User login

- A symptom-based approach is the best means for diagnosing chronic constipation. Extensive diagnostic testing is seldom necessary unless alarm features are present (C).

- Encourage routine colon cancer screening tests for all patients aged 50 years or older (C).

When a patient tells you she is constipated, what does she really mean? You would think that a report so common about a complaint so universal would be immediately clear. But, in fact, there is no standard, widely accepted definition.

Researchers define constipation by diagnostic criteria (eg, Rome II).1

Recommendation grades based on the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Chronic Constipation Task Force are presented on our web site (TABLE W1),4 as are the strength of recommendations taxonomy (SORT) grades for evidence (TABLE W2).5

Methods

References were selected by searching Medline and InfoRetriever using the terms constipation or chronic constipation and socioeconomics, prevalence, impact, treatment(s), patient unmet needs, patient needs, and definition. Articles from 1994 to November 2005 were included. Searches were restricted to manuscripts written in English and to those examining constipation in adults (aged 18 and older).

The focus of this article is on the North American population. A note-worthy limitation is that, although references for prevalence and socioeconomic impact are recent, most statistics in these references are from data more than 10 years old.

Using a symptom-based evaluation

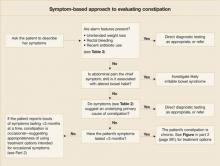

The first step in this evaluation (FIGURE) is to ask the patient to clearly describe her symptoms.

FIGURE

Symptom-based approach to evaluating constipation

Helpful aids in assessing symptoms

The Rome II criteria (TABLE 1), developed by a panel of experts, are one frame of reference in which to assess a patient’s symptoms.1

Recently, to capture a more clinically relevant definition, the American College of Gastroenterology’s Chronic Constipation Task Force described constipation as a symptom-based disorder characterized by unsatisfactory defecation—infrequent stool or difficult stool passage, including straining, incomplete evacuation, hard/lumpy stool, increased time to passing stool, use of manual maneuvers, or sense of difficulty passing stool (TABLE 1).4

TABLE 1

Definitions of chronic constipation

| ROME II DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR FUNCTIONAL CONSTIPATION |

Constipation is defined by the presence of 2 or more of the following symptoms for at least 12 weeks, which need not be consecutive, in the preceding 12 months:

|

| AMERICAN COLLEGE OF GASTROENTEROLOGY CHRONIC CONSTIPATION TASK FORCE |

| Constipation is a symptom-based disorder manifesting as unsatisfactory defecation and characterized by infrequent stool, difficult passage of stool (including straining, a sense of difficulty passing stool, prolonged time to bowel movement, or need for manual maneuvers to pass stool), or both. Chronic constipation is defined as the presence of these symptoms for at least 3 months. |

| Sources: For Rome II: Thompson et al, Gut 19991; for ACG: Brandt et al, Am J Gastroenterol 2005.4 |

Specifics to look for in history and physical

Get a thorough account of the patient’s medical and surgical history, the family’s history, and medications currently used for other conditions (TABLE 2).

Ask about medications or maneuvers the patient has tried as constipation remedies, and consider potential reasons for ineffectiveness of medications. For instance, patients often do not take enough of an agent or do not give it enough time to work.

In the physical examination, be sure to include a digital rectal exam (looking for presence of skin tags, hemorrhoids, masses, etc).

Are alarm features present? Symptoms that are red flags suggestive of organic disease include rectal bleeding, symptom onset in patients older than 50 years, family history of colorectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, and key laboratory abnormalities (eg, anemia, leukocytosis), among others (TABLE 3).4 Such symptoms of course necessitate directed evaluation of the potential underlying cause.

Clues to primary or secondary constipation. Findings from the physical examination and patient history may also help distinguish between constipation that is primary (no known cause) and that which is secondary to a physiologic disorder (eg, hemorrhoids, strictures, anal fissure), medication (eg, antidepressants, anti-spasmodics), or lifestyle habits (eg, inactivity, inadequate fiber and fluid intake) (TABLE 2).6-11

When abdominal pain is the chief symptom. If the patient reports abdominal pain, explore the possibility of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C). Symptom overlap between IBS-C and chronic constipation is common and includes hard, lumpy stools, straining, and feelings of incomplete evacuation. Abdominal pain is the main distinguishing feature.1

