User login

A 23-year-old woman presents with an 18-month history of a lesion on her heel that has persisted despite treatment with an OTC salicylic acid preparation, several attempts with an OTC “freezing unit,” and cryotherapy performed by her primary care provider. The lesion is continually aggravated by weight-bearing.

As a child, she reports, she had several warts on her hands. However, they resolved without treatment.

EXAMINATION

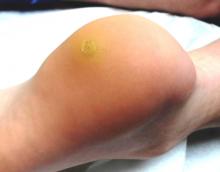

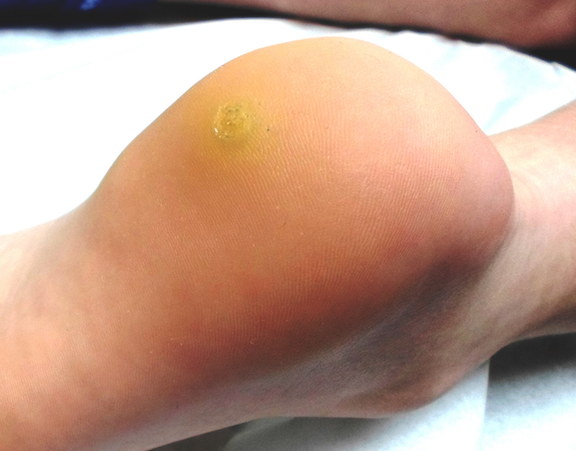

The lesion in question is almost 1 cm in diameter and clearly intradermal in nature. It has a rough, dry feel. On its surface, there are tiny black dots. Normal skin lines flow over the surface of the heel until they reach the lesion; at that point, they curve around its periphery and rejoin on the other side.

DISCUSSION

These features—the black dots, which represent vertically aligned thrombosed capillaries, and the curving skin lines—are diagnostic for plantar warts. This case represents a classic plantar (not “planter”) wart, so named because of its location, not because it has anything to do with planting.

There are good reasons for distinguishing plantar from ordinary warts. For one thing, the outer layer of skin on the sole (the stratum lucidum) is avascular and quite thick, allowing the wart not only to become relatively deep but also to escape detection by the immune system. Since they are almost always on the weight-bearing surface of the sole, even small warts can cause considerable discomfort as they grow.

These same features—the depth and location of the wart—also get in the way of successful treatment, since it may or may not reach the deep margin of the lesion without undue pain and scarring. As in other areas of medicine, we in dermatology strive to avoid treatments that are worse than the disease.

While this is especially true with children, many adults are intolerant of the usual liquid nitrogen treatment (cryotherapy), not only because of the pain associated with the initial application but also because the blistering and pain can persist for days afterward. Perhaps worst of all, no treatment modality is a “sure thing,” so the patient may go through the process and get very little in return.

This combination of issues is why, in dermatology, the first thing we do is to discuss the situation thoroughly with the patient (and parents). My typical conversation starts like this: “You know, you’ve brought us a very difficult problem to treat. This is an infection caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), which can grow deep and does not elicit much of an immune response. We don’t have drugs or shots to kill the virus. And, as if this were not enough of a problem, none of our treatment choices is remotely perfect. They might not work, and most are sure to cause pain.” Then, of course, I review the treatment options one by one.

TREATMENT

If the patient is lucky and the wart is small and shallow, we typically treat with a liquid nitrogen gun, almost always through a 3 to 5 mm speculum to concentrate the spray. We might shave down the surface of the wart with a #10 blade first, to reduce the thickness and increase the likelihood of successful treatment.

In my opinion, based on many years of treating these warts, using a cotton-tipped applicator to apply the liquid nitrogen is a waste of time and pain. Warts on thin-skinned areas such as arms and legs might be the exception.

Often, with small children, I discuss another option with the parents: that of doing nothing. Warts are warts, not dangerous in any way. Virtually all of them will eventually resolve on their own. The trouble is, of course, that we can’t promise when this will happen, or how big the wart might become in the interim.

