User login

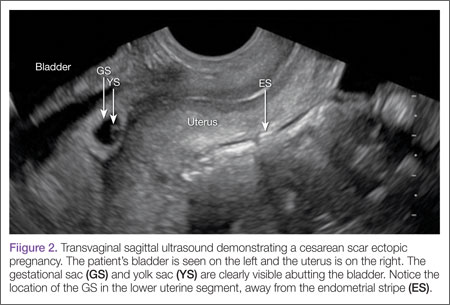

Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy (CSEP) is a challenging diagnosis that warrants consideration when performing ultrasound on a pregnant patient with a previous history of cesarean delivery. It is suspected when ballooning of the lower uterine segment is noted on ultrasound,1 when a trophoblast is seen at a presumed cesarean scar beneath the utero-vesicular fold, and when myometrium between the gestational sac and bladder wall is thin (<8 mm).2

Ectopic Pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy affects approximately 2% of all pregnancies and is the leading cause of first-trimester maternal mortality.3 As front-line care providers, it is imperative that emergency physicians (EPs) recognize cases of ectopic implantation to avoid devastating outcomes.

The majority of ectopic pregnancies (97%) are located in the fallopian tubes; however, many other locations are possible, including implantation in the scar from a previous cesarean delivery.1,4 The frequency of such ectopic pregnancies is on the rise, consistent with the increasing number of cesarean deliveries performed worldwide.5 These cases present a special diagnostic challenge because patients often present asymptomatically or with painless vaginal bleeding; moreover, visualization via bedside ultrasound can be deceiving,5 and it is easy to mistake a CSEP for a viable intrauterine pregnancy.

Case

A 22-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM) presented to the ED complaining of 3 days of worsening nausea and elevated blood glucose levels. She stated that although she had been taking her insulin regimen as prescribed, her symptoms progressively worsened. On the day of presentation, she developed moderate diffuse nonradiating dull abdominal pain and had several episodes of nonbloody, nonbilious emesis. She denied being pregnant and stated that her last menstrual period was 14 days ago; she further denied any vaginal discharge or bleeding. A review of her systems was otherwise benign.

In addition to type 1 DM, the patient also had a history of migraine headaches and an obstetric history of gravida 3, para 3, aborta 0. Each birth was via cesarean delivery and without complication. Her current medications included insulin glargine (Lantus) 25 units subcutaneously every night at bedtime; insulin aspart (Novolog) 7 units subcutaneously three times a day; zolpidem (Ambien) 10 mg orally every night at bedtime. A chart review was notable for several presentations of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) secondary to noncompliance with her diabetes regimen.

Physical examination was notable for a well-developed, well-nourished 22 year old that appeared uncomfortable but in no acute distress. Her abdomen was soft and nondistended, with diffuse moderate tenderness to palpation but no rebound or guarding. The remainder of the physical

The initial workup revealed DKA and pregnancy. Significant laboratory values included: finger-stick blood glucose, 441 mg/dL; serum ketones, 2.1 mmol/L (normal range, 0.0-0.5); anion gap, 15; and urinalysis 4+ glucose, 2+ ketones; and quantitative β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG), 5,282 IU/L (normal range, 0-5.0 IU/L ).examination was otherwise benign.

After receiving insulin, intravenous (IV) fluids, pain medication, and antiemetics, the patient stated she felt much better. She was then admitted to the inpatient floor for management of DKA and discharged uneventfully several days later. Emergency bedside transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasounds were performed by the emergency staff and identified an intrauterine gestational sac and yolk sac. The EP ordered a consultation with an obstetrician-gynecologist (OB-GYN), who saw the patient in the ED and agreed with the findings, and noted the gestational sac was consistent with a date of 5 weeks, 1 day.

Six days after discharge, however, she returned to the ED complaining of several days of weakness, vomiting, and lower abdominal pain. Significant laboratory values included: urinalysis with 4+ ketones, 1+ bacteria, + nitrites; and quantitative β-HCG 25,925 IU/L (expected range, 0-5.0); serum glucose 206 mg/dL; serum ketones 0.8 (expected range, 0-0.5); and anion gap, 12.

