User login

The first part of this 2-part series addressed the basics of patch testing, including patch test systems, allergens, and patch test readings. In the second part of this series, we examine the incredibly important and absolutely vital steps that come after the patch test: determining relevance, patient counseling, and identifying allergen-free products for patient use. Let’s dive in!

Determining Relevance

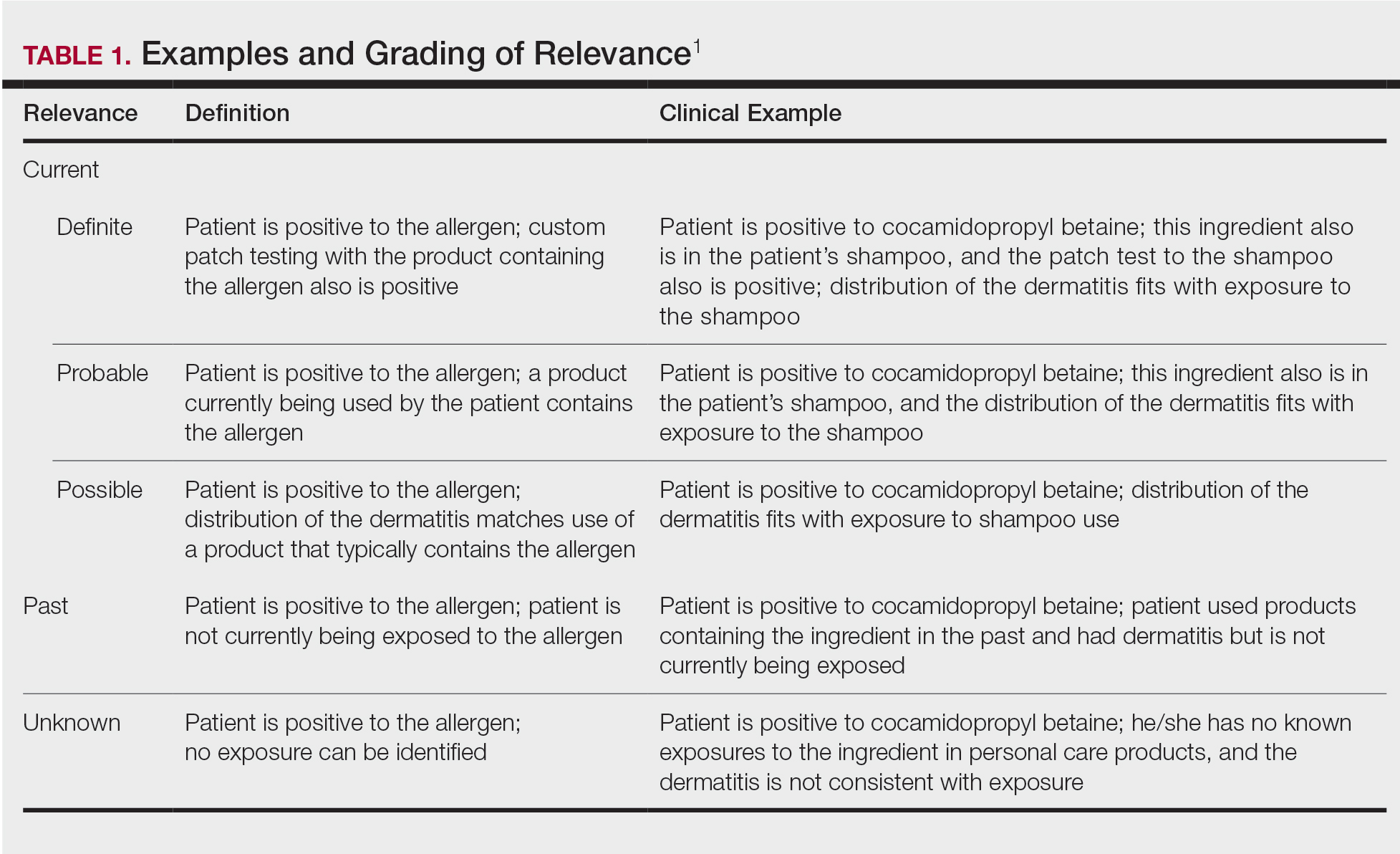

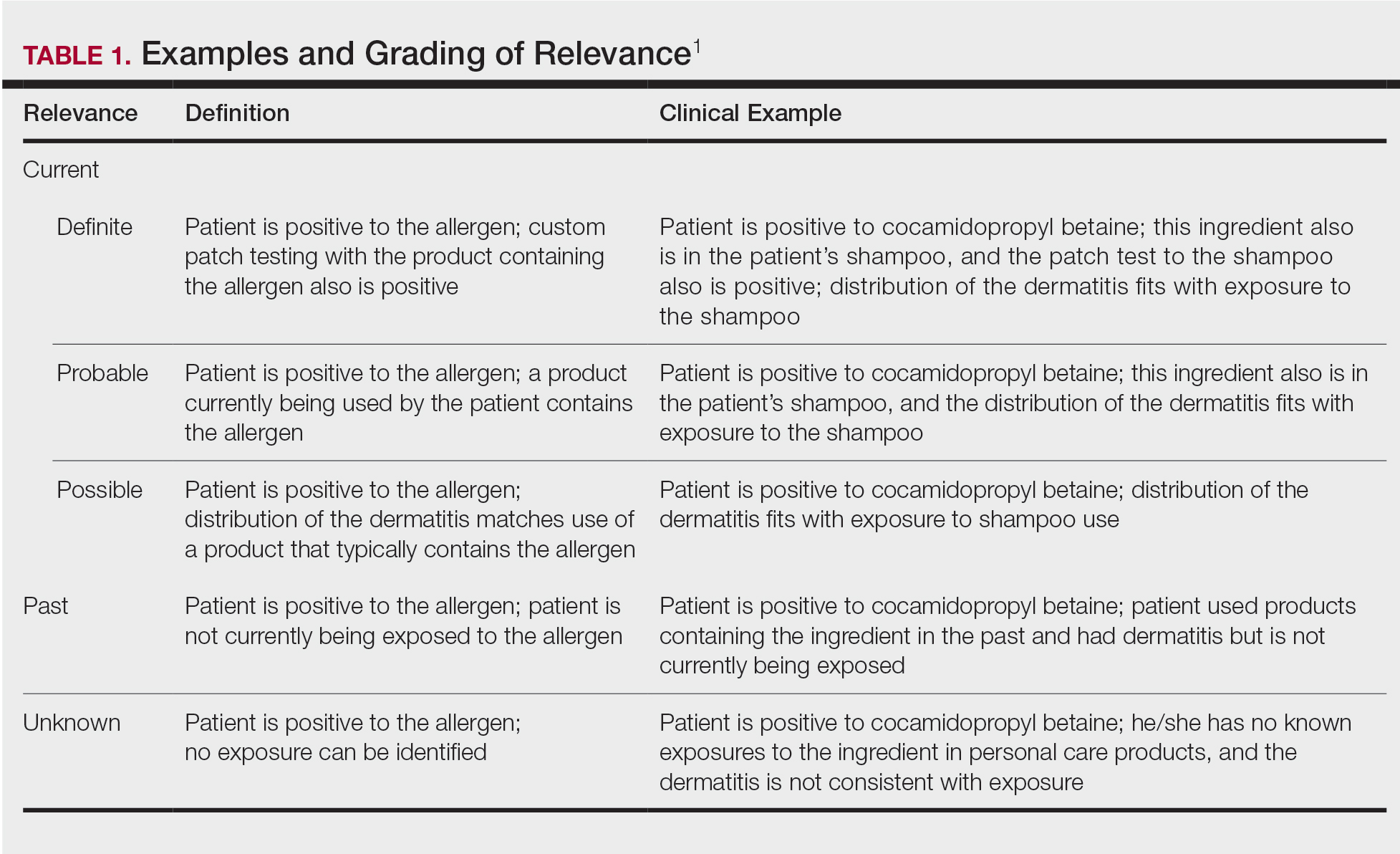

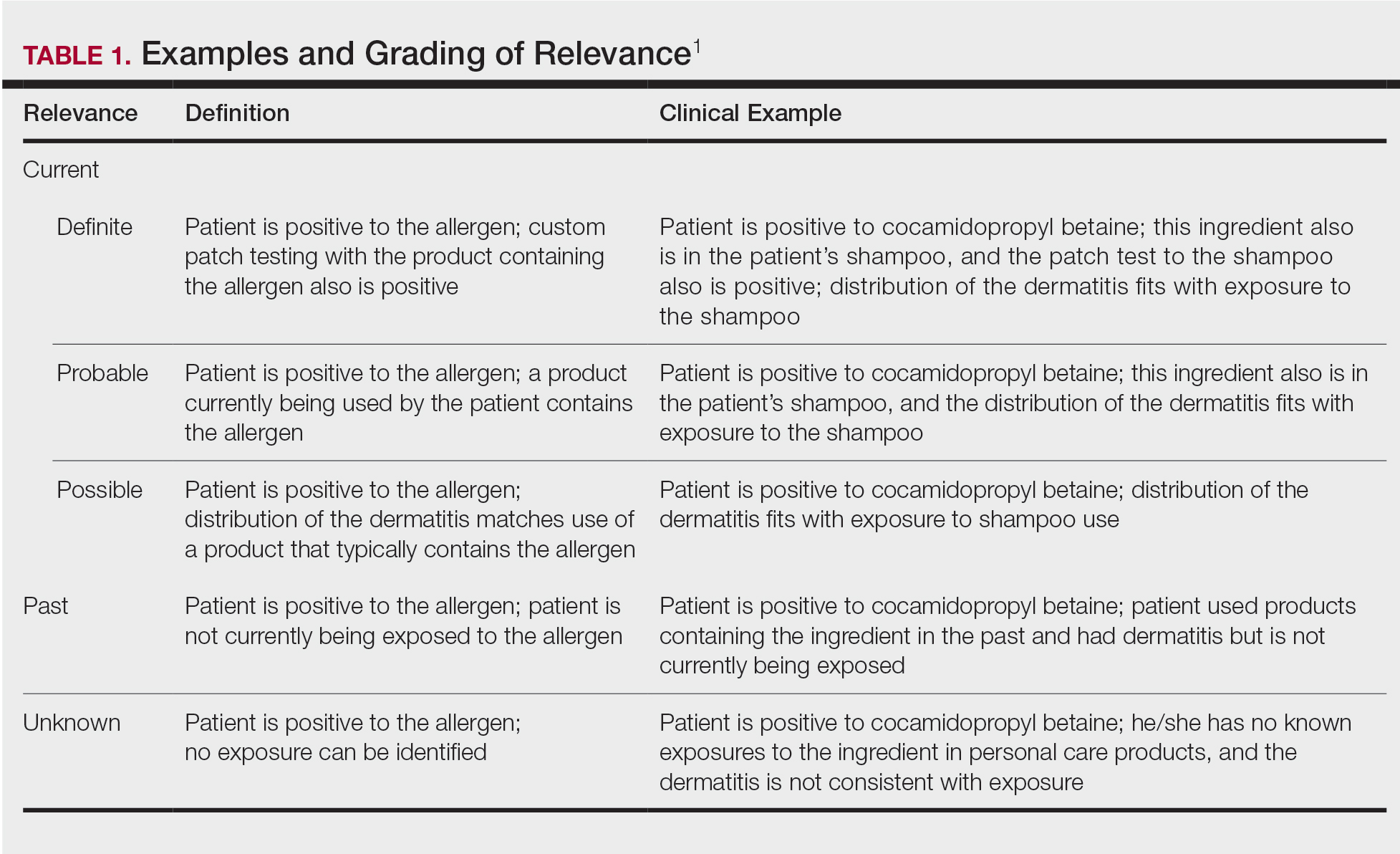

The purpose of determining relevance is to assess whether the positive patch test explains the patient’s dermatitis. It is important to consider all of the patient’s exposures, including at home, at work, and during recreational activities. Several relevance grading scales exist. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group grades relevance as current, past, or unknown. Current relevance is further divided into definite, probable, and possible.1 Table 1 includes explanations and clinical examples of each relevance type.

True relevance is only known weeks or months after patch testing is complete. If the patient avoids allergens and is subsequently free of dermatitis, the allergens identified through patch testing were relevant. However, if the patient avoids allergens and sees no improvement in dermatitis, the allergens were not relevant. Gipson et al2 analyzed relevance as documented by the physician at final patch test reading vs patient opinion of relevance 30 days to 3 years after the final reading and found that there was variable agreement between the 2 groups; percentage agreement for formaldehyde-releasing preservatives was 88%, neomycin was 78%, nickel was 71%, fragrances was 65%, and gold was 56%. These differences underscore the need for ongoing research on patch test methods, determination of relevance, and standards for patient follow-up.2

Patient Counseling

Patient counseling is one of the most important and complex parts of patch testing. We have consulted with patients who had already completed patch testing with other providers but did not receive comprehensive allergen counseling and therefore did not improve. It is up to you to explain positive allergens to your patients in a way that they understand, can retain long-term, and can use to their advantage to keep their skin free of dermatitis, which is an incredibly difficult feat to accomplish. The resources that we describe next are the very basic requirements for proficient patch testing.

