User login

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen striatus (choice “d”), a rare, self-limited condition usually seen on the extremities of children. It will be discussed further in the next section.

The differential for lichen striatus includes psoriasis (choice “a”). However, typical psoriatic lesions would not assume this configuration and would likely manifest with other corroborative areas of involvement.

Eczema (choice “b”) is certainly common in children, but it is unlikely to be relegated to one linear area. The same can be said of pityriasis rosea (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Lichen striatus, also known as Blaschko linear acquired skin inflammation, is an unusual self-limited condition of unknown etiology seen mostly on the extremities of children ages 3 to 10. More common on legs than on arms, it can occasionally appear on the face.

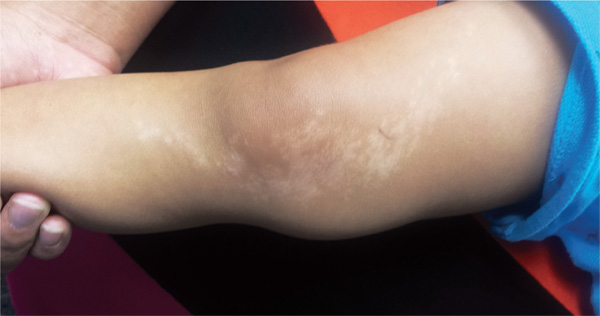

Its linear configuration is instantly diagnostic: The lesion typically follows the Blaschko lines, which represent a segmental clone of cutaneous cells deposited at an embryonic stage of development.

As seen in this case, postinflammatory hypopigmentation is common. In a minority of cases, the condition can involve the entire length of the extremity—even the digits, where it can lead to dystrophy of the affected nail. It almost always resolves within a few weeks to months, with or without treatment (which is limited to symptom relief).

Several potential causes of lichen striatus have been posited. The most convincing theory is a possible connection with human herpesviruses 6 and 7, which are also triggers for pityriasis rosea. There have been cases in which both conditions are present, producing somewhat similar microscopic changes in the skin (and both resolving without treatment). Additional items in the differential include lichen planus, lichen nitidus, and warts.

TREATMENT

For most cases of lichen striatus, treatment is supportive: topical steroids for the itching, which is seldom severe. Given the self-limited but prolonged nature of the problem, patient education is the more important component; these days, there are web-based sources to which you can direct your patients for reliable information, including the Mayo Clinic and the American Academy of Dermatology.

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen striatus (choice “d”), a rare, self-limited condition usually seen on the extremities of children. It will be discussed further in the next section.

The differential for lichen striatus includes psoriasis (choice “a”). However, typical psoriatic lesions would not assume this configuration and would likely manifest with other corroborative areas of involvement.

Eczema (choice “b”) is certainly common in children, but it is unlikely to be relegated to one linear area. The same can be said of pityriasis rosea (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Lichen striatus, also known as Blaschko linear acquired skin inflammation, is an unusual self-limited condition of unknown etiology seen mostly on the extremities of children ages 3 to 10. More common on legs than on arms, it can occasionally appear on the face.

Its linear configuration is instantly diagnostic: The lesion typically follows the Blaschko lines, which represent a segmental clone of cutaneous cells deposited at an embryonic stage of development.

As seen in this case, postinflammatory hypopigmentation is common. In a minority of cases, the condition can involve the entire length of the extremity—even the digits, where it can lead to dystrophy of the affected nail. It almost always resolves within a few weeks to months, with or without treatment (which is limited to symptom relief).

Several potential causes of lichen striatus have been posited. The most convincing theory is a possible connection with human herpesviruses 6 and 7, which are also triggers for pityriasis rosea. There have been cases in which both conditions are present, producing somewhat similar microscopic changes in the skin (and both resolving without treatment). Additional items in the differential include lichen planus, lichen nitidus, and warts.

TREATMENT

For most cases of lichen striatus, treatment is supportive: topical steroids for the itching, which is seldom severe. Given the self-limited but prolonged nature of the problem, patient education is the more important component; these days, there are web-based sources to which you can direct your patients for reliable information, including the Mayo Clinic and the American Academy of Dermatology.

ANSWER

The correct answer is lichen striatus (choice “d”), a rare, self-limited condition usually seen on the extremities of children. It will be discussed further in the next section.

The differential for lichen striatus includes psoriasis (choice “a”). However, typical psoriatic lesions would not assume this configuration and would likely manifest with other corroborative areas of involvement.

Eczema (choice “b”) is certainly common in children, but it is unlikely to be relegated to one linear area. The same can be said of pityriasis rosea (choice “c”).

DISCUSSION

Lichen striatus, also known as Blaschko linear acquired skin inflammation, is an unusual self-limited condition of unknown etiology seen mostly on the extremities of children ages 3 to 10. More common on legs than on arms, it can occasionally appear on the face.

Its linear configuration is instantly diagnostic: The lesion typically follows the Blaschko lines, which represent a segmental clone of cutaneous cells deposited at an embryonic stage of development.

As seen in this case, postinflammatory hypopigmentation is common. In a minority of cases, the condition can involve the entire length of the extremity—even the digits, where it can lead to dystrophy of the affected nail. It almost always resolves within a few weeks to months, with or without treatment (which is limited to symptom relief).

Several potential causes of lichen striatus have been posited. The most convincing theory is a possible connection with human herpesviruses 6 and 7, which are also triggers for pityriasis rosea. There have been cases in which both conditions are present, producing somewhat similar microscopic changes in the skin (and both resolving without treatment). Additional items in the differential include lichen planus, lichen nitidus, and warts.

TREATMENT

For most cases of lichen striatus, treatment is supportive: topical steroids for the itching, which is seldom severe. Given the self-limited but prolonged nature of the problem, patient education is the more important component; these days, there are web-based sources to which you can direct your patients for reliable information, including the Mayo Clinic and the American Academy of Dermatology.

A 6-year-old boy is brought in by his mother, referred to dermatology for evaluation of a lesion on his right thigh that manifested three months ago. Although asymptomatic, the lesion has frightened the boy’s parents. They first took him to a local urgent care clinic, where a diagnosis of “probable fungal infection” was made. But twice-daily application of the prescribed ketoconazole cream did not produce results. The boy is otherwise healthy, although he does have seasonal allergies. There is no family history of skin problems. The affected site is a hypopigmented linear patch of skin from the mid-medial right thigh to the mid-medial calf area. The width of the patch varies, from 3 to 5 cm. The margins are somewhat irregular, and in several places, slightly rough, scaly sections are noted. The hypopigmentation, though partial, is evident in the context of the boy’s type IV Hispanic skin. No erythema or edema is noted. Elsewhere, the child’s skin is free of significant changes or lesions.