User login

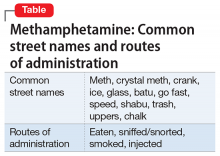

Use of methamphetamine, an N-methyl analog of amphetamine, is a serious public health problem; throughout the world an estimated 35.7 million people use the drug recreationally.1 Methamphetamine is easy to obtain because it is cheap to produce and can be synthesized anywhere. In the United States, methamphetamine is commonly manufactured in small-scale laboratories using relatively inexpensive, legally available ingredients. Large-scale manufacturing in clandestine laboratories also contributes to methamphetamine abuse. The drug, known as meth, crystal meth, ice, and other names, is available as a powder, tablet, or crystalline salt, and is used by various routes of administration (Table).

Although FDA-approved for treating attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, methamphetamine is taken recreationally for its euphoric effects; however, it also produces anhedonia, paranoia, and a host of cognitive deficits and other adverse effects.

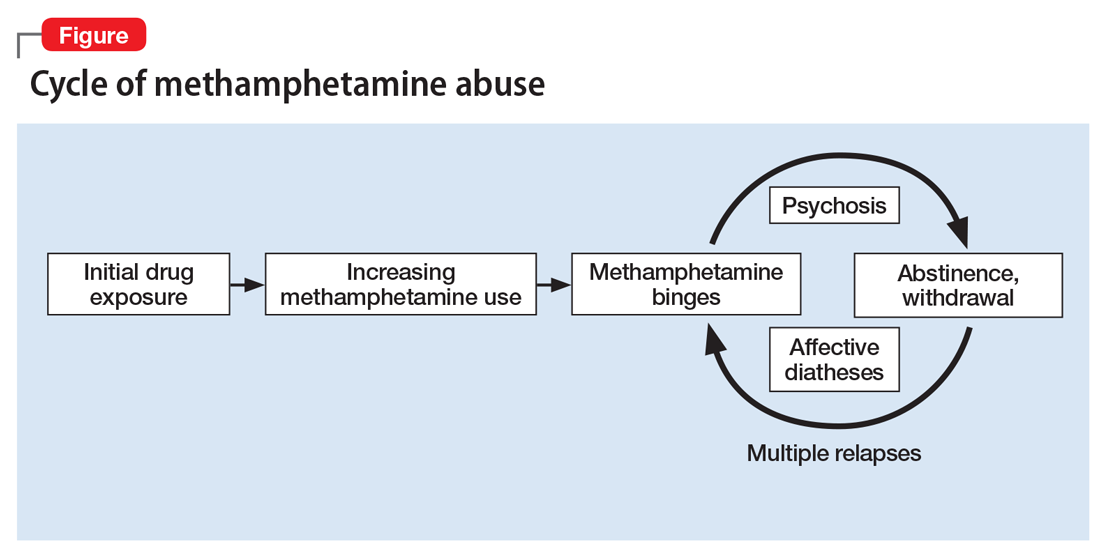

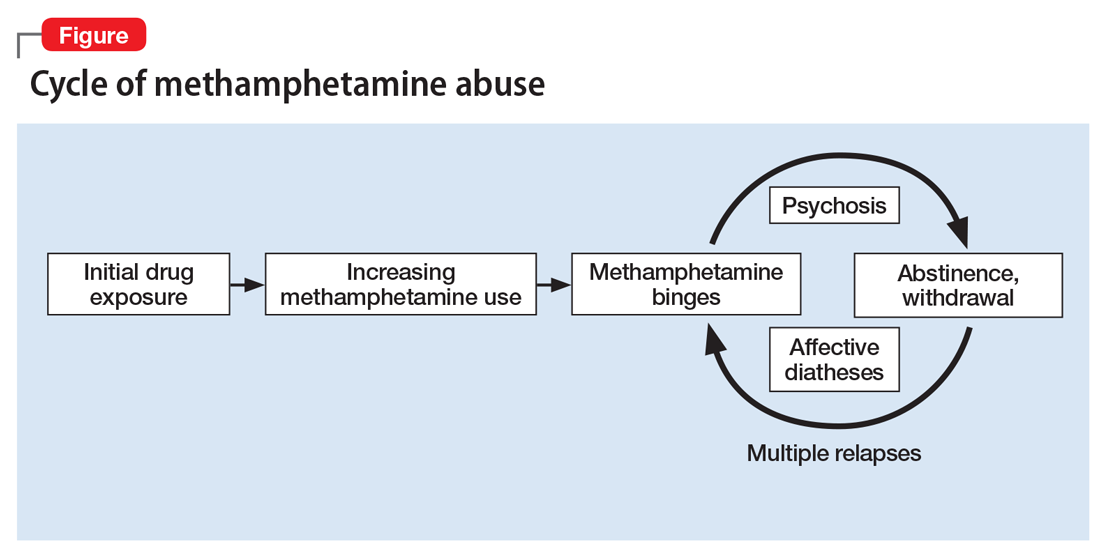

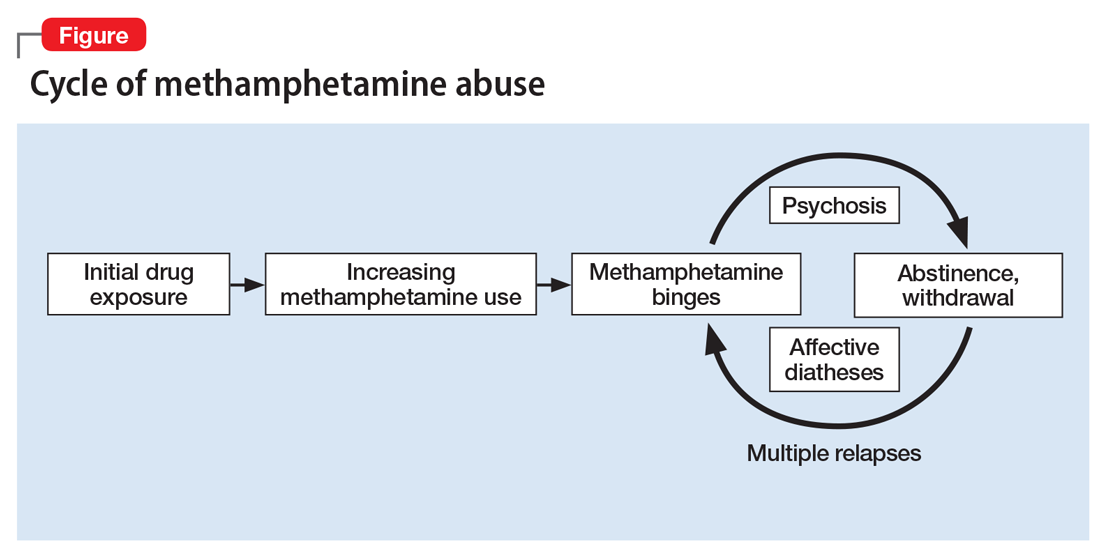

Methamphetamine causes psychiatric diseases that resemble naturally occurring illnesses but are more difficult to treat. Dependence occurs over a period of escalating use (Figure). Long-term exposure to the drug has been shown to cause severe neurotoxic and neuropathological effects with consequent disturbances in several cognitive domains.4

Despite advances in understanding the basic neurobiology of methamphetamine-induced effects on the brain, much remains to be done to translate this knowledge to treating patients and the complications that result from chronic abuse of this stimulant. In this review, we:

- provide a brief synopsis of the clinical presentation of patients who use methamphetamine

- describe some of the complications of methamphetamine abuse/dependence, focusing on methamphetamine-induced psychosis

- suggest ways to approach the treatment of these patients, including those with methamphetamine-induced psychosis.

