User login

Emergency department personnel at a remote hospital called Dr. James P. Marcin regarding a baby who was just admitted with an upper respiratory infection. Because the patient had cyanotic congenital heart disease, the team was concerned she was too medically complex for their facility, and they were preparing to helicopter her to the pediatric intensive care unit at the University of California, Davis, Children’s Hospital in Sacramento.

But when Dr. Marcin examined the baby via a two-way video, he remembered the child from a previous visit. Although her oxygen levels were low, Dr. Marcin knew they were normal for her condition. Dr. Marcin spoke with the patient’s parents and after learning more about the patient’s symptoms, he was confident the child could remain at the small hospital. She was treated for the upper respiratory infection and later sent home where she improved, said Dr. Marcin, who leads the Pediatric Telemedicine Program at UC Davis.

Despite the positive outcome, Dr. Marcin’s claim was denied by the insurance company, he said.

“Had I not used telemedicine, that child would have been put in a helicopter, flown to our ICU, [and likely incurred] some $20,000 bill,” Dr. Marcin said in an interview. “I saved the insurance company $20,000, and then they ended up denying my 2 hours of critical care time. It’s discouraging.”

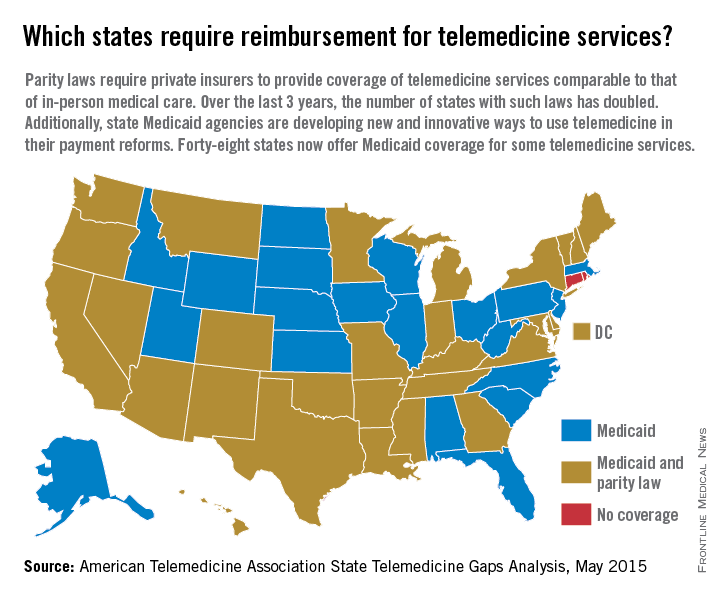

Reimbursement struggles are playing out in medical practices and hospitals across the country. While insurance coverage for telemedicine is growing, experts say payment remains one of the most pressing challenges. So far, 29 states and the District of Columbia have laws that require full parity of coverage and reimbursement for telemedicine services comparable to that of in-person services, according to the American Telemedicine Association (ATA). Medicaid programs in almost all (48) states require some form of compensation for telemedicine, according to a 2015 ATA report.

Payment parity for telemedicine has doubled in the last 2 years, noted Dr. Reed V. Tuckson, ATA president.

“We are seeing, on the side of the private insurance world, really exciting acceptance of telehealth services,” Dr. Tuckson said in an interview. There has been “really great movement forward.”

Enforcement of those parity laws can be spotty, said René Y. Quashie, a Washington health law attorney.

“It’s a mixed bag,” Mr. Quashie said in an interview. “In some states, enforcement is lax so you still have a lot of providers submitting claims that are not being paid or not being paid timely.”

State support equals payment success

In rural Wrightsville, Ga., Dr. Jean R. Sumner regularly gets paid to provide telemedicine. Georgia enacted its parity law in 2006 and has greatly embraced telemedicine capabilities, particularly for its rural populations, said Dr. Sumner, associate dean for rural health at Mercer University in Macon. Part of the success is because of the Georgia Partnership for TeleHealth, a statewide network that focuses on increasing access to care through telemedicine. Its hallmark is the state’s open access network, a web of access points based on existing telemedicine programs that enables secure health information exchange. The goal of the program is for all rural Georgians to access specialty care within 30 miles of their homes.

