User login

CASE

A 48-year-old man comes to your clinic with a dark nevus on his right upper arm that appeared 2 months earlier. He says that the lesion has continued to grow and has bled (he thought because he initially picked at it). On exam, there is a 7-mm brown papule with 2 black dots and slightly asymmetric borders.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Melanoma is the fifth leading cause of new cancer cases annually, with > 96,000 new cases in 2019.1 Overall, melanoma is more common in men and in Whites, with 48% diagnosed in people ages 55 to 74.1 The past 2 decades have seen numerous developments in the diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance of melanoma. This article covers recommendations, controversies, and issues that require future study. It does not cover uveal or mucosal melanoma.

Evaluating a patient with a new or changing nevus

Known risk factors for melanoma include a changing nevus, indoor tanning, older age, many melanocytic nevi, history of a dysplastic nevus or of blistering sunburns during teen years, red or blonde hair, large congenital nevus, Fitzpatrick skin type I or II, high socioeconomic status, personal or family history of melanoma, and intermittent high-intensity sun exposure.2-3 Presence of 1 or more of these risk factors should lower the threshold for biopsy.

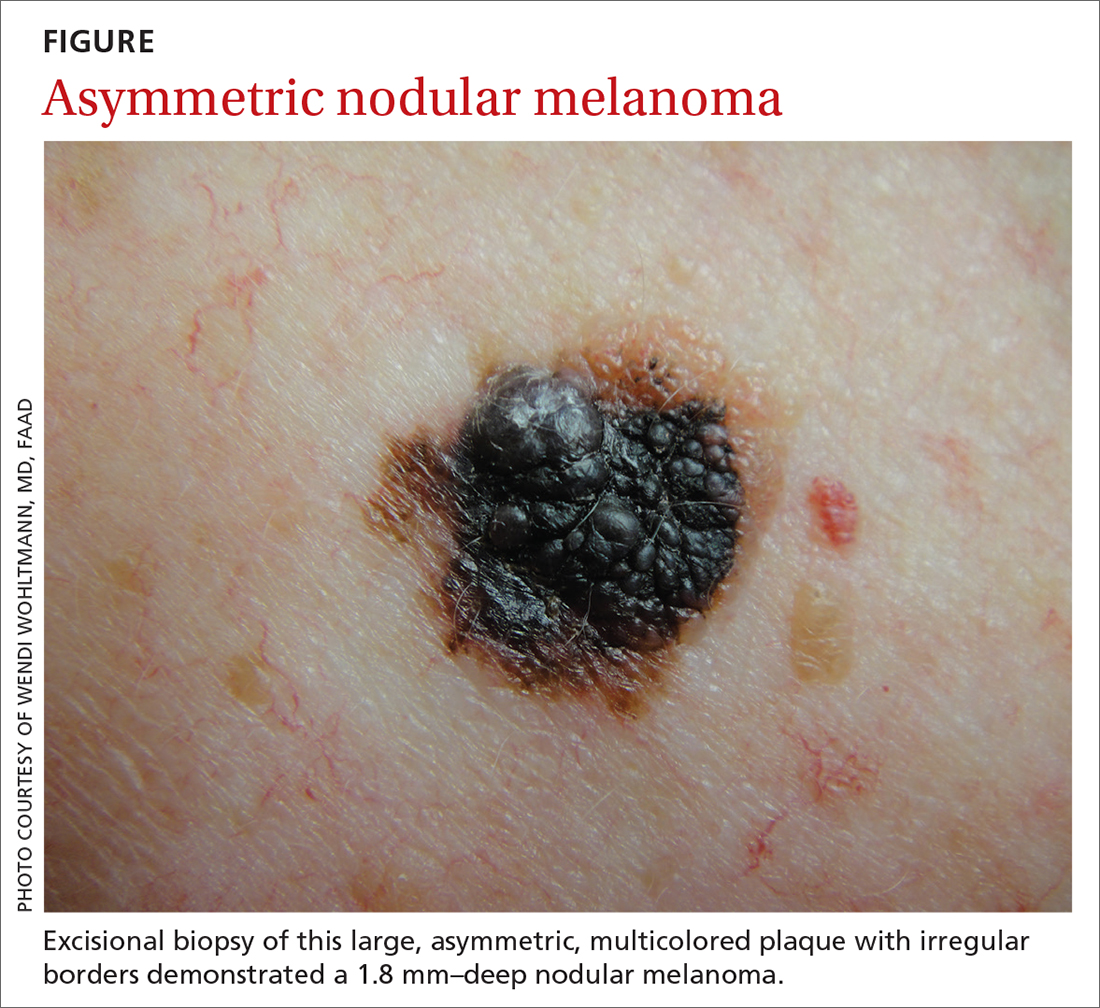

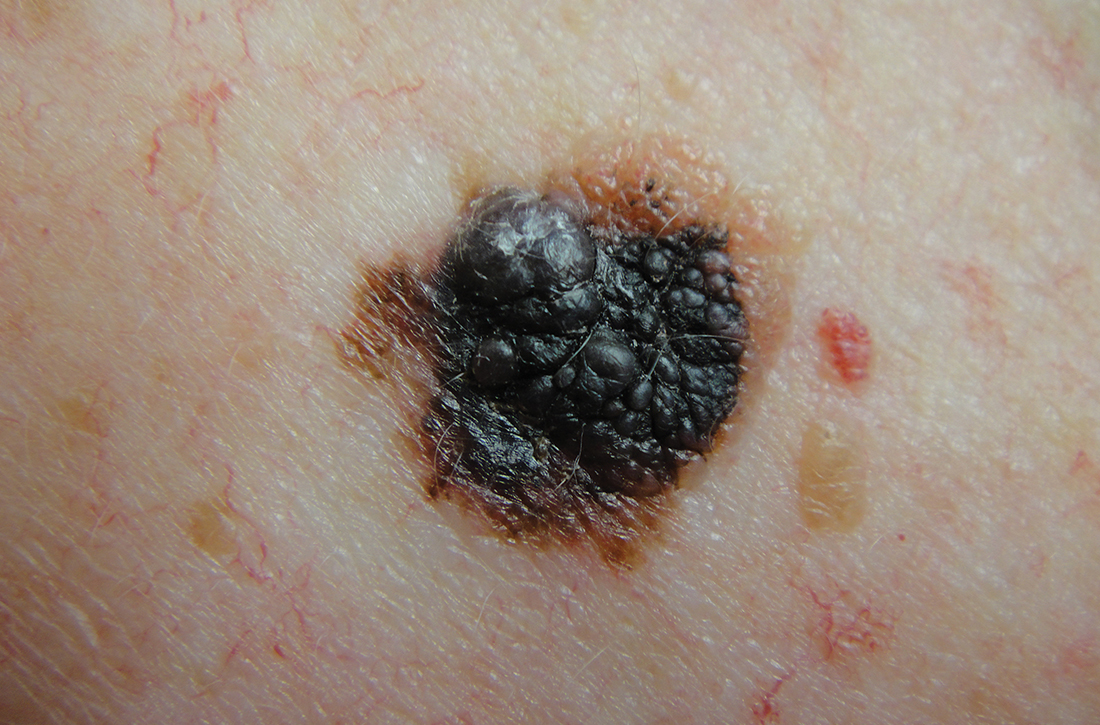

Worrisome physical exam features (FIGURE) are nevus asymmetry, irregular borders, variegated color, and a diameter > 6 mm (the size of a pencil eraser). Inquire as to whether the nevus’ appearance has evolved and if it has bled without trauma. In a patient with multiple nevi, 1 nevus that looks different than the rest (the so-called “ugly duckling”) is concerning. Accuracy of diagnosis is enhanced with dermoscopy. A Cochrane review showed that skilled use of dermoscopy, in addition to inspection with the naked eye, considerably increases the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosing melanoma.4 Yet a 2017 study of 705 US primary care practitioners showed that only 8.3% of them used dermoscopy to evaluate pigmented lesions.5

Several published algorithms and checklists can aid clinicians in identifying lesions suggestive of melanoma—eg, ABCDE, CASH, Menzies method, “chaos and clues,” and 2-step and 3- and 7-point checklists.6-10 A simple 3-step algorithm, the TADA (triage amalgamated dermoscopic algorithm) method is available to novice dermoscopy users.11 Experts in pigmented lesions prefer to use pattern analysis, which requires simultaneously assessing multiple lesion patterns that vary according to body site.12,13

Dermoscopic features suggesting melanoma are atypical pigment networks, pseudopods, radial streaking, irregular dots or globules, blue-whitish veil, and granularity or peppering.14 Appropriate and effective use of dermoscopy requires training.15,16 Available methods for learning dermoscopy include online and in-person courses, mentoring by experienced dermoscopists, books and articles, and free apps and online resources.17

Continue to: Perform a skin biopsy, but do this first

Perform a skin biopsy, but do this first

Skin biopsy is the definitive way to diagnose melanoma. Prior to biopsy, take photographs to document the exact location of the lesion and to ensure that the correct area is removed in wide excision (WE). A complete biopsy should include the full depth and breadth of the lesion to ensure there are clinically negative margins. This can be achieved with an elliptical excision (for larger lesions), punch excision (for small lesions), or saucerization (deep shave with 1- to 2-mm peripheral margins, used for intermediate-size lesions).18 Saucerization is distinctly different from a superficial shave biopsy, which is not recommended for lesions with features of melanoma.19

A decision to perform a biopsy on a part of the lesion (partial biopsy) depends on the size of the lesion and its anatomic location, and is best made in agreement with the patient.