Acute effects of methamphetamine use

Psychiatric symptoms. Patients under the influence of methamphetamine may present with clinical symptoms that mimic psychiatric disorders. For example, the drug can cause marked euphoria, hyperactivity, and disturbed speech patterns, thus mimicking a manic state. Patients also may present with anxiety, agitation, and irritability or aggressiveness. Although an individual may take methamphetamine for sexual enhancement, the drug can cause hypersexuality, which often is associated with unintended and unsafe sexual activities. These signs and symptoms are exacerbated during drug binges that can last for days, during which time large quantities of the drug are consumed.

Methamphetamine users may become preoccupied with their own thought patterns, and their actions can become compulsive and nonsensical. For example, a patient may become obsessed with an object of no specific value in his (her) environment, such as a doorknob or a cloud. Patients also may become suspicious of their friends and family members or think that police officers are after them. Less commonly, a patient also may suffer from poverty of speech, psychomotor retardation, and diminished social engagement similar to that reported in some patients with schizophrenia with deficit syndrome. Usually, acute symptoms will last 4 to 7 days after drug cessation, and then resolve completely with protracted abstinence from the drug.

Neurologic signs of methamphetamine use include hemorrhagic strokes in young people without any evidence of previous neurologic impairments. Studies have documented similarities between methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity and traumatic brain injury.5 Postmortem studies have reported the presence of arteriovenous malformation in some patients with hemorrhagic strokes.

Hyperthermia is a dangerous acute effect of methamphetamine use. High body temperatures can cause both peripheral and central abnormalities, including muscular and cardiovascular dysfunction, renal failure secondary to rhabdomyolysis, heat stroke, and other heat-induced malignant syndromes. Some of the central dysfunctions may be related to heat-induced production of free radicals in various brain regions. There are no pharmacologic treatments for methamphetamine-induced thermal dysregulation.6 Therefore, clinicians need to focus on reducing body temperature by using cooling fans or cold water baths. Efforts should be made to avoid overhydrating patients because of the risk of developing the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion.

Chronic methamphetamine abuse

Psychosis is a long-term complication of chronic abuse of the drug.7 Although psychosis has been a reported complication of methamphetamine use since the 1950s,8 most of the subsequent literature is from Japan, where methamphetamine use was highly prevalent after World War II.9,10 The prevalence of methamphetamine-induced psychosis in methamphetamine-dependent patients varies from 13% (in the United States11) to 50% (in Asia12). This difference might be related to variability in the purity of methamphetamine used in different locations.

Methamphetamine users may experience a pre-psychotic state that consists of ideas of reference and delusional moods. This is followed by a psychotic state that includes hallucinations and delusions. The time it takes to develop these symptoms can vary from a few months up to >20 years after starting to use methamphetamine.10,13 Psychosis can occur in patients who do not have a history of psychiatric illness.10

The clinical presentation of methamphetamine-induced psychosis includes delusions of reference and persecutions.8-10 Paranoid delusions may be accompanied by violent behavior. Some patients may present with grandiose or jealousy delusions. Patients may experience auditory, tactile, or visual hallucinations. They may exhibit mania and logorrheic verbal outputs, symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of methamphetamine-induced mood disorder with manic features. Patients who use large daily doses of the drug also may report that there are ants or other parasites crawling under their skin (eg, formication, “meth mites”) and might present with infected excoriations of their skin as a result of attempting to remove insects. This is clinically important because penicillin-resistant bacteria are common in patients who use methamphetamine, and strains tend to be virulent.

Psychotic symptoms can last from a few days to several weeks after stopping methamphetamine use, although methamphetamine-induced psychosis can persist after long periods of abstinence.14 Psychotic symptoms may recur with re-exposure to the drug9 or repeated stressful life events.15 Patients with recurrent psychosis in the absence of a drug trigger appear to have high levels of peripheral norepinephrine.15 Patients with psychosis caused by long-term methamphetamine use will not necessarily show signs of sympathomimetic dysfunction because they may not have any methamphetamine in the body when they first present for clinical evaluation. Importantly, patients with methamphetamine-induced psychosis have been reported to have poor outcomes at follow-up.16 They have an increased risk of suicide, recurrent drug-induced psychosis, and comorbid alcohol abuse.16

Doses required to induce psychosis vary from patient to patient and may depend on the patient’s genetic background and/or environmental conditions. Methamphetamine can increase the severity of many psychiatric symptoms17 and may expedite the development of schizophrenia in first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia.18

The diagnosis of methamphetamine-induced psychosis should focus on differentiating it from schizophrenia. Wang et al19 found similar patterns of delusions in patients with schizophrenia and those with methamphetamine-induced psychosis. However, compared with patients with schizophrenia, patients with methamphetamine-induced psychosis have a higher prevalence of visual and tactile hallucinations, and less disorganization, blunted affect, and motor retardation. Some patients may present with depression and suicidal ideation; these features may be more prominent during withdrawal, but also may be obvious during periods of active use.16

Although these clinical features may be helpful initially, more comparative neurobiologic investigations are needed to identify potential biologic differences between schizophrenia and methamphetamine-induced psychosis because these differences will impact therapeutic approaches to these diverse population groups.

Neurologic complications. Chronic methamphetamine users may develop various neurologic disorders.20 They may present with stereotypies involving finger movements or repeated rubbing of mouth or face, orofacial dyskinesia, and choreoathetoid movements reminiscent of classical neurologic disorders. These movement disorders can persist after cessation of methamphetamine use. In some cases, these movement abnormalities may respond to dopamine receptor antagonists such as haloperidol.

