User login

DOAC’s edge over warfarin fades with low adherence

BOSTON – The direct acting oral anticoagulants boost patient adherence compared with warfarin anticoagulation, but when patients did not adhere to their regimens, those prescribed a new, direct-acting oral anticoagulant had worse outcomes than did patients on warfarin – even patients poorly adherent with warfarin – based on data from more than 80,000 U.S. patients.

Among low-adherence patients, defined as those with adherence rates of 40%-80% based on prescriptions filled, patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2 and treated with warfarin had a 3.37/100 patient-years rate of thromboembolic events–driven hospitalizations or emergency department visits, compared with a 4.05/100 patient-years rate among low-adherence patients receiving a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC), Dhanunjaya Lakkireddy, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. The incidence of strokes of any kind was also lower in the low-adherence warfarin patients compared with the low-adherence DOAC patients, although the relationship flipped for hemorrhagic strokes and bleeds, which were more common in the warfarin patients.

In contrast, when patients were adherent, taking more than 80% of their prescribed drug, the performance of the DOACs generally surpassed that of warfarin. In an analysis adjusted for several demographic and clinical confounders, and when compared with patients adherent to a warfarin regimen, those adherent to a DOAC had a 7% lower rate of thromboembolic events, a 36% lower rate of hemorrhagic strokes, an 8% lower rate of any stroke, and a 10% lower rate of bleeds (excluding hemorrhagic strokes), all statistically significant differences, reported Dr. Lakkireddy, medical director of the Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute in Overland Park, Kan.

The message from this analysis is the importance of maximizing patient adherence, Dr. Lakkireddy said.

“We should not make the false assumption that putting a patient on a DOAC will take care of everything. We need to make it a habit to make sure patients are taking their pills,” he said in an interview. “We were surprised. Our assumption was that the DOACs were more forgiving than warfarin” in poorly compliant patients. “We need to make talking about adherence with patients routine.”

The results also documented that adherence to therapy is better with a DOAC, with a 74% rate of good adherence among the nearly 41,000 patients in the database prescribed a DOAC compared with a 63% rate of good compliance among the more than 42,000 patients prescribed warfarin.

“It’s ironic that we might think low-adherence patients should go on warfarin. That’s sort of backwards,” said Andrew D. Krahn, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist and professor of medicine at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. “It’s not biologically plausible” to predict that less adherent patients would do better on warfarin, he noted.

The study run by Dr. Lakkireddy and his associates used data collected by IBM Watson Health Market Scan from about 4 million Medicare patients and 47 million American residents with private insurance during 2012-2016. They focused on the more than 600,000 patients prescribed an anticoagulant during 2014 and 2015, and then narrowed the study group down to just over 83,000 adults with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more. The patients’ average age was about 74 years.

Dr. Lakkireddy has been a consultant to or has received research support from Biosense Webster, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, EstechPharma, Janssen, Pfizer, SentreHeart, and St. Jude. Dr. Krahn has been a consultant to Medtronic and has received research support from Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

SOURCE: Lakkireddy D et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT02-03.

What is clear from this analysis is that adherence to oral anticoagulant regimens is something we need to address. It would help if we could determine why patients are not well adherent, but regardless of the cause, changing patient behavior and improving adherence will require better patient education and better integration of medical care toward better adherence.

This study has several obvious limitations, including its reliance on an administrative database that does not allow for adjudication of outcomes. The analysis presented so far is also limited by not breaking down the direct-acting oral anticoagulant into individual drugs, and without propensity-score matching of the two treatment subgroups.

We must be very alert to the possibility for confounding by indication in a real-world dataset like this. For example, the stroke rate we see in the patients treated with a DOAC may be affected by clinicians who preferentially prescribed one of the direct-acting drugs to patients who had what they thought was a high stroke risk because they felt these drugs might work better for stroke prevention than warfarin.

What is also notable in the results is that, even among the patients with good adherence, the event and adverse effects rates remained high. Among the highly adherent patients the thromboembolic event rate was greater than 3% per year in both the warfarin and direct-acting drug groups, the stroke rate was also greater than 3% per year in both subgroups, and bleeding events occurred at rates of greater than 4% per year among the patients treated with direct-acting drugs and greater than 5% per year in the warfarin group.

Hein Heidbuchel, MD, professor of medicine and chair of cardiology at the University of Antwerp, Belgium, made these comments as designated discussant for the study. He had no current disclosures.

What is clear from this analysis is that adherence to oral anticoagulant regimens is something we need to address. It would help if we could determine why patients are not well adherent, but regardless of the cause, changing patient behavior and improving adherence will require better patient education and better integration of medical care toward better adherence.

This study has several obvious limitations, including its reliance on an administrative database that does not allow for adjudication of outcomes. The analysis presented so far is also limited by not breaking down the direct-acting oral anticoagulant into individual drugs, and without propensity-score matching of the two treatment subgroups.

We must be very alert to the possibility for confounding by indication in a real-world dataset like this. For example, the stroke rate we see in the patients treated with a DOAC may be affected by clinicians who preferentially prescribed one of the direct-acting drugs to patients who had what they thought was a high stroke risk because they felt these drugs might work better for stroke prevention than warfarin.

What is also notable in the results is that, even among the patients with good adherence, the event and adverse effects rates remained high. Among the highly adherent patients the thromboembolic event rate was greater than 3% per year in both the warfarin and direct-acting drug groups, the stroke rate was also greater than 3% per year in both subgroups, and bleeding events occurred at rates of greater than 4% per year among the patients treated with direct-acting drugs and greater than 5% per year in the warfarin group.

Hein Heidbuchel, MD, professor of medicine and chair of cardiology at the University of Antwerp, Belgium, made these comments as designated discussant for the study. He had no current disclosures.

What is clear from this analysis is that adherence to oral anticoagulant regimens is something we need to address. It would help if we could determine why patients are not well adherent, but regardless of the cause, changing patient behavior and improving adherence will require better patient education and better integration of medical care toward better adherence.

This study has several obvious limitations, including its reliance on an administrative database that does not allow for adjudication of outcomes. The analysis presented so far is also limited by not breaking down the direct-acting oral anticoagulant into individual drugs, and without propensity-score matching of the two treatment subgroups.

We must be very alert to the possibility for confounding by indication in a real-world dataset like this. For example, the stroke rate we see in the patients treated with a DOAC may be affected by clinicians who preferentially prescribed one of the direct-acting drugs to patients who had what they thought was a high stroke risk because they felt these drugs might work better for stroke prevention than warfarin.

What is also notable in the results is that, even among the patients with good adherence, the event and adverse effects rates remained high. Among the highly adherent patients the thromboembolic event rate was greater than 3% per year in both the warfarin and direct-acting drug groups, the stroke rate was also greater than 3% per year in both subgroups, and bleeding events occurred at rates of greater than 4% per year among the patients treated with direct-acting drugs and greater than 5% per year in the warfarin group.

Hein Heidbuchel, MD, professor of medicine and chair of cardiology at the University of Antwerp, Belgium, made these comments as designated discussant for the study. He had no current disclosures.

BOSTON – The direct acting oral anticoagulants boost patient adherence compared with warfarin anticoagulation, but when patients did not adhere to their regimens, those prescribed a new, direct-acting oral anticoagulant had worse outcomes than did patients on warfarin – even patients poorly adherent with warfarin – based on data from more than 80,000 U.S. patients.

Among low-adherence patients, defined as those with adherence rates of 40%-80% based on prescriptions filled, patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2 and treated with warfarin had a 3.37/100 patient-years rate of thromboembolic events–driven hospitalizations or emergency department visits, compared with a 4.05/100 patient-years rate among low-adherence patients receiving a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC), Dhanunjaya Lakkireddy, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. The incidence of strokes of any kind was also lower in the low-adherence warfarin patients compared with the low-adherence DOAC patients, although the relationship flipped for hemorrhagic strokes and bleeds, which were more common in the warfarin patients.

