User login

Chronic constipation: Let symptom type and severity direct treatment

- Increased fiber intake through diet (C) or fiber supplements (B) is an appropriate initial therapy for chronic constipation.

- Osmotic and stimulant laxatives may be administered to patients who do not respond to more conservative measures if the limitations of these agents are explained (B).

- Tegaserod, a selective 5-hydroxytryptamine type 4 (5-HT4) receptor partial agonist, is more effective than placebo at relieving symptoms of chronic idiopathic constipation in patients younger than 65 years of age (A).

- Patients with suspected defecation disorders and those with treatment-refractory symptoms should be referred to a gastroenterologist for further evaluation (C).

By the time a patient sees you with a complaint of constipation, chances are she has tried a remedy or 2 and is now looking for something new. However, the abandoned remedies may yet prove useful, depending on the nature of her complaint and on her understanding of how the remedy was supposed to have worked. In this article, we discuss the benefits and limitations of several treatment options in managing a patient’s distinct condition, as assessed in part 1 (page 580).

Symptom-focused treatment

As per the ACG Task Force guidelines, initial treatment of chronic constipation (in the absence of alarm features and secondary causes) is empiric.1 The patient’s symptoms—specifically those most bother-some—should direct your decisions. A plan so guided will also help you manage the patient’s expectations.

Address patients’ prior disappointments

Most patients will have self-treated before coming to see you, and some even will have tried prescribed regimens. Initial treatment of constipation has traditionally involved lifestyle changes (eg, diet, fluid, exercise modification), increased fiber intake, and laxatives. However, evidence supporting use of these modalities in this setting is sparse, and patient surveys often show dissatisfaction with these approaches. For instance, a web-based survey showed that 96% of patients with chronic constipation have tried some form of traditional medication (eg, bulking agents, stool softeners, laxatives).2 Overall, 47% were not satisfied with their current treatment, primarily because of inadequate symptom relief and unwanted side effects.

Furthermore, patient compliance with some therapies is poor because of side effects such as flatulence, distension, and bloating. Two recently published systematic reviews evaluating treatment options for patients with chronic constipation came to similar conclusions.1,3

Below we discuss the ACG Chronic Constipation Task Force conclusions and recommendations.1 Explicit communication with patients about what they can expect will help ensure treatment success.

Prescribe fiber, increase water intake

Just a few clinical trials have evaluated the effects of lifestyle changes on constipation symptoms, and they have generally been poorly designed or involved small numbers of patients (TABLE).4-7

Educating patients about proper nutrition and designating a time for daily defecation are common initial approaches, but efficacy of these strategies in this patient population has not been established (SOR: C).4,5

Exercise has dubious value. Exercise is often recommended as a way to treat constipation because of its purported effect on reducing gastrointestinal (GI) transit time (SOR: C).6 However, uncontrolled studies have found that aerobic exercise does not necessarily decrease transit time and may actually prolong it.6

Increasing water alone generally unhelpful… Few data support the benefits of increased fluid consumption, except for dehydrated patients. In one study, increased intake (to 1 L/d) of water or isotonic fluid had no effect on the stool weight of healthy volunteers.4

…but fiber plus water works. However, in a study involving patients with chronic constipation, a high-fiber diet and 2 L/d of water increased frequency of bowel movements and reduced use of laxatives compared with the same diet and ad libitum fluid intake (P<.001). By binding water, fiber increases stool weight, softens stool, decreases colonic transit time, and increases GI motility.4,5,8,9

You can recommend that patients gradually increase fiber intake over several weeks to a total of 20 g/d to 25 g/d)18 through fiber-rich foods (vegetables [eg, carrots, broccoli, string beans], fruits [eg, peaches, apples, oranges], whole-grain breads, pasta, cereal, etc) (SOR: C) or bulk supplements (eg, psyllium, methylcellulose, and polycarbophil) (SOR: B). In conjunction with other lifestyle modifications, this is a reasonable management decision.11 Because failure to balance the ratio between fiber and fluid can worsen constipation, and even cause intestinal obstruction, tell patients who increase their fiber consumption to also increase their fluid intake (30 mL/kg body weight daily).5,12

Caveats. Few data support the benefits of this approach. Epidemiologic studies show a low prevalence of constipation in countries in which fiber-rich diets are the norm,8 but extrapolating data from healthy populations to constipated patients may not be justified.13 In fact, few data from controlled trials support the use of fiber therapy in patients with constipation. In the uncontrolled Nurses’ Health Study, subjects in the highest quintile of dietary fiber intake (median intake, 20 g/d) were less likely to have constipation than those in the lowest quintile (median intake, 7 g/d).14 This general dearth of evidence led the ACG Chronic Constipation Task Force to conclude that psyllium increases stool frequency in patients with chronic constipation (ACG grade: B) but that there are insufficient data to make a recommendation about the efficacy of calcium polycarbophil, methylcellulose, and bran in this patient population (ACG grade: B).1

Important points for patients. Counsel patients for whom you recommend fiber intake that it may take several weeks for them to experience relief,5,8 and that long-term fiber use may cause abdominal distension, bloating, and flatulence.4,5,8,15 Few serious adverse effects (eg, delayed gastric emptying, anorexia, and iron and calcium malabsorption) are associated with bulking agents; however, fecal impaction may occur in patients with severe colonic inertia.16

Hypersensitivity reactions have been reported in patients who ingest psyllium and in healthcare workers exposed to it.16

Osmotic laxatives may help

When increased fiber intake fails to alleviate symptoms of constipation, patients are often prescribed an osmotic laxative (eg, magnesium hydroxide, magnesium citrate, sodium phosphate, or polyethylene glycol [PEG]) (SOR: B), which promotes water secretion in the intestines.4,8,15 However, several days may pass before the laxatives take effect, and they are indicated only for short-term use in patients with occasional constipation.1

Common adverse effects include abdominal cramping, bloating, and flatulence.4,10,17 More serious adverse effects include hypermagnesemia, hyperphosphatemia, hypercalcemia, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypovolemia, and diarrhea1,16 ; the incidences of these events were not reported.

The ACG Task Force gave PEG and lactulose grade A recommendations, based on the quality of evidence supporting their effectiveness at improving stool frequency and stool consistency in patients with chronic constipation.1 PEG was the only laxative shown in clinical trials to improve bowel movement frequency, stool consistency, and colonic transit time. However, this conclusion was based on analysis of all formulations—PMF-100, PEG 3350, PEG/electrolyte solutions, and high-molecular-weight PEG (PEG 4000); PEG 3350 (Miralax), the only PEG formulation approved by the FDA for use in patients with constipation, is indicated specifically for patients with occasional constipation. The Task Force determined that data were insufficient to make a recommendation for milk of magnesia (ACG grade: B).1

Stimulant laxatives, if all else fails

Stimulants (eg, bisacodyl, cascara, senna, ricinoleic acid) cause rhythmic muscle contractions in the intestines and increase intestinal motility and secretions.4,5,9,15,17 Controlled study data for stimulant laxatives are sparse (SOR: B).18 They work within hours,12,15,17,19 but use them judiciously.9

A common adverse effect is abdominal pain; more serious adverse effects include electrolyte imbalances, allergic reactions, and hepatotoxicity.1,16,20 However, these effects appear to be no more severe or frequent than effects of other constipation treatments. Long-term use can also cause benign pigmentation changes in the colon (Pseudomelanosis coli) and can lead to reduced colonic motility (colonic inertia).12,16

Given safety concerns with long-term use, reserve stimulant laxatives for patients who are refractory to or who cannot tolerate other agents.5,17 You should use them only as needed and for a brief time12 (the general guideline for most over-the-counter products is 1 week or less). The ACG Task Force concluded that data are insufficient to make recommendations for stimulant laxatives (ACG grade: B).1

Fiber or laxatives better?