Neuropsychological findings. Chronic methamphetamine users show mild signs of cognitive decline that affects a broad range of neuropsychological functions.21-23 There are deficits in several cognitive processes that are dependent on the function of frontostriatal and limbic circuits.24-26 Specifically, episodic memory, executive functions, complex information processing speed, and psychomotor functions all have been reported to be negatively impacted.

Methamphetamine use often results in psychiatric distress that impacts users’ interpersonal relationships.27 Additionally, impulsivity may exacerbate their psychosocial difficulties and promote maintenance of drug-seeking behaviors.28 Cognitive deficits lead to poor health outcomes, high-risk behaviors, employment difficulties, and repeated relapse.29,30

Partial recovery of neuropsychological functioning and improvement in affective distress can be achieved after sustained abstinence from methamphetamine, but recovery may not be complete. Because cognitive dysfunction can influence treatment outcomes, clinicians need to be fully aware of the cognitive status of those patients, and a thorough neuropsychological evaluation is necessary before initiating treatment.

Treatment

Methamphetamine abuse. Because patients who abuse methamphetamine are at high risk of developing psychosis, neurologic complications, and neuropsychological disorders, initiating treatment early in the course of their addiction is of paramount importance. Treatment of methamphetamine addiction is complicated by the fact that these patients have a high prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders, which clinicians need to keep in mind when selecting therapeutic interventions.

There are no FDA-approved agents for treating methamphetamine abuse.31 Several drugs have been tried with varying degrees of success, including bupropion, modafinil, and naltrexone. A study of modafinil found no clinically significant effects for treating methamphetamine abuse; however, only approximately one-half of participants in this study took modafinil as instructed.32 Certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, including fluoxetine and paroxetine, have not been shown to be effective in treating these patients. Naltrexone may be a reasonable medication to consider because of the high prevalence of comorbid alcohol abuse among methamphetamine users.

Other treatments for methamphetamine addiction consist of behavioral interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy. Clinical experience has shown that the risk of relapse depends on how long the patient has been abstinent prior to entering a treatment program, the presence of attention and memory deficits, and findings of poor decision-making on neuropsychological tests.

The presence of cognitive abnormalities has been reported to impact methamphetamine abusers’ response to treatment.33 These findings suggest the need to develop approaches that might improve cognition in patients who are undergoing treatment for methamphetamine abuse. The monoaminergic agent modafinil and similar drugs need to be evaluated in large populations to increase the possibility of identifying characteristics of patients who might respond to cognitive enhancement.34

Methamphetamine-induced psychosis. First-generation antipsychotics, such as haloperidol or fluphenazine, need to be used sparingly in patients with methamphetamine-induced psychosis because of the risk of developing extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and because these patients are prone to develop motor complications as a result of methamphetamine abuse. Second-generation antipsychotics, such as risperidone and olanzapine, may be more appropriate because of the lower risks of EPS.35 The presence of high norepinephrine levels in some patients with recurrent methamphetamine psychosis suggests that drugs that block norepinephrine receptors, such as prazosin or propranolol, might be of therapeutic benefit if they are shown to be effective in controlled clinical trials.

1. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2016. United Nations publication, Sales No. E.16.XI.7. http://www.unodc.org/wdr2016. Published 2016. Accessed September 28, 2017.

2. Krasnova IN, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine toxicity and messengers of death. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60(2):379-407.

3. Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(8):760-773.

4. Cadet JL, Bisagno V, Milroy CM. Neuropathology of substance use disorders. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(1):91-107.

5. Gold MS, Kobeissy FH, Wang KK, et al. Methamphetamine- and trauma-induced brain injuries: comparative cellular and molecular neurobiological substrates. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(2):118-127.

6. Gold MS, Graham NA, Kobeissy FH, et al. Speed, cocaine, and other psychostimulants death rates. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(7):1184.

7. Shelly J, Uhlmann A, Sinclair H, et al. First-rank symptoms in methamphetamine psychosis and schizophrenia. Psychopathology. 2016;49(6):429-435.

8. Connell PH. Amphetamine psychosis. In: Connell PH. Maudsley monographs. No. 5. London, United Kingdom: Oxford Press; 1958:5.

9. Sato M. A lasting vulnerability to psychosis in patients with previous methamphetamine psychosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;654(1):160-170.

10. Ujike H, Sato M. Clinical features of sensitization to methamphetamine observed in patients with methamphetamine dependence and psychosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1025(1):279-287.

11. Glasner-Edwards S, Mooney LJ, Marinelli-Casey P, et al; Methamphetamine Treatment Project Corporate Authors. Psychopathology in methamphetamine-dependent adults 3 years after treatment. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(1):12-20.

12. Sulaiman AH, Said MA, Habil MH, et al. The risk and associated factors of methamphetamine psychosis in methamphetamine-dependent patients in Malaysia. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(suppl 1):S89-S94.

13. Fasihpour B, Molavi S, Shariat SV. Clinical features of inpatients with methamphetamine-induced psychosis. J Ment Health. 2013;22(4):341-349.

14. Akiyama K, Saito A, Shimoda K. Chronic methamphetamine psychosis after long-term abstinence in Japanese incarcerated patients. Am J Addict. 2011;20(3):240-249.

15. Yui K, Goto K, Ikemoto S, et al. Methamphetamine psychosis: spontaneous recurrence of paranoid-hallucinatory states and monoamine neurotransmitter function. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17(1):34-43.

16. Kittirattanapaiboon P, Mahatnirunkul S, Booncharoen H, et al. Long-term outcomes in methamphetamine psychosis patients after first hospitalisation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(4):456-461.

17. McKetin R, Dawe S, Burns RA, et al. The profile of psychiatric symptoms exacerbated by methamphetamine use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161:104-109.

18. Li H, Lu Q, Xiao E, et al. Methamphetamine enhances the development of schizophrenia in first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(2):107-113.

19. Wang LJ, Lin SK, Chen YC, et al. Differences in clinical features of methamphetamine users with persistent psychosis and patients with schizophrenia. Psychopathology. 2016;49(2):108-115.

20. Rusyniak DE. Neurologic manifestations of chronic methamphetamine abuse. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36(2):261-275.

21. Simon SL, Domier C, Carnell J, et al. Cognitive impairment in individuals currently using methamphetamine. Am J Addict. 2000;9(3):222-231.

22. Paulus MP, Hozack NE, Zauscher BE, et al. Behavioral and functional neuroimaging evidence for prefrontal dysfunction in methamphetamine-dependent subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26(1):53-63.

23. Rendell PG, Mazur M, Henry JD. Prospective memory impairment in former users of methamphetamine. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009;203(3):609-616.

24. Monterosso JR, Ainslie G, Xu J, et al. Frontoparietal cortical activity of methamphetamine-dependent and comparison subjects performing a delay discounting task. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007;28(5):383-393.

