as circulating tumor DNA and circulating tumor cells, to help guide clinical decisions. In a disease with a reportedly dismal outcome, the near future holds much promise as the MCL treatment landscape evolves at a rapid pace.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to continue reading.

1. Pérez-Galán P, Dreyling M, Wiestner A. Mantle cell lymphoma: biology, pathogenesis, and the molecular basis of treatment in the genomic era. Blood. 2011;117(1):26-38.

2. Raffeld M, Jaffe ES. bcl-1, t(11;14), and mantle cell-derived lymphomas. Blood. 1991;78(2):259-263.

3. Romaguera JE, Fayad L, Rodriguez MA, et al. High rate of durable remissions after treatment of newly diagnosed aggressive mantle-cell lymphoma with rituximab plus hyper-CVAD alternating with rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(28):7013-7023.

4. Lenz G, Dreyling M, Hoster E, et al. Immunochemotherapy with rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone significantly improves response and time to treatment failure, but not long-term outcome in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(9):1984-1992.

5. Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al; Study group indolent Lymphomas (StiL). Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9873):1203-1210.

6. Flinn IW, van der Jagt R, Kahl BS, et al. Randomized trial of bendamustinerituximab or R-CHOP/R-CVP in first-line treatment of indolent NHL or MCL: the BRIGHT study. Blood. 2014;123(19):2944-2952.

7. Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hoster E, Hermine O, et al. Treatment of older patients with mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(6):520-531.

8. Ro bak T, Huang H, Jin J, et al; LYM-3002 Investigators. Bortezomib-based therapy for newly diagnosed mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(10):944-953.

9. Fisher RI, Bernstein SH, Kahl BS, et al. Multicenter phase II study of bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(30):4867-4874.

10 . Kritharis A, Coyle M, Sharma J, Evens AM. Lenalidomide in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: biologic perspectives and therapeutic opportunities [published online ahead of print March 3, 2015]. Blood. pii: blood-2014-11-567792.

11 . Zinzani PL, Vose JM, Czuczman MS, et al. Long-term follow-up of lenalidomide in relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma: subset analysis of the NHL-003 study. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(11):2892-2897.

12 . Goy A, Sinha R, Williams ME, et al. Single-agent lenalidomide in patients with mantle-cell lymphoma who relapsed or progressed after or were refractory to bortezomib: phase II MCL-001 (EMERGE) Study [published online ahead of print September 3, 2013]. J Clin Oncol. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2835.

13 . Chong EA, Ahmadi T, Aqui NA, et al. Combination of lenalidomide and rituximab overcomes rituximab-resistance in patients with indolent B-cell and mantle cell lymphomas [published online ahead of print January 28, 2015]. Clin Cancer Res. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2221.

14 . Wang ML, Rule S, Martin P, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(6):507-516.

15 . Wang ML, Hagemeister F, Westin JR, et al. Ibrutinib and rituximab are an efficacious and safe combination in relapsed mantle cell lymphoma: preliminary results from a phase II clinical trial. Blood. 2014;124(21):627.

16 . Maddocks K, Christian B, Jaglowski S, et al. A phase 1/1b study of rituximab, bendamustine, and ibrutinib in patients with untreated and relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125(2):242-248.

17 . Witzig TE, Geyer SM, Ghobrial I, et al. Phase II trial of single-agent temsirolimus (CCI-779) for relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(23):5347-5356.

18 . Kahl BS, Spurgeon SE, Furman RR, et al. A phase 1 study of the PI3K inhibitor idelalisib in patients with relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). Blood. 2014;123(22):3398-3405.