A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials found that fiber and laxatives increased bowel movement frequency by an overall weighted mean of 1.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.1–1.8) bowel movements per week.21 However, evidence was insufficient to establish whether fiber was superior to laxatives or whether one laxative class was superior to another.

Another meta-analysis found that, in studies lasting 4 weeks or less, fiber supplements and laxatives improved stool frequency (mean increase, 1.9 stool/week) and stool weight (mean increase, 476 g) but that these benefits were not clearly distinguishable from those of placebo (stool frequency, 1 stool; stool weight, 434 g).18

Large, well-designed, comparative trials of treatments for chronic constipation in adults are needed.22 Current literature contains few thoroughly reported studies of fiber and laxative use.18 Additionally, standardized measures to assess the adverse effects and outcomes (effects on quality of life) of specific agents have rarely been incorporated.18,22 Given the problematic safety/tolerability profiles of some laxatives, it is unknown whether they improve quality of life of patients with constipation.18

TABLE

Treatments for chronic constipation

| TREATMENT | EFFICACY | SOR | OUTCOMES MEASURED | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle changes (Increased fluids, designated time for defecation, patient education)4,5,7 | High-fiber diet+2 L/d of water significantly increased bowel movement frequency and decreased laxative use (P<.001) compared with high-fiber diet alone (NNT=NA) | C | Stool weight BM frequency Laxative use | Not evaluated in controlled studies in which numbers of responders were reported |

| Exercise 4,6 | Crossover study of low-intensity physical activity minimally improved symptoms in 5 of 8 patients (NNT=1.6) | C | BM frequency, consistency Straining | Uncontrolled studies show inconsistent effects on stool weight and transit time |

| Increased dietary fiber 4,14 | In uncontrolled Nurses’ Health Study, women with high fiber intake were less likely than those with low intake to report constipation (NNT=NA) | C | BM frequency | Not evaluated in well-designed, controlled studies |

| Bulk fiber laxatives (Psyllium, methylcellulose, polycarbophil, ispaghula, bran, among others)13,18,36-38 | Improve overall bowel function at 4 weeks (NNT=7.5) | B | Bowel function at 4 weeks | Few controlled studies; efficacy results often reported only as mean scores, not as number (or %) of responders Adverse effects included abdominal pain, bloating, and flatulence |

| Osmotic laxatives (Magnesium hydroxide, magnesium citrate, sodium phosphate, polyethylene glycol, among others)4,8,15,30,39-42 | Compared with placebo, greater overall effectiveness, more effective in increasing bowel movement frequency, improving subjective well-being, and promoting complete remission of constipation (NNT=1.3–2.4) | B | Overall effectiveness BM frequency Subjective well-being related to defecation Complete remission of constipation | Few controlled studies; small populations in many studies; efficacy results often reported only as mean scores, not as number (or %) of responders |

| Adverse effects included nausea, abdominal pain or discomfort, bloating, distension, and flatulence | ||||

| Stimulant laxatives (Bisacodyl, cascara, senna, ricinoleic acid, ocusates, among others)4,15,22 | Improve bowel movement frequency (NNT=4–14.3) | B | Bowel movement frequency | Few controlled studies |

| Adverse effects include abdominal cramping, fluid and electrolyte depletion, diarrhea, allergic reactions | ||||

| 5-HT4 receptor agonists (Tegaserod)25-27 | More effective than placebo at relieving symptoms of chronic constipation (NNT=5.5–11.1) | A | Responder rate for CSBMs during first 4 weeks of treatment | Brief episodes of diarrhea, usually mild to moderate, may occur near the start of treatment; Safe for long-term use |

| NA, not applicable; NNT, number needed to treat; SOR, strength of recommendation; CSBM, complete spontaneous bowel movement. | ||||

Novel therapies

Tegaserod

Tegaserod (Zelnorm) is FDA-approved for treatment of women with IBS whose primary bowel symptom is constipation, and for treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation in women and men aged <65.23 The ACG Task Force determined that tegaserod increases the frequency of complete spontaneous bowel movements (CSBM), decreases straining, and improves stool consistency in patients with chronic constipation (ACG grade: A).1 Tegaserod binds with high affinity at human 5-HT4 receptors and augments peristalsis, increases colonic motility along the entire GI tract, and promotes intestinal secretions.23,24 (For more information on tegaserod’s mode of activity, see www.jfponline.com.)

Adverse effects. The most noteworthy adverse effect of tegaserod was diarrhea, occurring as brief episodes that were generally mild (not requiring antidiarrheal drugs), transient (occurring early after initiation of treatment and resolving after a couple of days), and self-limiting.25,26 Results of a single-blind, uncontrolled extension study in which 842 patients were administered tegaserod 2 mg or 6 mg for up to 13 months (total exposure was up to 16 months) were similar to those of shorter term studies, indicating that long-term treatment is safe and well-tolerated.27

Important advice for patients. Although tegaserod is generally well tolerated, counsel patients regarding its potential risk. Ischemic colitis, a vascular disorder that results from reduced blood flow in the colon, appears as a precaution in the current package insert.23 No cases of this condition were reported during clinical trials. Although reports of transient ischemic colitis were reported during postmarketing surveillance, they were not associated with long-term consequences, and they occurred at the expected rate in the general population and lower than the rate observed in IBS patients.23,28 To date, no vascular mechanism has been found that links colonic ischemia with tegaserod use.29 Nevertheless, patients for whom tegaserod is prescribed should be counseled to promptly report any symptoms consistent with this condition, including worsening abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, or bloody diarrhea.23

Lubiprostone

Lubiprostone (Amitiza) is a chloride channel activator that increases secretion of intestinal fluid. This agent significantly increases stool frequency, improves stool form, and decreases straining,30-32 and was recently FDA-approved for the treatment of patients with chronic idiopathic constipation.33 To date, data from lubiprostone clinical trials have not been published in full. As more data become available, it will be interesting to evaluate where this agent fits into the growing treatment armamentarium for chronic constipation.

Drugs in the pipeline

Several additional pharmacologic classes with unique modes of action are under investigation for the treatment of chronic constipation, including opioid antagonists and neurotrophic factors.34

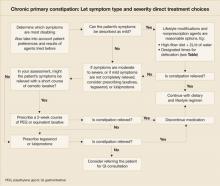

When to use which agent

In the absence of specific guidelines dictating an order of treatment options for patients with chronic constipation, base your decision on such factors as the degree to which symptoms affect a patient’s daily life, results achieved with agents in the past, patient preference, and your clinical judgment and experience ( FIGURE ). Lifestyle modifications and traditional (primarily over-the-counter) therapies are typically the initial approaches for patients with milder symptoms. Patients experiencing moderate to severe constipation-associated symptoms, those who have experienced adverse effects, and those who have not achieved satisfactory relief of constipation should be evaluated for other treatment options, including prescription laxatives, tegaserod, and lubiprostone.

Because of the heterogeneity of this disorder, successful management is patient specific. Positive outcomes may include increased stool frequency, less straining, sense of complete evacuation, resolution of abdominal bloating, and passage of soft, formed stool. Optimally, these positive symptom outcomes will translate into better overall quality of life and the ability to return to normal work and personal activities. Importantly, education and continual open dialogue with the patient are crucial to managing expectations, both for the physician and for the patient.

