User login

Prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) stays, variably defined as > 48 h to > 14 days, are a known complication of cardiac surgery.1-8 Prolonged stays are associated with higher resource utilization and higher mortality.2,3,9-12 Although there are several cardiac surgery risk models that can be used preoperatively to identify patients at risk for prolonged ICU stay, factors that influence outcomes for patients who experience prolonged ICU stays are poorly understood.2,13-19 Little information is available to inform discussions between health care practitioners (HCPs) and patients throughout a prolonged ICU stay, especially those ≥ 7 days.

As cardiac surgical complexity, patient age, and preexisting comorbidities have increased over time, so has the need to provide patients and HCPs with data to inform decision making, enhance prognostication, and set realistic expectations at varying time intervals during prolonged ICU stay. The purpose of this study was to evaluate short- and long-term outcomes in cardiac surgery patients after prolonged ICU stays at relevant time intervals (7, 14, 21, and 28 days) and to determine factors that may predict a patient’s outcome after a prolonged ICU stay.

Methods

The University of Michigan Health System Institutional Review Board approved this study and waived informed consent. We merged the University of Michigan Medical Center Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database, which is updated periodically with late mortality, with elements of the electronic health record (EHR). Adult patients were included if they had cardiac surgery at the University of Michigan between January 2, 2001, and December 31, 2011. Late mortality was updated through December 1, 2014. Data are presented as frequency (%), mean (SD), and median (IQR) as appropriate. Bivariate comparisons between survivors and nonsurvivors were done with χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical data, Student t test for continuous normally distributed data, and Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous not normally distributed data. To determine factors associated with operative mortality (death within 30 days of surgery or hospital discharge, whichever occurred later), we used logistic regression with forward selection. All available factors were initially entered in the models.

Separate logistic models were created based on all data available at days 7, 14, 21, and 28. Final models consisted of factors with statistically significant P values (< .05) and adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% CIs that excluded 1. To determine factors associated with late mortality, we used a Cox proportional hazard model, which used data available at discharge and STS complications. As these complications did not include their timing, they could only be used in models created at discharge and not for days 7, 14, 21, and 28 models. Final models consisted of factors with P values < .05 and 95% CIs of the AORs or the hazard ratios (HRs) that excluded 1. As the EHR did not start recording data until January 2, 2004, and its capture of data remained incomplete for several years, rather than imputing these missing data or excluding these patients, we chose to create an extra categorical level for each factor to represent missing data. For continuous factors with missing data, we first converted the continuous data to terciles and the missing data became the fourth level.20,21

The discrimination of the logistic models were determined by the c-statistic and for the Cox proportional hazards model with the Harrell concordance index (C index). Time trends were assessed with the Cochran-Armitage trend test. P < .05 was deemed statistically significant. Statistics were calculated with SPSS versions 21-23 or SAS 9.4.

Results

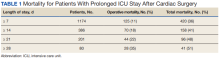

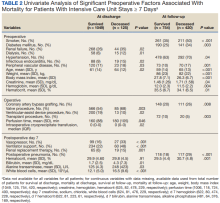

Of 8309 admissions to the ICU after cardiac surgery, 1174 (14%) had ICU stays ≥ 7 days, 386 (5%) ≥ 14 days, 201 (2%) ≥ 21 days, and 80 (0.9%) ≥ 28 days. The prolonged ICU study population was mostly male, White race, with a mean (SD) age of 62 (14) years. Patients had a variety of comorbidities, most notably 61% had hypertension and half had heart failure. Valve surgery (55%) was the most common procedure (n = 651). Twenty-nine percent required > 1 procedure (eAppendix 1).

The operative mortality

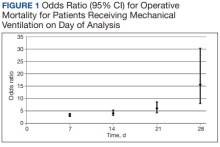

Using multivariable logistic regression to adjust for factors associated with mortality, we found that receiving mechanical ventilation on the day of analysis was associated with increased operative mortality with AOR increasing from 3.35 (95% CI, 2.82-3.98) for

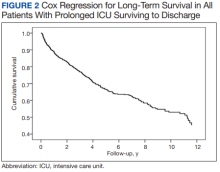

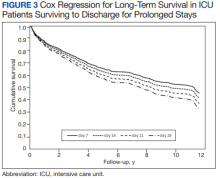

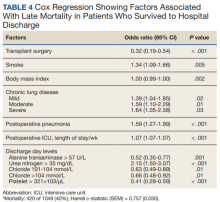

After multivariable Cox regression to adjust for confounders, we found that each postoperative week was associated with a 7% higher hazard of dying (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.07-1.07; P < .001). Postoperative pneumonia was also associated with increased hazard of dying (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.27-1.99; P < .001),

Discussion

We found that operative mortality increased the longer the patient stayed in the ICU, ranging from 11% for ≥ 7 days to 35% for ≥ 28 days. We further found that in ICU survivors, median (IQR) survival was 10.7 (0.7) years. While previous studies have evaluated prolonged ICU stays, they have been limited by studying limited subpopulations, such as patients who are dependent on dialysis or octogenarians, or used a single cutoff to define prolonged ICU stays, variably defined from > 48 hours to > 14 days.2-7,9-12,22 Our study is similar to others that used ≥ 2 cutoffs.1,8 However, our study was novel by providing 4 cutoffs to improve temporal prediction of hospital outcomes. Unlike a study by Ryan and colleagues, which found no increase in mortality with longer stay (43.5% for ≥ 14 days and 45% for ≥ 28 days), our study findings are similar to those of Yu and colleagues (11.1% mortality for prolonged ICU stays of 1 to 2 weeks, 26.6% for 2 to 4 weeks, and 31% for > 4 weeks) and others (8%, 3 to 14 days; 40%, >14 days; 10%, 1 to 2 weeks; 25.7% > 2 weeks) in finding a progressively increased hospital mortality with longer ICU stays.1,4,5,8 These differences may be related to different ICU populations or to improvements in care since Ryan and colleagues study was conducted.