25. Nestor LJ, Ghahremani DG, Monterosso J, et al. Prefrontal hypoactivation during cognitive control in early abstinent methamphetamine-dependent subjects. Psychiatry Res. 2011;194(3):287-295.

26. Scott JC, Woods SP, Matt GE, et al. Neurocognitive effects of methamphetamine: a critical review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev. 2007;17(3):275-297.

27. Cretzmeyer M, Sarrazin MV, Huber DL, et al. Treatment of methamphetamine abuse: research findings and clinical directions. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24(3):267-277.

28. Semple SJ, Zians J, Grant I, et al. Impulsivity and methamphetamine use. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;29(2):85-93.

29. Hester R, Lee N, Pennay A, et al. The effects of modafinil treatment on neuropsychological and attentional bias performance during 7-day inpatient withdrawal from methamphetamine dependence. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;18(6):489-497.

30. Weber E, Blackstone K, Iudicello JE, et al; Translational Methamphetamine AIDS Research Center (TMARC) Group. Neurocognitive deficits are associated with unemployment in chronic methamphetamine users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125(1-2):146-153.

31. Ballester J, Valentine G, Sofuoglu M. Pharmacological treatments for methamphetamine addiction: current status and future directions. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2017;10(3):305-314.

32. Anderson AL, Li SH, Biswas K, et al. Modafinil for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120(1-3):135-141.

33. Cadet JL, Bisagno V. Neuropsychological consequences of chronic drug use: relevance to treatment approaches. Front Psychiatry. 2016;6:189.

34. Loland CJ, Mereu M, Okunola OM, et al. R-modafinil (armodafinil): a unique dopamine uptake inhibitor and potential medication for psychostimulant abuse. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(5):405-413.

35. Farnia V, Shakeri J, Tatari F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of aripiprazole versus risperidone for the treatment of amphetamine-induced psychosis. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40(1):10-15.

Use of methamphetamine, an N-methyl analog of amphetamine, is a serious public health problem; throughout the world an estimated 35.7 million people use the drug recreationally.1 Methamphetamine is easy to obtain because it is cheap to produce and can be synthesized anywhere. In the United States, methamphetamine is commonly manufactured in small-scale laboratories using relatively inexpensive, legally available ingredients. Large-scale manufacturing in clandestine laboratories also contributes to methamphetamine abuse. The drug, known as meth, crystal meth, ice, and other names, is available as a powder, tablet, or crystalline salt, and is used by various routes of administration (Table).

Although FDA-approved for treating attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, methamphetamine is taken recreationally for its euphoric effects; however, it also produces anhedonia, paranoia, and a host of cognitive deficits and other adverse effects.

Methamphetamine causes psychiatric diseases that resemble naturally occurring illnesses but are more difficult to treat. Dependence occurs over a period of escalating use (Figure). Long-term exposure to the drug has been shown to cause severe neurotoxic and neuropathological effects with consequent disturbances in several cognitive domains.4

Despite advances in understanding the basic neurobiology of methamphetamine-induced effects on the brain, much remains to be done to translate this knowledge to treating patients and the complications that result from chronic abuse of this stimulant. In this review, we:

- provide a brief synopsis of the clinical presentation of patients who use methamphetamine

- describe some of the complications of methamphetamine abuse/dependence, focusing on methamphetamine-induced psychosis

- suggest ways to approach the treatment of these patients, including those with methamphetamine-induced psychosis.

Acute effects of methamphetamine use

Psychiatric symptoms. Patients under the influence of methamphetamine may present with clinical symptoms that mimic psychiatric disorders. For example, the drug can cause marked euphoria, hyperactivity, and disturbed speech patterns, thus mimicking a manic state. Patients also may present with anxiety, agitation, and irritability or aggressiveness. Although an individual may take methamphetamine for sexual enhancement, the drug can cause hypersexuality, which often is associated with unintended and unsafe sexual activities. These signs and symptoms are exacerbated during drug binges that can last for days, during which time large quantities of the drug are consumed.

Methamphetamine users may become preoccupied with their own thought patterns, and their actions can become compulsive and nonsensical. For example, a patient may become obsessed with an object of no specific value in his (her) environment, such as a doorknob or a cloud. Patients also may become suspicious of their friends and family members or think that police officers are after them. Less commonly, a patient also may suffer from poverty of speech, psychomotor retardation, and diminished social engagement similar to that reported in some patients with schizophrenia with deficit syndrome. Usually, acute symptoms will last 4 to 7 days after drug cessation, and then resolve completely with protracted abstinence from the drug.

Neurologic signs of methamphetamine use include hemorrhagic strokes in young people without any evidence of previous neurologic impairments. Studies have documented similarities between methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity and traumatic brain injury.5 Postmortem studies have reported the presence of arteriovenous malformation in some patients with hemorrhagic strokes.

Hyperthermia is a dangerous acute effect of methamphetamine use. High body temperatures can cause both peripheral and central abnormalities, including muscular and cardiovascular dysfunction, renal failure secondary to rhabdomyolysis, heat stroke, and other heat-induced malignant syndromes. Some of the central dysfunctions may be related to heat-induced production of free radicals in various brain regions. There are no pharmacologic treatments for methamphetamine-induced thermal dysregulation.6 Therefore, clinicians need to focus on reducing body temperature by using cooling fans or cold water baths. Efforts should be made to avoid overhydrating patients because of the risk of developing the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion.

Chronic methamphetamine abuse

Psychosis is a long-term complication of chronic abuse of the drug.7 Although psychosis has been a reported complication of methamphetamine use since the 1950s,8 most of the subsequent literature is from Japan, where methamphetamine use was highly prevalent after World War II.9,10 The prevalence of methamphetamine-induced psychosis in methamphetamine-dependent patients varies from 13% (in the United States11) to 50% (in Asia12). This difference might be related to variability in the purity of methamphetamine used in different locations.

Methamphetamine users may experience a pre-psychotic state that consists of ideas of reference and delusional moods. This is followed by a psychotic state that includes hallucinations and delusions. The time it takes to develop these symptoms can vary from a few months up to >20 years after starting to use methamphetamine.10,13 Psychosis can occur in patients who do not have a history of psychiatric illness.10

The clinical presentation of methamphetamine-induced psychosis includes delusions of reference and persecutions.8-10 Paranoid delusions may be accompanied by violent behavior. Some patients may present with grandiose or jealousy delusions. Patients may experience auditory, tactile, or visual hallucinations. They may exhibit mania and logorrheic verbal outputs, symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of methamphetamine-induced mood disorder with manic features. Patients who use large daily doses of the drug also may report that there are ants or other parasites crawling under their skin (eg, formication, “meth mites”) and might present with infected excoriations of their skin as a result of attempting to remove insects. This is clinically important because penicillin-resistant bacteria are common in patients who use methamphetamine, and strains tend to be virulent.