In contrast, when patients were adherent, taking more than 80% of their prescribed drug, the performance of the DOACs generally surpassed that of warfarin. In an analysis adjusted for several demographic and clinical confounders, and when compared with patients adherent to a warfarin regimen, those adherent to a DOAC had a 7% lower rate of thromboembolic events, a 36% lower rate of hemorrhagic strokes, an 8% lower rate of any stroke, and a 10% lower rate of bleeds (excluding hemorrhagic strokes), all statistically significant differences, reported Dr. Lakkireddy, medical director of the Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute in Overland Park, Kan.

The message from this analysis is the importance of maximizing patient adherence, Dr. Lakkireddy said.

“We should not make the false assumption that putting a patient on a DOAC will take care of everything. We need to make it a habit to make sure patients are taking their pills,” he said in an interview. “We were surprised. Our assumption was that the DOACs were more forgiving than warfarin” in poorly compliant patients. “We need to make talking about adherence with patients routine.”

The results also documented that adherence to therapy is better with a DOAC, with a 74% rate of good adherence among the nearly 41,000 patients in the database prescribed a DOAC compared with a 63% rate of good compliance among the more than 42,000 patients prescribed warfarin.

“It’s ironic that we might think low-adherence patients should go on warfarin. That’s sort of backwards,” said Andrew D. Krahn, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist and professor of medicine at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. “It’s not biologically plausible” to predict that less adherent patients would do better on warfarin, he noted.

The study run by Dr. Lakkireddy and his associates used data collected by IBM Watson Health Market Scan from about 4 million Medicare patients and 47 million American residents with private insurance during 2012-2016. They focused on the more than 600,000 patients prescribed an anticoagulant during 2014 and 2015, and then narrowed the study group down to just over 83,000 adults with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more. The patients’ average age was about 74 years.

Dr. Lakkireddy has been a consultant to or has received research support from Biosense Webster, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, EstechPharma, Janssen, Pfizer, SentreHeart, and St. Jude. Dr. Krahn has been a consultant to Medtronic and has received research support from Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

SOURCE: Lakkireddy D et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT02-03.

BOSTON – The direct acting oral anticoagulants boost patient adherence compared with warfarin anticoagulation, but when patients did not adhere to their regimens, those prescribed a new, direct-acting oral anticoagulant had worse outcomes than did patients on warfarin – even patients poorly adherent with warfarin – based on data from more than 80,000 U.S. patients.

Among low-adherence patients, defined as those with adherence rates of 40%-80% based on prescriptions filled, patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2 and treated with warfarin had a 3.37/100 patient-years rate of thromboembolic events–driven hospitalizations or emergency department visits, compared with a 4.05/100 patient-years rate among low-adherence patients receiving a direct-acting oral anticoagulant (DOAC), Dhanunjaya Lakkireddy, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. The incidence of strokes of any kind was also lower in the low-adherence warfarin patients compared with the low-adherence DOAC patients, although the relationship flipped for hemorrhagic strokes and bleeds, which were more common in the warfarin patients.

In contrast, when patients were adherent, taking more than 80% of their prescribed drug, the performance of the DOACs generally surpassed that of warfarin. In an analysis adjusted for several demographic and clinical confounders, and when compared with patients adherent to a warfarin regimen, those adherent to a DOAC had a 7% lower rate of thromboembolic events, a 36% lower rate of hemorrhagic strokes, an 8% lower rate of any stroke, and a 10% lower rate of bleeds (excluding hemorrhagic strokes), all statistically significant differences, reported Dr. Lakkireddy, medical director of the Kansas City Heart Rhythm Institute in Overland Park, Kan.

The message from this analysis is the importance of maximizing patient adherence, Dr. Lakkireddy said.

“We should not make the false assumption that putting a patient on a DOAC will take care of everything. We need to make it a habit to make sure patients are taking their pills,” he said in an interview. “We were surprised. Our assumption was that the DOACs were more forgiving than warfarin” in poorly compliant patients. “We need to make talking about adherence with patients routine.”

The results also documented that adherence to therapy is better with a DOAC, with a 74% rate of good adherence among the nearly 41,000 patients in the database prescribed a DOAC compared with a 63% rate of good compliance among the more than 42,000 patients prescribed warfarin.

“It’s ironic that we might think low-adherence patients should go on warfarin. That’s sort of backwards,” said Andrew D. Krahn, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist and professor of medicine at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. “It’s not biologically plausible” to predict that less adherent patients would do better on warfarin, he noted.

The study run by Dr. Lakkireddy and his associates used data collected by IBM Watson Health Market Scan from about 4 million Medicare patients and 47 million American residents with private insurance during 2012-2016. They focused on the more than 600,000 patients prescribed an anticoagulant during 2014 and 2015, and then narrowed the study group down to just over 83,000 adults with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more. The patients’ average age was about 74 years.

Dr. Lakkireddy has been a consultant to or has received research support from Biosense Webster, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, EstechPharma, Janssen, Pfizer, SentreHeart, and St. Jude. Dr. Krahn has been a consultant to Medtronic and has received research support from Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

SOURCE: Lakkireddy D et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT02-03.

REPORTING FROM HEART RHYTHM 2018

Key clinical point: Good adherence is needed for direct-acting oral anticoagulants to outperform warfarin.

Major finding: Thromboembolic events in low-adherence patients were 4.05/100 patient years with a DOAC and 3.37/100 patient years with warfarin.

Study details: Analysis of 83,168 insured U.S. atrial fibrillation patients treated with an oral anticoagulant in 2014-2015.

Disclosures: Dr. Lakkireddy has been a consultant to or has received research support from Biosense Webster, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, EstechPharma, Janssen, Pfizer, SentreHeart, and St. Jude. Dr. Krahn has been a consultant to Medtronic and has received research support from Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

Source: Lakkireddy D et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT02-03.

New strategies eliminate cardiac device transvenous leads

reflecting a keen interest in getting leads out of the vascular space and potentially cutting risks for infections, pneumothorax, hematoma, and the possible need for future lead extraction.

Leads are “the Achilles heel” of pacemakers and defibrillators; “there are too many places where the wire can break,” John D. Day, MD, said in an interview during the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. Eliminating transvenous leads, or any type of lead for that matter, “solves a lot of problems” that currently occur with implanted cardiac devices, said Dr. Day, a cardiac electrophysiologist with Intermountain Health in Murray, Utah.

