User login

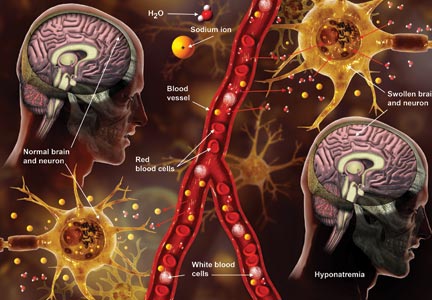

Q) A clinic patient of mine was recently admitted to the hospital with hyponatremia (serum sodium, 115 mEq/L). She was treated with 2 L of normal saline and discharged home 48 hours later, at her baseline mental status with a serum sodium level of 132 mEq/L. Two days later, she was readmitted for mental status changes, and MRI showed brain swelling. The neurologist stated this was a result of the initial treatment for her hyponatremia. How is this possible?

The cause-and-effect relationship between rapid correction of chronic hyponatremia and subsequent development of neurologic problems was discovered in the late 1970s. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis (known as osmotic demyelination syndrome or ODS) is a neurologic condition that can occur from rapid sodium correction. It is diagnosed by MRI, which shows hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted images. Clinical signs include upper motor neuron signs, pseudobulbar palsy, spastic quadriparesis, and mental status changes ranging from mild confusion to coma.2

Treatment for hyponatremia should be guided by symptom management.2,3 If a patient is asymptomatic, a simple and effective strategy is to keep NPO for 24 hours, except for medications. Simple food and fluid restriction will likely increase the serum sodium level because of obligate solute losses and urinary electrolyte free water loss.2,4 While the first instinct is to feed these patients, as they often appear malnourished, this can cause a solute load leading to a too-rapid sodium correction. After 24 hours, if intake restriction is not effective, use 0.5% normal saline but with limited dosing orders, as usual saline dosing can cause too rapid a correction.2

For symptomatic patients (confusion, seizures, coma), the goal is to initially elevate sodium by 1 to 2 mEq/L per hour for the first two to three hours. Do not exceed 10 mEq/L in 24 hours or 18 mEq/L in 48 hours. Exceeding these limits puts patients at high risk for ODS. In fact, even when staying within these parameters, there is some risk for overcorrection. It is always better to go slowly.2,3

In the patient with hyponatremia due to low solute intake (eg, beer potomania), diuresis can start spontaneously after a period of food and fluid restriction. It can also be initiated with just a small amount of solute. For example, administering an IV antibiotic with a base solution of 100 mL of normal saline or a “banana bag” (an IV solution containing 0.5 to 1 L of normal saline with multivitamins/minerals that cause the fluid to be yellow) can produce several liters of diuresis.2 Once you open the floodgate, you can unintentionally cause too-rapid correction that could lead to ODS.

In chronic hyponatremic patients, low antidiuretic hormone (ADH) levels are often found; thus when a solute is introduced, there is little ADH in the system to protect against excessive water loss and electrolyte imbalance. At the same time, excessive water loss can translate to higher sodium levels and increase the risk for cerebral edema. If rapid diuresis occurs, an infusion of D5W (5% dextrose in water) to match the rate of urine output may prevent a rapid serum sodium level rise. Frequent monitoring of serum sodium levels is often necessary. In instances where ODS is already present, there are case studies of improved neurologic outcomes with reduction of serum sodium levels.2,3

While the treatment of hyponatremia at first glance seems straightforward—replace that which is lost—it can actually transform a seemingly simple problem into a complicated clinical course requiring intensive care, due to the need for frequent monitoring and intervention.

Kristina Unterseher, MSN, FNP, CNN-NP

Peacehealth St. John

Medical Center

Longview, WA

REFERENCES

1. Hilden T, Swensen TL. Electrolyte disturbances in beer drinkers: a specific “hypo-osmolaity syndrome.” Lancet. 1975;2(7928):245-246.

2. Sanghvi SR, Kellerman PS, Nanovic L. Beer potomania: an unusual cause of hyponatremia at high risk of complications from rapid correction. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50(4):673-680.

3. Bhattarai N, Poonam K, Panda M. Beer potomania: a case report. BMJ Case Rep. 2010; 2010: bcr10.2009.2414.

4. Campbell M. Hyponatremia and central pontine myelinolysis as a result of beer potomania: a case report. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(4):PCC.09100936.