Psychotic symptoms can last from a few days to several weeks after stopping methamphetamine use, although methamphetamine-induced psychosis can persist after long periods of abstinence.14 Psychotic symptoms may recur with re-exposure to the drug9 or repeated stressful life events.15 Patients with recurrent psychosis in the absence of a drug trigger appear to have high levels of peripheral norepinephrine.15 Patients with psychosis caused by long-term methamphetamine use will not necessarily show signs of sympathomimetic dysfunction because they may not have any methamphetamine in the body when they first present for clinical evaluation. Importantly, patients with methamphetamine-induced psychosis have been reported to have poor outcomes at follow-up.16 They have an increased risk of suicide, recurrent drug-induced psychosis, and comorbid alcohol abuse.16

Doses required to induce psychosis vary from patient to patient and may depend on the patient’s genetic background and/or environmental conditions. Methamphetamine can increase the severity of many psychiatric symptoms17 and may expedite the development of schizophrenia in first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia.18

The diagnosis of methamphetamine-induced psychosis should focus on differentiating it from schizophrenia. Wang et al19 found similar patterns of delusions in patients with schizophrenia and those with methamphetamine-induced psychosis. However, compared with patients with schizophrenia, patients with methamphetamine-induced psychosis have a higher prevalence of visual and tactile hallucinations, and less disorganization, blunted affect, and motor retardation. Some patients may present with depression and suicidal ideation; these features may be more prominent during withdrawal, but also may be obvious during periods of active use.16

Although these clinical features may be helpful initially, more comparative neurobiologic investigations are needed to identify potential biologic differences between schizophrenia and methamphetamine-induced psychosis because these differences will impact therapeutic approaches to these diverse population groups.

Neurologic complications. Chronic methamphetamine users may develop various neurologic disorders.20 They may present with stereotypies involving finger movements or repeated rubbing of mouth or face, orofacial dyskinesia, and choreoathetoid movements reminiscent of classical neurologic disorders. These movement disorders can persist after cessation of methamphetamine use. In some cases, these movement abnormalities may respond to dopamine receptor antagonists such as haloperidol.

Neuropsychological findings. Chronic methamphetamine users show mild signs of cognitive decline that affects a broad range of neuropsychological functions.21-23 There are deficits in several cognitive processes that are dependent on the function of frontostriatal and limbic circuits.24-26 Specifically, episodic memory, executive functions, complex information processing speed, and psychomotor functions all have been reported to be negatively impacted.

Methamphetamine use often results in psychiatric distress that impacts users’ interpersonal relationships.27 Additionally, impulsivity may exacerbate their psychosocial difficulties and promote maintenance of drug-seeking behaviors.28 Cognitive deficits lead to poor health outcomes, high-risk behaviors, employment difficulties, and repeated relapse.29,30

Partial recovery of neuropsychological functioning and improvement in affective distress can be achieved after sustained abstinence from methamphetamine, but recovery may not be complete. Because cognitive dysfunction can influence treatment outcomes, clinicians need to be fully aware of the cognitive status of those patients, and a thorough neuropsychological evaluation is necessary before initiating treatment.

Treatment

Methamphetamine abuse. Because patients who abuse methamphetamine are at high risk of developing psychosis, neurologic complications, and neuropsychological disorders, initiating treatment early in the course of their addiction is of paramount importance. Treatment of methamphetamine addiction is complicated by the fact that these patients have a high prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders, which clinicians need to keep in mind when selecting therapeutic interventions.

There are no FDA-approved agents for treating methamphetamine abuse.31 Several drugs have been tried with varying degrees of success, including bupropion, modafinil, and naltrexone. A study of modafinil found no clinically significant effects for treating methamphetamine abuse; however, only approximately one-half of participants in this study took modafinil as instructed.32 Certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, including fluoxetine and paroxetine, have not been shown to be effective in treating these patients. Naltrexone may be a reasonable medication to consider because of the high prevalence of comorbid alcohol abuse among methamphetamine users.

Other treatments for methamphetamine addiction consist of behavioral interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy. Clinical experience has shown that the risk of relapse depends on how long the patient has been abstinent prior to entering a treatment program, the presence of attention and memory deficits, and findings of poor decision-making on neuropsychological tests.

The presence of cognitive abnormalities has been reported to impact methamphetamine abusers’ response to treatment.33 These findings suggest the need to develop approaches that might improve cognition in patients who are undergoing treatment for methamphetamine abuse. The monoaminergic agent modafinil and similar drugs need to be evaluated in large populations to increase the possibility of identifying characteristics of patients who might respond to cognitive enhancement.34

Methamphetamine-induced psychosis. First-generation antipsychotics, such as haloperidol or fluphenazine, need to be used sparingly in patients with methamphetamine-induced psychosis because of the risk of developing extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and because these patients are prone to develop motor complications as a result of methamphetamine abuse. Second-generation antipsychotics, such as risperidone and olanzapine, may be more appropriate because of the lower risks of EPS.35 The presence of high norepinephrine levels in some patients with recurrent methamphetamine psychosis suggests that drugs that block norepinephrine receptors, such as prazosin or propranolol, might be of therapeutic benefit if they are shown to be effective in controlled clinical trials.

Use of methamphetamine, an N-methyl analog of amphetamine, is a serious public health problem; throughout the world an estimated 35.7 million people use the drug recreationally.1 Methamphetamine is easy to obtain because it is cheap to produce and can be synthesized anywhere. In the United States, methamphetamine is commonly manufactured in small-scale laboratories using relatively inexpensive, legally available ingredients. Large-scale manufacturing in clandestine laboratories also contributes to methamphetamine abuse. The drug, known as meth, crystal meth, ice, and other names, is available as a powder, tablet, or crystalline salt, and is used by various routes of administration (Table).

Although FDA-approved for treating attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, methamphetamine is taken recreationally for its euphoric effects; however, it also produces anhedonia, paranoia, and a host of cognitive deficits and other adverse effects.

Methamphetamine causes psychiatric diseases that resemble naturally occurring illnesses but are more difficult to treat. Dependence occurs over a period of escalating use (Figure). Long-term exposure to the drug has been shown to cause severe neurotoxic and neuropathological effects with consequent disturbances in several cognitive domains.4

Despite advances in understanding the basic neurobiology of methamphetamine-induced effects on the brain, much remains to be done to translate this knowledge to treating patients and the complications that result from chronic abuse of this stimulant. In this review, we:

- provide a brief synopsis of the clinical presentation of patients who use methamphetamine

- describe some of the complications of methamphetamine abuse/dependence, focusing on methamphetamine-induced psychosis

- suggest ways to approach the treatment of these patients, including those with methamphetamine-induced psychosis.