If you are untrained or uncomfortable performing the biopsy, contact a dermatologist immediately. In many communities, such referrals are subject to long delays, which further supports the advisability of family physicians doing their own biopsies after photographing the suspicious lesion. Many resources are available to help family physicians learn to do biopsies proficiently (www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/164358/oncology/biopsies-skin-cancer-detection-dispelling-myths).19

What to communicate to the pathologist. At a minimum, the biopsy request form should include patient age, sex, biopsy type (punch, excisional, or scoop shave), intention (complete or partial sample), exact site of the biopsy with laterality, and clinical details. These details should include the lesion size and clinical description, the suspected diagnosis, and clinical information, such as whether there is a history of bleeding or changing color, size, or symmetry. In standard biopsy specimens, the pathologist is only examining a portion of the lesion. Communicating clearly to the pathologist may lead to a request for deeper or additional sections or special stains.

If the biopsy results do not match the clinical impression, a phone call to the pathologist is warranted. In addition, evaluation by a dermatopathologist may be merited as pathologic diagnosis of melanoma can be quite challenging. Newer molecular tests, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), can assist in the histologic evaluation of complex pigmented lesions.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

You perform an elliptical excisional biopsy on your patient. The biopsy report comes back as a nodular malignant melanoma, Breslow depth 2.5 mm without ulceration, and no evidence of lymphovascular invasion or microsatellitosis. The report states that the biopsy margins appear clear of tumor involvement.

Further evaluation when the biopsy result is positive

Key steps in initial patient care include relaying pathology results to the patient, conducting (as needed) a more extensive evaluation, and obtaining appropriate consultation.

Clearly explain the diagnosis and convey an accurate reading of the pathology report. The vital pieces of information in the biopsy report are the Breslow depth and presence of ulceration, as evidence shows these 2 factors to be important independent predictors of outcome.22,23 Also important are the presence of microsatellitosis (essential for staging purposes), pathologic stage, and the status of the peripheral and deep biopsy margins. Review Breslow depth with the patient as this largely dictates treatment options and prognosis.

Evaluate for possible metastatic disease. Obtain a complete history from every patient with cutaneous melanoma, looking for any positive review of systems as a harbinger of metastatic disease. A full-body skin and lymph node exam is vital, given that melanoma can arise anywhere including on the scalp, in the gluteal cleft, and beneath nails. If the lymph node exam is worrisome, conduct an ultrasound exam, even while referring to specialty care. Treating a patient with melanoma requires a multidisciplinary approach that may include dermatologists, surgeons, and oncologists based on the stage of disease. A challenge for family physicians is knowing which consultation to prioritize and how to counsel the patient to schedule these for the most cost-effective and timely evaluation.

Expedite a dermatology consultation. If the melanoma is deep or appears advanced based on size or palpable lymph nodes, contact the dermatologist immediately by phone to set up a rapid referral. Delays in the definitive management of thick melanomas can negatively affect outcome. Paper, facsimile, or electronic referrals can get lost in the system and are not reliable methods for referring patients for a melanoma consultation. One benefit of the family physician performing the initial biopsy is that a confirmed melanoma diagnosis will almost certainly get an expedited dermatology appointment.

Continue to: Wide excision and sentinel node biopsy

Wide excision and sentinel node biopsy

Wide excision of a primary melanoma is standard practice, with evidence favoring the following surgical margins: 0.5 to 1 cm for melanoma in situ, 1 cm for tumors up to 1 mm in thickness, 1 to 2 cm for tumors > 1 to 2 mm thick, and 2 cm for tumors > 2 mm thick.18 WE is often performed by dermatologists for nonulcerated tumors < 0.8 mm thick (T1a) without adverse features. If trained in cutaneous surgery, you can also choose to excise these thin melanomas in your office. Otherwise refer all patients with biopsy-proven melanoma to dermatologists to perform an adequate WE.

Refer patients who have tumors ≥ 0.8 mm thick to the appropriate surgical specialty (surgical oncology, if available) for consultation on sentinel lymph node biopsy. SLNB, when indicated, should be performed prior to WE of the primary tumor, and whenever possible in the same surgical setting, to maximize lymphatic drainage mapping techniques.18 Medical oncology referral, if needed, is usually made after WE.

SLNB remains the standard for lymph node staging. It is controversial mainly in its use for very thin or very thick lesions. Randomized controlled trials, including the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial,24 have shown no difference in melanoma-specific survival for patients with intermediate-thickness melanomas who had undergone SLNB.24

Many professional organizations consider SLNB to be the most significant prognostic indicator of disease recurrence. With a negative SLNB result, the risk of regional node recurrence is 5% or lower.18,25 In addition, sentinel lymph node status is a critical determinant for systemic adjuvant therapy consideration and clinical trial eligibility. For patients who have primary cutaneous melanoma without clinical lymphadenopathy, an online tool is available for patients to use with their physician in predicting the likelihood of SLNB positivity.26

Recommendations for SLNB, supported by multidisciplinary consensus:18

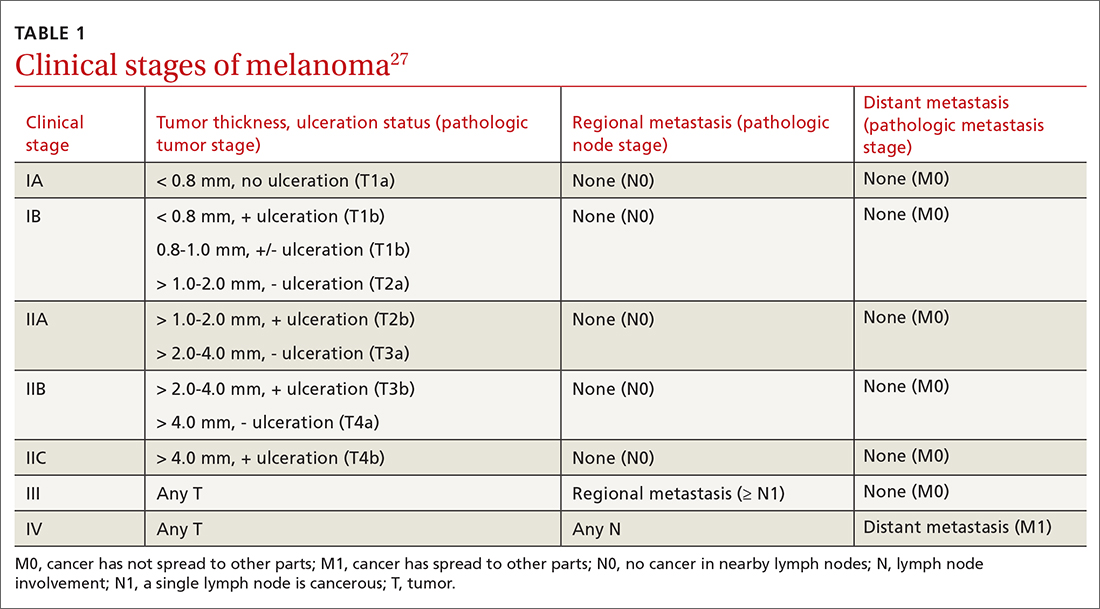

- Do not pursue SLNB for melanoma in situ or most cutaneous melanomas < 0.8 mm without ulceration (T1a). (See TABLE 127)

- Discuss SLNB with patients who have T1a melanoma and additional adverse features: young age, high mitotic rate, lymphovascular invasion, and nevus depth close to 0.8 mm with positive deep biopsy margins.

- Discuss SLNB with patients who have T1b disease (< 0.8 mm with ulceration, or 0.8-1 mm), although rates of SLNB positivity are low.

- Offer SLNB to patients with T2a and higher disease (> 1 mm).18

Continue to: Patients who have...

Patients who have clinical Stage I or II disease (TABLE 127)

Melanoma in women: Considerations to keep in mind

Hormonal influences of pregnancy, lactation, contraception, and menopause introduce special considerations regarding melanoma, which is the most common cancer occurring during pregnancy, accounting for 31% of new malignancies.33 Risk of melanoma lessens, however, for women who first give birth at a younger age or who have had > 5 live births.18,34,35 There is no evidence that nevi darken during pregnancy, although nevi on the breast and abdomen may seem to enlarge due to skin stretching.18 All changing nevi in pregnancy warrant an examination, preferably with dermoscopy, and patients should be offered biopsy if there are any nevus characteristics associated with melanoma.18

The effect of pregnancy on an existing melanoma is not fully understood, but evidence from controlled studies shows no negative effect. Recent working group guidelines advise WE with local anesthesia without delay in pregnant patients.18 Definitive treatment after melanoma diagnosis should take a multidisciplinary approach involving obstetric care coordinated with Dermatology, Surgery, and Medical Oncology.18

Most recommendations on the timing of pregnancy following a melanoma diagnosis have limited evidence. One meta-analysis concluded that pregnancy occurring after successful treatment of melanoma did not change a woman’s prognosis.36 Current guidelines do not recommend delaying future pregnancy if a woman had an early-stage melanoma. For melanomas deemed higher risk, a woman could consider a 2- to 3-year delay in the next planned pregnancy, owing to current data on recurrence rates.18

A systematic review of women who used hormonal contraception or postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) showed no associated increased risk of melanoma.35 An additional randomized trial showed no effect of HRT on melanoma risk.37

Continue to: Systemic melanoma treatment and common adverse effects

Systemic melanoma treatment and common adverse effects

Multiple systemic therapies have been approved for the treatment of advanced or unresectable cutaneous melanomas. While these treatments are managed primarily by Oncology in concert with Dermatology, an awareness of the medications’ common dermatologic toxicities is important for the primary care provider. The 2 broad categories of FDA-approved systemic medications for advanced melanoma are mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors, each having its own set of adverse cutaneous effects.