There are nonpainful treatment choices, albeit ones with little chance of ultimate success. These include the OTC wart treatment products, virtually all of which contain salicylic acid as their main ingredient. Applied two or three times a week, these products can at least hold smaller warts in check, and could result in a cure.

Much the same could be said for products like cantharidin, a chemical derived from blister beetles, which causes nonpainful and slight blistering at the site. Unfortunately, we can’t prescribe it, which dooms the patient to returning to the office every two or three weeks. As with many such treatment options, it is unlikely to result in a cure.

Another treatment option is dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) as the main ingredient in a compounded product. DNCB is a potent T-cell stimulator—another way of saying that we can make the patient allergic to the substance, bringing the body’s immune system to bear on the treated area, producing slight blistering and hopefully destroying the wart in the process. It has to be used with caution, lest the substance wind up on unaffected skin. Parents need to understand that DNCB is slow to work (often taking a month or more) and again, by no means a sure thing. Squaric acid is an alternative to DNCB.

Surgical curettage and electrodessication, under local anesthesia, is potentially the most effective treatment we have for plantar warts—but as you might imagine, piercing the sole of a young child’s foot with a 30-gauge needle is rarely our first choice. It’s the method we used before liquid nitrogen was widely available, and it was a nightmare for all involved. Three outcomes were possible, two quite negative: Serious post-procedure pain and scarring were almost certain. But worst of all, the wart could easily return despite all that. The only time I use this is when the plantar wart is totally resistant to treatment and so large as to interfere with walking.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• The reason there are 20 or more treatments for warts is that none are remotely perfect.

• Plantar warts are a special problem because they develop on weight-bearing portions of the sole, growing inward (endophytic) in a thick skin layer that allows the virus to avoid detection by the immune system. Plantar warts often cause pain, which treatment can worsen.

• Parents/patients need to understand all of this prior to selecting an appropriate treatment choice.

• They also need to understand that warts do not have to be treated. Most will resolve on their own, eventually.

• Terrorizing children is to be avoided if at all possible. Parents may want their child’s warts to be “taken care of,” but they need to understand this may not be possible.

• Consider referral of problematic plantar warts to dermatology.

A 23-year-old woman presents with an 18-month history of a lesion on her heel that has persisted despite treatment with an OTC salicylic acid preparation, several attempts with an OTC “freezing unit,” and cryotherapy performed by her primary care provider. The lesion is continually aggravated by weight-bearing.

As a child, she reports, she had several warts on her hands. However, they resolved without treatment.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is almost 1 cm in diameter and clearly intradermal in nature. It has a rough, dry feel. On its surface, there are tiny black dots. Normal skin lines flow over the surface of the heel until they reach the lesion; at that point, they curve around its periphery and rejoin on the other side.

DISCUSSION

These features—the black dots, which represent vertically aligned thrombosed capillaries, and the curving skin lines—are diagnostic for plantar warts. This case represents a classic plantar (not “planter”) wart, so named because of its location, not because it has anything to do with planting.

There are good reasons for distinguishing plantar from ordinary warts. For one thing, the outer layer of skin on the sole (the stratum lucidum) is avascular and quite thick, allowing the wart not only to become relatively deep but also to escape detection by the immune system. Since they are almost always on the weight-bearing surface of the sole, even small warts can cause considerable discomfort as they grow.

These same features—the depth and location of the wart—also get in the way of successful treatment, since it may or may not reach the deep margin of the lesion without undue pain and scarring. As in other areas of medicine, we in dermatology strive to avoid treatments that are worse than the disease.

While this is especially true with children, many adults are intolerant of the usual liquid nitrogen treatment (cryotherapy), not only because of the pain associated with the initial application but also because the blistering and pain can persist for days afterward. Perhaps worst of all, no treatment modality is a “sure thing,” so the patient may go through the process and get very little in return.

This combination of issues is why, in dermatology, the first thing we do is to discuss the situation thoroughly with the patient (and parents). My typical conversation starts like this: “You know, you’ve brought us a very difficult problem to treat. This is an infection caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), which can grow deep and does not elicit much of an immune response. We don’t have drugs or shots to kill the virus. And, as if this were not enough of a problem, none of our treatment choices is remotely perfect. They might not work, and most are sure to cause pain.” Then, of course, I review the treatment options one by one.