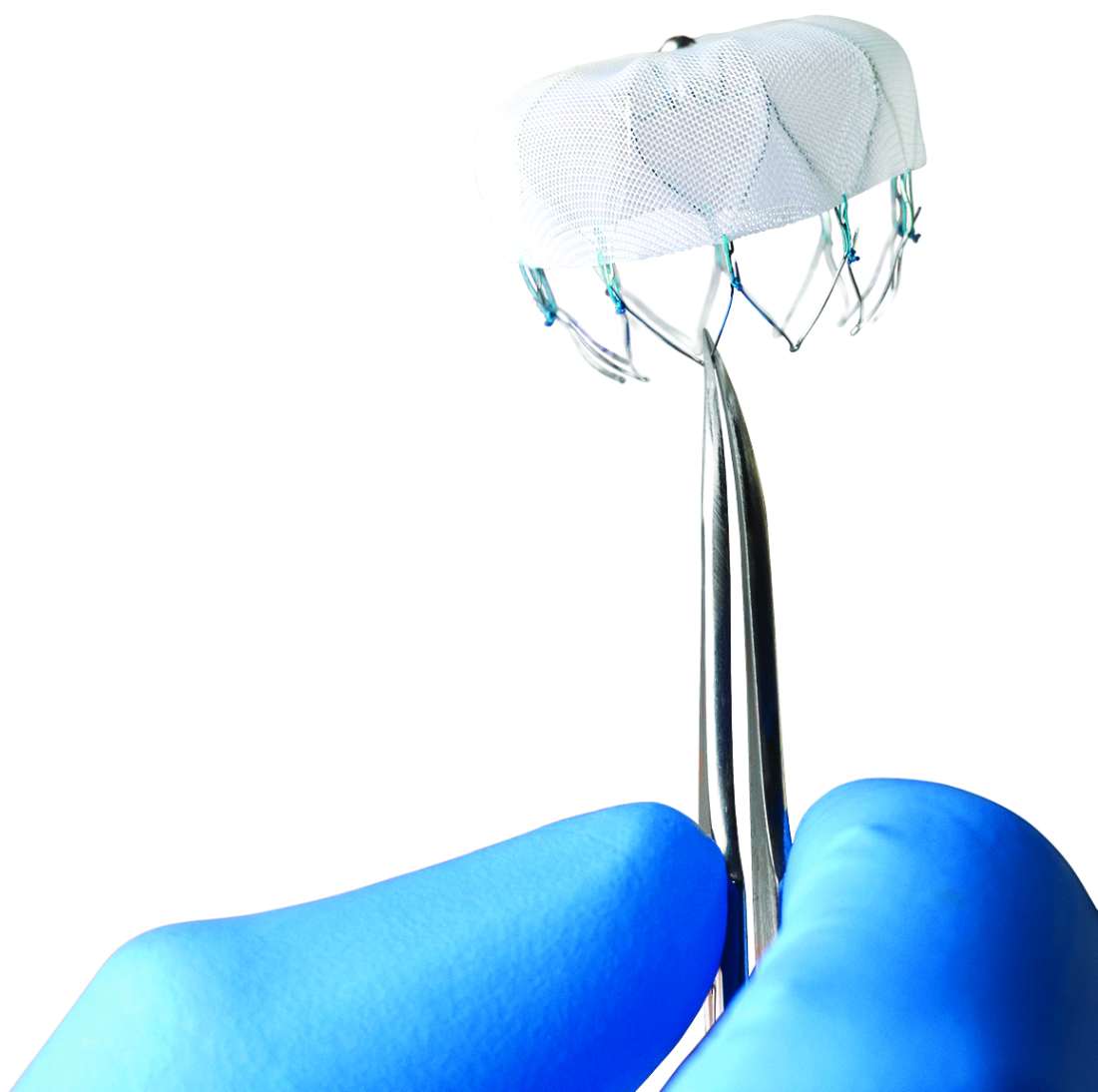

The Acute Extravascular Defibrillation, Pacing, and Electrogram (ASD2) study tested a substernal lead in 79 patients enrolled at multiple centers in the United States and elsewhere. The lead’s design uses a minimally invasive subxiphoid approach with substernal lead advancement using a blunt tunneling rod, explained Lucas V.A. Boersma, MD, a professor of cardiology at the Academic Medical Center University in Amsterdam. Placed between the sternum and heart, the lead sits just beside the ventricles to provide both ventricular pacing and defibrillation, unlike existing subcutaneously placed leads that do not allow pacing and require high energy for defibrillation. It took a median of 12 minutes to place the lead, Dr. Boersma said.

Testing demonstrated successful ventricular pacing capture in 76 of 78 patients (97%) who underwent this testing, he reported. A single 30-joule shock delivered via the substernal lead resulted in successful defibrillation of induced fibrillation in 102 of 123 fibrillation events (83%). Six patients had seven adverse events that resolved without sequelae for all but two events. The two events with greater clinical impact included one patient with asystolic cardiac arrest 36 hours after lead placement who developed decompensated heart failure and required medical management, and one patient with pericardial effusion and tamponade who required supportive care.

“We are very used to working in the transvenous space” for lead placement, “and leaving that space is outside the comfort zone” for many clinicians, Dr. Boersma noted. “It will take time to adopt these new technologies, and obviously we need more proof” of efficacy and safety.

The second study examined a novel approach that modified the control algorithm of the Micra leadless single-chamber pacing device, approved for U.S. marketing in 2016, so that it used information collected by a built-in accelerometer to detect atrial contractions and produce atrial-ventricular (AV) synchrony in patients with AV block.

The MARVEL (Micra Atrial Tracking Using a Ventricular Accelerometer) study enrolled 70 patients at 12 centers worldwide and collected evaluable data from 64 patients. The average time spent in AV synchrony using this AV pacing was 87% in all patients, with an 80% average rate of AV synchrony in the 33 enrolled patients who had high-degree block, said Larry A. Chinitz, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Heart Rhythm Center at New York University Langone Health. Concurrently with his report at the meeting, the results also appeared in an article online (Heart Rhythm. 2018 May 11. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.05.004).

The current leadless pacemaker is very limited as a single-chamber pacing device because it can only help patients who have permanent atrial fibrillation and a slow ventricular response and hence only need single-chamber pacing, about 14% of all patients who need cardiac pacing, said Dr. Chinitz. Using the accelerometer information appears to make the Micra device suitable for the much larger number of patients who have AV block. “You effectively have dual-chamber pacing but with a single pellet. This is a simple and attractive way to do it,” Dr. Day commented. “You get a two-for-one” that potentially could triple the number of patients who could benefit from the Micra leadless device, he estimated.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SOURCE: Boersma L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-03; Chinitz L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-04.

reflecting a keen interest in getting leads out of the vascular space and potentially cutting risks for infections, pneumothorax, hematoma, and the possible need for future lead extraction.

Leads are “the Achilles heel” of pacemakers and defibrillators; “there are too many places where the wire can break,” John D. Day, MD, said in an interview during the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. Eliminating transvenous leads, or any type of lead for that matter, “solves a lot of problems” that currently occur with implanted cardiac devices, said Dr. Day, a cardiac electrophysiologist with Intermountain Health in Murray, Utah.

The Acute Extravascular Defibrillation, Pacing, and Electrogram (ASD2) study tested a substernal lead in 79 patients enrolled at multiple centers in the United States and elsewhere. The lead’s design uses a minimally invasive subxiphoid approach with substernal lead advancement using a blunt tunneling rod, explained Lucas V.A. Boersma, MD, a professor of cardiology at the Academic Medical Center University in Amsterdam. Placed between the sternum and heart, the lead sits just beside the ventricles to provide both ventricular pacing and defibrillation, unlike existing subcutaneously placed leads that do not allow pacing and require high energy for defibrillation. It took a median of 12 minutes to place the lead, Dr. Boersma said.

Testing demonstrated successful ventricular pacing capture in 76 of 78 patients (97%) who underwent this testing, he reported. A single 30-joule shock delivered via the substernal lead resulted in successful defibrillation of induced fibrillation in 102 of 123 fibrillation events (83%). Six patients had seven adverse events that resolved without sequelae for all but two events. The two events with greater clinical impact included one patient with asystolic cardiac arrest 36 hours after lead placement who developed decompensated heart failure and required medical management, and one patient with pericardial effusion and tamponade who required supportive care.

“We are very used to working in the transvenous space” for lead placement, “and leaving that space is outside the comfort zone” for many clinicians, Dr. Boersma noted. “It will take time to adopt these new technologies, and obviously we need more proof” of efficacy and safety.

The second study examined a novel approach that modified the control algorithm of the Micra leadless single-chamber pacing device, approved for U.S. marketing in 2016, so that it used information collected by a built-in accelerometer to detect atrial contractions and produce atrial-ventricular (AV) synchrony in patients with AV block.

The MARVEL (Micra Atrial Tracking Using a Ventricular Accelerometer) study enrolled 70 patients at 12 centers worldwide and collected evaluable data from 64 patients. The average time spent in AV synchrony using this AV pacing was 87% in all patients, with an 80% average rate of AV synchrony in the 33 enrolled patients who had high-degree block, said Larry A. Chinitz, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Heart Rhythm Center at New York University Langone Health. Concurrently with his report at the meeting, the results also appeared in an article online (Heart Rhythm. 2018 May 11. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.05.004).

The current leadless pacemaker is very limited as a single-chamber pacing device because it can only help patients who have permanent atrial fibrillation and a slow ventricular response and hence only need single-chamber pacing, about 14% of all patients who need cardiac pacing, said Dr. Chinitz. Using the accelerometer information appears to make the Micra device suitable for the much larger number of patients who have AV block. “You effectively have dual-chamber pacing but with a single pellet. This is a simple and attractive way to do it,” Dr. Day commented. “You get a two-for-one” that potentially could triple the number of patients who could benefit from the Micra leadless device, he estimated.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SOURCE: Boersma L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-03; Chinitz L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-04.

reflecting a keen interest in getting leads out of the vascular space and potentially cutting risks for infections, pneumothorax, hematoma, and the possible need for future lead extraction.