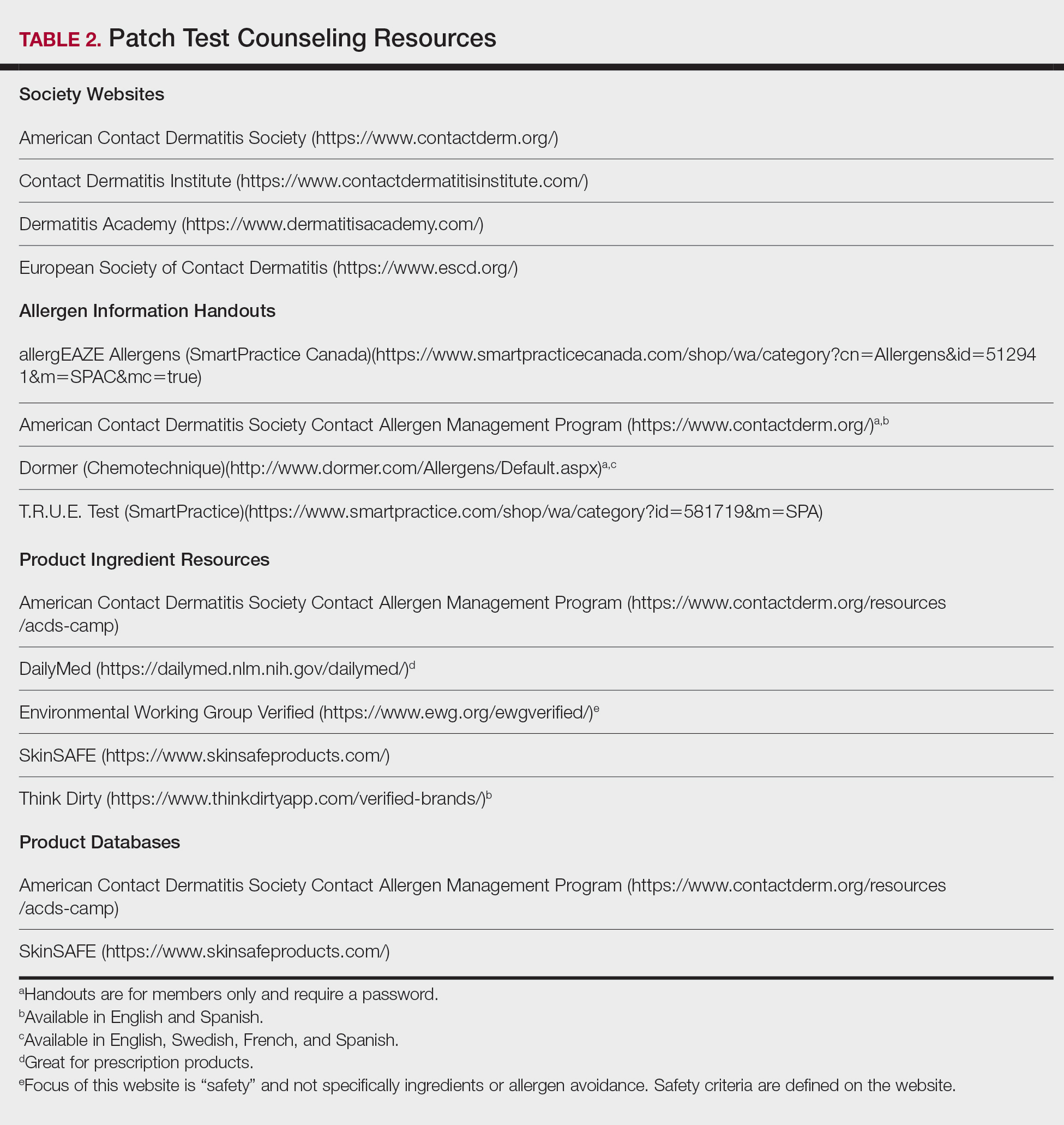

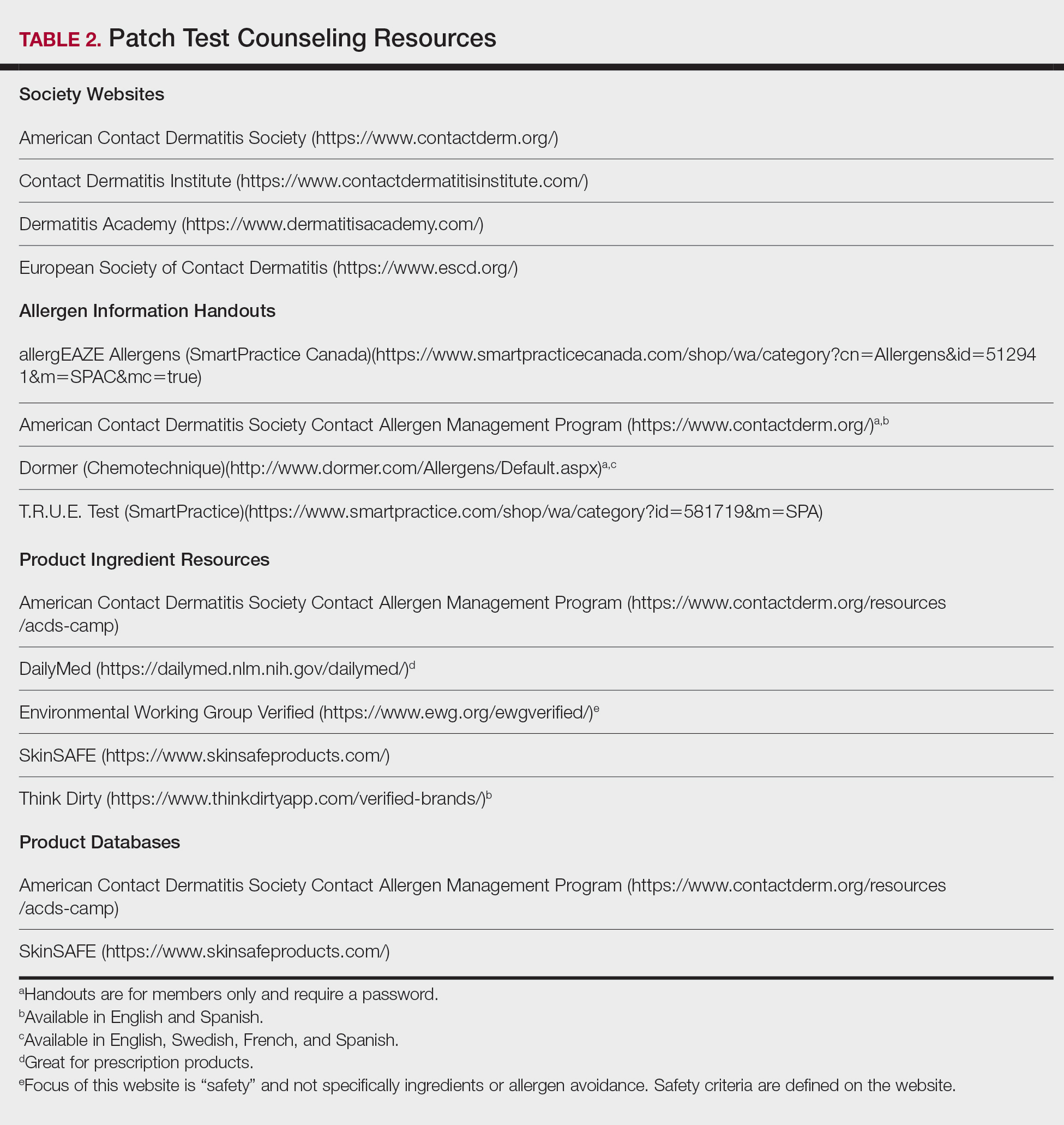

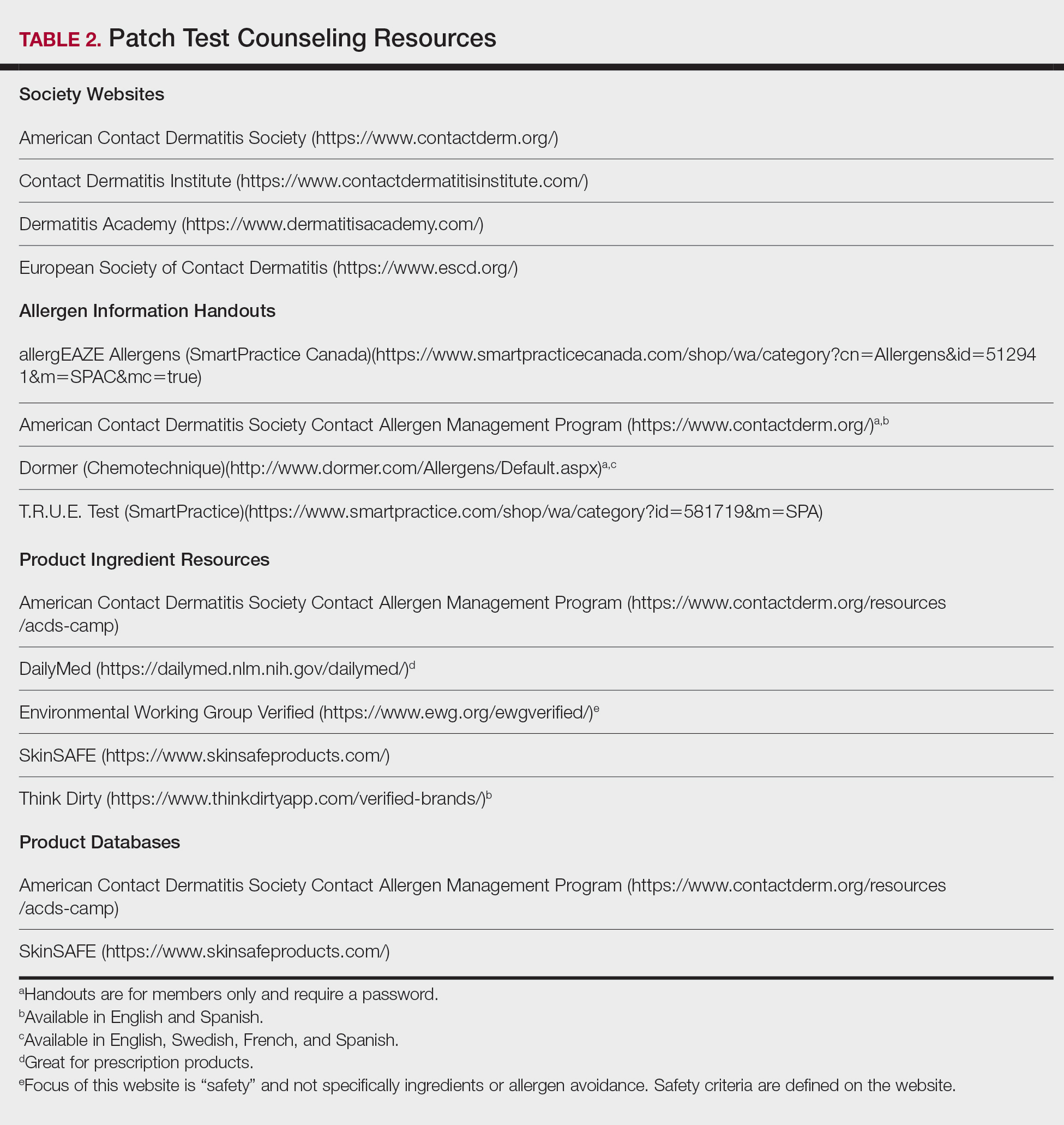

There are several tools that can be utilized to develop patch test counseling skills (Table 2). Membership with the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) includes opportunities for virtual and in-person (post–coronavirus disease 2019) lectures and conferences, videos, patch test support information, and patient resources. The European Society of Contact Dermatitis is similar, with a focus on European-based patch testers. Both societies are affiliated with academic journals—Dermatitis and Contact Dermatitis, respectively—which are phenomenal educational resources. Dermatitis Academy (https://www.dermatitisacademy.com) and Contact Dermatitis Institute (https://www.contactdermatitisinstitute.com) are websites that are privately designed and managed by US-based patch test experts.

Allergen Information Handouts

Allergen information should be presented in both verbal and written formats as well as in the patient’s preferred language and education level. Patch test counseling is detailed and complex. Patients rarely remember everything that is discussed; written information allows them to review again when necessary. Allergen information sheets typically include the name of the allergen, alternative names, types of products that might contain the allergen, and other pertinent facts. They also can be helpful for the physician who does not patch test full time; in this case, they can be used as a quick reference to guide patient counseling. It is helpful to highlight or underline important points and make notes when relevant. Importantly, reviewing information sheets with the patient allows time for questions.

Allergen information sheets are provided by manufacturers of patch test materials, including SmartPractice (allergEAZE, T.R.U.E. Test) and Chemotechnique (Dormer)(Table 2). The ACDS also provides a selection of allergen information sheets for members to share with their patients. The ACDS allergen handouts are designed for patient use, are vetted by practicing patch test dermatologists, and contain up-to-date information for patients. We recommend that you choose the handout(s) that are most appropriate for your patient; this decision can be made based on patient education or reading level, the region of the world where you are patch testing or where the patient lives, the patient’s primary language, and the specific allergen. Information on rare or new allergens may not be available on every website resource.

