User login

MODULE 1: Historical Review of Evidence-Based Treatment of Hypertension

MODULE 3: Using Thiazide-Type Diuretics in African Americans with Hypertension

Dr White is President of the American Society of Hypertension (voluntary unpaid position) and is a paid cardiovascular safety consultant to Abbott Immunology; Ardea Biosciences, Inc; AstraZeneca; BioSante Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Forest Research Institute, Inc; Novartis Corporation; Roche Laboratories, Inc; and Takeda Global Research & Development Center, Inc. He holds no stocks in pharmaceutical companies and is not a member of any speakers’ bureaus.

Introduction

Hypertension is a transformative condition in modern medicine due to the various numeric definitions of the disease, the decision of when to initiate therapy and to what level to treat, and the evolution of our understanding of the long-term complications of the hypertensive disease process. Hypertension is notable as 1 of the first conditions that only rarely manifested symptoms and whose eventual sequelae could take years, if not decades, to become known. In addition, hypertension was the first condition in which clinicians initiated therapy for patients who were otherwise healthy. Hypertension also led to 1 of the first screening programs for any disease as well as the first robust preventive effort for a chronic medical condition.1

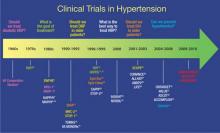

Clinical trials have been performed for 5 decades to evaluate the potential benefits of lowering blood pressure (BP) in patients with hypertension and its comorbid conditions (FIGURE 1).2-37 The first clinical trial to identify the increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) mortality related to hypertension was published in the mid-1960s.2,38 In fact, the Veterans Administration (VA) Cooperative trial was the first randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multi-institutional drug efficacy trial ever conducted in CV medicine.38 It involved 143 men who met the 1964 definition of hypertension (ie, diastolic BP [DBP] ≥115 mm Hg) and who were randomized to either triple therapy with low doses of hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), reserpine, and hydralazine, or to placebo. The trial was terminated early when, after 18 months of treatment, rates of morbidity and mortality were substantially lower in the treated group than in the placebo group.2 The trial was the first to confirm that antihypertensive treatment, even in patients with existing CV damage and significant hypertension, could dramatically reduce the incidence of stroke, congestive heart failure (CHF), and progressive kidney damage.38

FIGURE 1

Clinical trials in hypertension during the past 5 decades

ACCOMPLISH, Avoiding Cardiovascular Events Through Combination Therapy in Patients Living With Systolic Hypertension trial; ALLHAT, Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial; ALTITUDE, Aliskiren Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Using Cardiovascular and Renal Disease Endpoints; ANBP1, Australian National Blood Pressure Study 1; ANBP2, Australian National Blood Pressure Study 2; ASCOT, Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial; ATMOSPHERE, Efficacy and Safety of Aliskiren and Aliskiren/Enalapril Combination on Morbi-mortality in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure study; CAPPP, Captopril Prevention Project; CONVINCE, Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points trial; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; EWPHE, European Working Party on High Blood Pressure in the Elderly study; HAPPHY, Heart Attack Primary Prevention in Hypertension trial; HBP, high blood pressure; HDFP, Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program; HOT, Hypertension Optimal Treatment study; INSIGHT, International Nifedipine GITS Study of Intervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment; I-PRESERVE, Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Systolic Function study; ISH, isolated systolic hypertension; LIFE, Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension trial; MAPHY, Metoprolol Atherosclerosis Prevention in Hypertensives study; MRC-1, Medical Research Council trial of treatment of mild hypertension; MRC-2, Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults; NORDIL, Nordic Diltiazem study; ONTARGET, Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial; SCOPE, Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly; SHEP, Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program; STOP-1, Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-1; STOP-2, Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-2; Syst-China, Systolic Hypertension in China trial; Syst-Eur, Systolic Hypertension in Europe trial; TOMHS, Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study; TROPHY, Trial of Preventing Hypertension; UKPDS, United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study; VA, Veterans Administration; VA MONORx, VA Monotherapy of Hypertension study; VALUE, Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation trial.Although the Framingham Study (www.framinghamheartstudy.org) was, of course, one of the seminal studies in the field of CV medicine, it was observational in nature, rather than interventional like most of the studies highlighted in this article.

The Medical Research Council trial of the treatment of mild hypertension (MRC-1) (ie, defined as DBP 90-109 mm Hg) demonstrated that a significant reduction in DBP among individuals receiving the diuretic bendroflumethiazide or the beta-blocker propranolol significantly reduced the rate of stroke compared with placebo, with a rate of 1.4 per 1000 patient-years of observation in the treatment group vs 2.6 per 1000 patient-years in the placebo group (P < .01).5 The treatment group also had significantly lower rates of all CV events than the placebo group, and this difference was statistically significant (P < .05). However, the treatment groups experienced significantly increased rates of adverse effects compared with placebo.5

Other early notable clinical trials that evaluated treatment options for hypertension in the general public include the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program (HDFP),3 the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) study,16 and the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study/Hypertension in Diabetes (UKPDS/HDS).17,18 The key outcomes of these trials are shown in TABLE 1.3,4,11,12,16,20,22,25,39,40

TABLE 1

Findings from the early clinical trials in hypertension

| Clinical Trial | Intervention | Primary Outcome | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDFP3,39 | Patients randomized to systemic antihypertensive treatment or community medical therapy (referral) | 5-year mortality | 5-year mortality reduced by 17% in treatment group (P < 0.01); after 12 years, BP still higher in treatment than in stepped-care treatment group |

| HOT16 | Patients all began on felodipine, with an ACEI or a BB added as necessary If BP goal was still not reached, HCTZ could be added Patients in each group also randomized to low-dose aspirin or placebo Subjects were randomly assigned to reach 1 of 3 DBP goals: ≤90 mm Hg; ≤85 mm Hg; or ≤80 mm Hg | Major CV events with 3 target DBPs reached during therapy and with low-dose aspirin therapy | Lowest incidence of major CV events achieved at mean BP of 138.5/82.6 mm Hg; lowest risk of CV mortality achieved at mean BP of 138.8/86.5 mm Hg Low-dose aspirin reduced major CV events by 15% and all MI by 36%, although nonfatal major bleeding was twice as common with low-dose aspirin than with placebo |

| UKPDS/HDS17,18 | Patients with T2DM randomized to atenolol or captopril, with additional antihypertensive agents (other than ACEIs or BBs) allowed | Effect of tight BP control on diabetes-related complications, morbidity, and mortality | Tight BP control (<150/85 mm Hg) with either atenolol or captopril significantly reduced the risk of all endpoints, including risk of diabetes-related death or complication, stroke, MI, and heart failure |

| EWPHPE4 | Patients ≥60 years of age randomized to HCTZ + triamterene + methyldopa or placebo | CV and MI mortality; nonfatal CV events | Significant reduction in CV and MI mortality (P < .05) but not nonfatal CV events in treatment group vs placebo Found U-shaped relationship between mortality and SBP in treated group vs mortality and DBP in placebo group |

| MRC-212 | Patients 65-74 years of age randomized to atenolol + HCTZ or amiloride | Reduction in mortality and morbidity due to stroke and CHD and reduction in mortality due to all causes | Only the HCTZ group demonstrated a significant reduction in stroke, coronary events, and all CV events (P=.4, P=.0009, and P=.0005, respectively) |

| STOP-222 | Patients 70-84 years of age randomized to atenolol + HCTZ or amiloride; or to metoprolol or prinodolol | Incidence of fatal stroke, MI, or other CVD mortality | Similar reductions in BP, mortality, and major events in all treatment groups |

| SCOPE25 | Patients 70-89 years of age randomized to candesartan or placebo (open-label antihypertensive therapy added as needed and extensively used in control group) | Major CV events; secondary measures included CV death, nonfatal and fatal stroke and MI, cognitive function | Greater BP decreases in candesartan group but no significant risk reduction in major CV events between the 2 groups Significant reduction in nonfatal stroke (P=.04) and all stroke (P=.06) in the treatment group No other significant differences between the groups, although a post-hoc analysis found less cognitive decline among those with only mild cognitive impairment at baseline in the candesartan-treated group (P=.04)40 |