Leads are “the Achilles heel” of pacemakers and defibrillators; “there are too many places where the wire can break,” John D. Day, MD, said in an interview during the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. Eliminating transvenous leads, or any type of lead for that matter, “solves a lot of problems” that currently occur with implanted cardiac devices, said Dr. Day, a cardiac electrophysiologist with Intermountain Health in Murray, Utah.

The Acute Extravascular Defibrillation, Pacing, and Electrogram (ASD2) study tested a substernal lead in 79 patients enrolled at multiple centers in the United States and elsewhere. The lead’s design uses a minimally invasive subxiphoid approach with substernal lead advancement using a blunt tunneling rod, explained Lucas V.A. Boersma, MD, a professor of cardiology at the Academic Medical Center University in Amsterdam. Placed between the sternum and heart, the lead sits just beside the ventricles to provide both ventricular pacing and defibrillation, unlike existing subcutaneously placed leads that do not allow pacing and require high energy for defibrillation. It took a median of 12 minutes to place the lead, Dr. Boersma said.

Testing demonstrated successful ventricular pacing capture in 76 of 78 patients (97%) who underwent this testing, he reported. A single 30-joule shock delivered via the substernal lead resulted in successful defibrillation of induced fibrillation in 102 of 123 fibrillation events (83%). Six patients had seven adverse events that resolved without sequelae for all but two events. The two events with greater clinical impact included one patient with asystolic cardiac arrest 36 hours after lead placement who developed decompensated heart failure and required medical management, and one patient with pericardial effusion and tamponade who required supportive care.

“We are very used to working in the transvenous space” for lead placement, “and leaving that space is outside the comfort zone” for many clinicians, Dr. Boersma noted. “It will take time to adopt these new technologies, and obviously we need more proof” of efficacy and safety.

The second study examined a novel approach that modified the control algorithm of the Micra leadless single-chamber pacing device, approved for U.S. marketing in 2016, so that it used information collected by a built-in accelerometer to detect atrial contractions and produce atrial-ventricular (AV) synchrony in patients with AV block.

The MARVEL (Micra Atrial Tracking Using a Ventricular Accelerometer) study enrolled 70 patients at 12 centers worldwide and collected evaluable data from 64 patients. The average time spent in AV synchrony using this AV pacing was 87% in all patients, with an 80% average rate of AV synchrony in the 33 enrolled patients who had high-degree block, said Larry A. Chinitz, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Heart Rhythm Center at New York University Langone Health. Concurrently with his report at the meeting, the results also appeared in an article online (Heart Rhythm. 2018 May 11. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.05.004).

The current leadless pacemaker is very limited as a single-chamber pacing device because it can only help patients who have permanent atrial fibrillation and a slow ventricular response and hence only need single-chamber pacing, about 14% of all patients who need cardiac pacing, said Dr. Chinitz. Using the accelerometer information appears to make the Micra device suitable for the much larger number of patients who have AV block. “You effectively have dual-chamber pacing but with a single pellet. This is a simple and attractive way to do it,” Dr. Day commented. “You get a two-for-one” that potentially could triple the number of patients who could benefit from the Micra leadless device, he estimated.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

SOURCE: Boersma L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-03; Chinitz L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-04.

REPORTING FROM HEART RHYTHM 2018

Key clinical point: Results from pilot studies showed promise for two different approaches to eliminating transvenous leads from cardiac devices.

Major finding: A substernal lead produced ventricular capture pacing in 97% of patients. Atrial syncing with an accelerometer produced AV synchrony in 87% of patients.

Study details: The ASD2 multicenter study enrolled 79 patients. The MARVEL multicenter study enrolled 64 evaluable patients.

Disclosures: The ASD2 and MARVEL studies were both funded by Medtronic, the company developing the tested devices. Dr. Boersma has been a consultant to Medtronic and Boston Scientific. Dr. Chinitz has been a consultant to Medtronic and several other device companies. Dr. Day has been a consultant to Boston Scientific, Biotronik, and St. Jude.

Source: Boersma L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-03; Chinitz L et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT03-04.

Myocarditis shows causal role in frequent PVCs

BOSTON – About half of patients who present with a new onset of frequent premature ventricular contractions without obvious underlying heart disease had an underlying myocardial inflammation that was often responsive to immunosuppressive treatment, according to a single-center series of 107 patients.

“Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment with immunosuppressive therapy can significantly affect the clinical course,” although large-scale, multicenter, randomized trials must confirm this as an effective management approach, Dhanunjaya Lakkireddy, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. He stressed that the anecdotal efficacy seen in this series with immunosuppressive therapy and selected use of ablation treatment for the premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) applies only to patients with new-onset PVCs that occur at a rate of at least 5,000 during 24 hours who also have myocardial inflammation identified by a PET scan showing increased fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake.

The apparent impact of immunosuppressive treatment was “profound,” Dr. Lakkireddy said. The treatment usually involved prednisone and, in many patients, a second immunosuppressant agent such as azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, or methotrexate. The results suggest “a unique opportunity to intervene early with immunosuppression to change the natural course of the disease. PVCs may be the earliest sign of a disease process” featuring myocardial inflammation.

The data came from the Myocarditis and Ventricular Arrhythmia (MAVERIC) registry that Dr. Lakkireddy and his associates started because “we began seeing patients referred for ablations without underlying heart disease who had suddenly presented with a lot of PVCs,” he recalled, an observation that led them to systematically study these patients in an “arduous” process that involved several tests. One hundred seven patients met the registry’s inclusion criteria for new onset of frequent PVCs without apparent underlying heart disease, and roughly half of these patients showed clear evidence of myocardial inflammation by FDG and PET imaging. “If the PET is negative, I don’t worry about myocarditis, “ Dr. Lakkireddy said.

The 55 patients with apparent myocarditis on PET imaging, out of the 107 patients examined generally, had lower left ventricular (LV) ejection fractions averaging 46%, compared with 51% among the patients without myocarditis The patients with myocarditis further subdivided into 27 with preserved LV function, with an average ejection fraction of 60%, and 28 with a reduced LV function, with an average ejection fraction of 40%. The researchers saw an optimal response to immunosuppressive therapy in 18 of the 23 patients (78%) with preserved ejection fractions who received this treatment and in 13 of the 24 patients (54%) with diminished LV ejection fractions who got immunosuppressive therapy.

Twenty-eight of the 55 patients with myocarditis on PET imaging underwent a right-sided biopsy during their work-up, and 13 of these 28 biopsies (46%) showed a lymphocytic infiltrate of a type often seen in patients with postviral myocarditis. Seven of the 28 biopsied patients (25%) had completely normal-appearing cardiac tissue.

Dr. Lakkireddy has been a consultant to or has received research support from Biosense Webster, Boehinger Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Estech, Janssen, Pfizer, SentreHeart, and St. Jude.

SOURCE: Lakkireddy D et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT02-02.

I was quite taken by this study, which produced results that raise shock and alarm. I believe that the clinical condition that this study highlights is a real biological phenomenon that affects patients who were not on my radar screen.

From now on, I will certainly be more alert for and concerned about patients whom I see with an abrupt onset of frequent premature ventricular contractions, especially those who also have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. However the potential need to use serial PET examinations to identify and then follow these patients also raises concern about the cumulative radiation exposure patients could receive from serial PET studies.

David J. Callans, MD , is professor of medicine and associate director of electrophysiology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He has been a consultant to Abbott, Biosense Webster, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude. He made these comments as designated discussant for the report.

I was quite taken by this study, which produced results that raise shock and alarm. I believe that the clinical condition that this study highlights is a real biological phenomenon that affects patients who were not on my radar screen.

From now on, I will certainly be more alert for and concerned about patients whom I see with an abrupt onset of frequent premature ventricular contractions, especially those who also have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. However the potential need to use serial PET examinations to identify and then follow these patients also raises concern about the cumulative radiation exposure patients could receive from serial PET studies.

David J. Callans, MD , is professor of medicine and associate director of electrophysiology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He has been a consultant to Abbott, Biosense Webster, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude. He made these comments as designated discussant for the report.

