User login

reflecting a keen interest in getting leads out of the vascular space and potentially cutting risks for infections, pneumothorax, hematoma, and the possible need for future lead extraction.

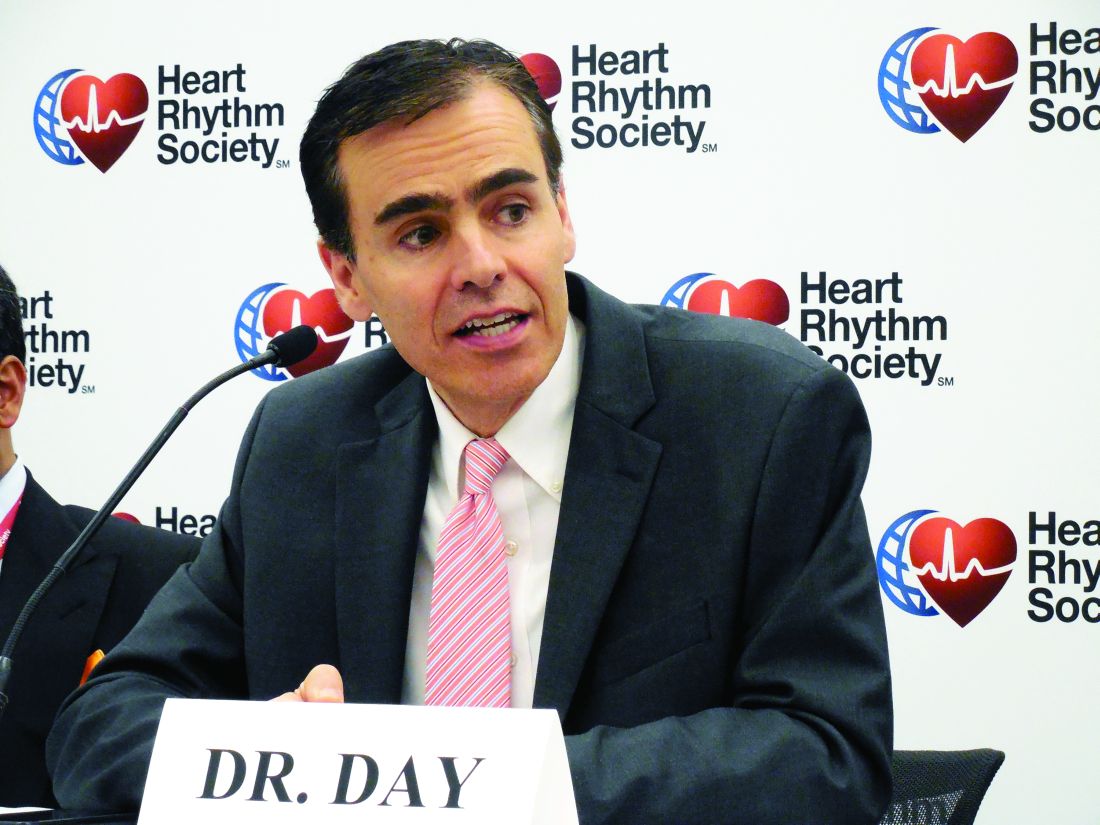

Leads are “the Achilles heel” of pacemakers and defibrillators; “there are too many places where the wire can break,” John D. Day, MD, said in an interview during the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. Eliminating transvenous leads, or any type of lead for that matter, “solves a lot of problems” that currently occur with implanted cardiac devices, said Dr. Day, a cardiac electrophysiologist with Intermountain Health in Murray, Utah.

The Acute Extravascular Defibrillation, Pacing, and Electrogram (ASD2) study tested a substernal lead in 79 patients enrolled at multiple centers in the United States and elsewhere. The lead’s design uses a minimally invasive subxiphoid approach with substernal lead advancement using a blunt tunneling rod, explained Lucas V.A. Boersma, MD, a professor of cardiology at the Academic Medical Center University in Amsterdam. Placed between the sternum and heart, the lead sits just beside the ventricles to provide both ventricular pacing and defibrillation, unlike existing subcutaneously placed leads that do not allow pacing and require high energy for defibrillation. It took a median of 12 minutes to place the lead, Dr. Boersma said.

Testing demonstrated successful ventricular pacing capture in 76 of 78 patients (97%) who underwent this testing, he reported. A single 30-joule shock delivered via the substernal lead resulted in successful defibrillation of induced fibrillation in 102 of 123 fibrillation events (83%). Six patients had seven adverse events that resolved without sequelae for all but two events. The two events with greater clinical impact included one patient with asystolic cardiac arrest 36 hours after lead placement who developed decompensated heart failure and required medical management, and one patient with pericardial effusion and tamponade who required supportive care.