FIGURE

Chronic primary constipation: Let symptom type and severity direct treatment choices

When referral is indicated

Though most patients with chronic constipation can be treated successfully in the primary care setting,35 a few may require referral to a gastroenterologist. Reasons may include the following:

- Suspicion of defecatory disorders (eg, pelvic floor dyssynergia)

- Lack of sufficient response to empiric treatment

- Worsening symptoms despite treatment

- Development of GI-associated alarm features requiring diagnostic procedures that may not be feasible to conduct in the primary care clinic setting (eg, balloon distension, anorectal manometry, defecography, colonic transit, barium enema, and colonoscopy).8

Ongoing communication with the consulting gastroenterologist is critical to maintaining optimal patient care. Use a referral form to clearly explain whether the patient is being referred for a procedure (eg, specific diagnostic test) or for a consultation (eg, temporary release of the patient to the gastroenterologist to further evaluate potential causes of symptoms); this will increase the likelihood that every-one’s expectations are satisfactorily met.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the editorial assistance of Meera Nathan, PhD, Maribeth Bogush, PhD, and Sophia Shumyatsky, PharmD in the preparation of this manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott D. Bleser, DO, FAAFP, Bellbrook Medical Center, Inc, 4336 State Route 725, Bellbrook, OH 45305-2742. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Brandt LJ, Schoenfeld P, Prather CM, Quigley EMM, Schiller LR, Talley NJ. Evidenced-based position statement on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100(suppl):S1-S21.

2. Schiller LR, Dennis E, Toth G. An internet-based survey of the prevalence and symptom spectrum of chronic constipation [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:S234.-

3. Ramkumar D, Rao SSC. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:936-971.

4. Pampati V, Fogel R. Treatment options for primary constipation. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2004;7:225-233.

5. Wald A. Constipation. Med Clin North Am 2000;84:1231-1246.

6. Meshkinpour H, Selod S, Movahedi H, et al. Effects of regular exercise in management of chronic idiopathic constipation. Dig Dis Sci 1998;43:2379-2383.

7. Anti M, Pignataro G, Armuzzi A, et al. Water supplementation enhances the effect of high-fiber diet on stool frequency and laxative consumption in adult patients with functional constipation. Hepatogastroenterology 1998;45:727-732.

8. Locke GR, III, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. AGA technical review on constipation. Gastroenterol 2000;119:1766-1778.

9. Borum ML. Constipation: evaluation and management. Primary Care 2001;28:577-590.

10. Talley NJ. Management of chronic constipation. Rev Gastroenterol Disord 2004;4:18-24.

11. Locke GR, III, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. AGA Medical Position Statement: guidelines on constipation. Gastroenterol 2000;119:1761-1766.

12. Doughty DB. When fiber is not enough: current thinking on constipation management. Ostomy Wound Manage 2002;48:30-41.

13. Cheskin LJ, Kamal N, Crowell MD, Schuster MM, Whitehead WE. Mechanisms of constipation in older persons and effects of fiber compared with placebo. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:666-669.

14. Dukas L, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL. Association between physical activity, fiber intake, and other lifestyle variables and constipation in a study of women. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:1790-1796.

15. Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1360-1368.

16. Xing JH, Soffer EE. Adverse effects of laxatives. Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44:1201-1209.

17. Schiller LR. Review article: the therapy of constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:749-763.

18. Jones MP, Talley NJ, Nuyts G, Dubois D. Lack of objective evidence of efficacy of laxatives in chronic constipation. Dig Dis Sci 2002;47:2222-2230.

19. DiPalma JA. Current treatment options for chronic constipation. Rev Gastroenterol Disord 2004;(suppl 2):S34-S42.

20. Gattuso JM, Kamm MA. Adverse effects of drugs used in the management of constipation and diarrhoea. Drug Saf 1994;10:47-65.

21. Tramonte SM, Brand MB, Mulrow CD, Amato MG, O’Keefe ME, Ramirez G. The treatment of chronic constipation in adults. A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 1997;12:15-24.

22. Petticrew M, Rodgers M, Booth A. Effectiveness of laxatives in adults. Qual Health Care 2001;10:268-273.

23. Zelnorm (tegaserod maleate) tablets [prescribing information]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis; August 2004.

24. Appel-Dingemanse S. Clinical pharmacokinetics of tegaserod, a serotonin 5-HT4 receptor partial agonist with promotile activity. Clin Pharmacokinet 2002;41:1021-1042.

25. Johanson JF, Wald A, Tougas G, et al. Effect of tegaserod in chronic constipation: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:796-805.

26. Kamm MA, Muller-Lissner S, Talley NJ, et al. Tegaserod for the treatment of chronic constipation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multinational study. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:362-372.

27. Mueller-Lissner S, Kamm M, Haeck P, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of tegaserod in chronic constipation (CC) [abstract]. Gastroenterol 2004;126(Suppl 2).-

28. Schoenfeld P. Review article: the safety profile of tegaserod. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20(suppl 7):25-30.

29. Joelsson BE, Shetzline MA, Cunningham S. Ischemic colitis associated with use of tegaserod [reply]. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1363-1364.

30. Johanson JF, Gargano MA, Holland PC, Patchen ML, Ueno R. Phase III, randomized withdrawal study of RU-0211, a novel chloride channel activator for the treatment of constipation [abstract]. Gastroenterol 2004;126(suppl 2):A100.-

31. Johanson JF, Gargano MA, Holland PC, Patchen ML, Ueno R. Phase III efficacy and safety of RU-0211, a novel chloride channel activator, for the treatment of constipation [abstract]. Gastroenterol 2003;124:A104.-

32. Johanson JF, Gargano MA, Patchen ML, Ueno R. Efficacy and safety of a novel compound, RU-0211, for the treatment of constipation [abstract]. Gastroenterol 2002;122:A-315.

33. Amitiza (lubiprostone) soft gelatin capsules [prescribing information]. Bethesda, Md: Sucampo Pharmaceuticals; 2006.

34. Schiller LR. New and emerging treatment options for chronic constipation. Rev Gastroenterol Dis 2004;4:S43-S51.

35. Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Physician visits in the United States for constipation: 1958 to 1986. Dig Dis Sci 1989;34:606-611.

36. Dettmar PW, Sykes J. A multi-centre, general practice comparison of ispaghula husk with lactulose and other laxatives in the treatment of simple constipation. Curr Med Res Opin. 1998;14:227-233.

37. Badiali D, Corazziari E, Habib FI, et al. Effect of wheat bran in treatment of chronic nonorganic constipation: a double-blind controlled trial. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:349-356.

38. McRorie JW, Daggy BP, Morel JG, Diersing PS, Miner PB, Robinson M. Psyllium is superior to docusate sodium for treatment of chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998;12:491-497.

39. Klauser AG, Muhldorfer BE, Voderholzer WA, Wenzel G, Muller-Lissner SA. Polyethylene glycol 4000 for slow transit constipation. Z Gastroenterol 1995;33:5-8.

40. Cleveland MV, Flavin DP, Ruben RA, Epstein RM, Clark GE. New polyethylene glycol laxative for treatment of constipation in adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. South Med J 2001;94:478-481.

41. Corazziari E, Badiali D, Bazzocchi G, et al. Long-term efficacy, safety, and tolerability of low daily doses of isosmotic polyethylene glycol electrolyte balanced solution (PMF-100) in the treatment of functional chronic constipation. Gut 2000;46:522-526.

42. Corazziari E, Badiali D, Habib FI, et al. Small volume isosmotic polyethylene glycol electrolyte balanced solution (PMF-100) in treatment of chronic nonorganic constipation. Dig Dis Sci 1996;41:1636-1642.

- Increased fiber intake through diet (C) or fiber supplements (B) is an appropriate initial therapy for chronic constipation.