I was quite taken by this study, which produced results that raise shock and alarm. I believe that the clinical condition that this study highlights is a real biological phenomenon that affects patients who were not on my radar screen.

From now on, I will certainly be more alert for and concerned about patients whom I see with an abrupt onset of frequent premature ventricular contractions, especially those who also have a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. However the potential need to use serial PET examinations to identify and then follow these patients also raises concern about the cumulative radiation exposure patients could receive from serial PET studies.

David J. Callans, MD , is professor of medicine and associate director of electrophysiology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He has been a consultant to Abbott, Biosense Webster, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude. He made these comments as designated discussant for the report.

BOSTON – About half of patients who present with a new onset of frequent premature ventricular contractions without obvious underlying heart disease had an underlying myocardial inflammation that was often responsive to immunosuppressive treatment, according to a single-center series of 107 patients.

“Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment with immunosuppressive therapy can significantly affect the clinical course,” although large-scale, multicenter, randomized trials must confirm this as an effective management approach, Dhanunjaya Lakkireddy, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. He stressed that the anecdotal efficacy seen in this series with immunosuppressive therapy and selected use of ablation treatment for the premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) applies only to patients with new-onset PVCs that occur at a rate of at least 5,000 during 24 hours who also have myocardial inflammation identified by a PET scan showing increased fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake.

The apparent impact of immunosuppressive treatment was “profound,” Dr. Lakkireddy said. The treatment usually involved prednisone and, in many patients, a second immunosuppressant agent such as azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, or methotrexate. The results suggest “a unique opportunity to intervene early with immunosuppression to change the natural course of the disease. PVCs may be the earliest sign of a disease process” featuring myocardial inflammation.

The data came from the Myocarditis and Ventricular Arrhythmia (MAVERIC) registry that Dr. Lakkireddy and his associates started because “we began seeing patients referred for ablations without underlying heart disease who had suddenly presented with a lot of PVCs,” he recalled, an observation that led them to systematically study these patients in an “arduous” process that involved several tests. One hundred seven patients met the registry’s inclusion criteria for new onset of frequent PVCs without apparent underlying heart disease, and roughly half of these patients showed clear evidence of myocardial inflammation by FDG and PET imaging. “If the PET is negative, I don’t worry about myocarditis, “ Dr. Lakkireddy said.

The 55 patients with apparent myocarditis on PET imaging, out of the 107 patients examined generally, had lower left ventricular (LV) ejection fractions averaging 46%, compared with 51% among the patients without myocarditis The patients with myocarditis further subdivided into 27 with preserved LV function, with an average ejection fraction of 60%, and 28 with a reduced LV function, with an average ejection fraction of 40%. The researchers saw an optimal response to immunosuppressive therapy in 18 of the 23 patients (78%) with preserved ejection fractions who received this treatment and in 13 of the 24 patients (54%) with diminished LV ejection fractions who got immunosuppressive therapy.

Twenty-eight of the 55 patients with myocarditis on PET imaging underwent a right-sided biopsy during their work-up, and 13 of these 28 biopsies (46%) showed a lymphocytic infiltrate of a type often seen in patients with postviral myocarditis. Seven of the 28 biopsied patients (25%) had completely normal-appearing cardiac tissue.

Dr. Lakkireddy has been a consultant to or has received research support from Biosense Webster, Boehinger Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Estech, Janssen, Pfizer, SentreHeart, and St. Jude.

SOURCE: Lakkireddy D et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT02-02.

BOSTON – About half of patients who present with a new onset of frequent premature ventricular contractions without obvious underlying heart disease had an underlying myocardial inflammation that was often responsive to immunosuppressive treatment, according to a single-center series of 107 patients.

“Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment with immunosuppressive therapy can significantly affect the clinical course,” although large-scale, multicenter, randomized trials must confirm this as an effective management approach, Dhanunjaya Lakkireddy, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. He stressed that the anecdotal efficacy seen in this series with immunosuppressive therapy and selected use of ablation treatment for the premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) applies only to patients with new-onset PVCs that occur at a rate of at least 5,000 during 24 hours who also have myocardial inflammation identified by a PET scan showing increased fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake.

The apparent impact of immunosuppressive treatment was “profound,” Dr. Lakkireddy said. The treatment usually involved prednisone and, in many patients, a second immunosuppressant agent such as azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, or methotrexate. The results suggest “a unique opportunity to intervene early with immunosuppression to change the natural course of the disease. PVCs may be the earliest sign of a disease process” featuring myocardial inflammation.

The data came from the Myocarditis and Ventricular Arrhythmia (MAVERIC) registry that Dr. Lakkireddy and his associates started because “we began seeing patients referred for ablations without underlying heart disease who had suddenly presented with a lot of PVCs,” he recalled, an observation that led them to systematically study these patients in an “arduous” process that involved several tests. One hundred seven patients met the registry’s inclusion criteria for new onset of frequent PVCs without apparent underlying heart disease, and roughly half of these patients showed clear evidence of myocardial inflammation by FDG and PET imaging. “If the PET is negative, I don’t worry about myocarditis, “ Dr. Lakkireddy said.

The 55 patients with apparent myocarditis on PET imaging, out of the 107 patients examined generally, had lower left ventricular (LV) ejection fractions averaging 46%, compared with 51% among the patients without myocarditis The patients with myocarditis further subdivided into 27 with preserved LV function, with an average ejection fraction of 60%, and 28 with a reduced LV function, with an average ejection fraction of 40%. The researchers saw an optimal response to immunosuppressive therapy in 18 of the 23 patients (78%) with preserved ejection fractions who received this treatment and in 13 of the 24 patients (54%) with diminished LV ejection fractions who got immunosuppressive therapy.

Twenty-eight of the 55 patients with myocarditis on PET imaging underwent a right-sided biopsy during their work-up, and 13 of these 28 biopsies (46%) showed a lymphocytic infiltrate of a type often seen in patients with postviral myocarditis. Seven of the 28 biopsied patients (25%) had completely normal-appearing cardiac tissue.

Dr. Lakkireddy has been a consultant to or has received research support from Biosense Webster, Boehinger Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Estech, Janssen, Pfizer, SentreHeart, and St. Jude.

SOURCE: Lakkireddy D et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT02-02.

REPORTING FROM HEART RHYTHM 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Immunosuppressive therapy resolved myocarditis in two-thirds of 51% of patients with new-onset, frequents PVCs.

Study details: Single-center series with 107 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Lakkireddy has been a consultant to or has received research support from Biosense Webster, Boehinger Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Estech, Janssen, Pfizer, SentreHeart, and St. Jude.

Source: Lakkireddy D et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT02-02.

Single Botox treatment cuts AF for 3 years

BOSTON – A single set of four injections with botulinum toxin into neuron-containing cardiac fat pads of patients during open-chest cardiac artery bypass surgery led to a long-term cut in the cumulative incidence of atrial tachyarrhythmias during 3-year follow-up in a pilot, sham-controlled study with 60 patients at two Russian centers.

“Because the favorable reduction of atrial fibrillation [AF] outlasted the anticipated botulinum toxin effects on autonomic nervous system activity, this may represent a form of autonomic reverse remodeling” triggered by just one injection of the paralyzing toxin at each of four intracardiac fat pads, Alexander B. Romanov, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. Botulinum toxin (BT) blocks neuronal release of acetylcholine, thereby interfering with cholinergic neurotransmission and producing hypothesized neurologic remodeling, explained Dr. Romanov, a researcher at the Meshalkin National Medical Research Center in Novosibirsk, Russia.

The 3-year results also showed statistically significant differences or trends favoring BT injections for several other clinical outcomes. Two deaths and two strokes occurred, all among the control patients. Two patients required a total of three hospitalizations during follow-up in the BT-treated group, compared with 10 patients hospitalized a total of 21 times in the control arm. Clinicians prescribed antiarrhythmic drugs to six of the BT-treated patients and to 15 of the controls.

All patients received an implanted heart rhythm monitor during their bypass surgery, and the researchers measured AF burden – the percentage of time during which AF occurred. After 12 months, 24 months, and 36 months, the AF burden averaged 0.2%, 1.6%, and 1.2%, respectively, in the BT-treated patients and 1.9%, 9.5%, and 6.9% in the sham-control patients.