Identification of Allergen-Free Products

We ask patients to bring their personal care products to their patch test reading visit, and once positive allergens are known, we search for the presence of that allergen in their products. It is helpful for patients if products that are “safe” and “not safe” are sorted for them. We frequently emphasize that just one exposure to an allergen in a personal care product can be the source of the dermatitis. If a product label does not include ingredients, they often can be identified with a quick web search (use your favorite search engine or see Table 2 for websites); however, caution is advised, as lists found online may not match those found on in-store products.3 Reviewing the patient’s own products in the clinic is preferred over searching for ingredient lists online. If the product’s ingredients cannot be found (eg, ingredients that are found on external packaging), the patient has several choices: do not use, complete repeat open application testing if it is a leave-on product, or check to see if it is on a product database safe list.

We explain to patients that once they have confirmed that they are using only “safe” allergen-free products, it can take up to 6 to 8 weeks for dermatitis to improve, and at that point, the skin may only be about 75% to 80% clear. A clear description of what to expect and when is needed for a strong patient-physician partnership. For example, if the patient expects to be clear in 2 days but is not and stops avoiding their allergens because they think the process has failed, their dermatitis will not improve.

Product Databases

Because allergens sometimes have multiple different chemical names and cross-reactivity is abundant, avoidance of both the allergen and cross-reactors can be daunting for many patients (and dermatologists!). The use of a product database to aid in product selection is an invaluable resource. Product databases help patients avoid not only their allergens but also common cross-reactors by relying on complex cross-reactor programming. The ACDS owns and maintains the Contact Allergy Management Program (CAMP). Another resource is SkinSafe, which is powered by HER Inc and developed with the Mayo Clinic. Both CAMP and SkinSafe have mobile apps and update product lists frequently; they allow for much easier shopping and identification of safe products.