- Osmotic and stimulant laxatives may be administered to patients who do not respond to more conservative measures if the limitations of these agents are explained (B).

- Tegaserod, a selective 5-hydroxytryptamine type 4 (5-HT4) receptor partial agonist, is more effective than placebo at relieving symptoms of chronic idiopathic constipation in patients younger than 65 years of age (A).

- Patients with suspected defecation disorders and those with treatment-refractory symptoms should be referred to a gastroenterologist for further evaluation (C).

By the time a patient sees you with a complaint of constipation, chances are she has tried a remedy or 2 and is now looking for something new. However, the abandoned remedies may yet prove useful, depending on the nature of her complaint and on her understanding of how the remedy was supposed to have worked. In this article, we discuss the benefits and limitations of several treatment options in managing a patient’s distinct condition, as assessed in part 1 (page 580).

Symptom-focused treatment

As per the ACG Task Force guidelines, initial treatment of chronic constipation (in the absence of alarm features and secondary causes) is empiric.1 The patient’s symptoms—specifically those most bother-some—should direct your decisions. A plan so guided will also help you manage the patient’s expectations.

Address patients’ prior disappointments

Most patients will have self-treated before coming to see you, and some even will have tried prescribed regimens. Initial treatment of constipation has traditionally involved lifestyle changes (eg, diet, fluid, exercise modification), increased fiber intake, and laxatives. However, evidence supporting use of these modalities in this setting is sparse, and patient surveys often show dissatisfaction with these approaches. For instance, a web-based survey showed that 96% of patients with chronic constipation have tried some form of traditional medication (eg, bulking agents, stool softeners, laxatives).2 Overall, 47% were not satisfied with their current treatment, primarily because of inadequate symptom relief and unwanted side effects.

Furthermore, patient compliance with some therapies is poor because of side effects such as flatulence, distension, and bloating. Two recently published systematic reviews evaluating treatment options for patients with chronic constipation came to similar conclusions.1,3

Below we discuss the ACG Chronic Constipation Task Force conclusions and recommendations.1 Explicit communication with patients about what they can expect will help ensure treatment success.

Prescribe fiber, increase water intake

Just a few clinical trials have evaluated the effects of lifestyle changes on constipation symptoms, and they have generally been poorly designed or involved small numbers of patients (TABLE).4-7

Educating patients about proper nutrition and designating a time for daily defecation are common initial approaches, but efficacy of these strategies in this patient population has not been established (SOR: C).4,5

Exercise has dubious value. Exercise is often recommended as a way to treat constipation because of its purported effect on reducing gastrointestinal (GI) transit time (SOR: C).6 However, uncontrolled studies have found that aerobic exercise does not necessarily decrease transit time and may actually prolong it.6

Increasing water alone generally unhelpful… Few data support the benefits of increased fluid consumption, except for dehydrated patients. In one study, increased intake (to 1 L/d) of water or isotonic fluid had no effect on the stool weight of healthy volunteers.4

…but fiber plus water works. However, in a study involving patients with chronic constipation, a high-fiber diet and 2 L/d of water increased frequency of bowel movements and reduced use of laxatives compared with the same diet and ad libitum fluid intake (P<.001). By binding water, fiber increases stool weight, softens stool, decreases colonic transit time, and increases GI motility.4,5,8,9

You can recommend that patients gradually increase fiber intake over several weeks to a total of 20 g/d to 25 g/d)18 through fiber-rich foods (vegetables [eg, carrots, broccoli, string beans], fruits [eg, peaches, apples, oranges], whole-grain breads, pasta, cereal, etc) (SOR: C) or bulk supplements (eg, psyllium, methylcellulose, and polycarbophil) (SOR: B). In conjunction with other lifestyle modifications, this is a reasonable management decision.11 Because failure to balance the ratio between fiber and fluid can worsen constipation, and even cause intestinal obstruction, tell patients who increase their fiber consumption to also increase their fluid intake (30 mL/kg body weight daily).5,12

Caveats. Few data support the benefits of this approach. Epidemiologic studies show a low prevalence of constipation in countries in which fiber-rich diets are the norm,8 but extrapolating data from healthy populations to constipated patients may not be justified.13 In fact, few data from controlled trials support the use of fiber therapy in patients with constipation. In the uncontrolled Nurses’ Health Study, subjects in the highest quintile of dietary fiber intake (median intake, 20 g/d) were less likely to have constipation than those in the lowest quintile (median intake, 7 g/d).14 This general dearth of evidence led the ACG Chronic Constipation Task Force to conclude that psyllium increases stool frequency in patients with chronic constipation (ACG grade: B) but that there are insufficient data to make a recommendation about the efficacy of calcium polycarbophil, methylcellulose, and bran in this patient population (ACG grade: B).1

Important points for patients. Counsel patients for whom you recommend fiber intake that it may take several weeks for them to experience relief,5,8 and that long-term fiber use may cause abdominal distension, bloating, and flatulence.4,5,8,15 Few serious adverse effects (eg, delayed gastric emptying, anorexia, and iron and calcium malabsorption) are associated with bulking agents; however, fecal impaction may occur in patients with severe colonic inertia.16

Hypersensitivity reactions have been reported in patients who ingest psyllium and in healthcare workers exposed to it.16

Osmotic laxatives may help

When increased fiber intake fails to alleviate symptoms of constipation, patients are often prescribed an osmotic laxative (eg, magnesium hydroxide, magnesium citrate, sodium phosphate, or polyethylene glycol [PEG]) (SOR: B), which promotes water secretion in the intestines.4,8,15 However, several days may pass before the laxatives take effect, and they are indicated only for short-term use in patients with occasional constipation.1

Common adverse effects include abdominal cramping, bloating, and flatulence.4,10,17 More serious adverse effects include hypermagnesemia, hyperphosphatemia, hypercalcemia, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypovolemia, and diarrhea1,16 ; the incidences of these events were not reported.

The ACG Task Force gave PEG and lactulose grade A recommendations, based on the quality of evidence supporting their effectiveness at improving stool frequency and stool consistency in patients with chronic constipation.1 PEG was the only laxative shown in clinical trials to improve bowel movement frequency, stool consistency, and colonic transit time. However, this conclusion was based on analysis of all formulations—PMF-100, PEG 3350, PEG/electrolyte solutions, and high-molecular-weight PEG (PEG 4000); PEG 3350 (Miralax), the only PEG formulation approved by the FDA for use in patients with constipation, is indicated specifically for patients with occasional constipation. The Task Force determined that data were insufficient to make a recommendation for milk of magnesia (ACG grade: B).1

Stimulant laxatives, if all else fails

Stimulants (eg, bisacodyl, cascara, senna, ricinoleic acid) cause rhythmic muscle contractions in the intestines and increase intestinal motility and secretions.4,5,9,15,17 Controlled study data for stimulant laxatives are sparse (SOR: B).18 They work within hours,12,15,17,19 but use them judiciously.9

A common adverse effect is abdominal pain; more serious adverse effects include electrolyte imbalances, allergic reactions, and hepatotoxicity.1,16,20 However, these effects appear to be no more severe or frequent than effects of other constipation treatments. Long-term use can also cause benign pigmentation changes in the colon (Pseudomelanosis coli) and can lead to reduced colonic motility (colonic inertia).12,16

Given safety concerns with long-term use, reserve stimulant laxatives for patients who are refractory to or who cannot tolerate other agents.5,17 You should use them only as needed and for a brief time12 (the general guideline for most over-the-counter products is 1 week or less). The ACG Task Force concluded that data are insufficient to make recommendations for stimulant laxatives (ACG grade: B).1

Fiber or laxatives better?