MAPK pathway–targeting drugs include the B-Raf proto-oncogene serine/threonine-kinase inhibitors (BRAFIs) vemurafenib and dabrafenib, and the MAPK inhibitors (MEKIs) trametinib and cobimetinib. The most common adverse skin effects in MAPK pathway–targeting drugs are severe ultraviolet photosensitivity, cutaneous epidermal neoplasms (particularly squamous cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma-type), thick actinic keratosis, wart-like keratosis, painful palmoplantar keratosis, and dry skin.38 These effects are most commonly seen with BRAFI monotherapy and can be abated with the addition of a MEKI. MEKI therapy can cause acneiform eruptions and paronychia.39 Additional adverse effects include diarrhea, pyrexia, arthralgias, and fatigue for BRAFIs and diarrhea, fatigue, and peripheral edema for MEKIs.40

Immune checkpoint inhibitors include anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), anti-PD-1 (pembrolizumab and nivolumab), and anti-PDL-1 (atezolizumab). Adverse skin effects include morbilliform rash with or without an associated itch, itch with or without an associated rash, vitiligo, and lichenoid skin rashes. PD-1 and PDL-1 inhibitors have been associated with flares or unmasking of atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, sarcoidosis, and autoimmune bullous disease.18 Diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, elevated liver enzymes, hypophysitis, and thyroiditis are some of the more common noncutaneous adverse effects reported with CTLA-4 inhibitors, while fatigue, diarrhea, nausea, pneumonitis, and thyroid disease are seen with anti-PD-1/PDL-1 therapy.3

A look at the prognosis

For patients diagnosed with primary cutaneous melanoma between 2011 and 2017, the 5-year survival rate for localized disease (Stages I-II) was 99%.1 For regional (Stage III) and distant (Stage IV) disease, the 5-year survival rates were 68% and 30%, respectively.1 With the advent of adjuvant systemic therapy, 5-year overall survival rates for metastatic melanoma have markedly improved from < 10% to up to 40% to 50%.41 The 3-year survival rate for patients with high tumor burden, brain metastasis, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase remains at < 10%.42 Relative survival decreases with increased age, although survival is higher in women than in men.43 Risk of melanoma recurrence after surgical excision is high in patients with stage IIB, IIC, III and IV (resectable) disease. The most important risk factor for recurrence is primary tumor thickness.44 The most common site of first recurrence in stage I-II disease is regional lymph node metastasis (42.8%), closely followed by distant metastasis (37.6%).44

Long-term follow-up and surveillance

Recommendations for long-term care of patients with melanoma have evolved with advances in treatment, prognostication, and imaging. Caring for these patients requires a multidisciplinary approach wherein the family physician provides frontline care and team coordination. Since most recurrences are discovered by the patient or the patient’s family, patient education and self-examination are the cost-effective foundation for recurrence screening. In a trial of patients and partners, a 30-minute structured session on skin examination followed by physician reminders every 4 months increased the detection of melanoma recurrence without significant increases in patient visits.45

Continue to: Patient education should include sun safety...

Patient education should include sun safety (wearing sun-protective clothing, using broad-spectrum sunscreen, and avoiding sun exposure during peak times of the day). The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) says the level of evidence is insufficient to support routine skin cancer screening in adults.46 However, the USPSTF recommends discussing efforts to minimize UV radiation exposure to prevent skin cancer in fair-skinned individuals 10 to 24 years of age.

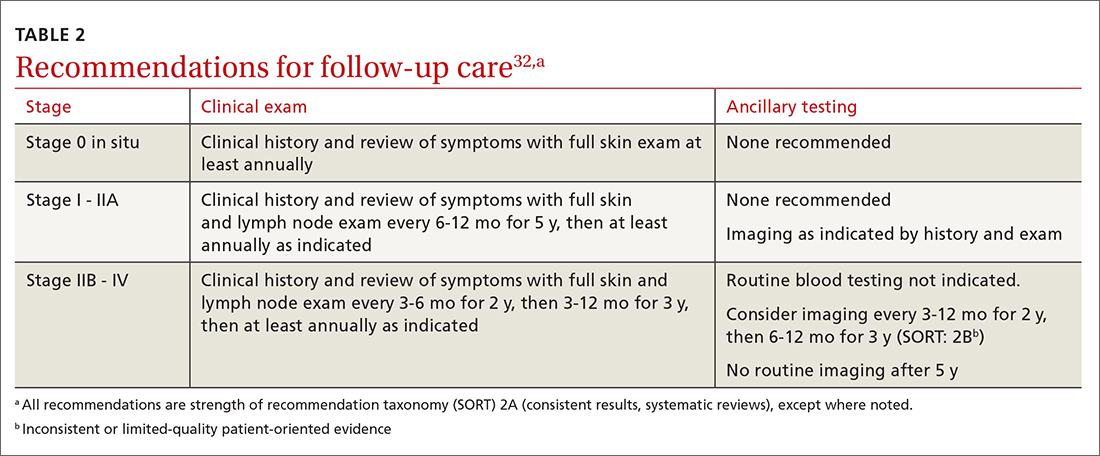

Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines have outlined the follow-up frequency for all melanoma patients. TABLE 232 outlines those recommendations in addition to self-examination and patient education.

Melanoma epidemic or overdiagnosis?

Over the past 2 decades, a marked rise in the incidence of melanoma has been reported in developed countries worldwide, although melanoma mortality rates have not increased as rapidly, with melanoma-specific survival stable in most groups.47-50 Due to conflicting evidence, significant disagreement exists as to whether this is an actual epidemic caused by a true rise in disease burden or is merely an artifact stemming from overdiagnosis.47

Evidence supporting a true melanoma epidemic includes population-based studies demonstrating greater UV radiation–induced carcinogenesis (from the sun and tanning bed use), a larger aging population, and increased incidence regardless of socioeconomic status.47 Those challenging the validity of an epidemic instead attribute the rising incidence to early-detection public awareness campaigns, expanded screenings, improved diagnostic modalities, and increased biopsies. They also credit lower pathologic thresholds that help identify thinner tumors with little to no metastatic potential.48 Additionally, multiple studies report an increased incidence in melanomas of all histologic subtypes and thicknesses, not just thinner, more curable tumors.49,51,52 Although increased screening and biopsies are effective, they alone cannot account for the sharp rise in melanoma cases.47 This “melanoma paradox” of increasing incidence without a parallel increase in mortality remains unsettled.47

CASE

Your patient had Stage IIA disease and a WE was performed with 1-cm margins. Ultrasound of the axilla identified an enlarged node, which was removed and found not to be diseased. He has now returned to have you look at another lesion identified by his spouse. His review of symptoms is negative. His initial melanoma was removed 2 years earlier, and his last dermatology skin exam was 5 months prior. You look at the lesion using a dermatoscope and do not note any worrisome features. You recommend that the patient photograph the area for reexamination and follow-up with his dermatologist next month for a 6-month follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jessica Servey, MD, 4301 Jones Bridge Road, Bethesda, MD 20814; [email protected]

1. NIH. Cancer stat facts: melanoma of the skin. 2018. Accessed May 13, 2021. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html

2. Watts CG, Dieng M, Morton RL, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for identification, screening and follow-up of individuals at high risk of primary cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:33-47.

3. Schadendorf D, van Akkooi ACJ, Berking C, et al. Melanoma. Lancet. 2018;392:971-984.

4. Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Chuchu N, et al. Dermoscopy, with and without visual inspection, for diagnosing melanoma in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018(12):CD011902.

5. Morris JB, Alfonso SV, Hernandez N, et al. Examining the factors associated with past and present dermoscopy use among family physicians. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:63-70.

6. Henning JS, Dusza SW, Wang SQ, et al. The CASH (color, architecture, symmetry, and homogeneity) algorithm for dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:45-52.

7. Rosendahl C, Cameron A, McColl I, et al. Dermatoscopy in routine practice — “chaos and clues”. Aust Fam Physician. 2012;41:482-487.

8. Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Zalaudek I, et al. Three-point checklist of dermoscopy: a new screening method for early detection of melanoma. Dermatology. 2004;208:27-31.

9. Argenziano G, Fabbrocini G, Carli P, et al. Epiluminescence microscopy for the diagnosis of doubtful melanocytic skin lesions. Comparison of the ABCD rule of dermatoscopy and a new 7-point checklist based on pattern analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1563-1570.

10. Marghoob AA, Usatine RP, Jaimes N. Dermoscopy for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:441-450.

11. Rogers T, Marino ML, Dusza SW, et al. A clinical aid for detecting skin cancer: the Triage Amalgamated Dermoscopic Algorithm (TADA). J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29:694-701.

12. Argenziano G, Soyer HP, Chimenti S, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions: results of a consensus meeting via the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:679-93.

13. Carli P, Quercioli E, Sestini S, et al. Pattern analysis, not simplified algorithms, is the most reliable method for teaching dermoscopy for melanoma diagnosis to residents in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:981-984.

