User login

Much has been written about “the difficult patient” in the medical literature.1,2 Also labeled as a “heartsink patient,” “hateful patient,” and “black hole,” they possess characteristics that evoke powerful, often negative, emotional responses in providers that can be counter-therapeutic. “The difficult provider” also is thought to contribute to the failure of the patient encounter,3 and providers may have limited awareness of these patient–provider characteristics that can lead to such interactions. Early identification of these characteristics is essential to implementing effective interventions for the care of a difficult patient.

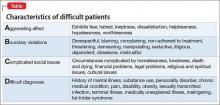

The mnemonic ABCD highlights patient characteristics that suggest you are dealing with a difficult patient (Table).

7 Negatives that affect the provider–patient relationship

The 7 Es highlight negative provider-related variables that contribute to perceived and actual difficulty providing care. As a psychiatrist doing consultation-liaison work, this memory device also can be a tool to educate physician–colleagues, nursing staff, and other members of the treatment team.

Expertise. Lack of basic knowledge or experience with your patient’s condition and circumstances, or not being familiar with available resources, could limit your confidence, be counter-productive, and lead to inappropriate care.

Experiences. Current and past life experiences could negatively color a provider’s feelings, thoughts, and interactions with the patient. Negative interpersonal experiences could manifest as countertransference.

Empathy. The inability to empathize makes it difficult to understand the patient, creating distance between you and the patient.

Engagement level. A lack of rapport and ineffective communication leads to a patient feeling misunderstood and unsatisfied with the clinical interaction.

Emotions. Feeling tired, angry, or resentful harms the provider–patient interaction.

Environment. A stressful, loud, pressured environment filled with distractions can undermine the provider–patient relationship.

Extra help. Limited access to, and the unavailability of, social services, housing, and similar resources could make an already difficult situation seem impossible to solve. Working without such help can lead to feelings of helplessness and hopelessness for you and your patient.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. The views expressed in this publication/presentation are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

1. Strous RD, Ulman A, Kotler M. The hateful patient revisited: relevance for 21st century medicine. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17(6):387-393.

2. Smith S. Dealing with the difficult patient. Postgrad Med J. 1995;71(841):653-657.

3. Hawken SJ. Strategies for dealing with the challenging patient. N Z Fam Physician. 2005;32(4):266-269.

Much has been written about “the difficult patient” in the medical literature.1,2 Also labeled as a “heartsink patient,” “hateful patient,” and “black hole,” they possess characteristics that evoke powerful, often negative, emotional responses in providers that can be counter-therapeutic. “The difficult provider” also is thought to contribute to the failure of the patient encounter,3 and providers may have limited awareness of these patient–provider characteristics that can lead to such interactions. Early identification of these characteristics is essential to implementing effective interventions for the care of a difficult patient.

The mnemonic ABCD highlights patient characteristics that suggest you are dealing with a difficult patient (Table).

7 Negatives that affect the provider–patient relationship

The 7 Es highlight negative provider-related variables that contribute to perceived and actual difficulty providing care. As a psychiatrist doing consultation-liaison work, this memory device also can be a tool to educate physician–colleagues, nursing staff, and other members of the treatment team.

Expertise. Lack of basic knowledge or experience with your patient’s condition and circumstances, or not being familiar with available resources, could limit your confidence, be counter-productive, and lead to inappropriate care.

Experiences. Current and past life experiences could negatively color a provider’s feelings, thoughts, and interactions with the patient. Negative interpersonal experiences could manifest as countertransference.

Empathy. The inability to empathize makes it difficult to understand the patient, creating distance between you and the patient.

Engagement level. A lack of rapport and ineffective communication leads to a patient feeling misunderstood and unsatisfied with the clinical interaction.

Emotions. Feeling tired, angry, or resentful harms the provider–patient interaction.

Environment. A stressful, loud, pressured environment filled with distractions can undermine the provider–patient relationship.

Extra help. Limited access to, and the unavailability of, social services, housing, and similar resources could make an already difficult situation seem impossible to solve. Working without such help can lead to feelings of helplessness and hopelessness for you and your patient.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. The views expressed in this publication/presentation are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Much has been written about “the difficult patient” in the medical literature.1,2 Also labeled as a “heartsink patient,” “hateful patient,” and “black hole,” they possess characteristics that evoke powerful, often negative, emotional responses in providers that can be counter-therapeutic. “The difficult provider” also is thought to contribute to the failure of the patient encounter,3 and providers may have limited awareness of these patient–provider characteristics that can lead to such interactions. Early identification of these characteristics is essential to implementing effective interventions for the care of a difficult patient.

The mnemonic ABCD highlights patient characteristics that suggest you are dealing with a difficult patient (Table).

7 Negatives that affect the provider–patient relationship

The 7 Es highlight negative provider-related variables that contribute to perceived and actual difficulty providing care. As a psychiatrist doing consultation-liaison work, this memory device also can be a tool to educate physician–colleagues, nursing staff, and other members of the treatment team.

Expertise. Lack of basic knowledge or experience with your patient’s condition and circumstances, or not being familiar with available resources, could limit your confidence, be counter-productive, and lead to inappropriate care.

Experiences. Current and past life experiences could negatively color a provider’s feelings, thoughts, and interactions with the patient. Negative interpersonal experiences could manifest as countertransference.

Empathy. The inability to empathize makes it difficult to understand the patient, creating distance between you and the patient.

Engagement level. A lack of rapport and ineffective communication leads to a patient feeling misunderstood and unsatisfied with the clinical interaction.

Emotions. Feeling tired, angry, or resentful harms the provider–patient interaction.

Environment. A stressful, loud, pressured environment filled with distractions can undermine the provider–patient relationship.

Extra help. Limited access to, and the unavailability of, social services, housing, and similar resources could make an already difficult situation seem impossible to solve. Working without such help can lead to feelings of helplessness and hopelessness for you and your patient.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. The views expressed in this publication/presentation are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

1. Strous RD, Ulman A, Kotler M. The hateful patient revisited: relevance for 21st century medicine. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17(6):387-393.

2. Smith S. Dealing with the difficult patient. Postgrad Med J. 1995;71(841):653-657.

3. Hawken SJ. Strategies for dealing with the challenging patient. N Z Fam Physician. 2005;32(4):266-269.

1. Strous RD, Ulman A, Kotler M. The hateful patient revisited: relevance for 21st century medicine. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17(6):387-393.

2. Smith S. Dealing with the difficult patient. Postgrad Med J. 1995;71(841):653-657.

3. Hawken SJ. Strategies for dealing with the challenging patient. N Z Fam Physician. 2005;32(4):266-269.