“We don’t know why this works, but it’s a fascinating new approach that is worthy of further study,” commented Kalyanam Shivkumar, MD, professor and director of the Cardiac Arrhythmia Center at the University of California, Los Angeles, and designated discussant for the report.

“This is an extremely exciting study, but it remains inconclusive because how it works is not fully understood,” commented Andrew D. Krahn, MD, professor and chief of cardiology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

BOSTON – A single set of four injections with botulinum toxin into neuron-containing cardiac fat pads of patients during open-chest cardiac artery bypass surgery led to a long-term cut in the cumulative incidence of atrial tachyarrhythmias during 3-year follow-up in a pilot, sham-controlled study with 60 patients at two Russian centers.

“Because the favorable reduction of atrial fibrillation [AF] outlasted the anticipated botulinum toxin effects on autonomic nervous system activity, this may represent a form of autonomic reverse remodeling” triggered by just one injection of the paralyzing toxin at each of four intracardiac fat pads, Alexander B. Romanov, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. Botulinum toxin (BT) blocks neuronal release of acetylcholine, thereby interfering with cholinergic neurotransmission and producing hypothesized neurologic remodeling, explained Dr. Romanov, a researcher at the Meshalkin National Medical Research Center in Novosibirsk, Russia.

The 3-year results also showed statistically significant differences or trends favoring BT injections for several other clinical outcomes. Two deaths and two strokes occurred, all among the control patients. Two patients required a total of three hospitalizations during follow-up in the BT-treated group, compared with 10 patients hospitalized a total of 21 times in the control arm. Clinicians prescribed antiarrhythmic drugs to six of the BT-treated patients and to 15 of the controls.

All patients received an implanted heart rhythm monitor during their bypass surgery, and the researchers measured AF burden – the percentage of time during which AF occurred. After 12 months, 24 months, and 36 months, the AF burden averaged 0.2%, 1.6%, and 1.2%, respectively, in the BT-treated patients and 1.9%, 9.5%, and 6.9% in the sham-control patients.

“We don’t know why this works, but it’s a fascinating new approach that is worthy of further study,” commented Kalyanam Shivkumar, MD, professor and director of the Cardiac Arrhythmia Center at the University of California, Los Angeles, and designated discussant for the report.

“This is an extremely exciting study, but it remains inconclusive because how it works is not fully understood,” commented Andrew D. Krahn, MD, professor and chief of cardiology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

BOSTON – A single set of four injections with botulinum toxin into neuron-containing cardiac fat pads of patients during open-chest cardiac artery bypass surgery led to a long-term cut in the cumulative incidence of atrial tachyarrhythmias during 3-year follow-up in a pilot, sham-controlled study with 60 patients at two Russian centers.

“Because the favorable reduction of atrial fibrillation [AF] outlasted the anticipated botulinum toxin effects on autonomic nervous system activity, this may represent a form of autonomic reverse remodeling” triggered by just one injection of the paralyzing toxin at each of four intracardiac fat pads, Alexander B. Romanov, MD, said at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. Botulinum toxin (BT) blocks neuronal release of acetylcholine, thereby interfering with cholinergic neurotransmission and producing hypothesized neurologic remodeling, explained Dr. Romanov, a researcher at the Meshalkin National Medical Research Center in Novosibirsk, Russia.

The 3-year results also showed statistically significant differences or trends favoring BT injections for several other clinical outcomes. Two deaths and two strokes occurred, all among the control patients. Two patients required a total of three hospitalizations during follow-up in the BT-treated group, compared with 10 patients hospitalized a total of 21 times in the control arm. Clinicians prescribed antiarrhythmic drugs to six of the BT-treated patients and to 15 of the controls.

All patients received an implanted heart rhythm monitor during their bypass surgery, and the researchers measured AF burden – the percentage of time during which AF occurred. After 12 months, 24 months, and 36 months, the AF burden averaged 0.2%, 1.6%, and 1.2%, respectively, in the BT-treated patients and 1.9%, 9.5%, and 6.9% in the sham-control patients.

“We don’t know why this works, but it’s a fascinating new approach that is worthy of further study,” commented Kalyanam Shivkumar, MD, professor and director of the Cardiac Arrhythmia Center at the University of California, Los Angeles, and designated discussant for the report.

“This is an extremely exciting study, but it remains inconclusive because how it works is not fully understood,” commented Andrew D. Krahn, MD, professor and chief of cardiology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

REPORTING FROM HEART RHYTHM 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: During 3-year follow-up, atrial tachyarrhythmias occurred in 23% of botulinum toxin-treated patients and in 50% of sham controls.

Study details: Randomized, sham-controlled study with 60 patients at two Russian centers.

Disclosures: The study received no commercial funding. Dr. Romanov, Dr. Shivkumar, and Dr. Krahn had no relevant disclosures.

Source: Romanov A et al. Heart Rhythm 2018, Abstract B-LBCT02-01.

A fib ablation in HFrEF patients gains momentum

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BOSTON – Results from two recent trials suggest that cardiologists may have a new way to improve outcomes in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction if they also have atrial fibrillation: Cut the patient’s atrial fibrillation burden with catheter ablation.

This seemingly off-target approach to improving survival, avoiding heart failure hospitalizations, and possibly reducing other adverse events first gained attention with results from the CASTLE-AF (Catheter Ablation vs. Standard Conventional Treatment in Patients With LV Dysfunction and AF) randomized trial, first reported in 2017. The study showed in 363 patients that atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) led to a statistically significant 38% relative reduction in the primary endpoint of mortality or heart failure hospitalization during a median 38 months of follow-up (N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 1;378[5]:417-27).

This groundbreaking finding then received some degree of confirmation when Douglas L. Packer, MD, reported primary results from CABANA (Catheter Ablation vs Anti-arrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation Trial) at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. CABANA compared upfront ablation against first-line medical management of AF in 2,203 patients. While the primary endpoint of the cumulative rate of all-cause death, disabling stroke, serious bleeding, or cardiac arrest over a median follow-up of just over 4 years was neutral, with no statistically significant difference between the two treatment arms, a subgroup analysis showed a tantalizing suggestion of benefit in the 337 enrolled patients with a history of congestive heart failure (15% of the total study group).

In this subgroup, treatment with ablation cut the primary endpoint by 39% relative to those treated upfront with medical management, an effect that came close to statistical significance. In addition, Dr. Packer took special note of the per-protocol analysis, which censored out the crossover patients who constituted roughly a fifth of all enrolled patients. In the subgroup analysis using the per-protocol data, ablation was linked with a statistically significant 49% relative reduction in the primary endpoint among patients with a history of heart failure.

The patients for whom there may be the quickest shift to upfront ablation to treat AF based on the CABANA results will be those with heart failure and others with high underlying risk, Dr. Packer predicted at the meeting.

“The CASTLE-AF results were interesting, but in fewer than 400 patients. Now we’ve basically seen the same thing” in CABANA, said Dr. Packer, professor and a cardiac electrophysiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Notably however, the results Dr. Packer reported on the heart failure subgroup did not include any information on how many of these were patients who had HFrEF or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and how the apparent benefit from AF ablation affected each of these two heart failure types. In addition, the reported CABANA results did not have an endpoint result that completely matched the mortality and heart failure hospitalization composite endpoint used in CASTLE-AF. The closest endpoint that Dr. Packer reported from CABANA was a composite of mortality and cardiovascular hospitalization that showed, for the entire CABANA cohort, a statistically significant 17% relative reduction with ablation in the intention-to-treat analysis. Dr. Packer gave no data on how this outcome shook out in the subgroup of heart failure patients.

Despite these limitations, in trying to synthesize the CABANA and CASTLE-AF results, several electrophysiologists who heard the results agreed with Dr. Packer that the CABANA results confirmed the CASTLE-AF findings and helped strengthen the case for strongly considering AF ablation as first-line treatment in patients with heart failure.

“It’s clear that sinus rhythm is important in patients with heart failure. CASTLE-AF and now these results; that’s very strong to me,” said Eric N. Prystowsky, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist with the St. Vincent Medical Group in Indianapolis and designated discussant for CABANA at the meeting.