The state’s strong support of telemedicine contributes to payers taking the modality seriously and doctors getting paid for telemedicine care, Dr. Sumner said in an interview.

“Most insurers pay as long as the visit is equal or superior to an exam done in person,” she said. “It has to be quality care.”

Dr. Sumner also can bill a site fee when telemedicine technology is used at her practice, she said. If a patient visits her practice for a psychiatric consultation while Dr. Sumner is busy, for example, a nurse can connect the patient to a psychiatrist through the office’s telemedicine unit. The site fee is minimal, but it helps cover costs, she said.

In states that do not have parity laws, some larger health plans, such as Anthem and UnitedHealthcare, have proactively covered telemedicine services, said Dr. Peter Antall, president and medical director of American Well’s Online Care Group, a national telehealth service. Smaller health plans on the other hand, are sometimes willing to negotiate with providers and consider adding telemedicine services to a fee schedule, Dr. Antall said in an interview.

“I think we’re moving into a phase where reimbursement is normal or expected in telehealth,” he said. “We’re not quite there yet because there are so many health plans and, within the health plans, there are so many different products and subgroups. It’s still a process that needs to evolve.”

Government payers lag behind

Medicaid policies also vary from state by state. Some state programs cover telemedicine services similar to that of in-person treatment. Others limit coverage by technology or geographic area.

Medicare, by far, ranks the worst in paying physicians for telemedicine, experts said. Of $597 billion in total Medicare payments in 2014, 0.0023% was spent on telemedicine, according to data provided to the Robert J. Waters Center for Telehealth & e-Health Law.

“Unless you’re a patient that presents in a rural community, the Medicare telehealth benefit is not available,” said Mr. Quashie, who is part of the CTeL’s legal resource team. “Medicare is almost a no-go under fee-for-service for telehealth.”

CMS reimburses physicians for telemedicine only when the originating site is in a Health Professional Shortage Area or within a county outside a Metropolitan Statistical Area. The originating site must be a medical facility and not the patient’s home. CMS covers care only on an approved list of medical services.

In its 2016 proposed fee schedule, CMS recommended adding two new codes to its accepted telemedicine services, including codes for prolonged service inpatient care and end-stage renal disease–related services. However, the agency denied a handful of other services requested by the ATA and again, refused to end its patient site limitations.

“We are very concerned about Medicare’s decisions in terms of its ability and willingness to reimburse” telehealth services,” Dr. Tuckson said. “Physicians who are trying to care for our nation’s seniors – so many of whom are presenting real challenges in manging their care in an optimal way – those physicians and patients deserve the opportunity to use [telehealth] tools, and physicians deserve to be reimbursed for the appropriate use of those tools.”

Federal legislation to expand Medicare coverage for telehealth has previously failed. Most recently, Rep. Mike Thompson (D-Calif.) proposed H.R. 2948, the Medicare Telehealth Parity Act of 2015, a bill that would broaden Medicare telemedicine coverage to urban areas and cover more services. The bill has been referred to the House Ways and Means Committee’s Subcommittee on Health.

Coverage of telemedicine by all payers is especially necessary as the health care system shifts to a more value-based care structure, Dr. Marcin said. Telemedicine presents great opportunities for preventing illnesses, keeping patients out of the hospital, and lowering health costs, he said. However, financial incentives to utilize telemedicine in these ways is lacking.

“Even though these technologies have been proven to reduce overall health care costs, they result in lower payments to doctors and hospitals,” Dr. Marcin said. “There’s a malalignment with payments to both hospitals and doctors and what should be the goals of health care, which is to keep patients healthy.”

Coming Tuesday, Oct. 6: Can telemedicine expose you to legal risk?

