User login

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), also known as acne inversa or Verneuil disease, is a chronic, recurrent, inflammatory occlusive disease affecting the terminal follicular epithelium in apocrine gland–bearing skin areas.1 HS manifests as painful nodules, abscesses, fistulas, and scarring and often has a severe psychological impact on the affected patient.2

When HS was first identified in the 1800s, it was believed to result from a dysfunction of the sweat glands.3 In 1939, scientists identified the true cause: follicular occlusion.3

Due to its chronic nature, heterogeneity in presentation, and apparent low prevalence,4 HS is considered an orphan disease.5 Over the past 10 years, there has been a surge in HS research—particularly in medical management—which has provided a better understanding of this condition.6,7

In this review, we discuss the most updated evidence regarding the diagnosis and treatment of HS to guide the family physician (FP)’s approach to managing this debilitating disease. But first, we offer a word about the etiology and pathophysiology of the condition.

3 events set the stage for hidradenitis suppurativa

Although the exact cause of HS is still unknown, some researchers have hypothesized that HS results from a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental and lifestyle factors.8-12 The primary mechanism of HS is the obstruction of the terminal follicular epithelium by a keratin plug.1,13,14 A systematic review of molecular inflammatory pathways involved in HS divides the pathogenesis of HS into 3 events: follicular occlusion followed by dilation, follicular rupture and inflammatory response, and chronic inflammatory state with sinus tracts.8

An underreported condition

HS is often underreported and misdiagnosed.4,15 Globally, the prevalence of HS varies from < 1% to 4%.15,16 A systematic review with meta-analysis showed a higher prevalence of HS in females compared to males in American and European populations.17 In the United States, the overall frequency of HS is 0.1%, or 98 per 100,000 persons.16 The prevalence of HS is highest among patients ages 30 to 39 years; there is decreased prevalence in patients ages 55 years and older.16,18

Who is at heightened risk?

Recent research has shown a relationship between ethnicity and HS.16,19,20 African American and biracial groups (defined as African American and White) have a 3-fold and 2-fold greater prevalence of HS, respectively, compared to White patients.16 However, the prevalence of HS in non-White ethnic groups may be underestimated in clinical trials due to a lack of representation and subgroup analyses based on ethnicity, which may affect generalizability in HS recommendations.21

Continue to: Genetic predisposition

Genetic predisposition. As many as 40% of patients with HS report having at least 1 affected family member. A positive family history of HS is associated with earlier onset, longer disease duration, and severe disease.22 HS is genetically heterogeneous, and several mutations (eg, gamma secretase, PSTPIP1, PSEN1 genes) have been identified in patients and in vitro as the cause of dysregulation of epidermal proliferation and differentiation, immune dysregulation, and promotion of amyloid formation.8,23-25

Obesity and metabolic risk factors. There is a strong relationship between HS and obesity. As many as 70% of patients with HS are obese, and 9% to 40% have metabolic syndrome.12,18,26-28 Obesity is associated with maceration and mechanical stress, increased fragility of the dermo-epidermal junction, changes in cutaneous blood flow, and subdermal fat inflammation—all of which favor the pathophysiology of HS.29,30

Smoking. Tobacco smoking is associated with severe HS and a lower chance of remission.12 Population-based studies have shown that as many as 90% of patients with HS have a history of smoking ≥ 20 packs of cigarettes per year.1,12,18,31,32 The nicotine and thousands of other chemicals present in cigarettes trigger keratinocytes and fibroblasts, resulting in epidermal hyperplasia, infundibular hyperkeratosis, excessive cornification, and dysbiosis.8,23,24

Hormones. The exact role sex hormones play in the pathogenesis of HS remains unclear.8,32 Most information is based primarily on small studies looking at antiandrogen treatments, HS activity during the menstrual cycle and pregnancy, HS exacerbation related to androgenic effects of hormonal contraception, and the association of HS with metabolic-endocrine disorders (eg, polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]).8,33

Androgens induce hyperkeratosis that may lead to follicular occlusion—the hallmark of HS pathology.34 A systematic review looking at the role of androgen and estrogen in HS found that while some patients with HS have elevated androgen levels, most have androgen and estrogen levels within normal range.35 Therefore, increased peripheral androgen receptor sensitivity has been hypothesized as the mechanism of action contributing to HS manifestation.34

Continue to: Host-defense defects

Host-defense defects. HS shares a similar cytokine profile with other well-established immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including pyoderma gangrenosum (PG)36,37 and Crohn disease.38-40 HS is characterized by the expression of several immune mediators, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), interleukin-1 alpha (IL-1 alpha), IL-1 beta, IL-8, IL-17, and the IL-23/T helper 17 pathway, all of which are upregulated in other inflammatory diseases and also result in an abnormal innate immune response.8,24 The recently described clinical triad of PG, acne, and HS (PASH) and the tetrad of pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne, and HS (PAPASH) further support the role of immune dysregulation in the pathogenesis of HS.40 Nonetheless, further studies are needed to determine the exact pathways of cytokine effect in HS.41

Use these criteria to make the diagnosis

The US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations (HSF) guidelines base the clinical diagnosis of HS on the following criteria2:

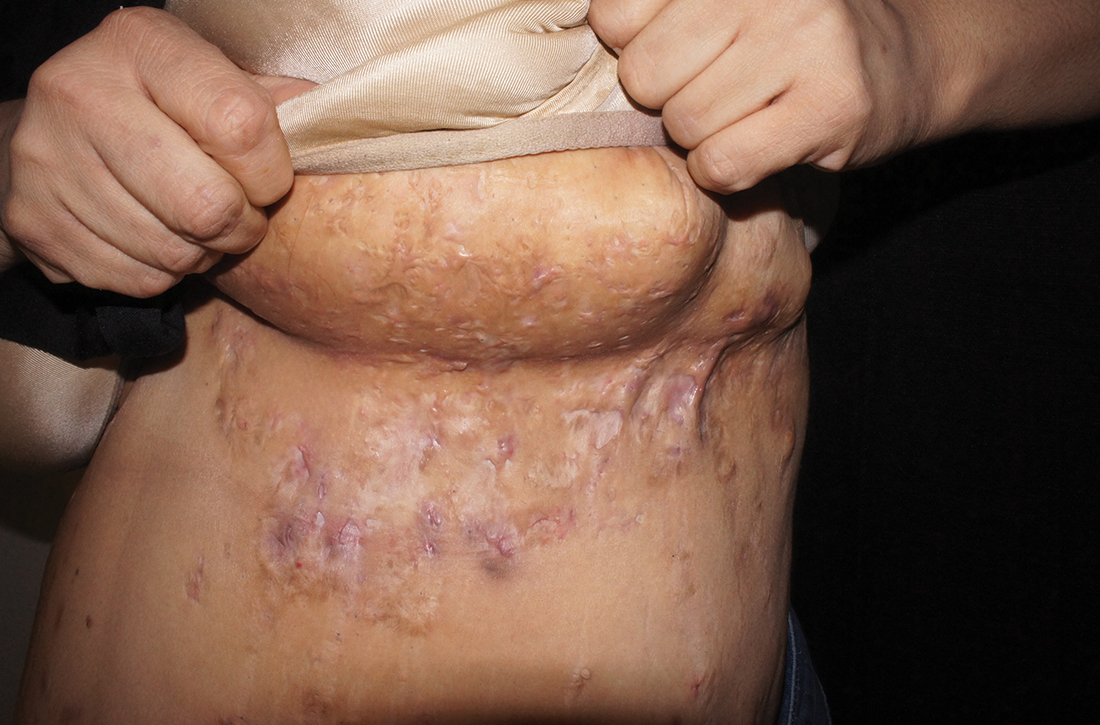

- Typical HS lesions: Erythematous skin lesions; inflamed, deep-seated painful nodules; “tombstone” double-ended comedones; sinus tracts; scarring; deformity. FIGURES 1A-1E show typical lesions seen in patients with HS.

- Typical locations: Intertriginous regions—apocrine gland–containing areas in axilla, groin, perineal region, buttocks, gluteal cleft, and mammary folds; beltline and waistband areas; areas of skin compression and friction.

- Recurrence and chronicity: Recurrent painful or suppurating lesions that appear more than twice in a 6-month period.2,41-43

Patients with HS usually present with painful recurrent abscesses and scarring and often report multiple visits to the emergency department for drainage or failed antibiotic treatment for abscesses.15,44

Ask patients these 2 questions. Vinding et al45 developed a survey for the diagnosis of HS using 2 simple questions based on the 3 criteria established by the HSF:

- “Have you had an outbreak of boils during the last 6 months?” and

- “Where and how many boils have you had?” (This question includes a list of the typical HS locations—eg, axilla, groin, genitals, area under breast.)