| SHEP11 | Patients ≥60 years of age randomized to chlorthalidone with or without atenolol or reserpine, with nifedipine as third-line therapy, or to placebo | Stroke; nonfatal MI, coronary death, major CV events, death due to all causes | Significant reduction in 5-year incidence of total stroke in active treatment group (P=.0003) and significant reduction in all secondary endpoints |

| Syst-Eur19 | Patients >60 years of age randomized to nitrendipine with possible addition of enalapril, HCTZ, or both, or to placebo | Fatal and nonfatal stroke, fatal and nonfatal cardiac events including sudden death, all-cause mortality | Significant reductions in all endpoints except all-cause mortality in treatment group; study halted early because of the 42% total stroke reduction in treatment arm (P < .003) |

| Syst-China20 | Patients ≥60 years of age randomized to nitrendipine with captopril or HCTZ, or both if needed; or matching placebo | Nonfatal stroke; all-cause, CV, and stroke mortality; and all fatal and nonfatal CV events | Significant reductions in all endpoints |

| ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; BB, beta-blocker; BP, blood pressure; CV, cardiovascular; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, CV disease; DBP, diastolic BP; EWPHE, European Working Party on High Blood Pressure in the Elderly study; HDFP, Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program; HCTZ, hydrochlorothiazide; HOT, Hypertension Optimal Treatment study; MI, myocardial infarction; MRC-2, Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults; SBP, systolic BP; SCOPE, Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly; SHEP, Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program; STOP-2, Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-2; Syst-Eur, Systolic Hypertension in Europe trial; Syst-China, Systolic Hypertension in China trial; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; UKPDS/HDS, United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study/Hypertension in Diabetes. | |||

Given that hypertension is far more common in older people who have increased rates of hypertensive target organ damage or CV disease (CVD), researchers have focused on the effects of antihypertensive therapy in this population for some time.41 Sentinel studies in this population include the European Working Party on High Blood Pressure in the Elderly (EWPHPE) study,4 the Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults (MRC-2),12 the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-2 (STOP-2),22 the Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE),25 the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) study,11 the Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) study,19 and the Systolic Hypertension in China (Syst-China) study.20 The key outcomes of these trials are shown in TABLE 1. In general, these trials have shown that antihypertensive therapy has a marked benefit in a shorter period of time in older patients than in younger patients, particularly in terms of reduced stroke and CHF rates.

The Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET), which enrolled participants 80 years of age and older, demonstrated that reducing systolic BP (SBP) from 170 mm Hg to 145 mm Hg with indapamide sustained release 1.5 mg and perindopril 2 to 4 mg as needed reduced all-cause deaths 21% (P =.02), stroke-related deaths 39% (P =.05), and fatal and nonfatal heart failure (HF) 64% (P < .001), compared with placebo.42 The intervention group also experienced a 34% reduction in all CV events (P < .001) and a 30% reduction in stroke (P =.055).42 However, there is still no good evidence that reducing BP further in this population provides additional benefits over the concomitant risks.

In the 1980s, numerous trials were developed to address the question: “What is the best way to treat high BP?” These included the Heart Attack Primary Prevention in Hypertension (HAPPHY) trial,7 the Metoprolol Atherosclerosis Prevention in Hypertensives (MAPHY) study,8-10 the Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study (TOMHS),14 and the VA Cooperative Study on single drug therapy.15

Subsequently, several trials were conducted that focused on the safety of calcium antagonists for the primary or background treatment of hypertension. These included the International Nifedipine GITS Study of Intervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment (INSIGHT),23 the Nordic Diltiazem (NORDIL) study,24 the Australian National Blood Pressure Study 2 (ANBP2),28 the Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points (CONVINCE) trial,26 the Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) trial,29 and the Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Systolic Function (I-PRESERVE) study.37

These studies, conducted from the mid 1990s to the present, have shown that calcium antagonists, including amlodipine, diltiazem, nifedipine, and verapamil, are as effective as thiazide-type diuretics or beta-blockers in preventing CV events in patients with hypertension. Further, the LIFE trial demonstrated that the angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) losartan was more effective than the beta-blocker atenolol in reducing stroke events and that blockade of the renin- angiotensin system did not seem to affect CV outcomes in patients with HF with preserved systolic function, a common problem in patients with prolonged hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy.29

The largest randomized, double-blind, antihypertensive trial performed to date is the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). It involved 33,357 participants 55 years of age and older with hypertension and at least 1 other coronary heart disease (CHD) risk factor.27 Participants were randomized to chlorthalidone, amlodipine, doxazosin, or lisinopril. The doxazosin arm was discontinued early because an increase in CV events was observed after 2 years, relative to the other treatment arms. At follow-up (mean, 4.9 years), there was no difference between the 3 groups in terms of the primary outcome (combined fatal CHD or nonfatal myocardial infarction [MI], analyzed by intent-to-treat) or all-cause mortality.27 Of note, 5-year SBP levels were higher in the amlodipine (0.8 mm Hg, P=.03) and lisinopril (2 mm Hg, P < .001) groups than in the chlorthalidone group, whereas the 5-year DBP levels were significantly lower in the amlodipine group (0.8 mm Hg, P < .001).27

Secondary analyses showed a higher 6-year rate of HF development in the amlodipine group than in the chlorthali-done group (10.2% vs 7.7%; relative risk [RR], 1.38; 95% con- fidence interval [CI], 1.25-1.52), whereas the lisinopril group had a higher 6-year rate of combined CVD (33.3% vs 30.9%; RR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.05-1.16), stroke (6.3% vs 5.6%; RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.02-1.30), and HF (8.7% vs 7.7%; RR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.07-1.31) than the chlorthalidone group. The design of ALLHAT led to worsened control of BP in African Americans relative to white patients who were receiving lisinopril, which may have been an important factor in the subsequent increased rate of stroke in African American patients who were receiving lisinopril rather than chlorthalidone.27

Subsequent to ALLHAT, the benefits and safety of calcium antagonists vs a thiazide diuretic combined with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) were ad-dressed by the Avoiding Cardiovascular Events Through Combination Therapy in Patients Living With Systolic Hypertension (ACCOMPLISH) trial.33 This study randomized 11,506 patients with a mean BP of 145/80 mm Hg to combination therapy with benazepril (40 mg/d) and amlodipine (5-10 mg/d) or benazepril and HCTZ (12.5-25 mg/d). Other antihypertensive medications could be added to reach a target BP <140/90 mm Hg (130/80 mm Hg in patients with diabetes or renal insufficiency).33 The study was stopped early at 3 years because the primary outcome of CV death, nonfatal MI or stroke, hospitalization for angina, resuscitation after sudden cardiac arrest, and coronary revascularization occurred in 552 patients in the benazepril-amlodipine group compared with 679 patients in the benazepril-HCTZ group (9.6% vs 11.8%; RR ratio, 19.6%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.80; P < .001). The mechanism for the benefit observed in the benazepril-amlodipine group may relate in part to improved coronary blood flow that occurs with a calcium antagonist (compared with a diuretic) since BP control was virtually the same in both groups.

Another major hypertension study during the same era was the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT).32 This study enrolled 19,257 patients in northern Europe with a mean age of 63 years, an untreated baseline BP ≥160/100 mm Hg or a treated mean BP ≥140/90 mm Hg, and 3 or more of 11 prespecified risk factors for CV. Patients were randomized to amlodipine, with or without perindopril, or atenolol, with or without a thiazide diuretic, and were titrated to reach a BP goal <140/90 mm Hg. The study was halted early after a mean follow up of 5.5 years. Although there was no statistically significant difference in the primary events of nonfatal MI plus fatal CHF between the 2 arms, fewer patients randomized to the amlodipine-based regimen experienced a fatal or nonfatal stroke (327 vs 422; HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.66-0.89; P=.0003) and total CV events and procedures were lower in patients taking the amlodipine-based regimen than in those taking the atenolol-based regimen (1362 vs 1602; HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.78-0.90; P < .0001).32 All-cause mortality was also lower in the amlodipine-based group (738 vs 820; HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.81-0.99; P=.025), and significantly fewer patients in this arm developed diabetes (567 vs 799; HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.63-0.78; P < .0001).32

Patients with diabetes in ASCOT who were titrated to achieve a target BP <130/80 mm Hg experienced significantly lower mortality and stroke when taking the amlodipine-based regimen than when taking the atenolol-based regimen (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.76-0.98; P=.026).32 In the group taking the atenolol-based regimen, fatal and nonfatal strokes were reduced by 25% (P=.017), peripheral arterial disease by 48% (P=.004), and peripheral revascularization procedures by 57% (P < .001). There were no statistically significant differences in the endpoints of CHD deaths and nonfatal MI in the diabetes subgroup.