On Twitter @legal_med

Emergency department personnel at a remote hospital called Dr. James P. Marcin regarding a baby who was just admitted with an upper respiratory infection. Because the patient had cyanotic congenital heart disease, the team was concerned she was too medically complex for their facility, and they were preparing to helicopter her to the pediatric intensive care unit at the University of California, Davis, Children’s Hospital in Sacramento.

But when Dr. Marcin examined the baby via a two-way video, he remembered the child from a previous visit. Although her oxygen levels were low, Dr. Marcin knew they were normal for her condition. Dr. Marcin spoke with the patient’s parents and after learning more about the patient’s symptoms, he was confident the child could remain at the small hospital. She was treated for the upper respiratory infection and later sent home where she improved, said Dr. Marcin, who leads the Pediatric Telemedicine Program at UC Davis.

Despite the positive outcome, Dr. Marcin’s claim was denied by the insurance company, he said.

“Had I not used telemedicine, that child would have been put in a helicopter, flown to our ICU, [and likely incurred] some $20,000 bill,” Dr. Marcin said in an interview. “I saved the insurance company $20,000, and then they ended up denying my 2 hours of critical care time. It’s discouraging.”

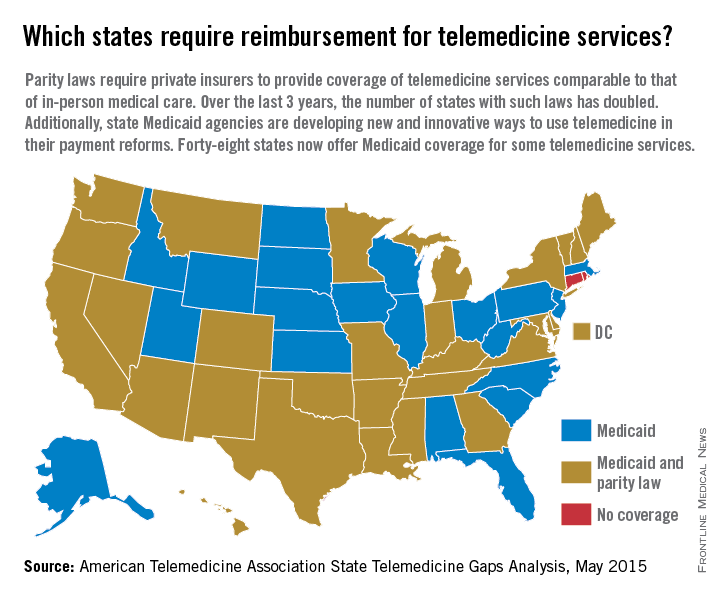

Reimbursement struggles are playing out in medical practices and hospitals across the country. While insurance coverage for telemedicine is growing, experts say payment remains one of the most pressing challenges. So far, 29 states and the District of Columbia have laws that require full parity of coverage and reimbursement for telemedicine services comparable to that of in-person services, according to the American Telemedicine Association (ATA). Medicaid programs in almost all (48) states require some form of compensation for telemedicine, according to a 2015 ATA report.

Payment parity for telemedicine has doubled in the last 2 years, noted Dr. Reed V. Tuckson, ATA president.

“We are seeing, on the side of the private insurance world, really exciting acceptance of telehealth services,” Dr. Tuckson said in an interview. There has been “really great movement forward.”

Enforcement of those parity laws can be spotty, said René Y. Quashie, a Washington health law attorney.

“It’s a mixed bag,” Mr. Quashie said in an interview. “In some states, enforcement is lax so you still have a lot of providers submitting claims that are not being paid or not being paid timely.”

State support equals payment success

In rural Wrightsville, Ga., Dr. Jean R. Sumner regularly gets paid to provide telemedicine. Georgia enacted its parity law in 2006 and has greatly embraced telemedicine capabilities, particularly for its rural populations, said Dr. Sumner, associate dean for rural health at Mercer University in Macon. Part of the success is because of the Georgia Partnership for TeleHealth, a statewide network that focuses on increasing access to care through telemedicine. Its hallmark is the state’s open access network, a web of access points based on existing telemedicine programs that enables secure health information exchange. The goal of the program is for all rural Georgians to access specialty care within 30 miles of their homes.