Fewer studies have evaluated factors associated with mortality in cardiac surgery prolonged ICU stay patients. Our study is similar to other studies that evaluated risk factors by finding associations between a variety of comorbidities and process of care associated with both operative and long-term mortality; however, comparison between these studies is limited by the varying factors analyzed.1,3,5,6,8,9,11 We found that mechanical ventilation on days 7, 14, 21, and 28 was strongly associated with operative mortality, similar to noncardiac surgery patients and cardiac surgery patients.6,23,24 While we found several processes of care, such as catecholamine use and transfusions to be associated with mortality, which is similar to other studies, notably, we did not find an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality.1,25 While there is an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality in ICU patients, its status in cardiac surgery patients with prolonged ICU stays is less clear.26 While Ryan and colleagues found an association between renal replacement therapy and hospital mortality in patients staying ≥ 14 days, they did not find it in patients staying ≥.

28 days.1 Other studies of prolonged ICU stays for cardiac surgery patients have also failed to find an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality.5,6,9 Importantly, practice that expedites liberation from mechanical ventilation, such as fast tracking, daily spontaneous breathing trials, extubation to noninvasive respiratory support, and pulmonary rehabilitation may all have potential to limit mechanical ventilation duration and improve hospital survival and deserve further study.27-29Median (IQR) survival in hospital survivors was 10.7 (0.7) years, which is generally better than previously reported, but similar to that reported by Silberman and colleagues.2,4,6,8,11,12 Differences between these studies may relate to different patient populations within the cardiac surgery ICUs, definitions of prolonged ICU stays, or eras of care. Further study is needed to clarify these discrepancies. We found that cardiac transplantation and obesity were associated with the least risk of dying, while smoking, lung disease, and postoperative pneumonia were independently associated with increased hazard of dying. The obesity paradox, where obesity is protective, has been previously observed in cardiac surgery patients.30

Strengths and Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. This is a single center study, and our patient population and processes of care may differ from other centers, limiting its generalizability. Notably, we do fewer coronary bypass operations and more aortic reconstructions and ventricular assist device insertions than do many other centers. Second, we did not have laboratory values for about one-third of patients (preceded EHR implementation). However, we were able to compensate for this by binning values and including missing data as an extra bin.20,21

The main strength of this study is that we were able to combine disparate records to assess a large number of potential factors associated with both operative and long-term mortality. This produced models that had good to very good discrimination. By producing models at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days to predict operative mortality and a model at discharge, it may help to provide objective data to facilitate conversations with patients and their families. However, further studies to externally validate these models should be conducted.

Conclusions

We found that longer prolonged ICU stays are associated with both operative and late mortality. Receiving mechanical ventilation on days 7, 14, 21, or 28 was strongly associated with operative mortality.

1. Ryan TA, Rady MY, Bashour A, Leventhal M, Lytle B, Starr NJ. Predictors of outcome in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care stay. Chest. 1997;112(4):1035-1042. doi:10.1378/chest.112.4.1035

2. Hein OV, Birnbaum J, Wernecke K, England M, Konertz W, Spies C. Prolonged intensive care unit stay in cardiac surgery: risk factors and long-term-survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(3):880-885. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.09.077

3. Mahesh B, Choong CK, Goldsmith K, Gerrard C, Nashef SA, Vuylsteke A. Prolonged stay in intensive care unit is a powerful predictor of adverse outcomes after cardiac operations. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2012;94(1):109-116. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.02.010

4. Silberman S, Bitran D, Fink D, Tauber R, Merin O. Very prolonged stay in the intensive care unit after cardiac operations: early results and late survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(1):15-21. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.01.103

5. Lapar DJ, Gillen JR, Crosby IK, et al. Predictors of operative mortality in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care unit duration. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(6):1116-1123. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.02.028

6. Manji RA, Arora RC, Singal RK, et al. Long-term outcome and predictors of noninstitutionalized survival subsequent to prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgical procedures. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(1):56-63. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.004

7. Augustin P, Tanaka S, Chhor V, et al. Prognosis of prolonged intensive care unit stay after aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis in octogenarians. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30(6):1555-1561. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2016.07.029

8. Yu PJ, Cassiere HA, Fishbein J, Esposito RA, Hartman AR. Outcomes of patients with prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30(6):1550-1554. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2016.03.145

9. Bashour CA, Yared JP, Ryan TA, et al. Long-term survival and functional capacity in cardiac surgery patients after prolonged intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(12):3847-3853. doi:10.1097/00003246-200012000-00018

10. Isgro F, Skuras JA, Kiessling AH, Lehmann A, Saggau W. Survival and quality of life after a long-term intensive care stay. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;50(2):95-99. doi:10.1055/s-2002-26693

11. Williams MR, Wellner RB, Hartnett EA, Hartnett EA, Thornton B, Kavarana MN, Mahapatra R, Oz MC Sladen R. Long-term survival and quality of life in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care unit length of stay. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73(5):1472-1478.