14. Yélamos O, Braun RP, Liopyris K, et al. Usefulness of dermoscopy to improve the clinical and histopathologic diagnosis of skin cancers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:365-377.

15. Westerhoff K, McCarthy WH, Menzies SW. Increase in the sensitivity for melanoma diagnosis by primary care physicians using skin surface microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1016-1020.

16. Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

17. Usatine RP, Shama LK, Marghoob AA, et al. Dermoscopy in family medicine: a primer. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:E1-E11.

18. Swetter SM, Tsao H, Bichakjian CK, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:208-250.

19. Seiverling EV, Ahrns HT, Bacik LC, et al. Biopsies for skin cancer detection: dispelling the myths. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:270-274.

20. Martin RCG, Scoggins CR, Ross MI, et al. Is incisional biopsy of melanoma harmful? Am J Surg. 2005;190:913-917.

21. Mir M, Chan CS, Khan F, et al. The rate of melanoma transection with various biopsy techniques and the influence of tumor transection on patient survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:452-458.

22. Breslow A. Thickness, cross-sectional areas and depth of invasion in the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg. 1970;172:902-908

23. Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th ed cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:472-492.

24. Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:599-609.

25. Valsecchi ME, Silbermins D, de Rosa N, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with melanoma: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1479-1487.

26. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Risk of sentinel lymph node metastasis nomogram. Accessed May 13, 2021. www.mskcc.org/nomograms/melanoma/sentinel_lymph_node_metastasis

27. Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer International Publishing; 2017:563-581.

28. Xing Y, Bronstein Y, Ross MI, et al. Contemporary diagnostic imaging modalities for the staging and surveillance of melanoma patients: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:129-142.

29. Tsao H, Feldman M, Fullerton JE, et al. Early detection of asymptomatic pulmonary melanoma metastases by routine chest radiographs is not associated with improved survival. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:67-70.

30. Wang TS, Johnson TM, Cascade PN, et al. Evaluation of staging chest radiographs and serum lactate dehydrogenase for localized melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:399-405.

31. Yancovitz M, Finelt N, Warycha MA, et al. Role of radiologic imaging at the time of initial diagnosis of stage T1b-T3b melanoma. Cancer. 2007; 110:1107-1114.

32. Swetter SM, Thompson JA, Albertini MR, et al. NCCN Guidelines: cutaneous melanoma, version 4.2020. Accessed June 7, 2021. http://medi-guide.meditool.cn/ymtpdf/ACC90A18-6CDF-9443-BF3F-E29394D495E8.pdf

33. Stensheim H, Møller B, van Dijk T, et al. Cause-specific survival for women diagnosed with cancer during pregnancy or lactation: a registry-based cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:45-51.

34. Lens MB, Rosdahl I, Ahlbom A, et al. Effect of pregnancy on survival in women with cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4369-4375.

35. Gandini S, Iodice S, Koomen E, et al. Hormonal and reproductive factors in relation to melanoma in women: current review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2607-2617.

36. Byrom L, Olsen CM, Knight L, et al. Does pregnancy after a diagnosis of melanoma affect prognosis? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:875-882.

37. Tang JY, Spaunhurst KM, Chlebowski RT, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and risks of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers: women’s health initiative randomized trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1469-1475.

38. Carlos G, Anforth R, Clements A, et al. Cutaneous toxic effects of BRAF inhibitors alone and in combination with MEK inhibitors for metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1103-1109.

39. Macdonald JB, Macdonald B, Golitz LE, et al. Cutaneous adverse effects of targeted therapies: part I: inhibitors of the cellular membrane. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:203-218.

40. Welsh SJ, Corrie PG. Management of BRAF and MEK inhibitor toxicities in patients with metastatic melanoma. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2015;7:122-136.

41. Kandolf Sekulovic L, Peris K, Hauschild A, et al. More than 5000 patients with metastatic melanoma in Europe per year do not have access to recommended first-line innovative treatments. Eur J Cancer. 2017;75:313-322.

42. Long GV, Grob JJ, Nathan P, et al. Factors predictive of response, disease progression, and overall survival after dabrafenib and trametinib combination treatment: a pooled analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1743-1754.

43. Trends in incidence and survival in patients with melanoma, 1974-2013. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:1396-1414.

44. Lyth J, Falk M, Maroti M, et al. Prognostic risk factors of first recurrence in patients with primary stages I–II cutaneous malignant melanoma – from the population‐based Swedish melanoma register. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1468-1474.

45. Robinson JK, Wayne JD, Martini MC, et al. Early detection of new melanomas by patients with melanoma and their partners using a structured skin self-examination skills training intervention: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:979-985.

Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

47. Gardner LJ, Strunck JL, Wu YP, et al. Current controversies in early-stage melanoma: questions on incidence, screening, and histologic regression. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1-12.

48. Wei EX, Qureshi AA, Han J, et al. Trends in the diagnosis and clinical features of melanoma in situ (MIS) in US men and women: a prospective, observational study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:698-705.

49. Linos E, Swetter SM, Cockburn MG, et al. Increasing burden of melanoma in the United States. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1666-1674.

50. Curchin DJ, Forward E, Dickison P, et al. The acceleration of melanoma in situ: a population-based study of melanoma incidence trends from Victoria, Australia, 1985-2015. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1791-1793.

51. Dennis LK. Analysis of the melanoma epidemic, both apparent and real: data from the 1973 through 1994 surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program registry. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:275-280.

52. Jemal A, Saraiya M, Patel P, et al. Recent trends in cutaneous melanoma incidence and death rates in the United States, 1992-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:S17-S25.

CASE

A 48-year-old man comes to your clinic with a dark nevus on his right upper arm that appeared 2 months earlier. He says that the lesion has continued to grow and has bled (he thought because he initially picked at it). On exam, there is a 7-mm brown papule with 2 black dots and slightly asymmetric borders.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Melanoma is the fifth leading cause of new cancer cases annually, with > 96,000 new cases in 2019.1 Overall, melanoma is more common in men and in Whites, with 48% diagnosed in people ages 55 to 74.1 The past 2 decades have seen numerous developments in the diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance of melanoma. This article covers recommendations, controversies, and issues that require future study. It does not cover uveal or mucosal melanoma.

Evaluating a patient with a new or changing nevus

Known risk factors for melanoma include a changing nevus, indoor tanning, older age, many melanocytic nevi, history of a dysplastic nevus or of blistering sunburns during teen years, red or blonde hair, large congenital nevus, Fitzpatrick skin type I or II, high socioeconomic status, personal or family history of melanoma, and intermittent high-intensity sun exposure.2-3 Presence of 1 or more of these risk factors should lower the threshold for biopsy.

Worrisome physical exam features (FIGURE) are nevus asymmetry, irregular borders, variegated color, and a diameter > 6 mm (the size of a pencil eraser). Inquire as to whether the nevus’ appearance has evolved and if it has bled without trauma. In a patient with multiple nevi, 1 nevus that looks different than the rest (the so-called “ugly duckling”) is concerning. Accuracy of diagnosis is enhanced with dermoscopy. A Cochrane review showed that skilled use of dermoscopy, in addition to inspection with the naked eye, considerably increases the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosing melanoma.4 Yet a 2017 study of 705 US primary care practitioners showed that only 8.3% of them used dermoscopy to evaluate pigmented lesions.5

Several published algorithms and checklists can aid clinicians in identifying lesions suggestive of melanoma—eg, ABCDE, CASH, Menzies method, “chaos and clues,” and 2-step and 3- and 7-point checklists.6-10 A simple 3-step algorithm, the TADA (triage amalgamated dermoscopic algorithm) method is available to novice dermoscopy users.11 Experts in pigmented lesions prefer to use pattern analysis, which requires simultaneously assessing multiple lesion patterns that vary according to body site.12,13

Dermoscopic features suggesting melanoma are atypical pigment networks, pseudopods, radial streaking, irregular dots or globules, blue-whitish veil, and granularity or peppering.14 Appropriate and effective use of dermoscopy requires training.15,16 Available methods for learning dermoscopy include online and in-person courses, mentoring by experienced dermoscopists, books and articles, and free apps and online resources.17

Continue to: Perform a skin biopsy, but do this first

Perform a skin biopsy, but do this first

Skin biopsy is the definitive way to diagnose melanoma. Prior to biopsy, take photographs to document the exact location of the lesion and to ensure that the correct area is removed in wide excision (WE). A complete biopsy should include the full depth and breadth of the lesion to ensure there are clinically negative margins. This can be achieved with an elliptical excision (for larger lesions), punch excision (for small lesions), or saucerization (deep shave with 1- to 2-mm peripheral margins, used for intermediate-size lesions).18 Saucerization is distinctly different from a superficial shave biopsy, which is not recommended for lesions with features of melanoma.19

A decision to perform a biopsy on a part of the lesion (partial biopsy) depends on the size of the lesion and its anatomic location, and is best made in agreement with the patient.

If you are untrained or uncomfortable performing the biopsy, contact a dermatologist immediately. In many communities, such referrals are subject to long delays, which further supports the advisability of family physicians doing their own biopsies after photographing the suspicious lesion. Many resources are available to help family physicians learn to do biopsies proficiently (www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/164358/oncology/biopsies-skin-cancer-detection-dispelling-myths).19

What to communicate to the pathologist. At a minimum, the biopsy request form should include patient age, sex, biopsy type (punch, excisional, or scoop shave), intention (complete or partial sample), exact site of the biopsy with laterality, and clinical details. These details should include the lesion size and clinical description, the suspected diagnosis, and clinical information, such as whether there is a history of bleeding or changing color, size, or symmetry. In standard biopsy specimens, the pathologist is only examining a portion of the lesion. Communicating clearly to the pathologist may lead to a request for deeper or additional sections or special stains.

