User login

- Consider using the Headache Assessment Quiz, which 76% of providers in this study said enabled patients to adequately convey headache severity/symptoms, compared with just 20% of providers at baseline who thought patients communicated clearly.

- Use the quiz also to better understand the impact of migraine on a patient’s life, and to help determine which patients need migraine-specific therapy.

Up to 25% of patients in a typical primary care practice could be afflicted with migraine, and many of them simply do not report their headaches. Their silence does not necessarily imply adequate control with self-medication. Other concerns may command their attention, or inadequate communication may mask the issue. Whatever the reason, too few of them receive migraine-specific medications and proper instruction on avoiding headache triggers that could relieve the well-known burden of this disorder. Our study verifies the success of a program for screening—including a Headache Assessment Quiz—and treating migraine that also eases the burden of management for you.

For more original research on the treatment of migraines, see “Do family physicians fail to provide triptans for patients with migraine?”

We begin with a summary of our findings, and then give a detailed account of our study methods and results.

How many patients are slipping through the cracks?

Nearly half of all persons with migraine in the United States have not received a diagnosis for their disorder.1 Many of them suffer substantial functional impairment in daily activities and, thus, a diminished quality of life.

What’s to blame for this underdiagnosis? Perhaps a person’s failure to consult a physician for headache, poor patient-physician communication, comorbid conditions that obscure the presence or significance of headache, or a lack of time and resources devoted to detecting and managing migraine in the health care setting.2-5 In 2 recent studies conducted mainly in primary care settings, the frequency of unrecognized migraine among patients consulting for headache ranged from 48% to 60%.6,7

Even when migraine is recognized, quality of care is often suboptimal. In 1999, only 4 of 10 US migraineurs used prescription medication for migraine.6 In a recently published study that used 2002–2003 retrospective data from more than 30 managed care organizations, 50% of patients with a migraine diagnosis who had prescription drug coverage filled a prescription for a medication commonly used to treat migraine.8

We need a reliable system for migraine detection and management.

Migraine Care Program proves its worth

The Migraine Care Program (at www.migrainecareprogram.com) is a disease-management program employing educational materials and clinical assessment tools to help health care providers and patients improve awareness and recognition of migraine and the quality of care received by migraine sufferers. Components of the program:

- Informational modules on migraine epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, triggers, impact, and treatment

- Headache diary for patients

- Action plan for patients to complete with their health care providers

- Information for patients on effectively communicating with their health care providers about headache

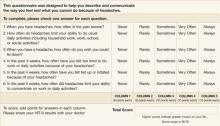

- 10-question Headache Assessment Quiz and its supplement, which screen for the presence of migraine (FIGURE 1)

- 6-item Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) (FIGURE 2), a reliable, valid measure of the impact of headache on patients’ lives.9

This article reports the results of a prospective, two-phase study undertaken to assess (Phase 1) the utility of the Headache Assessment Quiz in facilitating recognition of migraine; and (Phase 2) the usefulness of the Migraine Care Program from the perspectives of both primary care providers and their patients. The study is unique in being one of a few to assess the effectiveness of a disease management program in improving patient outcomes or influencing physician’s behavior.

FIGURE 1

Headache Assessment Quiz

FIGURE 2

Headache Impact Test: HIT-6 (version 1.0)

How we measured success

In our study, primary care providers using the Migraine Care Program’s Headache Assessment Quiz as a screening tool diagnosed migraine in 25% of 4443 patients. That 1 in 4 patients consulting these primary care clinics for any reason had migraine is consistent with the estimated prevalence of migraine in the general population.1 More than half (52%) of those given a clinical diagnosis of migraine in this study had not previously received the diagnosis, which is also consistent with previous figures on unrecognized migraine.1,6,7 This pattern of results suggests that provider education and use of the Headache Assessment Quiz facilitated recognition of migraine in this sample.

Providers said the Headache Assessment Quiz improved management decisions. Three of 4 (74%) patients who tested positive for migraine on the Headache Assessment Quiz were subsequently given a clinical diagnosis of migraine after further evaluation by the primary care provider. Providers’ ratings of the Headache Assessment Quiz indicate the tool proved useful in multiple aspects of migraine care: understanding headache severity and impact, facilitating treatment decisions, and identifying patients requiring treatment. By the end of the study, providers found headache patients less difficult to assess and manage than before.

Clear benefits to patients. For 42% of patients with migraine, providers adjusted the pre-study medication regimens—most often by adding a migraine-specific triptan. On post-study surveys, significantly more patients said they were satisfied or very satisfied with the effectiveness of medication and with the overall quality of migraine care compared with the beginning of the study. The impact of headache on patients’ lives as determined from HIT-6 scores was less at the end of the study compared with the beginning.

A subgroup analysis among Phase 2 patients confirmed the value of the program. Phase 2 patients reporting no pre-study diagnosis of migraine were significantly less satisfied with care and medication at baseline than patients reporting a pre-study migraine diagnosis—even though patients reporting no pre-study diagnosis had less severe migraine at baseline. Patients with previously unrecognized migraine responded well to care in our study. Though satisfaction increased and headache impact decreased from baseline to the end of Phase 2 for both sets of patients, improvement was greater for those without a prior diagnosis.

Migraine affects 18% of women and 7% of men in the United States.1 A large body of research conducted over the past decade contradicts the historical conception of migraine as a trivial illness and has established it as a disabling condition warranting aggressive management.10-13 Concurrently, understanding of the pathophysiology of migraine has evolved; and new, migraine-specific treatments that can relieve pain and restore patients’ functional ability have been introduced.14,15 Despite these advances, several barriers to optimizing migraine care remain. Perhaps the most significant obstacle to effective migraine care, failure to recognize and diagnose migraine occurs alarmingly often.2,6,7,16,17 In a 1999 US population-based survey, less than half (48%) of those meeting International Headache Society (IHS) diagnostic criteria for migraine reported having received a physician diagnosis of migraine.1 Frequency of physician diagnosis of migraine in 1999 did not increase appreciably from diagnosis rates in 1989 although consultations for headache tripled over the 10-year period. Underrecognition and suboptimal management of migraine may be particularly problematic in the primary care setting, where the majority of migraine sufferers consult.

The suboptimal nature of migraine care is also reflected in patients’ assessments of medical care. In a recent study of patients with primary headache diagnoses in three geographically diverse primary care institutions in the United States, 1 of 4 patients with severe headaches reported dissatisfaction with their headache care; and 3 of 4 reported moderate or severe problems with headache management.18

Limitations of the study. First, patients were enrolled only if they agreed to complete the Headache Assessment Quiz. Thus, regarding characteristics relevant to study assessments, selection bias may have occurred if patients who agreed to take the quiz differed systematically from those who did not.

Second, attrition during Phase 2—though relatively low for a naturalistic study that, unlike a clinical trial, did not use incentives such as provision of study medication—might have biased the results of patient assessments at the end of the study. Attrition could have inflated the patient-satisfaction and other end-of-study ratings of medication and migraine care if dissatisfied patients were more likely to withdraw prematurely from the study than were satisfied patients.

Third, the study lacked a control group because of the difficulty in blinding investigators in a naturalistic study.

Strengths of the study. Among several disease management programs for migraine, the Migraine Care Program is unique in being one of the few whose effects on migraine care have been assessed. In this study, application of the Migraine Care Program was evaluated in the “real-world” clinical setting and as used by providers (physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants) typically responsible for headache care in primary care centers across the US. These characteristics enhance the probability that the results reflect those achievable in actual clinical practice. The comprehensive nature of the study assessments, which involved both primary care providers and patients, supports the benefits of the program.