12. Lagercrantz E, Lindblom D, Sartipy U. Survival and quality of life in cardiac surgery patients with prolonged intensive care. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:490-495. doi:10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03464-1

13. Edwards FH, Clark RE, Schwartz M. Coronary artery bypass grafting: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57(1):12-19. doi:10.1016/0003-4975(94)90358-1

14. Lawrence DR, Valencia O, Smith EE, Murday A, Treasure T. Parsonnet score is a good predictor of the duration of intensive care unit stay following cardiac surgery. Heart. 2000;83(4):429-432. doi:10.1136/heart.83.4.429

15. Janssen DP, Noyez L, Wouters C, Brouwer RM. Preoperative prediction of prolonged stay in the intensive care unit for coronary bypass surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25(2):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2003.11.005

16. Nilsson J, Algotsson L, Hoglund P, Luhrs C, Brandt J. EuroSCORE predicts intensive care unit stay and costs of open heart surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(5):1528-1534. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.060

17. Ghotkar SV, Grayson AD, Fabri BM, Dihmis WC, Pullan DM. Preoperative calculation of risk for prolonged intensive care unit stay following coronary artery bypass grafting. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;1:14. doi:10.1186/1749-8090-1-1418. Messaoudi N, Decocker J, Stockman BA, Bossaert LL, Rodrigus IE. Is EuroSCORE useful in the prediction of extended intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery? Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2009;36(1):35-39. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.02.007

19. Ettema RG, Peelen LM, Schuurmans MJ, Nierich AP, Kalkman CJ, Moons KG. Prediction models for prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery: systematic review and validation study. Circulation. 2010;122(7):682-689. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.926808

20. Engoren M. Does erythrocyte blood transfusion prevent acute kidney injury? Propensity-matched case control analysis. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(5):1126-1133. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e181f70f56

21. UK National Centre for Research Methods. Minimising the effect of missing data. Revised July 22, 2011. Accessed June 28, 2022. www.restore.ac.uk/srme/www/fac/soc/wie/research-new/srme/modules/mod3/9/index.html.

22. Leontyev S, Davierwala PM, Gaube LM, et al. Outcomes of dialysis-dependent patients after cardiac operations in a single-center experience of 483 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):1270-1276. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.07.05223. Freundlich RE, Maile MD, Sferra JJ, Jewell ES, Kheterpal S, Engoren M. Complications associated with mortality in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Database. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(1):55-62. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000002799

24. Freundlich RE, Maile MD, Hajjar MM, et al. Years of life lost after complications of coronary artery bypass operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(6):1893-1899. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.048

25. Koch CG, Li L, Sessler DI, et al. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(12):1229-1239. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa070403

26. Truche AS, Ragey SP, Souweine B, et al. ICU survival and need of renal replacement therapy with respect to AKI duration in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):127. doi:10.1186/s13613-018-0467-6

27. Kollef MH, Shapiro SD, Silver P, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of protocol-directed versus physician-directed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(4):567-574. doi:10.1097/00003246-199704000-00004

28. McWilliams D, Weblin J, Atkins G, et al. Enhancing rehabilitation of mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit: a quality improvement project. J Crit Care. 2015;30(1):13-18. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.09.018

29. Hernandez G, Vaquero C, Gonzalez P, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1354-1361. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2711

30. Schwann TA, Ramira PS, Engoren MC, et al. Evidence and temporality of the obesity paradox in coronary bypass surgery: an analysis of cause-specific mortality. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;54(5):896-903. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezy207

Prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) stays, variably defined as > 48 h to > 14 days, are a known complication of cardiac surgery.1-8 Prolonged stays are associated with higher resource utilization and higher mortality.2,3,9-12 Although there are several cardiac surgery risk models that can be used preoperatively to identify patients at risk for prolonged ICU stay, factors that influence outcomes for patients who experience prolonged ICU stays are poorly understood.2,13-19 Little information is available to inform discussions between health care practitioners (HCPs) and patients throughout a prolonged ICU stay, especially those ≥ 7 days.

As cardiac surgical complexity, patient age, and preexisting comorbidities have increased over time, so has the need to provide patients and HCPs with data to inform decision making, enhance prognostication, and set realistic expectations at varying time intervals during prolonged ICU stay. The purpose of this study was to evaluate short- and long-term outcomes in cardiac surgery patients after prolonged ICU stays at relevant time intervals (7, 14, 21, and 28 days) and to determine factors that may predict a patient’s outcome after a prolonged ICU stay.