5. Thaler SM, Teitelbaum I, Beri T. “Beer potomania” in non-beer drinkers: effect of low dietary solute intake. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31(6):1028-1031.

Q) A clinic patient of mine was recently admitted to the hospital with hyponatremia (serum sodium, 115 mEq/L). She was treated with 2 L of normal saline and discharged home 48 hours later, at her baseline mental status with a serum sodium level of 132 mEq/L. Two days later, she was readmitted for mental status changes, and MRI showed brain swelling. The neurologist stated this was a result of the initial treatment for her hyponatremia. How is this possible?

The cause-and-effect relationship between rapid correction of chronic hyponatremia and subsequent development of neurologic problems was discovered in the late 1970s. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis (known as osmotic demyelination syndrome or ODS) is a neurologic condition that can occur from rapid sodium correction. It is diagnosed by MRI, which shows hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted images. Clinical signs include upper motor neuron signs, pseudobulbar palsy, spastic quadriparesis, and mental status changes ranging from mild confusion to coma.2

Treatment for hyponatremia should be guided by symptom management.2,3 If a patient is asymptomatic, a simple and effective strategy is to keep NPO for 24 hours, except for medications. Simple food and fluid restriction will likely increase the serum sodium level because of obligate solute losses and urinary electrolyte free water loss.2,4 While the first instinct is to feed these patients, as they often appear malnourished, this can cause a solute load leading to a too-rapid sodium correction. After 24 hours, if intake restriction is not effective, use 0.5% normal saline but with limited dosing orders, as usual saline dosing can cause too rapid a correction.2

For symptomatic patients (confusion, seizures, coma), the goal is to initially elevate sodium by 1 to 2 mEq/L per hour for the first two to three hours. Do not exceed 10 mEq/L in 24 hours or 18 mEq/L in 48 hours. Exceeding these limits puts patients at high risk for ODS. In fact, even when staying within these parameters, there is some risk for overcorrection. It is always better to go slowly.2,3

In the patient with hyponatremia due to low solute intake (eg, beer potomania), diuresis can start spontaneously after a period of food and fluid restriction. It can also be initiated with just a small amount of solute. For example, administering an IV antibiotic with a base solution of 100 mL of normal saline or a “banana bag” (an IV solution containing 0.5 to 1 L of normal saline with multivitamins/minerals that cause the fluid to be yellow) can produce several liters of diuresis.2 Once you open the floodgate, you can unintentionally cause too-rapid correction that could lead to ODS.

In chronic hyponatremic patients, low antidiuretic hormone (ADH) levels are often found; thus when a solute is introduced, there is little ADH in the system to protect against excessive water loss and electrolyte imbalance. At the same time, excessive water loss can translate to higher sodium levels and increase the risk for cerebral edema. If rapid diuresis occurs, an infusion of D5W (5% dextrose in water) to match the rate of urine output may prevent a rapid serum sodium level rise. Frequent monitoring of serum sodium levels is often necessary. In instances where ODS is already present, there are case studies of improved neurologic outcomes with reduction of serum sodium levels.2,3

While the treatment of hyponatremia at first glance seems straightforward—replace that which is lost—it can actually transform a seemingly simple problem into a complicated clinical course requiring intensive care, due to the need for frequent monitoring and intervention.

Kristina Unterseher, MSN, FNP, CNN-NP

Peacehealth St. John

Medical Center

Longview, WA

REFERENCES

1. Hilden T, Swensen TL. Electrolyte disturbances in beer drinkers: a specific “hypo-osmolaity syndrome.” Lancet. 1975;2(7928):245-246.

2. Sanghvi SR, Kellerman PS, Nanovic L. Beer potomania: an unusual cause of hyponatremia at high risk of complications from rapid correction. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50(4):673-680.

3. Bhattarai N, Poonam K, Panda M. Beer potomania: a case report. BMJ Case Rep. 2010; 2010: bcr10.2009.2414.

4. Campbell M. Hyponatremia and central pontine myelinolysis as a result of beer potomania: a case report. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(4):PCC.09100936.