If the biopsy results do not match the clinical impression, a phone call to the pathologist is warranted. In addition, evaluation by a dermatopathologist may be merited as pathologic diagnosis of melanoma can be quite challenging. Newer molecular tests, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), can assist in the histologic evaluation of complex pigmented lesions.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

You perform an elliptical excisional biopsy on your patient. The biopsy report comes back as a nodular malignant melanoma, Breslow depth 2.5 mm without ulceration, and no evidence of lymphovascular invasion or microsatellitosis. The report states that the biopsy margins appear clear of tumor involvement.

Further evaluation when the biopsy result is positive

Key steps in initial patient care include relaying pathology results to the patient, conducting (as needed) a more extensive evaluation, and obtaining appropriate consultation.

Clearly explain the diagnosis and convey an accurate reading of the pathology report. The vital pieces of information in the biopsy report are the Breslow depth and presence of ulceration, as evidence shows these 2 factors to be important independent predictors of outcome.22,23 Also important are the presence of microsatellitosis (essential for staging purposes), pathologic stage, and the status of the peripheral and deep biopsy margins. Review Breslow depth with the patient as this largely dictates treatment options and prognosis.

Evaluate for possible metastatic disease. Obtain a complete history from every patient with cutaneous melanoma, looking for any positive review of systems as a harbinger of metastatic disease. A full-body skin and lymph node exam is vital, given that melanoma can arise anywhere including on the scalp, in the gluteal cleft, and beneath nails. If the lymph node exam is worrisome, conduct an ultrasound exam, even while referring to specialty care. Treating a patient with melanoma requires a multidisciplinary approach that may include dermatologists, surgeons, and oncologists based on the stage of disease. A challenge for family physicians is knowing which consultation to prioritize and how to counsel the patient to schedule these for the most cost-effective and timely evaluation.

Expedite a dermatology consultation. If the melanoma is deep or appears advanced based on size or palpable lymph nodes, contact the dermatologist immediately by phone to set up a rapid referral. Delays in the definitive management of thick melanomas can negatively affect outcome. Paper, facsimile, or electronic referrals can get lost in the system and are not reliable methods for referring patients for a melanoma consultation. One benefit of the family physician performing the initial biopsy is that a confirmed melanoma diagnosis will almost certainly get an expedited dermatology appointment.

Continue to: Wide excision and sentinel node biopsy

Wide excision and sentinel node biopsy

Wide excision of a primary melanoma is standard practice, with evidence favoring the following surgical margins: 0.5 to 1 cm for melanoma in situ, 1 cm for tumors up to 1 mm in thickness, 1 to 2 cm for tumors > 1 to 2 mm thick, and 2 cm for tumors > 2 mm thick.18 WE is often performed by dermatologists for nonulcerated tumors < 0.8 mm thick (T1a) without adverse features. If trained in cutaneous surgery, you can also choose to excise these thin melanomas in your office. Otherwise refer all patients with biopsy-proven melanoma to dermatologists to perform an adequate WE.

Refer patients who have tumors ≥ 0.8 mm thick to the appropriate surgical specialty (surgical oncology, if available) for consultation on sentinel lymph node biopsy. SLNB, when indicated, should be performed prior to WE of the primary tumor, and whenever possible in the same surgical setting, to maximize lymphatic drainage mapping techniques.18 Medical oncology referral, if needed, is usually made after WE.

SLNB remains the standard for lymph node staging. It is controversial mainly in its use for very thin or very thick lesions. Randomized controlled trials, including the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial,24 have shown no difference in melanoma-specific survival for patients with intermediate-thickness melanomas who had undergone SLNB.24

Many professional organizations consider SLNB to be the most significant prognostic indicator of disease recurrence. With a negative SLNB result, the risk of regional node recurrence is 5% or lower.18,25 In addition, sentinel lymph node status is a critical determinant for systemic adjuvant therapy consideration and clinical trial eligibility. For patients who have primary cutaneous melanoma without clinical lymphadenopathy, an online tool is available for patients to use with their physician in predicting the likelihood of SLNB positivity.26

Recommendations for SLNB, supported by multidisciplinary consensus:18

- Do not pursue SLNB for melanoma in situ or most cutaneous melanomas < 0.8 mm without ulceration (T1a). (See TABLE 127)

- Discuss SLNB with patients who have T1a melanoma and additional adverse features: young age, high mitotic rate, lymphovascular invasion, and nevus depth close to 0.8 mm with positive deep biopsy margins.

- Discuss SLNB with patients who have T1b disease (< 0.8 mm with ulceration, or 0.8-1 mm), although rates of SLNB positivity are low.

- Offer SLNB to patients with T2a and higher disease (> 1 mm).18

Continue to: Patients who have...

Patients who have clinical Stage I or II disease (TABLE 127)

Melanoma in women: Considerations to keep in mind

Hormonal influences of pregnancy, lactation, contraception, and menopause introduce special considerations regarding melanoma, which is the most common cancer occurring during pregnancy, accounting for 31% of new malignancies.33 Risk of melanoma lessens, however, for women who first give birth at a younger age or who have had > 5 live births.18,34,35 There is no evidence that nevi darken during pregnancy, although nevi on the breast and abdomen may seem to enlarge due to skin stretching.18 All changing nevi in pregnancy warrant an examination, preferably with dermoscopy, and patients should be offered biopsy if there are any nevus characteristics associated with melanoma.18

The effect of pregnancy on an existing melanoma is not fully understood, but evidence from controlled studies shows no negative effect. Recent working group guidelines advise WE with local anesthesia without delay in pregnant patients.18 Definitive treatment after melanoma diagnosis should take a multidisciplinary approach involving obstetric care coordinated with Dermatology, Surgery, and Medical Oncology.18

Most recommendations on the timing of pregnancy following a melanoma diagnosis have limited evidence. One meta-analysis concluded that pregnancy occurring after successful treatment of melanoma did not change a woman’s prognosis.36 Current guidelines do not recommend delaying future pregnancy if a woman had an early-stage melanoma. For melanomas deemed higher risk, a woman could consider a 2- to 3-year delay in the next planned pregnancy, owing to current data on recurrence rates.18

A systematic review of women who used hormonal contraception or postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) showed no associated increased risk of melanoma.35 An additional randomized trial showed no effect of HRT on melanoma risk.37

Continue to: Systemic melanoma treatment and common adverse effects

Systemic melanoma treatment and common adverse effects

Multiple systemic therapies have been approved for the treatment of advanced or unresectable cutaneous melanomas. While these treatments are managed primarily by Oncology in concert with Dermatology, an awareness of the medications’ common dermatologic toxicities is important for the primary care provider. The 2 broad categories of FDA-approved systemic medications for advanced melanoma are mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors, each having its own set of adverse cutaneous effects.

MAPK pathway–targeting drugs include the B-Raf proto-oncogene serine/threonine-kinase inhibitors (BRAFIs) vemurafenib and dabrafenib, and the MAPK inhibitors (MEKIs) trametinib and cobimetinib. The most common adverse skin effects in MAPK pathway–targeting drugs are severe ultraviolet photosensitivity, cutaneous epidermal neoplasms (particularly squamous cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma-type), thick actinic keratosis, wart-like keratosis, painful palmoplantar keratosis, and dry skin.38 These effects are most commonly seen with BRAFI monotherapy and can be abated with the addition of a MEKI. MEKI therapy can cause acneiform eruptions and paronychia.39 Additional adverse effects include diarrhea, pyrexia, arthralgias, and fatigue for BRAFIs and diarrhea, fatigue, and peripheral edema for MEKIs.40

Immune checkpoint inhibitors include anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), anti-PD-1 (pembrolizumab and nivolumab), and anti-PDL-1 (atezolizumab). Adverse skin effects include morbilliform rash with or without an associated itch, itch with or without an associated rash, vitiligo, and lichenoid skin rashes. PD-1 and PDL-1 inhibitors have been associated with flares or unmasking of atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, sarcoidosis, and autoimmune bullous disease.18 Diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, elevated liver enzymes, hypophysitis, and thyroiditis are some of the more common noncutaneous adverse effects reported with CTLA-4 inhibitors, while fatigue, diarrhea, nausea, pneumonitis, and thyroid disease are seen with anti-PD-1/PDL-1 therapy.3

A look at the prognosis

For patients diagnosed with primary cutaneous melanoma between 2011 and 2017, the 5-year survival rate for localized disease (Stages I-II) was 99%.1 For regional (Stage III) and distant (Stage IV) disease, the 5-year survival rates were 68% and 30%, respectively.1 With the advent of adjuvant systemic therapy, 5-year overall survival rates for metastatic melanoma have markedly improved from < 10% to up to 40% to 50%.41 The 3-year survival rate for patients with high tumor burden, brain metastasis, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase remains at < 10%.42 Relative survival decreases with increased age, although survival is higher in women than in men.43 Risk of melanoma recurrence after surgical excision is high in patients with stage IIB, IIC, III and IV (resectable) disease. The most important risk factor for recurrence is primary tumor thickness.44 The most common site of first recurrence in stage I-II disease is regional lymph node metastasis (42.8%), closely followed by distant metastasis (37.6%).44

Long-term follow-up and surveillance

Recommendations for long-term care of patients with melanoma have evolved with advances in treatment, prognostication, and imaging. Caring for these patients requires a multidisciplinary approach wherein the family physician provides frontline care and team coordination. Since most recurrences are discovered by the patient or the patient’s family, patient education and self-examination are the cost-effective foundation for recurrence screening. In a trial of patients and partners, a 30-minute structured session on skin examination followed by physician reminders every 4 months increased the detection of melanoma recurrence without significant increases in patient visits.45

Continue to: Patient education should include sun safety...