We typically use CAMP for generation of patient safe lists. We enter the patient’s allergens into the database, and a safe list is generated and shared with the patient. Next, we educate the patient on how to use the safe list. It is vital that the concept of exact product matching be explained to patients, as not all products from one brand or type of product is necessarily safe for a given individual. We also share information on how to download the CAMP app onto mobile devices and tablets.

Product safe lists are important resources for patients to be successful in avoiding allergens but are not a substitute for reading labels. Both CAMP and SkinSafe can potentially contain ingredient list errors due to companies frequently changing their product formulations.3 Although safe lists are an important part in selecting safe skin care products, they are not a substitute for label reading.

Counseling Pitfalls and Pearls

Language

Chemotechnique handouts are available in English, Swedish, French, and Spanish, and ACDS handouts are available in English and Spanish. If language interpretation is needed, inform the interpreter before the visit begins that you will be discussing patch test information and products so they can carefully interpret the details of the discussion.

Barriers to Allergen Avoidance

There are several barriers to long-term avoidance of contact allergy. In a European-based study of methylisothiazolinone (MI) contact allergy 2 to 5 years after patch testing, challenges described by patients included label reading, verifying products, difficulty obtaining ingredients of industrial products, the need to have their “safe” products always available for use, remembering allergen name, avoiding workplace allergens, finding acceptable MI-free products, and navigating the cost of MI-free products.4

Patient allergen recall is a well-documented long-term concern. In the previously mentioned European study (N=139), 11% of patients identified remembering the allergen name as a contributor to difficulty with avoidance.4 A Swedish study evaluated patient allergen recall at 1, 5, and 10 years after patch testing was completed; 96% of 252 patients remembered that they had completed patch testing, 79% (111/141) remembered that they had positive results, and only 29% (41/141) correctly recalled their allergens.5 Patients who had completed patch testing 10 years prior were less likely to correctly recall their allergens (P=.0045). Recall also was less likely if there was more than 1 allergen as well as in males.5 Korkmaz and Boyvat6 analyzed outcomes 6 months after patch testing in Turkey and found that 38 of 51 (74.5%) correctly recalled their allergens. Patients with more than 1 positive allergen were less likely to recall their allergens (P=.046), and patients with higher baseline investigator global assessment (P=.036) and dermatology life quality index (P=.041) scores were more likely to recall their allergens.6 A US-based study (N=757) noted that 34.1% of patients correctly recalled all of their allergens.7 Patients were less likely to remember if they had 3 or more positives but were more likely to remember if they were aged 50 to 59 years (compared to other age groups) or female as well as if their occupation was nursing (as compared to other occupations).

Additional barriers include hidden sources of allergens, as has been reported in the cases of undeclared MI8 and formaldehyde9 in personal care products. Although this phenomenon is thought to be the exception and not the rule, possible reasons for the presence of these undeclared allergens include their use as preservatives in raw materials,8,9 or in the case of formaldehyde, theorized release from product packaging or auto-oxidation and degradation of other chemicals present within the product.9

Readers may recall that we mentioned the option of identifying product ingredients with online search engines or databases, but it is not a perfect system. Comstock and Reeder3 reviewed and compared online ingredient lists from Amazon and several product databases to products taken off shelves at Target and Walgreens and found that 27.7% of online ingredient lists did not match the in-store labels.3 These differences likely are due to changes in product formulations, ingredient variability based on production site, outdated product on store shelves, or data entry error and may not be entirely avoidable. Regardless, patch test experts should be aware of this possibility. When in doubt, always check the product’s original packaging.

Finally, the elephant in the room: We challenge you, as dermatologists and patch test enthusiasts, to name all of the formaldehyde releasers or perhaps declare whether linalool and hydroxycitronellol are fragrances, preservatives, or surfactants. How about naming the relationship between cocamidopropyl betaine, amidoamine, and dimethylaminopropylamine? Difficult stuff, right? And we are medical specialists. It is downright impossible for many of our patients to memorize the names of these chemicals, let alone know their cross-reactors or other important chemical relationships. We mention that providing a safe list is part of patient counseling, but we bring up this knowledge gap to illustrate that patch testing without providing resources to select safe care products is almost as bad as not patch testing at all because in many cases patients may be left without the tools they need to be successful. Do not let this be your downfall!

Final Interpretation

The most challenging and nuanced part of patch testing happens after the actual patch test: assessment of relevance, allergen counseling, and identification of appropriate products for patient use. You now have the tools to successfully counsel your patients after patch testing; get to it!

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Zug KA, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2015-2016. Dermatitis. 2018;29:297-309.

- Gipson KA, Carlson SW, Nedorost ST. Physician-patient agreement in the assessment of allergen relevance. Dermatitis. 2010;21:275-279.

- Comstock JR, Reeder MJ. Accuracy of product ingredient labeling: comparing drugstore products with online databases and online retailers. Dermatitis. 2020;31:106-111.

- Bouschon P, Waton J, Pereira B, et al. Methylisothiazolinone allergic contact dermatitis: assessment of relapses in 139 patients after avoidance advice. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:304-310.

- Jamil WN, Erikssohn I, Lindberg M. How well is the outcome of patch testing remembered by the patients? a 10-year follow-up of testing with the Swedish baseline series at the department of dermatology in Örebro, Sweden. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:215-220.

- Korkmaz P, Boyvat A. Effect of patch testing on the course of allergic contact dermatitis and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. Dermatitis. 2019;30:135-141.

- Scalf LA, Genebriera J, Davis MD, et al. Patients’ perceptions of the usefulness and outcome of patch testing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:928-932.

- Kerre S, Naessens T, Theunis M, et al. Facial dermatitis caused by undeclared methylisothiazolinone in a gel mask: is the preservation of raw materials in cosmetics a cause of concern? Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:421-424.

- Nikle A, Ericson M, Warshaw E. Formaldehyde release from personal care products: chromotropic acid method analysis. Dermatitis. 2019;30:67-73.

The first part of this 2-part series addressed the basics of patch testing, including patch test systems, allergens, and patch test readings. In the second part of this series, we examine the incredibly important and absolutely vital steps that come after the patch test: determining relevance, patient counseling, and identifying allergen-free products for patient use. Let’s dive in!

Determining Relevance

The purpose of determining relevance is to assess whether the positive patch test explains the patient’s dermatitis. It is important to consider all of the patient’s exposures, including at home, at work, and during recreational activities. Several relevance grading scales exist. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group grades relevance as current, past, or unknown. Current relevance is further divided into definite, probable, and possible.1 Table 1 includes explanations and clinical examples of each relevance type.

True relevance is only known weeks or months after patch testing is complete. If the patient avoids allergens and is subsequently free of dermatitis, the allergens identified through patch testing were relevant. However, if the patient avoids allergens and sees no improvement in dermatitis, the allergens were not relevant. Gipson et al2 analyzed relevance as documented by the physician at final patch test reading vs patient opinion of relevance 30 days to 3 years after the final reading and found that there was variable agreement between the 2 groups; percentage agreement for formaldehyde-releasing preservatives was 88%, neomycin was 78%, nickel was 71%, fragrances was 65%, and gold was 56%. These differences underscore the need for ongoing research on patch test methods, determination of relevance, and standards for patient follow-up.2

Patient Counseling

Patient counseling is one of the most important and complex parts of patch testing. We have consulted with patients who had already completed patch testing with other providers but did not receive comprehensive allergen counseling and therefore did not improve. It is up to you to explain positive allergens to your patients in a way that they understand, can retain long-term, and can use to their advantage to keep their skin free of dermatitis, which is an incredibly difficult feat to accomplish. The resources that we describe next are the very basic requirements for proficient patch testing.