19. Davids MS, Roberts AW, Anderson MA, et al. The BCL-2-specific BH3-mimetic ABT-199 (GDC-0199) is active and well-tolerated in patients with relapsed nonhodgkin lymphoma: interim results of a phase I study. Blood. 2012;120(21): Abstract 304.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an uncommon B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) characterized by the translocation, t(11;14), that results in aberrant expression of cyclin D1.1 The clinical presentation varies significantly from asymptomatic to rapidly enlarging lymph nodes, necessitating immediate treatment. Treatment approaches to newly diagnosed MCL correspondingly vary to match the clinical presentation, but they also reflect the bias of individual providers. No treatment is curative, so different treatment philosophies heavily influence management strategies. Mantle cell lymphoma was first described in the 1990s as a unique pathobiologic entity, and it is only now developing its own set of treatment principles distinct from other lymphomas.2 As novel targeted therapies become available, fundamental questions regarding the best treatment approach are certain to evolve.

Traditional Intensive Treatment

The clinical challenge of treating patients with MCL centers on its propensity to relapse quickly after initial therapy. Although most patients will respond to the initial therapy, the duration of their remissions are disappointingly short. The R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) regimens can induce a complete response in the majority of patients, but they invariably relapse within 18 months of finishing therapy. Recognition of this problem led investigators to test highly intensive regimens designed to maximize the depth of remission often followed by autologous stem cell transplant. The highly intensive regimens are successful at extending remission durations to > 5 years in most cases, but at the cost of significant myelotoxicity and a nontrivial risk of death during induction therapy (Table 1).

In a subset analysis of a hyper-CVAD (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone) study in MCL, it was observed that patients aged < 65 years had a better survival rate than did older patients.3 Accordingly, these regimens are largely restricted to patients aged < 65 years, which is only a minority of patients with MCL. Importantly, despite initial enthusiasm for the impressive rates of remission, most data suggest that these regimens are not curative.

Nonintensive Treatment

Until recently, patients aged > 65 years or those with significant comorbidities did not have effective treatment options that resulted in durable remissions. Most patients were treated with R-CHOP therapy, and the median survival was only 2 to 3 years.4 Interferon maintenance was frequently used but was largely ineffective at prolongation of remission. Treatment patterns changed quickly after the preliminary results of the randomized StiL (Study Group Indolent Lymphomas) study demonstrated that bendamustine-rituximab (BR) could induce durable remissions with less toxicity than that of R-CHOP therapy (Table 1).5 The superiority of BR over R-CHOP at inducing remissions in MCL was subsequently confirmed in the U.S.-led BRIGHT study; this regimen has become a popular regimen for patients aged > 65 years.6 Despite improved remission rate with less toxicity, however, the BR induction regimen still does not adequately address the problem of short durations of remission.

In a phase 3 study, the European MCL Network demonstrated that the use of maintenance rituximab after induction therapy prolonged both progression-free survival (PFS) as well as overall survival (when given after R-CHOP) compared with interferon maintenance.7 Many providers have extrapolated the benefits seen with rituximab maintenance after R-CHOP to all induction regimens, and rituximab maintenance is increasingly offered to older patients after their induction therapy. An important detail of this study is that rituximab was given indefinitely during maintenance and was not capped at 2 years, as often is done for maintenance treatment in other indolent lymphomas.

A landmark randomized study was recently published that demonstrated an advantage of substituting bortezomib for vincristine in the initial regimen.8 In a phase 3 study of 487 patients, the Vr-CAP (bortezomib in combination with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone) regimen demonstrated an improvement in median PFS over R-CHOP after 40 months of followup (24.7 months vs 14.4 months; hazard radio [HR] 0.63; P < .001) (Table 1). Of particular note, however, is that for patients who achieved a complete remission, the median duration of remission was significantly longer than that of R-CHOP (42.1 months vs 18.0 months; HR 0.63; P < .001). These data suggest that not only is Vr-CAP superior to R-CHOP as a whole, but also that some patients are particularly sensitive to bortezomib, resulting in durable remissions.