“We are very used to working in the transvenous space” for lead placement, “and leaving that space is outside the comfort zone” for many clinicians, Dr. Boersma noted. “It will take time to adopt these new technologies, and obviously we need more proof” of efficacy and safety.

The second study examined a novel approach that modified the control algorithm of the Micra leadless single-chamber pacing device, approved for U.S. marketing in 2016, so that it used information collected by a built-in accelerometer to detect atrial contractions and produce atrial-ventricular (AV) synchrony in patients with AV block.

The MARVEL (Micra Atrial Tracking Using a Ventricular Accelerometer) study enrolled 70 patients at 12 centers worldwide and collected evaluable data from 64 patients. The average time spent in AV synchrony using this AV pacing was 87% in all patients, with an 80% average rate of AV synchrony in the 33 enrolled patients who had high-degree block, said Larry A. Chinitz, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Heart Rhythm Center at New York University Langone Health. Concurrently with his report at the meeting, the results also appeared in an article online (Heart Rhythm. 2018 May 11. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.05.004).

The current leadless pacemaker is very limited as a single-chamber pacing device because it can only help patients who have permanent atrial fibrillation and a slow ventricular response and hence only need single-chamber pacing, about 14% of all patients who need cardiac pacing, said Dr. Chinitz. Using the accelerometer information appears to make the Micra device suitable for the much larger number of patients who have AV block. “You effectively have dual-chamber pacing but with a single pellet. This is a simple and attractive way to do it,” Dr. Day commented. “You get a two-for-one” that potentially could triple the number of patients who could benefit from the Micra leadless device, he estimated.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SOURCE: Boersma L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-03; Chinitz L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-04.

reflecting a keen interest in getting leads out of the vascular space and potentially cutting risks for infections, pneumothorax, hematoma, and the possible need for future lead extraction.

Leads are “the Achilles heel” of pacemakers and defibrillators; “there are too many places where the wire can break,” John D. Day, MD, said in an interview during the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. Eliminating transvenous leads, or any type of lead for that matter, “solves a lot of problems” that currently occur with implanted cardiac devices, said Dr. Day, a cardiac electrophysiologist with Intermountain Health in Murray, Utah.

The Acute Extravascular Defibrillation, Pacing, and Electrogram (ASD2) study tested a substernal lead in 79 patients enrolled at multiple centers in the United States and elsewhere. The lead’s design uses a minimally invasive subxiphoid approach with substernal lead advancement using a blunt tunneling rod, explained Lucas V.A. Boersma, MD, a professor of cardiology at the Academic Medical Center University in Amsterdam. Placed between the sternum and heart, the lead sits just beside the ventricles to provide both ventricular pacing and defibrillation, unlike existing subcutaneously placed leads that do not allow pacing and require high energy for defibrillation. It took a median of 12 minutes to place the lead, Dr. Boersma said.

Testing demonstrated successful ventricular pacing capture in 76 of 78 patients (97%) who underwent this testing, he reported. A single 30-joule shock delivered via the substernal lead resulted in successful defibrillation of induced fibrillation in 102 of 123 fibrillation events (83%). Six patients had seven adverse events that resolved without sequelae for all but two events. The two events with greater clinical impact included one patient with asystolic cardiac arrest 36 hours after lead placement who developed decompensated heart failure and required medical management, and one patient with pericardial effusion and tamponade who required supportive care.

“We are very used to working in the transvenous space” for lead placement, “and leaving that space is outside the comfort zone” for many clinicians, Dr. Boersma noted. “It will take time to adopt these new technologies, and obviously we need more proof” of efficacy and safety.

The second study examined a novel approach that modified the control algorithm of the Micra leadless single-chamber pacing device, approved for U.S. marketing in 2016, so that it used information collected by a built-in accelerometer to detect atrial contractions and produce atrial-ventricular (AV) synchrony in patients with AV block.

The MARVEL (Micra Atrial Tracking Using a Ventricular Accelerometer) study enrolled 70 patients at 12 centers worldwide and collected evaluable data from 64 patients. The average time spent in AV synchrony using this AV pacing was 87% in all patients, with an 80% average rate of AV synchrony in the 33 enrolled patients who had high-degree block, said Larry A. Chinitz, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Heart Rhythm Center at New York University Langone Health. Concurrently with his report at the meeting, the results also appeared in an article online (Heart Rhythm. 2018 May 11. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.05.004).