An emergency ultrasound identified a gestational sac, yolk sac, fetal pole, and fetal heart tones; an OB-GYN ultrasound had consistent findings, with an estimated gestational age of 6 weeks, 6 days. The patient responded well to IV fluids and antiemetics, and was asymptomatic when she was admitted to the ED observation unit for continued monitoring, fluids, and antiemetics as needed. Several hours later she again began to complain of nausea, vomiting, and poorly localized abdominal discomfort. As these symptoms persisted, the OB-GYN team returned to reevaluate the patient.

Discussion

Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy was first described in the obstetric literature in 1978 and originally thought to be an exceedingly rare occurrence.5,6 With both the increasing number of cesarean deliveries performed and improvement in imaging technology, it is now believed that uterine scar ectopic pregnancy makes up as much as 6.1% of ectopic pregnancies in patients with a prior cesarean delivery.7 This diagnosis is well-documented in the obstetric and radiology literature, yet has never been discussed in an emergency medicine publication. Searching through both Pubmed and EMBase using the terms “cesarean” and “ectopic” yields no EM literature on the topic of CSEP. This is concerning because ultrasound of the pregnant patient is now a routine function of EPs.

Clinical history can be helpful in differentiating CSEP from alternative diagnoses. Patients undergoing spontaneous abortion are more likely to have lower abdominal cramping and experience greater loss of blood. While there is no correlation between the number of cesarean deliveries a woman has had and the likelihood of developing a CSEP, factors that impede myometrial healing (eg, preterm cesarean, cesarean after arrest of first stage of labor, chorioamnionitis) do, however, increase a patient’s risk of developing CSEP.5

Similar to tubal ectopic pregnancy, CSEP oftentimes presents early with mild, nonspecific symptoms. Thirty-nine percent of cases present with light, painless vaginal bleeding while only 25% present with abdominal pain. Moreover, 37% of cases are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis.5

One study by found the mean gestational age at diagnosis to be 7.5 weeks.5 Delayed diagnosis places the patient at risk for uterine rupture, hemorrhage, and maternal death, making suspicion and prompt diagnosis by bedside ED ultrasound essential.7,8

Regardless of one’s clinical suspicion, the diagnosis is made (or ruled out) through ultrasound. Uterine scar ectopic pregnancy is suspected when ballooning of the lower uterine segment is noted,1 when a trophoblast is seen at a presumed cesarean scar beneath the utero-vesicular fold, and when myometrium between the gestational sac and bladder wall is thin (<8 mm).2 As seen with this patient, the diagnosis is challenging as a uterine scar ectopic pregnancy can easily be mistaken for an intrauterine pregnancy. The clinician must make every effort to ensure that the pregnancy is surrounded by appropriate myometrium. It is much easier to diagnose an ectopic pregnancy far removed from the uterus, where the uterus and pregnancy are easily visualized and independent.

Management of patients with CSEP remains outside of the scope of EM, and there is no consensus among our colleagues in OB-GYN on optimal management of these patients. Options include systemic or local injection of methotrexate and potassium chloride, or minimally invasive surgery for removal.5

As bedside ultrasound by EPs becomes standard of care for first-trimester pregnancies, a greater awareness of emergent obstetric pathologies becomes necessary. Vigilance and proper ultrasound technique will enable the EP to make the diagnosis of CSEP, minimizing maternal morbidity and mortality.

Drs Haight and Watkins are residents in the division of emergency medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, Missouri. Dr Kane is a clinical instructor in the division of emergency medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, Missouri.

- Moschos E, Sreenarasimhaiah S, Twickler DM. First-trimester diagnosis of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. J Clin Ultrasound. 2008;36(8):504-511.

- Vial Y, Petignat P, Hohlfeld P. Pregnancy in a cesarean scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16(6): 592-593.

- Goldner TE, Lawson HW, Xia Z, Atrash HK. Surveillance for ectopic pregnancy—United States, 1970-1989. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1993;42(6):73-85.

- Molinaro TA, Barnhart KT. Ectopic pregnancies in unusual locations. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25(2):123-130.

- Rotas MA, Haberman S, Levgur M. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1373-1381.

- Larsen JV, Solomon MH. Pregnancy in a uterine scar sacculus—an unusual cause of postabortal haemorrhage. A case report. S Afr Med J. 1978;53(4):142-143.