Novel Targeted Agents

Since 2006, 3 novel targeted agents have been approved for use in relapsed MCL, and many others are currently in clinical trials (Table 2). Bortezomib is approved for use in both the relapsed and upfront setting and demonstrates clear activity in MCL; however, no biomarker currently exists to help understand which patients will respond. Furthermore, most responses to single agents are partial and short-lived.9

Lenalidomide is an oral immunomodulatory agent that works in NHL through a variety of direct and indirect mechanisms.10 As a single agent, lenalidomide has shown activity in a number of studies and can be combined with rituximab without an apparent increase in the toxicity profile.11-13 The EMERGE trial tested lenalidomide as a single agent at 25 mg (every 21 days out of a 28-day cycle) in patients who had previously been treated with bortezomib. In 128 patients, the overall response rate (RR) was 28% with a complete RR of 7.5%. Although these numbers are modest, long-term data from the NHL-003 trial show a subset of patients with durations of remissions nearing 4 years.11 Thus, a biomarker for lenalidomide that predicts response would be of great

clinical utility.

Perhaps of even greater interest have been the clinical results seen with the use of the oral Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor, ibrutinib. In 111 patients with relapsed MCL treated with ibrutinib 560 mg, the overall RR was 68% with a complete RR of 21%.14 Most patients tolerated therapy very well, and the duration of remission was estimated at 17.5 months. This was a very impressive result with an agent that is tolerable by most patients with MCL.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Mantle cell lymphoma remains a clinical challenge to many providers due to the heterogeneity in the clinical presentation and the lack of consensus regarding the optimal management strategy. The most commonly recommended approach remains to offer highly intensive chemotherapy programs to patients aged < 65 years, but the introduction of novel active agents into the treatment paradigm is beginning to challenge the assumption that all patients need aggressive therapy.

Future research directions should include predictive biomarkers to enhance treatment decisions. Researchers also should begin to understand the toxicity profile and efficacy of the novel targeted agents when used in combination. Early, informative reports are available regarding ibrutinib when added to both rituximab and BR.15,16 Important research questions will include the long-term effects of extended duration therapy (maintenance) paradigms as well as the introduction of novel molecular monitoring methods, such as circulating tumor DNA and circulating tumor cells, to help guide clinical decisions. In a disease with a reportedly dismal outcome, the near future holds much promise as the MCL treatment landscape evolves at a rapid pace.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to continue reading.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is an uncommon B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) characterized by the translocation, t(11;14), that results in aberrant expression of cyclin D1.1 The clinical presentation varies significantly from asymptomatic to rapidly enlarging lymph nodes, necessitating immediate treatment. Treatment approaches to newly diagnosed MCL correspondingly vary to match the clinical presentation, but they also reflect the bias of individual providers. No treatment is curative, so different treatment philosophies heavily influence management strategies. Mantle cell lymphoma was first described in the 1990s as a unique pathobiologic entity, and it is only now developing its own set of treatment principles distinct from other lymphomas.2 As novel targeted therapies become available, fundamental questions regarding the best treatment approach are certain to evolve.

Traditional Intensive Treatment

The clinical challenge of treating patients with MCL centers on its propensity to relapse quickly after initial therapy. Although most patients will respond to the initial therapy, the duration of their remissions are disappointingly short. The R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) regimens can induce a complete response in the majority of patients, but they invariably relapse within 18 months of finishing therapy. Recognition of this problem led investigators to test highly intensive regimens designed to maximize the depth of remission often followed by autologous stem cell transplant. The highly intensive regimens are successful at extending remission durations to > 5 years in most cases, but at the cost of significant myelotoxicity and a nontrivial risk of death during induction therapy (Table 1).

In a subset analysis of a hyper-CVAD (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone) study in MCL, it was observed that patients aged < 65 years had a better survival rate than did older patients.3 Accordingly, these regimens are largely restricted to patients aged < 65 years, which is only a minority of patients with MCL. Importantly, despite initial enthusiasm for the impressive rates of remission, most data suggest that these regimens are not curative.