Acute effects of methamphetamine use

Psychiatric symptoms. Patients under the influence of methamphetamine may present with clinical symptoms that mimic psychiatric disorders. For example, the drug can cause marked euphoria, hyperactivity, and disturbed speech patterns, thus mimicking a manic state. Patients also may present with anxiety, agitation, and irritability or aggressiveness. Although an individual may take methamphetamine for sexual enhancement, the drug can cause hypersexuality, which often is associated with unintended and unsafe sexual activities. These signs and symptoms are exacerbated during drug binges that can last for days, during which time large quantities of the drug are consumed.

Methamphetamine users may become preoccupied with their own thought patterns, and their actions can become compulsive and nonsensical. For example, a patient may become obsessed with an object of no specific value in his (her) environment, such as a doorknob or a cloud. Patients also may become suspicious of their friends and family members or think that police officers are after them. Less commonly, a patient also may suffer from poverty of speech, psychomotor retardation, and diminished social engagement similar to that reported in some patients with schizophrenia with deficit syndrome. Usually, acute symptoms will last 4 to 7 days after drug cessation, and then resolve completely with protracted abstinence from the drug.

Neurologic signs of methamphetamine use include hemorrhagic strokes in young people without any evidence of previous neurologic impairments. Studies have documented similarities between methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity and traumatic brain injury.5 Postmortem studies have reported the presence of arteriovenous malformation in some patients with hemorrhagic strokes.

Hyperthermia is a dangerous acute effect of methamphetamine use. High body temperatures can cause both peripheral and central abnormalities, including muscular and cardiovascular dysfunction, renal failure secondary to rhabdomyolysis, heat stroke, and other heat-induced malignant syndromes. Some of the central dysfunctions may be related to heat-induced production of free radicals in various brain regions. There are no pharmacologic treatments for methamphetamine-induced thermal dysregulation.6 Therefore, clinicians need to focus on reducing body temperature by using cooling fans or cold water baths. Efforts should be made to avoid overhydrating patients because of the risk of developing the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion.

Chronic methamphetamine abuse

Psychosis is a long-term complication of chronic abuse of the drug.7 Although psychosis has been a reported complication of methamphetamine use since the 1950s,8 most of the subsequent literature is from Japan, where methamphetamine use was highly prevalent after World War II.9,10 The prevalence of methamphetamine-induced psychosis in methamphetamine-dependent patients varies from 13% (in the United States11) to 50% (in Asia12). This difference might be related to variability in the purity of methamphetamine used in different locations.

Methamphetamine users may experience a pre-psychotic state that consists of ideas of reference and delusional moods. This is followed by a psychotic state that includes hallucinations and delusions. The time it takes to develop these symptoms can vary from a few months up to >20 years after starting to use methamphetamine.10,13 Psychosis can occur in patients who do not have a history of psychiatric illness.10

The clinical presentation of methamphetamine-induced psychosis includes delusions of reference and persecutions.8-10 Paranoid delusions may be accompanied by violent behavior. Some patients may present with grandiose or jealousy delusions. Patients may experience auditory, tactile, or visual hallucinations. They may exhibit mania and logorrheic verbal outputs, symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of methamphetamine-induced mood disorder with manic features. Patients who use large daily doses of the drug also may report that there are ants or other parasites crawling under their skin (eg, formication, “meth mites”) and might present with infected excoriations of their skin as a result of attempting to remove insects. This is clinically important because penicillin-resistant bacteria are common in patients who use methamphetamine, and strains tend to be virulent.

Psychotic symptoms can last from a few days to several weeks after stopping methamphetamine use, although methamphetamine-induced psychosis can persist after long periods of abstinence.14 Psychotic symptoms may recur with re-exposure to the drug9 or repeated stressful life events.15 Patients with recurrent psychosis in the absence of a drug trigger appear to have high levels of peripheral norepinephrine.15 Patients with psychosis caused by long-term methamphetamine use will not necessarily show signs of sympathomimetic dysfunction because they may not have any methamphetamine in the body when they first present for clinical evaluation. Importantly, patients with methamphetamine-induced psychosis have been reported to have poor outcomes at follow-up.16 They have an increased risk of suicide, recurrent drug-induced psychosis, and comorbid alcohol abuse.16

Doses required to induce psychosis vary from patient to patient and may depend on the patient’s genetic background and/or environmental conditions. Methamphetamine can increase the severity of many psychiatric symptoms17 and may expedite the development of schizophrenia in first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia.18

The diagnosis of methamphetamine-induced psychosis should focus on differentiating it from schizophrenia. Wang et al19 found similar patterns of delusions in patients with schizophrenia and those with methamphetamine-induced psychosis. However, compared with patients with schizophrenia, patients with methamphetamine-induced psychosis have a higher prevalence of visual and tactile hallucinations, and less disorganization, blunted affect, and motor retardation. Some patients may present with depression and suicidal ideation; these features may be more prominent during withdrawal, but also may be obvious during periods of active use.16

Although these clinical features may be helpful initially, more comparative neurobiologic investigations are needed to identify potential biologic differences between schizophrenia and methamphetamine-induced psychosis because these differences will impact therapeutic approaches to these diverse population groups.

Neurologic complications. Chronic methamphetamine users may develop various neurologic disorders.20 They may present with stereotypies involving finger movements or repeated rubbing of mouth or face, orofacial dyskinesia, and choreoathetoid movements reminiscent of classical neurologic disorders. These movement disorders can persist after cessation of methamphetamine use. In some cases, these movement abnormalities may respond to dopamine receptor antagonists such as haloperidol.

Neuropsychological findings. Chronic methamphetamine users show mild signs of cognitive decline that affects a broad range of neuropsychological functions.21-23 There are deficits in several cognitive processes that are dependent on the function of frontostriatal and limbic circuits.24-26 Specifically, episodic memory, executive functions, complex information processing speed, and psychomotor functions all have been reported to be negatively impacted.

Methamphetamine use often results in psychiatric distress that impacts users’ interpersonal relationships.27 Additionally, impulsivity may exacerbate their psychosocial difficulties and promote maintenance of drug-seeking behaviors.28 Cognitive deficits lead to poor health outcomes, high-risk behaviors, employment difficulties, and repeated relapse.29,30

Partial recovery of neuropsychological functioning and improvement in affective distress can be achieved after sustained abstinence from methamphetamine, but recovery may not be complete. Because cognitive dysfunction can influence treatment outcomes, clinicians need to be fully aware of the cognitive status of those patients, and a thorough neuropsychological evaluation is necessary before initiating treatment.