There are several tools that can be utilized to develop patch test counseling skills (Table 2). Membership with the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) includes opportunities for virtual and in-person (post–coronavirus disease 2019) lectures and conferences, videos, patch test support information, and patient resources. The European Society of Contact Dermatitis is similar, with a focus on European-based patch testers. Both societies are affiliated with academic journals—Dermatitis and Contact Dermatitis, respectively—which are phenomenal educational resources. Dermatitis Academy (https://www.dermatitisacademy.com) and Contact Dermatitis Institute (https://www.contactdermatitisinstitute.com) are websites that are privately designed and managed by US-based patch test experts.

Allergen Information Handouts

Allergen information should be presented in both verbal and written formats as well as in the patient’s preferred language and education level. Patch test counseling is detailed and complex. Patients rarely remember everything that is discussed; written information allows them to review again when necessary. Allergen information sheets typically include the name of the allergen, alternative names, types of products that might contain the allergen, and other pertinent facts. They also can be helpful for the physician who does not patch test full time; in this case, they can be used as a quick reference to guide patient counseling. It is helpful to highlight or underline important points and make notes when relevant. Importantly, reviewing information sheets with the patient allows time for questions.

Allergen information sheets are provided by manufacturers of patch test materials, including SmartPractice (allergEAZE, T.R.U.E. Test) and Chemotechnique (Dormer)(Table 2). The ACDS also provides a selection of allergen information sheets for members to share with their patients. The ACDS allergen handouts are designed for patient use, are vetted by practicing patch test dermatologists, and contain up-to-date information for patients. We recommend that you choose the handout(s) that are most appropriate for your patient; this decision can be made based on patient education or reading level, the region of the world where you are patch testing or where the patient lives, the patient’s primary language, and the specific allergen. Information on rare or new allergens may not be available on every website resource.

Identification of Allergen-Free Products

We ask patients to bring their personal care products to their patch test reading visit, and once positive allergens are known, we search for the presence of that allergen in their products. It is helpful for patients if products that are “safe” and “not safe” are sorted for them. We frequently emphasize that just one exposure to an allergen in a personal care product can be the source of the dermatitis. If a product label does not include ingredients, they often can be identified with a quick web search (use your favorite search engine or see Table 2 for websites); however, caution is advised, as lists found online may not match those found on in-store products.3 Reviewing the patient’s own products in the clinic is preferred over searching for ingredient lists online. If the product’s ingredients cannot be found (eg, ingredients that are found on external packaging), the patient has several choices: do not use, complete repeat open application testing if it is a leave-on product, or check to see if it is on a product database safe list.

We explain to patients that once they have confirmed that they are using only “safe” allergen-free products, it can take up to 6 to 8 weeks for dermatitis to improve, and at that point, the skin may only be about 75% to 80% clear. A clear description of what to expect and when is needed for a strong patient-physician partnership. For example, if the patient expects to be clear in 2 days but is not and stops avoiding their allergens because they think the process has failed, their dermatitis will not improve.

Product Databases

Because allergens sometimes have multiple different chemical names and cross-reactivity is abundant, avoidance of both the allergen and cross-reactors can be daunting for many patients (and dermatologists!). The use of a product database to aid in product selection is an invaluable resource. Product databases help patients avoid not only their allergens but also common cross-reactors by relying on complex cross-reactor programming. The ACDS owns and maintains the Contact Allergy Management Program (CAMP). Another resource is SkinSafe, which is powered by HER Inc and developed with the Mayo Clinic. Both CAMP and SkinSafe have mobile apps and update product lists frequently; they allow for much easier shopping and identification of safe products.

We typically use CAMP for generation of patient safe lists. We enter the patient’s allergens into the database, and a safe list is generated and shared with the patient. Next, we educate the patient on how to use the safe list. It is vital that the concept of exact product matching be explained to patients, as not all products from one brand or type of product is necessarily safe for a given individual. We also share information on how to download the CAMP app onto mobile devices and tablets.

Product safe lists are important resources for patients to be successful in avoiding allergens but are not a substitute for reading labels. Both CAMP and SkinSafe can potentially contain ingredient list errors due to companies frequently changing their product formulations.3 Although safe lists are an important part in selecting safe skin care products, they are not a substitute for label reading.

Counseling Pitfalls and Pearls

Language

Chemotechnique handouts are available in English, Swedish, French, and Spanish, and ACDS handouts are available in English and Spanish. If language interpretation is needed, inform the interpreter before the visit begins that you will be discussing patch test information and products so they can carefully interpret the details of the discussion.

Barriers to Allergen Avoidance

There are several barriers to long-term avoidance of contact allergy. In a European-based study of methylisothiazolinone (MI) contact allergy 2 to 5 years after patch testing, challenges described by patients included label reading, verifying products, difficulty obtaining ingredients of industrial products, the need to have their “safe” products always available for use, remembering allergen name, avoiding workplace allergens, finding acceptable MI-free products, and navigating the cost of MI-free products.4

Patient allergen recall is a well-documented long-term concern. In the previously mentioned European study (N=139), 11% of patients identified remembering the allergen name as a contributor to difficulty with avoidance.4 A Swedish study evaluated patient allergen recall at 1, 5, and 10 years after patch testing was completed; 96% of 252 patients remembered that they had completed patch testing, 79% (111/141) remembered that they had positive results, and only 29% (41/141) correctly recalled their allergens.5 Patients who had completed patch testing 10 years prior were less likely to correctly recall their allergens (P=.0045). Recall also was less likely if there was more than 1 allergen as well as in males.5 Korkmaz and Boyvat6 analyzed outcomes 6 months after patch testing in Turkey and found that 38 of 51 (74.5%) correctly recalled their allergens. Patients with more than 1 positive allergen were less likely to recall their allergens (P=.046), and patients with higher baseline investigator global assessment (P=.036) and dermatology life quality index (P=.041) scores were more likely to recall their allergens.6 A US-based study (N=757) noted that 34.1% of patients correctly recalled all of their allergens.7 Patients were less likely to remember if they had 3 or more positives but were more likely to remember if they were aged 50 to 59 years (compared to other age groups) or female as well as if their occupation was nursing (as compared to other occupations).

Additional barriers include hidden sources of allergens, as has been reported in the cases of undeclared MI8 and formaldehyde9 in personal care products. Although this phenomenon is thought to be the exception and not the rule, possible reasons for the presence of these undeclared allergens include their use as preservatives in raw materials,8,9 or in the case of formaldehyde, theorized release from product packaging or auto-oxidation and degradation of other chemicals present within the product.9

Readers may recall that we mentioned the option of identifying product ingredients with online search engines or databases, but it is not a perfect system. Comstock and Reeder3 reviewed and compared online ingredient lists from Amazon and several product databases to products taken off shelves at Target and Walgreens and found that 27.7% of online ingredient lists did not match the in-store labels.3 These differences likely are due to changes in product formulations, ingredient variability based on production site, outdated product on store shelves, or data entry error and may not be entirely avoidable. Regardless, patch test experts should be aware of this possibility. When in doubt, always check the product’s original packaging.