Nonintensive Treatment

Until recently, patients aged > 65 years or those with significant comorbidities did not have effective treatment options that resulted in durable remissions. Most patients were treated with R-CHOP therapy, and the median survival was only 2 to 3 years.4 Interferon maintenance was frequently used but was largely ineffective at prolongation of remission. Treatment patterns changed quickly after the preliminary results of the randomized StiL (Study Group Indolent Lymphomas) study demonstrated that bendamustine-rituximab (BR) could induce durable remissions with less toxicity than that of R-CHOP therapy (Table 1).5 The superiority of BR over R-CHOP at inducing remissions in MCL was subsequently confirmed in the U.S.-led BRIGHT study; this regimen has become a popular regimen for patients aged > 65 years.6 Despite improved remission rate with less toxicity, however, the BR induction regimen still does not adequately address the problem of short durations of remission.

In a phase 3 study, the European MCL Network demonstrated that the use of maintenance rituximab after induction therapy prolonged both progression-free survival (PFS) as well as overall survival (when given after R-CHOP) compared with interferon maintenance.7 Many providers have extrapolated the benefits seen with rituximab maintenance after R-CHOP to all induction regimens, and rituximab maintenance is increasingly offered to older patients after their induction therapy. An important detail of this study is that rituximab was given indefinitely during maintenance and was not capped at 2 years, as often is done for maintenance treatment in other indolent lymphomas.

A landmark randomized study was recently published that demonstrated an advantage of substituting bortezomib for vincristine in the initial regimen.8 In a phase 3 study of 487 patients, the Vr-CAP (bortezomib in combination with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone) regimen demonstrated an improvement in median PFS over R-CHOP after 40 months of followup (24.7 months vs 14.4 months; hazard radio [HR] 0.63; P < .001) (Table 1). Of particular note, however, is that for patients who achieved a complete remission, the median duration of remission was significantly longer than that of R-CHOP (42.1 months vs 18.0 months; HR 0.63; P < .001). These data suggest that not only is Vr-CAP superior to R-CHOP as a whole, but also that some patients are particularly sensitive to bortezomib, resulting in durable remissions.

Novel Targeted Agents

Since 2006, 3 novel targeted agents have been approved for use in relapsed MCL, and many others are currently in clinical trials (Table 2). Bortezomib is approved for use in both the relapsed and upfront setting and demonstrates clear activity in MCL; however, no biomarker currently exists to help understand which patients will respond. Furthermore, most responses to single agents are partial and short-lived.9

Lenalidomide is an oral immunomodulatory agent that works in NHL through a variety of direct and indirect mechanisms.10 As a single agent, lenalidomide has shown activity in a number of studies and can be combined with rituximab without an apparent increase in the toxicity profile.11-13 The EMERGE trial tested lenalidomide as a single agent at 25 mg (every 21 days out of a 28-day cycle) in patients who had previously been treated with bortezomib. In 128 patients, the overall response rate (RR) was 28% with a complete RR of 7.5%. Although these numbers are modest, long-term data from the NHL-003 trial show a subset of patients with durations of remissions nearing 4 years.11 Thus, a biomarker for lenalidomide that predicts response would be of great

clinical utility.

Perhaps of even greater interest have been the clinical results seen with the use of the oral Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor, ibrutinib. In 111 patients with relapsed MCL treated with ibrutinib 560 mg, the overall RR was 68% with a complete RR of 21%.14 Most patients tolerated therapy very well, and the duration of remission was estimated at 17.5 months. This was a very impressive result with an agent that is tolerable by most patients with MCL.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Mantle cell lymphoma remains a clinical challenge to many providers due to the heterogeneity in the clinical presentation and the lack of consensus regarding the optimal management strategy. The most commonly recommended approach remains to offer highly intensive chemotherapy programs to patients aged < 65 years, but the introduction of novel active agents into the treatment paradigm is beginning to challenge the assumption that all patients need aggressive therapy.