Methods

This prospective, observational study had 2 phases. During Phase 1, primary care providers were introduced to the Migraine Care Program, and they administered the Headache Assessment Quiz to consulting patients who agreed to complete it. During Phase 2, a subset of patients who screened positive for migraine on the Headache Assessment Quiz in Phase 1 and whose migraine diagnosis was confirmed by their primary care provider received 12 weeks of additional treatment for migraine under the care of that primary care provider.

Participants

Study participants included both primary care providers and their patients. Eligible health care providers included physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants responsible for performing headache assessments in US primary care practices that did not routinely use a questionnaire to screen headache patients prior to the study.

Eligible patients for Phase 1 were the first 100 consecutive 18- to 65-year-old patients in each practice who agreed to complete the Headache Assessment Quiz. Patients were eligible for Phase 1 regardless of whether they were consulting for headache. Patients from Phase 1 were eligible for Phase 2 if they screened positive for migraine on the Headache Assessment Quiz, had a confirmed clinical diagnosis of migraine meeting IHS criteria 1.1 or 1.2,19 and were willing to remain under the care of the study investigator and to treat headaches with therapy recommended by that investigator for 12 weeks.

Procedures

Phase 1

Primary care providers completed an Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education-accredited educational program consisting of a 38-minute DVD on migraine diagnosis and screening. After they completed the educational program, health care providers administered the Headache Assessment Quiz and HIT-6 to a target of 100 consecutively consulting patients regardless of patients’ reason for consulting. For patients who screened positive for migraine on the Headache Assessment Quiz, primary care providers recorded whether or not in their clinical judgment they confirmed a diagnosis of migraine by IHS criteria19 and whether or not patients reported, in response to a question, that they had received a migraine diagnosis from a health care professional before the study.

Phase 2

Primary care providers were asked to recruit up to 10 Phase-1 patients with a confirmed clinical diagnosis of migraine for Phase 2 of the study. At least half of the patients recruited in each practice were to have received their first clinical diagnosis of migraine during the study. All patients provided written, informed consent to participate in Phase 2.

At the beginning of Phase 2, eligible patients received Migraine Care Program educational materials including a migraine diary and a pamphlet about the causes, triggers, symptoms of migraine, and migraine types. They received migraine care for the ensuing 12 weeks under the supervision of the investigator. Investigators could prescribe any pharmacological or nonpharmacological migraine treatment to patients at their discretion.

Measures

In questionnaires administered at the beginning of the study before they initiated the Migraine Care Program (baseline) and again at the end of Phase 2, primary care providers rated the difficulty of assessing and treating patients with headache (0 = not at all difficult; 10 = extremely difficult), the importance of understanding the impact of headaches on a patient’s life when making treatment decisions (on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from very important to very unimportant), and their satisfaction (on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from very satisfied to very dissatisfied) with how well patients describe their headache severity and how well patients describe the physical, emotional, and financial impact of headaches.

For the questions on patient communication about headaches, providers were instructed to respond with respect to their general experience with patients for the baseline questionnaire and with respect to their experience with patients in Phase 2 of the study for the end-of-study questionnaire. The end-of-study questionnaire also contained items on which primary care providers rated satisfaction with the use of the Headache Assessment Quiz to facilitate (a) understanding of the impact of headaches on patients’ lives; (b) treatment decisions; and (c) identification of headache patients requiring better treatment and indicated whether or not they would recommend the Headache Assessment Quiz for use in clinical practice.

In questionnaires administered at the beginning of Phase 2 and again at the end of the study, patients who participated in Phase 2 rated their satisfaction (on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from very satisfied to very dissatisfied) with the medication used to treat migraine headaches and with the quality of medical care received for migraine. In addition, patients rated the bothersomeness of side effects of medication used to treat migraine headaches (on a 5-point categorical scale ranging from not at all to extremely). At the beginning of Phase 2, patients listed the medications they had used during the 3 months before the study to treat headaches. HIT-6, which was first administered at study entry, was also administered at the end of Phase 2.

Responses to the primary care provider and patient questionnaires were summarized with descriptive statistics. The Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test was used to compare differences between baseline and the end of the study in the distribution of percentages of respondents to each question on satisfaction, bothersomeness, and importance; in median primary care provider ratings of difficulty of assessing and treating headache patients; and in distribution of HIT-6 scores (<50 = little to no impact of headache; 50–55 = some impact; 56–59 = substantial impact; ≥60 = severe impact).

In a subgroup analysis, baseline characteristics and end-of-study assessments were summarized separately for Phase 2 patients who reported a pre-study diagnosis of migraine and those who reported no pre-study diagnosis of migraine. Differences between subgroups were compared with chi-square tests as appropriate.

Results

Phase 1 participants

Forty-nine primary care providers (physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) participated in the Migraine Care Program (TABLE 1). Providers’ mean age was 44 years (SD=8.28). The majority (86%) were in group practice. The number of patients recruited to complete the Headache Assessment Quiz during Phase 1 of the study was 4443.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of study participants

| PRIMARY CARE PROVIDERS | |

| N | 49 |

| Type of provider, % | |

| Physician | 84 |

| Nurse practitioner | 100 |

| Physician assistant | 6 |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 44 (8.3) |

| Female, % | 33 |

| Practice type, % | |

| Group | 86 |

| Private | 14 |

| PATIENTS: PHASE 2 | |

| N | 470 |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 41 (11.9) |

| Female, % | 77 |

| Race, % | |

| White | 85 |

| Black | 6 |

| Hispanic | 6 |

| Other | 2† |

| Medications used for headache during the 3 months before the study,* % | |

| Over-the-counter medications | 70 |

| Triptans | 19 |

| Prescription NSAIDs | 14 |

| Combination analgesic | 9 |

| Narcotics | 5 |

| *Patients could list more than one medication. | |

| †Does not add to 100% because patients could have taken multiple medications. | |

Migraine diagnosis during Phase 1

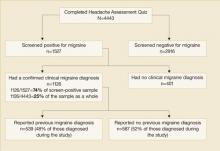

Of the 4443 patients who completed the Headache Assessment Quiz in Phase 1, 1527 (34%) screened positive for migraine. Of these 1527 patients who screened positive for migraine, 1126 (74% of the 1527 patients screening positive for migraine) had their diagnosis confirmed during further evaluation by their primary care provider (FIGURE 3). More than half (52%) of the 1126 patients with a confirmed migraine diagnosis reported that they had not received a health care professional’s diagnosis of migraine prior to the study.

The proportion of patients with migraine as confirmed by a clinical migraine diagnosis was 25% (1126/4443) in the sample as a whole, which included all patients who had consulted these primary care practices for any reason and who had agreed to complete the Headache Assessment Quiz.

FIGURE 3

Prevalence of migraine among patients who consulted primary care providers for any reason and who agreed to complete the Headache Assessment Quiz

PCP’s perceptions of headache management before and after participation in the program

Primary care providers’ participation in the Migraine Care Program was associated with an increase in awareness of headache impact. At the end of Phase 2 compared with the beginning of the study, significantly more providers rated understanding headache impact as being important or very important in treatment decisions (87% vs 74%; P<.05) (TABLE 2).

Primary care providers’ participation in the Migraine Care Program was also associated with a perceived reduction in the challenges of providing headache care. At the end of Phase 2 compared with the beginning of the study, primary care providers reported assessing and treating headache to be significantly less difficult (median score = 6 at baseline and 3 at the end of the study; P<.001) (TABLE 2).

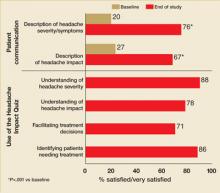

This improvement was accompanied by the perception of better patient communication about headaches: the proportions of primary care providers indicating that they were satisfied or very satisfied with patients’ descriptions of headache severity/symptoms and headache impact were significantly higher for patients they treated in Phase 2 than for headache patients they had treated prior to the study (76% vs 20% for severity/symptoms; 67% vs 27% for headache impact; P<.001 for both comparisons) (FIGURE 4).