Combination therapy and guideline recommendations

By the 1970s, it became clear that combinations of antihypertensive drugs increased BP lowering efficacy through both additive and synergistic mechanisms. These combinations also reduced adverse events because lower doses of each drug could be used, whereas drugs from different classes might offset each other’s adverse effects. In addition, combining antihypertensive drugs could prolong duration of action, possibly providing additional target organ protection.43 Combining drugs from complementary classes has also been shown to increase the likelihood of BP lowering compared with increasing the dose of a single drug, thus reducing the time required to reach BP goal.31,44-46

The 2010 American Society of Hypertension (ASH) position statement on combination therapy in hypertension therapy notes that at least 75% of patients will require combination therapy to reach goal.47 In addition, a meta-analysis of 9 randomized clinical trials found that combination treatment using a thiazide or thiazide-like diuretic as one of the components could provide a significantly greater effect than monotherapy lacking the diuretic, with similar discontinuation rates.48

Government guidelines in the United States, now nearly 10 years old, do not recommend combination therapy as a first-line approach unless patients have stage 2 hypertension (SBP ≥160 mm Hg or DBP ≥100 mm Hg). At that point, the guidelines recommend combination therapy with a thiazide or thiazide-type diuretic plus either an ACEI, ARB, beta-blocker, or calcium antagonist.49 More-specific recommendations are provided for patients with compelling indications (eg, HF, ischemic heart disease, chronic kidney disease, recurrent stroke, diabetes, and high coronary disease risk), as shown in TABLE 2.41,49 New recommendations from the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 8) are expected later this year.

TABLE 2

Antihypertensive treatment in patients with compelling indications41,49

| Indication | Diuretic | BB | ACEI | ARB | Calcium antagonist | Aldosterone antagonist |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart failure | ||||||

| Post MI | ||||||

| CVD or high CVD risk | ||||||

| Anginaa | ||||||

| Aortopathy/aortic aneurysma | ||||||

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Recurrent stroke prevention | ||||||

| CKDb | ||||||

| Early dementiaa | ||||||

ACCF, American College of Cardiology Foundation; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AHA, American Heart Association; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; BB, beta-blocker; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; MI, myocardial infarction. aNot considered “compelling” indication in JNC-7 Express guidelines. bNot considered “compelling” recommendation in ACCF/AHA recommendations. Source: Journal of the American College of Cardiology by American College of Cardiology. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier Inc. in the format Journal via Copyright Clearance Center. | ||||||

Recent guidelines from ASH describe combination therapies of hypertension in categories of preferred, acceptable, and less effective, based on efficacy in lowering BP, safety and tolerability, and certain known outcomes from longer-term trials (TABLE 3).47

TABLE 3

Drug combinations in hypertension: Recommendations from the American Society of Hypertension47

| Preferred | Acceptable | Less Effective |

|---|---|---|

| ACEI + diuretica | BB + diuretica | ACEI + ARB |

| ARB + diuretica | Calcium antagonist + diuretic | ACEI + BB |

| ACEI + CCBa | Renin inhibitor + diuretic | ARB + BB |

| ARB + CCBa | Renin inhibitor + ARBa,b | CCB (non-dihydropyridine) + BB |

| Thiazide diuretic + potassium-sparing diuretica | Centrally acting agent + BB | |

| ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; BB, beta-blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker. aAvailable as single-pill combination. bThis may be medically inappropriate in patients with diabetes and chronic diabetic nephropathy. Source: Journal of the American Society of Hypertension: JASH by American Society of Hypertension. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier Inc. in the format Journal via Copyright Clearance Center. | ||

In 2010, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF)/American Heart Association (AHA) published an expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly. It recommends single therapy or combination therapy with an ACEI, ARB, calcium antagonist, or diuretic for patients 65 years of age and older with stage 1 hypertension and no “compelling” indications (eg, HF, post-MI, known coronary disease, angina, aortopathy/aortic aneurysm, diabetes, recurrent stroke prevention, chronic kidney disease, and early vascular dementia), but combination therapy for those with stage 2 hypertension and no compelling indications. For the former group, the panel notes that the combination of amlodipine with a renin-angiotensin aldosterone system blocker may be preferable to a diuretic combination, although either is acceptable.41

For patients with compelling indications, the ACCF/AHA panel recommends condition-based combination therapy with 2 or more of the therapies summarized in TABLE 2.41,49 The panel’s algorithm for the management of hypertension in the elderly is depicted in FIGURE 2.41

FIGURE 2

ACCF/AHA algorithm for the management of hypertension in the elderly41

ACCF, American College of Cardiology Foundation; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AHA, American Heart Association; ALDO ANT, aldosterone antagonist; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BB, beta-blocker; BP, blood pressure; CA, calcium antagonist; CAD, coronary artery disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DBP, diastolic BP; MI, myocardial infarction; RAS, renin-angiotensin system; SBP, systolic BP; THIAZ, thiazide diuretic.

aCombination therapy.

Source: Journal of the American College of Cardiology by American College of Cardiology. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier Inc. in the format Journal via Copyright Clearance Center.The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), the United Kingdom-based clinical guideline development organization, recommends in its 2011 guidelines for the clinical management of primary hypertension in adults that patients less than 55 years of age, not of black African or Caribbean heritage, begin treatment with an ACEI or ARB.50 The guidelines do not recommend beta-blockers for initial therapy, noting that they should be considered only in younger patients with intolerance or contraindications to ACEIs and ARBs, reproductive-aged women, and those with clinical evidence of increased sympathetic drive.50

In contrast, patients 55 years and older, or blacks of African or Caribbean origin of any age, should begin treatment with a calcium channel blocker (CCB).50 If they cannot tolerate a CCB, or for those with HF (or at high risk of HF), the guidelines recommend beginning therapy with a diuretic (preferably chlorthalidone or in-dapamide unless the patient’s hypertension is already controlled with bendroflumethiazide or HCTZ).

If initial treatment fails to lower BP adequately, step 2 of the NICE guidelines for all populations is treatment with an ACEI or ARB in combination with a calcium antagonist.50 If further therapy is necessary (step 3), a thiazide diuretic (or thiazide-like) should be added to that combination. It is also recommended that patients with drug-resistant hypertension (ie, taking 3 agents at maximally tolerated doses, 1 of which should be a diuretic) should receive additional treatment with low-dose spironolactone (if their serum potassium level is ≤4.5 mmol/L) and higher-dose thiazide-type diuretics (if their serum potassium level is >4.5 mmol/L). If the diuretic is not tolerated or is ineffective, an alpha- or beta-blocker may be added. If patients continue to exhibit continued resistance, NICE recommends referral to a hypertension specialist. The NICE algorithm for the treatment of hypertension is shown in FIGURE 3.50

FIGURE 3

NICE algorithm for treatment of hypertension50

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; NICE, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

aChoose a low-cost ARB.

bA CCB is preferred but consider a thiazide-like diuretic if a CCB is not tolerated or the person has edema, evidence of heart failure, or a high risk of heart failure.

cConsider a low dose of spironolactoned or higher doses of thiazide-like diuretic

dAt the time of publication (August 2011), spironolactone did not have a UK marketing authorization for this indication. Informed consent should be obtained and documented.

eConsider an alpha- or beta-blocker if further diuretic therapy is not tolerated or is contraindicated or ineffective.