Treatment

Methamphetamine abuse. Because patients who abuse methamphetamine are at high risk of developing psychosis, neurologic complications, and neuropsychological disorders, initiating treatment early in the course of their addiction is of paramount importance. Treatment of methamphetamine addiction is complicated by the fact that these patients have a high prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders, which clinicians need to keep in mind when selecting therapeutic interventions.

There are no FDA-approved agents for treating methamphetamine abuse.31 Several drugs have been tried with varying degrees of success, including bupropion, modafinil, and naltrexone. A study of modafinil found no clinically significant effects for treating methamphetamine abuse; however, only approximately one-half of participants in this study took modafinil as instructed.32 Certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, including fluoxetine and paroxetine, have not been shown to be effective in treating these patients. Naltrexone may be a reasonable medication to consider because of the high prevalence of comorbid alcohol abuse among methamphetamine users.

Other treatments for methamphetamine addiction consist of behavioral interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy. Clinical experience has shown that the risk of relapse depends on how long the patient has been abstinent prior to entering a treatment program, the presence of attention and memory deficits, and findings of poor decision-making on neuropsychological tests.

The presence of cognitive abnormalities has been reported to impact methamphetamine abusers’ response to treatment.33 These findings suggest the need to develop approaches that might improve cognition in patients who are undergoing treatment for methamphetamine abuse. The monoaminergic agent modafinil and similar drugs need to be evaluated in large populations to increase the possibility of identifying characteristics of patients who might respond to cognitive enhancement.34

Methamphetamine-induced psychosis. First-generation antipsychotics, such as haloperidol or fluphenazine, need to be used sparingly in patients with methamphetamine-induced psychosis because of the risk of developing extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and because these patients are prone to develop motor complications as a result of methamphetamine abuse. Second-generation antipsychotics, such as risperidone and olanzapine, may be more appropriate because of the lower risks of EPS.35 The presence of high norepinephrine levels in some patients with recurrent methamphetamine psychosis suggests that drugs that block norepinephrine receptors, such as prazosin or propranolol, might be of therapeutic benefit if they are shown to be effective in controlled clinical trials.

1. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2016. United Nations publication, Sales No. E.16.XI.7. http://www.unodc.org/wdr2016. Published 2016. Accessed September 28, 2017.

2. Krasnova IN, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine toxicity and messengers of death. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60(2):379-407.

3. Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(8):760-773.

4. Cadet JL, Bisagno V, Milroy CM. Neuropathology of substance use disorders. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(1):91-107.

5. Gold MS, Kobeissy FH, Wang KK, et al. Methamphetamine- and trauma-induced brain injuries: comparative cellular and molecular neurobiological substrates. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(2):118-127.

6. Gold MS, Graham NA, Kobeissy FH, et al. Speed, cocaine, and other psychostimulants death rates. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(7):1184.

7. Shelly J, Uhlmann A, Sinclair H, et al. First-rank symptoms in methamphetamine psychosis and schizophrenia. Psychopathology. 2016;49(6):429-435.

8. Connell PH. Amphetamine psychosis. In: Connell PH. Maudsley monographs. No. 5. London, United Kingdom: Oxford Press; 1958:5.

9. Sato M. A lasting vulnerability to psychosis in patients with previous methamphetamine psychosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;654(1):160-170.

10. Ujike H, Sato M. Clinical features of sensitization to methamphetamine observed in patients with methamphetamine dependence and psychosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1025(1):279-287.

11. Glasner-Edwards S, Mooney LJ, Marinelli-Casey P, et al; Methamphetamine Treatment Project Corporate Authors. Psychopathology in methamphetamine-dependent adults 3 years after treatment. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(1):12-20.

12. Sulaiman AH, Said MA, Habil MH, et al. The risk and associated factors of methamphetamine psychosis in methamphetamine-dependent patients in Malaysia. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(suppl 1):S89-S94.

13. Fasihpour B, Molavi S, Shariat SV. Clinical features of inpatients with methamphetamine-induced psychosis. J Ment Health. 2013;22(4):341-349.

14. Akiyama K, Saito A, Shimoda K. Chronic methamphetamine psychosis after long-term abstinence in Japanese incarcerated patients. Am J Addict. 2011;20(3):240-249.

15. Yui K, Goto K, Ikemoto S, et al. Methamphetamine psychosis: spontaneous recurrence of paranoid-hallucinatory states and monoamine neurotransmitter function. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17(1):34-43.

16. Kittirattanapaiboon P, Mahatnirunkul S, Booncharoen H, et al. Long-term outcomes in methamphetamine psychosis patients after first hospitalisation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(4):456-461.

17. McKetin R, Dawe S, Burns RA, et al. The profile of psychiatric symptoms exacerbated by methamphetamine use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161:104-109.

18. Li H, Lu Q, Xiao E, et al. Methamphetamine enhances the development of schizophrenia in first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(2):107-113.

19. Wang LJ, Lin SK, Chen YC, et al. Differences in clinical features of methamphetamine users with persistent psychosis and patients with schizophrenia. Psychopathology. 2016;49(2):108-115.

20. Rusyniak DE. Neurologic manifestations of chronic methamphetamine abuse. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36(2):261-275.

21. Simon SL, Domier C, Carnell J, et al. Cognitive impairment in individuals currently using methamphetamine. Am J Addict. 2000;9(3):222-231.

22. Paulus MP, Hozack NE, Zauscher BE, et al. Behavioral and functional neuroimaging evidence for prefrontal dysfunction in methamphetamine-dependent subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26(1):53-63.

23. Rendell PG, Mazur M, Henry JD. Prospective memory impairment in former users of methamphetamine. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009;203(3):609-616.

24. Monterosso JR, Ainslie G, Xu J, et al. Frontoparietal cortical activity of methamphetamine-dependent and comparison subjects performing a delay discounting task. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007;28(5):383-393.

25. Nestor LJ, Ghahremani DG, Monterosso J, et al. Prefrontal hypoactivation during cognitive control in early abstinent methamphetamine-dependent subjects. Psychiatry Res. 2011;194(3):287-295.

26. Scott JC, Woods SP, Matt GE, et al. Neurocognitive effects of methamphetamine: a critical review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev. 2007;17(3):275-297.

27. Cretzmeyer M, Sarrazin MV, Huber DL, et al. Treatment of methamphetamine abuse: research findings and clinical directions. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24(3):267-277.

28. Semple SJ, Zians J, Grant I, et al. Impulsivity and methamphetamine use. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;29(2):85-93.

29. Hester R, Lee N, Pennay A, et al. The effects of modafinil treatment on neuropsychological and attentional bias performance during 7-day inpatient withdrawal from methamphetamine dependence. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;18(6):489-497.