TREATMENT

If the patient is lucky and the wart is small and shallow, we typically treat with a liquid nitrogen gun, almost always through a 3 to 5 mm speculum to concentrate the spray. We might shave down the surface of the wart with a #10 blade first, to reduce the thickness and increase the likelihood of successful treatment.

In my opinion, based on many years of treating these warts, using a cotton-tipped applicator to apply the liquid nitrogen is a waste of time and pain. Warts on thin-skinned areas such as arms and legs might be the exception.

Often, with small children, I discuss another option with the parents: that of doing nothing. Warts are warts, not dangerous in any way. Virtually all of them will eventually resolve on their own. The trouble is, of course, that we can’t promise when this will happen, or how big the wart might become in the interim.

There are nonpainful treatment choices, albeit ones with little chance of ultimate success. These include the OTC wart treatment products, virtually all of which contain salicylic acid as their main ingredient. Applied two or three times a week, these products can at least hold smaller warts in check, and could result in a cure.

Much the same could be said for products like cantharidin, a chemical derived from blister beetles, which causes nonpainful and slight blistering at the site. Unfortunately, we can’t prescribe it, which dooms the patient to returning to the office every two or three weeks. As with many such treatment options, it is unlikely to result in a cure.

Another treatment option is dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) as the main ingredient in a compounded product. DNCB is a potent T-cell stimulator—another way of saying that we can make the patient allergic to the substance, bringing the body’s immune system to bear on the treated area, producing slight blistering and hopefully destroying the wart in the process. It has to be used with caution, lest the substance wind up on unaffected skin. Parents need to understand that DNCB is slow to work (often taking a month or more) and again, by no means a sure thing. Squaric acid is an alternative to DNCB.

Surgical curettage and electrodessication, under local anesthesia, is potentially the most effective treatment we have for plantar warts—but as you might imagine, piercing the sole of a young child’s foot with a 30-gauge needle is rarely our first choice. It’s the method we used before liquid nitrogen was widely available, and it was a nightmare for all involved. Three outcomes were possible, two quite negative: Serious post-procedure pain and scarring were almost certain. But worst of all, the wart could easily return despite all that. The only time I use this is when the plantar wart is totally resistant to treatment and so large as to interfere with walking.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• The reason there are 20 or more treatments for warts is that none are remotely perfect.

• Plantar warts are a special problem because they develop on weight-bearing portions of the sole, growing inward (endophytic) in a thick skin layer that allows the virus to avoid detection by the immune system. Plantar warts often cause pain, which treatment can worsen.

• Parents/patients need to understand all of this prior to selecting an appropriate treatment choice.

• They also need to understand that warts do not have to be treated. Most will resolve on their own, eventually.

• Terrorizing children is to be avoided if at all possible. Parents may want their child’s warts to be “taken care of,” but they need to understand this may not be possible.

• Consider referral of problematic plantar warts to dermatology.

A 23-year-old woman presents with an 18-month history of a lesion on her heel that has persisted despite treatment with an OTC salicylic acid preparation, several attempts with an OTC “freezing unit,” and cryotherapy performed by her primary care provider. The lesion is continually aggravated by weight-bearing.

As a child, she reports, she had several warts on her hands. However, they resolved without treatment.

EXAMINATION

The lesion in question is almost 1 cm in diameter and clearly intradermal in nature. It has a rough, dry feel. On its surface, there are tiny black dots. Normal skin lines flow over the surface of the heel until they reach the lesion; at that point, they curve around its periphery and rejoin on the other side.

DISCUSSION

These features—the black dots, which represent vertically aligned thrombosed capillaries, and the curving skin lines—are diagnostic for plantar warts. This case represents a classic plantar (not “planter”) wart, so named because of its location, not because it has anything to do with planting.

There are good reasons for distinguishing plantar from ordinary warts. For one thing, the outer layer of skin on the sole (the stratum lucidum) is avascular and quite thick, allowing the wart not only to become relatively deep but also to escape detection by the immune system. Since they are almost always on the weight-bearing surface of the sole, even small warts can cause considerable discomfort as they grow.