Source: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2011) CG 127 Hypertension: clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. London: NICE. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG127. Reproduced with permission. The NICE guidance that this algorithm relates to was prepared for the National Health Service in England and Wales. NICE guidance does not apply to the United States and NICE has not been involved in the development or adaptation of any guidance for use in the United States.The ACCF/AHA and NICE guidelines also recommend that clinicians monitor electrolyte levels of patients on ACEIs/ARBs, with The frequency depending on each patient’s medical condition.41,50

Conclusion

With 7 major classes of antihypertensive drugs and several drugs within each class, there are numerous combinations available to clinicians to manage hypertension. Existing clinical trials cannot possibly evaluate all possible combinations. Yet, as noted in the ASH statement on combination therapy, the importance of achieving goal BP in individual patients cannot be overemphasized because small differences in on-treatment BP translate into major differences in the rates of CV events.47 When considering appropriate and effective antihypertensive therapies, clinicians should assess the evidence presented in this article and from the various clinical guidelines cited. Each patient is unique and it is important for clinicians to identify the most-effective treatment regimen for each individual patient.

1. Hamdy RC. Hypertension: a turning point in the history of medicine…and mankind. South Med J. 2001;94(11):1045-1047.

2. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents. Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg. JAMA. 1967;202(11):1028-1034.

3. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension. JAMA. 1979;242(23):2562-2571.

4. Amery A, De Schaepdryver A. The European Working Party on High Blood Pressure in the Elderly. Am J Med. 1991;90(3A):1S-4S.

5. Medical Research Council Working Party. MRC trial of treatment of mild hypertension: principal results. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;291(6488):97-104.

6. The Australian therapeutic trial in mild hypertension. Report by the Management Committee. Lancet. 1980;1(8181):1261-1267.

7. Wilhelmsen L, Berglund G, Elmfeldt D, et al. Beta-blockers versus diuretics in hypertensive men: main results from the HAPPHY trial. J Hypertens. 1987;5(5):561-572.

8. Wikstrand J, Berglund G, Tuomilehto J. Beta-blockade in the primary prevention of coronary heart disease in hypertensive patients. Review of present evidence. Circulation. 1991;84(6 Suppl):VI93-VI100.

9. Wikstrand J, Warnold I, Tuomilehto J, et al. Metoprolol versus thiazide diuretics in hypertension. Morbidity results from the MAPHY Study. Hypertension. 1991;17(4):579-588.

10. Olsson G, Tuomilehto J, Berglund G, et al. Primary prevention of sudden cardiovascular death in hypertensive patients. Mortality results from the MAPHY Study. Am J Hypertens. 1991;4(2 Pt 1):151-1511.

11. SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA. 1991;265(24):3255-3264.

12. MRC Working Party. Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults: principal results. BMJ. 1992;304(6824):405-412.

13. Dahlöf B, Lindholm LH, Hansson L, Scherstén B, Ekbom T, Wester PO. Morbidity and mortality in the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension (STOP-Hypertension). Lancet. 1991;338(8778):1281-1285.

14. Neaton JD, Grimm RH, Jr, Prineas RJ, et al. Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study Research Group. Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study. Final results. JAMA. 1993;270(6):713-724.

15. Materson BJ, Reda DJ, Cushman WC, et al. The Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents. Single-drug therapy for hypertension in men. A comparison of six antihypertensive agents with placebo [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 1994;330(23):1689]. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(13):914-921.

16. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. HOT Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet. 1998;351(9118):1755-1762.

17. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38 [published correction appears in BMJ. 1999;318(7175):29]. BMJ. 1998;317(7160):703-713.

18. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Efficacy of atenolol and captopril in reducing risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 39. BMJ. 1998;317(7160):713-720.

19. Staessen JA, Fagard R, Thijs L, et al. The Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial Investigators. Randomised double-blind comparison of placebo and active treatment for older patients with isolated systolic hypertension. Lancet. 1997;350(9080):757-764.

20. Liu L, Wang JG, Gong L, Liu G, Staessen JA. Systolic Hypertension in China (Syst-China) Collaborative Group. Comparison of active treatment and placebo in older Chinese patients with isolated systolic hypertension. J Hypertens. 1998;16(12 Pt 1):1823-1829.

21. Hansson L, Hedner T, Lindholm L, et al. The Captopril Prevention Project (CAPPP) in hypertension—baseline data and current status. Blood Press. 1997;6(6):365-367.

22. Hansson L, Lindholm LH, Ekbom T, et al. Randomised trial of old and new antihypertensive drugs in elderly patients: cardiovascular mortality and morbidity the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-2 study. Lancet. 1999;354(9192):1751-1756.

23. Brown MJ, Palmer CR, Castaigne A, et al. Morbidity and mortality in patients randomised to double-blind treatment with a long-acting calcium-channel blocker or diuretic in the International Nifedipine GITS study: Intervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment (INSIGHT) [published correction appears in Lancet. 2000;356(9228):514]. Lancet. 2000;356(9227):366-372.

24. Hansson L, Hedner T, Lund-Johansen P, et al. Randomised trial of effects of calcium antagonists compared with diuretics and beta-blockers on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hypertension: the Nordic Diltiazem (NORDIL) study. Lancet. 2000;356(9227):359-365.

25. Lithell H, Hansson L, Skoog I, et al. SCOPE Study Group. The Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE): principal results of a randomized double-blind intervention trial. J Hypertens. 2003;21(5):875-886.

26. Black HR, Elliott WJ, Grandits G, et al. CONVINCE Research Group. Principal results of the Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points (CONVINCE) trial. JAMA. 2003;289(16):2073-2082.

27. ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) [published corrections appear in JAMA. 2003;289(2):178; JAMA. 2004;291(18):2196]. JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981-2997.

28. Wing LM, Reid CM, Ryan P, et al. Second Australian National Blood Pressure Study Group. A comparison of outcomes with angiotensin-converting– enzyme inhibitors and diuretics for hypertension in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(7):583-592.

29. Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, et al. LIFE Study Group. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002;359(9311):995-1003.

30. The ONTARGET Investigators. Telmisartan, ramipril, or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(15):1547-1559.

31. Weber MA, Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Blood pressure dependent and independent effects of antihypertensive treatment on clinical events in the VALUE Trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9426):2049-2051.

32. Dahlöf B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, et al. ASCOT Investigators. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9489):895-906.

33. Jamerson K, Bakris GL, Dahlöf B, et al. ACCOMPLISH Investigators. Exceptional early blood pressure control rates: the ACCOMPLISH trial. Blood Press. 2007;16(2):80-86.

34. Julius S, Nesbitt SD, Egan BM, et al. Trial of Preventing Hypertension (TROPHY) Study Investigators. Feasibility of treating prehypertension with an angiotensin-receptor blocker. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(16):1685-1697.

35. ATMOSPHERE study, [NCT00853658] ongoing trial. Trial-Results Center Web site. http://www.trialresultscenter.org/study9503-ATMOSPHERE.htm. Accessed March 28, 2012.

36. Parving HH, Brenner BM, McMurray JJ, et al. Aliskiren Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Using Cardio-Renal Endpoints (ALTITUDE): rationale and study design. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(5):1663-1671.

37. Massie BM, Carson PE, McMurray JJ, et al. I-PRESERVE Investigators. Irbesartan in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(23):2456-2467.

38. US National Library of Medicine. The Edward D. Freis Papers: the VA Cooperative Study and the Beginning of Routine Hypertension Screening, 1964-1980. http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/retrieve/Narrative/XF/p-nid/172. Accessed March 26, 2012.

39. Comberg HU, Heyden S, Knowles M, et al. Long-term survey of 450 hypertensives of the HDFP. Munch Med Wochenschr. 1991;133:32-38.

40. Skoog I, Lithell H, Hansson L, et al. SCOPE Study Group. Effect of baseline cognitive function and antihypertensive treatment on cognitive and cardiovascular outcomes: Study on COgnition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE). Am J Hypertens. 2005;18(8):1052-1059.

41. Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, et al. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology, Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(20):2037-2114.

42. Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al. HYVET Study Group. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(18):1887-1898.

43. Weber MA, Neutel JM, Frishman WH. Combination drug therapy. In: Frishman WH, Sonnenblick EH, Sica DA, eds. Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapeutics. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003:355–368.

44. Pepine CJ, Handberg EM, Cooper-DeHoff RM, et al. INVEST Investigators. A calcium antagonist vs a non-calcium antagonist hypertension treatment strategy for patients with coronary artery disease. The International Verapamil- Trandolapril Study (INVEST): a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(21):2805-2816.

45. Mancia G, Messerli F, Bakris G, Zhou Q, Champion A, Pepine CJ. Blood pressure control and improved cardiovascular outcomes in the International Verapamil SR-Trandolapril Study. Hypertension. 2007;50(2):299-305.

46. Wald DS, Law M, Morris JK, Bestwick JP, Wald NJ. Combination therapy versus monotherapy in reducing blood pressure: meta-analysis on 11,000 participants from 42 trials. Am J Med. 2009;122(3):290-300.

47. Gradman AH, Basile JN, Carter BL, et al. Combination therapy in hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2010;4(2):90-98.

48. Weir MR, Levy D, Crikelair N, Rocha R, Meng X, Glazer R. Time to achieve blood-pressure goal: influence of dose of valsartan monotherapy and valsartan and hydrochlorothiazide combination therapy. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20(7):807-815.

49. National Heart, . Lung, and Blood Institute. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/. Published 2003. Accessed March 27, 2012.

50. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Hypertension: Clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13561/56008/56008.pdf. Published August 2011. Accessed March 27, 2012.

MODULE 1: Historical Review of Evidence-Based Treatment of Hypertension

MODULE 3: Using Thiazide-Type Diuretics in African Americans with Hypertension

Dr White is President of the American Society of Hypertension (voluntary unpaid position) and is a paid cardiovascular safety consultant to Abbott Immunology; Ardea Biosciences, Inc; AstraZeneca; BioSante Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Forest Research Institute, Inc; Novartis Corporation; Roche Laboratories, Inc; and Takeda Global Research & Development Center, Inc. He holds no stocks in pharmaceutical companies and is not a member of any speakers’ bureaus.

Introduction

Hypertension is a transformative condition in modern medicine due to the various numeric definitions of the disease, the decision of when to initiate therapy and to what level to treat, and the evolution of our understanding of the long-term complications of the hypertensive disease process. Hypertension is notable as 1 of the first conditions that only rarely manifested symptoms and whose eventual sequelae could take years, if not decades, to become known. In addition, hypertension was the first condition in which clinicians initiated therapy for patients who were otherwise healthy. Hypertension also led to 1 of the first screening programs for any disease as well as the first robust preventive effort for a chronic medical condition.1

Clinical trials have been performed for 5 decades to evaluate the potential benefits of lowering blood pressure (BP) in patients with hypertension and its comorbid conditions (FIGURE 1).2-37 The first clinical trial to identify the increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) mortality related to hypertension was published in the mid-1960s.2,38 In fact, the Veterans Administration (VA) Cooperative trial was the first randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multi-institutional drug efficacy trial ever conducted in CV medicine.38 It involved 143 men who met the 1964 definition of hypertension (ie, diastolic BP [DBP] ≥115 mm Hg) and who were randomized to either triple therapy with low doses of hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), reserpine, and hydralazine, or to placebo. The trial was terminated early when, after 18 months of treatment, rates of morbidity and mortality were substantially lower in the treated group than in the placebo group.2 The trial was the first to confirm that antihypertensive treatment, even in patients with existing CV damage and significant hypertension, could dramatically reduce the incidence of stroke, congestive heart failure (CHF), and progressive kidney damage.38

FIGURE 1

Clinical trials in hypertension during the past 5 decades

ACCOMPLISH, Avoiding Cardiovascular Events Through Combination Therapy in Patients Living With Systolic Hypertension trial; ALLHAT, Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial; ALTITUDE, Aliskiren Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Using Cardiovascular and Renal Disease Endpoints; ANBP1, Australian National Blood Pressure Study 1; ANBP2, Australian National Blood Pressure Study 2; ASCOT, Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial; ATMOSPHERE, Efficacy and Safety of Aliskiren and Aliskiren/Enalapril Combination on Morbi-mortality in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure study; CAPPP, Captopril Prevention Project; CONVINCE, Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points trial; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; EWPHE, European Working Party on High Blood Pressure in the Elderly study; HAPPHY, Heart Attack Primary Prevention in Hypertension trial; HBP, high blood pressure; HDFP, Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program; HOT, Hypertension Optimal Treatment study; INSIGHT, International Nifedipine GITS Study of Intervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment; I-PRESERVE, Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Systolic Function study; ISH, isolated systolic hypertension; LIFE, Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension trial; MAPHY, Metoprolol Atherosclerosis Prevention in Hypertensives study; MRC-1, Medical Research Council trial of treatment of mild hypertension; MRC-2, Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults; NORDIL, Nordic Diltiazem study; ONTARGET, Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial; SCOPE, Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly; SHEP, Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program; STOP-1, Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-1; STOP-2, Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-2; Syst-China, Systolic Hypertension in China trial; Syst-Eur, Systolic Hypertension in Europe trial; TOMHS, Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study; TROPHY, Trial of Preventing Hypertension; UKPDS, United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study; VA, Veterans Administration; VA MONORx, VA Monotherapy of Hypertension study; VALUE, Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation trial.Although the Framingham Study (www.framinghamheartstudy.org) was, of course, one of the seminal studies in the field of CV medicine, it was observational in nature, rather than interventional like most of the studies highlighted in this article.

The Medical Research Council trial of the treatment of mild hypertension (MRC-1) (ie, defined as DBP 90-109 mm Hg) demonstrated that a significant reduction in DBP among individuals receiving the diuretic bendroflumethiazide or the beta-blocker propranolol significantly reduced the rate of stroke compared with placebo, with a rate of 1.4 per 1000 patient-years of observation in the treatment group vs 2.6 per 1000 patient-years in the placebo group (P < .01).5 The treatment group also had significantly lower rates of all CV events than the placebo group, and this difference was statistically significant (P < .05). However, the treatment groups experienced significantly increased rates of adverse effects compared with placebo.5

Other early notable clinical trials that evaluated treatment options for hypertension in the general public include the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program (HDFP),3 the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) study,16 and the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study/Hypertension in Diabetes (UKPDS/HDS).17,18 The key outcomes of these trials are shown in TABLE 1.3,4,11,12,16,20,22,25,39,40

TABLE 1

Findings from the early clinical trials in hypertension

| Clinical Trial | Intervention | Primary Outcome | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDFP3,39 | Patients randomized to systemic antihypertensive treatment or community medical therapy (referral) | 5-year mortality | 5-year mortality reduced by 17% in treatment group (P < 0.01); after 12 years, BP still higher in treatment than in stepped-care treatment group |

| HOT16 | Patients all began on felodipine, with an ACEI or a BB added as necessary If BP goal was still not reached, HCTZ could be added Patients in each group also randomized to low-dose aspirin or placebo Subjects were randomly assigned to reach 1 of 3 DBP goals: ≤90 mm Hg; ≤85 mm Hg; or ≤80 mm Hg | Major CV events with 3 target DBPs reached during therapy and with low-dose aspirin therapy | Lowest incidence of major CV events achieved at mean BP of 138.5/82.6 mm Hg; lowest risk of CV mortality achieved at mean BP of 138.8/86.5 mm Hg Low-dose aspirin reduced major CV events by 15% and all MI by 36%, although nonfatal major bleeding was twice as common with low-dose aspirin than with placebo |

| UKPDS/HDS17,18 | Patients with T2DM randomized to atenolol or captopril, with additional antihypertensive agents (other than ACEIs or BBs) allowed | Effect of tight BP control on diabetes-related complications, morbidity, and mortality | Tight BP control (<150/85 mm Hg) with either atenolol or captopril significantly reduced the risk of all endpoints, including risk of diabetes-related death or complication, stroke, MI, and heart failure |