In the case of IBS, abdominal pain is the primary symptom and, by definition, is associated with a change in stool frequency or form. With chronic constipation, however, abdominal pain is not necessarily the primary symptom and is not always related to changes in bowel habits.1

What symptom duration tells you. Symptom duration can aid in determining whether constipation is occasional or chronic, which may influence the treatment course you recommend. In the absence of clear-cut guidelines differentiating these subcategories, the distinction is often arbitrary: constipation is considered acute/occasional if it lasts less than 3 months and chronic if it lasts 3 months or more.4

TABLE 2

Causes of secondary constipation6-11

| MAIN CAUSES | SUGGESTIVE SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS |

|---|---|

| Medical conditions | |

GI tract conditions

| Abdominal pain, nausea, cramping, vomiting, weight loss, melena, rectal bleeding, rectal pain, fever, blood in stool |

Endocrine disorders

| Reduced body hair, skin dryness, fixed edema, weight gain, urinary frequency, and urgency |

Neurologic disorders

| Focal deficits, delayed relaxation phase of the deep tendon reflex, absence of a rectoanal inhibitory reflex, cogwheel rigidity |

Systemic condition

| Numbness, pain, or color changes in fingers, toes, cheeks, nose, and ears; stiffness or pain in joints; digestive problems; sores over joints; puffy hands and feet, particularly in the morning |

Psychological disorders

| Signs of depression (eg, flat affect, poor eye contact), history of abuse |

Postsurgical complications

| Surgical scars |

Female reproduction–related issues

| Pelvic floor dyssynergia, stress incontinence |

| Medications | |

| Aluminum-containing antacids, antispasmodics, antidepressants, diuretics, anticonvulsants, pain medications (especially narcotics), and calcium-channel blockers | Prescription and over-the-counter medication use |

| Lifestyle habits | |

| Inadequate dietary fiber consumption, insufficient fluid intake, inactivity, ignoring urge to defecate | Evidence of poor dietary habits and low level of physical activity |

TABLE 3

Select alarm features suggesting dire underlying causes4,7

HISTORY

|

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

|

LABORATORY RESULTS

|

When are diagnostic tests warranted?

The choice of diagnostic tests and the timing of those tests is a judgment call in each case, ultimately based on your experience and clinical assessment. There are no universally accepted standards, but recently published evidence-based recommendations by the ACG Task Force on Chronic Constipation serve as a useful guide.

Per these recommendations, for patients with chronic constipation who do not exhibit alarm features, evidence is insufficient to recommend routine diagnostic testing (eg, colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, barium enema, serum calcium, thyroid function tests) (ACG grade: C). In the presence of alarm features, however, relevant diagnostic tests are indicated (ACG grade: C).

Routine colon cancer screening tests for all patients aged 50 years or older is recommended (ACG grade: C).

In summary, per these guidelines, the routine initial approach to patients with chronic constipation but without alarm features is empiric treatment without diagnostic testing.4

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the editorial assistance of Meera Nathan, PhD, Maribeth Bogush, PhD, and Sophia Shumyatsky, PharmD in the preparation of this manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott D. Bleser, DO, FAAFP, Bellbrook Medical Center, Inc, 4336 State Route 725, Bellbrook, OH 45305-2742. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine EJ, Muller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut 1999;45(suppl II):II43-II47.

2. Herz MJ, Kahan E, Zalevski S, Aframian R, Kuznitz D, Reichman S. Constipation: a different entity for patients and doctors. Fam Pract 1996;13:156-159.

3. Pare P, Ferrazzi S, Thompson WG, Irvine EJ, Rance L. An epidemiological survey of constipation in Canada: definitions, rates, demographics, and predictors of health care seeking. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:3130-3137.

4. Brandt LJ, Schoenfeld P, Prather CM, Quigley EMM, Schiller LR, Talley NJ. Evidenced-based position statement on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100(suppl):S1-S21.

5. Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract 2004;53:111-120.

6. Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:750-759.

7. Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1360-1368.

8. Arce DA, Ermocilla CA, Costa H. Evaluation of constipation. Am Fam Physician 2002;65:2283-2290.

9. Passmore AP. Economic aspects of pharmacotherapy for chronic constipation. Pharmacoeconomics 1995;7:14-24.

10. Jacobs TQ, Pamies RJ. Adult constipation: a review and clinical guide. J Natl Med Assoc 2001;93:22-30.

11. Petticrew M, Rodgers M, Booth A. Effectiveness of laxatives in adults. Qual Health Care 2001;10:268-273.

- A symptom-based approach is the best means for diagnosing chronic constipation. Extensive diagnostic testing is seldom necessary unless alarm features are present (C).