A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials found that fiber and laxatives increased bowel movement frequency by an overall weighted mean of 1.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.1–1.8) bowel movements per week.21 However, evidence was insufficient to establish whether fiber was superior to laxatives or whether one laxative class was superior to another.

Another meta-analysis found that, in studies lasting 4 weeks or less, fiber supplements and laxatives improved stool frequency (mean increase, 1.9 stool/week) and stool weight (mean increase, 476 g) but that these benefits were not clearly distinguishable from those of placebo (stool frequency, 1 stool; stool weight, 434 g).18

Large, well-designed, comparative trials of treatments for chronic constipation in adults are needed.22 Current literature contains few thoroughly reported studies of fiber and laxative use.18 Additionally, standardized measures to assess the adverse effects and outcomes (effects on quality of life) of specific agents have rarely been incorporated.18,22 Given the problematic safety/tolerability profiles of some laxatives, it is unknown whether they improve quality of life of patients with constipation.18

TABLE

Treatments for chronic constipation

| TREATMENT | EFFICACY | SOR | OUTCOMES MEASURED | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle changes (Increased fluids, designated time for defecation, patient education)4,5,7 | High-fiber diet+2 L/d of water significantly increased bowel movement frequency and decreased laxative use (P<.001) compared with high-fiber diet alone (NNT=NA) | C | Stool weight BM frequency Laxative use | Not evaluated in controlled studies in which numbers of responders were reported |

| Exercise 4,6 | Crossover study of low-intensity physical activity minimally improved symptoms in 5 of 8 patients (NNT=1.6) | C | BM frequency, consistency Straining | Uncontrolled studies show inconsistent effects on stool weight and transit time |

| Increased dietary fiber 4,14 | In uncontrolled Nurses’ Health Study, women with high fiber intake were less likely than those with low intake to report constipation (NNT=NA) | C | BM frequency | Not evaluated in well-designed, controlled studies |

| Bulk fiber laxatives (Psyllium, methylcellulose, polycarbophil, ispaghula, bran, among others)13,18,36-38 | Improve overall bowel function at 4 weeks (NNT=7.5) | B | Bowel function at 4 weeks | Few controlled studies; efficacy results often reported only as mean scores, not as number (or %) of responders Adverse effects included abdominal pain, bloating, and flatulence |

| Osmotic laxatives (Magnesium hydroxide, magnesium citrate, sodium phosphate, polyethylene glycol, among others)4,8,15,30,39-42 | Compared with placebo, greater overall effectiveness, more effective in increasing bowel movement frequency, improving subjective well-being, and promoting complete remission of constipation (NNT=1.3–2.4) | B | Overall effectiveness BM frequency Subjective well-being related to defecation Complete remission of constipation | Few controlled studies; small populations in many studies; efficacy results often reported only as mean scores, not as number (or %) of responders |

| Adverse effects included nausea, abdominal pain or discomfort, bloating, distension, and flatulence | ||||

| Stimulant laxatives (Bisacodyl, cascara, senna, ricinoleic acid, ocusates, among others)4,15,22 | Improve bowel movement frequency (NNT=4–14.3) | B | Bowel movement frequency | Few controlled studies |

| Adverse effects include abdominal cramping, fluid and electrolyte depletion, diarrhea, allergic reactions | ||||

| 5-HT4 receptor agonists (Tegaserod)25-27 | More effective than placebo at relieving symptoms of chronic constipation (NNT=5.5–11.1) | A | Responder rate for CSBMs during first 4 weeks of treatment | Brief episodes of diarrhea, usually mild to moderate, may occur near the start of treatment; Safe for long-term use |

| NA, not applicable; NNT, number needed to treat; SOR, strength of recommendation; CSBM, complete spontaneous bowel movement. | ||||

Novel therapies

Tegaserod

Tegaserod (Zelnorm) is FDA-approved for treatment of women with IBS whose primary bowel symptom is constipation, and for treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation in women and men aged <65.23 The ACG Task Force determined that tegaserod increases the frequency of complete spontaneous bowel movements (CSBM), decreases straining, and improves stool consistency in patients with chronic constipation (ACG grade: A).1 Tegaserod binds with high affinity at human 5-HT4 receptors and augments peristalsis, increases colonic motility along the entire GI tract, and promotes intestinal secretions.23,24 (For more information on tegaserod’s mode of activity, see www.jfponline.com.)

Adverse effects. The most noteworthy adverse effect of tegaserod was diarrhea, occurring as brief episodes that were generally mild (not requiring antidiarrheal drugs), transient (occurring early after initiation of treatment and resolving after a couple of days), and self-limiting.25,26 Results of a single-blind, uncontrolled extension study in which 842 patients were administered tegaserod 2 mg or 6 mg for up to 13 months (total exposure was up to 16 months) were similar to those of shorter term studies, indicating that long-term treatment is safe and well-tolerated.27

Important advice for patients. Although tegaserod is generally well tolerated, counsel patients regarding its potential risk. Ischemic colitis, a vascular disorder that results from reduced blood flow in the colon, appears as a precaution in the current package insert.23 No cases of this condition were reported during clinical trials. Although reports of transient ischemic colitis were reported during postmarketing surveillance, they were not associated with long-term consequences, and they occurred at the expected rate in the general population and lower than the rate observed in IBS patients.23,28 To date, no vascular mechanism has been found that links colonic ischemia with tegaserod use.29 Nevertheless, patients for whom tegaserod is prescribed should be counseled to promptly report any symptoms consistent with this condition, including worsening abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, or bloody diarrhea.23

Lubiprostone

Lubiprostone (Amitiza) is a chloride channel activator that increases secretion of intestinal fluid. This agent significantly increases stool frequency, improves stool form, and decreases straining,30-32 and was recently FDA-approved for the treatment of patients with chronic idiopathic constipation.33 To date, data from lubiprostone clinical trials have not been published in full. As more data become available, it will be interesting to evaluate where this agent fits into the growing treatment armamentarium for chronic constipation.

Drugs in the pipeline

Several additional pharmacologic classes with unique modes of action are under investigation for the treatment of chronic constipation, including opioid antagonists and neurotrophic factors.34

When to use which agent

In the absence of specific guidelines dictating an order of treatment options for patients with chronic constipation, base your decision on such factors as the degree to which symptoms affect a patient’s daily life, results achieved with agents in the past, patient preference, and your clinical judgment and experience ( FIGURE ). Lifestyle modifications and traditional (primarily over-the-counter) therapies are typically the initial approaches for patients with milder symptoms. Patients experiencing moderate to severe constipation-associated symptoms, those who have experienced adverse effects, and those who have not achieved satisfactory relief of constipation should be evaluated for other treatment options, including prescription laxatives, tegaserod, and lubiprostone.

Because of the heterogeneity of this disorder, successful management is patient specific. Positive outcomes may include increased stool frequency, less straining, sense of complete evacuation, resolution of abdominal bloating, and passage of soft, formed stool. Optimally, these positive symptom outcomes will translate into better overall quality of life and the ability to return to normal work and personal activities. Importantly, education and continual open dialogue with the patient are crucial to managing expectations, both for the physician and for the patient.