- Seow KM, Huang LW, Lin YH, Lin MY, Tsai YL, Hwang JL. Caesarean scar pregnancy: issues in management. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23(3):247-253.

- Einenkel J, Stumpp P, Kösling S, Horn LC, Höckel M. A misdiagnosed case of caesarean scar pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;271(2):178-181.

Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy (CSEP) is a challenging diagnosis that warrants consideration when performing ultrasound on a pregnant patient with a previous history of cesarean delivery. It is suspected when ballooning of the lower uterine segment is noted on ultrasound,1 when a trophoblast is seen at a presumed cesarean scar beneath the utero-vesicular fold, and when myometrium between the gestational sac and bladder wall is thin (<8 mm).2

Ectopic Pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy affects approximately 2% of all pregnancies and is the leading cause of first-trimester maternal mortality.3 As front-line care providers, it is imperative that emergency physicians (EPs) recognize cases of ectopic implantation to avoid devastating outcomes.

The majority of ectopic pregnancies (97%) are located in the fallopian tubes; however, many other locations are possible, including implantation in the scar from a previous cesarean delivery.1,4 The frequency of such ectopic pregnancies is on the rise, consistent with the increasing number of cesarean deliveries performed worldwide.5 These cases present a special diagnostic challenge because patients often present asymptomatically or with painless vaginal bleeding; moreover, visualization via bedside ultrasound can be deceiving,5 and it is easy to mistake a CSEP for a viable intrauterine pregnancy.

Case

A 22-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM) presented to the ED complaining of 3 days of worsening nausea and elevated blood glucose levels. She stated that although she had been taking her insulin regimen as prescribed, her symptoms progressively worsened. On the day of presentation, she developed moderate diffuse nonradiating dull abdominal pain and had several episodes of nonbloody, nonbilious emesis. She denied being pregnant and stated that her last menstrual period was 14 days ago; she further denied any vaginal discharge or bleeding. A review of her systems was otherwise benign.

In addition to type 1 DM, the patient also had a history of migraine headaches and an obstetric history of gravida 3, para 3, aborta 0. Each birth was via cesarean delivery and without complication. Her current medications included insulin glargine (Lantus) 25 units subcutaneously every night at bedtime; insulin aspart (Novolog) 7 units subcutaneously three times a day; zolpidem (Ambien) 10 mg orally every night at bedtime. A chart review was notable for several presentations of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) secondary to noncompliance with her diabetes regimen.

Physical examination was notable for a well-developed, well-nourished 22 year old that appeared uncomfortable but in no acute distress. Her abdomen was soft and nondistended, with diffuse moderate tenderness to palpation but no rebound or guarding. The remainder of the physical

The initial workup revealed DKA and pregnancy. Significant laboratory values included: finger-stick blood glucose, 441 mg/dL; serum ketones, 2.1 mmol/L (normal range, 0.0-0.5); anion gap, 15; and urinalysis 4+ glucose, 2+ ketones; and quantitative β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG), 5,282 IU/L (normal range, 0-5.0 IU/L ).examination was otherwise benign.

After receiving insulin, intravenous (IV) fluids, pain medication, and antiemetics, the patient stated she felt much better. She was then admitted to the inpatient floor for management of DKA and discharged uneventfully several days later. Emergency bedside transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasounds were performed by the emergency staff and identified an intrauterine gestational sac and yolk sac. The EP ordered a consultation with an obstetrician-gynecologist (OB-GYN), who saw the patient in the ED and agreed with the findings, and noted the gestational sac was consistent with a date of 5 weeks, 1 day.

Six days after discharge, however, she returned to the ED complaining of several days of weakness, vomiting, and lower abdominal pain. Significant laboratory values included: urinalysis with 4+ ketones, 1+ bacteria, + nitrites; and quantitative β-HCG 25,925 IU/L (expected range, 0-5.0); serum glucose 206 mg/dL; serum ketones 0.8 (expected range, 0-0.5); and anion gap, 12.

An emergency ultrasound identified a gestational sac, yolk sac, fetal pole, and fetal heart tones; an OB-GYN ultrasound had consistent findings, with an estimated gestational age of 6 weeks, 6 days. The patient responded well to IV fluids and antiemetics, and was asymptomatic when she was admitted to the ED observation unit for continued monitoring, fluids, and antiemetics as needed. Several hours later she again began to complain of nausea, vomiting, and poorly localized abdominal discomfort. As these symptoms persisted, the OB-GYN team returned to reevaluate the patient.