Patient education should include sun safety (wearing sun-protective clothing, using broad-spectrum sunscreen, and avoiding sun exposure during peak times of the day). The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) says the level of evidence is insufficient to support routine skin cancer screening in adults.46 However, the USPSTF recommends discussing efforts to minimize UV radiation exposure to prevent skin cancer in fair-skinned individuals 10 to 24 years of age.

Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines have outlined the follow-up frequency for all melanoma patients. TABLE 232 outlines those recommendations in addition to self-examination and patient education.

Melanoma epidemic or overdiagnosis?

Over the past 2 decades, a marked rise in the incidence of melanoma has been reported in developed countries worldwide, although melanoma mortality rates have not increased as rapidly, with melanoma-specific survival stable in most groups.47-50 Due to conflicting evidence, significant disagreement exists as to whether this is an actual epidemic caused by a true rise in disease burden or is merely an artifact stemming from overdiagnosis.47

Evidence supporting a true melanoma epidemic includes population-based studies demonstrating greater UV radiation–induced carcinogenesis (from the sun and tanning bed use), a larger aging population, and increased incidence regardless of socioeconomic status.47 Those challenging the validity of an epidemic instead attribute the rising incidence to early-detection public awareness campaigns, expanded screenings, improved diagnostic modalities, and increased biopsies. They also credit lower pathologic thresholds that help identify thinner tumors with little to no metastatic potential.48 Additionally, multiple studies report an increased incidence in melanomas of all histologic subtypes and thicknesses, not just thinner, more curable tumors.49,51,52 Although increased screening and biopsies are effective, they alone cannot account for the sharp rise in melanoma cases.47 This “melanoma paradox” of increasing incidence without a parallel increase in mortality remains unsettled.47

CASE

Your patient had Stage IIA disease and a WE was performed with 1-cm margins. Ultrasound of the axilla identified an enlarged node, which was removed and found not to be diseased. He has now returned to have you look at another lesion identified by his spouse. His review of symptoms is negative. His initial melanoma was removed 2 years earlier, and his last dermatology skin exam was 5 months prior. You look at the lesion using a dermatoscope and do not note any worrisome features. You recommend that the patient photograph the area for reexamination and follow-up with his dermatologist next month for a 6-month follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jessica Servey, MD, 4301 Jones Bridge Road, Bethesda, MD 20814; [email protected]

CASE

A 48-year-old man comes to your clinic with a dark nevus on his right upper arm that appeared 2 months earlier. He says that the lesion has continued to grow and has bled (he thought because he initially picked at it). On exam, there is a 7-mm brown papule with 2 black dots and slightly asymmetric borders.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Melanoma is the fifth leading cause of new cancer cases annually, with > 96,000 new cases in 2019.1 Overall, melanoma is more common in men and in Whites, with 48% diagnosed in people ages 55 to 74.1 The past 2 decades have seen numerous developments in the diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance of melanoma. This article covers recommendations, controversies, and issues that require future study. It does not cover uveal or mucosal melanoma.

Evaluating a patient with a new or changing nevus

Known risk factors for melanoma include a changing nevus, indoor tanning, older age, many melanocytic nevi, history of a dysplastic nevus or of blistering sunburns during teen years, red or blonde hair, large congenital nevus, Fitzpatrick skin type I or II, high socioeconomic status, personal or family history of melanoma, and intermittent high-intensity sun exposure.2-3 Presence of 1 or more of these risk factors should lower the threshold for biopsy.

Worrisome physical exam features (FIGURE) are nevus asymmetry, irregular borders, variegated color, and a diameter > 6 mm (the size of a pencil eraser). Inquire as to whether the nevus’ appearance has evolved and if it has bled without trauma. In a patient with multiple nevi, 1 nevus that looks different than the rest (the so-called “ugly duckling”) is concerning. Accuracy of diagnosis is enhanced with dermoscopy. A Cochrane review showed that skilled use of dermoscopy, in addition to inspection with the naked eye, considerably increases the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosing melanoma.4 Yet a 2017 study of 705 US primary care practitioners showed that only 8.3% of them used dermoscopy to evaluate pigmented lesions.5

Several published algorithms and checklists can aid clinicians in identifying lesions suggestive of melanoma—eg, ABCDE, CASH, Menzies method, “chaos and clues,” and 2-step and 3- and 7-point checklists.6-10 A simple 3-step algorithm, the TADA (triage amalgamated dermoscopic algorithm) method is available to novice dermoscopy users.11 Experts in pigmented lesions prefer to use pattern analysis, which requires simultaneously assessing multiple lesion patterns that vary according to body site.12,13

Dermoscopic features suggesting melanoma are atypical pigment networks, pseudopods, radial streaking, irregular dots or globules, blue-whitish veil, and granularity or peppering.14 Appropriate and effective use of dermoscopy requires training.15,16 Available methods for learning dermoscopy include online and in-person courses, mentoring by experienced dermoscopists, books and articles, and free apps and online resources.17

Continue to: Perform a skin biopsy, but do this first

Perform a skin biopsy, but do this first

Skin biopsy is the definitive way to diagnose melanoma. Prior to biopsy, take photographs to document the exact location of the lesion and to ensure that the correct area is removed in wide excision (WE). A complete biopsy should include the full depth and breadth of the lesion to ensure there are clinically negative margins. This can be achieved with an elliptical excision (for larger lesions), punch excision (for small lesions), or saucerization (deep shave with 1- to 2-mm peripheral margins, used for intermediate-size lesions).18 Saucerization is distinctly different from a superficial shave biopsy, which is not recommended for lesions with features of melanoma.19

A decision to perform a biopsy on a part of the lesion (partial biopsy) depends on the size of the lesion and its anatomic location, and is best made in agreement with the patient.

If you are untrained or uncomfortable performing the biopsy, contact a dermatologist immediately. In many communities, such referrals are subject to long delays, which further supports the advisability of family physicians doing their own biopsies after photographing the suspicious lesion. Many resources are available to help family physicians learn to do biopsies proficiently (www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/164358/oncology/biopsies-skin-cancer-detection-dispelling-myths).19

What to communicate to the pathologist. At a minimum, the biopsy request form should include patient age, sex, biopsy type (punch, excisional, or scoop shave), intention (complete or partial sample), exact site of the biopsy with laterality, and clinical details. These details should include the lesion size and clinical description, the suspected diagnosis, and clinical information, such as whether there is a history of bleeding or changing color, size, or symmetry. In standard biopsy specimens, the pathologist is only examining a portion of the lesion. Communicating clearly to the pathologist may lead to a request for deeper or additional sections or special stains.

If the biopsy results do not match the clinical impression, a phone call to the pathologist is warranted. In addition, evaluation by a dermatopathologist may be merited as pathologic diagnosis of melanoma can be quite challenging. Newer molecular tests, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), can assist in the histologic evaluation of complex pigmented lesions.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

You perform an elliptical excisional biopsy on your patient. The biopsy report comes back as a nodular malignant melanoma, Breslow depth 2.5 mm without ulceration, and no evidence of lymphovascular invasion or microsatellitosis. The report states that the biopsy margins appear clear of tumor involvement.

Further evaluation when the biopsy result is positive

Key steps in initial patient care include relaying pathology results to the patient, conducting (as needed) a more extensive evaluation, and obtaining appropriate consultation.

Clearly explain the diagnosis and convey an accurate reading of the pathology report. The vital pieces of information in the biopsy report are the Breslow depth and presence of ulceration, as evidence shows these 2 factors to be important independent predictors of outcome.22,23 Also important are the presence of microsatellitosis (essential for staging purposes), pathologic stage, and the status of the peripheral and deep biopsy margins. Review Breslow depth with the patient as this largely dictates treatment options and prognosis.

Evaluate for possible metastatic disease. Obtain a complete history from every patient with cutaneous melanoma, looking for any positive review of systems as a harbinger of metastatic disease. A full-body skin and lymph node exam is vital, given that melanoma can arise anywhere including on the scalp, in the gluteal cleft, and beneath nails. If the lymph node exam is worrisome, conduct an ultrasound exam, even while referring to specialty care. Treating a patient with melanoma requires a multidisciplinary approach that may include dermatologists, surgeons, and oncologists based on the stage of disease. A challenge for family physicians is knowing which consultation to prioritize and how to counsel the patient to schedule these for the most cost-effective and timely evaluation.

Expedite a dermatology consultation. If the melanoma is deep or appears advanced based on size or palpable lymph nodes, contact the dermatologist immediately by phone to set up a rapid referral. Delays in the definitive management of thick melanomas can negatively affect outcome. Paper, facsimile, or electronic referrals can get lost in the system and are not reliable methods for referring patients for a melanoma consultation. One benefit of the family physician performing the initial biopsy is that a confirmed melanoma diagnosis will almost certainly get an expedited dermatology appointment.