The majority of providers indicated that they were satisfied or very satisfied with the use of the Headache Assessment Quiz as a tool for each of the dimensions assessed: understanding headache severity (88%), understanding headache impact (78%), making treatment decisions (71%), and identifying patients requiring treatment (86%) (FIGURE 4). Nearly all providers (96%) indicated that they would recommend the Headache Assessment Quiz for use in clinical practice (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Primary care providers’ perceptions of headache management at baseline and at the end of the study after participating in the Migraine Care Program

| BASELINE | END OF STUDY | |

| Knowledge of headache impact is important/very important in making decisions about treatment, % | 74 | 87* |

| Difficulty in headache assessment, median score† (range) | 6 (2–8) | 3‡ (1–7) |

| Would recommend the Headache Assessment Quiz for use in clinical practice, % | NA | 96 |

| *P<.05 vs baseline. | ||

| †Difficulty was scored on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all difficult) to 10 (extremely difficult). | ||

| ‡P<.001 vs baseline. | ||

FIGURE 4

Percentages of primary care providers who were satisfied/very satisfied with patient communication and the use of the Headache Assessment Quiz

Patients’ perceptions of headache care by PCPs participating in the Migraine Care Program

Phase 2 sample. The number of patients who participated in Phase 2 was 470 (TABLE 1). Mean age of patients in the Phase 2 sample was 41 years (SD=11.9). The majority of patients were white (85%) and were women (77%).

Medications

Among the 470 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of migraine who participated in Phase 2, the most common medications used to treat headaches during the 3 months prior to the study were over-the-counter medications (70% of patients) (TABLE 1). Fewer than one in five patients (19%) reported treating their pre-study headaches with migraine-specific triptan therapy.

At the beginning of Phase 2, primary care providers changed the headache medication regimen of 197 of these patients (42%). Of the 205 total changes to medication regimens, 72% involved adding a triptan; 10% involved adding other medications; 11% involved discontinuation of a medication; and 7% involved dose adjustment.

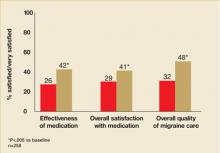

The changes to medication regimens were associated with significant improvement in satisfaction with medication in the subset of patients who finished Phase 2 and completed the end-of-study questionnaire (n=258). More patients indicated that they were satisfied or very satisfied with the effectiveness of headache medications used during the study than with headache medications used before the study (42% versus 26%; P<.005) (FIGURE 5). In addition, with respect to overall satisfaction with medication, more patients reported themselves to be satisfied or very satisfied with the medications used during the study than with those used before the study (41% vs 29%; P<.005) (FIGURE 5). Bothersomeness of side effects of migraine medication did not differ during the study versus before the study. Most patients (63%) reported themselves to be not at all bothered by medication side effects both during the study and before the study.

FIGURE 5

Percentage of patients who were satisfied/very satisfied with medication and migraine care

Quality of care

The proportion of patients indicating that they were satisfied or very satisfied with the overall quality of migraine care was significantly higher for care received during the study than care received before the study (48% vs 32%; P<.001) (FIGURE 5).

Impact of headache

Patients’ HIT-6 scores reflected significantly less impact of headache at the end of Phase 2 compared with the beginning of the study. The percentage of patients whose headaches impacted their lives substantially or very severely was 75.3% at enrollment compared with 68.8% at the end of the study (P<.05).

Patients with pre-study migraine diagnosis vs those without

Of the 470 patients in the Phase 2 sample, 230 reported a pre-study diagnosis of migraine and 240 report no pre-study diagnosis of migraine. Patients who reported a pre-study migraine diagnosis compared with those who did not appeared to have more severe migraine at baseline as reflected by a higher frequency of severe pain, a longer duration of typical migraine attacks, and higher frequency of HIT-6 scores reflecting substantial or very severe impact of headaches (TABLE 3).

Patients with no prior diagnosis were significantly less satisfied with care and medication at baseline than patients with a prior diagnosis. While satisfaction increased and headache impact decreased from baseline to the end of Phase 2 both in patients who reported a prior diagnosis and those who did not, improvement was greater in those without a prior diagnosis (TABLE 3).

Acknowledgments

Some of the data described in this manuscript were presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the American Headache Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. The study described in this manuscript was funded by GlaxoSmithKline. The authors acknowledge Jane Saiers, PhD, for assistance with writing the manuscript. Dr. Saiers’ work on the manuscript was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

CORRESPONDENCE

Stephen Landy, MD, Wesley Headache Clinic, 8974 Bridge Forest Drive, Memphis, TN 38138. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, et al. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache 2001;41:646-657.

2. De Diego EV, Lanteri-Minet M. Recognition and management of migraine in primary care: influence of functional impact measured by the Headache Impact Test (HIT). Cephalalgia 2005;25:184-190.

3. Hu XH, Markson LE, Lipton RB, et al. Burden of migraine in the United States: Disability and economic costs. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:813-815.

4. Blau JN, MacGregor EA. Migraine consultations: A triangle of viewpoints. Headache 1995;35:104-106.

5. MacGregor EA. The doctor and the migraine patient: Improving compliance. Neurology 1997;48(suppl 3):S16-S20.

6. Lipton RB, Diamond S, Reed M, Diamond ML, Stewart WF. Migraine diagnosis and treatment: results from the American Migraine Study II. Headache 2001;41:638-645.

7. Tepper SJ, Dahlöf CG, Dowson A, et al. Prevalence and diagnosis of migraine in patients consulting their physician with a complaint of headache: data from the Landmark Study. Headache 2004;44:856-864.

8. Tepper SJ, Martin V, Burch SP, et al. Acute headache treatments in patients with health care coverage: What prescriptions are doctors writing? Headache Pain 2006;17:11-17.

9. Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, Bjorner JB, et al. Six-item short-form survey for measuring headache impact: the HIT-6. Qual Life Res 2003;2:963-974.

10. Matchar DB, Young WB, Rosenberg JH, et al. Multispecialty consensus on diagnosis and treatment of headache: pharmacological management of acute attacks. Neurology 2000;54.:Available at www.aan.com/public/practiceguidelines/03.pdf. Accessed 16 February 2002.

11. Mannix LK. Epidemiology and impact of primary headache disorders. Med Clin North Am 2001;85:887-895.

12. Dowson AJ. Assessing the impact of migraine. Curr Med Res Opin 2001;17:298-309.

13. Stang P, Cady R, Batenhorst A, et al. Workplace productivity: A review of the impact of migraine and its treatment. Pharmacoeconomics 2001;19:231-244.

14. Hargreaves RJ, Shepheard SL. Pathophysiology of migraine-new insights. Can J Neurol Sci 1999;26:S12-S19.

15. Freitag FG. Acute treatment of migraine and the role of trip-tans. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2001;1:125-132.

16. Kaniecki RG. Diagnostic challenges in headache: Migraine as the wolf disguised in sheep’s clothing. Neurology 2002;8(suppl 6):S1-S2.

17. Cady R, Dodick DW. Diagnosis and treatment of migraine. Mayo Clin Proc 2002;77:255-261.

18. Harpole LH, Samsa GP, Matchar DB, et al. Burden of illness and satisfaction with care among patients with headache seen in a primary care setting. Headache 2005;5:1048-1055.

19. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders, 2nd ed. Cephalalgia 2004;(suppl 1):9-160.

- Consider using the Headache Assessment Quiz, which 76% of providers in this study said enabled patients to adequately convey headache severity/symptoms, compared with just 20% of providers at baseline who thought patients communicated clearly.

- Use the quiz also to better understand the impact of migraine on a patient’s life, and to help determine which patients need migraine-specific therapy.