FIGURE

Chronic primary constipation: Let symptom type and severity direct treatment choices

When referral is indicated

Though most patients with chronic constipation can be treated successfully in the primary care setting,35 a few may require referral to a gastroenterologist. Reasons may include the following:

- Suspicion of defecatory disorders (eg, pelvic floor dyssynergia)

- Lack of sufficient response to empiric treatment

- Worsening symptoms despite treatment

- Development of GI-associated alarm features requiring diagnostic procedures that may not be feasible to conduct in the primary care clinic setting (eg, balloon distension, anorectal manometry, defecography, colonic transit, barium enema, and colonoscopy).8

Ongoing communication with the consulting gastroenterologist is critical to maintaining optimal patient care. Use a referral form to clearly explain whether the patient is being referred for a procedure (eg, specific diagnostic test) or for a consultation (eg, temporary release of the patient to the gastroenterologist to further evaluate potential causes of symptoms); this will increase the likelihood that every-one’s expectations are satisfactorily met.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the editorial assistance of Meera Nathan, PhD, Maribeth Bogush, PhD, and Sophia Shumyatsky, PharmD in the preparation of this manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott D. Bleser, DO, FAAFP, Bellbrook Medical Center, Inc, 4336 State Route 725, Bellbrook, OH 45305-2742. E-mail: [email protected]

- Increased fiber intake through diet (C) or fiber supplements (B) is an appropriate initial therapy for chronic constipation.

- Osmotic and stimulant laxatives may be administered to patients who do not respond to more conservative measures if the limitations of these agents are explained (B).

- Tegaserod, a selective 5-hydroxytryptamine type 4 (5-HT4) receptor partial agonist, is more effective than placebo at relieving symptoms of chronic idiopathic constipation in patients younger than 65 years of age (A).

- Patients with suspected defecation disorders and those with treatment-refractory symptoms should be referred to a gastroenterologist for further evaluation (C).

By the time a patient sees you with a complaint of constipation, chances are she has tried a remedy or 2 and is now looking for something new. However, the abandoned remedies may yet prove useful, depending on the nature of her complaint and on her understanding of how the remedy was supposed to have worked. In this article, we discuss the benefits and limitations of several treatment options in managing a patient’s distinct condition, as assessed in part 1 (page 580).

Symptom-focused treatment

As per the ACG Task Force guidelines, initial treatment of chronic constipation (in the absence of alarm features and secondary causes) is empiric.1 The patient’s symptoms—specifically those most bother-some—should direct your decisions. A plan so guided will also help you manage the patient’s expectations.

Address patients’ prior disappointments

Most patients will have self-treated before coming to see you, and some even will have tried prescribed regimens. Initial treatment of constipation has traditionally involved lifestyle changes (eg, diet, fluid, exercise modification), increased fiber intake, and laxatives. However, evidence supporting use of these modalities in this setting is sparse, and patient surveys often show dissatisfaction with these approaches. For instance, a web-based survey showed that 96% of patients with chronic constipation have tried some form of traditional medication (eg, bulking agents, stool softeners, laxatives).2 Overall, 47% were not satisfied with their current treatment, primarily because of inadequate symptom relief and unwanted side effects.

Furthermore, patient compliance with some therapies is poor because of side effects such as flatulence, distension, and bloating. Two recently published systematic reviews evaluating treatment options for patients with chronic constipation came to similar conclusions.1,3

Below we discuss the ACG Chronic Constipation Task Force conclusions and recommendations.1 Explicit communication with patients about what they can expect will help ensure treatment success.

Prescribe fiber, increase water intake

Just a few clinical trials have evaluated the effects of lifestyle changes on constipation symptoms, and they have generally been poorly designed or involved small numbers of patients (TABLE).4-7

Educating patients about proper nutrition and designating a time for daily defecation are common initial approaches, but efficacy of these strategies in this patient population has not been established (SOR: C).4,5

Exercise has dubious value. Exercise is often recommended as a way to treat constipation because of its purported effect on reducing gastrointestinal (GI) transit time (SOR: C).6 However, uncontrolled studies have found that aerobic exercise does not necessarily decrease transit time and may actually prolong it.6

Increasing water alone generally unhelpful… Few data support the benefits of increased fluid consumption, except for dehydrated patients. In one study, increased intake (to 1 L/d) of water or isotonic fluid had no effect on the stool weight of healthy volunteers.4

…but fiber plus water works. However, in a study involving patients with chronic constipation, a high-fiber diet and 2 L/d of water increased frequency of bowel movements and reduced use of laxatives compared with the same diet and ad libitum fluid intake (P<.001). By binding water, fiber increases stool weight, softens stool, decreases colonic transit time, and increases GI motility.4,5,8,9

You can recommend that patients gradually increase fiber intake over several weeks to a total of 20 g/d to 25 g/d)18 through fiber-rich foods (vegetables [eg, carrots, broccoli, string beans], fruits [eg, peaches, apples, oranges], whole-grain breads, pasta, cereal, etc) (SOR: C) or bulk supplements (eg, psyllium, methylcellulose, and polycarbophil) (SOR: B). In conjunction with other lifestyle modifications, this is a reasonable management decision.11 Because failure to balance the ratio between fiber and fluid can worsen constipation, and even cause intestinal obstruction, tell patients who increase their fiber consumption to also increase their fluid intake (30 mL/kg body weight daily).5,12

Caveats. Few data support the benefits of this approach. Epidemiologic studies show a low prevalence of constipation in countries in which fiber-rich diets are the norm,8 but extrapolating data from healthy populations to constipated patients may not be justified.13 In fact, few data from controlled trials support the use of fiber therapy in patients with constipation. In the uncontrolled Nurses’ Health Study, subjects in the highest quintile of dietary fiber intake (median intake, 20 g/d) were less likely to have constipation than those in the lowest quintile (median intake, 7 g/d).14 This general dearth of evidence led the ACG Chronic Constipation Task Force to conclude that psyllium increases stool frequency in patients with chronic constipation (ACG grade: B) but that there are insufficient data to make a recommendation about the efficacy of calcium polycarbophil, methylcellulose, and bran in this patient population (ACG grade: B).1

Important points for patients. Counsel patients for whom you recommend fiber intake that it may take several weeks for them to experience relief,5,8 and that long-term fiber use may cause abdominal distension, bloating, and flatulence.4,5,8,15 Few serious adverse effects (eg, delayed gastric emptying, anorexia, and iron and calcium malabsorption) are associated with bulking agents; however, fecal impaction may occur in patients with severe colonic inertia.16

Hypersensitivity reactions have been reported in patients who ingest psyllium and in healthcare workers exposed to it.16

Osmotic laxatives may help

When increased fiber intake fails to alleviate symptoms of constipation, patients are often prescribed an osmotic laxative (eg, magnesium hydroxide, magnesium citrate, sodium phosphate, or polyethylene glycol [PEG]) (SOR: B), which promotes water secretion in the intestines.4,8,15 However, several days may pass before the laxatives take effect, and they are indicated only for short-term use in patients with occasional constipation.1

Common adverse effects include abdominal cramping, bloating, and flatulence.4,10,17 More serious adverse effects include hypermagnesemia, hyperphosphatemia, hypercalcemia, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypovolemia, and diarrhea1,16 ; the incidences of these events were not reported.