Continue to: Wide excision and sentinel node biopsy

Wide excision and sentinel node biopsy

Wide excision of a primary melanoma is standard practice, with evidence favoring the following surgical margins: 0.5 to 1 cm for melanoma in situ, 1 cm for tumors up to 1 mm in thickness, 1 to 2 cm for tumors > 1 to 2 mm thick, and 2 cm for tumors > 2 mm thick.18 WE is often performed by dermatologists for nonulcerated tumors < 0.8 mm thick (T1a) without adverse features. If trained in cutaneous surgery, you can also choose to excise these thin melanomas in your office. Otherwise refer all patients with biopsy-proven melanoma to dermatologists to perform an adequate WE.

Refer patients who have tumors ≥ 0.8 mm thick to the appropriate surgical specialty (surgical oncology, if available) for consultation on sentinel lymph node biopsy. SLNB, when indicated, should be performed prior to WE of the primary tumor, and whenever possible in the same surgical setting, to maximize lymphatic drainage mapping techniques.18 Medical oncology referral, if needed, is usually made after WE.

SLNB remains the standard for lymph node staging. It is controversial mainly in its use for very thin or very thick lesions. Randomized controlled trials, including the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial,24 have shown no difference in melanoma-specific survival for patients with intermediate-thickness melanomas who had undergone SLNB.24

Many professional organizations consider SLNB to be the most significant prognostic indicator of disease recurrence. With a negative SLNB result, the risk of regional node recurrence is 5% or lower.18,25 In addition, sentinel lymph node status is a critical determinant for systemic adjuvant therapy consideration and clinical trial eligibility. For patients who have primary cutaneous melanoma without clinical lymphadenopathy, an online tool is available for patients to use with their physician in predicting the likelihood of SLNB positivity.26

Recommendations for SLNB, supported by multidisciplinary consensus:18

- Do not pursue SLNB for melanoma in situ or most cutaneous melanomas < 0.8 mm without ulceration (T1a). (See TABLE 127)

- Discuss SLNB with patients who have T1a melanoma and additional adverse features: young age, high mitotic rate, lymphovascular invasion, and nevus depth close to 0.8 mm with positive deep biopsy margins.

- Discuss SLNB with patients who have T1b disease (< 0.8 mm with ulceration, or 0.8-1 mm), although rates of SLNB positivity are low.

- Offer SLNB to patients with T2a and higher disease (> 1 mm).18

Continue to: Patients who have...

Patients who have clinical Stage I or II disease (TABLE 127)

Melanoma in women: Considerations to keep in mind

Hormonal influences of pregnancy, lactation, contraception, and menopause introduce special considerations regarding melanoma, which is the most common cancer occurring during pregnancy, accounting for 31% of new malignancies.33 Risk of melanoma lessens, however, for women who first give birth at a younger age or who have had > 5 live births.18,34,35 There is no evidence that nevi darken during pregnancy, although nevi on the breast and abdomen may seem to enlarge due to skin stretching.18 All changing nevi in pregnancy warrant an examination, preferably with dermoscopy, and patients should be offered biopsy if there are any nevus characteristics associated with melanoma.18

The effect of pregnancy on an existing melanoma is not fully understood, but evidence from controlled studies shows no negative effect. Recent working group guidelines advise WE with local anesthesia without delay in pregnant patients.18 Definitive treatment after melanoma diagnosis should take a multidisciplinary approach involving obstetric care coordinated with Dermatology, Surgery, and Medical Oncology.18

Most recommendations on the timing of pregnancy following a melanoma diagnosis have limited evidence. One meta-analysis concluded that pregnancy occurring after successful treatment of melanoma did not change a woman’s prognosis.36 Current guidelines do not recommend delaying future pregnancy if a woman had an early-stage melanoma. For melanomas deemed higher risk, a woman could consider a 2- to 3-year delay in the next planned pregnancy, owing to current data on recurrence rates.18

A systematic review of women who used hormonal contraception or postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy (HRT) showed no associated increased risk of melanoma.35 An additional randomized trial showed no effect of HRT on melanoma risk.37

Continue to: Systemic melanoma treatment and common adverse effects

Systemic melanoma treatment and common adverse effects

Multiple systemic therapies have been approved for the treatment of advanced or unresectable cutaneous melanomas. While these treatments are managed primarily by Oncology in concert with Dermatology, an awareness of the medications’ common dermatologic toxicities is important for the primary care provider. The 2 broad categories of FDA-approved systemic medications for advanced melanoma are mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors, each having its own set of adverse cutaneous effects.

MAPK pathway–targeting drugs include the B-Raf proto-oncogene serine/threonine-kinase inhibitors (BRAFIs) vemurafenib and dabrafenib, and the MAPK inhibitors (MEKIs) trametinib and cobimetinib. The most common adverse skin effects in MAPK pathway–targeting drugs are severe ultraviolet photosensitivity, cutaneous epidermal neoplasms (particularly squamous cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma-type), thick actinic keratosis, wart-like keratosis, painful palmoplantar keratosis, and dry skin.38 These effects are most commonly seen with BRAFI monotherapy and can be abated with the addition of a MEKI. MEKI therapy can cause acneiform eruptions and paronychia.39 Additional adverse effects include diarrhea, pyrexia, arthralgias, and fatigue for BRAFIs and diarrhea, fatigue, and peripheral edema for MEKIs.40

Immune checkpoint inhibitors include anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), anti-PD-1 (pembrolizumab and nivolumab), and anti-PDL-1 (atezolizumab). Adverse skin effects include morbilliform rash with or without an associated itch, itch with or without an associated rash, vitiligo, and lichenoid skin rashes. PD-1 and PDL-1 inhibitors have been associated with flares or unmasking of atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, sarcoidosis, and autoimmune bullous disease.18 Diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, elevated liver enzymes, hypophysitis, and thyroiditis are some of the more common noncutaneous adverse effects reported with CTLA-4 inhibitors, while fatigue, diarrhea, nausea, pneumonitis, and thyroid disease are seen with anti-PD-1/PDL-1 therapy.3

A look at the prognosis

For patients diagnosed with primary cutaneous melanoma between 2011 and 2017, the 5-year survival rate for localized disease (Stages I-II) was 99%.1 For regional (Stage III) and distant (Stage IV) disease, the 5-year survival rates were 68% and 30%, respectively.1 With the advent of adjuvant systemic therapy, 5-year overall survival rates for metastatic melanoma have markedly improved from < 10% to up to 40% to 50%.41 The 3-year survival rate for patients with high tumor burden, brain metastasis, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase remains at < 10%.42 Relative survival decreases with increased age, although survival is higher in women than in men.43 Risk of melanoma recurrence after surgical excision is high in patients with stage IIB, IIC, III and IV (resectable) disease. The most important risk factor for recurrence is primary tumor thickness.44 The most common site of first recurrence in stage I-II disease is regional lymph node metastasis (42.8%), closely followed by distant metastasis (37.6%).44

Long-term follow-up and surveillance

Recommendations for long-term care of patients with melanoma have evolved with advances in treatment, prognostication, and imaging. Caring for these patients requires a multidisciplinary approach wherein the family physician provides frontline care and team coordination. Since most recurrences are discovered by the patient or the patient’s family, patient education and self-examination are the cost-effective foundation for recurrence screening. In a trial of patients and partners, a 30-minute structured session on skin examination followed by physician reminders every 4 months increased the detection of melanoma recurrence without significant increases in patient visits.45

Continue to: Patient education should include sun safety...

Patient education should include sun safety (wearing sun-protective clothing, using broad-spectrum sunscreen, and avoiding sun exposure during peak times of the day). The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) says the level of evidence is insufficient to support routine skin cancer screening in adults.46 However, the USPSTF recommends discussing efforts to minimize UV radiation exposure to prevent skin cancer in fair-skinned individuals 10 to 24 years of age.

Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines have outlined the follow-up frequency for all melanoma patients. TABLE 232 outlines those recommendations in addition to self-examination and patient education.

Melanoma epidemic or overdiagnosis?

Over the past 2 decades, a marked rise in the incidence of melanoma has been reported in developed countries worldwide, although melanoma mortality rates have not increased as rapidly, with melanoma-specific survival stable in most groups.47-50 Due to conflicting evidence, significant disagreement exists as to whether this is an actual epidemic caused by a true rise in disease burden or is merely an artifact stemming from overdiagnosis.47

Evidence supporting a true melanoma epidemic includes population-based studies demonstrating greater UV radiation–induced carcinogenesis (from the sun and tanning bed use), a larger aging population, and increased incidence regardless of socioeconomic status.47 Those challenging the validity of an epidemic instead attribute the rising incidence to early-detection public awareness campaigns, expanded screenings, improved diagnostic modalities, and increased biopsies. They also credit lower pathologic thresholds that help identify thinner tumors with little to no metastatic potential.48 Additionally, multiple studies report an increased incidence in melanomas of all histologic subtypes and thicknesses, not just thinner, more curable tumors.49,51,52 Although increased screening and biopsies are effective, they alone cannot account for the sharp rise in melanoma cases.47 This “melanoma paradox” of increasing incidence without a parallel increase in mortality remains unsettled.47

CASE

Your patient had Stage IIA disease and a WE was performed with 1-cm margins. Ultrasound of the axilla identified an enlarged node, which was removed and found not to be diseased. He has now returned to have you look at another lesion identified by his spouse. His review of symptoms is negative. His initial melanoma was removed 2 years earlier, and his last dermatology skin exam was 5 months prior. You look at the lesion using a dermatoscope and do not note any worrisome features. You recommend that the patient photograph the area for reexamination and follow-up with his dermatologist next month for a 6-month follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jessica Servey, MD, 4301 Jones Bridge Road, Bethesda, MD 20814; [email protected]

1. NIH. Cancer stat facts: melanoma of the skin. 2018. Accessed May 13, 2021. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html

2. Watts CG, Dieng M, Morton RL, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for identification, screening and follow-up of individuals at high risk of primary cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:33-47.