Up to 25% of patients in a typical primary care practice could be afflicted with migraine, and many of them simply do not report their headaches. Their silence does not necessarily imply adequate control with self-medication. Other concerns may command their attention, or inadequate communication may mask the issue. Whatever the reason, too few of them receive migraine-specific medications and proper instruction on avoiding headache triggers that could relieve the well-known burden of this disorder. Our study verifies the success of a program for screening—including a Headache Assessment Quiz—and treating migraine that also eases the burden of management for you.

For more original research on the treatment of migraines, see “Do family physicians fail to provide triptans for patients with migraine?”

We begin with a summary of our findings, and then give a detailed account of our study methods and results.

How many patients are slipping through the cracks?

Nearly half of all persons with migraine in the United States have not received a diagnosis for their disorder.1 Many of them suffer substantial functional impairment in daily activities and, thus, a diminished quality of life.

What’s to blame for this underdiagnosis? Perhaps a person’s failure to consult a physician for headache, poor patient-physician communication, comorbid conditions that obscure the presence or significance of headache, or a lack of time and resources devoted to detecting and managing migraine in the health care setting.2-5 In 2 recent studies conducted mainly in primary care settings, the frequency of unrecognized migraine among patients consulting for headache ranged from 48% to 60%.6,7

Even when migraine is recognized, quality of care is often suboptimal. In 1999, only 4 of 10 US migraineurs used prescription medication for migraine.6 In a recently published study that used 2002–2003 retrospective data from more than 30 managed care organizations, 50% of patients with a migraine diagnosis who had prescription drug coverage filled a prescription for a medication commonly used to treat migraine.8

We need a reliable system for migraine detection and management.

Migraine Care Program proves its worth

The Migraine Care Program (at www.migrainecareprogram.com) is a disease-management program employing educational materials and clinical assessment tools to help health care providers and patients improve awareness and recognition of migraine and the quality of care received by migraine sufferers. Components of the program:

- Informational modules on migraine epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, triggers, impact, and treatment

- Headache diary for patients

- Action plan for patients to complete with their health care providers

- Information for patients on effectively communicating with their health care providers about headache

- 10-question Headache Assessment Quiz and its supplement, which screen for the presence of migraine (FIGURE 1)

- 6-item Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) (FIGURE 2), a reliable, valid measure of the impact of headache on patients’ lives.9

This article reports the results of a prospective, two-phase study undertaken to assess (Phase 1) the utility of the Headache Assessment Quiz in facilitating recognition of migraine; and (Phase 2) the usefulness of the Migraine Care Program from the perspectives of both primary care providers and their patients. The study is unique in being one of a few to assess the effectiveness of a disease management program in improving patient outcomes or influencing physician’s behavior.

FIGURE 1

Headache Assessment Quiz

FIGURE 2

Headache Impact Test: HIT-6 (version 1.0)

How we measured success

In our study, primary care providers using the Migraine Care Program’s Headache Assessment Quiz as a screening tool diagnosed migraine in 25% of 4443 patients. That 1 in 4 patients consulting these primary care clinics for any reason had migraine is consistent with the estimated prevalence of migraine in the general population.1 More than half (52%) of those given a clinical diagnosis of migraine in this study had not previously received the diagnosis, which is also consistent with previous figures on unrecognized migraine.1,6,7 This pattern of results suggests that provider education and use of the Headache Assessment Quiz facilitated recognition of migraine in this sample.

Providers said the Headache Assessment Quiz improved management decisions. Three of 4 (74%) patients who tested positive for migraine on the Headache Assessment Quiz were subsequently given a clinical diagnosis of migraine after further evaluation by the primary care provider. Providers’ ratings of the Headache Assessment Quiz indicate the tool proved useful in multiple aspects of migraine care: understanding headache severity and impact, facilitating treatment decisions, and identifying patients requiring treatment. By the end of the study, providers found headache patients less difficult to assess and manage than before.

Clear benefits to patients. For 42% of patients with migraine, providers adjusted the pre-study medication regimens—most often by adding a migraine-specific triptan. On post-study surveys, significantly more patients said they were satisfied or very satisfied with the effectiveness of medication and with the overall quality of migraine care compared with the beginning of the study. The impact of headache on patients’ lives as determined from HIT-6 scores was less at the end of the study compared with the beginning.

A subgroup analysis among Phase 2 patients confirmed the value of the program. Phase 2 patients reporting no pre-study diagnosis of migraine were significantly less satisfied with care and medication at baseline than patients reporting a pre-study migraine diagnosis—even though patients reporting no pre-study diagnosis had less severe migraine at baseline. Patients with previously unrecognized migraine responded well to care in our study. Though satisfaction increased and headache impact decreased from baseline to the end of Phase 2 for both sets of patients, improvement was greater for those without a prior diagnosis.

Migraine affects 18% of women and 7% of men in the United States.1 A large body of research conducted over the past decade contradicts the historical conception of migraine as a trivial illness and has established it as a disabling condition warranting aggressive management.10-13 Concurrently, understanding of the pathophysiology of migraine has evolved; and new, migraine-specific treatments that can relieve pain and restore patients’ functional ability have been introduced.14,15 Despite these advances, several barriers to optimizing migraine care remain. Perhaps the most significant obstacle to effective migraine care, failure to recognize and diagnose migraine occurs alarmingly often.2,6,7,16,17 In a 1999 US population-based survey, less than half (48%) of those meeting International Headache Society (IHS) diagnostic criteria for migraine reported having received a physician diagnosis of migraine.1 Frequency of physician diagnosis of migraine in 1999 did not increase appreciably from diagnosis rates in 1989 although consultations for headache tripled over the 10-year period. Underrecognition and suboptimal management of migraine may be particularly problematic in the primary care setting, where the majority of migraine sufferers consult.

The suboptimal nature of migraine care is also reflected in patients’ assessments of medical care. In a recent study of patients with primary headache diagnoses in three geographically diverse primary care institutions in the United States, 1 of 4 patients with severe headaches reported dissatisfaction with their headache care; and 3 of 4 reported moderate or severe problems with headache management.18

Limitations of the study. First, patients were enrolled only if they agreed to complete the Headache Assessment Quiz. Thus, regarding characteristics relevant to study assessments, selection bias may have occurred if patients who agreed to take the quiz differed systematically from those who did not.

Second, attrition during Phase 2—though relatively low for a naturalistic study that, unlike a clinical trial, did not use incentives such as provision of study medication—might have biased the results of patient assessments at the end of the study. Attrition could have inflated the patient-satisfaction and other end-of-study ratings of medication and migraine care if dissatisfied patients were more likely to withdraw prematurely from the study than were satisfied patients.

Third, the study lacked a control group because of the difficulty in blinding investigators in a naturalistic study.

Strengths of the study. Among several disease management programs for migraine, the Migraine Care Program is unique in being one of the few whose effects on migraine care have been assessed. In this study, application of the Migraine Care Program was evaluated in the “real-world” clinical setting and as used by providers (physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants) typically responsible for headache care in primary care centers across the US. These characteristics enhance the probability that the results reflect those achievable in actual clinical practice. The comprehensive nature of the study assessments, which involved both primary care providers and patients, supports the benefits of the program.

Methods

This prospective, observational study had 2 phases. During Phase 1, primary care providers were introduced to the Migraine Care Program, and they administered the Headache Assessment Quiz to consulting patients who agreed to complete it. During Phase 2, a subset of patients who screened positive for migraine on the Headache Assessment Quiz in Phase 1 and whose migraine diagnosis was confirmed by their primary care provider received 12 weeks of additional treatment for migraine under the care of that primary care provider.

Participants

Study participants included both primary care providers and their patients. Eligible health care providers included physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants responsible for performing headache assessments in US primary care practices that did not routinely use a questionnaire to screen headache patients prior to the study.