“It’s confirmatory,” said Nassir F. Marrouche, MD, lead investigator for CASTLE-AF, and professor and director of the electrophysiology laboratory at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

The “signal” of benefit from AF ablation in heart failure patients in CABANA “replicates what was seen in CASTLE-AF. The results are highly consistent and very important regarding how to treat patients with AF and heart failure,” said Jeremy N. Ruskin, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the cardiac arrhythmia service at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston. “The data strongly suggest that catheter ablation is helpful for restoring and preserving [heart] muscle function,” Dr. Ruskin said in a video interview. He noted that AF occurs in at least about a quarter of heart failure patients.

Other cardiologists at the meeting noted that, on the basis of the CASTLE-AF results alone, they have already become more aggressive about treating AF with ablation in patients with heart failure in routine practice.

“It adds to the armamentarium for treatment of patients with heart failure,” said Johannes Brachmann, MD, professor and chief of cardiology at the Coburg (Germany) Clinic and a senior coinvestigator for CASTLE-AF.

William T. Abraham, MD, a heart failure specialist at The Ohio State University in Columbus, offered a broader perspective on where AF diagnosis, treatment, and ablation currently stand in U.S. heart failure practice.

“There is a very tight link between AF burden and worse outcomes in heart failure, so there is something intuitively appealing about restoring sinus rhythm in heart failure patients. I think most heart failure clinicians believe, like me, that heart failure patients with AF benefit from restoration of normal sinus rhythm. But I don’t believe that the CASTLE-AF results have so far had much impact on practice, in part because it was a relatively small study. The heart failure community is looking for some confirmation,” said Dr. Abraham, professor and director of cardiovascular medicine at Ohio State.

“I think the CABANA results are encouraging, but they came from only 15% of the enrolled patients who also had heart failure. CABANA adds to our knowledge, but I’m not sure it’s definitive for the heart failure population. I’m not sure it tells us if you treat patients with heart failure with anti-arrhythmia drugs and successfully maintain sinus rhythm do those patients do just as well as those who get ablated,” he said in an interview. “I’d love to see a study of heart failure patients maintained in sinus rhythm with drugs compared with those treated with ablation.”

For most patients with heart failure, the coexistence of AF is identified because of AF symptoms, or when asymptomatic AF is found in recordings made by an implanted cardiac device. “I’m more aggressive about addressing asymptomatic AF in my heart failure patients, and I believe the heart failure community is moving rapidly in that direction because of the association between higher AF burden and worse heart failure outcomes,” Dr. Abraham said.

A more cautious view came from another heart failure specialist, Clyde Yancy, MD, professor and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University in Chicago. “It’s pretty evident that in certain patients with heart failure AF ablation might be the right treatment, but is it every HFrEF patient with AF?” he wondered. “It’s nice to have more evidence so we can be more comfortable sending heart failure patients for ablation, but I want to see more information about the risk” from ablation in heart failure patients, “the sustainability of the effect, and the consequences of ablation.”

But the reservations expressed by cardiologists like Dr. Yancy contrasted with the views of colleagues who consider the current evidence much more convincing.

“It seems logical to look harder for AF” in heart failure patients, based on the accumulated evidence from CASTLE-AF and CABANA, said Dr. Ruskin. “I don’t think we can offer advice to heart failure physicians to screen their heart failure patients for AF, but if it’s seen I think we have some useful information on how to address it.”

CASTLE-AF was funded by Biotronik. CABANA received partial funding from Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude. Dr. Packer has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude, and also from several other companies. Dr. Prystowsky as been a consultant to CardioNet and Medtronic, he has an equity interest in Stereotaxis, and he receives fellowship support from Medtronic and St. Jude. Dr. Marrouche has been a consultant to Biosense Webster, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and St. Jude. He has received research support from Medtronic, and he has had financial relationships with several other companies. Dr. Ruskin has been a consultant to Biosense Webster and Medtronic and several other companies, has an ownership interest in Amgen, Cameron Health, InfoBionic, Newpace, Portola, and Regeneron, and has a fiduciary role in Pharmaco-Kinesis. Dr. Russo and Dr. Yancy had no disclosures. Dr. Brachmann has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, St. Jude, and several other companies. Dr. Abraham has been a consultant to Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Novartis, and St. Jude.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BOSTON – Results from two recent trials suggest that cardiologists may have a new way to improve outcomes in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction if they also have atrial fibrillation: Cut the patient’s atrial fibrillation burden with catheter ablation.

This seemingly off-target approach to improving survival, avoiding heart failure hospitalizations, and possibly reducing other adverse events first gained attention with results from the CASTLE-AF (Catheter Ablation vs. Standard Conventional Treatment in Patients With LV Dysfunction and AF) randomized trial, first reported in 2017. The study showed in 363 patients that atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) led to a statistically significant 38% relative reduction in the primary endpoint of mortality or heart failure hospitalization during a median 38 months of follow-up (N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 1;378[5]:417-27).

This groundbreaking finding then received some degree of confirmation when Douglas L. Packer, MD, reported primary results from CABANA (Catheter Ablation vs Anti-arrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation Trial) at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. CABANA compared upfront ablation against first-line medical management of AF in 2,203 patients. While the primary endpoint of the cumulative rate of all-cause death, disabling stroke, serious bleeding, or cardiac arrest over a median follow-up of just over 4 years was neutral, with no statistically significant difference between the two treatment arms, a subgroup analysis showed a tantalizing suggestion of benefit in the 337 enrolled patients with a history of congestive heart failure (15% of the total study group).

In this subgroup, treatment with ablation cut the primary endpoint by 39% relative to those treated upfront with medical management, an effect that came close to statistical significance. In addition, Dr. Packer took special note of the per-protocol analysis, which censored out the crossover patients who constituted roughly a fifth of all enrolled patients. In the subgroup analysis using the per-protocol data, ablation was linked with a statistically significant 49% relative reduction in the primary endpoint among patients with a history of heart failure.

The patients for whom there may be the quickest shift to upfront ablation to treat AF based on the CABANA results will be those with heart failure and others with high underlying risk, Dr. Packer predicted at the meeting.

“The CASTLE-AF results were interesting, but in fewer than 400 patients. Now we’ve basically seen the same thing” in CABANA, said Dr. Packer, professor and a cardiac electrophysiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Notably however, the results Dr. Packer reported on the heart failure subgroup did not include any information on how many of these were patients who had HFrEF or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and how the apparent benefit from AF ablation affected each of these two heart failure types. In addition, the reported CABANA results did not have an endpoint result that completely matched the mortality and heart failure hospitalization composite endpoint used in CASTLE-AF. The closest endpoint that Dr. Packer reported from CABANA was a composite of mortality and cardiovascular hospitalization that showed, for the entire CABANA cohort, a statistically significant 17% relative reduction with ablation in the intention-to-treat analysis. Dr. Packer gave no data on how this outcome shook out in the subgroup of heart failure patients.

Despite these limitations, in trying to synthesize the CABANA and CASTLE-AF results, several electrophysiologists who heard the results agreed with Dr. Packer that the CABANA results confirmed the CASTLE-AF findings and helped strengthen the case for strongly considering AF ablation as first-line treatment in patients with heart failure.

“It’s clear that sinus rhythm is important in patients with heart failure. CASTLE-AF and now these results; that’s very strong to me,” said Eric N. Prystowsky, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist with the St. Vincent Medical Group in Indianapolis and designated discussant for CABANA at the meeting.

“It’s confirmatory,” said Nassir F. Marrouche, MD, lead investigator for CASTLE-AF, and professor and director of the electrophysiology laboratory at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

The “signal” of benefit from AF ablation in heart failure patients in CABANA “replicates what was seen in CASTLE-AF. The results are highly consistent and very important regarding how to treat patients with AF and heart failure,” said Jeremy N. Ruskin, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the cardiac arrhythmia service at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston. “The data strongly suggest that catheter ablation is helpful for restoring and preserving [heart] muscle function,” Dr. Ruskin said in a video interview. He noted that AF occurs in at least about a quarter of heart failure patients.