The current leadless pacemaker is very limited as a single-chamber pacing device because it can only help patients who have permanent atrial fibrillation and a slow ventricular response and hence only need single-chamber pacing, about 14% of all patients who need cardiac pacing, said Dr. Chinitz. Using the accelerometer information appears to make the Micra device suitable for the much larger number of patients who have AV block. “You effectively have dual-chamber pacing but with a single pellet. This is a simple and attractive way to do it,” Dr. Day commented. “You get a two-for-one” that potentially could triple the number of patients who could benefit from the Micra leadless device, he estimated.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SOURCE: Boersma L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-03; Chinitz L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-04.

reflecting a keen interest in getting leads out of the vascular space and potentially cutting risks for infections, pneumothorax, hematoma, and the possible need for future lead extraction.

Leads are “the Achilles heel” of pacemakers and defibrillators; “there are too many places where the wire can break,” John D. Day, MD, said in an interview during the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. Eliminating transvenous leads, or any type of lead for that matter, “solves a lot of problems” that currently occur with implanted cardiac devices, said Dr. Day, a cardiac electrophysiologist with Intermountain Health in Murray, Utah.

The Acute Extravascular Defibrillation, Pacing, and Electrogram (ASD2) study tested a substernal lead in 79 patients enrolled at multiple centers in the United States and elsewhere. The lead’s design uses a minimally invasive subxiphoid approach with substernal lead advancement using a blunt tunneling rod, explained Lucas V.A. Boersma, MD, a professor of cardiology at the Academic Medical Center University in Amsterdam. Placed between the sternum and heart, the lead sits just beside the ventricles to provide both ventricular pacing and defibrillation, unlike existing subcutaneously placed leads that do not allow pacing and require high energy for defibrillation. It took a median of 12 minutes to place the lead, Dr. Boersma said.

Testing demonstrated successful ventricular pacing capture in 76 of 78 patients (97%) who underwent this testing, he reported. A single 30-joule shock delivered via the substernal lead resulted in successful defibrillation of induced fibrillation in 102 of 123 fibrillation events (83%). Six patients had seven adverse events that resolved without sequelae for all but two events. The two events with greater clinical impact included one patient with asystolic cardiac arrest 36 hours after lead placement who developed decompensated heart failure and required medical management, and one patient with pericardial effusion and tamponade who required supportive care.

“We are very used to working in the transvenous space” for lead placement, “and leaving that space is outside the comfort zone” for many clinicians, Dr. Boersma noted. “It will take time to adopt these new technologies, and obviously we need more proof” of efficacy and safety.

The second study examined a novel approach that modified the control algorithm of the Micra leadless single-chamber pacing device, approved for U.S. marketing in 2016, so that it used information collected by a built-in accelerometer to detect atrial contractions and produce atrial-ventricular (AV) synchrony in patients with AV block.

The MARVEL (Micra Atrial Tracking Using a Ventricular Accelerometer) study enrolled 70 patients at 12 centers worldwide and collected evaluable data from 64 patients. The average time spent in AV synchrony using this AV pacing was 87% in all patients, with an 80% average rate of AV synchrony in the 33 enrolled patients who had high-degree block, said Larry A. Chinitz, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Heart Rhythm Center at New York University Langone Health. Concurrently with his report at the meeting, the results also appeared in an article online (Heart Rhythm. 2018 May 11. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.05.004).

The current leadless pacemaker is very limited as a single-chamber pacing device because it can only help patients who have permanent atrial fibrillation and a slow ventricular response and hence only need single-chamber pacing, about 14% of all patients who need cardiac pacing, said Dr. Chinitz. Using the accelerometer information appears to make the Micra device suitable for the much larger number of patients who have AV block. “You effectively have dual-chamber pacing but with a single pellet. This is a simple and attractive way to do it,” Dr. Day commented. “You get a two-for-one” that potentially could triple the number of patients who could benefit from the Micra leadless device, he estimated.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SOURCE: Boersma L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-03; Chinitz L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-04.

REPORTING FROM HEART RHYTHM 2018

Key clinical point: Results from pilot studies showed promise for two different approaches to eliminating transvenous leads from cardiac devices.

Major finding: A substernal lead produced ventricular capture pacing in 97% of patients. Atrial syncing with an accelerometer produced AV synchrony in 87% of patients.

Study details: The ASD2 multicenter study enrolled 79 patients. The MARVEL multicenter study enrolled 64 evaluable patients.

Disclosures: The ASD2 and MARVEL studies were both funded by Medtronic, the company developing the tested devices. Dr. Boersma has been a consultant to Medtronic and Boston Scientific. Dr. Chinitz has been a consultant to Medtronic and several other device companies. Dr. Day has been a consultant to Boston Scientific, Biotronik, and St. Jude.

Source: Boersma L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-03; Chinitz L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-04.