Eligible patients for Phase 1 were the first 100 consecutive 18- to 65-year-old patients in each practice who agreed to complete the Headache Assessment Quiz. Patients were eligible for Phase 1 regardless of whether they were consulting for headache. Patients from Phase 1 were eligible for Phase 2 if they screened positive for migraine on the Headache Assessment Quiz, had a confirmed clinical diagnosis of migraine meeting IHS criteria 1.1 or 1.2,19 and were willing to remain under the care of the study investigator and to treat headaches with therapy recommended by that investigator for 12 weeks.

Procedures

Phase 1

Primary care providers completed an Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education-accredited educational program consisting of a 38-minute DVD on migraine diagnosis and screening. After they completed the educational program, health care providers administered the Headache Assessment Quiz and HIT-6 to a target of 100 consecutively consulting patients regardless of patients’ reason for consulting. For patients who screened positive for migraine on the Headache Assessment Quiz, primary care providers recorded whether or not in their clinical judgment they confirmed a diagnosis of migraine by IHS criteria19 and whether or not patients reported, in response to a question, that they had received a migraine diagnosis from a health care professional before the study.

Phase 2

Primary care providers were asked to recruit up to 10 Phase-1 patients with a confirmed clinical diagnosis of migraine for Phase 2 of the study. At least half of the patients recruited in each practice were to have received their first clinical diagnosis of migraine during the study. All patients provided written, informed consent to participate in Phase 2.

At the beginning of Phase 2, eligible patients received Migraine Care Program educational materials including a migraine diary and a pamphlet about the causes, triggers, symptoms of migraine, and migraine types. They received migraine care for the ensuing 12 weeks under the supervision of the investigator. Investigators could prescribe any pharmacological or nonpharmacological migraine treatment to patients at their discretion.

Measures

In questionnaires administered at the beginning of the study before they initiated the Migraine Care Program (baseline) and again at the end of Phase 2, primary care providers rated the difficulty of assessing and treating patients with headache (0 = not at all difficult; 10 = extremely difficult), the importance of understanding the impact of headaches on a patient’s life when making treatment decisions (on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from very important to very unimportant), and their satisfaction (on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from very satisfied to very dissatisfied) with how well patients describe their headache severity and how well patients describe the physical, emotional, and financial impact of headaches.

For the questions on patient communication about headaches, providers were instructed to respond with respect to their general experience with patients for the baseline questionnaire and with respect to their experience with patients in Phase 2 of the study for the end-of-study questionnaire. The end-of-study questionnaire also contained items on which primary care providers rated satisfaction with the use of the Headache Assessment Quiz to facilitate (a) understanding of the impact of headaches on patients’ lives; (b) treatment decisions; and (c) identification of headache patients requiring better treatment and indicated whether or not they would recommend the Headache Assessment Quiz for use in clinical practice.

In questionnaires administered at the beginning of Phase 2 and again at the end of the study, patients who participated in Phase 2 rated their satisfaction (on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from very satisfied to very dissatisfied) with the medication used to treat migraine headaches and with the quality of medical care received for migraine. In addition, patients rated the bothersomeness of side effects of medication used to treat migraine headaches (on a 5-point categorical scale ranging from not at all to extremely). At the beginning of Phase 2, patients listed the medications they had used during the 3 months before the study to treat headaches. HIT-6, which was first administered at study entry, was also administered at the end of Phase 2.

Responses to the primary care provider and patient questionnaires were summarized with descriptive statistics. The Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test was used to compare differences between baseline and the end of the study in the distribution of percentages of respondents to each question on satisfaction, bothersomeness, and importance; in median primary care provider ratings of difficulty of assessing and treating headache patients; and in distribution of HIT-6 scores (<50 = little to no impact of headache; 50–55 = some impact; 56–59 = substantial impact; ≥60 = severe impact).

In a subgroup analysis, baseline characteristics and end-of-study assessments were summarized separately for Phase 2 patients who reported a pre-study diagnosis of migraine and those who reported no pre-study diagnosis of migraine. Differences between subgroups were compared with chi-square tests as appropriate.

Results

Phase 1 participants

Forty-nine primary care providers (physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) participated in the Migraine Care Program (TABLE 1). Providers’ mean age was 44 years (SD=8.28). The majority (86%) were in group practice. The number of patients recruited to complete the Headache Assessment Quiz during Phase 1 of the study was 4443.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of study participants

| PRIMARY CARE PROVIDERS | |

| N | 49 |

| Type of provider, % | |

| Physician | 84 |

| Nurse practitioner | 100 |

| Physician assistant | 6 |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 44 (8.3) |

| Female, % | 33 |

| Practice type, % | |

| Group | 86 |

| Private | 14 |

| PATIENTS: PHASE 2 | |

| N | 470 |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 41 (11.9) |

| Female, % | 77 |

| Race, % | |

| White | 85 |

| Black | 6 |

| Hispanic | 6 |

| Other | 2† |

| Medications used for headache during the 3 months before the study,* % | |

| Over-the-counter medications | 70 |

| Triptans | 19 |

| Prescription NSAIDs | 14 |

| Combination analgesic | 9 |

| Narcotics | 5 |

| *Patients could list more than one medication. | |

| †Does not add to 100% because patients could have taken multiple medications. | |

Migraine diagnosis during Phase 1

Of the 4443 patients who completed the Headache Assessment Quiz in Phase 1, 1527 (34%) screened positive for migraine. Of these 1527 patients who screened positive for migraine, 1126 (74% of the 1527 patients screening positive for migraine) had their diagnosis confirmed during further evaluation by their primary care provider (FIGURE 3). More than half (52%) of the 1126 patients with a confirmed migraine diagnosis reported that they had not received a health care professional’s diagnosis of migraine prior to the study.

The proportion of patients with migraine as confirmed by a clinical migraine diagnosis was 25% (1126/4443) in the sample as a whole, which included all patients who had consulted these primary care practices for any reason and who had agreed to complete the Headache Assessment Quiz.

FIGURE 3

Prevalence of migraine among patients who consulted primary care providers for any reason and who agreed to complete the Headache Assessment Quiz

PCP’s perceptions of headache management before and after participation in the program

Primary care providers’ participation in the Migraine Care Program was associated with an increase in awareness of headache impact. At the end of Phase 2 compared with the beginning of the study, significantly more providers rated understanding headache impact as being important or very important in treatment decisions (87% vs 74%; P<.05) (TABLE 2).

Primary care providers’ participation in the Migraine Care Program was also associated with a perceived reduction in the challenges of providing headache care. At the end of Phase 2 compared with the beginning of the study, primary care providers reported assessing and treating headache to be significantly less difficult (median score = 6 at baseline and 3 at the end of the study; P<.001) (TABLE 2).

This improvement was accompanied by the perception of better patient communication about headaches: the proportions of primary care providers indicating that they were satisfied or very satisfied with patients’ descriptions of headache severity/symptoms and headache impact were significantly higher for patients they treated in Phase 2 than for headache patients they had treated prior to the study (76% vs 20% for severity/symptoms; 67% vs 27% for headache impact; P<.001 for both comparisons) (FIGURE 4).

The majority of providers indicated that they were satisfied or very satisfied with the use of the Headache Assessment Quiz as a tool for each of the dimensions assessed: understanding headache severity (88%), understanding headache impact (78%), making treatment decisions (71%), and identifying patients requiring treatment (86%) (FIGURE 4). Nearly all providers (96%) indicated that they would recommend the Headache Assessment Quiz for use in clinical practice (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Primary care providers’ perceptions of headache management at baseline and at the end of the study after participating in the Migraine Care Program

| BASELINE | END OF STUDY | |

| Knowledge of headache impact is important/very important in making decisions about treatment, % | 74 | 87* |

| Difficulty in headache assessment, median score† (range) | 6 (2–8) | 3‡ (1–7) |

| Would recommend the Headache Assessment Quiz for use in clinical practice, % | NA | 96 |

| *P<.05 vs baseline. | ||

| †Difficulty was scored on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all difficult) to 10 (extremely difficult). | ||

| ‡P<.001 vs baseline. | ||

FIGURE 4

Percentages of primary care providers who were satisfied/very satisfied with patient communication and the use of the Headache Assessment Quiz

Patients’ perceptions of headache care by PCPs participating in the Migraine Care Program

Phase 2 sample. The number of patients who participated in Phase 2 was 470 (TABLE 1). Mean age of patients in the Phase 2 sample was 41 years (SD=11.9). The majority of patients were white (85%) and were women (77%).