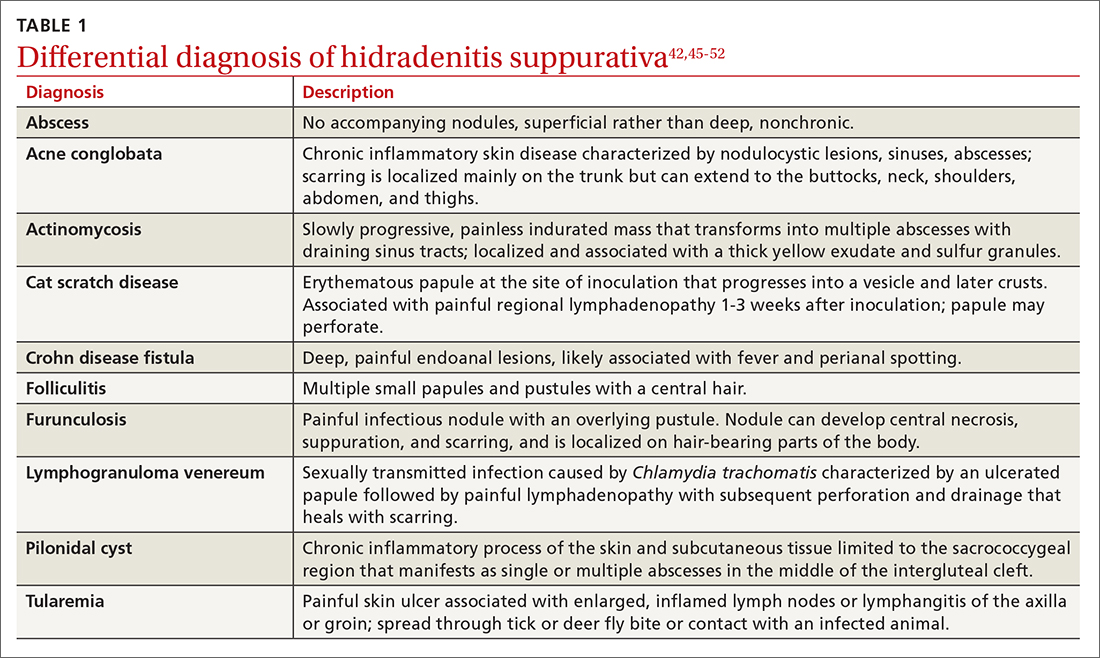

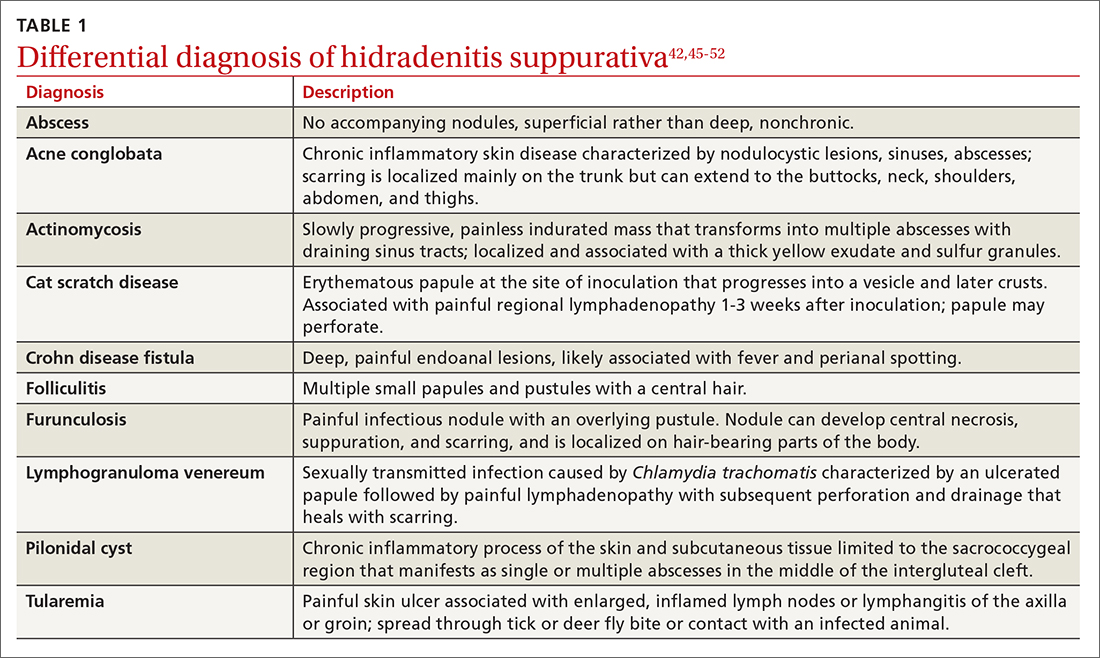

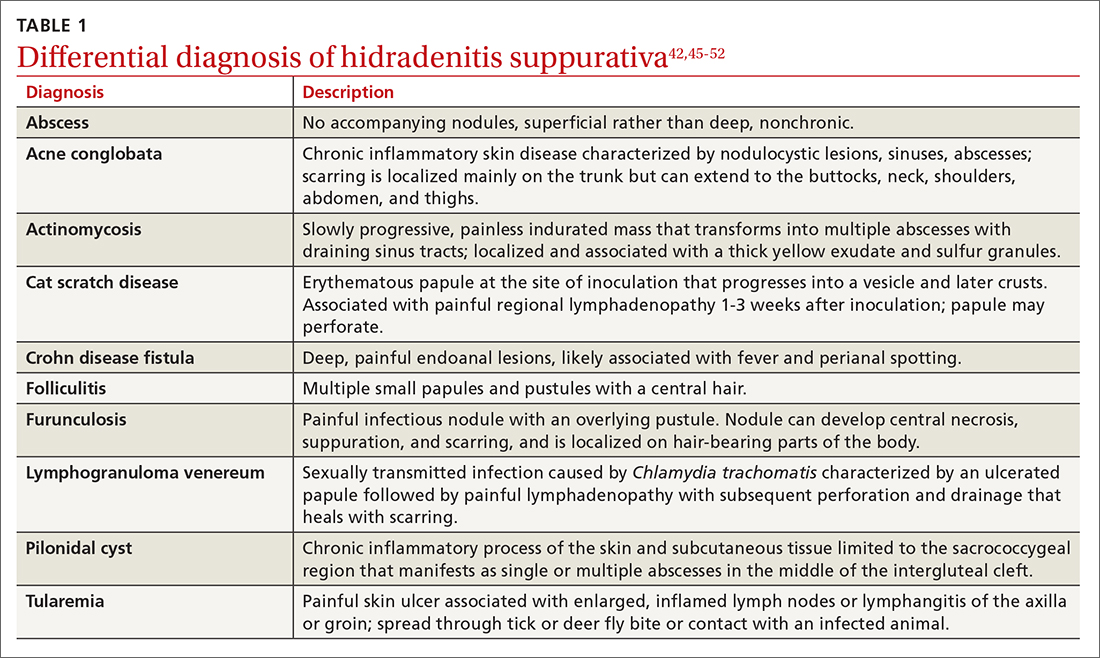

In their questionnaire, Vinding et al45 found that an affirmative answer to Question 1 and reports of > 2 boils in response to Question 2 correlated to a sensitivity of 90%, specificity of 97%, positive predictive value of 96%, and negative predictive value of 92% for the diagnosis of HS. The differential diagnosis of HS is summarized in TABLE 1.42,45-52

Continue to: These tools can help you to stage hidradenitis suppurativa

These tools can help you to stage hidradenitis suppurativa

Multiple tools are available to assess the severity of HS.53 We will describe the Hurley staging system and the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System (IHS4). Other diagnostic tools, such as the Sartorius score and the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Physician’s Global Assessment Scale (HS-PGA), can be time-consuming and challenging to interpret, limiting their use in the clinical setting.2,54

Hurley staging system (available at www.hsdiseasesource.com/hs-disease-staging) considers the presence of nodules, abscesses, sinus tracts, and scarring affecting an entire anatomical area.13,55 This system is most useful as a rapid classification tool for patients with HS in the clinical setting but should not be used to assess clinical response.2,13,56

The IHS4 (available at https://online library.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjd.15748) is a validated and easy-to-use tool for assessing HS and guiding the therapeutic strategy in clinical practice.54 With IHS4, the clinician must calculate the following:

- total number of nodules > 10 mm in diameter

- total number of abscesses multiplied by 2, and

- total number of draining tunnels (fistulae/sinuses) multiplied by 4.

Mild HS is defined as a score ≤ 3 points; moderate HS, 4 to 10 points; and severe HS, ≥ 11 points.54

No diagnostic tests, but ultrasound may be helpful

There are currently no established biological markers or specific tests for diagnosing HS.15 Ultrasound is emerging as a tool to assess dermal thickness, hair follicle morphology, and number and extent of fluid collections. Two recent studies showed that pairing clinical assessment with ultrasound findings improves accuracy of scoring in 84% of cases.57,58 For patients with severe HS, skin biopsy can be considered to rule out squamous cell carcinoma. Cultures, however, have limited utility except for suspected superimposed bacterial infection.2