Discussion

Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy was first described in the obstetric literature in 1978 and originally thought to be an exceedingly rare occurrence.5,6 With both the increasing number of cesarean deliveries performed and improvement in imaging technology, it is now believed that uterine scar ectopic pregnancy makes up as much as 6.1% of ectopic pregnancies in patients with a prior cesarean delivery.7 This diagnosis is well-documented in the obstetric and radiology literature, yet has never been discussed in an emergency medicine publication. Searching through both Pubmed and EMBase using the terms “cesarean” and “ectopic” yields no EM literature on the topic of CSEP. This is concerning because ultrasound of the pregnant patient is now a routine function of EPs.

Clinical history can be helpful in differentiating CSEP from alternative diagnoses. Patients undergoing spontaneous abortion are more likely to have lower abdominal cramping and experience greater loss of blood. While there is no correlation between the number of cesarean deliveries a woman has had and the likelihood of developing a CSEP, factors that impede myometrial healing (eg, preterm cesarean, cesarean after arrest of first stage of labor, chorioamnionitis) do, however, increase a patient’s risk of developing CSEP.5

Similar to tubal ectopic pregnancy, CSEP oftentimes presents early with mild, nonspecific symptoms. Thirty-nine percent of cases present with light, painless vaginal bleeding while only 25% present with abdominal pain. Moreover, 37% of cases are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis.5

One study by found the mean gestational age at diagnosis to be 7.5 weeks.5 Delayed diagnosis places the patient at risk for uterine rupture, hemorrhage, and maternal death, making suspicion and prompt diagnosis by bedside ED ultrasound essential.7,8

Regardless of one’s clinical suspicion, the diagnosis is made (or ruled out) through ultrasound. Uterine scar ectopic pregnancy is suspected when ballooning of the lower uterine segment is noted,1 when a trophoblast is seen at a presumed cesarean scar beneath the utero-vesicular fold, and when myometrium between the gestational sac and bladder wall is thin (<8 mm).2 As seen with this patient, the diagnosis is challenging as a uterine scar ectopic pregnancy can easily be mistaken for an intrauterine pregnancy. The clinician must make every effort to ensure that the pregnancy is surrounded by appropriate myometrium. It is much easier to diagnose an ectopic pregnancy far removed from the uterus, where the uterus and pregnancy are easily visualized and independent.

Management of patients with CSEP remains outside of the scope of EM, and there is no consensus among our colleagues in OB-GYN on optimal management of these patients. Options include systemic or local injection of methotrexate and potassium chloride, or minimally invasive surgery for removal.5

As bedside ultrasound by EPs becomes standard of care for first-trimester pregnancies, a greater awareness of emergent obstetric pathologies becomes necessary. Vigilance and proper ultrasound technique will enable the EP to make the diagnosis of CSEP, minimizing maternal morbidity and mortality.

Drs Haight and Watkins are residents in the division of emergency medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, Missouri. Dr Kane is a clinical instructor in the division of emergency medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, Missouri.

Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy (CSEP) is a challenging diagnosis that warrants consideration when performing ultrasound on a pregnant patient with a previous history of cesarean delivery. It is suspected when ballooning of the lower uterine segment is noted on ultrasound,1 when a trophoblast is seen at a presumed cesarean scar beneath the utero-vesicular fold, and when myometrium between the gestational sac and bladder wall is thin (<8 mm).2

Ectopic Pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy affects approximately 2% of all pregnancies and is the leading cause of first-trimester maternal mortality.3 As front-line care providers, it is imperative that emergency physicians (EPs) recognize cases of ectopic implantation to avoid devastating outcomes.

The majority of ectopic pregnancies (97%) are located in the fallopian tubes; however, many other locations are possible, including implantation in the scar from a previous cesarean delivery.1,4 The frequency of such ectopic pregnancies is on the rise, consistent with the increasing number of cesarean deliveries performed worldwide.5 These cases present a special diagnostic challenge because patients often present asymptomatically or with painless vaginal bleeding; moreover, visualization via bedside ultrasound can be deceiving,5 and it is easy to mistake a CSEP for a viable intrauterine pregnancy.