Medications

Among the 470 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of migraine who participated in Phase 2, the most common medications used to treat headaches during the 3 months prior to the study were over-the-counter medications (70% of patients) (TABLE 1). Fewer than one in five patients (19%) reported treating their pre-study headaches with migraine-specific triptan therapy.

At the beginning of Phase 2, primary care providers changed the headache medication regimen of 197 of these patients (42%). Of the 205 total changes to medication regimens, 72% involved adding a triptan; 10% involved adding other medications; 11% involved discontinuation of a medication; and 7% involved dose adjustment.

The changes to medication regimens were associated with significant improvement in satisfaction with medication in the subset of patients who finished Phase 2 and completed the end-of-study questionnaire (n=258). More patients indicated that they were satisfied or very satisfied with the effectiveness of headache medications used during the study than with headache medications used before the study (42% versus 26%; P<.005) (FIGURE 5). In addition, with respect to overall satisfaction with medication, more patients reported themselves to be satisfied or very satisfied with the medications used during the study than with those used before the study (41% vs 29%; P<.005) (FIGURE 5). Bothersomeness of side effects of migraine medication did not differ during the study versus before the study. Most patients (63%) reported themselves to be not at all bothered by medication side effects both during the study and before the study.

FIGURE 5

Percentage of patients who were satisfied/very satisfied with medication and migraine care

Quality of care

The proportion of patients indicating that they were satisfied or very satisfied with the overall quality of migraine care was significantly higher for care received during the study than care received before the study (48% vs 32%; P<.001) (FIGURE 5).

Impact of headache

Patients’ HIT-6 scores reflected significantly less impact of headache at the end of Phase 2 compared with the beginning of the study. The percentage of patients whose headaches impacted their lives substantially or very severely was 75.3% at enrollment compared with 68.8% at the end of the study (P<.05).

Patients with pre-study migraine diagnosis vs those without

Of the 470 patients in the Phase 2 sample, 230 reported a pre-study diagnosis of migraine and 240 report no pre-study diagnosis of migraine. Patients who reported a pre-study migraine diagnosis compared with those who did not appeared to have more severe migraine at baseline as reflected by a higher frequency of severe pain, a longer duration of typical migraine attacks, and higher frequency of HIT-6 scores reflecting substantial or very severe impact of headaches (TABLE 3).

Patients with no prior diagnosis were significantly less satisfied with care and medication at baseline than patients with a prior diagnosis. While satisfaction increased and headache impact decreased from baseline to the end of Phase 2 both in patients who reported a prior diagnosis and those who did not, improvement was greater in those without a prior diagnosis (TABLE 3).

Acknowledgments

Some of the data described in this manuscript were presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the American Headache Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. The study described in this manuscript was funded by GlaxoSmithKline. The authors acknowledge Jane Saiers, PhD, for assistance with writing the manuscript. Dr. Saiers’ work on the manuscript was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

CORRESPONDENCE

Stephen Landy, MD, Wesley Headache Clinic, 8974 Bridge Forest Drive, Memphis, TN 38138. E-mail: [email protected]

- Consider using the Headache Assessment Quiz, which 76% of providers in this study said enabled patients to adequately convey headache severity/symptoms, compared with just 20% of providers at baseline who thought patients communicated clearly.

- Use the quiz also to better understand the impact of migraine on a patient’s life, and to help determine which patients need migraine-specific therapy.

Up to 25% of patients in a typical primary care practice could be afflicted with migraine, and many of them simply do not report their headaches. Their silence does not necessarily imply adequate control with self-medication. Other concerns may command their attention, or inadequate communication may mask the issue. Whatever the reason, too few of them receive migraine-specific medications and proper instruction on avoiding headache triggers that could relieve the well-known burden of this disorder. Our study verifies the success of a program for screening—including a Headache Assessment Quiz—and treating migraine that also eases the burden of management for you.

For more original research on the treatment of migraines, see “Do family physicians fail to provide triptans for patients with migraine?”

We begin with a summary of our findings, and then give a detailed account of our study methods and results.

How many patients are slipping through the cracks?

Nearly half of all persons with migraine in the United States have not received a diagnosis for their disorder.1 Many of them suffer substantial functional impairment in daily activities and, thus, a diminished quality of life.

What’s to blame for this underdiagnosis? Perhaps a person’s failure to consult a physician for headache, poor patient-physician communication, comorbid conditions that obscure the presence or significance of headache, or a lack of time and resources devoted to detecting and managing migraine in the health care setting.2-5 In 2 recent studies conducted mainly in primary care settings, the frequency of unrecognized migraine among patients consulting for headache ranged from 48% to 60%.6,7

Even when migraine is recognized, quality of care is often suboptimal. In 1999, only 4 of 10 US migraineurs used prescription medication for migraine.6 In a recently published study that used 2002–2003 retrospective data from more than 30 managed care organizations, 50% of patients with a migraine diagnosis who had prescription drug coverage filled a prescription for a medication commonly used to treat migraine.8

We need a reliable system for migraine detection and management.

Migraine Care Program proves its worth

The Migraine Care Program (at www.migrainecareprogram.com) is a disease-management program employing educational materials and clinical assessment tools to help health care providers and patients improve awareness and recognition of migraine and the quality of care received by migraine sufferers. Components of the program:

- Informational modules on migraine epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, triggers, impact, and treatment

- Headache diary for patients

- Action plan for patients to complete with their health care providers

- Information for patients on effectively communicating with their health care providers about headache

- 10-question Headache Assessment Quiz and its supplement, which screen for the presence of migraine (FIGURE 1)

- 6-item Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) (FIGURE 2), a reliable, valid measure of the impact of headache on patients’ lives.9

This article reports the results of a prospective, two-phase study undertaken to assess (Phase 1) the utility of the Headache Assessment Quiz in facilitating recognition of migraine; and (Phase 2) the usefulness of the Migraine Care Program from the perspectives of both primary care providers and their patients. The study is unique in being one of a few to assess the effectiveness of a disease management program in improving patient outcomes or influencing physician’s behavior.

FIGURE 1

Headache Assessment Quiz

FIGURE 2

Headache Impact Test: HIT-6 (version 1.0)

How we measured success

In our study, primary care providers using the Migraine Care Program’s Headache Assessment Quiz as a screening tool diagnosed migraine in 25% of 4443 patients. That 1 in 4 patients consulting these primary care clinics for any reason had migraine is consistent with the estimated prevalence of migraine in the general population.1 More than half (52%) of those given a clinical diagnosis of migraine in this study had not previously received the diagnosis, which is also consistent with previous figures on unrecognized migraine.1,6,7 This pattern of results suggests that provider education and use of the Headache Assessment Quiz facilitated recognition of migraine in this sample.

Providers said the Headache Assessment Quiz improved management decisions. Three of 4 (74%) patients who tested positive for migraine on the Headache Assessment Quiz were subsequently given a clinical diagnosis of migraine after further evaluation by the primary care provider. Providers’ ratings of the Headache Assessment Quiz indicate the tool proved useful in multiple aspects of migraine care: understanding headache severity and impact, facilitating treatment decisions, and identifying patients requiring treatment. By the end of the study, providers found headache patients less difficult to assess and manage than before.