| EWPHPE4 | Patients ≥60 years of age randomized to HCTZ + triamterene + methyldopa or placebo | CV and MI mortality; nonfatal CV events | Significant reduction in CV and MI mortality (P < .05) but not nonfatal CV events in treatment group vs placebo Found U-shaped relationship between mortality and SBP in treated group vs mortality and DBP in placebo group |

| MRC-212 | Patients 65-74 years of age randomized to atenolol + HCTZ or amiloride | Reduction in mortality and morbidity due to stroke and CHD and reduction in mortality due to all causes | Only the HCTZ group demonstrated a significant reduction in stroke, coronary events, and all CV events (P=.4, P=.0009, and P=.0005, respectively) |

| STOP-222 | Patients 70-84 years of age randomized to atenolol + HCTZ or amiloride; or to metoprolol or prinodolol | Incidence of fatal stroke, MI, or other CVD mortality | Similar reductions in BP, mortality, and major events in all treatment groups |

| SCOPE25 | Patients 70-89 years of age randomized to candesartan or placebo (open-label antihypertensive therapy added as needed and extensively used in control group) | Major CV events; secondary measures included CV death, nonfatal and fatal stroke and MI, cognitive function | Greater BP decreases in candesartan group but no significant risk reduction in major CV events between the 2 groups Significant reduction in nonfatal stroke (P=.04) and all stroke (P=.06) in the treatment group No other significant differences between the groups, although a post-hoc analysis found less cognitive decline among those with only mild cognitive impairment at baseline in the candesartan-treated group (P=.04)40 |

| SHEP11 | Patients ≥60 years of age randomized to chlorthalidone with or without atenolol or reserpine, with nifedipine as third-line therapy, or to placebo | Stroke; nonfatal MI, coronary death, major CV events, death due to all causes | Significant reduction in 5-year incidence of total stroke in active treatment group (P=.0003) and significant reduction in all secondary endpoints |

| Syst-Eur19 | Patients >60 years of age randomized to nitrendipine with possible addition of enalapril, HCTZ, or both, or to placebo | Fatal and nonfatal stroke, fatal and nonfatal cardiac events including sudden death, all-cause mortality | Significant reductions in all endpoints except all-cause mortality in treatment group; study halted early because of the 42% total stroke reduction in treatment arm (P < .003) |

| Syst-China20 | Patients ≥60 years of age randomized to nitrendipine with captopril or HCTZ, or both if needed; or matching placebo | Nonfatal stroke; all-cause, CV, and stroke mortality; and all fatal and nonfatal CV events | Significant reductions in all endpoints |

| ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; BB, beta-blocker; BP, blood pressure; CV, cardiovascular; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, CV disease; DBP, diastolic BP; EWPHE, European Working Party on High Blood Pressure in the Elderly study; HDFP, Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program; HCTZ, hydrochlorothiazide; HOT, Hypertension Optimal Treatment study; MI, myocardial infarction; MRC-2, Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults; SBP, systolic BP; SCOPE, Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly; SHEP, Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program; STOP-2, Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-2; Syst-Eur, Systolic Hypertension in Europe trial; Syst-China, Systolic Hypertension in China trial; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; UKPDS/HDS, United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study/Hypertension in Diabetes. | |||

Given that hypertension is far more common in older people who have increased rates of hypertensive target organ damage or CV disease (CVD), researchers have focused on the effects of antihypertensive therapy in this population for some time.41 Sentinel studies in this population include the European Working Party on High Blood Pressure in the Elderly (EWPHPE) study,4 the Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults (MRC-2),12 the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-2 (STOP-2),22 the Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly (SCOPE),25 the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) study,11 the Systolic Hypertension in Europe (Syst-Eur) study,19 and the Systolic Hypertension in China (Syst-China) study.20 The key outcomes of these trials are shown in TABLE 1. In general, these trials have shown that antihypertensive therapy has a marked benefit in a shorter period of time in older patients than in younger patients, particularly in terms of reduced stroke and CHF rates.

The Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET), which enrolled participants 80 years of age and older, demonstrated that reducing systolic BP (SBP) from 170 mm Hg to 145 mm Hg with indapamide sustained release 1.5 mg and perindopril 2 to 4 mg as needed reduced all-cause deaths 21% (P =.02), stroke-related deaths 39% (P =.05), and fatal and nonfatal heart failure (HF) 64% (P < .001), compared with placebo.42 The intervention group also experienced a 34% reduction in all CV events (P < .001) and a 30% reduction in stroke (P =.055).42 However, there is still no good evidence that reducing BP further in this population provides additional benefits over the concomitant risks.

In the 1980s, numerous trials were developed to address the question: “What is the best way to treat high BP?” These included the Heart Attack Primary Prevention in Hypertension (HAPPHY) trial,7 the Metoprolol Atherosclerosis Prevention in Hypertensives (MAPHY) study,8-10 the Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study (TOMHS),14 and the VA Cooperative Study on single drug therapy.15

Subsequently, several trials were conducted that focused on the safety of calcium antagonists for the primary or background treatment of hypertension. These included the International Nifedipine GITS Study of Intervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment (INSIGHT),23 the Nordic Diltiazem (NORDIL) study,24 the Australian National Blood Pressure Study 2 (ANBP2),28 the Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points (CONVINCE) trial,26 the Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) trial,29 and the Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Systolic Function (I-PRESERVE) study.37

These studies, conducted from the mid 1990s to the present, have shown that calcium antagonists, including amlodipine, diltiazem, nifedipine, and verapamil, are as effective as thiazide-type diuretics or beta-blockers in preventing CV events in patients with hypertension. Further, the LIFE trial demonstrated that the angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) losartan was more effective than the beta-blocker atenolol in reducing stroke events and that blockade of the renin- angiotensin system did not seem to affect CV outcomes in patients with HF with preserved systolic function, a common problem in patients with prolonged hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy.29

The largest randomized, double-blind, antihypertensive trial performed to date is the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). It involved 33,357 participants 55 years of age and older with hypertension and at least 1 other coronary heart disease (CHD) risk factor.27 Participants were randomized to chlorthalidone, amlodipine, doxazosin, or lisinopril. The doxazosin arm was discontinued early because an increase in CV events was observed after 2 years, relative to the other treatment arms. At follow-up (mean, 4.9 years), there was no difference between the 3 groups in terms of the primary outcome (combined fatal CHD or nonfatal myocardial infarction [MI], analyzed by intent-to-treat) or all-cause mortality.27 Of note, 5-year SBP levels were higher in the amlodipine (0.8 mm Hg, P=.03) and lisinopril (2 mm Hg, P < .001) groups than in the chlorthalidone group, whereas the 5-year DBP levels were significantly lower in the amlodipine group (0.8 mm Hg, P < .001).27

Secondary analyses showed a higher 6-year rate of HF development in the amlodipine group than in the chlorthali-done group (10.2% vs 7.7%; relative risk [RR], 1.38; 95% con- fidence interval [CI], 1.25-1.52), whereas the lisinopril group had a higher 6-year rate of combined CVD (33.3% vs 30.9%; RR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.05-1.16), stroke (6.3% vs 5.6%; RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.02-1.30), and HF (8.7% vs 7.7%; RR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.07-1.31) than the chlorthalidone group. The design of ALLHAT led to worsened control of BP in African Americans relative to white patients who were receiving lisinopril, which may have been an important factor in the subsequent increased rate of stroke in African American patients who were receiving lisinopril rather than chlorthalidone.27

Subsequent to ALLHAT, the benefits and safety of calcium antagonists vs a thiazide diuretic combined with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) were ad-dressed by the Avoiding Cardiovascular Events Through Combination Therapy in Patients Living With Systolic Hypertension (ACCOMPLISH) trial.33 This study randomized 11,506 patients with a mean BP of 145/80 mm Hg to combination therapy with benazepril (40 mg/d) and amlodipine (5-10 mg/d) or benazepril and HCTZ (12.5-25 mg/d). Other antihypertensive medications could be added to reach a target BP <140/90 mm Hg (130/80 mm Hg in patients with diabetes or renal insufficiency).33 The study was stopped early at 3 years because the primary outcome of CV death, nonfatal MI or stroke, hospitalization for angina, resuscitation after sudden cardiac arrest, and coronary revascularization occurred in 552 patients in the benazepril-amlodipine group compared with 679 patients in the benazepril-HCTZ group (9.6% vs 11.8%; RR ratio, 19.6%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.80; P < .001). The mechanism for the benefit observed in the benazepril-amlodipine group may relate in part to improved coronary blood flow that occurs with a calcium antagonist (compared with a diuretic) since BP control was virtually the same in both groups.