- Encourage routine colon cancer screening tests for all patients aged 50 years or older (C).

When a patient tells you she is constipated, what does she really mean? You would think that a report so common about a complaint so universal would be immediately clear. But, in fact, there is no standard, widely accepted definition.

Researchers define constipation by diagnostic criteria (eg, Rome II).1

Recommendation grades based on the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Chronic Constipation Task Force are presented on our web site (TABLE W1),4 as are the strength of recommendations taxonomy (SORT) grades for evidence (TABLE W2).5

Methods

References were selected by searching Medline and InfoRetriever using the terms constipation or chronic constipation and socioeconomics, prevalence, impact, treatment(s), patient unmet needs, patient needs, and definition. Articles from 1994 to November 2005 were included. Searches were restricted to manuscripts written in English and to those examining constipation in adults (aged 18 and older).

The focus of this article is on the North American population. A note-worthy limitation is that, although references for prevalence and socioeconomic impact are recent, most statistics in these references are from data more than 10 years old.

Using a symptom-based evaluation

The first step in this evaluation (FIGURE) is to ask the patient to clearly describe her symptoms.

FIGURE

Symptom-based approach to evaluating constipation

Helpful aids in assessing symptoms

The Rome II criteria (TABLE 1), developed by a panel of experts, are one frame of reference in which to assess a patient’s symptoms.1

Recently, to capture a more clinically relevant definition, the American College of Gastroenterology’s Chronic Constipation Task Force described constipation as a symptom-based disorder characterized by unsatisfactory defecation—infrequent stool or difficult stool passage, including straining, incomplete evacuation, hard/lumpy stool, increased time to passing stool, use of manual maneuvers, or sense of difficulty passing stool (TABLE 1).4

TABLE 1

Definitions of chronic constipation

| ROME II DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR FUNCTIONAL CONSTIPATION |

Constipation is defined by the presence of 2 or more of the following symptoms for at least 12 weeks, which need not be consecutive, in the preceding 12 months:

|

| AMERICAN COLLEGE OF GASTROENTEROLOGY CHRONIC CONSTIPATION TASK FORCE |

| Constipation is a symptom-based disorder manifesting as unsatisfactory defecation and characterized by infrequent stool, difficult passage of stool (including straining, a sense of difficulty passing stool, prolonged time to bowel movement, or need for manual maneuvers to pass stool), or both. Chronic constipation is defined as the presence of these symptoms for at least 3 months. |

| Sources: For Rome II: Thompson et al, Gut 19991; for ACG: Brandt et al, Am J Gastroenterol 2005.4 |

Specifics to look for in history and physical

Get a thorough account of the patient’s medical and surgical history, the family’s history, and medications currently used for other conditions (TABLE 2).

Ask about medications or maneuvers the patient has tried as constipation remedies, and consider potential reasons for ineffectiveness of medications. For instance, patients often do not take enough of an agent or do not give it enough time to work.

In the physical examination, be sure to include a digital rectal exam (looking for presence of skin tags, hemorrhoids, masses, etc).

Are alarm features present? Symptoms that are red flags suggestive of organic disease include rectal bleeding, symptom onset in patients older than 50 years, family history of colorectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, and key laboratory abnormalities (eg, anemia, leukocytosis), among others (TABLE 3).4 Such symptoms of course necessitate directed evaluation of the potential underlying cause.

Clues to primary or secondary constipation. Findings from the physical examination and patient history may also help distinguish between constipation that is primary (no known cause) and that which is secondary to a physiologic disorder (eg, hemorrhoids, strictures, anal fissure), medication (eg, antidepressants, anti-spasmodics), or lifestyle habits (eg, inactivity, inadequate fiber and fluid intake) (TABLE 2).6-11

When abdominal pain is the chief symptom. If the patient reports abdominal pain, explore the possibility of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C). Symptom overlap between IBS-C and chronic constipation is common and includes hard, lumpy stools, straining, and feelings of incomplete evacuation. Abdominal pain is the main distinguishing feature.1

In the case of IBS, abdominal pain is the primary symptom and, by definition, is associated with a change in stool frequency or form. With chronic constipation, however, abdominal pain is not necessarily the primary symptom and is not always related to changes in bowel habits.1