Future research directions should include predictive biomarkers to enhance treatment decisions. Researchers also should begin to understand the toxicity profile and efficacy of the novel targeted agents when used in combination. Early, informative reports are available regarding ibrutinib when added to both rituximab and BR.15,16 Important research questions will include the long-term effects of extended duration therapy (maintenance) paradigms as well as the introduction of novel molecular monitoring methods, such as circulating tumor DNA and circulating tumor cells, to help guide clinical decisions. In a disease with a reportedly dismal outcome, the near future holds much promise as the MCL treatment landscape evolves at a rapid pace.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to continue reading.

1. Pérez-Galán P, Dreyling M, Wiestner A. Mantle cell lymphoma: biology, pathogenesis, and the molecular basis of treatment in the genomic era. Blood. 2011;117(1):26-38.

2. Raffeld M, Jaffe ES. bcl-1, t(11;14), and mantle cell-derived lymphomas. Blood. 1991;78(2):259-263.

3. Romaguera JE, Fayad L, Rodriguez MA, et al. High rate of durable remissions after treatment of newly diagnosed aggressive mantle-cell lymphoma with rituximab plus hyper-CVAD alternating with rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(28):7013-7023.

4. Lenz G, Dreyling M, Hoster E, et al. Immunochemotherapy with rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone significantly improves response and time to treatment failure, but not long-term outcome in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(9):1984-1992.

5. Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al; Study group indolent Lymphomas (StiL). Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9873):1203-1210.

6. Flinn IW, van der Jagt R, Kahl BS, et al. Randomized trial of bendamustinerituximab or R-CHOP/R-CVP in first-line treatment of indolent NHL or MCL: the BRIGHT study. Blood. 2014;123(19):2944-2952.

7. Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hoster E, Hermine O, et al. Treatment of older patients with mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(6):520-531.

8. Ro bak T, Huang H, Jin J, et al; LYM-3002 Investigators. Bortezomib-based therapy for newly diagnosed mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(10):944-953.

9. Fisher RI, Bernstein SH, Kahl BS, et al. Multicenter phase II study of bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(30):4867-4874.

10 . Kritharis A, Coyle M, Sharma J, Evens AM. Lenalidomide in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: biologic perspectives and therapeutic opportunities [published online ahead of print March 3, 2015]. Blood. pii: blood-2014-11-567792.

11 . Zinzani PL, Vose JM, Czuczman MS, et al. Long-term follow-up of lenalidomide in relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma: subset analysis of the NHL-003 study. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(11):2892-2897.

12 . Goy A, Sinha R, Williams ME, et al. Single-agent lenalidomide in patients with mantle-cell lymphoma who relapsed or progressed after or were refractory to bortezomib: phase II MCL-001 (EMERGE) Study [published online ahead of print September 3, 2013]. J Clin Oncol. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2835.

13 . Chong EA, Ahmadi T, Aqui NA, et al. Combination of lenalidomide and rituximab overcomes rituximab-resistance in patients with indolent B-cell and mantle cell lymphomas [published online ahead of print January 28, 2015]. Clin Cancer Res. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2221.

14 . Wang ML, Rule S, Martin P, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(6):507-516.

15 . Wang ML, Hagemeister F, Westin JR, et al. Ibrutinib and rituximab are an efficacious and safe combination in relapsed mantle cell lymphoma: preliminary results from a phase II clinical trial. Blood. 2014;124(21):627.

16 . Maddocks K, Christian B, Jaglowski S, et al. A phase 1/1b study of rituximab, bendamustine, and ibrutinib in patients with untreated and relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125(2):242-248.

17 . Witzig TE, Geyer SM, Ghobrial I, et al. Phase II trial of single-agent temsirolimus (CCI-779) for relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(23):5347-5356.

18 . Kahl BS, Spurgeon SE, Furman RR, et al. A phase 1 study of the PI3K inhibitor idelalisib in patients with relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). Blood. 2014;123(22):3398-3405.