Another major hypertension study during the same era was the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT).32 This study enrolled 19,257 patients in northern Europe with a mean age of 63 years, an untreated baseline BP ≥160/100 mm Hg or a treated mean BP ≥140/90 mm Hg, and 3 or more of 11 prespecified risk factors for CV. Patients were randomized to amlodipine, with or without perindopril, or atenolol, with or without a thiazide diuretic, and were titrated to reach a BP goal <140/90 mm Hg. The study was halted early after a mean follow up of 5.5 years. Although there was no statistically significant difference in the primary events of nonfatal MI plus fatal CHF between the 2 arms, fewer patients randomized to the amlodipine-based regimen experienced a fatal or nonfatal stroke (327 vs 422; HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.66-0.89; P=.0003) and total CV events and procedures were lower in patients taking the amlodipine-based regimen than in those taking the atenolol-based regimen (1362 vs 1602; HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.78-0.90; P < .0001).32 All-cause mortality was also lower in the amlodipine-based group (738 vs 820; HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.81-0.99; P=.025), and significantly fewer patients in this arm developed diabetes (567 vs 799; HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.63-0.78; P < .0001).32

Patients with diabetes in ASCOT who were titrated to achieve a target BP <130/80 mm Hg experienced significantly lower mortality and stroke when taking the amlodipine-based regimen than when taking the atenolol-based regimen (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.76-0.98; P=.026).32 In the group taking the atenolol-based regimen, fatal and nonfatal strokes were reduced by 25% (P=.017), peripheral arterial disease by 48% (P=.004), and peripheral revascularization procedures by 57% (P < .001). There were no statistically significant differences in the endpoints of CHD deaths and nonfatal MI in the diabetes subgroup.

Combination therapy and guideline recommendations

By the 1970s, it became clear that combinations of antihypertensive drugs increased BP lowering efficacy through both additive and synergistic mechanisms. These combinations also reduced adverse events because lower doses of each drug could be used, whereas drugs from different classes might offset each other’s adverse effects. In addition, combining antihypertensive drugs could prolong duration of action, possibly providing additional target organ protection.43 Combining drugs from complementary classes has also been shown to increase the likelihood of BP lowering compared with increasing the dose of a single drug, thus reducing the time required to reach BP goal.31,44-46

The 2010 American Society of Hypertension (ASH) position statement on combination therapy in hypertension therapy notes that at least 75% of patients will require combination therapy to reach goal.47 In addition, a meta-analysis of 9 randomized clinical trials found that combination treatment using a thiazide or thiazide-like diuretic as one of the components could provide a significantly greater effect than monotherapy lacking the diuretic, with similar discontinuation rates.48

Government guidelines in the United States, now nearly 10 years old, do not recommend combination therapy as a first-line approach unless patients have stage 2 hypertension (SBP ≥160 mm Hg or DBP ≥100 mm Hg). At that point, the guidelines recommend combination therapy with a thiazide or thiazide-type diuretic plus either an ACEI, ARB, beta-blocker, or calcium antagonist.49 More-specific recommendations are provided for patients with compelling indications (eg, HF, ischemic heart disease, chronic kidney disease, recurrent stroke, diabetes, and high coronary disease risk), as shown in TABLE 2.41,49 New recommendations from the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 8) are expected later this year.

TABLE 2

Antihypertensive treatment in patients with compelling indications41,49

| Indication | Diuretic | BB | ACEI | ARB | Calcium antagonist | Aldosterone antagonist |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart failure | ||||||

| Post MI | ||||||

| CVD or high CVD risk | ||||||

| Anginaa | ||||||

| Aortopathy/aortic aneurysma | ||||||

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Recurrent stroke prevention | ||||||

| CKDb | ||||||

| Early dementiaa | ||||||

ACCF, American College of Cardiology Foundation; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AHA, American Heart Association; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; BB, beta-blocker; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; MI, myocardial infarction. aNot considered “compelling” indication in JNC-7 Express guidelines. bNot considered “compelling” recommendation in ACCF/AHA recommendations. Source: Journal of the American College of Cardiology by American College of Cardiology. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier Inc. in the format Journal via Copyright Clearance Center. | ||||||

Recent guidelines from ASH describe combination therapies of hypertension in categories of preferred, acceptable, and less effective, based on efficacy in lowering BP, safety and tolerability, and certain known outcomes from longer-term trials (TABLE 3).47

TABLE 3

Drug combinations in hypertension: Recommendations from the American Society of Hypertension47

| Preferred | Acceptable | Less Effective |

|---|---|---|

| ACEI + diuretica | BB + diuretica | ACEI + ARB |

| ARB + diuretica | Calcium antagonist + diuretic | ACEI + BB |

| ACEI + CCBa | Renin inhibitor + diuretic | ARB + BB |

| ARB + CCBa | Renin inhibitor + ARBa,b | CCB (non-dihydropyridine) + BB |

| Thiazide diuretic + potassium-sparing diuretica | Centrally acting agent + BB | |

| ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; BB, beta-blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker. aAvailable as single-pill combination. bThis may be medically inappropriate in patients with diabetes and chronic diabetic nephropathy. Source: Journal of the American Society of Hypertension: JASH by American Society of Hypertension. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier Inc. in the format Journal via Copyright Clearance Center. | ||

In 2010, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF)/American Heart Association (AHA) published an expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly. It recommends single therapy or combination therapy with an ACEI, ARB, calcium antagonist, or diuretic for patients 65 years of age and older with stage 1 hypertension and no “compelling” indications (eg, HF, post-MI, known coronary disease, angina, aortopathy/aortic aneurysm, diabetes, recurrent stroke prevention, chronic kidney disease, and early vascular dementia), but combination therapy for those with stage 2 hypertension and no compelling indications. For the former group, the panel notes that the combination of amlodipine with a renin-angiotensin aldosterone system blocker may be preferable to a diuretic combination, although either is acceptable.41

For patients with compelling indications, the ACCF/AHA panel recommends condition-based combination therapy with 2 or more of the therapies summarized in TABLE 2.41,49 The panel’s algorithm for the management of hypertension in the elderly is depicted in FIGURE 2.41

FIGURE 2

ACCF/AHA algorithm for the management of hypertension in the elderly41

ACCF, American College of Cardiology Foundation; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AHA, American Heart Association; ALDO ANT, aldosterone antagonist; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; BB, beta-blocker; BP, blood pressure; CA, calcium antagonist; CAD, coronary artery disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DBP, diastolic BP; MI, myocardial infarction; RAS, renin-angiotensin system; SBP, systolic BP; THIAZ, thiazide diuretic.

aCombination therapy.

Source: Journal of the American College of Cardiology by American College of Cardiology. Reproduced with permission of Elsevier Inc. in the format Journal via Copyright Clearance Center.The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), the United Kingdom-based clinical guideline development organization, recommends in its 2011 guidelines for the clinical management of primary hypertension in adults that patients less than 55 years of age, not of black African or Caribbean heritage, begin treatment with an ACEI or ARB.50 The guidelines do not recommend beta-blockers for initial therapy, noting that they should be considered only in younger patients with intolerance or contraindications to ACEIs and ARBs, reproductive-aged women, and those with clinical evidence of increased sympathetic drive.50

In contrast, patients 55 years and older, or blacks of African or Caribbean origin of any age, should begin treatment with a calcium channel blocker (CCB).50 If they cannot tolerate a CCB, or for those with HF (or at high risk of HF), the guidelines recommend beginning therapy with a diuretic (preferably chlorthalidone or in-dapamide unless the patient’s hypertension is already controlled with bendroflumethiazide or HCTZ).