The ACG Task Force gave PEG and lactulose grade A recommendations, based on the quality of evidence supporting their effectiveness at improving stool frequency and stool consistency in patients with chronic constipation.1 PEG was the only laxative shown in clinical trials to improve bowel movement frequency, stool consistency, and colonic transit time. However, this conclusion was based on analysis of all formulations—PMF-100, PEG 3350, PEG/electrolyte solutions, and high-molecular-weight PEG (PEG 4000); PEG 3350 (Miralax), the only PEG formulation approved by the FDA for use in patients with constipation, is indicated specifically for patients with occasional constipation. The Task Force determined that data were insufficient to make a recommendation for milk of magnesia (ACG grade: B).1

Stimulant laxatives, if all else fails

Stimulants (eg, bisacodyl, cascara, senna, ricinoleic acid) cause rhythmic muscle contractions in the intestines and increase intestinal motility and secretions.4,5,9,15,17 Controlled study data for stimulant laxatives are sparse (SOR: B).18 They work within hours,12,15,17,19 but use them judiciously.9

A common adverse effect is abdominal pain; more serious adverse effects include electrolyte imbalances, allergic reactions, and hepatotoxicity.1,16,20 However, these effects appear to be no more severe or frequent than effects of other constipation treatments. Long-term use can also cause benign pigmentation changes in the colon (Pseudomelanosis coli) and can lead to reduced colonic motility (colonic inertia).12,16

Given safety concerns with long-term use, reserve stimulant laxatives for patients who are refractory to or who cannot tolerate other agents.5,17 You should use them only as needed and for a brief time12 (the general guideline for most over-the-counter products is 1 week or less). The ACG Task Force concluded that data are insufficient to make recommendations for stimulant laxatives (ACG grade: B).1

Fiber or laxatives better?

A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials found that fiber and laxatives increased bowel movement frequency by an overall weighted mean of 1.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.1–1.8) bowel movements per week.21 However, evidence was insufficient to establish whether fiber was superior to laxatives or whether one laxative class was superior to another.

Another meta-analysis found that, in studies lasting 4 weeks or less, fiber supplements and laxatives improved stool frequency (mean increase, 1.9 stool/week) and stool weight (mean increase, 476 g) but that these benefits were not clearly distinguishable from those of placebo (stool frequency, 1 stool; stool weight, 434 g).18

Large, well-designed, comparative trials of treatments for chronic constipation in adults are needed.22 Current literature contains few thoroughly reported studies of fiber and laxative use.18 Additionally, standardized measures to assess the adverse effects and outcomes (effects on quality of life) of specific agents have rarely been incorporated.18,22 Given the problematic safety/tolerability profiles of some laxatives, it is unknown whether they improve quality of life of patients with constipation.18

TABLE

Treatments for chronic constipation

| TREATMENT | EFFICACY | SOR | OUTCOMES MEASURED | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle changes (Increased fluids, designated time for defecation, patient education)4,5,7 | High-fiber diet+2 L/d of water significantly increased bowel movement frequency and decreased laxative use (P<.001) compared with high-fiber diet alone (NNT=NA) | C | Stool weight BM frequency Laxative use | Not evaluated in controlled studies in which numbers of responders were reported |

| Exercise 4,6 | Crossover study of low-intensity physical activity minimally improved symptoms in 5 of 8 patients (NNT=1.6) | C | BM frequency, consistency Straining | Uncontrolled studies show inconsistent effects on stool weight and transit time |

| Increased dietary fiber 4,14 | In uncontrolled Nurses’ Health Study, women with high fiber intake were less likely than those with low intake to report constipation (NNT=NA) | C | BM frequency | Not evaluated in well-designed, controlled studies |

| Bulk fiber laxatives (Psyllium, methylcellulose, polycarbophil, ispaghula, bran, among others)13,18,36-38 | Improve overall bowel function at 4 weeks (NNT=7.5) | B | Bowel function at 4 weeks | Few controlled studies; efficacy results often reported only as mean scores, not as number (or %) of responders Adverse effects included abdominal pain, bloating, and flatulence |

| Osmotic laxatives (Magnesium hydroxide, magnesium citrate, sodium phosphate, polyethylene glycol, among others)4,8,15,30,39-42 | Compared with placebo, greater overall effectiveness, more effective in increasing bowel movement frequency, improving subjective well-being, and promoting complete remission of constipation (NNT=1.3–2.4) | B | Overall effectiveness BM frequency Subjective well-being related to defecation Complete remission of constipation | Few controlled studies; small populations in many studies; efficacy results often reported only as mean scores, not as number (or %) of responders |

| Adverse effects included nausea, abdominal pain or discomfort, bloating, distension, and flatulence | ||||

| Stimulant laxatives (Bisacodyl, cascara, senna, ricinoleic acid, ocusates, among others)4,15,22 | Improve bowel movement frequency (NNT=4–14.3) | B | Bowel movement frequency | Few controlled studies |

| Adverse effects include abdominal cramping, fluid and electrolyte depletion, diarrhea, allergic reactions | ||||

| 5-HT4 receptor agonists (Tegaserod)25-27 | More effective than placebo at relieving symptoms of chronic constipation (NNT=5.5–11.1) | A | Responder rate for CSBMs during first 4 weeks of treatment | Brief episodes of diarrhea, usually mild to moderate, may occur near the start of treatment; Safe for long-term use |

| NA, not applicable; NNT, number needed to treat; SOR, strength of recommendation; CSBM, complete spontaneous bowel movement. | ||||

Novel therapies

Tegaserod

Tegaserod (Zelnorm) is FDA-approved for treatment of women with IBS whose primary bowel symptom is constipation, and for treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation in women and men aged <65.23 The ACG Task Force determined that tegaserod increases the frequency of complete spontaneous bowel movements (CSBM), decreases straining, and improves stool consistency in patients with chronic constipation (ACG grade: A).1 Tegaserod binds with high affinity at human 5-HT4 receptors and augments peristalsis, increases colonic motility along the entire GI tract, and promotes intestinal secretions.23,24 (For more information on tegaserod’s mode of activity, see www.jfponline.com.)

Adverse effects. The most noteworthy adverse effect of tegaserod was diarrhea, occurring as brief episodes that were generally mild (not requiring antidiarrheal drugs), transient (occurring early after initiation of treatment and resolving after a couple of days), and self-limiting.25,26 Results of a single-blind, uncontrolled extension study in which 842 patients were administered tegaserod 2 mg or 6 mg for up to 13 months (total exposure was up to 16 months) were similar to those of shorter term studies, indicating that long-term treatment is safe and well-tolerated.27

Important advice for patients. Although tegaserod is generally well tolerated, counsel patients regarding its potential risk. Ischemic colitis, a vascular disorder that results from reduced blood flow in the colon, appears as a precaution in the current package insert.23 No cases of this condition were reported during clinical trials. Although reports of transient ischemic colitis were reported during postmarketing surveillance, they were not associated with long-term consequences, and they occurred at the expected rate in the general population and lower than the rate observed in IBS patients.23,28 To date, no vascular mechanism has been found that links colonic ischemia with tegaserod use.29 Nevertheless, patients for whom tegaserod is prescribed should be counseled to promptly report any symptoms consistent with this condition, including worsening abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, or bloody diarrhea.23

Lubiprostone

Lubiprostone (Amitiza) is a chloride channel activator that increases secretion of intestinal fluid. This agent significantly increases stool frequency, improves stool form, and decreases straining,30-32 and was recently FDA-approved for the treatment of patients with chronic idiopathic constipation.33 To date, data from lubiprostone clinical trials have not been published in full. As more data become available, it will be interesting to evaluate where this agent fits into the growing treatment armamentarium for chronic constipation.

Drugs in the pipeline

Several additional pharmacologic classes with unique modes of action are under investigation for the treatment of chronic constipation, including opioid antagonists and neurotrophic factors.34

When to use which agent

In the absence of specific guidelines dictating an order of treatment options for patients with chronic constipation, base your decision on such factors as the degree to which symptoms affect a patient’s daily life, results achieved with agents in the past, patient preference, and your clinical judgment and experience ( FIGURE ). Lifestyle modifications and traditional (primarily over-the-counter) therapies are typically the initial approaches for patients with milder symptoms. Patients experiencing moderate to severe constipation-associated symptoms, those who have experienced adverse effects, and those who have not achieved satisfactory relief of constipation should be evaluated for other treatment options, including prescription laxatives, tegaserod, and lubiprostone.