What symptom duration tells you. Symptom duration can aid in determining whether constipation is occasional or chronic, which may influence the treatment course you recommend. In the absence of clear-cut guidelines differentiating these subcategories, the distinction is often arbitrary: constipation is considered acute/occasional if it lasts less than 3 months and chronic if it lasts 3 months or more.4

TABLE 2

Causes of secondary constipation6-11

| MAIN CAUSES | SUGGESTIVE SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS |

|---|---|

| Medical conditions | |

GI tract conditions

| Abdominal pain, nausea, cramping, vomiting, weight loss, melena, rectal bleeding, rectal pain, fever, blood in stool |

Endocrine disorders

| Reduced body hair, skin dryness, fixed edema, weight gain, urinary frequency, and urgency |

Neurologic disorders

| Focal deficits, delayed relaxation phase of the deep tendon reflex, absence of a rectoanal inhibitory reflex, cogwheel rigidity |

Systemic condition

| Numbness, pain, or color changes in fingers, toes, cheeks, nose, and ears; stiffness or pain in joints; digestive problems; sores over joints; puffy hands and feet, particularly in the morning |

Psychological disorders

| Signs of depression (eg, flat affect, poor eye contact), history of abuse |

Postsurgical complications

| Surgical scars |

Female reproduction–related issues

| Pelvic floor dyssynergia, stress incontinence |

| Medications | |

| Aluminum-containing antacids, antispasmodics, antidepressants, diuretics, anticonvulsants, pain medications (especially narcotics), and calcium-channel blockers | Prescription and over-the-counter medication use |

| Lifestyle habits | |

| Inadequate dietary fiber consumption, insufficient fluid intake, inactivity, ignoring urge to defecate | Evidence of poor dietary habits and low level of physical activity |

TABLE 3

Select alarm features suggesting dire underlying causes4,7

HISTORY

|

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

|

LABORATORY RESULTS

|

When are diagnostic tests warranted?

The choice of diagnostic tests and the timing of those tests is a judgment call in each case, ultimately based on your experience and clinical assessment. There are no universally accepted standards, but recently published evidence-based recommendations by the ACG Task Force on Chronic Constipation serve as a useful guide.

Per these recommendations, for patients with chronic constipation who do not exhibit alarm features, evidence is insufficient to recommend routine diagnostic testing (eg, colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, barium enema, serum calcium, thyroid function tests) (ACG grade: C). In the presence of alarm features, however, relevant diagnostic tests are indicated (ACG grade: C).

Routine colon cancer screening tests for all patients aged 50 years or older is recommended (ACG grade: C).

In summary, per these guidelines, the routine initial approach to patients with chronic constipation but without alarm features is empiric treatment without diagnostic testing.4

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the editorial assistance of Meera Nathan, PhD, Maribeth Bogush, PhD, and Sophia Shumyatsky, PharmD in the preparation of this manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott D. Bleser, DO, FAAFP, Bellbrook Medical Center, Inc, 4336 State Route 725, Bellbrook, OH 45305-2742. E-mail: [email protected]

- A symptom-based approach is the best means for diagnosing chronic constipation. Extensive diagnostic testing is seldom necessary unless alarm features are present (C).

- Encourage routine colon cancer screening tests for all patients aged 50 years or older (C).

When a patient tells you she is constipated, what does she really mean? You would think that a report so common about a complaint so universal would be immediately clear. But, in fact, there is no standard, widely accepted definition.

Researchers define constipation by diagnostic criteria (eg, Rome II).1

Recommendation grades based on the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Chronic Constipation Task Force are presented on our web site (TABLE W1),4 as are the strength of recommendations taxonomy (SORT) grades for evidence (TABLE W2).5

Methods

References were selected by searching Medline and InfoRetriever using the terms constipation or chronic constipation and socioeconomics, prevalence, impact, treatment(s), patient unmet needs, patient needs, and definition. Articles from 1994 to November 2005 were included. Searches were restricted to manuscripts written in English and to those examining constipation in adults (aged 18 and older).

The focus of this article is on the North American population. A note-worthy limitation is that, although references for prevalence and socioeconomic impact are recent, most statistics in these references are from data more than 10 years old.

Using a symptom-based evaluation

The first step in this evaluation (FIGURE) is to ask the patient to clearly describe her symptoms.