Methods

The University of Michigan Health System Institutional Review Board approved this study and waived informed consent. We merged the University of Michigan Medical Center Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database, which is updated periodically with late mortality, with elements of the electronic health record (EHR). Adult patients were included if they had cardiac surgery at the University of Michigan between January 2, 2001, and December 31, 2011. Late mortality was updated through December 1, 2014. Data are presented as frequency (%), mean (SD), and median (IQR) as appropriate. Bivariate comparisons between survivors and nonsurvivors were done with χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical data, Student t test for continuous normally distributed data, and Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous not normally distributed data. To determine factors associated with operative mortality (death within 30 days of surgery or hospital discharge, whichever occurred later), we used logistic regression with forward selection. All available factors were initially entered in the models.

Separate logistic models were created based on all data available at days 7, 14, 21, and 28. Final models consisted of factors with statistically significant P values (< .05) and adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% CIs that excluded 1. To determine factors associated with late mortality, we used a Cox proportional hazard model, which used data available at discharge and STS complications. As these complications did not include their timing, they could only be used in models created at discharge and not for days 7, 14, 21, and 28 models. Final models consisted of factors with P values < .05 and 95% CIs of the AORs or the hazard ratios (HRs) that excluded 1. As the EHR did not start recording data until January 2, 2004, and its capture of data remained incomplete for several years, rather than imputing these missing data or excluding these patients, we chose to create an extra categorical level for each factor to represent missing data. For continuous factors with missing data, we first converted the continuous data to terciles and the missing data became the fourth level.20,21

The discrimination of the logistic models were determined by the c-statistic and for the Cox proportional hazards model with the Harrell concordance index (C index). Time trends were assessed with the Cochran-Armitage trend test. P < .05 was deemed statistically significant. Statistics were calculated with SPSS versions 21-23 or SAS 9.4.

Results

Of 8309 admissions to the ICU after cardiac surgery, 1174 (14%) had ICU stays ≥ 7 days, 386 (5%) ≥ 14 days, 201 (2%) ≥ 21 days, and 80 (0.9%) ≥ 28 days. The prolonged ICU study population was mostly male, White race, with a mean (SD) age of 62 (14) years. Patients had a variety of comorbidities, most notably 61% had hypertension and half had heart failure. Valve surgery (55%) was the most common procedure (n = 651). Twenty-nine percent required > 1 procedure (eAppendix 1).

The operative mortality

Using multivariable logistic regression to adjust for factors associated with mortality, we found that receiving mechanical ventilation on the day of analysis was associated with increased operative mortality with AOR increasing from 3.35 (95% CI, 2.82-3.98) for

After multivariable Cox regression to adjust for confounders, we found that each postoperative week was associated with a 7% higher hazard of dying (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.07-1.07; P < .001). Postoperative pneumonia was also associated with increased hazard of dying (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.27-1.99; P < .001),

Discussion

We found that operative mortality increased the longer the patient stayed in the ICU, ranging from 11% for ≥ 7 days to 35% for ≥ 28 days. We further found that in ICU survivors, median (IQR) survival was 10.7 (0.7) years. While previous studies have evaluated prolonged ICU stays, they have been limited by studying limited subpopulations, such as patients who are dependent on dialysis or octogenarians, or used a single cutoff to define prolonged ICU stays, variably defined from > 48 hours to > 14 days.2-7,9-12,22 Our study is similar to others that used ≥ 2 cutoffs.1,8 However, our study was novel by providing 4 cutoffs to improve temporal prediction of hospital outcomes. Unlike a study by Ryan and colleagues, which found no increase in mortality with longer stay (43.5% for ≥ 14 days and 45% for ≥ 28 days), our study findings are similar to those of Yu and colleagues (11.1% mortality for prolonged ICU stays of 1 to 2 weeks, 26.6% for 2 to 4 weeks, and 31% for > 4 weeks) and others (8%, 3 to 14 days; 40%, >14 days; 10%, 1 to 2 weeks; 25.7% > 2 weeks) in finding a progressively increased hospital mortality with longer ICU stays.1,4,5,8 These differences may be related to different ICU populations or to improvements in care since Ryan and colleagues study was conducted.

Fewer studies have evaluated factors associated with mortality in cardiac surgery prolonged ICU stay patients. Our study is similar to other studies that evaluated risk factors by finding associations between a variety of comorbidities and process of care associated with both operative and long-term mortality; however, comparison between these studies is limited by the varying factors analyzed.1,3,5,6,8,9,11 We found that mechanical ventilation on days 7, 14, 21, and 28 was strongly associated with operative mortality, similar to noncardiac surgery patients and cardiac surgery patients.6,23,24 While we found several processes of care, such as catecholamine use and transfusions to be associated with mortality, which is similar to other studies, notably, we did not find an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality.1,25 While there is an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality in ICU patients, its status in cardiac surgery patients with prolonged ICU stays is less clear.26 While Ryan and colleagues found an association between renal replacement therapy and hospital mortality in patients staying ≥ 14 days, they did not find it in patients staying ≥.