3. Schadendorf D, van Akkooi ACJ, Berking C, et al. Melanoma. Lancet. 2018;392:971-984.

4. Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Chuchu N, et al. Dermoscopy, with and without visual inspection, for diagnosing melanoma in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018(12):CD011902.

5. Morris JB, Alfonso SV, Hernandez N, et al. Examining the factors associated with past and present dermoscopy use among family physicians. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:63-70.

6. Henning JS, Dusza SW, Wang SQ, et al. The CASH (color, architecture, symmetry, and homogeneity) algorithm for dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:45-52.

7. Rosendahl C, Cameron A, McColl I, et al. Dermatoscopy in routine practice — “chaos and clues”. Aust Fam Physician. 2012;41:482-487.

8. Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Zalaudek I, et al. Three-point checklist of dermoscopy: a new screening method for early detection of melanoma. Dermatology. 2004;208:27-31.

9. Argenziano G, Fabbrocini G, Carli P, et al. Epiluminescence microscopy for the diagnosis of doubtful melanocytic skin lesions. Comparison of the ABCD rule of dermatoscopy and a new 7-point checklist based on pattern analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1563-1570.

10. Marghoob AA, Usatine RP, Jaimes N. Dermoscopy for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:441-450.

11. Rogers T, Marino ML, Dusza SW, et al. A clinical aid for detecting skin cancer: the Triage Amalgamated Dermoscopic Algorithm (TADA). J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29:694-701.

12. Argenziano G, Soyer HP, Chimenti S, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions: results of a consensus meeting via the Internet. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:679-93.

13. Carli P, Quercioli E, Sestini S, et al. Pattern analysis, not simplified algorithms, is the most reliable method for teaching dermoscopy for melanoma diagnosis to residents in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:981-984.

14. Yélamos O, Braun RP, Liopyris K, et al. Usefulness of dermoscopy to improve the clinical and histopathologic diagnosis of skin cancers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:365-377.

15. Westerhoff K, McCarthy WH, Menzies SW. Increase in the sensitivity for melanoma diagnosis by primary care physicians using skin surface microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1016-1020.

16. Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

17. Usatine RP, Shama LK, Marghoob AA, et al. Dermoscopy in family medicine: a primer. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:E1-E11.

18. Swetter SM, Tsao H, Bichakjian CK, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of primary cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:208-250.

19. Seiverling EV, Ahrns HT, Bacik LC, et al. Biopsies for skin cancer detection: dispelling the myths. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:270-274.

20. Martin RCG, Scoggins CR, Ross MI, et al. Is incisional biopsy of melanoma harmful? Am J Surg. 2005;190:913-917.

21. Mir M, Chan CS, Khan F, et al. The rate of melanoma transection with various biopsy techniques and the influence of tumor transection on patient survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:452-458.

22. Breslow A. Thickness, cross-sectional areas and depth of invasion in the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg. 1970;172:902-908

23. Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th ed cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:472-492.

24. Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:599-609.

25. Valsecchi ME, Silbermins D, de Rosa N, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with melanoma: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1479-1487.

26. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Risk of sentinel lymph node metastasis nomogram. Accessed May 13, 2021. www.mskcc.org/nomograms/melanoma/sentinel_lymph_node_metastasis

27. Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer International Publishing; 2017:563-581.

28. Xing Y, Bronstein Y, Ross MI, et al. Contemporary diagnostic imaging modalities for the staging and surveillance of melanoma patients: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:129-142.

29. Tsao H, Feldman M, Fullerton JE, et al. Early detection of asymptomatic pulmonary melanoma metastases by routine chest radiographs is not associated with improved survival. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:67-70.

30. Wang TS, Johnson TM, Cascade PN, et al. Evaluation of staging chest radiographs and serum lactate dehydrogenase for localized melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:399-405.

31. Yancovitz M, Finelt N, Warycha MA, et al. Role of radiologic imaging at the time of initial diagnosis of stage T1b-T3b melanoma. Cancer. 2007; 110:1107-1114.

32. Swetter SM, Thompson JA, Albertini MR, et al. NCCN Guidelines: cutaneous melanoma, version 4.2020. Accessed June 7, 2021. http://medi-guide.meditool.cn/ymtpdf/ACC90A18-6CDF-9443-BF3F-E29394D495E8.pdf

33. Stensheim H, Møller B, van Dijk T, et al. Cause-specific survival for women diagnosed with cancer during pregnancy or lactation: a registry-based cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:45-51.

34. Lens MB, Rosdahl I, Ahlbom A, et al. Effect of pregnancy on survival in women with cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4369-4375.

35. Gandini S, Iodice S, Koomen E, et al. Hormonal and reproductive factors in relation to melanoma in women: current review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2607-2617.

36. Byrom L, Olsen CM, Knight L, et al. Does pregnancy after a diagnosis of melanoma affect prognosis? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:875-882.

37. Tang JY, Spaunhurst KM, Chlebowski RT, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and risks of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers: women’s health initiative randomized trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1469-1475.

38. Carlos G, Anforth R, Clements A, et al. Cutaneous toxic effects of BRAF inhibitors alone and in combination with MEK inhibitors for metastatic melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1103-1109.

39. Macdonald JB, Macdonald B, Golitz LE, et al. Cutaneous adverse effects of targeted therapies: part I: inhibitors of the cellular membrane. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:203-218.

40. Welsh SJ, Corrie PG. Management of BRAF and MEK inhibitor toxicities in patients with metastatic melanoma. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2015;7:122-136.

41. Kandolf Sekulovic L, Peris K, Hauschild A, et al. More than 5000 patients with metastatic melanoma in Europe per year do not have access to recommended first-line innovative treatments. Eur J Cancer. 2017;75:313-322.

42. Long GV, Grob JJ, Nathan P, et al. Factors predictive of response, disease progression, and overall survival after dabrafenib and trametinib combination treatment: a pooled analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1743-1754.

43. Trends in incidence and survival in patients with melanoma, 1974-2013. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:1396-1414.

44. Lyth J, Falk M, Maroti M, et al. Prognostic risk factors of first recurrence in patients with primary stages I–II cutaneous malignant melanoma – from the population‐based Swedish melanoma register. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1468-1474.

45. Robinson JK, Wayne JD, Martini MC, et al. Early detection of new melanomas by patients with melanoma and their partners using a structured skin self-examination skills training intervention: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:979-985.

Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

47. Gardner LJ, Strunck JL, Wu YP, et al. Current controversies in early-stage melanoma: questions on incidence, screening, and histologic regression. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1-12.

48. Wei EX, Qureshi AA, Han J, et al. Trends in the diagnosis and clinical features of melanoma in situ (MIS) in US men and women: a prospective, observational study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:698-705.

49. Linos E, Swetter SM, Cockburn MG, et al. Increasing burden of melanoma in the United States. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:1666-1674.

50. Curchin DJ, Forward E, Dickison P, et al. The acceleration of melanoma in situ: a population-based study of melanoma incidence trends from Victoria, Australia, 1985-2015. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1791-1793.

51. Dennis LK. Analysis of the melanoma epidemic, both apparent and real: data from the 1973 through 1994 surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program registry. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:275-280.

52. Jemal A, Saraiya M, Patel P, et al. Recent trends in cutaneous melanoma incidence and death rates in the United States, 1992-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:S17-S25.

1. NIH. Cancer stat facts: melanoma of the skin. 2018. Accessed May 13, 2021. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html

2. Watts CG, Dieng M, Morton RL, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for identification, screening and follow-up of individuals at high risk of primary cutaneous melanoma: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:33-47.

3. Schadendorf D, van Akkooi ACJ, Berking C, et al. Melanoma. Lancet. 2018;392:971-984.

4. Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Chuchu N, et al. Dermoscopy, with and without visual inspection, for diagnosing melanoma in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018(12):CD011902.

5. Morris JB, Alfonso SV, Hernandez N, et al. Examining the factors associated with past and present dermoscopy use among family physicians. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:63-70.

6. Henning JS, Dusza SW, Wang SQ, et al. The CASH (color, architecture, symmetry, and homogeneity) algorithm for dermoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:45-52.

7. Rosendahl C, Cameron A, McColl I, et al. Dermatoscopy in routine practice — “chaos and clues”. Aust Fam Physician. 2012;41:482-487.

8. Soyer HP, Argenziano G, Zalaudek I, et al. Three-point checklist of dermoscopy: a new screening method for early detection of melanoma. Dermatology. 2004;208:27-31.

9. Argenziano G, Fabbrocini G, Carli P, et al. Epiluminescence microscopy for the diagnosis of doubtful melanocytic skin lesions. Comparison of the ABCD rule of dermatoscopy and a new 7-point checklist based on pattern analysis. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1563-1570.