FIGURE

Symptom-based approach to evaluating constipation

Helpful aids in assessing symptoms

The Rome II criteria (TABLE 1), developed by a panel of experts, are one frame of reference in which to assess a patient’s symptoms.1

Recently, to capture a more clinically relevant definition, the American College of Gastroenterology’s Chronic Constipation Task Force described constipation as a symptom-based disorder characterized by unsatisfactory defecation—infrequent stool or difficult stool passage, including straining, incomplete evacuation, hard/lumpy stool, increased time to passing stool, use of manual maneuvers, or sense of difficulty passing stool (TABLE 1).4

TABLE 1

Definitions of chronic constipation

| ROME II DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR FUNCTIONAL CONSTIPATION |

Constipation is defined by the presence of 2 or more of the following symptoms for at least 12 weeks, which need not be consecutive, in the preceding 12 months:

|

| AMERICAN COLLEGE OF GASTROENTEROLOGY CHRONIC CONSTIPATION TASK FORCE |

| Constipation is a symptom-based disorder manifesting as unsatisfactory defecation and characterized by infrequent stool, difficult passage of stool (including straining, a sense of difficulty passing stool, prolonged time to bowel movement, or need for manual maneuvers to pass stool), or both. Chronic constipation is defined as the presence of these symptoms for at least 3 months. |

| Sources: For Rome II: Thompson et al, Gut 19991; for ACG: Brandt et al, Am J Gastroenterol 2005.4 |

Specifics to look for in history and physical

Get a thorough account of the patient’s medical and surgical history, the family’s history, and medications currently used for other conditions (TABLE 2).

Ask about medications or maneuvers the patient has tried as constipation remedies, and consider potential reasons for ineffectiveness of medications. For instance, patients often do not take enough of an agent or do not give it enough time to work.

In the physical examination, be sure to include a digital rectal exam (looking for presence of skin tags, hemorrhoids, masses, etc).

Are alarm features present? Symptoms that are red flags suggestive of organic disease include rectal bleeding, symptom onset in patients older than 50 years, family history of colorectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, and key laboratory abnormalities (eg, anemia, leukocytosis), among others (TABLE 3).4 Such symptoms of course necessitate directed evaluation of the potential underlying cause.

Clues to primary or secondary constipation. Findings from the physical examination and patient history may also help distinguish between constipation that is primary (no known cause) and that which is secondary to a physiologic disorder (eg, hemorrhoids, strictures, anal fissure), medication (eg, antidepressants, anti-spasmodics), or lifestyle habits (eg, inactivity, inadequate fiber and fluid intake) (TABLE 2).6-11

When abdominal pain is the chief symptom. If the patient reports abdominal pain, explore the possibility of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C). Symptom overlap between IBS-C and chronic constipation is common and includes hard, lumpy stools, straining, and feelings of incomplete evacuation. Abdominal pain is the main distinguishing feature.1

In the case of IBS, abdominal pain is the primary symptom and, by definition, is associated with a change in stool frequency or form. With chronic constipation, however, abdominal pain is not necessarily the primary symptom and is not always related to changes in bowel habits.1

What symptom duration tells you. Symptom duration can aid in determining whether constipation is occasional or chronic, which may influence the treatment course you recommend. In the absence of clear-cut guidelines differentiating these subcategories, the distinction is often arbitrary: constipation is considered acute/occasional if it lasts less than 3 months and chronic if it lasts 3 months or more.4

TABLE 2

Causes of secondary constipation6-11

| MAIN CAUSES | SUGGESTIVE SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS |

|---|---|

| Medical conditions | |

GI tract conditions

| Abdominal pain, nausea, cramping, vomiting, weight loss, melena, rectal bleeding, rectal pain, fever, blood in stool |

Endocrine disorders

| Reduced body hair, skin dryness, fixed edema, weight gain, urinary frequency, and urgency |

Neurologic disorders

| Focal deficits, delayed relaxation phase of the deep tendon reflex, absence of a rectoanal inhibitory reflex, cogwheel rigidity |

Systemic condition

| Numbness, pain, or color changes in fingers, toes, cheeks, nose, and ears; stiffness or pain in joints; digestive problems; sores over joints; puffy hands and feet, particularly in the morning |

Psychological disorders

| Signs of depression (eg, flat affect, poor eye contact), history of abuse |

Postsurgical complications

| Surgical scars |

Female reproduction–related issues

| Pelvic floor dyssynergia, stress incontinence |

| Medications | |

| Aluminum-containing antacids, antispasmodics, antidepressants, diuretics, anticonvulsants, pain medications (especially narcotics), and calcium-channel blockers | Prescription and over-the-counter medication use |

| Lifestyle habits | |

| Inadequate dietary fiber consumption, insufficient fluid intake, inactivity, ignoring urge to defecate | Evidence of poor dietary habits and low level of physical activity |

TABLE 3

Select alarm features suggesting dire underlying causes4,7

HISTORY

|

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

|

LABORATORY RESULTS

|

When are diagnostic tests warranted?