28 days.1 Other studies of prolonged ICU stays for cardiac surgery patients have also failed to find an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality.5,6,9 Importantly, practice that expedites liberation from mechanical ventilation, such as fast tracking, daily spontaneous breathing trials, extubation to noninvasive respiratory support, and pulmonary rehabilitation may all have potential to limit mechanical ventilation duration and improve hospital survival and deserve further study.27-29Median (IQR) survival in hospital survivors was 10.7 (0.7) years, which is generally better than previously reported, but similar to that reported by Silberman and colleagues.2,4,6,8,11,12 Differences between these studies may relate to different patient populations within the cardiac surgery ICUs, definitions of prolonged ICU stays, or eras of care. Further study is needed to clarify these discrepancies. We found that cardiac transplantation and obesity were associated with the least risk of dying, while smoking, lung disease, and postoperative pneumonia were independently associated with increased hazard of dying. The obesity paradox, where obesity is protective, has been previously observed in cardiac surgery patients.30

Strengths and Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. This is a single center study, and our patient population and processes of care may differ from other centers, limiting its generalizability. Notably, we do fewer coronary bypass operations and more aortic reconstructions and ventricular assist device insertions than do many other centers. Second, we did not have laboratory values for about one-third of patients (preceded EHR implementation). However, we were able to compensate for this by binning values and including missing data as an extra bin.20,21

The main strength of this study is that we were able to combine disparate records to assess a large number of potential factors associated with both operative and long-term mortality. This produced models that had good to very good discrimination. By producing models at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days to predict operative mortality and a model at discharge, it may help to provide objective data to facilitate conversations with patients and their families. However, further studies to externally validate these models should be conducted.

Conclusions

We found that longer prolonged ICU stays are associated with both operative and late mortality. Receiving mechanical ventilation on days 7, 14, 21, or 28 was strongly associated with operative mortality.

Prolonged intensive care unit (ICU) stays, variably defined as > 48 h to > 14 days, are a known complication of cardiac surgery.1-8 Prolonged stays are associated with higher resource utilization and higher mortality.2,3,9-12 Although there are several cardiac surgery risk models that can be used preoperatively to identify patients at risk for prolonged ICU stay, factors that influence outcomes for patients who experience prolonged ICU stays are poorly understood.2,13-19 Little information is available to inform discussions between health care practitioners (HCPs) and patients throughout a prolonged ICU stay, especially those ≥ 7 days.

As cardiac surgical complexity, patient age, and preexisting comorbidities have increased over time, so has the need to provide patients and HCPs with data to inform decision making, enhance prognostication, and set realistic expectations at varying time intervals during prolonged ICU stay. The purpose of this study was to evaluate short- and long-term outcomes in cardiac surgery patients after prolonged ICU stays at relevant time intervals (7, 14, 21, and 28 days) and to determine factors that may predict a patient’s outcome after a prolonged ICU stay.

Methods

The University of Michigan Health System Institutional Review Board approved this study and waived informed consent. We merged the University of Michigan Medical Center Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) database, which is updated periodically with late mortality, with elements of the electronic health record (EHR). Adult patients were included if they had cardiac surgery at the University of Michigan between January 2, 2001, and December 31, 2011. Late mortality was updated through December 1, 2014. Data are presented as frequency (%), mean (SD), and median (IQR) as appropriate. Bivariate comparisons between survivors and nonsurvivors were done with χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical data, Student t test for continuous normally distributed data, and Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous not normally distributed data. To determine factors associated with operative mortality (death within 30 days of surgery or hospital discharge, whichever occurred later), we used logistic regression with forward selection. All available factors were initially entered in the models.

Separate logistic models were created based on all data available at days 7, 14, 21, and 28. Final models consisted of factors with statistically significant P values (< .05) and adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% CIs that excluded 1. To determine factors associated with late mortality, we used a Cox proportional hazard model, which used data available at discharge and STS complications. As these complications did not include their timing, they could only be used in models created at discharge and not for days 7, 14, 21, and 28 models. Final models consisted of factors with P values < .05 and 95% CIs of the AORs or the hazard ratios (HRs) that excluded 1. As the EHR did not start recording data until January 2, 2004, and its capture of data remained incomplete for several years, rather than imputing these missing data or excluding these patients, we chose to create an extra categorical level for each factor to represent missing data. For continuous factors with missing data, we first converted the continuous data to terciles and the missing data became the fourth level.20,21

The discrimination of the logistic models were determined by the c-statistic and for the Cox proportional hazards model with the Harrell concordance index (C index). Time trends were assessed with the Cochran-Armitage trend test. P < .05 was deemed statistically significant. Statistics were calculated with SPSS versions 21-23 or SAS 9.4.

Results

Of 8309 admissions to the ICU after cardiac surgery, 1174 (14%) had ICU stays ≥ 7 days, 386 (5%) ≥ 14 days, 201 (2%) ≥ 21 days, and 80 (0.9%) ≥ 28 days. The prolonged ICU study population was mostly male, White race, with a mean (SD) age of 62 (14) years. Patients had a variety of comorbidities, most notably 61% had hypertension and half had heart failure. Valve surgery (55%) was the most common procedure (n = 651). Twenty-nine percent required > 1 procedure (eAppendix 1).