19. Davids MS, Roberts AW, Anderson MA, et al. The BCL-2-specific BH3-mimetic ABT-199 (GDC-0199) is active and well-tolerated in patients with relapsed nonhodgkin lymphoma: interim results of a phase I study. Blood. 2012;120(21): Abstract 304.

1. Pérez-Galán P, Dreyling M, Wiestner A. Mantle cell lymphoma: biology, pathogenesis, and the molecular basis of treatment in the genomic era. Blood. 2011;117(1):26-38.

2. Raffeld M, Jaffe ES. bcl-1, t(11;14), and mantle cell-derived lymphomas. Blood. 1991;78(2):259-263.

3. Romaguera JE, Fayad L, Rodriguez MA, et al. High rate of durable remissions after treatment of newly diagnosed aggressive mantle-cell lymphoma with rituximab plus hyper-CVAD alternating with rituximab plus high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(28):7013-7023.

4. Lenz G, Dreyling M, Hoster E, et al. Immunochemotherapy with rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone significantly improves response and time to treatment failure, but not long-term outcome in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(9):1984-1992.

5. Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al; Study group indolent Lymphomas (StiL). Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9873):1203-1210.

6. Flinn IW, van der Jagt R, Kahl BS, et al. Randomized trial of bendamustinerituximab or R-CHOP/R-CVP in first-line treatment of indolent NHL or MCL: the BRIGHT study. Blood. 2014;123(19):2944-2952.

7. Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hoster E, Hermine O, et al. Treatment of older patients with mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(6):520-531.

8. Ro bak T, Huang H, Jin J, et al; LYM-3002 Investigators. Bortezomib-based therapy for newly diagnosed mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(10):944-953.

9. Fisher RI, Bernstein SH, Kahl BS, et al. Multicenter phase II study of bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(30):4867-4874.

10 . Kritharis A, Coyle M, Sharma J, Evens AM. Lenalidomide in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: biologic perspectives and therapeutic opportunities [published online ahead of print March 3, 2015]. Blood. pii: blood-2014-11-567792.

11 . Zinzani PL, Vose JM, Czuczman MS, et al. Long-term follow-up of lenalidomide in relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma: subset analysis of the NHL-003 study. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(11):2892-2897.

12 . Goy A, Sinha R, Williams ME, et al. Single-agent lenalidomide in patients with mantle-cell lymphoma who relapsed or progressed after or were refractory to bortezomib: phase II MCL-001 (EMERGE) Study [published online ahead of print September 3, 2013]. J Clin Oncol. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2835.

13 . Chong EA, Ahmadi T, Aqui NA, et al. Combination of lenalidomide and rituximab overcomes rituximab-resistance in patients with indolent B-cell and mantle cell lymphomas [published online ahead of print January 28, 2015]. Clin Cancer Res. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2221.

14 . Wang ML, Rule S, Martin P, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(6):507-516.

15 . Wang ML, Hagemeister F, Westin JR, et al. Ibrutinib and rituximab are an efficacious and safe combination in relapsed mantle cell lymphoma: preliminary results from a phase II clinical trial. Blood. 2014;124(21):627.

16 . Maddocks K, Christian B, Jaglowski S, et al. A phase 1/1b study of rituximab, bendamustine, and ibrutinib in patients with untreated and relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125(2):242-248.

17 . Witzig TE, Geyer SM, Ghobrial I, et al. Phase II trial of single-agent temsirolimus (CCI-779) for relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(23):5347-5356.

18 . Kahl BS, Spurgeon SE, Furman RR, et al. A phase 1 study of the PI3K inhibitor idelalisib in patients with relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). Blood. 2014;123(22):3398-3405.

19. Davids MS, Roberts AW, Anderson MA, et al. The BCL-2-specific BH3-mimetic ABT-199 (GDC-0199) is active and well-tolerated in patients with relapsed nonhodgkin lymphoma: interim results of a phase I study. Blood. 2012;120(21): Abstract 304.