Clear benefits to patients. For 42% of patients with migraine, providers adjusted the pre-study medication regimens—most often by adding a migraine-specific triptan. On post-study surveys, significantly more patients said they were satisfied or very satisfied with the effectiveness of medication and with the overall quality of migraine care compared with the beginning of the study. The impact of headache on patients’ lives as determined from HIT-6 scores was less at the end of the study compared with the beginning.

A subgroup analysis among Phase 2 patients confirmed the value of the program. Phase 2 patients reporting no pre-study diagnosis of migraine were significantly less satisfied with care and medication at baseline than patients reporting a pre-study migraine diagnosis—even though patients reporting no pre-study diagnosis had less severe migraine at baseline. Patients with previously unrecognized migraine responded well to care in our study. Though satisfaction increased and headache impact decreased from baseline to the end of Phase 2 for both sets of patients, improvement was greater for those without a prior diagnosis.

Migraine affects 18% of women and 7% of men in the United States.1 A large body of research conducted over the past decade contradicts the historical conception of migraine as a trivial illness and has established it as a disabling condition warranting aggressive management.10-13 Concurrently, understanding of the pathophysiology of migraine has evolved; and new, migraine-specific treatments that can relieve pain and restore patients’ functional ability have been introduced.14,15 Despite these advances, several barriers to optimizing migraine care remain. Perhaps the most significant obstacle to effective migraine care, failure to recognize and diagnose migraine occurs alarmingly often.2,6,7,16,17 In a 1999 US population-based survey, less than half (48%) of those meeting International Headache Society (IHS) diagnostic criteria for migraine reported having received a physician diagnosis of migraine.1 Frequency of physician diagnosis of migraine in 1999 did not increase appreciably from diagnosis rates in 1989 although consultations for headache tripled over the 10-year period. Underrecognition and suboptimal management of migraine may be particularly problematic in the primary care setting, where the majority of migraine sufferers consult.

The suboptimal nature of migraine care is also reflected in patients’ assessments of medical care. In a recent study of patients with primary headache diagnoses in three geographically diverse primary care institutions in the United States, 1 of 4 patients with severe headaches reported dissatisfaction with their headache care; and 3 of 4 reported moderate or severe problems with headache management.18

Limitations of the study. First, patients were enrolled only if they agreed to complete the Headache Assessment Quiz. Thus, regarding characteristics relevant to study assessments, selection bias may have occurred if patients who agreed to take the quiz differed systematically from those who did not.

Second, attrition during Phase 2—though relatively low for a naturalistic study that, unlike a clinical trial, did not use incentives such as provision of study medication—might have biased the results of patient assessments at the end of the study. Attrition could have inflated the patient-satisfaction and other end-of-study ratings of medication and migraine care if dissatisfied patients were more likely to withdraw prematurely from the study than were satisfied patients.

Third, the study lacked a control group because of the difficulty in blinding investigators in a naturalistic study.

Strengths of the study. Among several disease management programs for migraine, the Migraine Care Program is unique in being one of the few whose effects on migraine care have been assessed. In this study, application of the Migraine Care Program was evaluated in the “real-world” clinical setting and as used by providers (physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants) typically responsible for headache care in primary care centers across the US. These characteristics enhance the probability that the results reflect those achievable in actual clinical practice. The comprehensive nature of the study assessments, which involved both primary care providers and patients, supports the benefits of the program.

Methods

This prospective, observational study had 2 phases. During Phase 1, primary care providers were introduced to the Migraine Care Program, and they administered the Headache Assessment Quiz to consulting patients who agreed to complete it. During Phase 2, a subset of patients who screened positive for migraine on the Headache Assessment Quiz in Phase 1 and whose migraine diagnosis was confirmed by their primary care provider received 12 weeks of additional treatment for migraine under the care of that primary care provider.

Participants

Study participants included both primary care providers and their patients. Eligible health care providers included physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants responsible for performing headache assessments in US primary care practices that did not routinely use a questionnaire to screen headache patients prior to the study.

Eligible patients for Phase 1 were the first 100 consecutive 18- to 65-year-old patients in each practice who agreed to complete the Headache Assessment Quiz. Patients were eligible for Phase 1 regardless of whether they were consulting for headache. Patients from Phase 1 were eligible for Phase 2 if they screened positive for migraine on the Headache Assessment Quiz, had a confirmed clinical diagnosis of migraine meeting IHS criteria 1.1 or 1.2,19 and were willing to remain under the care of the study investigator and to treat headaches with therapy recommended by that investigator for 12 weeks.

Procedures

Phase 1

Primary care providers completed an Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education-accredited educational program consisting of a 38-minute DVD on migraine diagnosis and screening. After they completed the educational program, health care providers administered the Headache Assessment Quiz and HIT-6 to a target of 100 consecutively consulting patients regardless of patients’ reason for consulting. For patients who screened positive for migraine on the Headache Assessment Quiz, primary care providers recorded whether or not in their clinical judgment they confirmed a diagnosis of migraine by IHS criteria19 and whether or not patients reported, in response to a question, that they had received a migraine diagnosis from a health care professional before the study.

Phase 2

Primary care providers were asked to recruit up to 10 Phase-1 patients with a confirmed clinical diagnosis of migraine for Phase 2 of the study. At least half of the patients recruited in each practice were to have received their first clinical diagnosis of migraine during the study. All patients provided written, informed consent to participate in Phase 2.

At the beginning of Phase 2, eligible patients received Migraine Care Program educational materials including a migraine diary and a pamphlet about the causes, triggers, symptoms of migraine, and migraine types. They received migraine care for the ensuing 12 weeks under the supervision of the investigator. Investigators could prescribe any pharmacological or nonpharmacological migraine treatment to patients at their discretion.

Measures

In questionnaires administered at the beginning of the study before they initiated the Migraine Care Program (baseline) and again at the end of Phase 2, primary care providers rated the difficulty of assessing and treating patients with headache (0 = not at all difficult; 10 = extremely difficult), the importance of understanding the impact of headaches on a patient’s life when making treatment decisions (on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from very important to very unimportant), and their satisfaction (on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from very satisfied to very dissatisfied) with how well patients describe their headache severity and how well patients describe the physical, emotional, and financial impact of headaches.

For the questions on patient communication about headaches, providers were instructed to respond with respect to their general experience with patients for the baseline questionnaire and with respect to their experience with patients in Phase 2 of the study for the end-of-study questionnaire. The end-of-study questionnaire also contained items on which primary care providers rated satisfaction with the use of the Headache Assessment Quiz to facilitate (a) understanding of the impact of headaches on patients’ lives; (b) treatment decisions; and (c) identification of headache patients requiring better treatment and indicated whether or not they would recommend the Headache Assessment Quiz for use in clinical practice.

In questionnaires administered at the beginning of Phase 2 and again at the end of the study, patients who participated in Phase 2 rated their satisfaction (on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from very satisfied to very dissatisfied) with the medication used to treat migraine headaches and with the quality of medical care received for migraine. In addition, patients rated the bothersomeness of side effects of medication used to treat migraine headaches (on a 5-point categorical scale ranging from not at all to extremely). At the beginning of Phase 2, patients listed the medications they had used during the 3 months before the study to treat headaches. HIT-6, which was first administered at study entry, was also administered at the end of Phase 2.

Responses to the primary care provider and patient questionnaires were summarized with descriptive statistics. The Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test was used to compare differences between baseline and the end of the study in the distribution of percentages of respondents to each question on satisfaction, bothersomeness, and importance; in median primary care provider ratings of difficulty of assessing and treating headache patients; and in distribution of HIT-6 scores (<50 = little to no impact of headache; 50–55 = some impact; 56–59 = substantial impact; ≥60 = severe impact).