The operative mortality

Using multivariable logistic regression to adjust for factors associated with mortality, we found that receiving mechanical ventilation on the day of analysis was associated with increased operative mortality with AOR increasing from 3.35 (95% CI, 2.82-3.98) for

After multivariable Cox regression to adjust for confounders, we found that each postoperative week was associated with a 7% higher hazard of dying (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.07-1.07; P < .001). Postoperative pneumonia was also associated with increased hazard of dying (HR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.27-1.99; P < .001),

Discussion

We found that operative mortality increased the longer the patient stayed in the ICU, ranging from 11% for ≥ 7 days to 35% for ≥ 28 days. We further found that in ICU survivors, median (IQR) survival was 10.7 (0.7) years. While previous studies have evaluated prolonged ICU stays, they have been limited by studying limited subpopulations, such as patients who are dependent on dialysis or octogenarians, or used a single cutoff to define prolonged ICU stays, variably defined from > 48 hours to > 14 days.2-7,9-12,22 Our study is similar to others that used ≥ 2 cutoffs.1,8 However, our study was novel by providing 4 cutoffs to improve temporal prediction of hospital outcomes. Unlike a study by Ryan and colleagues, which found no increase in mortality with longer stay (43.5% for ≥ 14 days and 45% for ≥ 28 days), our study findings are similar to those of Yu and colleagues (11.1% mortality for prolonged ICU stays of 1 to 2 weeks, 26.6% for 2 to 4 weeks, and 31% for > 4 weeks) and others (8%, 3 to 14 days; 40%, >14 days; 10%, 1 to 2 weeks; 25.7% > 2 weeks) in finding a progressively increased hospital mortality with longer ICU stays.1,4,5,8 These differences may be related to different ICU populations or to improvements in care since Ryan and colleagues study was conducted.

Fewer studies have evaluated factors associated with mortality in cardiac surgery prolonged ICU stay patients. Our study is similar to other studies that evaluated risk factors by finding associations between a variety of comorbidities and process of care associated with both operative and long-term mortality; however, comparison between these studies is limited by the varying factors analyzed.1,3,5,6,8,9,11 We found that mechanical ventilation on days 7, 14, 21, and 28 was strongly associated with operative mortality, similar to noncardiac surgery patients and cardiac surgery patients.6,23,24 While we found several processes of care, such as catecholamine use and transfusions to be associated with mortality, which is similar to other studies, notably, we did not find an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality.1,25 While there is an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality in ICU patients, its status in cardiac surgery patients with prolonged ICU stays is less clear.26 While Ryan and colleagues found an association between renal replacement therapy and hospital mortality in patients staying ≥ 14 days, they did not find it in patients staying ≥.

28 days.1 Other studies of prolonged ICU stays for cardiac surgery patients have also failed to find an association between renal replacement therapy and mortality.5,6,9 Importantly, practice that expedites liberation from mechanical ventilation, such as fast tracking, daily spontaneous breathing trials, extubation to noninvasive respiratory support, and pulmonary rehabilitation may all have potential to limit mechanical ventilation duration and improve hospital survival and deserve further study.27-29Median (IQR) survival in hospital survivors was 10.7 (0.7) years, which is generally better than previously reported, but similar to that reported by Silberman and colleagues.2,4,6,8,11,12 Differences between these studies may relate to different patient populations within the cardiac surgery ICUs, definitions of prolonged ICU stays, or eras of care. Further study is needed to clarify these discrepancies. We found that cardiac transplantation and obesity were associated with the least risk of dying, while smoking, lung disease, and postoperative pneumonia were independently associated with increased hazard of dying. The obesity paradox, where obesity is protective, has been previously observed in cardiac surgery patients.30

Strengths and Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. This is a single center study, and our patient population and processes of care may differ from other centers, limiting its generalizability. Notably, we do fewer coronary bypass operations and more aortic reconstructions and ventricular assist device insertions than do many other centers. Second, we did not have laboratory values for about one-third of patients (preceded EHR implementation). However, we were able to compensate for this by binning values and including missing data as an extra bin.20,21

The main strength of this study is that we were able to combine disparate records to assess a large number of potential factors associated with both operative and long-term mortality. This produced models that had good to very good discrimination. By producing models at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days to predict operative mortality and a model at discharge, it may help to provide objective data to facilitate conversations with patients and their families. However, further studies to externally validate these models should be conducted.

Conclusions

We found that longer prolonged ICU stays are associated with both operative and late mortality. Receiving mechanical ventilation on days 7, 14, 21, or 28 was strongly associated with operative mortality.

1. Ryan TA, Rady MY, Bashour A, Leventhal M, Lytle B, Starr NJ. Predictors of outcome in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care stay. Chest. 1997;112(4):1035-1042. doi:10.1378/chest.112.4.1035

2. Hein OV, Birnbaum J, Wernecke K, England M, Konertz W, Spies C. Prolonged intensive care unit stay in cardiac surgery: risk factors and long-term-survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(3):880-885. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.09.077

3. Mahesh B, Choong CK, Goldsmith K, Gerrard C, Nashef SA, Vuylsteke A. Prolonged stay in intensive care unit is a powerful predictor of adverse outcomes after cardiac operations. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2012;94(1):109-116. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.02.010

4. Silberman S, Bitran D, Fink D, Tauber R, Merin O. Very prolonged stay in the intensive care unit after cardiac operations: early results and late survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(1):15-21. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.01.103

5. Lapar DJ, Gillen JR, Crosby IK, et al. Predictors of operative mortality in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care unit duration. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(6):1116-1123. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.02.028