Continue to: Screening for comorbidities

Screening for comorbidities

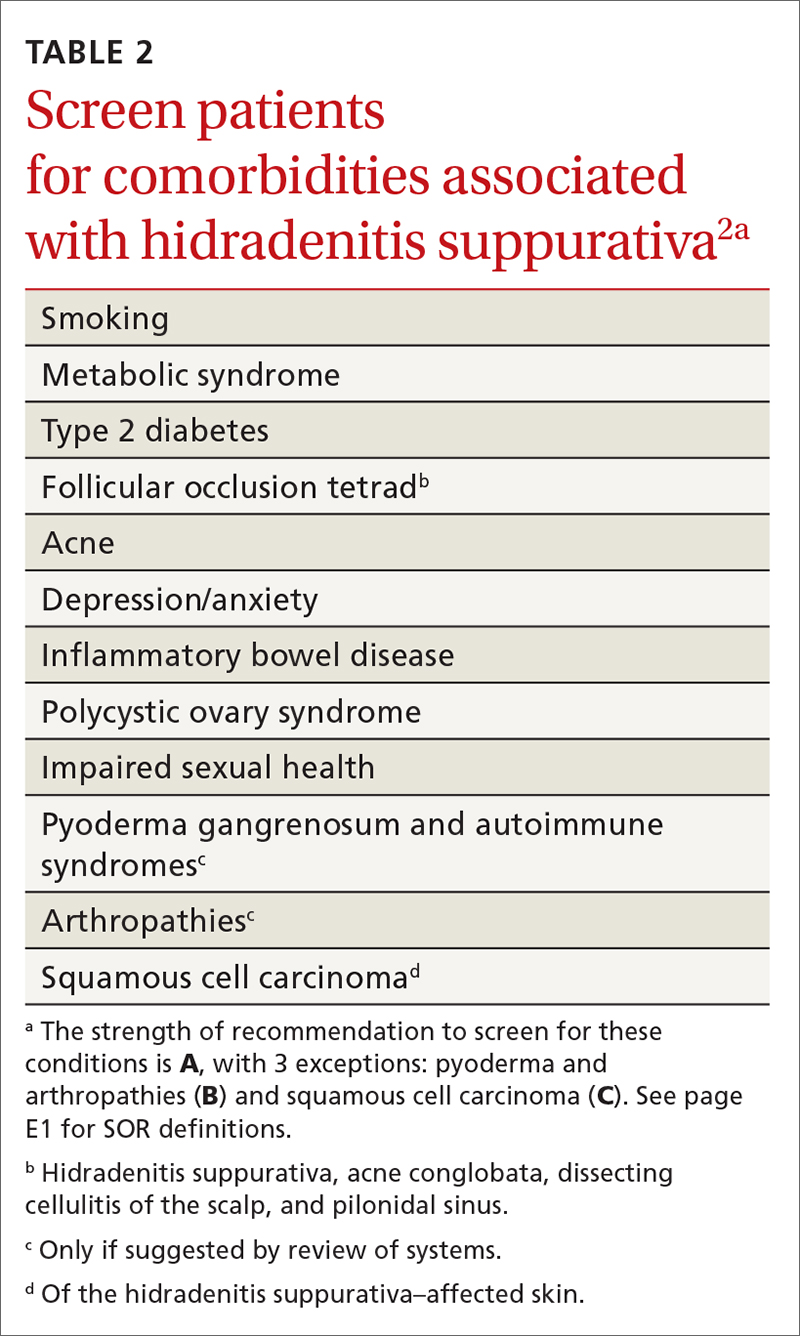

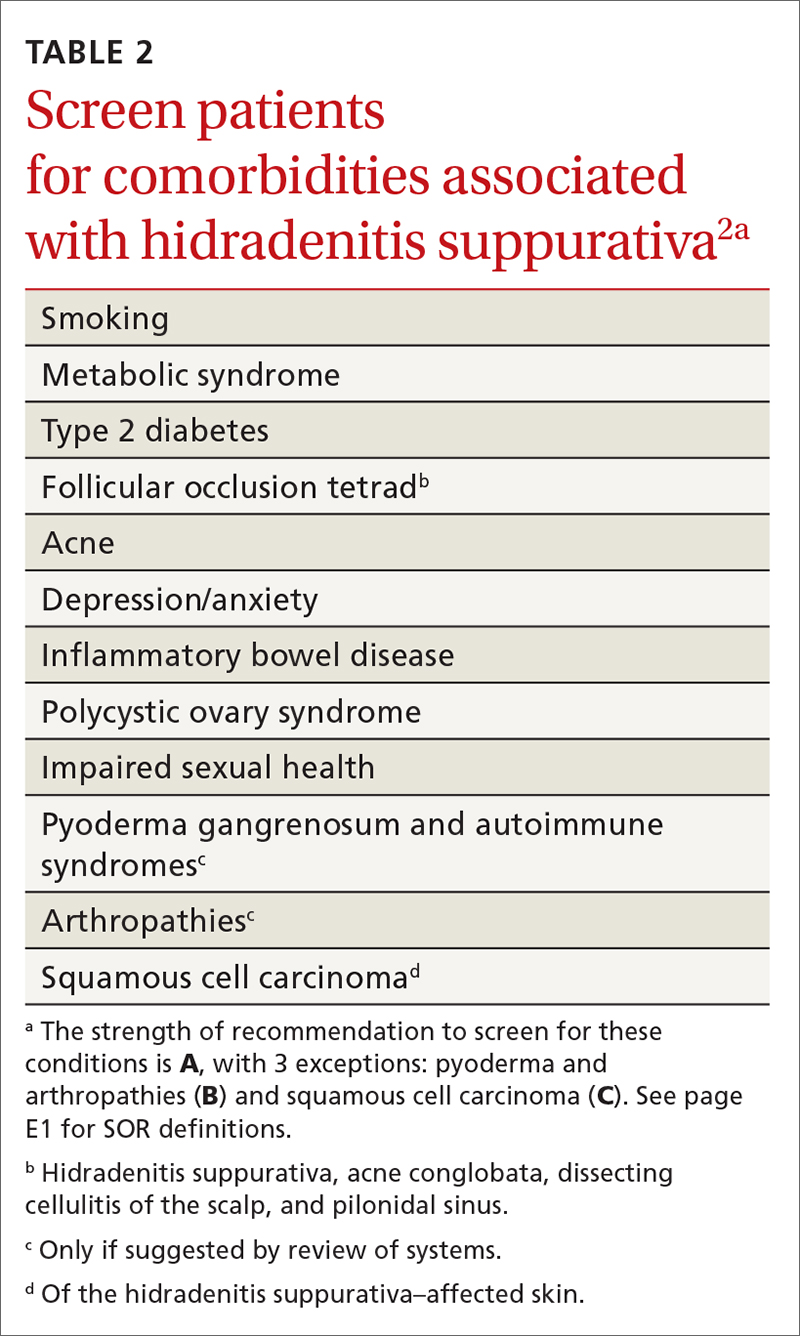

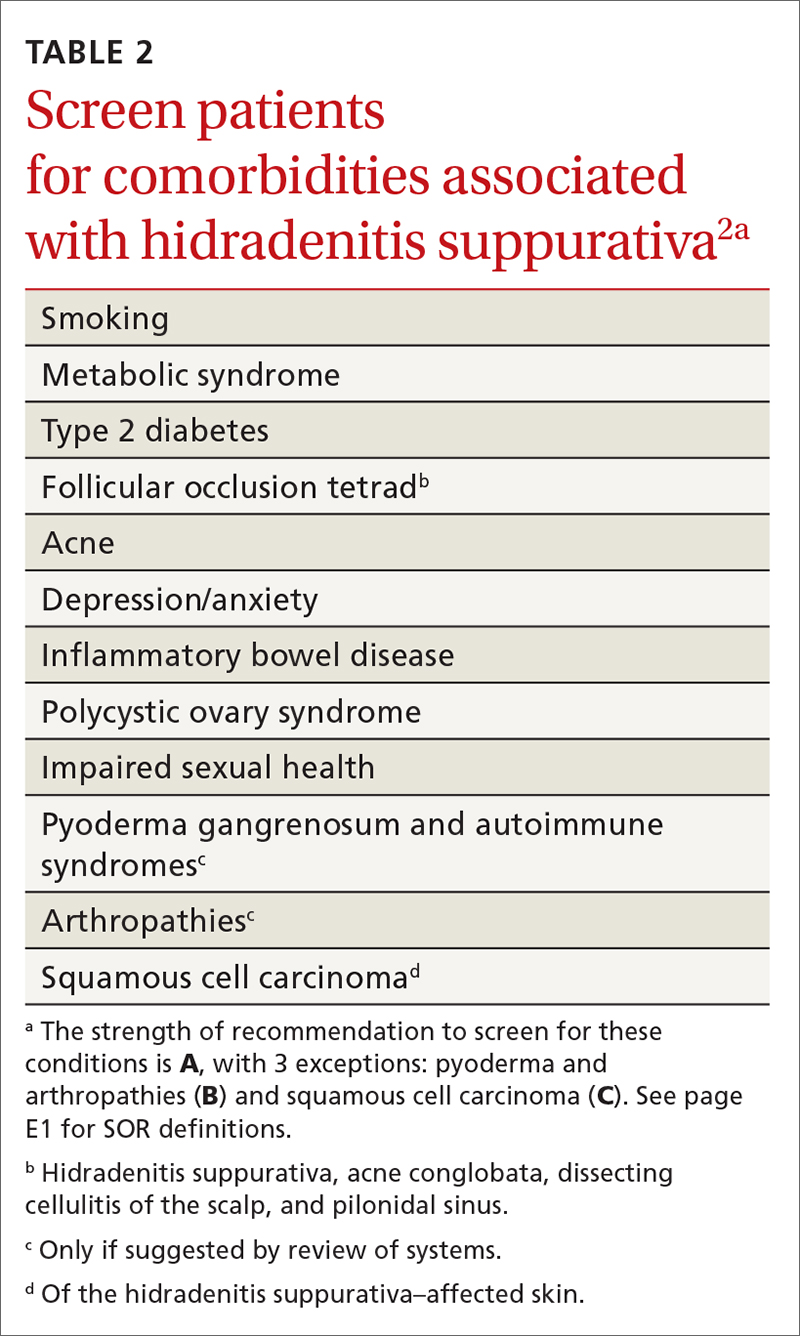

HSF recommends clinicians screen patients for comorbidities associated with HS (TABLE 2).2 Overall, screening patients for active and past history of smoking is strongly recommended, as is screening for metabolic syndrome, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes (1.5- to 3-fold greater risk of type 2 diabetes in HS patients), and PCOS (3-fold greater risk).2,26,27,59 Screening patients for depression and anxiety is also routinely recommended.2 However, the authors of this article strongly recommend screening all patients with HS for psychiatric comorbidities, as research has shown a 2-fold greater risk of depression and anxiety, social isolation, and low self-esteem that severely limits quality of life (QOL) in this patient population.60,61

Management

Treat existing lesions, reduce formation of new ones

The main goals of treatment for patients with HS are to treat existing lesions and reduce associated symptoms, reduce the formation of new lesions, and minimize associated psychological morbidity.15 FPs play an important role in the early diagnosis, treatment, and comprehensive care of patients with HS. This includes monitoring patients, managing comorbidities, making appropriate referrals to dermatologists, and coordinating the multidisciplinary care that patients with HS require.