These same features—the depth and location of the wart—also get in the way of successful treatment, since it may or may not reach the deep margin of the lesion without undue pain and scarring. As in other areas of medicine, we in dermatology strive to avoid treatments that are worse than the disease.

While this is especially true with children, many adults are intolerant of the usual liquid nitrogen treatment (cryotherapy), not only because of the pain associated with the initial application but also because the blistering and pain can persist for days afterward. Perhaps worst of all, no treatment modality is a “sure thing,” so the patient may go through the process and get very little in return.

This combination of issues is why, in dermatology, the first thing we do is to discuss the situation thoroughly with the patient (and parents). My typical conversation starts like this: “You know, you’ve brought us a very difficult problem to treat. This is an infection caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), which can grow deep and does not elicit much of an immune response. We don’t have drugs or shots to kill the virus. And, as if this were not enough of a problem, none of our treatment choices is remotely perfect. They might not work, and most are sure to cause pain.” Then, of course, I review the treatment options one by one.

TREATMENT

If the patient is lucky and the wart is small and shallow, we typically treat with a liquid nitrogen gun, almost always through a 3 to 5 mm speculum to concentrate the spray. We might shave down the surface of the wart with a #10 blade first, to reduce the thickness and increase the likelihood of successful treatment.

In my opinion, based on many years of treating these warts, using a cotton-tipped applicator to apply the liquid nitrogen is a waste of time and pain. Warts on thin-skinned areas such as arms and legs might be the exception.

Often, with small children, I discuss another option with the parents: that of doing nothing. Warts are warts, not dangerous in any way. Virtually all of them will eventually resolve on their own. The trouble is, of course, that we can’t promise when this will happen, or how big the wart might become in the interim.

There are nonpainful treatment choices, albeit ones with little chance of ultimate success. These include the OTC wart treatment products, virtually all of which contain salicylic acid as their main ingredient. Applied two or three times a week, these products can at least hold smaller warts in check, and could result in a cure.

Much the same could be said for products like cantharidin, a chemical derived from blister beetles, which causes nonpainful and slight blistering at the site. Unfortunately, we can’t prescribe it, which dooms the patient to returning to the office every two or three weeks. As with many such treatment options, it is unlikely to result in a cure.

Another treatment option is dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) as the main ingredient in a compounded product. DNCB is a potent T-cell stimulator—another way of saying that we can make the patient allergic to the substance, bringing the body’s immune system to bear on the treated area, producing slight blistering and hopefully destroying the wart in the process. It has to be used with caution, lest the substance wind up on unaffected skin. Parents need to understand that DNCB is slow to work (often taking a month or more) and again, by no means a sure thing. Squaric acid is an alternative to DNCB.

Surgical curettage and electrodessication, under local anesthesia, is potentially the most effective treatment we have for plantar warts—but as you might imagine, piercing the sole of a young child’s foot with a 30-gauge needle is rarely our first choice. It’s the method we used before liquid nitrogen was widely available, and it was a nightmare for all involved. Three outcomes were possible, two quite negative: Serious post-procedure pain and scarring were almost certain. But worst of all, the wart could easily return despite all that. The only time I use this is when the plantar wart is totally resistant to treatment and so large as to interfere with walking.

TAKE-AWAY LEARNING POINTS

• The reason there are 20 or more treatments for warts is that none are remotely perfect.

• Plantar warts are a special problem because they develop on weight-bearing portions of the sole, growing inward (endophytic) in a thick skin layer that allows the virus to avoid detection by the immune system. Plantar warts often cause pain, which treatment can worsen.

• Parents/patients need to understand all of this prior to selecting an appropriate treatment choice.

• They also need to understand that warts do not have to be treated. Most will resolve on their own, eventually.

• Terrorizing children is to be avoided if at all possible. Parents may want their child’s warts to be “taken care of,” but they need to understand this may not be possible.

• Consider referral of problematic plantar warts to dermatology.