30. Weber E, Blackstone K, Iudicello JE, et al; Translational Methamphetamine AIDS Research Center (TMARC) Group. Neurocognitive deficits are associated with unemployment in chronic methamphetamine users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125(1-2):146-153.

31. Ballester J, Valentine G, Sofuoglu M. Pharmacological treatments for methamphetamine addiction: current status and future directions. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2017;10(3):305-314.

32. Anderson AL, Li SH, Biswas K, et al. Modafinil for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120(1-3):135-141.

33. Cadet JL, Bisagno V. Neuropsychological consequences of chronic drug use: relevance to treatment approaches. Front Psychiatry. 2016;6:189.

34. Loland CJ, Mereu M, Okunola OM, et al. R-modafinil (armodafinil): a unique dopamine uptake inhibitor and potential medication for psychostimulant abuse. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(5):405-413.

35. Farnia V, Shakeri J, Tatari F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of aripiprazole versus risperidone for the treatment of amphetamine-induced psychosis. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40(1):10-15.

1. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2016. United Nations publication, Sales No. E.16.XI.7. http://www.unodc.org/wdr2016. Published 2016. Accessed September 28, 2017.

2. Krasnova IN, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine toxicity and messengers of death. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60(2):379-407.

3. Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(8):760-773.

4. Cadet JL, Bisagno V, Milroy CM. Neuropathology of substance use disorders. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127(1):91-107.

5. Gold MS, Kobeissy FH, Wang KK, et al. Methamphetamine- and trauma-induced brain injuries: comparative cellular and molecular neurobiological substrates. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66(2):118-127.

6. Gold MS, Graham NA, Kobeissy FH, et al. Speed, cocaine, and other psychostimulants death rates. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(7):1184.

7. Shelly J, Uhlmann A, Sinclair H, et al. First-rank symptoms in methamphetamine psychosis and schizophrenia. Psychopathology. 2016;49(6):429-435.

8. Connell PH. Amphetamine psychosis. In: Connell PH. Maudsley monographs. No. 5. London, United Kingdom: Oxford Press; 1958:5.

9. Sato M. A lasting vulnerability to psychosis in patients with previous methamphetamine psychosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;654(1):160-170.

10. Ujike H, Sato M. Clinical features of sensitization to methamphetamine observed in patients with methamphetamine dependence and psychosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1025(1):279-287.

11. Glasner-Edwards S, Mooney LJ, Marinelli-Casey P, et al; Methamphetamine Treatment Project Corporate Authors. Psychopathology in methamphetamine-dependent adults 3 years after treatment. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(1):12-20.

12. Sulaiman AH, Said MA, Habil MH, et al. The risk and associated factors of methamphetamine psychosis in methamphetamine-dependent patients in Malaysia. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(suppl 1):S89-S94.

13. Fasihpour B, Molavi S, Shariat SV. Clinical features of inpatients with methamphetamine-induced psychosis. J Ment Health. 2013;22(4):341-349.

14. Akiyama K, Saito A, Shimoda K. Chronic methamphetamine psychosis after long-term abstinence in Japanese incarcerated patients. Am J Addict. 2011;20(3):240-249.

15. Yui K, Goto K, Ikemoto S, et al. Methamphetamine psychosis: spontaneous recurrence of paranoid-hallucinatory states and monoamine neurotransmitter function. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17(1):34-43.

16. Kittirattanapaiboon P, Mahatnirunkul S, Booncharoen H, et al. Long-term outcomes in methamphetamine psychosis patients after first hospitalisation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(4):456-461.

17. McKetin R, Dawe S, Burns RA, et al. The profile of psychiatric symptoms exacerbated by methamphetamine use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161:104-109.

18. Li H, Lu Q, Xiao E, et al. Methamphetamine enhances the development of schizophrenia in first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(2):107-113.

19. Wang LJ, Lin SK, Chen YC, et al. Differences in clinical features of methamphetamine users with persistent psychosis and patients with schizophrenia. Psychopathology. 2016;49(2):108-115.

20. Rusyniak DE. Neurologic manifestations of chronic methamphetamine abuse. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2013;36(2):261-275.

21. Simon SL, Domier C, Carnell J, et al. Cognitive impairment in individuals currently using methamphetamine. Am J Addict. 2000;9(3):222-231.

22. Paulus MP, Hozack NE, Zauscher BE, et al. Behavioral and functional neuroimaging evidence for prefrontal dysfunction in methamphetamine-dependent subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26(1):53-63.

23. Rendell PG, Mazur M, Henry JD. Prospective memory impairment in former users of methamphetamine. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009;203(3):609-616.

24. Monterosso JR, Ainslie G, Xu J, et al. Frontoparietal cortical activity of methamphetamine-dependent and comparison subjects performing a delay discounting task. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007;28(5):383-393.

25. Nestor LJ, Ghahremani DG, Monterosso J, et al. Prefrontal hypoactivation during cognitive control in early abstinent methamphetamine-dependent subjects. Psychiatry Res. 2011;194(3):287-295.

26. Scott JC, Woods SP, Matt GE, et al. Neurocognitive effects of methamphetamine: a critical review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rev. 2007;17(3):275-297.

27. Cretzmeyer M, Sarrazin MV, Huber DL, et al. Treatment of methamphetamine abuse: research findings and clinical directions. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24(3):267-277.

28. Semple SJ, Zians J, Grant I, et al. Impulsivity and methamphetamine use. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;29(2):85-93.

29. Hester R, Lee N, Pennay A, et al. The effects of modafinil treatment on neuropsychological and attentional bias performance during 7-day inpatient withdrawal from methamphetamine dependence. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;18(6):489-497.

30. Weber E, Blackstone K, Iudicello JE, et al; Translational Methamphetamine AIDS Research Center (TMARC) Group. Neurocognitive deficits are associated with unemployment in chronic methamphetamine users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125(1-2):146-153.

31. Ballester J, Valentine G, Sofuoglu M. Pharmacological treatments for methamphetamine addiction: current status and future directions. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2017;10(3):305-314.

32. Anderson AL, Li SH, Biswas K, et al. Modafinil for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120(1-3):135-141.

33. Cadet JL, Bisagno V. Neuropsychological consequences of chronic drug use: relevance to treatment approaches. Front Psychiatry. 2016;6:189.

34. Loland CJ, Mereu M, Okunola OM, et al. R-modafinil (armodafinil): a unique dopamine uptake inhibitor and potential medication for psychostimulant abuse. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(5):405-413.

35. Farnia V, Shakeri J, Tatari F, et al. Randomized controlled trial of aripiprazole versus risperidone for the treatment of amphetamine-induced psychosis. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2014;40(1):10-15.