Finally, the elephant in the room: We challenge you, as dermatologists and patch test enthusiasts, to name all of the formaldehyde releasers or perhaps declare whether linalool and hydroxycitronellol are fragrances, preservatives, or surfactants. How about naming the relationship between cocamidopropyl betaine, amidoamine, and dimethylaminopropylamine? Difficult stuff, right? And we are medical specialists. It is downright impossible for many of our patients to memorize the names of these chemicals, let alone know their cross-reactors or other important chemical relationships. We mention that providing a safe list is part of patient counseling, but we bring up this knowledge gap to illustrate that patch testing without providing resources to select safe care products is almost as bad as not patch testing at all because in many cases patients may be left without the tools they need to be successful. Do not let this be your downfall!

Final Interpretation

The most challenging and nuanced part of patch testing happens after the actual patch test: assessment of relevance, allergen counseling, and identification of appropriate products for patient use. You now have the tools to successfully counsel your patients after patch testing; get to it!

The first part of this 2-part series addressed the basics of patch testing, including patch test systems, allergens, and patch test readings. In the second part of this series, we examine the incredibly important and absolutely vital steps that come after the patch test: determining relevance, patient counseling, and identifying allergen-free products for patient use. Let’s dive in!

Determining Relevance

The purpose of determining relevance is to assess whether the positive patch test explains the patient’s dermatitis. It is important to consider all of the patient’s exposures, including at home, at work, and during recreational activities. Several relevance grading scales exist. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group grades relevance as current, past, or unknown. Current relevance is further divided into definite, probable, and possible.1 Table 1 includes explanations and clinical examples of each relevance type.

True relevance is only known weeks or months after patch testing is complete. If the patient avoids allergens and is subsequently free of dermatitis, the allergens identified through patch testing were relevant. However, if the patient avoids allergens and sees no improvement in dermatitis, the allergens were not relevant. Gipson et al2 analyzed relevance as documented by the physician at final patch test reading vs patient opinion of relevance 30 days to 3 years after the final reading and found that there was variable agreement between the 2 groups; percentage agreement for formaldehyde-releasing preservatives was 88%, neomycin was 78%, nickel was 71%, fragrances was 65%, and gold was 56%. These differences underscore the need for ongoing research on patch test methods, determination of relevance, and standards for patient follow-up.2

Patient Counseling

Patient counseling is one of the most important and complex parts of patch testing. We have consulted with patients who had already completed patch testing with other providers but did not receive comprehensive allergen counseling and therefore did not improve. It is up to you to explain positive allergens to your patients in a way that they understand, can retain long-term, and can use to their advantage to keep their skin free of dermatitis, which is an incredibly difficult feat to accomplish. The resources that we describe next are the very basic requirements for proficient patch testing.

There are several tools that can be utilized to develop patch test counseling skills (Table 2). Membership with the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) includes opportunities for virtual and in-person (post–coronavirus disease 2019) lectures and conferences, videos, patch test support information, and patient resources. The European Society of Contact Dermatitis is similar, with a focus on European-based patch testers. Both societies are affiliated with academic journals—Dermatitis and Contact Dermatitis, respectively—which are phenomenal educational resources. Dermatitis Academy (https://www.dermatitisacademy.com) and Contact Dermatitis Institute (https://www.contactdermatitisinstitute.com) are websites that are privately designed and managed by US-based patch test experts.

Allergen Information Handouts

Allergen information should be presented in both verbal and written formats as well as in the patient’s preferred language and education level. Patch test counseling is detailed and complex. Patients rarely remember everything that is discussed; written information allows them to review again when necessary. Allergen information sheets typically include the name of the allergen, alternative names, types of products that might contain the allergen, and other pertinent facts. They also can be helpful for the physician who does not patch test full time; in this case, they can be used as a quick reference to guide patient counseling. It is helpful to highlight or underline important points and make notes when relevant. Importantly, reviewing information sheets with the patient allows time for questions.

Allergen information sheets are provided by manufacturers of patch test materials, including SmartPractice (allergEAZE, T.R.U.E. Test) and Chemotechnique (Dormer)(Table 2). The ACDS also provides a selection of allergen information sheets for members to share with their patients. The ACDS allergen handouts are designed for patient use, are vetted by practicing patch test dermatologists, and contain up-to-date information for patients. We recommend that you choose the handout(s) that are most appropriate for your patient; this decision can be made based on patient education or reading level, the region of the world where you are patch testing or where the patient lives, the patient’s primary language, and the specific allergen. Information on rare or new allergens may not be available on every website resource.

Identification of Allergen-Free Products

We ask patients to bring their personal care products to their patch test reading visit, and once positive allergens are known, we search for the presence of that allergen in their products. It is helpful for patients if products that are “safe” and “not safe” are sorted for them. We frequently emphasize that just one exposure to an allergen in a personal care product can be the source of the dermatitis. If a product label does not include ingredients, they often can be identified with a quick web search (use your favorite search engine or see Table 2 for websites); however, caution is advised, as lists found online may not match those found on in-store products.3 Reviewing the patient’s own products in the clinic is preferred over searching for ingredient lists online. If the product’s ingredients cannot be found (eg, ingredients that are found on external packaging), the patient has several choices: do not use, complete repeat open application testing if it is a leave-on product, or check to see if it is on a product database safe list.

We explain to patients that once they have confirmed that they are using only “safe” allergen-free products, it can take up to 6 to 8 weeks for dermatitis to improve, and at that point, the skin may only be about 75% to 80% clear. A clear description of what to expect and when is needed for a strong patient-physician partnership. For example, if the patient expects to be clear in 2 days but is not and stops avoiding their allergens because they think the process has failed, their dermatitis will not improve.

Product Databases

Because allergens sometimes have multiple different chemical names and cross-reactivity is abundant, avoidance of both the allergen and cross-reactors can be daunting for many patients (and dermatologists!). The use of a product database to aid in product selection is an invaluable resource. Product databases help patients avoid not only their allergens but also common cross-reactors by relying on complex cross-reactor programming. The ACDS owns and maintains the Contact Allergy Management Program (CAMP). Another resource is SkinSafe, which is powered by HER Inc and developed with the Mayo Clinic. Both CAMP and SkinSafe have mobile apps and update product lists frequently; they allow for much easier shopping and identification of safe products.

We typically use CAMP for generation of patient safe lists. We enter the patient’s allergens into the database, and a safe list is generated and shared with the patient. Next, we educate the patient on how to use the safe list. It is vital that the concept of exact product matching be explained to patients, as not all products from one brand or type of product is necessarily safe for a given individual. We also share information on how to download the CAMP app onto mobile devices and tablets.