Other cardiologists at the meeting noted that, on the basis of the CASTLE-AF results alone, they have already become more aggressive about treating AF with ablation in patients with heart failure in routine practice.

“It adds to the armamentarium for treatment of patients with heart failure,” said Johannes Brachmann, MD, professor and chief of cardiology at the Coburg (Germany) Clinic and a senior coinvestigator for CASTLE-AF.

William T. Abraham, MD, a heart failure specialist at The Ohio State University in Columbus, offered a broader perspective on where AF diagnosis, treatment, and ablation currently stand in U.S. heart failure practice.

“There is a very tight link between AF burden and worse outcomes in heart failure, so there is something intuitively appealing about restoring sinus rhythm in heart failure patients. I think most heart failure clinicians believe, like me, that heart failure patients with AF benefit from restoration of normal sinus rhythm. But I don’t believe that the CASTLE-AF results have so far had much impact on practice, in part because it was a relatively small study. The heart failure community is looking for some confirmation,” said Dr. Abraham, professor and director of cardiovascular medicine at Ohio State.

“I think the CABANA results are encouraging, but they came from only 15% of the enrolled patients who also had heart failure. CABANA adds to our knowledge, but I’m not sure it’s definitive for the heart failure population. I’m not sure it tells us if you treat patients with heart failure with anti-arrhythmia drugs and successfully maintain sinus rhythm do those patients do just as well as those who get ablated,” he said in an interview. “I’d love to see a study of heart failure patients maintained in sinus rhythm with drugs compared with those treated with ablation.”

For most patients with heart failure, the coexistence of AF is identified because of AF symptoms, or when asymptomatic AF is found in recordings made by an implanted cardiac device. “I’m more aggressive about addressing asymptomatic AF in my heart failure patients, and I believe the heart failure community is moving rapidly in that direction because of the association between higher AF burden and worse heart failure outcomes,” Dr. Abraham said.

A more cautious view came from another heart failure specialist, Clyde Yancy, MD, professor and chief of cardiology at Northwestern University in Chicago. “It’s pretty evident that in certain patients with heart failure AF ablation might be the right treatment, but is it every HFrEF patient with AF?” he wondered. “It’s nice to have more evidence so we can be more comfortable sending heart failure patients for ablation, but I want to see more information about the risk” from ablation in heart failure patients, “the sustainability of the effect, and the consequences of ablation.”

But the reservations expressed by cardiologists like Dr. Yancy contrasted with the views of colleagues who consider the current evidence much more convincing.

“It seems logical to look harder for AF” in heart failure patients, based on the accumulated evidence from CASTLE-AF and CABANA, said Dr. Ruskin. “I don’t think we can offer advice to heart failure physicians to screen their heart failure patients for AF, but if it’s seen I think we have some useful information on how to address it.”

CASTLE-AF was funded by Biotronik. CABANA received partial funding from Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude. Dr. Packer has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude, and also from several other companies. Dr. Prystowsky as been a consultant to CardioNet and Medtronic, he has an equity interest in Stereotaxis, and he receives fellowship support from Medtronic and St. Jude. Dr. Marrouche has been a consultant to Biosense Webster, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and St. Jude. He has received research support from Medtronic, and he has had financial relationships with several other companies. Dr. Ruskin has been a consultant to Biosense Webster and Medtronic and several other companies, has an ownership interest in Amgen, Cameron Health, InfoBionic, Newpace, Portola, and Regeneron, and has a fiduciary role in Pharmaco-Kinesis. Dr. Russo and Dr. Yancy had no disclosures. Dr. Brachmann has been a consultant to and has received research funding from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, St. Jude, and several other companies. Dr. Abraham has been a consultant to Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Novartis, and St. Jude.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

BOSTON – Results from two recent trials suggest that cardiologists may have a new way to improve outcomes in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction if they also have atrial fibrillation: Cut the patient’s atrial fibrillation burden with catheter ablation.

This seemingly off-target approach to improving survival, avoiding heart failure hospitalizations, and possibly reducing other adverse events first gained attention with results from the CASTLE-AF (Catheter Ablation vs. Standard Conventional Treatment in Patients With LV Dysfunction and AF) randomized trial, first reported in 2017. The study showed in 363 patients that atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) led to a statistically significant 38% relative reduction in the primary endpoint of mortality or heart failure hospitalization during a median 38 months of follow-up (N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 1;378[5]:417-27).

This groundbreaking finding then received some degree of confirmation when Douglas L. Packer, MD, reported primary results from CABANA (Catheter Ablation vs Anti-arrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation Trial) at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society. CABANA compared upfront ablation against first-line medical management of AF in 2,203 patients. While the primary endpoint of the cumulative rate of all-cause death, disabling stroke, serious bleeding, or cardiac arrest over a median follow-up of just over 4 years was neutral, with no statistically significant difference between the two treatment arms, a subgroup analysis showed a tantalizing suggestion of benefit in the 337 enrolled patients with a history of congestive heart failure (15% of the total study group).

In this subgroup, treatment with ablation cut the primary endpoint by 39% relative to those treated upfront with medical management, an effect that came close to statistical significance. In addition, Dr. Packer took special note of the per-protocol analysis, which censored out the crossover patients who constituted roughly a fifth of all enrolled patients. In the subgroup analysis using the per-protocol data, ablation was linked with a statistically significant 49% relative reduction in the primary endpoint among patients with a history of heart failure.

The patients for whom there may be the quickest shift to upfront ablation to treat AF based on the CABANA results will be those with heart failure and others with high underlying risk, Dr. Packer predicted at the meeting.

“The CASTLE-AF results were interesting, but in fewer than 400 patients. Now we’ve basically seen the same thing” in CABANA, said Dr. Packer, professor and a cardiac electrophysiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

Notably however, the results Dr. Packer reported on the heart failure subgroup did not include any information on how many of these were patients who had HFrEF or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and how the apparent benefit from AF ablation affected each of these two heart failure types. In addition, the reported CABANA results did not have an endpoint result that completely matched the mortality and heart failure hospitalization composite endpoint used in CASTLE-AF. The closest endpoint that Dr. Packer reported from CABANA was a composite of mortality and cardiovascular hospitalization that showed, for the entire CABANA cohort, a statistically significant 17% relative reduction with ablation in the intention-to-treat analysis. Dr. Packer gave no data on how this outcome shook out in the subgroup of heart failure patients.

Despite these limitations, in trying to synthesize the CABANA and CASTLE-AF results, several electrophysiologists who heard the results agreed with Dr. Packer that the CABANA results confirmed the CASTLE-AF findings and helped strengthen the case for strongly considering AF ablation as first-line treatment in patients with heart failure.

“It’s clear that sinus rhythm is important in patients with heart failure. CASTLE-AF and now these results; that’s very strong to me,” said Eric N. Prystowsky, MD, a cardiac electrophysiologist with the St. Vincent Medical Group in Indianapolis and designated discussant for CABANA at the meeting.

“It’s confirmatory,” said Nassir F. Marrouche, MD, lead investigator for CASTLE-AF, and professor and director of the electrophysiology laboratory at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

The “signal” of benefit from AF ablation in heart failure patients in CABANA “replicates what was seen in CASTLE-AF. The results are highly consistent and very important regarding how to treat patients with AF and heart failure,” said Jeremy N. Ruskin, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the cardiac arrhythmia service at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston. “The data strongly suggest that catheter ablation is helpful for restoring and preserving [heart] muscle function,” Dr. Ruskin said in a video interview. He noted that AF occurs in at least about a quarter of heart failure patients.

Other cardiologists at the meeting noted that, on the basis of the CASTLE-AF results alone, they have already become more aggressive about treating AF with ablation in patients with heart failure in routine practice.

“It adds to the armamentarium for treatment of patients with heart failure,” said Johannes Brachmann, MD, professor and chief of cardiology at the Coburg (Germany) Clinic and a senior coinvestigator for CASTLE-AF.

William T. Abraham, MD, a heart failure specialist at The Ohio State University in Columbus, offered a broader perspective on where AF diagnosis, treatment, and ablation currently stand in U.S. heart failure practice.