Case

A 22-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM) presented to the ED complaining of 3 days of worsening nausea and elevated blood glucose levels. She stated that although she had been taking her insulin regimen as prescribed, her symptoms progressively worsened. On the day of presentation, she developed moderate diffuse nonradiating dull abdominal pain and had several episodes of nonbloody, nonbilious emesis. She denied being pregnant and stated that her last menstrual period was 14 days ago; she further denied any vaginal discharge or bleeding. A review of her systems was otherwise benign.

In addition to type 1 DM, the patient also had a history of migraine headaches and an obstetric history of gravida 3, para 3, aborta 0. Each birth was via cesarean delivery and without complication. Her current medications included insulin glargine (Lantus) 25 units subcutaneously every night at bedtime; insulin aspart (Novolog) 7 units subcutaneously three times a day; zolpidem (Ambien) 10 mg orally every night at bedtime. A chart review was notable for several presentations of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) secondary to noncompliance with her diabetes regimen.

Physical examination was notable for a well-developed, well-nourished 22 year old that appeared uncomfortable but in no acute distress. Her abdomen was soft and nondistended, with diffuse moderate tenderness to palpation but no rebound or guarding. The remainder of the physical

The initial workup revealed DKA and pregnancy. Significant laboratory values included: finger-stick blood glucose, 441 mg/dL; serum ketones, 2.1 mmol/L (normal range, 0.0-0.5); anion gap, 15; and urinalysis 4+ glucose, 2+ ketones; and quantitative β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG), 5,282 IU/L (normal range, 0-5.0 IU/L ).examination was otherwise benign.

After receiving insulin, intravenous (IV) fluids, pain medication, and antiemetics, the patient stated she felt much better. She was then admitted to the inpatient floor for management of DKA and discharged uneventfully several days later. Emergency bedside transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasounds were performed by the emergency staff and identified an intrauterine gestational sac and yolk sac. The EP ordered a consultation with an obstetrician-gynecologist (OB-GYN), who saw the patient in the ED and agreed with the findings, and noted the gestational sac was consistent with a date of 5 weeks, 1 day.

Six days after discharge, however, she returned to the ED complaining of several days of weakness, vomiting, and lower abdominal pain. Significant laboratory values included: urinalysis with 4+ ketones, 1+ bacteria, + nitrites; and quantitative β-HCG 25,925 IU/L (expected range, 0-5.0); serum glucose 206 mg/dL; serum ketones 0.8 (expected range, 0-0.5); and anion gap, 12.

An emergency ultrasound identified a gestational sac, yolk sac, fetal pole, and fetal heart tones; an OB-GYN ultrasound had consistent findings, with an estimated gestational age of 6 weeks, 6 days. The patient responded well to IV fluids and antiemetics, and was asymptomatic when she was admitted to the ED observation unit for continued monitoring, fluids, and antiemetics as needed. Several hours later she again began to complain of nausea, vomiting, and poorly localized abdominal discomfort. As these symptoms persisted, the OB-GYN team returned to reevaluate the patient.

Discussion

Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy was first described in the obstetric literature in 1978 and originally thought to be an exceedingly rare occurrence.5,6 With both the increasing number of cesarean deliveries performed and improvement in imaging technology, it is now believed that uterine scar ectopic pregnancy makes up as much as 6.1% of ectopic pregnancies in patients with a prior cesarean delivery.7 This diagnosis is well-documented in the obstetric and radiology literature, yet has never been discussed in an emergency medicine publication. Searching through both Pubmed and EMBase using the terms “cesarean” and “ectopic” yields no EM literature on the topic of CSEP. This is concerning because ultrasound of the pregnant patient is now a routine function of EPs.