In a subgroup analysis, baseline characteristics and end-of-study assessments were summarized separately for Phase 2 patients who reported a pre-study diagnosis of migraine and those who reported no pre-study diagnosis of migraine. Differences between subgroups were compared with chi-square tests as appropriate.

Results

Phase 1 participants

Forty-nine primary care providers (physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) participated in the Migraine Care Program (TABLE 1). Providers’ mean age was 44 years (SD=8.28). The majority (86%) were in group practice. The number of patients recruited to complete the Headache Assessment Quiz during Phase 1 of the study was 4443.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of study participants

| PRIMARY CARE PROVIDERS | |

| N | 49 |

| Type of provider, % | |

| Physician | 84 |

| Nurse practitioner | 100 |

| Physician assistant | 6 |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 44 (8.3) |

| Female, % | 33 |

| Practice type, % | |

| Group | 86 |

| Private | 14 |

| PATIENTS: PHASE 2 | |

| N | 470 |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 41 (11.9) |

| Female, % | 77 |

| Race, % | |

| White | 85 |

| Black | 6 |

| Hispanic | 6 |

| Other | 2† |

| Medications used for headache during the 3 months before the study,* % | |

| Over-the-counter medications | 70 |

| Triptans | 19 |

| Prescription NSAIDs | 14 |

| Combination analgesic | 9 |

| Narcotics | 5 |

| *Patients could list more than one medication. | |

| †Does not add to 100% because patients could have taken multiple medications. | |

Migraine diagnosis during Phase 1

Of the 4443 patients who completed the Headache Assessment Quiz in Phase 1, 1527 (34%) screened positive for migraine. Of these 1527 patients who screened positive for migraine, 1126 (74% of the 1527 patients screening positive for migraine) had their diagnosis confirmed during further evaluation by their primary care provider (FIGURE 3). More than half (52%) of the 1126 patients with a confirmed migraine diagnosis reported that they had not received a health care professional’s diagnosis of migraine prior to the study.

The proportion of patients with migraine as confirmed by a clinical migraine diagnosis was 25% (1126/4443) in the sample as a whole, which included all patients who had consulted these primary care practices for any reason and who had agreed to complete the Headache Assessment Quiz.

FIGURE 3

Prevalence of migraine among patients who consulted primary care providers for any reason and who agreed to complete the Headache Assessment Quiz

PCP’s perceptions of headache management before and after participation in the program

Primary care providers’ participation in the Migraine Care Program was associated with an increase in awareness of headache impact. At the end of Phase 2 compared with the beginning of the study, significantly more providers rated understanding headache impact as being important or very important in treatment decisions (87% vs 74%; P<.05) (TABLE 2).

Primary care providers’ participation in the Migraine Care Program was also associated with a perceived reduction in the challenges of providing headache care. At the end of Phase 2 compared with the beginning of the study, primary care providers reported assessing and treating headache to be significantly less difficult (median score = 6 at baseline and 3 at the end of the study; P<.001) (TABLE 2).

This improvement was accompanied by the perception of better patient communication about headaches: the proportions of primary care providers indicating that they were satisfied or very satisfied with patients’ descriptions of headache severity/symptoms and headache impact were significantly higher for patients they treated in Phase 2 than for headache patients they had treated prior to the study (76% vs 20% for severity/symptoms; 67% vs 27% for headache impact; P<.001 for both comparisons) (FIGURE 4).

The majority of providers indicated that they were satisfied or very satisfied with the use of the Headache Assessment Quiz as a tool for each of the dimensions assessed: understanding headache severity (88%), understanding headache impact (78%), making treatment decisions (71%), and identifying patients requiring treatment (86%) (FIGURE 4). Nearly all providers (96%) indicated that they would recommend the Headache Assessment Quiz for use in clinical practice (TABLE 2).

TABLE 2

Primary care providers’ perceptions of headache management at baseline and at the end of the study after participating in the Migraine Care Program

| BASELINE | END OF STUDY | |

| Knowledge of headache impact is important/very important in making decisions about treatment, % | 74 | 87* |

| Difficulty in headache assessment, median score† (range) | 6 (2–8) | 3‡ (1–7) |

| Would recommend the Headache Assessment Quiz for use in clinical practice, % | NA | 96 |

| *P<.05 vs baseline. | ||

| †Difficulty was scored on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all difficult) to 10 (extremely difficult). | ||

| ‡P<.001 vs baseline. | ||

FIGURE 4

Percentages of primary care providers who were satisfied/very satisfied with patient communication and the use of the Headache Assessment Quiz

Patients’ perceptions of headache care by PCPs participating in the Migraine Care Program

Phase 2 sample. The number of patients who participated in Phase 2 was 470 (TABLE 1). Mean age of patients in the Phase 2 sample was 41 years (SD=11.9). The majority of patients were white (85%) and were women (77%).

Medications

Among the 470 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of migraine who participated in Phase 2, the most common medications used to treat headaches during the 3 months prior to the study were over-the-counter medications (70% of patients) (TABLE 1). Fewer than one in five patients (19%) reported treating their pre-study headaches with migraine-specific triptan therapy.

At the beginning of Phase 2, primary care providers changed the headache medication regimen of 197 of these patients (42%). Of the 205 total changes to medication regimens, 72% involved adding a triptan; 10% involved adding other medications; 11% involved discontinuation of a medication; and 7% involved dose adjustment.

The changes to medication regimens were associated with significant improvement in satisfaction with medication in the subset of patients who finished Phase 2 and completed the end-of-study questionnaire (n=258). More patients indicated that they were satisfied or very satisfied with the effectiveness of headache medications used during the study than with headache medications used before the study (42% versus 26%; P<.005) (FIGURE 5). In addition, with respect to overall satisfaction with medication, more patients reported themselves to be satisfied or very satisfied with the medications used during the study than with those used before the study (41% vs 29%; P<.005) (FIGURE 5). Bothersomeness of side effects of migraine medication did not differ during the study versus before the study. Most patients (63%) reported themselves to be not at all bothered by medication side effects both during the study and before the study.

FIGURE 5

Percentage of patients who were satisfied/very satisfied with medication and migraine care

Quality of care

The proportion of patients indicating that they were satisfied or very satisfied with the overall quality of migraine care was significantly higher for care received during the study than care received before the study (48% vs 32%; P<.001) (FIGURE 5).

Impact of headache

Patients’ HIT-6 scores reflected significantly less impact of headache at the end of Phase 2 compared with the beginning of the study. The percentage of patients whose headaches impacted their lives substantially or very severely was 75.3% at enrollment compared with 68.8% at the end of the study (P<.05).

Patients with pre-study migraine diagnosis vs those without

Of the 470 patients in the Phase 2 sample, 230 reported a pre-study diagnosis of migraine and 240 report no pre-study diagnosis of migraine. Patients who reported a pre-study migraine diagnosis compared with those who did not appeared to have more severe migraine at baseline as reflected by a higher frequency of severe pain, a longer duration of typical migraine attacks, and higher frequency of HIT-6 scores reflecting substantial or very severe impact of headaches (TABLE 3).

Patients with no prior diagnosis were significantly less satisfied with care and medication at baseline than patients with a prior diagnosis. While satisfaction increased and headache impact decreased from baseline to the end of Phase 2 both in patients who reported a prior diagnosis and those who did not, improvement was greater in those without a prior diagnosis (TABLE 3).

Acknowledgments

Some of the data described in this manuscript were presented at the 47th Annual Meeting of the American Headache Society, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. The study described in this manuscript was funded by GlaxoSmithKline. The authors acknowledge Jane Saiers, PhD, for assistance with writing the manuscript. Dr. Saiers’ work on the manuscript was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

CORRESPONDENCE

Stephen Landy, MD, Wesley Headache Clinic, 8974 Bridge Forest Drive, Memphis, TN 38138. E-mail: [email protected]