5. Thaler SM, Teitelbaum I, Beri T. “Beer potomania” in non-beer drinkers: effect of low dietary solute intake. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31(6):1028-1031.

Q) A clinic patient of mine was recently admitted to the hospital with hyponatremia (serum sodium, 115 mEq/L). She was treated with 2 L of normal saline and discharged home 48 hours later, at her baseline mental status with a serum sodium level of 132 mEq/L. Two days later, she was readmitted for mental status changes, and MRI showed brain swelling. The neurologist stated this was a result of the initial treatment for her hyponatremia. How is this possible?

The cause-and-effect relationship between rapid correction of chronic hyponatremia and subsequent development of neurologic problems was discovered in the late 1970s. Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis (known as osmotic demyelination syndrome or ODS) is a neurologic condition that can occur from rapid sodium correction. It is diagnosed by MRI, which shows hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted images. Clinical signs include upper motor neuron signs, pseudobulbar palsy, spastic quadriparesis, and mental status changes ranging from mild confusion to coma.2

Treatment for hyponatremia should be guided by symptom management.2,3 If a patient is asymptomatic, a simple and effective strategy is to keep NPO for 24 hours, except for medications. Simple food and fluid restriction will likely increase the serum sodium level because of obligate solute losses and urinary electrolyte free water loss.2,4 While the first instinct is to feed these patients, as they often appear malnourished, this can cause a solute load leading to a too-rapid sodium correction. After 24 hours, if intake restriction is not effective, use 0.5% normal saline but with limited dosing orders, as usual saline dosing can cause too rapid a correction.2

For symptomatic patients (confusion, seizures, coma), the goal is to initially elevate sodium by 1 to 2 mEq/L per hour for the first two to three hours. Do not exceed 10 mEq/L in 24 hours or 18 mEq/L in 48 hours. Exceeding these limits puts patients at high risk for ODS. In fact, even when staying within these parameters, there is some risk for overcorrection. It is always better to go slowly.2,3

In the patient with hyponatremia due to low solute intake (eg, beer potomania), diuresis can start spontaneously after a period of food and fluid restriction. It can also be initiated with just a small amount of solute. For example, administering an IV antibiotic with a base solution of 100 mL of normal saline or a “banana bag” (an IV solution containing 0.5 to 1 L of normal saline with multivitamins/minerals that cause the fluid to be yellow) can produce several liters of diuresis.2 Once you open the floodgate, you can unintentionally cause too-rapid correction that could lead to ODS.

In chronic hyponatremic patients, low antidiuretic hormone (ADH) levels are often found; thus when a solute is introduced, there is little ADH in the system to protect against excessive water loss and electrolyte imbalance. At the same time, excessive water loss can translate to higher sodium levels and increase the risk for cerebral edema. If rapid diuresis occurs, an infusion of D5W (5% dextrose in water) to match the rate of urine output may prevent a rapid serum sodium level rise. Frequent monitoring of serum sodium levels is often necessary. In instances where ODS is already present, there are case studies of improved neurologic outcomes with reduction of serum sodium levels.2,3

While the treatment of hyponatremia at first glance seems straightforward—replace that which is lost—it can actually transform a seemingly simple problem into a complicated clinical course requiring intensive care, due to the need for frequent monitoring and intervention.

Kristina Unterseher, MSN, FNP, CNN-NP

Peacehealth St. John

Medical Center

Longview, WA

REFERENCES

1. Hilden T, Swensen TL. Electrolyte disturbances in beer drinkers: a specific “hypo-osmolaity syndrome.” Lancet. 1975;2(7928):245-246.

2. Sanghvi SR, Kellerman PS, Nanovic L. Beer potomania: an unusual cause of hyponatremia at high risk of complications from rapid correction. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50(4):673-680.

3. Bhattarai N, Poonam K, Panda M. Beer potomania: a case report. BMJ Case Rep. 2010; 2010: bcr10.2009.2414.

4. Campbell M. Hyponatremia and central pontine myelinolysis as a result of beer potomania: a case report. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(4):PCC.09100936.

5. Thaler SM, Teitelbaum I, Beri T. “Beer potomania” in non-beer drinkers: effect of low dietary solute intake. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31(6):1028-1031.