The state’s strong support of telemedicine contributes to payers taking the modality seriously and doctors getting paid for telemedicine care, Dr. Sumner said in an interview.

“Most insurers pay as long as the visit is equal or superior to an exam done in person,” she said. “It has to be quality care.”

Dr. Sumner also can bill a site fee when telemedicine technology is used at her practice, she said. If a patient visits her practice for a psychiatric consultation while Dr. Sumner is busy, for example, a nurse can connect the patient to a psychiatrist through the office’s telemedicine unit. The site fee is minimal, but it helps cover costs, she said.

In states that do not have parity laws, some larger health plans, such as Anthem and UnitedHealthcare, have proactively covered telemedicine services, said Dr. Peter Antall, president and medical director of American Well’s Online Care Group, a national telehealth service. Smaller health plans on the other hand, are sometimes willing to negotiate with providers and consider adding telemedicine services to a fee schedule, Dr. Antall said in an interview.

“I think we’re moving into a phase where reimbursement is normal or expected in telehealth,” he said. “We’re not quite there yet because there are so many health plans and, within the health plans, there are so many different products and subgroups. It’s still a process that needs to evolve.”

Government payers lag behind

Medicaid policies also vary from state by state. Some state programs cover telemedicine services similar to that of in-person treatment. Others limit coverage by technology or geographic area.

Medicare, by far, ranks the worst in paying physicians for telemedicine, experts said. Of $597 billion in total Medicare payments in 2014, 0.0023% was spent on telemedicine, according to data provided to the Robert J. Waters Center for Telehealth & e-Health Law.

“Unless you’re a patient that presents in a rural community, the Medicare telehealth benefit is not available,” said Mr. Quashie, who is part of the CTeL’s legal resource team. “Medicare is almost a no-go under fee-for-service for telehealth.”

CMS reimburses physicians for telemedicine only when the originating site is in a Health Professional Shortage Area or within a county outside a Metropolitan Statistical Area. The originating site must be a medical facility and not the patient’s home. CMS covers care only on an approved list of medical services.

In its 2016 proposed fee schedule, CMS recommended adding two new codes to its accepted telemedicine services, including codes for prolonged service inpatient care and end-stage renal disease–related services. However, the agency denied a handful of other services requested by the ATA and again, refused to end its patient site limitations.

“We are very concerned about Medicare’s decisions in terms of its ability and willingness to reimburse” telehealth services,” Dr. Tuckson said. “Physicians who are trying to care for our nation’s seniors – so many of whom are presenting real challenges in manging their care in an optimal way – those physicians and patients deserve the opportunity to use [telehealth] tools, and physicians deserve to be reimbursed for the appropriate use of those tools.”

Federal legislation to expand Medicare coverage for telehealth has previously failed. Most recently, Rep. Mike Thompson (D-Calif.) proposed H.R. 2948, the Medicare Telehealth Parity Act of 2015, a bill that would broaden Medicare telemedicine coverage to urban areas and cover more services. The bill has been referred to the House Ways and Means Committee’s Subcommittee on Health.

Coverage of telemedicine by all payers is especially necessary as the health care system shifts to a more value-based care structure, Dr. Marcin said. Telemedicine presents great opportunities for preventing illnesses, keeping patients out of the hospital, and lowering health costs, he said. However, financial incentives to utilize telemedicine in these ways is lacking.

“Even though these technologies have been proven to reduce overall health care costs, they result in lower payments to doctors and hospitals,” Dr. Marcin said. “There’s a malalignment with payments to both hospitals and doctors and what should be the goals of health care, which is to keep patients healthy.”

Coming Tuesday, Oct. 6: Can telemedicine expose you to legal risk?