The choice of diagnostic tests and the timing of those tests is a judgment call in each case, ultimately based on your experience and clinical assessment. There are no universally accepted standards, but recently published evidence-based recommendations by the ACG Task Force on Chronic Constipation serve as a useful guide.

Per these recommendations, for patients with chronic constipation who do not exhibit alarm features, evidence is insufficient to recommend routine diagnostic testing (eg, colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, barium enema, serum calcium, thyroid function tests) (ACG grade: C). In the presence of alarm features, however, relevant diagnostic tests are indicated (ACG grade: C).

Routine colon cancer screening tests for all patients aged 50 years or older is recommended (ACG grade: C).

In summary, per these guidelines, the routine initial approach to patients with chronic constipation but without alarm features is empiric treatment without diagnostic testing.4

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the editorial assistance of Meera Nathan, PhD, Maribeth Bogush, PhD, and Sophia Shumyatsky, PharmD in the preparation of this manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott D. Bleser, DO, FAAFP, Bellbrook Medical Center, Inc, 4336 State Route 725, Bellbrook, OH 45305-2742. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine EJ, Muller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut 1999;45(suppl II):II43-II47.

2. Herz MJ, Kahan E, Zalevski S, Aframian R, Kuznitz D, Reichman S. Constipation: a different entity for patients and doctors. Fam Pract 1996;13:156-159.

3. Pare P, Ferrazzi S, Thompson WG, Irvine EJ, Rance L. An epidemiological survey of constipation in Canada: definitions, rates, demographics, and predictors of health care seeking. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:3130-3137.

4. Brandt LJ, Schoenfeld P, Prather CM, Quigley EMM, Schiller LR, Talley NJ. Evidenced-based position statement on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100(suppl):S1-S21.

5. Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract 2004;53:111-120.

6. Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:750-759.

7. Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1360-1368.

8. Arce DA, Ermocilla CA, Costa H. Evaluation of constipation. Am Fam Physician 2002;65:2283-2290.

9. Passmore AP. Economic aspects of pharmacotherapy for chronic constipation. Pharmacoeconomics 1995;7:14-24.

10. Jacobs TQ, Pamies RJ. Adult constipation: a review and clinical guide. J Natl Med Assoc 2001;93:22-30.

11. Petticrew M, Rodgers M, Booth A. Effectiveness of laxatives in adults. Qual Health Care 2001;10:268-273.

1. Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, Heaton KW, Irvine EJ, Muller-Lissner SA. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut 1999;45(suppl II):II43-II47.

2. Herz MJ, Kahan E, Zalevski S, Aframian R, Kuznitz D, Reichman S. Constipation: a different entity for patients and doctors. Fam Pract 1996;13:156-159.

3. Pare P, Ferrazzi S, Thompson WG, Irvine EJ, Rance L. An epidemiological survey of constipation in Canada: definitions, rates, demographics, and predictors of health care seeking. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:3130-3137.

4. Brandt LJ, Schoenfeld P, Prather CM, Quigley EMM, Schiller LR, Talley NJ. Evidenced-based position statement on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100(suppl):S1-S21.

5. Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Fam Pract 2004;53:111-120.

6. Higgins PD, Johanson JF. Epidemiology of constipation in North America: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:750-759.

7. Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1360-1368.

8. Arce DA, Ermocilla CA, Costa H. Evaluation of constipation. Am Fam Physician 2002;65:2283-2290.

9. Passmore AP. Economic aspects of pharmacotherapy for chronic constipation. Pharmacoeconomics 1995;7:14-24.

10. Jacobs TQ, Pamies RJ. Adult constipation: a review and clinical guide. J Natl Med Assoc 2001;93:22-30.

11. Petticrew M, Rodgers M, Booth A. Effectiveness of laxatives in adults. Qual Health Care 2001;10:268-273.