Clinical history can be helpful in differentiating CSEP from alternative diagnoses. Patients undergoing spontaneous abortion are more likely to have lower abdominal cramping and experience greater loss of blood. While there is no correlation between the number of cesarean deliveries a woman has had and the likelihood of developing a CSEP, factors that impede myometrial healing (eg, preterm cesarean, cesarean after arrest of first stage of labor, chorioamnionitis) do, however, increase a patient’s risk of developing CSEP.5

Similar to tubal ectopic pregnancy, CSEP oftentimes presents early with mild, nonspecific symptoms. Thirty-nine percent of cases present with light, painless vaginal bleeding while only 25% present with abdominal pain. Moreover, 37% of cases are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis.5

One study by found the mean gestational age at diagnosis to be 7.5 weeks.5 Delayed diagnosis places the patient at risk for uterine rupture, hemorrhage, and maternal death, making suspicion and prompt diagnosis by bedside ED ultrasound essential.7,8

Regardless of one’s clinical suspicion, the diagnosis is made (or ruled out) through ultrasound. Uterine scar ectopic pregnancy is suspected when ballooning of the lower uterine segment is noted,1 when a trophoblast is seen at a presumed cesarean scar beneath the utero-vesicular fold, and when myometrium between the gestational sac and bladder wall is thin (<8 mm).2 As seen with this patient, the diagnosis is challenging as a uterine scar ectopic pregnancy can easily be mistaken for an intrauterine pregnancy. The clinician must make every effort to ensure that the pregnancy is surrounded by appropriate myometrium. It is much easier to diagnose an ectopic pregnancy far removed from the uterus, where the uterus and pregnancy are easily visualized and independent.

Management of patients with CSEP remains outside of the scope of EM, and there is no consensus among our colleagues in OB-GYN on optimal management of these patients. Options include systemic or local injection of methotrexate and potassium chloride, or minimally invasive surgery for removal.5

As bedside ultrasound by EPs becomes standard of care for first-trimester pregnancies, a greater awareness of emergent obstetric pathologies becomes necessary. Vigilance and proper ultrasound technique will enable the EP to make the diagnosis of CSEP, minimizing maternal morbidity and mortality.

Drs Haight and Watkins are residents in the division of emergency medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, Missouri. Dr Kane is a clinical instructor in the division of emergency medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, Missouri.

- Moschos E, Sreenarasimhaiah S, Twickler DM. First-trimester diagnosis of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. J Clin Ultrasound. 2008;36(8):504-511.

- Vial Y, Petignat P, Hohlfeld P. Pregnancy in a cesarean scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16(6): 592-593.

- Goldner TE, Lawson HW, Xia Z, Atrash HK. Surveillance for ectopic pregnancy—United States, 1970-1989. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1993;42(6):73-85.

- Molinaro TA, Barnhart KT. Ectopic pregnancies in unusual locations. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25(2):123-130.

- Rotas MA, Haberman S, Levgur M. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1373-1381.

- Larsen JV, Solomon MH. Pregnancy in a uterine scar sacculus—an unusual cause of postabortal haemorrhage. A case report. S Afr Med J. 1978;53(4):142-143.

- Seow KM, Huang LW, Lin YH, Lin MY, Tsai YL, Hwang JL. Caesarean scar pregnancy: issues in management. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23(3):247-253.

- Einenkel J, Stumpp P, Kösling S, Horn LC, Höckel M. A misdiagnosed case of caesarean scar pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;271(2):178-181.

- Moschos E, Sreenarasimhaiah S, Twickler DM. First-trimester diagnosis of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. J Clin Ultrasound. 2008;36(8):504-511.

- Vial Y, Petignat P, Hohlfeld P. Pregnancy in a cesarean scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16(6): 592-593.

- Goldner TE, Lawson HW, Xia Z, Atrash HK. Surveillance for ectopic pregnancy—United States, 1970-1989. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1993;42(6):73-85.

- Molinaro TA, Barnhart KT. Ectopic pregnancies in unusual locations. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25(2):123-130.

- Rotas MA, Haberman S, Levgur M. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1373-1381.

- Larsen JV, Solomon MH. Pregnancy in a uterine scar sacculus—an unusual cause of postabortal haemorrhage. A case report. S Afr Med J. 1978;53(4):142-143.

- Seow KM, Huang LW, Lin YH, Lin MY, Tsai YL, Hwang JL. Caesarean scar pregnancy: issues in management. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23(3):247-253.

- Einenkel J, Stumpp P, Kösling S, Horn LC, Höckel M. A misdiagnosed case of caesarean scar pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2005;271(2):178-181.