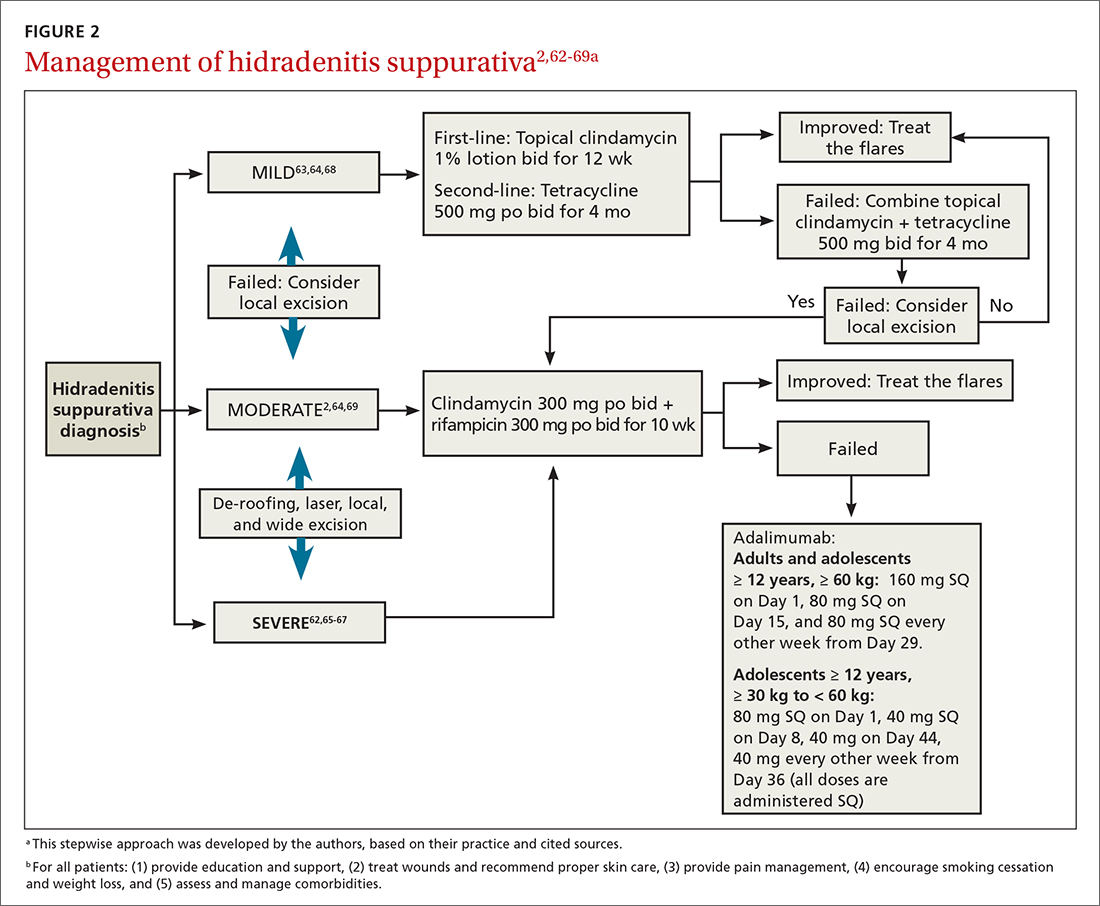

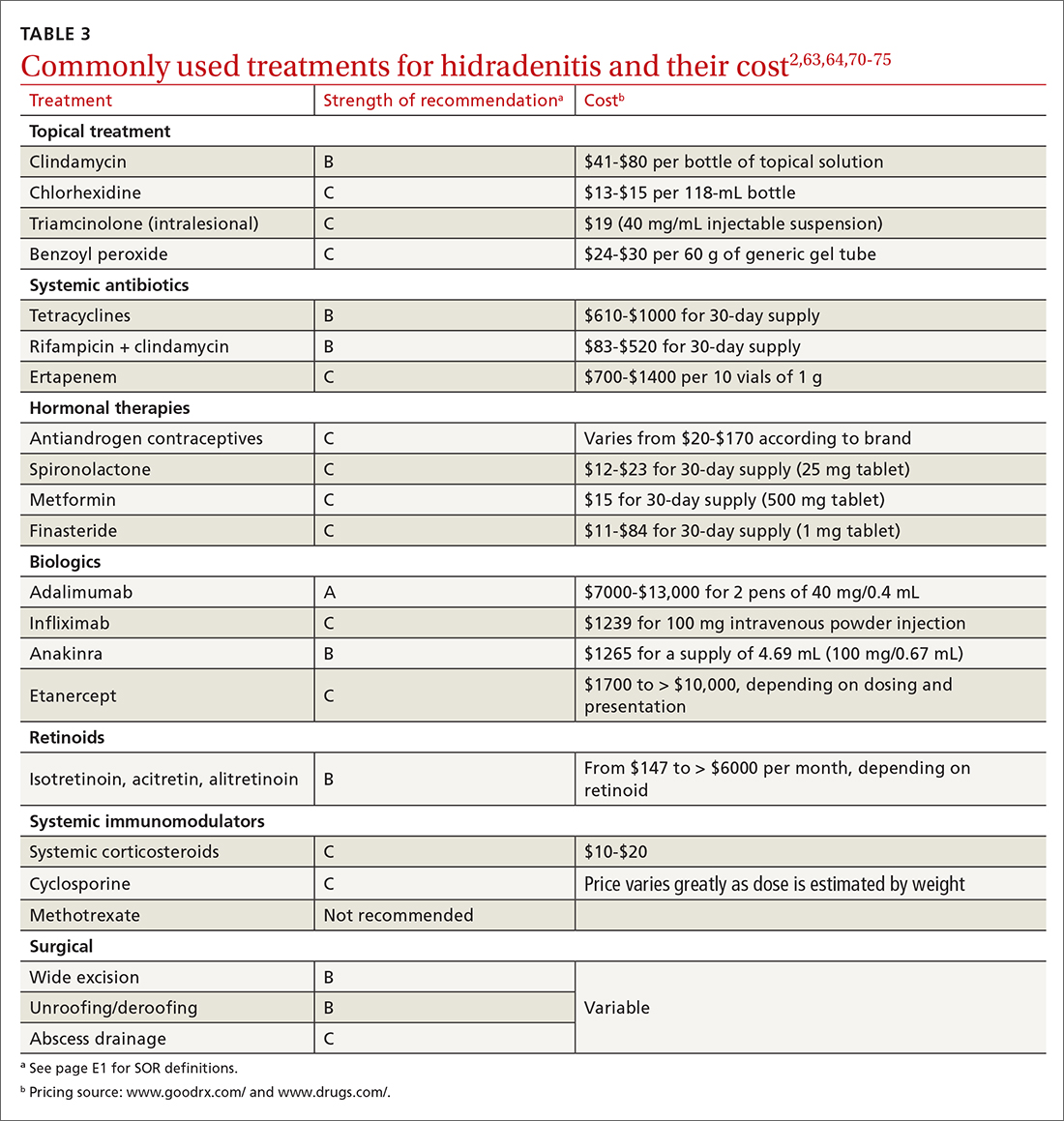

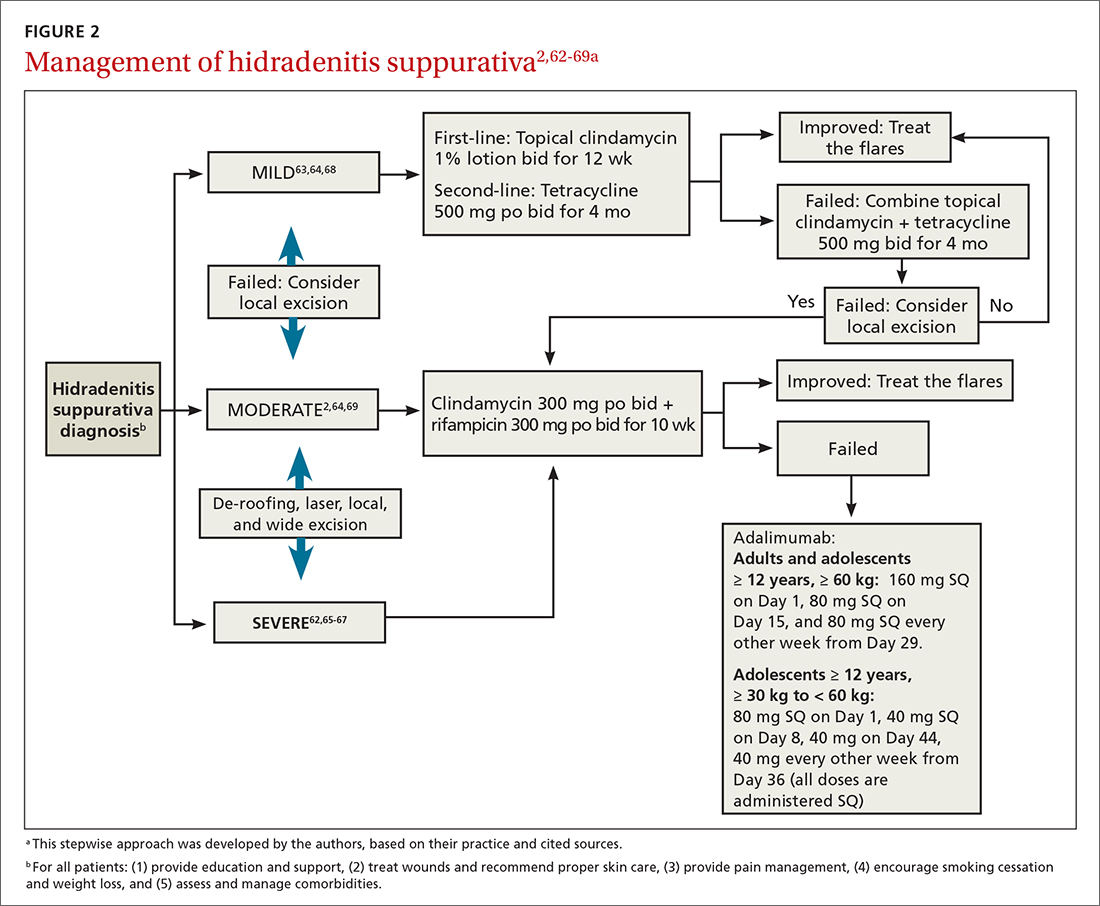

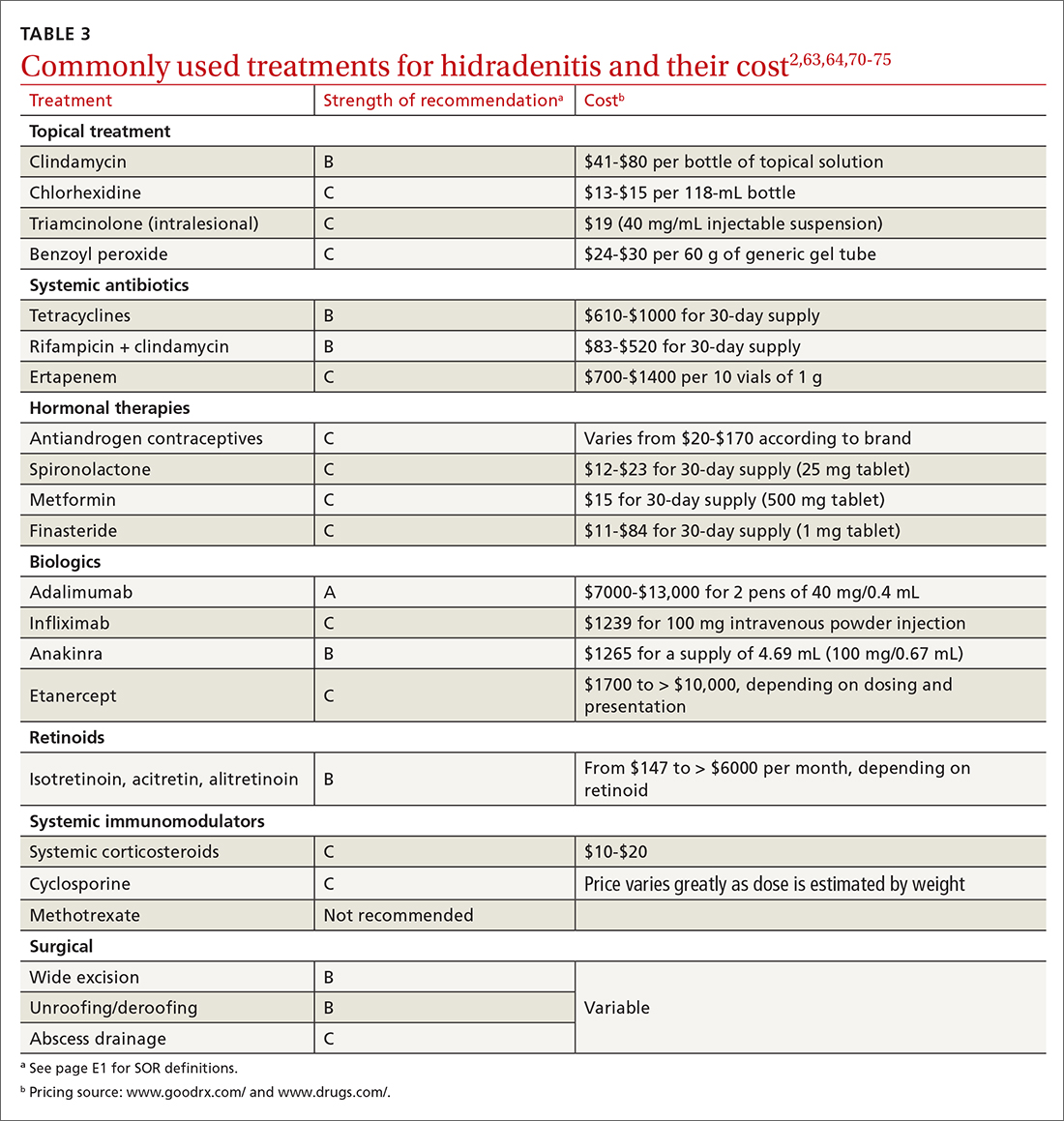

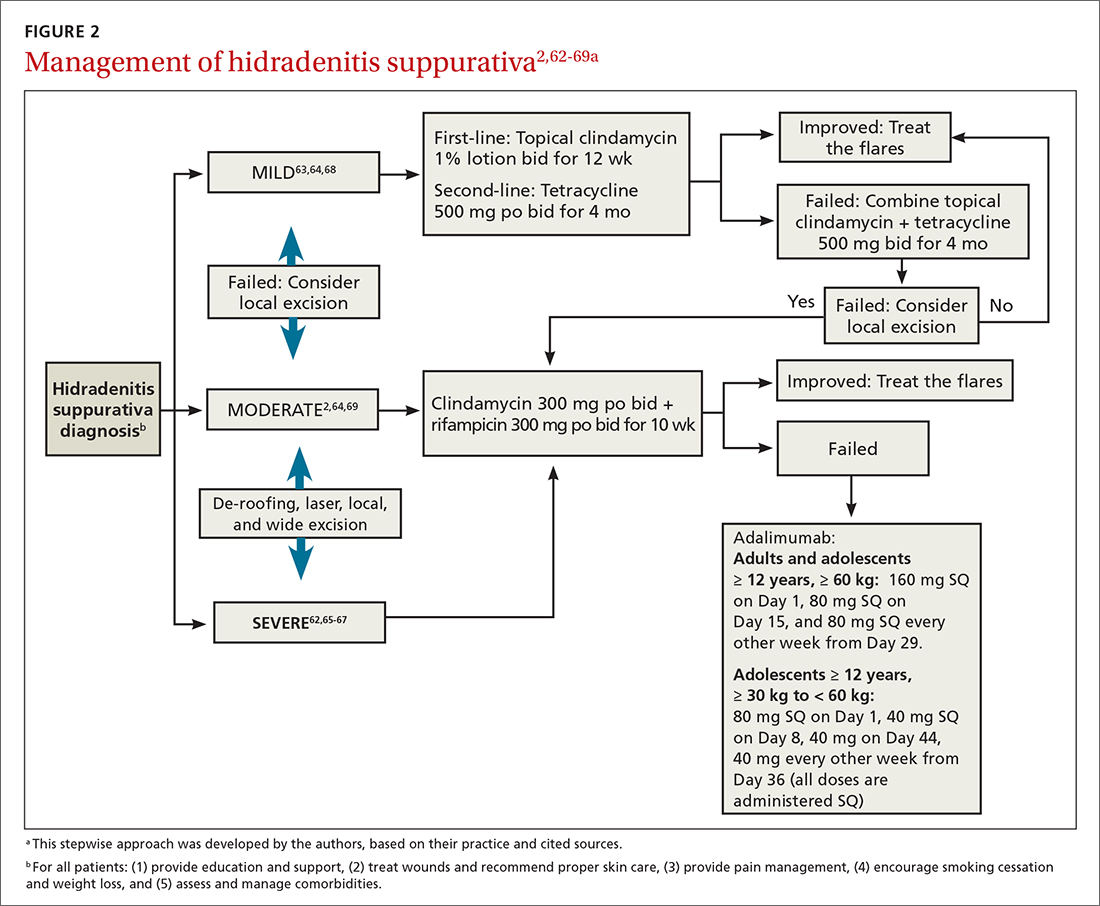

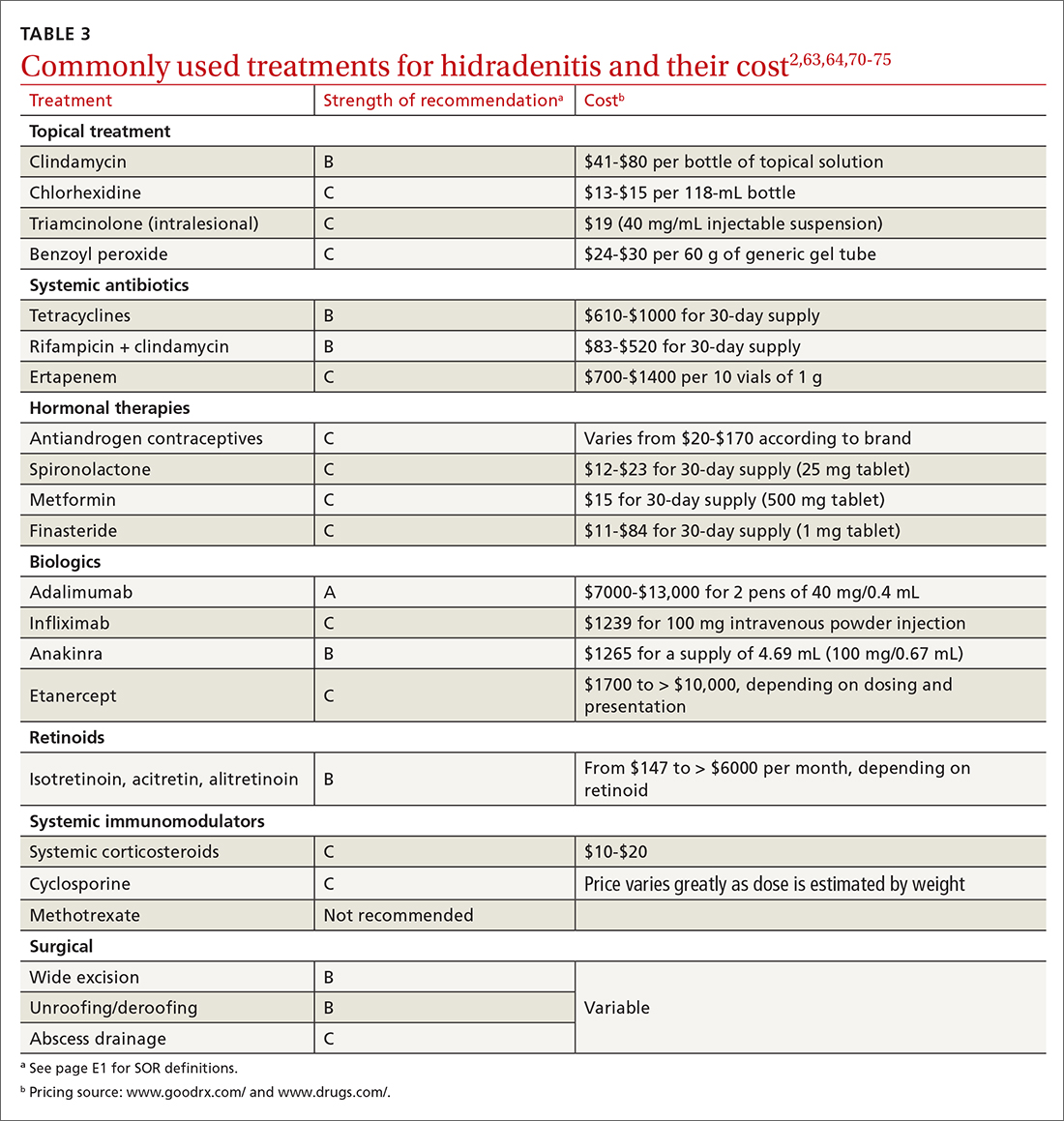

A systematic review identified more than 50 interventions used to treat HS, most based on small observational studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with a high risk of bias.62 FIGURE 22,62-69 provides an evidence-based treatment algorithm for HS, and TABLE 32,63,64,70-75 summarizes the most commonly used treatments.

Biologic agents

Adalimumab (ADA) is a fully human immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody that binds to TNF-alpha, neutralizes its bioactivity, and induces apoptosis of TNF-expressing mononuclear cells. It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for active refractory moderate and severe HS.62,65 Several double-blinded RCTs, including PIONEER I and PIONEER II, studied the effectiveness of ADA for HS and found significant clinical responses at Week 12, 50% reduction in abscess and nodule counts, no increase in abscesses or draining fistulas at Week 12, and sustained improvement in lesion counts, pain, and QOL.66,67,76

IL-1 and IL-23 inhibitors. The efficacy of etanercept and golimumab (anti-TNF), as well as anakinra (IL-1 inhibitor) and ustekinumab (IL-1/IL-23 inhibitor), continue to be investigated with variable results; they are considered second-line treatment for active refractory moderate and severe HS after ADA.65,77-80 Infliximab (IL-1 beta inhibitor) has shown no effect on reducing disease severity.70Compared to other treatments, biologic therapy is associated with higher costs (TABLE 3),2,63,64,70-75 an increased risk for reactivation of latent infections (eg, tuberculosis, herpes simplex, and hepatitis C virus [HCV], and B [HBV]), and an attenuated response to vaccines.81 Prior to starting biologic therapy, FPs should screen patients with HS for tuberculosis and HBV, consider HIV and HCV screening in at-risk patients, and optimize the immunization status of the patient.82,83 While inactivated vaccines can be administered without discontinuing biologic treatment, patients should avoid live-attenuated vaccines while taking biologics.83

Continue to: Antibiotic therapy

Antibiotic therapy

Topical antibiotics are considered first-line treatment for mild and moderate uncomplicated HS.63,64 Clindamycin 1%, the only topical antibiotic studied in a small double-blind RCT of patients with Hurley stage I and stage II HS, demonstrated significant clinical improvement after 12 weeks of treatment (twice- daily application), compared to placebo.84 Topical clindamycin is also recommended to treat flares in patients with mild disease.2,64

Oral antibiotics. Tetracycline (500 mg twice daily for 4 months) is considered a second-line treatment for patients with mild HS.64,68 Doxycycline (200 mg/d for 3 months) may also be considered as a second-line treatment in patients with mild disease.85

Combination oral clindamycin (300 mg) and rifampicin (300 mg) twice daily for 10 weeks is recommended as first-line treatment for patients with moderate HS.2,64,69 Combination rifampin (300 mg twice daily), moxifloxacin (400 mg/d), and metronidazole (500 mg three times a day) is not routinely recommended due to increased risk of toxicity.2

Ertapenem (1 g intravenously daily for 6 weeks) is supported by lower-level evidence as a third-line rescue therapy option and as a bridge to surgery; however, limitations for home infusions, costs, and concerns for antibiotic resistance limit its use.2,86

Corticosteroids and systemic immunomodulators

Intralesional triamcinolone (2-20 mg) may be beneficial in the early stages of HS, although its use is based on a small prospective open study of 33 patients.87 A recent double-blind placebo-controlled RCT comparing varying concentrations of intralesional triamcinolone (10 mg/mL and 40 mg/mL) vs normal saline showed no statistically significant difference in inflammatory clearance, pain reduction, or patient satisfaction.88

Continue to: Short-term systemic corticosteroid tapers...