Product safe lists are important resources for patients to be successful in avoiding allergens but are not a substitute for reading labels. Both CAMP and SkinSafe can potentially contain ingredient list errors due to companies frequently changing their product formulations.3 Although safe lists are an important part in selecting safe skin care products, they are not a substitute for label reading.

Counseling Pitfalls and Pearls

Language

Chemotechnique handouts are available in English, Swedish, French, and Spanish, and ACDS handouts are available in English and Spanish. If language interpretation is needed, inform the interpreter before the visit begins that you will be discussing patch test information and products so they can carefully interpret the details of the discussion.

Barriers to Allergen Avoidance

There are several barriers to long-term avoidance of contact allergy. In a European-based study of methylisothiazolinone (MI) contact allergy 2 to 5 years after patch testing, challenges described by patients included label reading, verifying products, difficulty obtaining ingredients of industrial products, the need to have their “safe” products always available for use, remembering allergen name, avoiding workplace allergens, finding acceptable MI-free products, and navigating the cost of MI-free products.4

Patient allergen recall is a well-documented long-term concern. In the previously mentioned European study (N=139), 11% of patients identified remembering the allergen name as a contributor to difficulty with avoidance.4 A Swedish study evaluated patient allergen recall at 1, 5, and 10 years after patch testing was completed; 96% of 252 patients remembered that they had completed patch testing, 79% (111/141) remembered that they had positive results, and only 29% (41/141) correctly recalled their allergens.5 Patients who had completed patch testing 10 years prior were less likely to correctly recall their allergens (P=.0045). Recall also was less likely if there was more than 1 allergen as well as in males.5 Korkmaz and Boyvat6 analyzed outcomes 6 months after patch testing in Turkey and found that 38 of 51 (74.5%) correctly recalled their allergens. Patients with more than 1 positive allergen were less likely to recall their allergens (P=.046), and patients with higher baseline investigator global assessment (P=.036) and dermatology life quality index (P=.041) scores were more likely to recall their allergens.6 A US-based study (N=757) noted that 34.1% of patients correctly recalled all of their allergens.7 Patients were less likely to remember if they had 3 or more positives but were more likely to remember if they were aged 50 to 59 years (compared to other age groups) or female as well as if their occupation was nursing (as compared to other occupations).

Additional barriers include hidden sources of allergens, as has been reported in the cases of undeclared MI8 and formaldehyde9 in personal care products. Although this phenomenon is thought to be the exception and not the rule, possible reasons for the presence of these undeclared allergens include their use as preservatives in raw materials,8,9 or in the case of formaldehyde, theorized release from product packaging or auto-oxidation and degradation of other chemicals present within the product.9

Readers may recall that we mentioned the option of identifying product ingredients with online search engines or databases, but it is not a perfect system. Comstock and Reeder3 reviewed and compared online ingredient lists from Amazon and several product databases to products taken off shelves at Target and Walgreens and found that 27.7% of online ingredient lists did not match the in-store labels.3 These differences likely are due to changes in product formulations, ingredient variability based on production site, outdated product on store shelves, or data entry error and may not be entirely avoidable. Regardless, patch test experts should be aware of this possibility. When in doubt, always check the product’s original packaging.

Finally, the elephant in the room: We challenge you, as dermatologists and patch test enthusiasts, to name all of the formaldehyde releasers or perhaps declare whether linalool and hydroxycitronellol are fragrances, preservatives, or surfactants. How about naming the relationship between cocamidopropyl betaine, amidoamine, and dimethylaminopropylamine? Difficult stuff, right? And we are medical specialists. It is downright impossible for many of our patients to memorize the names of these chemicals, let alone know their cross-reactors or other important chemical relationships. We mention that providing a safe list is part of patient counseling, but we bring up this knowledge gap to illustrate that patch testing without providing resources to select safe care products is almost as bad as not patch testing at all because in many cases patients may be left without the tools they need to be successful. Do not let this be your downfall!

Final Interpretation

The most challenging and nuanced part of patch testing happens after the actual patch test: assessment of relevance, allergen counseling, and identification of appropriate products for patient use. You now have the tools to successfully counsel your patients after patch testing; get to it!

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Zug KA, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2015-2016. Dermatitis. 2018;29:297-309.

- Gipson KA, Carlson SW, Nedorost ST. Physician-patient agreement in the assessment of allergen relevance. Dermatitis. 2010;21:275-279.

- Comstock JR, Reeder MJ. Accuracy of product ingredient labeling: comparing drugstore products with online databases and online retailers. Dermatitis. 2020;31:106-111.

- Bouschon P, Waton J, Pereira B, et al. Methylisothiazolinone allergic contact dermatitis: assessment of relapses in 139 patients after avoidance advice. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:304-310.

- Jamil WN, Erikssohn I, Lindberg M. How well is the outcome of patch testing remembered by the patients? a 10-year follow-up of testing with the Swedish baseline series at the department of dermatology in Örebro, Sweden. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:215-220.

- Korkmaz P, Boyvat A. Effect of patch testing on the course of allergic contact dermatitis and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. Dermatitis. 2019;30:135-141.

- Scalf LA, Genebriera J, Davis MD, et al. Patients’ perceptions of the usefulness and outcome of patch testing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:928-932.

- Kerre S, Naessens T, Theunis M, et al. Facial dermatitis caused by undeclared methylisothiazolinone in a gel mask: is the preservation of raw materials in cosmetics a cause of concern? Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:421-424.

- Nikle A, Ericson M, Warshaw E. Formaldehyde release from personal care products: chromotropic acid method analysis. Dermatitis. 2019;30:67-73.

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Zug KA, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group patch test results: 2015-2016. Dermatitis. 2018;29:297-309.

- Gipson KA, Carlson SW, Nedorost ST. Physician-patient agreement in the assessment of allergen relevance. Dermatitis. 2010;21:275-279.

- Comstock JR, Reeder MJ. Accuracy of product ingredient labeling: comparing drugstore products with online databases and online retailers. Dermatitis. 2020;31:106-111.

- Bouschon P, Waton J, Pereira B, et al. Methylisothiazolinone allergic contact dermatitis: assessment of relapses in 139 patients after avoidance advice. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;80:304-310.

- Jamil WN, Erikssohn I, Lindberg M. How well is the outcome of patch testing remembered by the patients? a 10-year follow-up of testing with the Swedish baseline series at the department of dermatology in Örebro, Sweden. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:215-220.

- Korkmaz P, Boyvat A. Effect of patch testing on the course of allergic contact dermatitis and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. Dermatitis. 2019;30:135-141.

- Scalf LA, Genebriera J, Davis MD, et al. Patients’ perceptions of the usefulness and outcome of patch testing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:928-932.

- Kerre S, Naessens T, Theunis M, et al. Facial dermatitis caused by undeclared methylisothiazolinone in a gel mask: is the preservation of raw materials in cosmetics a cause of concern? Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:421-424.

- Nikle A, Ericson M, Warshaw E. Formaldehyde release from personal care products: chromotropic acid method analysis. Dermatitis. 2019;30:67-73.

Practice Points

- Positive patch test reactions must be interpreted in the context of the patient’s exposures, both current and past.

- Allergen information sheets and product database safe lists are invaluable tools to help patients select safe skin care products.