If initial treatment fails to lower BP adequately, step 2 of the NICE guidelines for all populations is treatment with an ACEI or ARB in combination with a calcium antagonist.50 If further therapy is necessary (step 3), a thiazide diuretic (or thiazide-like) should be added to that combination. It is also recommended that patients with drug-resistant hypertension (ie, taking 3 agents at maximally tolerated doses, 1 of which should be a diuretic) should receive additional treatment with low-dose spironolactone (if their serum potassium level is ≤4.5 mmol/L) and higher-dose thiazide-type diuretics (if their serum potassium level is >4.5 mmol/L). If the diuretic is not tolerated or is ineffective, an alpha- or beta-blocker may be added. If patients continue to exhibit continued resistance, NICE recommends referral to a hypertension specialist. The NICE algorithm for the treatment of hypertension is shown in FIGURE 3.50

FIGURE 3

NICE algorithm for treatment of hypertension50

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; NICE, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

aChoose a low-cost ARB.

bA CCB is preferred but consider a thiazide-like diuretic if a CCB is not tolerated or the person has edema, evidence of heart failure, or a high risk of heart failure.

cConsider a low dose of spironolactoned or higher doses of thiazide-like diuretic

dAt the time of publication (August 2011), spironolactone did not have a UK marketing authorization for this indication. Informed consent should be obtained and documented.

eConsider an alpha- or beta-blocker if further diuretic therapy is not tolerated or is contraindicated or ineffective.

Source: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2011) CG 127 Hypertension: clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. London: NICE. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG127. Reproduced with permission. The NICE guidance that this algorithm relates to was prepared for the National Health Service in England and Wales. NICE guidance does not apply to the United States and NICE has not been involved in the development or adaptation of any guidance for use in the United States.The ACCF/AHA and NICE guidelines also recommend that clinicians monitor electrolyte levels of patients on ACEIs/ARBs, with The frequency depending on each patient’s medical condition.41,50

Conclusion

With 7 major classes of antihypertensive drugs and several drugs within each class, there are numerous combinations available to clinicians to manage hypertension. Existing clinical trials cannot possibly evaluate all possible combinations. Yet, as noted in the ASH statement on combination therapy, the importance of achieving goal BP in individual patients cannot be overemphasized because small differences in on-treatment BP translate into major differences in the rates of CV events.47 When considering appropriate and effective antihypertensive therapies, clinicians should assess the evidence presented in this article and from the various clinical guidelines cited. Each patient is unique and it is important for clinicians to identify the most-effective treatment regimen for each individual patient.

MODULE 1: Historical Review of Evidence-Based Treatment of Hypertension

MODULE 3: Using Thiazide-Type Diuretics in African Americans with Hypertension

Dr White is President of the American Society of Hypertension (voluntary unpaid position) and is a paid cardiovascular safety consultant to Abbott Immunology; Ardea Biosciences, Inc; AstraZeneca; BioSante Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Forest Research Institute, Inc; Novartis Corporation; Roche Laboratories, Inc; and Takeda Global Research & Development Center, Inc. He holds no stocks in pharmaceutical companies and is not a member of any speakers’ bureaus.

Introduction

Hypertension is a transformative condition in modern medicine due to the various numeric definitions of the disease, the decision of when to initiate therapy and to what level to treat, and the evolution of our understanding of the long-term complications of the hypertensive disease process. Hypertension is notable as 1 of the first conditions that only rarely manifested symptoms and whose eventual sequelae could take years, if not decades, to become known. In addition, hypertension was the first condition in which clinicians initiated therapy for patients who were otherwise healthy. Hypertension also led to 1 of the first screening programs for any disease as well as the first robust preventive effort for a chronic medical condition.1

Clinical trials have been performed for 5 decades to evaluate the potential benefits of lowering blood pressure (BP) in patients with hypertension and its comorbid conditions (FIGURE 1).2-37 The first clinical trial to identify the increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) mortality related to hypertension was published in the mid-1960s.2,38 In fact, the Veterans Administration (VA) Cooperative trial was the first randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multi-institutional drug efficacy trial ever conducted in CV medicine.38 It involved 143 men who met the 1964 definition of hypertension (ie, diastolic BP [DBP] ≥115 mm Hg) and who were randomized to either triple therapy with low doses of hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), reserpine, and hydralazine, or to placebo. The trial was terminated early when, after 18 months of treatment, rates of morbidity and mortality were substantially lower in the treated group than in the placebo group.2 The trial was the first to confirm that antihypertensive treatment, even in patients with existing CV damage and significant hypertension, could dramatically reduce the incidence of stroke, congestive heart failure (CHF), and progressive kidney damage.38

FIGURE 1

Clinical trials in hypertension during the past 5 decades

ACCOMPLISH, Avoiding Cardiovascular Events Through Combination Therapy in Patients Living With Systolic Hypertension trial; ALLHAT, Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial; ALTITUDE, Aliskiren Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Using Cardiovascular and Renal Disease Endpoints; ANBP1, Australian National Blood Pressure Study 1; ANBP2, Australian National Blood Pressure Study 2; ASCOT, Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial; ATMOSPHERE, Efficacy and Safety of Aliskiren and Aliskiren/Enalapril Combination on Morbi-mortality in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure study; CAPPP, Captopril Prevention Project; CONVINCE, Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points trial; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; EWPHE, European Working Party on High Blood Pressure in the Elderly study; HAPPHY, Heart Attack Primary Prevention in Hypertension trial; HBP, high blood pressure; HDFP, Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program; HOT, Hypertension Optimal Treatment study; INSIGHT, International Nifedipine GITS Study of Intervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment; I-PRESERVE, Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Systolic Function study; ISH, isolated systolic hypertension; LIFE, Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension trial; MAPHY, Metoprolol Atherosclerosis Prevention in Hypertensives study; MRC-1, Medical Research Council trial of treatment of mild hypertension; MRC-2, Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults; NORDIL, Nordic Diltiazem study; ONTARGET, Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination with Ramipril Global Endpoint Trial; SCOPE, Study on Cognition and Prognosis in the Elderly; SHEP, Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program; STOP-1, Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-1; STOP-2, Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-2; Syst-China, Systolic Hypertension in China trial; Syst-Eur, Systolic Hypertension in Europe trial; TOMHS, Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study; TROPHY, Trial of Preventing Hypertension; UKPDS, United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study; VA, Veterans Administration; VA MONORx, VA Monotherapy of Hypertension study; VALUE, Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation trial.Although the Framingham Study (www.framinghamheartstudy.org) was, of course, one of the seminal studies in the field of CV medicine, it was observational in nature, rather than interventional like most of the studies highlighted in this article.

The Medical Research Council trial of the treatment of mild hypertension (MRC-1) (ie, defined as DBP 90-109 mm Hg) demonstrated that a significant reduction in DBP among individuals receiving the diuretic bendroflumethiazide or the beta-blocker propranolol significantly reduced the rate of stroke compared with placebo, with a rate of 1.4 per 1000 patient-years of observation in the treatment group vs 2.6 per 1000 patient-years in the placebo group (P < .01).5 The treatment group also had significantly lower rates of all CV events than the placebo group, and this difference was statistically significant (P < .05). However, the treatment groups experienced significantly increased rates of adverse effects compared with placebo.5

Other early notable clinical trials that evaluated treatment options for hypertension in the general public include the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program (HDFP),3 the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) study,16 and the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study/Hypertension in Diabetes (UKPDS/HDS).17,18 The key outcomes of these trials are shown in TABLE 1.3,4,11,12,16,20,22,25,39,40

TABLE 1

Findings from the early clinical trials in hypertension

| Clinical Trial | Intervention | Primary Outcome | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDFP3,39 | Patients randomized to systemic antihypertensive treatment or community medical therapy (referral) | 5-year mortality | 5-year mortality reduced by 17% in treatment group (P < 0.01); after 12 years, BP still higher in treatment than in stepped-care treatment group |