Short-term systemic corticosteroid tapers (eg, prednisone, starting at 0.5-1 mg/kg) are recommended to treat flares. Long-term corticosteroids and cyclosporine are reserved for patients with severe refractory disease; however, due to safety concerns, their regular use is strongly discouraged.63,64,85 There is limited evidence to support the use of methotrexate for severe refractory disease, and its use is not recommended.63

Hormonal therapy

The use of hormonal therapy for HS is limited by the low-quality evidence (eg, anecdotal evidence, small retrospective analyses, uncontrolled trials).33,63 The only exception is a small double-blind controlled crossover trial from 1986 showing that the antiandrogen effects of combination oral contraceptives (ethinyloestradiol 50 mcg/cyproterone acetate in a reverse sequential regimen and ethinyloestradiol 50 mcg/norgestrel 500 mcg) improved HS lesions.89

Spironolactone, an antiandrogen diuretic, has been studied in small case report series with a high risk for bias. It is used mainly in female patients with mild or moderate disease, or in combination with other agents in patients with severe HS. Further research is needed to determine its utility in the treatment of HS.63,90,91

Metformin, alone or in combination with other therapies (dapsone, finasteride, liraglutide), has been analyzed in small prospective studies of primarily female patients with different severities of HS, obesity, and PCOS. These studies have shown improvement in lesions, QOL, and reduction of workdays lost.92,93

Finasteride. Studies have shown finasteride (1.25-5 mg/d) alone or in combination with other treatments (metformin, liraglutide, levonorgestrel-ethinyl estradiol, and dapsone) provided varying degrees of resolution or improvement in patients with severe and advanced HS. Finasteride has been used for 4 to 16 weeks with a good safety profile.92,94-96

Continue to: Retinoids

Retinoids

Acitretin, alitretinoin, and isotretinoin have been studied in small retrospective studies to manage HS, with variable results.97-99 Robust prospective studies are needed. Retinoids, in general, should be considered as a second- or third-line treatment for moderate to severe HS.63

Surgical intervention

Surgical interventions, which should be considered in patients with widespread mild, moderate, or severe disease, are associated with improved daily activity and work productivity.100 Incision and drainage should be avoided in patients with HS, as this technique does not remove the affected follicles and is associated with 100% recurrence.101

Wide excision is the preferred surgical technique for patients with Hurley stage II and stage III HS; it is associated with lower recurrence rates (13%) compared to local excision (22%) and deroofing (27%).102 Secondary intention healing is the most commonly chosen method, based on lower recurrence rates than primary closure.102

STEEP and laser techniques. The skin-tissue-sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling (STEEP) procedure involves successive tangential excision of affected tissue until the epithelized bottom of the sinus tracts has been reached. This allows for the removal of fibrotic tissue and the sparing of the deep subcutaneous fat. STEEP is associated with 30% of relapses after 43 months.71

Laser surgery has also been studied in patients with Hurley stage II and stage III HS. The most commonly used lasers for HS are the 1064-nm neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd: YAG) and the carbon dioxide laser; they have been shown to reduce disease severity in inguinal, axillary, and inflammatory sites.72-74

Pain management: Start with lidocaine, NSAIDs

There are few studies about HS-associated pain management.103 For acute episodes, short-acting nonopioid local treatment with lidocaine, topical or oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and acetaminophen are preferred. Opioids should be reserved for moderate-to-severe pain that has not responded to other analgesics. Adjuvant therapy with pregabalin, gabapentin, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors can also be considered for the comanagement of pain and depression.62,104

Consider this tool to measure treatment response

The HS clinical response (HiSCR) tool is an outcome measure used to evaluate treatment outcomes. The tool uses an HS-specific binary score with the following criteria:

- ≥ 50% reduction in the number of inflammatory nodules;

- no increase in the number of abscesses; and

- no increase in the number of draining fistulas.105

The HiSCR was developed for the PIONEER studies105,106 to assess the response to ADA treatment. It is the only HS scoring system to undergo an extensive validation process with a meaningful clinical endpoint for HS treatment evaluation that is easy to use. Compared to the HS-PGA score (clear, minimal, mild), HiSCR was more responsive to change in patients with HS.105,106

CORRESPONDENCE

Cristina Marti-Amarista, MD, 101 Nicolls Road, Stony Brook, NY, 11794-8228; [email protected]

1. Bergler-Czop B, Hadasik K, Brzezińska-Wcisło L. Acne inversa: difficulties in diagnostics and therapy. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2015;32:296-301. doi: 10.5114/pdia.2014.44012

2. Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.067

3. Fimmel S, Zouboulis CC. Comorbidities of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa). Dermatoendocrinol. 2010;2:9-16. doi: 10.4161/derm.2.1.12490

4. Kokolakis G, Wolk K, Schneider-Burrus S, et al. Delayed diagnosis of hidradenitis suppurativa and its effect on patients and healthcare system. Dermatology. 2020;236:421-430. doi: 10.1159/000508787

5. Gulliver W, Landells IDR, Morgan D, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a novel model of care and an integrative strategy to adopt an orphan disease. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:71-77. doi: 10.1177/1203475417736290

6. Savage KT, Gonzalez Brant E, Flood KS, et al. Publication trends in hidradenitis suppurativa from 2008 to 2018. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1885-1889. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16213.

7. Narla S, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH. The most recent advances in understanding and managing hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Res. 2020;9:F1000. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.26083.1

8. Vossen ARJV, van der Zee HH, Prens EP. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review integrating inflammatory pathways into a cohesive pathogenic model. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2965. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02965

9. Frew JW, Hawkes JE, Krueger JG. A systematic review and critical evaluation of inflammatory cytokine associations in hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Res. 2018;7:1930. doi: 10.12688/f1000 research.17267.1

10. Sabat R, Jemec GBE, Matusiak Ł. Hidradenitis suppurativa. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:18. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0149-1

11. Shlyankevich J, Chen AJ, Kim GE, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa is a systemic disease with substantial comorbidity burden: a chart-verified case-control analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1144-1150. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.09.012

12. Sartorius K, Emtestam L, Jemec GB, et al. Objective scoring of hidradenitis suppurativa reflecting the role of tobacco smoking and obesity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:831-839. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09198.x

13. von Laffert M, Helmbold P, Wohlrab J, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa): early inflammatory events at terminal follicles and at interfollicular epidermis. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19:533-537. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00915.x

14. Jemec GB, Hansen U. Histology of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:994-999. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90277-7

15. Ballard K, Shuman VL. Hidradenitis suppurativa. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Updated July 15, 2022. Accessed November 28, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534867/

16. Garg A, Kirby JS, Lavian J, et al. Sex- and age-adjusted population analysis of prevalence estimates for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:760-764. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0201

17. Phan K, Charlton O, Smith SD. Global prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa and geographical variation—systematic review and meta-analysis. BioMed Dermatol. 2020;4. doi: 10.1186/s41702-019-0052-0

18. Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population-based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:97-103. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.255

19. Sachdeva M, Shah M, Alavi A. Race-specific prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:177-187. doi: 10.1177/1203475420972348

20. Vaidya T, Vangipuram R, Alikhan A. Examining the race-specific prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa at a large academic center; results from a retrospective chart review. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt9xc0n0z1. doi: 10.5070/D3236035391

21. Price KN, Hsiao JL, Shi VY. Race and ethnicity gaps in global hidradenitis suppurativa clinical trials. Dermatology. 2021;237:97-102. doi: 10.1159/000504911

22. Schrader AM, Deckers IE, van der Zee HH, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective study of 846 Dutch patients to identify factors associated with disease severity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:460-467. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.04.001

23. Frew JW, Vekic DA, Wood J, et al. A systematic review and critical evaluation of reported pathogenic sequence variants in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:987-998. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15441

24. Wolk K, Join-Lambert O, Sabat R. Aetiology and pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:999-1010. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19556

25. Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1045-1058. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090

26. Sabat R, Chanwangpong A, Schneider-Burrus S, et al. Increased prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with acne inversa. PloS One. 2012;7:e31810. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031810

27. Loh TY, Hendricks AJ, Hsiao JL, et al. Undergarment and fabric selection in the management of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2021;237:119-124. doi: 10.1159/000501611

28. Rodríguez-Zuñiga MJM, García-Perdomo HA, Ortega-Loayza AG. Association between hidradenitis suppurativa and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2019;110:279-288. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2018.10.020

29. Walker JM, Garcet S, Aleman JO, et al. Obesity and ethnicity alter gene expression in skin. Sci Rep. 2020;10:14079. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70244-2.

30. Boer J, Nazary M, Riis PT. The role of mechanical stress in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:37-43. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2015.08.011

31. Vossen ARJV, van Straalen KR, Swolfs EFH, et al. Nicotine dependency and readiness to quit smoking among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2021;237:383-385. doi: 10.1159/000514028

32. Kromann CB, Deckers IE, Esmann S, et al. Risk factors, clinical course and long-term prognosis in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:819-824. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13090

33. Clark AK, Quinonez RL, Saric S, et al. Hormonal therapies for hidradenitis suppurativa: review. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt6383k0n4. doi: 10.5070/D32310036990

34. Saric-Bosanac S, Clark AK, Sivamani RK, et al. The role of hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-like axis in inflammatory pilosebaceous disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2020;26:13030/qt8949296f. doi: 10.5070/D3262047430

35. Riis PT, Ring HC, Themstrup L, et al. The role of androgens and estrogens in hidradenitis suppurativa – a systematic review. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2016;24:239-249.

36. Hsiao JL, Antaya RJ, Berger T, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa and concomitant pyoderma gangrenosum: a case series and literature review. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1265-1270. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.328

37. Ah-Weng A, Langtry JAA, Velangi S, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:669-671. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01897.x

38. Kirthi S, Hellen R, O’Connor R, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa and Crohn’s disease: a case series. Ir Med J. 2017;110:618.

39. Dumont LM, Landman C, Sokol H, et al; CD-HS Study Group. Increased risk of permanent stoma in Crohn’s disease associated with hidradenitis suppurativa: a case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:303-310. doi: 10.1111/apt.15863

40. Marzano AV, Ceccherini I, Gattorno M, et al. Association of pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH) shares genetic and cytokine profiles with other autoinflammatory diseases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:e187. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000187.

41. Vinkel C, Thomsen SF. Hidradenitis suppurativa: causes, features, and current treatments. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:17-23.

42. Wipperman J, Bragg DA, Litzner B. Hidradenitis suppurativa: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100:562-569.

43. Theut Riis P, Pedersen OB, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:774-781. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16998.

44. Dufour DN, Emtestam L, Jemec GB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a common and burdensome, yet under-recognised, inflammatory skin disease. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:216-221; doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2013-131994

45. Vinding GR, Miller IM, Zarchi K, et al. The prevalence of inverse recurrent suppuration: a population-based study of possible hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:884-889. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12787

46. Bassas-Vila J, González Lama Y. Hidradenitis suppurativa and perianal Crohn disease: differential diagnosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107(suppl 2):27-31. doi: 10.1016/S0001-7310(17) 30006-6

47. Valour F, Sénéchal A, Dupieux C, et al. Actinomycosis: etiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, and management. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:183-197. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S39601

48. Fuchs W, Brockmeyer NH. Sexually transmitted infections. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2014;12:451-463. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12310

49. Hap W, Frejlich E, Rudno-Rudzińska J, et al. Pilonidal sinus: finding the righttrack for treatment. Pol Przegl Chir. 2017;89:68-75. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0009.6009

50. Al-Hamdi KI, Saadoon AQ. Acne onglobate of the scalp. Int J Trichology. 2020;12:35-37. doi: 10.4103/ijt.ijt_117_19

51. Balestra A, Bytyci H, Guillod C, et al. A case of ulceroglandular tularemia presenting with lymphadenopathy and an ulcer on a linear morphoea lesion surrounded by erysipelas. Int Med Case Rep J. 2018;11:313-318. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S178561

52. Ibler KS, Kromann CB. Recurrent furunculosis – challenges and management: a review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:59-64. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S35302

53. Ingram JR, Hadjieconomou S, Piguet V. Development of core outcome sets in hidradenitis suppurativa: systematic review of outcome measure instruments to inform the process. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:263-272. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14475

54. Zouboulis CC, Tzellos T, Kyrgidis A, et al; European Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation Investigator Group. Development and validation of the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System (I4), a novel dynamic scoring system to assess HS severity. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1401-1409. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15748

55. Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Resource. Hidradenitis suppurativa stages: Hurley Staging System. www.hsdiseasesource.com/hs-disease-staging. Accessed October 11, 2022.