6. Manji RA, Arora RC, Singal RK, et al. Long-term outcome and predictors of noninstitutionalized survival subsequent to prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgical procedures. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(1):56-63. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.004

7. Augustin P, Tanaka S, Chhor V, et al. Prognosis of prolonged intensive care unit stay after aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis in octogenarians. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30(6):1555-1561. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2016.07.029

8. Yu PJ, Cassiere HA, Fishbein J, Esposito RA, Hartman AR. Outcomes of patients with prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30(6):1550-1554. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2016.03.145

9. Bashour CA, Yared JP, Ryan TA, et al. Long-term survival and functional capacity in cardiac surgery patients after prolonged intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(12):3847-3853. doi:10.1097/00003246-200012000-00018

10. Isgro F, Skuras JA, Kiessling AH, Lehmann A, Saggau W. Survival and quality of life after a long-term intensive care stay. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;50(2):95-99. doi:10.1055/s-2002-26693

11. Williams MR, Wellner RB, Hartnett EA, Hartnett EA, Thornton B, Kavarana MN, Mahapatra R, Oz MC Sladen R. Long-term survival and quality of life in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care unit length of stay. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73(5):1472-1478.

12. Lagercrantz E, Lindblom D, Sartipy U. Survival and quality of life in cardiac surgery patients with prolonged intensive care. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:490-495. doi:10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03464-1

13. Edwards FH, Clark RE, Schwartz M. Coronary artery bypass grafting: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57(1):12-19. doi:10.1016/0003-4975(94)90358-1

14. Lawrence DR, Valencia O, Smith EE, Murday A, Treasure T. Parsonnet score is a good predictor of the duration of intensive care unit stay following cardiac surgery. Heart. 2000;83(4):429-432. doi:10.1136/heart.83.4.429

15. Janssen DP, Noyez L, Wouters C, Brouwer RM. Preoperative prediction of prolonged stay in the intensive care unit for coronary bypass surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25(2):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2003.11.005

16. Nilsson J, Algotsson L, Hoglund P, Luhrs C, Brandt J. EuroSCORE predicts intensive care unit stay and costs of open heart surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(5):1528-1534. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.060

17. Ghotkar SV, Grayson AD, Fabri BM, Dihmis WC, Pullan DM. Preoperative calculation of risk for prolonged intensive care unit stay following coronary artery bypass grafting. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;1:14. doi:10.1186/1749-8090-1-1418. Messaoudi N, Decocker J, Stockman BA, Bossaert LL, Rodrigus IE. Is EuroSCORE useful in the prediction of extended intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery? Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2009;36(1):35-39. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.02.007

19. Ettema RG, Peelen LM, Schuurmans MJ, Nierich AP, Kalkman CJ, Moons KG. Prediction models for prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery: systematic review and validation study. Circulation. 2010;122(7):682-689. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.926808

20. Engoren M. Does erythrocyte blood transfusion prevent acute kidney injury? Propensity-matched case control analysis. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(5):1126-1133. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e181f70f56

21. UK National Centre for Research Methods. Minimising the effect of missing data. Revised July 22, 2011. Accessed June 28, 2022. www.restore.ac.uk/srme/www/fac/soc/wie/research-new/srme/modules/mod3/9/index.html.

22. Leontyev S, Davierwala PM, Gaube LM, et al. Outcomes of dialysis-dependent patients after cardiac operations in a single-center experience of 483 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):1270-1276. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.07.05223. Freundlich RE, Maile MD, Sferra JJ, Jewell ES, Kheterpal S, Engoren M. Complications associated with mortality in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Database. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(1):55-62. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000002799

24. Freundlich RE, Maile MD, Hajjar MM, et al. Years of life lost after complications of coronary artery bypass operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(6):1893-1899. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.048

25. Koch CG, Li L, Sessler DI, et al. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(12):1229-1239. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa070403

26. Truche AS, Ragey SP, Souweine B, et al. ICU survival and need of renal replacement therapy with respect to AKI duration in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):127. doi:10.1186/s13613-018-0467-6

27. Kollef MH, Shapiro SD, Silver P, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of protocol-directed versus physician-directed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(4):567-574. doi:10.1097/00003246-199704000-00004

28. McWilliams D, Weblin J, Atkins G, et al. Enhancing rehabilitation of mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit: a quality improvement project. J Crit Care. 2015;30(1):13-18. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.09.018

29. Hernandez G, Vaquero C, Gonzalez P, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1354-1361. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2711

30. Schwann TA, Ramira PS, Engoren MC, et al. Evidence and temporality of the obesity paradox in coronary bypass surgery: an analysis of cause-specific mortality. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;54(5):896-903. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezy207

1. Ryan TA, Rady MY, Bashour A, Leventhal M, Lytle B, Starr NJ. Predictors of outcome in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care stay. Chest. 1997;112(4):1035-1042. doi:10.1378/chest.112.4.1035

2. Hein OV, Birnbaum J, Wernecke K, England M, Konertz W, Spies C. Prolonged intensive care unit stay in cardiac surgery: risk factors and long-term-survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(3):880-885. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.09.077

3. Mahesh B, Choong CK, Goldsmith K, Gerrard C, Nashef SA, Vuylsteke A. Prolonged stay in intensive care unit is a powerful predictor of adverse outcomes after cardiac operations. Ann Thoracic Surg. 2012;94(1):109-116. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.02.010