On Twitter @legal_med

Emergency department personnel at a remote hospital called Dr. James P. Marcin regarding a baby who was just admitted with an upper respiratory infection. Because the patient had cyanotic congenital heart disease, the team was concerned she was too medically complex for their facility, and they were preparing to helicopter her to the pediatric intensive care unit at the University of California, Davis, Children’s Hospital in Sacramento.

But when Dr. Marcin examined the baby via a two-way video, he remembered the child from a previous visit. Although her oxygen levels were low, Dr. Marcin knew they were normal for her condition. Dr. Marcin spoke with the patient’s parents and after learning more about the patient’s symptoms, he was confident the child could remain at the small hospital. She was treated for the upper respiratory infection and later sent home where she improved, said Dr. Marcin, who leads the Pediatric Telemedicine Program at UC Davis.

Despite the positive outcome, Dr. Marcin’s claim was denied by the insurance company, he said.

“Had I not used telemedicine, that child would have been put in a helicopter, flown to our ICU, [and likely incurred] some $20,000 bill,” Dr. Marcin said in an interview. “I saved the insurance company $20,000, and then they ended up denying my 2 hours of critical care time. It’s discouraging.”

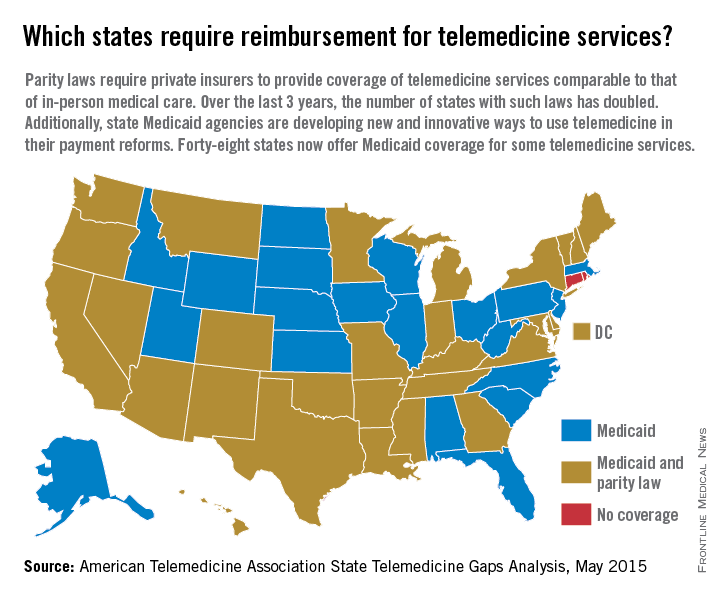

Reimbursement struggles are playing out in medical practices and hospitals across the country. While insurance coverage for telemedicine is growing, experts say payment remains one of the most pressing challenges. So far, 29 states and the District of Columbia have laws that require full parity of coverage and reimbursement for telemedicine services comparable to that of in-person services, according to the American Telemedicine Association (ATA). Medicaid programs in almost all (48) states require some form of compensation for telemedicine, according to a 2015 ATA report.

Payment parity for telemedicine has doubled in the last 2 years, noted Dr. Reed V. Tuckson, ATA president.

“We are seeing, on the side of the private insurance world, really exciting acceptance of telehealth services,” Dr. Tuckson said in an interview. There has been “really great movement forward.”

Enforcement of those parity laws can be spotty, said René Y. Quashie, a Washington health law attorney.

“It’s a mixed bag,” Mr. Quashie said in an interview. “In some states, enforcement is lax so you still have a lot of providers submitting claims that are not being paid or not being paid timely.”

State support equals payment success

In rural Wrightsville, Ga., Dr. Jean R. Sumner regularly gets paid to provide telemedicine. Georgia enacted its parity law in 2006 and has greatly embraced telemedicine capabilities, particularly for its rural populations, said Dr. Sumner, associate dean for rural health at Mercer University in Macon. Part of the success is because of the Georgia Partnership for TeleHealth, a statewide network that focuses on increasing access to care through telemedicine. Its hallmark is the state’s open access network, a web of access points based on existing telemedicine programs that enables secure health information exchange. The goal of the program is for all rural Georgians to access specialty care within 30 miles of their homes.

The state’s strong support of telemedicine contributes to payers taking the modality seriously and doctors getting paid for telemedicine care, Dr. Sumner said in an interview.

“Most insurers pay as long as the visit is equal or superior to an exam done in person,” she said. “It has to be quality care.”

Dr. Sumner also can bill a site fee when telemedicine technology is used at her practice, she said. If a patient visits her practice for a psychiatric consultation while Dr. Sumner is busy, for example, a nurse can connect the patient to a psychiatrist through the office’s telemedicine unit. The site fee is minimal, but it helps cover costs, she said.

In states that do not have parity laws, some larger health plans, such as Anthem and UnitedHealthcare, have proactively covered telemedicine services, said Dr. Peter Antall, president and medical director of American Well’s Online Care Group, a national telehealth service. Smaller health plans on the other hand, are sometimes willing to negotiate with providers and consider adding telemedicine services to a fee schedule, Dr. Antall said in an interview.

“I think we’re moving into a phase where reimbursement is normal or expected in telehealth,” he said. “We’re not quite there yet because there are so many health plans and, within the health plans, there are so many different products and subgroups. It’s still a process that needs to evolve.”

Government payers lag behind

Medicaid policies also vary from state by state. Some state programs cover telemedicine services similar to that of in-person treatment. Others limit coverage by technology or geographic area.

Medicare, by far, ranks the worst in paying physicians for telemedicine, experts said. Of $597 billion in total Medicare payments in 2014, 0.0023% was spent on telemedicine, according to data provided to the Robert J. Waters Center for Telehealth & e-Health Law.

“Unless you’re a patient that presents in a rural community, the Medicare telehealth benefit is not available,” said Mr. Quashie, who is part of the CTeL’s legal resource team. “Medicare is almost a no-go under fee-for-service for telehealth.”

CMS reimburses physicians for telemedicine only when the originating site is in a Health Professional Shortage Area or within a county outside a Metropolitan Statistical Area. The originating site must be a medical facility and not the patient’s home. CMS covers care only on an approved list of medical services.

In its 2016 proposed fee schedule, CMS recommended adding two new codes to its accepted telemedicine services, including codes for prolonged service inpatient care and end-stage renal disease–related services. However, the agency denied a handful of other services requested by the ATA and again, refused to end its patient site limitations.

“We are very concerned about Medicare’s decisions in terms of its ability and willingness to reimburse” telehealth services,” Dr. Tuckson said. “Physicians who are trying to care for our nation’s seniors – so many of whom are presenting real challenges in manging their care in an optimal way – those physicians and patients deserve the opportunity to use [telehealth] tools, and physicians deserve to be reimbursed for the appropriate use of those tools.”

Federal legislation to expand Medicare coverage for telehealth has previously failed. Most recently, Rep. Mike Thompson (D-Calif.) proposed H.R. 2948, the Medicare Telehealth Parity Act of 2015, a bill that would broaden Medicare telemedicine coverage to urban areas and cover more services. The bill has been referred to the House Ways and Means Committee’s Subcommittee on Health.

Coverage of telemedicine by all payers is especially necessary as the health care system shifts to a more value-based care structure, Dr. Marcin said. Telemedicine presents great opportunities for preventing illnesses, keeping patients out of the hospital, and lowering health costs, he said. However, financial incentives to utilize telemedicine in these ways is lacking.

“Even though these technologies have been proven to reduce overall health care costs, they result in lower payments to doctors and hospitals,” Dr. Marcin said. “There’s a malalignment with payments to both hospitals and doctors and what should be the goals of health care, which is to keep patients healthy.”

Coming Tuesday, Oct. 6: Can telemedicine expose you to legal risk?

On Twitter @legal_med