56. Ovadja ZN, Schuit MM, van der Horst CMAM, et al. Inter- and interrater reliability of Hurley staging for hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:344-349. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17588

57. Wortsman X, Jemec GBE. Real-time compound imaging ultrasound of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1340-1342. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33286.x

58. Napolitano M, Calzavara-Pinton PG, Zanca A, et al. Comparison of clinical and ultrasound scores in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from an Italian ultrasound working group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:e84-e87. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15235

59. Bukvić Mokos Z, Miše J, Balić A, et al. Understanding the relationship between smoking and hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2020;28:9-13.

60. Shavit E, Dreiher J, Freud T, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in 3207 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:371-376. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12567

61. Kouris A, Platsidaki E, Christodoulou C, et al. Quality of life and psychosocial implications in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2016;232:687-691. doi: 10.1159/000453355

62 Ingram JR, Woo PN, Chua SL, et al. Interventions for hidradenitis suppurativa: a Cochrane systematic review incorporating GRADE assessment of evidence quality. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:970-978. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14418

63. Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American clinical management guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations: part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.068

64. Gulliver W, Zouboulis CC, Prens E, et al. Evidence-based approach to the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa, based on the European guidelines for hidradenitis suppurativa. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2016;17:343-351. doi: 10.1007/s11154-016-9328-5

65. Vena GA, Cassano N. Drug focus: adalimumab in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. Biologics. 2007;1:93-103.

66. Kimball AB, Kerdel F, Adams D, et al. Adalimumab for the treatment of moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a parallel randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:846-55. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-12-201212180-00004

67. Zouboulis CC, Okun MM, Prens EP, et al. Long-term adalimumab efficacy in patients with moderate-to-severe hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: 3-year results of a phase 3 open-label extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:60-69.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.040

68. Jemec GB, Wendelboe P. Topical clindamycin versus systemic tetracycline in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:971-974. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70272-5

69. Gener G, Canoui-Poitrine F, Revuz JE, et al. Combination therapy with clindamycin and rifampicin for hidradenitis suppurativa: a series of 116 consecutive patients. Dermatology. 2009;219:148-154. doi: 10.1159/000228334

70. Grant A, Gonzalez T, Montgomery MO, et al. Infliximab therapy for patients with moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:205-217. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.06.050

71. Blok JL, Spoo JR, Leeman FWJ, et al. Skin-tissue-sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling (STEEP): a surgical treatment option for severe hidradenitis suppurativa Hurley stage II/III. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:379-382. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12376

72. Mahmoud BH, Tierney E, Hexsel CL, et al. Prospective controlled clinical and histopathologic study of hidradenitis suppurativa treated with the long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium-aluminium-garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:637-645. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.07.048

73. Tierney E, Mahmoud BH, Hexsel C, et al. Randomized control trial for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with a neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet laser. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1188-1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01214.x

74. Hazen PG, Hazen BP. Hidradenitis suppurativa: successful treatment using carbon dioxide laser excision and marsupialization. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:208-213. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01427.x

75. van der Zee HH, Prens EP, Boer J. Deroofing: a tissue-saving surgical technique for the treatment of mild to moderate hidradenitis suppurativa lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:475-480. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.12.018

76. Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of adalimumab for hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:422-434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504370. PMID: 27518661.

77. Adams DR, Yankura JA, Fogelberg AC, et al. Treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with etanercept injection. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:501-504. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.72

78. Tursi A. Concomitant hidradenitis suppurativa and pyostomatitis vegetans in silent ulcerative colitis successfully treated with golimumab. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:1511-1512. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2016.09.010

79. Tzanetakou V, Kanni T, Giatrakou S, et al. Safety and efficacy of anakinra in severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:52-59. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.3903.

80. Romaní J, Vilarrasa E, Martorell A, et al. Ustekinumab with intravenous infusion: results in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2020;236:21-24. doi: 10.1159/000501075

81. Kane SV. Preparing for biologic or immunosuppressant therapy. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011;7:544-546.

82. Davis W, Vavilin I, Malhotra N. Biologic therapy in HIV: to screen or not to screen. Cureus. 2021;13:e15941. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15941

83. Papp KA, Haraoui B, Kumar D, et al. Vaccination guidelines for patients with immune-mediated disorders on immunosuppressive therapies. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:50-74. doi: 10.1177/1203475418811335

84. Clemmensen OJ. Topical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa with clindamycin. Int J Dermatol. 1983;22:325-328. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1983.tb02150.x

85. Hunger RE, Laffitte E, Läuchli S, et al. Swiss practice recommendations for the management of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. Dermatology. 2017;233:113-119. doi: 10.1159/000477459

86. Zouboulis CC, Bechara FG, Dickinson-Blok JL, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: a practical framework for treatment optimization - systematic review and recommendations from the HS ALLIANCE working group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:19-31. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15233

87. Riis PT, Boer J, Prens EP, et al. Intralesional triamcinolone for flares of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): a case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1151-1155. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.049

88. Fajgenbaum K, Crouse L, Dong L, et al. Intralesional triamcinolone may not be beneficial for treating acute hidradenitis suppurativa lesions: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:685-689. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002112

89. Mortimer PS, Dawber RP, Gales MA, et al. A double-blind controlled cross-over trial of cyproterone acetate in females with hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:263-268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1986.tb05740.x

90. Kraft JN, Searles GE. Hidradenitis suppurativa in 64 female patients: retrospective study comparing oral antibiotics and antiandrogen therapy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2007;11:125-131. doi: 10.2310/7750.2007.00019

91. Lee A, Fischer G. A case series of 20 women with hidradenitis suppurativa treated with spironolactone. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:192-196. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12362

92. Khandalavala BN. A disease-modifying approach for advanced hidradenitis suppurativa (regimen with metformin, liraglutide, dapsone, and finasteride): a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:70-78. doi: 10.1159/000473873

93. Verdolini R, Clayton N, Smith A, et al. Metformin for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a little help along the way. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1101-1108. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04668.x

94. Khandalavala BN, Do MV. Finasteride in hidradenitis suppurativa: a “male” therapy for a predominantly “female” disease. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2016;9:44-50.

95. Mota F, Machado S, Selores M. Hidradenitis suppurativa in children treated with finasteride-a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:578-583. doi: 10.1111/pde.13216

96. Doménech C, Matarredona J, Escribano-Stablé JC, et al. Facial hidradenitis suppurativa in a 28-year-old male responding to finasteride. Dermatology. 2012;224:307-308. doi: 10.1159/000339477

97. Patel N, McKenzie SA, Harview CL, et al. Isotretinoin in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:473-475. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2019.1670779

98. Boer J, van Gemert MJ. Long-term results of isotretinoin in the treatment of 68 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:73-76. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99) 70530-x

99. Huang CM, Kirchhof MG. A new perspective on isotretinoin treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a retrospective chart review of patient outcomes. Dermatology. 2017;233:120-125. doi: 10.1159/000477207

100. Prens LM, Huizinga J, Janse IC. Surgical outcomes and the impact of major surgery on quality of life, activity impairment and sexual health in hidradenitis suppurativa patients: a prospective single centre study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:1941-1946. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15706

101. Ritz JP, Runkel N, Haier J, et al. Extent of surgery and recurrence rate of hidradenitis suppurativa. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1998;13:164-168. doi: 10.1007/s003840050159

102. Mehdizadeh A, Hazen PG, Bechara FG, et al. Recurrence of hidradenitis suppurativa after surgical management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S70-S77. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.044.

103. Smith HS, Chao JD, Teitelbaum J. Painful hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:435-444. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181ceb80c

104. Horváth B, Janse IC, Sibbald GR. Pain management in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 suppl 1):S47-S51. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.046

105. Kimball AB, Sobell JM, Zouboulis CC, et al. HiSCR (Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response): a novel clinical endpoint to evaluate therapeutic outcomes in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa from the placebo-controlled portion of a phase 2 adalimumab study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:989-994. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13216

106. Kimball AB, Jemec GB, Yang M, et al. Assessing the validity, responsiveness and meaningfulness of the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response (HiSCR) as the clinical endpoint for hidradenitis suppurativa treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1434-1442. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13270

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), also known as acne inversa or Verneuil disease, is a chronic, recurrent, inflammatory occlusive disease affecting the terminal follicular epithelium in apocrine gland–bearing skin areas.1 HS manifests as painful nodules, abscesses, fistulas, and scarring and often has a severe psychological impact on the affected patient.2

When HS was first identified in the 1800s, it was believed to result from a dysfunction of the sweat glands.3 In 1939, scientists identified the true cause: follicular occlusion.3

Due to its chronic nature, heterogeneity in presentation, and apparent low prevalence,4 HS is considered an orphan disease.5 Over the past 10 years, there has been a surge in HS research—particularly in medical management—which has provided a better understanding of this condition.6,7

In this review, we discuss the most updated evidence regarding the diagnosis and treatment of HS to guide the family physician (FP)’s approach to managing this debilitating disease. But first, we offer a word about the etiology and pathophysiology of the condition.

3 events set the stage for hidradenitis suppurativa

Although the exact cause of HS is still unknown, some researchers have hypothesized that HS results from a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental and lifestyle factors.8-12 The primary mechanism of HS is the obstruction of the terminal follicular epithelium by a keratin plug.1,13,14 A systematic review of molecular inflammatory pathways involved in HS divides the pathogenesis of HS into 3 events: follicular occlusion followed by dilation, follicular rupture and inflammatory response, and chronic inflammatory state with sinus tracts.8

An underreported condition

HS is often underreported and misdiagnosed.4,15 Globally, the prevalence of HS varies from < 1% to 4%.15,16 A systematic review with meta-analysis showed a higher prevalence of HS in females compared to males in American and European populations.17 In the United States, the overall frequency of HS is 0.1%, or 98 per 100,000 persons.16 The prevalence of HS is highest among patients ages 30 to 39 years; there is decreased prevalence in patients ages 55 years and older.16,18

Who is at heightened risk?

Recent research has shown a relationship between ethnicity and HS.16,19,20 African American and biracial groups (defined as African American and White) have a 3-fold and 2-fold greater prevalence of HS, respectively, compared to White patients.16 However, the prevalence of HS in non-White ethnic groups may be underestimated in clinical trials due to a lack of representation and subgroup analyses based on ethnicity, which may affect generalizability in HS recommendations.21

Continue to: Genetic predisposition

Genetic predisposition. As many as 40% of patients with HS report having at least 1 affected family member. A positive family history of HS is associated with earlier onset, longer disease duration, and severe disease.22 HS is genetically heterogeneous, and several mutations (eg, gamma secretase, PSTPIP1, PSEN1 genes) have been identified in patients and in vitro as the cause of dysregulation of epidermal proliferation and differentiation, immune dysregulation, and promotion of amyloid formation.8,23-25

Obesity and metabolic risk factors. There is a strong relationship between HS and obesity. As many as 70% of patients with HS are obese, and 9% to 40% have metabolic syndrome.12,18,26-28 Obesity is associated with maceration and mechanical stress, increased fragility of the dermo-epidermal junction, changes in cutaneous blood flow, and subdermal fat inflammation—all of which favor the pathophysiology of HS.29,30

Smoking. Tobacco smoking is associated with severe HS and a lower chance of remission.12 Population-based studies have shown that as many as 90% of patients with HS have a history of smoking ≥ 20 packs of cigarettes per year.1,12,18,31,32 The nicotine and thousands of other chemicals present in cigarettes trigger keratinocytes and fibroblasts, resulting in epidermal hyperplasia, infundibular hyperkeratosis, excessive cornification, and dysbiosis.8,23,24

Hormones. The exact role sex hormones play in the pathogenesis of HS remains unclear.8,32 Most information is based primarily on small studies looking at antiandrogen treatments, HS activity during the menstrual cycle and pregnancy, HS exacerbation related to androgenic effects of hormonal contraception, and the association of HS with metabolic-endocrine disorders (eg, polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]).8,33

Androgens induce hyperkeratosis that may lead to follicular occlusion—the hallmark of HS pathology.34 A systematic review looking at the role of androgen and estrogen in HS found that while some patients with HS have elevated androgen levels, most have androgen and estrogen levels within normal range.35 Therefore, increased peripheral androgen receptor sensitivity has been hypothesized as the mechanism of action contributing to HS manifestation.34

Continue to: Host-defense defects

Host-defense defects. HS shares a similar cytokine profile with other well-established immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including pyoderma gangrenosum (PG)36,37 and Crohn disease.38-40 HS is characterized by the expression of several immune mediators, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), interleukin-1 alpha (IL-1 alpha), IL-1 beta, IL-8, IL-17, and the IL-23/T helper 17 pathway, all of which are upregulated in other inflammatory diseases and also result in an abnormal innate immune response.8,24 The recently described clinical triad of PG, acne, and HS (PASH) and the tetrad of pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne, and HS (PAPASH) further support the role of immune dysregulation in the pathogenesis of HS.40 Nonetheless, further studies are needed to determine the exact pathways of cytokine effect in HS.41

Use these criteria to make the diagnosis

The US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations (HSF) guidelines base the clinical diagnosis of HS on the following criteria2:

- Typical HS lesions: Erythematous skin lesions; inflamed, deep-seated painful nodules; “tombstone” double-ended comedones; sinus tracts; scarring; deformity. FIGURES 1A-1E show typical lesions seen in patients with HS.

- Typical locations: Intertriginous regions—apocrine gland–containing areas in axilla, groin, perineal region, buttocks, gluteal cleft, and mammary folds; beltline and waistband areas; areas of skin compression and friction.

- Recurrence and chronicity: Recurrent painful or suppurating lesions that appear more than twice in a 6-month period.2,41-43

Patients with HS usually present with painful recurrent abscesses and scarring and often report multiple visits to the emergency department for drainage or failed antibiotic treatment for abscesses.15,44

Ask patients these 2 questions. Vinding et al45 developed a survey for the diagnosis of HS using 2 simple questions based on the 3 criteria established by the HSF:

- “Have you had an outbreak of boils during the last 6 months?” and

- “Where and how many boils have you had?” (This question includes a list of the typical HS locations—eg, axilla, groin, genitals, area under breast.)

In their questionnaire, Vinding et al45 found that an affirmative answer to Question 1 and reports of > 2 boils in response to Question 2 correlated to a sensitivity of 90%, specificity of 97%, positive predictive value of 96%, and negative predictive value of 92% for the diagnosis of HS. The differential diagnosis of HS is summarized in TABLE 1.42,45-52

Continue to: These tools can help you to stage hidradenitis suppurativa

These tools can help you to stage hidradenitis suppurativa

Multiple tools are available to assess the severity of HS.53 We will describe the Hurley staging system and the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System (IHS4). Other diagnostic tools, such as the Sartorius score and the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Physician’s Global Assessment Scale (HS-PGA), can be time-consuming and challenging to interpret, limiting their use in the clinical setting.2,54

Hurley staging system (available at www.hsdiseasesource.com/hs-disease-staging) considers the presence of nodules, abscesses, sinus tracts, and scarring affecting an entire anatomical area.13,55 This system is most useful as a rapid classification tool for patients with HS in the clinical setting but should not be used to assess clinical response.2,13,56

The IHS4 (available at https://online library.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjd.15748) is a validated and easy-to-use tool for assessing HS and guiding the therapeutic strategy in clinical practice.54 With IHS4, the clinician must calculate the following:

- total number of nodules > 10 mm in diameter

- total number of abscesses multiplied by 2, and

- total number of draining tunnels (fistulae/sinuses) multiplied by 4.

Mild HS is defined as a score ≤ 3 points; moderate HS, 4 to 10 points; and severe HS, ≥ 11 points.54

No diagnostic tests, but ultrasound may be helpful

There are currently no established biological markers or specific tests for diagnosing HS.15 Ultrasound is emerging as a tool to assess dermal thickness, hair follicle morphology, and number and extent of fluid collections. Two recent studies showed that pairing clinical assessment with ultrasound findings improves accuracy of scoring in 84% of cases.57,58 For patients with severe HS, skin biopsy can be considered to rule out squamous cell carcinoma. Cultures, however, have limited utility except for suspected superimposed bacterial infection.2

Continue to: Screening for comorbidities

Screening for comorbidities

HSF recommends clinicians screen patients for comorbidities associated with HS (TABLE 2).2 Overall, screening patients for active and past history of smoking is strongly recommended, as is screening for metabolic syndrome, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes (1.5- to 3-fold greater risk of type 2 diabetes in HS patients), and PCOS (3-fold greater risk).2,26,27,59 Screening patients for depression and anxiety is also routinely recommended.2 However, the authors of this article strongly recommend screening all patients with HS for psychiatric comorbidities, as research has shown a 2-fold greater risk of depression and anxiety, social isolation, and low self-esteem that severely limits quality of life (QOL) in this patient population.60,61

Management

Treat existing lesions, reduce formation of new ones

The main goals of treatment for patients with HS are to treat existing lesions and reduce associated symptoms, reduce the formation of new lesions, and minimize associated psychological morbidity.15 FPs play an important role in the early diagnosis, treatment, and comprehensive care of patients with HS. This includes monitoring patients, managing comorbidities, making appropriate referrals to dermatologists, and coordinating the multidisciplinary care that patients with HS require.

A systematic review identified more than 50 interventions used to treat HS, most based on small observational studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with a high risk of bias.62 FIGURE 22,62-69 provides an evidence-based treatment algorithm for HS, and TABLE 32,63,64,70-75 summarizes the most commonly used treatments.

Biologic agents

Adalimumab (ADA) is a fully human immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody that binds to TNF-alpha, neutralizes its bioactivity, and induces apoptosis of TNF-expressing mononuclear cells. It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for active refractory moderate and severe HS.62,65 Several double-blinded RCTs, including PIONEER I and PIONEER II, studied the effectiveness of ADA for HS and found significant clinical responses at Week 12, 50% reduction in abscess and nodule counts, no increase in abscesses or draining fistulas at Week 12, and sustained improvement in lesion counts, pain, and QOL.66,67,76

IL-1 and IL-23 inhibitors. The efficacy of etanercept and golimumab (anti-TNF), as well as anakinra (IL-1 inhibitor) and ustekinumab (IL-1/IL-23 inhibitor), continue to be investigated with variable results; they are considered second-line treatment for active refractory moderate and severe HS after ADA.65,77-80 Infliximab (IL-1 beta inhibitor) has shown no effect on reducing disease severity.70Compared to other treatments, biologic therapy is associated with higher costs (TABLE 3),2,63,64,70-75 an increased risk for reactivation of latent infections (eg, tuberculosis, herpes simplex, and hepatitis C virus [HCV], and B [HBV]), and an attenuated response to vaccines.81 Prior to starting biologic therapy, FPs should screen patients with HS for tuberculosis and HBV, consider HIV and HCV screening in at-risk patients, and optimize the immunization status of the patient.82,83 While inactivated vaccines can be administered without discontinuing biologic treatment, patients should avoid live-attenuated vaccines while taking biologics.83

Continue to: Antibiotic therapy

Antibiotic therapy

Topical antibiotics are considered first-line treatment for mild and moderate uncomplicated HS.63,64 Clindamycin 1%, the only topical antibiotic studied in a small double-blind RCT of patients with Hurley stage I and stage II HS, demonstrated significant clinical improvement after 12 weeks of treatment (twice- daily application), compared to placebo.84 Topical clindamycin is also recommended to treat flares in patients with mild disease.2,64

Oral antibiotics. Tetracycline (500 mg twice daily for 4 months) is considered a second-line treatment for patients with mild HS.64,68 Doxycycline (200 mg/d for 3 months) may also be considered as a second-line treatment in patients with mild disease.85

Combination oral clindamycin (300 mg) and rifampicin (300 mg) twice daily for 10 weeks is recommended as first-line treatment for patients with moderate HS.2,64,69 Combination rifampin (300 mg twice daily), moxifloxacin (400 mg/d), and metronidazole (500 mg three times a day) is not routinely recommended due to increased risk of toxicity.2

Ertapenem (1 g intravenously daily for 6 weeks) is supported by lower-level evidence as a third-line rescue therapy option and as a bridge to surgery; however, limitations for home infusions, costs, and concerns for antibiotic resistance limit its use.2,86

Corticosteroids and systemic immunomodulators

Intralesional triamcinolone (2-20 mg) may be beneficial in the early stages of HS, although its use is based on a small prospective open study of 33 patients.87 A recent double-blind placebo-controlled RCT comparing varying concentrations of intralesional triamcinolone (10 mg/mL and 40 mg/mL) vs normal saline showed no statistically significant difference in inflammatory clearance, pain reduction, or patient satisfaction.88

Continue to: Short-term systemic corticosteroid tapers...

Short-term systemic corticosteroid tapers (eg, prednisone, starting at 0.5-1 mg/kg) are recommended to treat flares. Long-term corticosteroids and cyclosporine are reserved for patients with severe refractory disease; however, due to safety concerns, their regular use is strongly discouraged.63,64,85 There is limited evidence to support the use of methotrexate for severe refractory disease, and its use is not recommended.63

Hormonal therapy

The use of hormonal therapy for HS is limited by the low-quality evidence (eg, anecdotal evidence, small retrospective analyses, uncontrolled trials).33,63 The only exception is a small double-blind controlled crossover trial from 1986 showing that the antiandrogen effects of combination oral contraceptives (ethinyloestradiol 50 mcg/cyproterone acetate in a reverse sequential regimen and ethinyloestradiol 50 mcg/norgestrel 500 mcg) improved HS lesions.89

Spironolactone, an antiandrogen diuretic, has been studied in small case report series with a high risk for bias. It is used mainly in female patients with mild or moderate disease, or in combination with other agents in patients with severe HS. Further research is needed to determine its utility in the treatment of HS.63,90,91

Metformin, alone or in combination with other therapies (dapsone, finasteride, liraglutide), has been analyzed in small prospective studies of primarily female patients with different severities of HS, obesity, and PCOS. These studies have shown improvement in lesions, QOL, and reduction of workdays lost.92,93

Finasteride. Studies have shown finasteride (1.25-5 mg/d) alone or in combination with other treatments (metformin, liraglutide, levonorgestrel-ethinyl estradiol, and dapsone) provided varying degrees of resolution or improvement in patients with severe and advanced HS. Finasteride has been used for 4 to 16 weeks with a good safety profile.92,94-96

Continue to: Retinoids

Retinoids

Acitretin, alitretinoin, and isotretinoin have been studied in small retrospective studies to manage HS, with variable results.97-99 Robust prospective studies are needed. Retinoids, in general, should be considered as a second- or third-line treatment for moderate to severe HS.63

Surgical intervention

Surgical interventions, which should be considered in patients with widespread mild, moderate, or severe disease, are associated with improved daily activity and work productivity.100 Incision and drainage should be avoided in patients with HS, as this technique does not remove the affected follicles and is associated with 100% recurrence.101

Wide excision is the preferred surgical technique for patients with Hurley stage II and stage III HS; it is associated with lower recurrence rates (13%) compared to local excision (22%) and deroofing (27%).102 Secondary intention healing is the most commonly chosen method, based on lower recurrence rates than primary closure.102

STEEP and laser techniques. The skin-tissue-sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling (STEEP) procedure involves successive tangential excision of affected tissue until the epithelized bottom of the sinus tracts has been reached. This allows for the removal of fibrotic tissue and the sparing of the deep subcutaneous fat. STEEP is associated with 30% of relapses after 43 months.71

Laser surgery has also been studied in patients with Hurley stage II and stage III HS. The most commonly used lasers for HS are the 1064-nm neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd: YAG) and the carbon dioxide laser; they have been shown to reduce disease severity in inguinal, axillary, and inflammatory sites.72-74

Pain management: Start with lidocaine, NSAIDs

There are few studies about HS-associated pain management.103 For acute episodes, short-acting nonopioid local treatment with lidocaine, topical or oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and acetaminophen are preferred. Opioids should be reserved for moderate-to-severe pain that has not responded to other analgesics. Adjuvant therapy with pregabalin, gabapentin, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors can also be considered for the comanagement of pain and depression.62,104

Consider this tool to measure treatment response

The HS clinical response (HiSCR) tool is an outcome measure used to evaluate treatment outcomes. The tool uses an HS-specific binary score with the following criteria:

- ≥ 50% reduction in the number of inflammatory nodules;

- no increase in the number of abscesses; and

- no increase in the number of draining fistulas.105

The HiSCR was developed for the PIONEER studies105,106 to assess the response to ADA treatment. It is the only HS scoring system to undergo an extensive validation process with a meaningful clinical endpoint for HS treatment evaluation that is easy to use. Compared to the HS-PGA score (clear, minimal, mild), HiSCR was more responsive to change in patients with HS.105,106

CORRESPONDENCE

Cristina Marti-Amarista, MD, 101 Nicolls Road, Stony Brook, NY, 11794-8228; [email protected]

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), also known as acne inversa or Verneuil disease, is a chronic, recurrent, inflammatory occlusive disease affecting the terminal follicular epithelium in apocrine gland–bearing skin areas.1 HS manifests as painful nodules, abscesses, fistulas, and scarring and often has a severe psychological impact on the affected patient.2

When HS was first identified in the 1800s, it was believed to result from a dysfunction of the sweat glands.3 In 1939, scientists identified the true cause: follicular occlusion.3

Due to its chronic nature, heterogeneity in presentation, and apparent low prevalence,4 HS is considered an orphan disease.5 Over the past 10 years, there has been a surge in HS research—particularly in medical management—which has provided a better understanding of this condition.6,7

In this review, we discuss the most updated evidence regarding the diagnosis and treatment of HS to guide the family physician (FP)’s approach to managing this debilitating disease. But first, we offer a word about the etiology and pathophysiology of the condition.

3 events set the stage for hidradenitis suppurativa

Although the exact cause of HS is still unknown, some researchers have hypothesized that HS results from a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental and lifestyle factors.8-12 The primary mechanism of HS is the obstruction of the terminal follicular epithelium by a keratin plug.1,13,14 A systematic review of molecular inflammatory pathways involved in HS divides the pathogenesis of HS into 3 events: follicular occlusion followed by dilation, follicular rupture and inflammatory response, and chronic inflammatory state with sinus tracts.8

An underreported condition

HS is often underreported and misdiagnosed.4,15 Globally, the prevalence of HS varies from < 1% to 4%.15,16 A systematic review with meta-analysis showed a higher prevalence of HS in females compared to males in American and European populations.17 In the United States, the overall frequency of HS is 0.1%, or 98 per 100,000 persons.16 The prevalence of HS is highest among patients ages 30 to 39 years; there is decreased prevalence in patients ages 55 years and older.16,18

Who is at heightened risk?

Recent research has shown a relationship between ethnicity and HS.16,19,20 African American and biracial groups (defined as African American and White) have a 3-fold and 2-fold greater prevalence of HS, respectively, compared to White patients.16 However, the prevalence of HS in non-White ethnic groups may be underestimated in clinical trials due to a lack of representation and subgroup analyses based on ethnicity, which may affect generalizability in HS recommendations.21

Continue to: Genetic predisposition

Genetic predisposition. As many as 40% of patients with HS report having at least 1 affected family member. A positive family history of HS is associated with earlier onset, longer disease duration, and severe disease.22 HS is genetically heterogeneous, and several mutations (eg, gamma secretase, PSTPIP1, PSEN1 genes) have been identified in patients and in vitro as the cause of dysregulation of epidermal proliferation and differentiation, immune dysregulation, and promotion of amyloid formation.8,23-25

Obesity and metabolic risk factors. There is a strong relationship between HS and obesity. As many as 70% of patients with HS are obese, and 9% to 40% have metabolic syndrome.12,18,26-28 Obesity is associated with maceration and mechanical stress, increased fragility of the dermo-epidermal junction, changes in cutaneous blood flow, and subdermal fat inflammation—all of which favor the pathophysiology of HS.29,30

Smoking. Tobacco smoking is associated with severe HS and a lower chance of remission.12 Population-based studies have shown that as many as 90% of patients with HS have a history of smoking ≥ 20 packs of cigarettes per year.1,12,18,31,32 The nicotine and thousands of other chemicals present in cigarettes trigger keratinocytes and fibroblasts, resulting in epidermal hyperplasia, infundibular hyperkeratosis, excessive cornification, and dysbiosis.8,23,24

Hormones. The exact role sex hormones play in the pathogenesis of HS remains unclear.8,32 Most information is based primarily on small studies looking at antiandrogen treatments, HS activity during the menstrual cycle and pregnancy, HS exacerbation related to androgenic effects of hormonal contraception, and the association of HS with metabolic-endocrine disorders (eg, polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS]).8,33

Androgens induce hyperkeratosis that may lead to follicular occlusion—the hallmark of HS pathology.34 A systematic review looking at the role of androgen and estrogen in HS found that while some patients with HS have elevated androgen levels, most have androgen and estrogen levels within normal range.35 Therefore, increased peripheral androgen receptor sensitivity has been hypothesized as the mechanism of action contributing to HS manifestation.34

Continue to: Host-defense defects

Host-defense defects. HS shares a similar cytokine profile with other well-established immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including pyoderma gangrenosum (PG)36,37 and Crohn disease.38-40 HS is characterized by the expression of several immune mediators, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), interleukin-1 alpha (IL-1 alpha), IL-1 beta, IL-8, IL-17, and the IL-23/T helper 17 pathway, all of which are upregulated in other inflammatory diseases and also result in an abnormal innate immune response.8,24 The recently described clinical triad of PG, acne, and HS (PASH) and the tetrad of pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne, and HS (PAPASH) further support the role of immune dysregulation in the pathogenesis of HS.40 Nonetheless, further studies are needed to determine the exact pathways of cytokine effect in HS.41

Use these criteria to make the diagnosis

The US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations (HSF) guidelines base the clinical diagnosis of HS on the following criteria2:

- Typical HS lesions: Erythematous skin lesions; inflamed, deep-seated painful nodules; “tombstone” double-ended comedones; sinus tracts; scarring; deformity. FIGURES 1A-1E show typical lesions seen in patients with HS.

- Typical locations: Intertriginous regions—apocrine gland–containing areas in axilla, groin, perineal region, buttocks, gluteal cleft, and mammary folds; beltline and waistband areas; areas of skin compression and friction.

- Recurrence and chronicity: Recurrent painful or suppurating lesions that appear more than twice in a 6-month period.2,41-43

Patients with HS usually present with painful recurrent abscesses and scarring and often report multiple visits to the emergency department for drainage or failed antibiotic treatment for abscesses.15,44

Ask patients these 2 questions. Vinding et al45 developed a survey for the diagnosis of HS using 2 simple questions based on the 3 criteria established by the HSF:

- “Have you had an outbreak of boils during the last 6 months?” and

- “Where and how many boils have you had?” (This question includes a list of the typical HS locations—eg, axilla, groin, genitals, area under breast.)

In their questionnaire, Vinding et al45 found that an affirmative answer to Question 1 and reports of > 2 boils in response to Question 2 correlated to a sensitivity of 90%, specificity of 97%, positive predictive value of 96%, and negative predictive value of 92% for the diagnosis of HS. The differential diagnosis of HS is summarized in TABLE 1.42,45-52

Continue to: These tools can help you to stage hidradenitis suppurativa

These tools can help you to stage hidradenitis suppurativa

Multiple tools are available to assess the severity of HS.53 We will describe the Hurley staging system and the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System (IHS4). Other diagnostic tools, such as the Sartorius score and the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Physician’s Global Assessment Scale (HS-PGA), can be time-consuming and challenging to interpret, limiting their use in the clinical setting.2,54

Hurley staging system (available at www.hsdiseasesource.com/hs-disease-staging) considers the presence of nodules, abscesses, sinus tracts, and scarring affecting an entire anatomical area.13,55 This system is most useful as a rapid classification tool for patients with HS in the clinical setting but should not be used to assess clinical response.2,13,56

The IHS4 (available at https://online library.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjd.15748) is a validated and easy-to-use tool for assessing HS and guiding the therapeutic strategy in clinical practice.54 With IHS4, the clinician must calculate the following:

- total number of nodules > 10 mm in diameter

- total number of abscesses multiplied by 2, and

- total number of draining tunnels (fistulae/sinuses) multiplied by 4.

Mild HS is defined as a score ≤ 3 points; moderate HS, 4 to 10 points; and severe HS, ≥ 11 points.54

No diagnostic tests, but ultrasound may be helpful

There are currently no established biological markers or specific tests for diagnosing HS.15 Ultrasound is emerging as a tool to assess dermal thickness, hair follicle morphology, and number and extent of fluid collections. Two recent studies showed that pairing clinical assessment with ultrasound findings improves accuracy of scoring in 84% of cases.57,58 For patients with severe HS, skin biopsy can be considered to rule out squamous cell carcinoma. Cultures, however, have limited utility except for suspected superimposed bacterial infection.2

Continue to: Screening for comorbidities

Screening for comorbidities

HSF recommends clinicians screen patients for comorbidities associated with HS (TABLE 2).2 Overall, screening patients for active and past history of smoking is strongly recommended, as is screening for metabolic syndrome, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes (1.5- to 3-fold greater risk of type 2 diabetes in HS patients), and PCOS (3-fold greater risk).2,26,27,59 Screening patients for depression and anxiety is also routinely recommended.2 However, the authors of this article strongly recommend screening all patients with HS for psychiatric comorbidities, as research has shown a 2-fold greater risk of depression and anxiety, social isolation, and low self-esteem that severely limits quality of life (QOL) in this patient population.60,61

Management

Treat existing lesions, reduce formation of new ones

The main goals of treatment for patients with HS are to treat existing lesions and reduce associated symptoms, reduce the formation of new lesions, and minimize associated psychological morbidity.15 FPs play an important role in the early diagnosis, treatment, and comprehensive care of patients with HS. This includes monitoring patients, managing comorbidities, making appropriate referrals to dermatologists, and coordinating the multidisciplinary care that patients with HS require.

A systematic review identified more than 50 interventions used to treat HS, most based on small observational studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with a high risk of bias.62 FIGURE 22,62-69 provides an evidence-based treatment algorithm for HS, and TABLE 32,63,64,70-75 summarizes the most commonly used treatments.

Biologic agents

Adalimumab (ADA) is a fully human immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody that binds to TNF-alpha, neutralizes its bioactivity, and induces apoptosis of TNF-expressing mononuclear cells. It is the only medication approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for active refractory moderate and severe HS.62,65 Several double-blinded RCTs, including PIONEER I and PIONEER II, studied the effectiveness of ADA for HS and found significant clinical responses at Week 12, 50% reduction in abscess and nodule counts, no increase in abscesses or draining fistulas at Week 12, and sustained improvement in lesion counts, pain, and QOL.66,67,76

IL-1 and IL-23 inhibitors. The efficacy of etanercept and golimumab (anti-TNF), as well as anakinra (IL-1 inhibitor) and ustekinumab (IL-1/IL-23 inhibitor), continue to be investigated with variable results; they are considered second-line treatment for active refractory moderate and severe HS after ADA.65,77-80 Infliximab (IL-1 beta inhibitor) has shown no effect on reducing disease severity.70Compared to other treatments, biologic therapy is associated with higher costs (TABLE 3),2,63,64,70-75 an increased risk for reactivation of latent infections (eg, tuberculosis, herpes simplex, and hepatitis C virus [HCV], and B [HBV]), and an attenuated response to vaccines.81 Prior to starting biologic therapy, FPs should screen patients with HS for tuberculosis and HBV, consider HIV and HCV screening in at-risk patients, and optimize the immunization status of the patient.82,83 While inactivated vaccines can be administered without discontinuing biologic treatment, patients should avoid live-attenuated vaccines while taking biologics.83

Continue to: Antibiotic therapy

Antibiotic therapy

Topical antibiotics are considered first-line treatment for mild and moderate uncomplicated HS.63,64 Clindamycin 1%, the only topical antibiotic studied in a small double-blind RCT of patients with Hurley stage I and stage II HS, demonstrated significant clinical improvement after 12 weeks of treatment (twice- daily application), compared to placebo.84 Topical clindamycin is also recommended to treat flares in patients with mild disease.2,64

Oral antibiotics. Tetracycline (500 mg twice daily for 4 months) is considered a second-line treatment for patients with mild HS.64,68 Doxycycline (200 mg/d for 3 months) may also be considered as a second-line treatment in patients with mild disease.85

Combination oral clindamycin (300 mg) and rifampicin (300 mg) twice daily for 10 weeks is recommended as first-line treatment for patients with moderate HS.2,64,69 Combination rifampin (300 mg twice daily), moxifloxacin (400 mg/d), and metronidazole (500 mg three times a day) is not routinely recommended due to increased risk of toxicity.2

Ertapenem (1 g intravenously daily for 6 weeks) is supported by lower-level evidence as a third-line rescue therapy option and as a bridge to surgery; however, limitations for home infusions, costs, and concerns for antibiotic resistance limit its use.2,86

Corticosteroids and systemic immunomodulators

Intralesional triamcinolone (2-20 mg) may be beneficial in the early stages of HS, although its use is based on a small prospective open study of 33 patients.87 A recent double-blind placebo-controlled RCT comparing varying concentrations of intralesional triamcinolone (10 mg/mL and 40 mg/mL) vs normal saline showed no statistically significant difference in inflammatory clearance, pain reduction, or patient satisfaction.88

Continue to: Short-term systemic corticosteroid tapers...

Short-term systemic corticosteroid tapers (eg, prednisone, starting at 0.5-1 mg/kg) are recommended to treat flares. Long-term corticosteroids and cyclosporine are reserved for patients with severe refractory disease; however, due to safety concerns, their regular use is strongly discouraged.63,64,85 There is limited evidence to support the use of methotrexate for severe refractory disease, and its use is not recommended.63

Hormonal therapy

The use of hormonal therapy for HS is limited by the low-quality evidence (eg, anecdotal evidence, small retrospective analyses, uncontrolled trials).33,63 The only exception is a small double-blind controlled crossover trial from 1986 showing that the antiandrogen effects of combination oral contraceptives (ethinyloestradiol 50 mcg/cyproterone acetate in a reverse sequential regimen and ethinyloestradiol 50 mcg/norgestrel 500 mcg) improved HS lesions.89

Spironolactone, an antiandrogen diuretic, has been studied in small case report series with a high risk for bias. It is used mainly in female patients with mild or moderate disease, or in combination with other agents in patients with severe HS. Further research is needed to determine its utility in the treatment of HS.63,90,91

Metformin, alone or in combination with other therapies (dapsone, finasteride, liraglutide), has been analyzed in small prospective studies of primarily female patients with different severities of HS, obesity, and PCOS. These studies have shown improvement in lesions, QOL, and reduction of workdays lost.92,93