4. Silberman S, Bitran D, Fink D, Tauber R, Merin O. Very prolonged stay in the intensive care unit after cardiac operations: early results and late survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(1):15-21. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.01.103

5. Lapar DJ, Gillen JR, Crosby IK, et al. Predictors of operative mortality in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care unit duration. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(6):1116-1123. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.02.028

6. Manji RA, Arora RC, Singal RK, et al. Long-term outcome and predictors of noninstitutionalized survival subsequent to prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgical procedures. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(1):56-63. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.07.004

7. Augustin P, Tanaka S, Chhor V, et al. Prognosis of prolonged intensive care unit stay after aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis in octogenarians. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30(6):1555-1561. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2016.07.029

8. Yu PJ, Cassiere HA, Fishbein J, Esposito RA, Hartman AR. Outcomes of patients with prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30(6):1550-1554. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2016.03.145

9. Bashour CA, Yared JP, Ryan TA, et al. Long-term survival and functional capacity in cardiac surgery patients after prolonged intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(12):3847-3853. doi:10.1097/00003246-200012000-00018

10. Isgro F, Skuras JA, Kiessling AH, Lehmann A, Saggau W. Survival and quality of life after a long-term intensive care stay. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;50(2):95-99. doi:10.1055/s-2002-26693

11. Williams MR, Wellner RB, Hartnett EA, Hartnett EA, Thornton B, Kavarana MN, Mahapatra R, Oz MC Sladen R. Long-term survival and quality of life in cardiac surgical patients with prolonged intensive care unit length of stay. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73(5):1472-1478.

12. Lagercrantz E, Lindblom D, Sartipy U. Survival and quality of life in cardiac surgery patients with prolonged intensive care. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:490-495. doi:10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03464-1

13. Edwards FH, Clark RE, Schwartz M. Coronary artery bypass grafting: the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57(1):12-19. doi:10.1016/0003-4975(94)90358-1

14. Lawrence DR, Valencia O, Smith EE, Murday A, Treasure T. Parsonnet score is a good predictor of the duration of intensive care unit stay following cardiac surgery. Heart. 2000;83(4):429-432. doi:10.1136/heart.83.4.429

15. Janssen DP, Noyez L, Wouters C, Brouwer RM. Preoperative prediction of prolonged stay in the intensive care unit for coronary bypass surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25(2):203-207. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2003.11.005

16. Nilsson J, Algotsson L, Hoglund P, Luhrs C, Brandt J. EuroSCORE predicts intensive care unit stay and costs of open heart surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78(5):1528-1534. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.060

17. Ghotkar SV, Grayson AD, Fabri BM, Dihmis WC, Pullan DM. Preoperative calculation of risk for prolonged intensive care unit stay following coronary artery bypass grafting. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;1:14. doi:10.1186/1749-8090-1-1418. Messaoudi N, Decocker J, Stockman BA, Bossaert LL, Rodrigus IE. Is EuroSCORE useful in the prediction of extended intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery? Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2009;36(1):35-39. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.02.007

19. Ettema RG, Peelen LM, Schuurmans MJ, Nierich AP, Kalkman CJ, Moons KG. Prediction models for prolonged intensive care unit stay after cardiac surgery: systematic review and validation study. Circulation. 2010;122(7):682-689. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.926808

20. Engoren M. Does erythrocyte blood transfusion prevent acute kidney injury? Propensity-matched case control analysis. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(5):1126-1133. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e181f70f56

21. UK National Centre for Research Methods. Minimising the effect of missing data. Revised July 22, 2011. Accessed June 28, 2022. www.restore.ac.uk/srme/www/fac/soc/wie/research-new/srme/modules/mod3/9/index.html.

22. Leontyev S, Davierwala PM, Gaube LM, et al. Outcomes of dialysis-dependent patients after cardiac operations in a single-center experience of 483 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(4):1270-1276. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.07.05223. Freundlich RE, Maile MD, Sferra JJ, Jewell ES, Kheterpal S, Engoren M. Complications associated with mortality in the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Database. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(1):55-62. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000002799

24. Freundlich RE, Maile MD, Hajjar MM, et al. Years of life lost after complications of coronary artery bypass operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103(6):1893-1899. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.09.048

25. Koch CG, Li L, Sessler DI, et al. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(12):1229-1239. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa070403

26. Truche AS, Ragey SP, Souweine B, et al. ICU survival and need of renal replacement therapy with respect to AKI duration in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):127. doi:10.1186/s13613-018-0467-6

27. Kollef MH, Shapiro SD, Silver P, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of protocol-directed versus physician-directed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(4):567-574. doi:10.1097/00003246-199704000-00004

28. McWilliams D, Weblin J, Atkins G, et al. Enhancing rehabilitation of mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit: a quality improvement project. J Crit Care. 2015;30(1):13-18. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2014.09.018

29. Hernandez G, Vaquero C, Gonzalez P, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1354-1361. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2711

30. Schwann TA, Ramira PS, Engoren MC, et al. Evidence and temporality of the obesity paradox in coronary bypass surgery: an analysis of cause-specific mortality. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;54(5):896-903. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezy207