User login

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 26-YEAR-OLD MAN came into the emergency department for treatment of vomiting, and pain in his abdomen and right shoulder. His vital signs were normal, with the exception of his heart rate, which was 109 bpm. His oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. The patient, a smoker, did not complain of any difficulty breathing, despite having diminished breath sounds over the left lung fields and absent breath sounds over the right. The rest of the exam was normal.

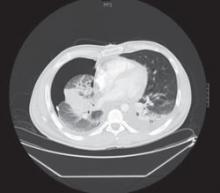

The patient’s initial blood work was within normal limits. We ordered a chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) and a chest computed tomography (CT) scan to further assess his decreased breath sounds.

FIGURE 1

A revealing X-ray

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU MANAGE THIS CONDITION?

Diagnosis: Adenocarcinoma

The chest x-ray revealed a massive right-sided pleural effusion resulting in a hemothorax, tense mediastinum, and partial collapse of the left lung. A CT scan (FIGURE 2) of the chest revealed a 5-cm mass in the right lung. Thoracocentesis was performed and 11 liters of pleural fluid were removed.

Cytological examination of the pleural fluid revealed adenocarcinoma of the lung. A diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of pulmonary origin was supported by immunohistochemical tests that were positive for thyroid transcription factor 1, cytokeratin 7, carcinoembryonic antigen, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which made findings from other sites of adenocarcinoma less likely. A bone scan revealed metastases to the sixth rib and sternum, indicating stage IV adenocarcinoma (FIGURE 3).

FIGURE 2

Mass in lung

FIGURE 3

Bone scan reveals metastases

A cancer that presents at advanced stages

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States in both men and women. The National Cancer Institute estimates that 159,390 people will die of lung cancer this year.1

More than 219,000 cases of lung cancer will be diagnosed this year;1 primary adenocarcinoma, a subtype of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), is the most commonly diagnosed form of lung cancer.2 Most NSCLC cases will present at advanced stages, which limits treatment options and leads to a poor prognosis.

Cigarette smoking remains the most significant risk factor for lung cancer and, according to the American Cancer Society, smoking is responsible for at least 30% of all cancer deaths.3 Moreover, the US Department of Health and Human Services has found that 80% of lung cancers are attributable to smoking.4

What was unusual here? Although our patient had a 16-pack-year history of smoking, it is unusual for the disease to present in adolescents and young adults. The youngest reported case of primary adenocarcinoma of the lung involved a 15 year old, leading researchers to believe that genetic mutation may play a role. In addition, researchers have identified a mutation involving the EGFR gene that may predispose an individual to developing NSCLC.5 Trials are now underway using tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as gefitinib and erlotinib, to target the tyrosine kinase domain on EGFR.6,7

Differential Dx includes a variety of infections

The differential diagnosis of a lung mass is broad and includes bacterial, fungal, pneumocystic, and granulomatous infections. Cancer, connective tissue diseases, and vascular malformations may also present in this manner. However, our patient also had a pleural effusion, which would lead one to consider cancer or a bacterial infection as a more likely etiology.

In a 26-year-old man, the most common metastatic cancers would include testicular, melanoma, and thyroid cancers. In addition, the typical pattern of metastatic disease of these cancers on chest x-ray is that of bilateral, multiple, round, and well-circumscribed lesions, which was not the case with our patient.

Pleural fluid analysis holds key to diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of lung cancer—particularly in a younger population—requires a high level of suspicion. A delay in diagnosis leads to a poor prognosis. Symptoms and clinical findings should direct the diagnostic process.

In our patient, the diagnosis was particularly challenging because he had no presenting pulmonary symptoms and the work-up was directed by findings on exam. Pleural effusions are present in up to one-third of patients with NSCLC at the time of presentation,8 as was the case with our patient. Analysis of pleural fluid or tissue is required to confirm the diagnosis of NSCLC.

Surgery? Chemo? What’s best and when

Most (55%) NSCLC patients present at advanced stages,1 limiting recommended treatment options. Treatment and management considerations are as follows:

Surgical resection is considered the treatment of choice for patients with local disease if pulmonary function is adequate and comorbidities do not preclude surgery (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B).9

Radical radiotherapy may be considered as a primary treatment modality for patients who refuse surgery or those with comorbid conditions that preclude safe resection (SOR: C).10

Platinum-based combination chemotherapy may be used as a first-line therapy to prolong survival in patients with advanced disease (SOR: B).11

Surgery wasn’t an option for our patient

Through pleural fluid analysis, we confirmed our patient’s diagnosis of primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma. A subsequent bone scan (FIGURE 3) showed metastases to the sixth rib and sternum, indicating that he had stage IV pulmonary adenocarcinoma.

Due to this advanced stage, surgery was not practical. The patient’s oncologist started him on 2 chemotherapy agents, cisplatin and paclitaxel.

The 5-year survival rate with treatment for patients with advanced stage pulmonary adenocarcinoma is approximately 1%.12 Our patient was expected to live another 9 to 12 months.

CORRESPONDENCE Robert Garcia, MD, Associate Director, Family Medicine Residency Program, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, 2927 N. 7th Avenue, Phoenix, AZ 85013; [email protected]

1. National Cancer Institute. Surveillance epidemiology and end results (SEER) stat fact sheet. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html. Accessed August 27, 2009.

2. Homer MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, et al (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2006, National Cancer Institute. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/results_merged/sect_15_lung_bronchus.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2009.

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2009. Page 47. Available at: www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/500809web.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2009.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Ga: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health; 2004.

5. Sharma SV, Gajowniczek P, Way IP, et al. A common signaling cascade may underlie “addiction” to the Src, BCR-ABL, and EGF receptor oncogenes. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:425-435.

6. Inoue A, Suzuki T, Fukuhara T, et al. Prospective phase II study of gefitinib for chemotherapy-naïve patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3340-3346.

7. Paz-Ares L, Sanchez JM, Garcia-Velasco A, et al. A prospective phase II trial of erlotinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (p) with mutations in the tyrosine kinase (TK) domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Paper presented at the 2006 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; June 2-6, 2006; Atlanta, Ga.

8. The American Thoracic Society and The European Respiratory Society. Pretreatment evaluation of non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 1997;156:320-332.

9. Manser R, Wright G, Byrnes G, et al. Surgery for early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD004699.-

10. Rowell NP, Williams CJ. Radical radiotherapy for stage I/II non-small cell lung cancer in patients not sufficiently fit for or declining surgery (medically inoperable): a systematic review. Thorax. 2001;56:628-638.

11. Pfister DG, Johnson DH, Azzoli CG, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology treatment of unresectable non-small cell lung cancer guideline: update 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:330-353.

12. Lung carcinoma: tumors of the lungs. Merck Manual Professional Edition. Available at: http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec05/ch062/ch062b.html#. Accessed August 27, 2009.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 26-YEAR-OLD MAN came into the emergency department for treatment of vomiting, and pain in his abdomen and right shoulder. His vital signs were normal, with the exception of his heart rate, which was 109 bpm. His oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. The patient, a smoker, did not complain of any difficulty breathing, despite having diminished breath sounds over the left lung fields and absent breath sounds over the right. The rest of the exam was normal.

The patient’s initial blood work was within normal limits. We ordered a chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) and a chest computed tomography (CT) scan to further assess his decreased breath sounds.

FIGURE 1

A revealing X-ray

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU MANAGE THIS CONDITION?

Diagnosis: Adenocarcinoma

The chest x-ray revealed a massive right-sided pleural effusion resulting in a hemothorax, tense mediastinum, and partial collapse of the left lung. A CT scan (FIGURE 2) of the chest revealed a 5-cm mass in the right lung. Thoracocentesis was performed and 11 liters of pleural fluid were removed.

Cytological examination of the pleural fluid revealed adenocarcinoma of the lung. A diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of pulmonary origin was supported by immunohistochemical tests that were positive for thyroid transcription factor 1, cytokeratin 7, carcinoembryonic antigen, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which made findings from other sites of adenocarcinoma less likely. A bone scan revealed metastases to the sixth rib and sternum, indicating stage IV adenocarcinoma (FIGURE 3).

FIGURE 2

Mass in lung

FIGURE 3

Bone scan reveals metastases

A cancer that presents at advanced stages

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States in both men and women. The National Cancer Institute estimates that 159,390 people will die of lung cancer this year.1

More than 219,000 cases of lung cancer will be diagnosed this year;1 primary adenocarcinoma, a subtype of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), is the most commonly diagnosed form of lung cancer.2 Most NSCLC cases will present at advanced stages, which limits treatment options and leads to a poor prognosis.

Cigarette smoking remains the most significant risk factor for lung cancer and, according to the American Cancer Society, smoking is responsible for at least 30% of all cancer deaths.3 Moreover, the US Department of Health and Human Services has found that 80% of lung cancers are attributable to smoking.4

What was unusual here? Although our patient had a 16-pack-year history of smoking, it is unusual for the disease to present in adolescents and young adults. The youngest reported case of primary adenocarcinoma of the lung involved a 15 year old, leading researchers to believe that genetic mutation may play a role. In addition, researchers have identified a mutation involving the EGFR gene that may predispose an individual to developing NSCLC.5 Trials are now underway using tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as gefitinib and erlotinib, to target the tyrosine kinase domain on EGFR.6,7

Differential Dx includes a variety of infections

The differential diagnosis of a lung mass is broad and includes bacterial, fungal, pneumocystic, and granulomatous infections. Cancer, connective tissue diseases, and vascular malformations may also present in this manner. However, our patient also had a pleural effusion, which would lead one to consider cancer or a bacterial infection as a more likely etiology.

In a 26-year-old man, the most common metastatic cancers would include testicular, melanoma, and thyroid cancers. In addition, the typical pattern of metastatic disease of these cancers on chest x-ray is that of bilateral, multiple, round, and well-circumscribed lesions, which was not the case with our patient.

Pleural fluid analysis holds key to diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of lung cancer—particularly in a younger population—requires a high level of suspicion. A delay in diagnosis leads to a poor prognosis. Symptoms and clinical findings should direct the diagnostic process.

In our patient, the diagnosis was particularly challenging because he had no presenting pulmonary symptoms and the work-up was directed by findings on exam. Pleural effusions are present in up to one-third of patients with NSCLC at the time of presentation,8 as was the case with our patient. Analysis of pleural fluid or tissue is required to confirm the diagnosis of NSCLC.

Surgery? Chemo? What’s best and when

Most (55%) NSCLC patients present at advanced stages,1 limiting recommended treatment options. Treatment and management considerations are as follows:

Surgical resection is considered the treatment of choice for patients with local disease if pulmonary function is adequate and comorbidities do not preclude surgery (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B).9

Radical radiotherapy may be considered as a primary treatment modality for patients who refuse surgery or those with comorbid conditions that preclude safe resection (SOR: C).10

Platinum-based combination chemotherapy may be used as a first-line therapy to prolong survival in patients with advanced disease (SOR: B).11

Surgery wasn’t an option for our patient

Through pleural fluid analysis, we confirmed our patient’s diagnosis of primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma. A subsequent bone scan (FIGURE 3) showed metastases to the sixth rib and sternum, indicating that he had stage IV pulmonary adenocarcinoma.

Due to this advanced stage, surgery was not practical. The patient’s oncologist started him on 2 chemotherapy agents, cisplatin and paclitaxel.

The 5-year survival rate with treatment for patients with advanced stage pulmonary adenocarcinoma is approximately 1%.12 Our patient was expected to live another 9 to 12 months.

CORRESPONDENCE Robert Garcia, MD, Associate Director, Family Medicine Residency Program, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, 2927 N. 7th Avenue, Phoenix, AZ 85013; [email protected]

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

A 26-YEAR-OLD MAN came into the emergency department for treatment of vomiting, and pain in his abdomen and right shoulder. His vital signs were normal, with the exception of his heart rate, which was 109 bpm. His oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. The patient, a smoker, did not complain of any difficulty breathing, despite having diminished breath sounds over the left lung fields and absent breath sounds over the right. The rest of the exam was normal.

The patient’s initial blood work was within normal limits. We ordered a chest x-ray (FIGURE 1) and a chest computed tomography (CT) scan to further assess his decreased breath sounds.

FIGURE 1

A revealing X-ray

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU MANAGE THIS CONDITION?

Diagnosis: Adenocarcinoma

The chest x-ray revealed a massive right-sided pleural effusion resulting in a hemothorax, tense mediastinum, and partial collapse of the left lung. A CT scan (FIGURE 2) of the chest revealed a 5-cm mass in the right lung. Thoracocentesis was performed and 11 liters of pleural fluid were removed.

Cytological examination of the pleural fluid revealed adenocarcinoma of the lung. A diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of pulmonary origin was supported by immunohistochemical tests that were positive for thyroid transcription factor 1, cytokeratin 7, carcinoembryonic antigen, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), which made findings from other sites of adenocarcinoma less likely. A bone scan revealed metastases to the sixth rib and sternum, indicating stage IV adenocarcinoma (FIGURE 3).

FIGURE 2

Mass in lung

FIGURE 3

Bone scan reveals metastases

A cancer that presents at advanced stages

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States in both men and women. The National Cancer Institute estimates that 159,390 people will die of lung cancer this year.1

More than 219,000 cases of lung cancer will be diagnosed this year;1 primary adenocarcinoma, a subtype of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), is the most commonly diagnosed form of lung cancer.2 Most NSCLC cases will present at advanced stages, which limits treatment options and leads to a poor prognosis.

Cigarette smoking remains the most significant risk factor for lung cancer and, according to the American Cancer Society, smoking is responsible for at least 30% of all cancer deaths.3 Moreover, the US Department of Health and Human Services has found that 80% of lung cancers are attributable to smoking.4

What was unusual here? Although our patient had a 16-pack-year history of smoking, it is unusual for the disease to present in adolescents and young adults. The youngest reported case of primary adenocarcinoma of the lung involved a 15 year old, leading researchers to believe that genetic mutation may play a role. In addition, researchers have identified a mutation involving the EGFR gene that may predispose an individual to developing NSCLC.5 Trials are now underway using tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as gefitinib and erlotinib, to target the tyrosine kinase domain on EGFR.6,7

Differential Dx includes a variety of infections

The differential diagnosis of a lung mass is broad and includes bacterial, fungal, pneumocystic, and granulomatous infections. Cancer, connective tissue diseases, and vascular malformations may also present in this manner. However, our patient also had a pleural effusion, which would lead one to consider cancer or a bacterial infection as a more likely etiology.

In a 26-year-old man, the most common metastatic cancers would include testicular, melanoma, and thyroid cancers. In addition, the typical pattern of metastatic disease of these cancers on chest x-ray is that of bilateral, multiple, round, and well-circumscribed lesions, which was not the case with our patient.

Pleural fluid analysis holds key to diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of lung cancer—particularly in a younger population—requires a high level of suspicion. A delay in diagnosis leads to a poor prognosis. Symptoms and clinical findings should direct the diagnostic process.

In our patient, the diagnosis was particularly challenging because he had no presenting pulmonary symptoms and the work-up was directed by findings on exam. Pleural effusions are present in up to one-third of patients with NSCLC at the time of presentation,8 as was the case with our patient. Analysis of pleural fluid or tissue is required to confirm the diagnosis of NSCLC.

Surgery? Chemo? What’s best and when

Most (55%) NSCLC patients present at advanced stages,1 limiting recommended treatment options. Treatment and management considerations are as follows:

Surgical resection is considered the treatment of choice for patients with local disease if pulmonary function is adequate and comorbidities do not preclude surgery (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B).9

Radical radiotherapy may be considered as a primary treatment modality for patients who refuse surgery or those with comorbid conditions that preclude safe resection (SOR: C).10

Platinum-based combination chemotherapy may be used as a first-line therapy to prolong survival in patients with advanced disease (SOR: B).11

Surgery wasn’t an option for our patient

Through pleural fluid analysis, we confirmed our patient’s diagnosis of primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma. A subsequent bone scan (FIGURE 3) showed metastases to the sixth rib and sternum, indicating that he had stage IV pulmonary adenocarcinoma.

Due to this advanced stage, surgery was not practical. The patient’s oncologist started him on 2 chemotherapy agents, cisplatin and paclitaxel.

The 5-year survival rate with treatment for patients with advanced stage pulmonary adenocarcinoma is approximately 1%.12 Our patient was expected to live another 9 to 12 months.

CORRESPONDENCE Robert Garcia, MD, Associate Director, Family Medicine Residency Program, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, 2927 N. 7th Avenue, Phoenix, AZ 85013; [email protected]

1. National Cancer Institute. Surveillance epidemiology and end results (SEER) stat fact sheet. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html. Accessed August 27, 2009.

2. Homer MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, et al (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2006, National Cancer Institute. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/results_merged/sect_15_lung_bronchus.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2009.

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2009. Page 47. Available at: www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/500809web.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2009.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Ga: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health; 2004.

5. Sharma SV, Gajowniczek P, Way IP, et al. A common signaling cascade may underlie “addiction” to the Src, BCR-ABL, and EGF receptor oncogenes. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:425-435.

6. Inoue A, Suzuki T, Fukuhara T, et al. Prospective phase II study of gefitinib for chemotherapy-naïve patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3340-3346.

7. Paz-Ares L, Sanchez JM, Garcia-Velasco A, et al. A prospective phase II trial of erlotinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (p) with mutations in the tyrosine kinase (TK) domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Paper presented at the 2006 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; June 2-6, 2006; Atlanta, Ga.

8. The American Thoracic Society and The European Respiratory Society. Pretreatment evaluation of non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 1997;156:320-332.

9. Manser R, Wright G, Byrnes G, et al. Surgery for early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD004699.-

10. Rowell NP, Williams CJ. Radical radiotherapy for stage I/II non-small cell lung cancer in patients not sufficiently fit for or declining surgery (medically inoperable): a systematic review. Thorax. 2001;56:628-638.

11. Pfister DG, Johnson DH, Azzoli CG, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology treatment of unresectable non-small cell lung cancer guideline: update 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:330-353.

12. Lung carcinoma: tumors of the lungs. Merck Manual Professional Edition. Available at: http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec05/ch062/ch062b.html#. Accessed August 27, 2009.

1. National Cancer Institute. Surveillance epidemiology and end results (SEER) stat fact sheet. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html. Accessed August 27, 2009.

2. Homer MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, et al (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2006, National Cancer Institute. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/results_merged/sect_15_lung_bronchus.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2009.

3. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2009. Page 47. Available at: www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/500809web.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2009.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Ga: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health; 2004.

5. Sharma SV, Gajowniczek P, Way IP, et al. A common signaling cascade may underlie “addiction” to the Src, BCR-ABL, and EGF receptor oncogenes. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:425-435.

6. Inoue A, Suzuki T, Fukuhara T, et al. Prospective phase II study of gefitinib for chemotherapy-naïve patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3340-3346.

7. Paz-Ares L, Sanchez JM, Garcia-Velasco A, et al. A prospective phase II trial of erlotinib in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (p) with mutations in the tyrosine kinase (TK) domain of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Paper presented at the 2006 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; June 2-6, 2006; Atlanta, Ga.

8. The American Thoracic Society and The European Respiratory Society. Pretreatment evaluation of non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 1997;156:320-332.

9. Manser R, Wright G, Byrnes G, et al. Surgery for early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD004699.-

10. Rowell NP, Williams CJ. Radical radiotherapy for stage I/II non-small cell lung cancer in patients not sufficiently fit for or declining surgery (medically inoperable): a systematic review. Thorax. 2001;56:628-638.

11. Pfister DG, Johnson DH, Azzoli CG, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology treatment of unresectable non-small cell lung cancer guideline: update 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:330-353.

12. Lung carcinoma: tumors of the lungs. Merck Manual Professional Edition. Available at: http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec05/ch062/ch062b.html#. Accessed August 27, 2009.