Because of the heterogeneity of this disorder, successful management is patient specific. Positive outcomes may include increased stool frequency, less straining, sense of complete evacuation, resolution of abdominal bloating, and passage of soft, formed stool. Optimally, these positive symptom outcomes will translate into better overall quality of life and the ability to return to normal work and personal activities. Importantly, education and continual open dialogue with the patient are crucial to managing expectations, both for the physician and for the patient.

FIGURE

Chronic primary constipation: Let symptom type and severity direct treatment choices

When referral is indicated

Though most patients with chronic constipation can be treated successfully in the primary care setting,35 a few may require referral to a gastroenterologist. Reasons may include the following:

- Suspicion of defecatory disorders (eg, pelvic floor dyssynergia)

- Lack of sufficient response to empiric treatment

- Worsening symptoms despite treatment

- Development of GI-associated alarm features requiring diagnostic procedures that may not be feasible to conduct in the primary care clinic setting (eg, balloon distension, anorectal manometry, defecography, colonic transit, barium enema, and colonoscopy).8

Ongoing communication with the consulting gastroenterologist is critical to maintaining optimal patient care. Use a referral form to clearly explain whether the patient is being referred for a procedure (eg, specific diagnostic test) or for a consultation (eg, temporary release of the patient to the gastroenterologist to further evaluate potential causes of symptoms); this will increase the likelihood that every-one’s expectations are satisfactorily met.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the editorial assistance of Meera Nathan, PhD, Maribeth Bogush, PhD, and Sophia Shumyatsky, PharmD in the preparation of this manuscript.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott D. Bleser, DO, FAAFP, Bellbrook Medical Center, Inc, 4336 State Route 725, Bellbrook, OH 45305-2742. E-mail: [email protected]

1. Brandt LJ, Schoenfeld P, Prather CM, Quigley EMM, Schiller LR, Talley NJ. Evidenced-based position statement on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100(suppl):S1-S21.

2. Schiller LR, Dennis E, Toth G. An internet-based survey of the prevalence and symptom spectrum of chronic constipation [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:S234.-

3. Ramkumar D, Rao SSC. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:936-971.

4. Pampati V, Fogel R. Treatment options for primary constipation. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2004;7:225-233.

5. Wald A. Constipation. Med Clin North Am 2000;84:1231-1246.

6. Meshkinpour H, Selod S, Movahedi H, et al. Effects of regular exercise in management of chronic idiopathic constipation. Dig Dis Sci 1998;43:2379-2383.

7. Anti M, Pignataro G, Armuzzi A, et al. Water supplementation enhances the effect of high-fiber diet on stool frequency and laxative consumption in adult patients with functional constipation. Hepatogastroenterology 1998;45:727-732.

8. Locke GR, III, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. AGA technical review on constipation. Gastroenterol 2000;119:1766-1778.

9. Borum ML. Constipation: evaluation and management. Primary Care 2001;28:577-590.

10. Talley NJ. Management of chronic constipation. Rev Gastroenterol Disord 2004;4:18-24.

11. Locke GR, III, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. AGA Medical Position Statement: guidelines on constipation. Gastroenterol 2000;119:1761-1766.

12. Doughty DB. When fiber is not enough: current thinking on constipation management. Ostomy Wound Manage 2002;48:30-41.

13. Cheskin LJ, Kamal N, Crowell MD, Schuster MM, Whitehead WE. Mechanisms of constipation in older persons and effects of fiber compared with placebo. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:666-669.

14. Dukas L, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL. Association between physical activity, fiber intake, and other lifestyle variables and constipation in a study of women. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:1790-1796.

15. Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1360-1368.

16. Xing JH, Soffer EE. Adverse effects of laxatives. Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44:1201-1209.

17. Schiller LR. Review article: the therapy of constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:749-763.

18. Jones MP, Talley NJ, Nuyts G, Dubois D. Lack of objective evidence of efficacy of laxatives in chronic constipation. Dig Dis Sci 2002;47:2222-2230.

19. DiPalma JA. Current treatment options for chronic constipation. Rev Gastroenterol Disord 2004;(suppl 2):S34-S42.

20. Gattuso JM, Kamm MA. Adverse effects of drugs used in the management of constipation and diarrhoea. Drug Saf 1994;10:47-65.

21. Tramonte SM, Brand MB, Mulrow CD, Amato MG, O’Keefe ME, Ramirez G. The treatment of chronic constipation in adults. A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 1997;12:15-24.

22. Petticrew M, Rodgers M, Booth A. Effectiveness of laxatives in adults. Qual Health Care 2001;10:268-273.

23. Zelnorm (tegaserod maleate) tablets [prescribing information]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis; August 2004.

24. Appel-Dingemanse S. Clinical pharmacokinetics of tegaserod, a serotonin 5-HT4 receptor partial agonist with promotile activity. Clin Pharmacokinet 2002;41:1021-1042.

25. Johanson JF, Wald A, Tougas G, et al. Effect of tegaserod in chronic constipation: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:796-805.

26. Kamm MA, Muller-Lissner S, Talley NJ, et al. Tegaserod for the treatment of chronic constipation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multinational study. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:362-372.

27. Mueller-Lissner S, Kamm M, Haeck P, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of tegaserod in chronic constipation (CC) [abstract]. Gastroenterol 2004;126(Suppl 2).-

28. Schoenfeld P. Review article: the safety profile of tegaserod. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20(suppl 7):25-30.

29. Joelsson BE, Shetzline MA, Cunningham S. Ischemic colitis associated with use of tegaserod [reply]. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1363-1364.

30. Johanson JF, Gargano MA, Holland PC, Patchen ML, Ueno R. Phase III, randomized withdrawal study of RU-0211, a novel chloride channel activator for the treatment of constipation [abstract]. Gastroenterol 2004;126(suppl 2):A100.-

31. Johanson JF, Gargano MA, Holland PC, Patchen ML, Ueno R. Phase III efficacy and safety of RU-0211, a novel chloride channel activator, for the treatment of constipation [abstract]. Gastroenterol 2003;124:A104.-

32. Johanson JF, Gargano MA, Patchen ML, Ueno R. Efficacy and safety of a novel compound, RU-0211, for the treatment of constipation [abstract]. Gastroenterol 2002;122:A-315.

33. Amitiza (lubiprostone) soft gelatin capsules [prescribing information]. Bethesda, Md: Sucampo Pharmaceuticals; 2006.

34. Schiller LR. New and emerging treatment options for chronic constipation. Rev Gastroenterol Dis 2004;4:S43-S51.

35. Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Physician visits in the United States for constipation: 1958 to 1986. Dig Dis Sci 1989;34:606-611.

36. Dettmar PW, Sykes J. A multi-centre, general practice comparison of ispaghula husk with lactulose and other laxatives in the treatment of simple constipation. Curr Med Res Opin. 1998;14:227-233.

37. Badiali D, Corazziari E, Habib FI, et al. Effect of wheat bran in treatment of chronic nonorganic constipation: a double-blind controlled trial. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:349-356.

38. McRorie JW, Daggy BP, Morel JG, Diersing PS, Miner PB, Robinson M. Psyllium is superior to docusate sodium for treatment of chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998;12:491-497.

39. Klauser AG, Muhldorfer BE, Voderholzer WA, Wenzel G, Muller-Lissner SA. Polyethylene glycol 4000 for slow transit constipation. Z Gastroenterol 1995;33:5-8.

40. Cleveland MV, Flavin DP, Ruben RA, Epstein RM, Clark GE. New polyethylene glycol laxative for treatment of constipation in adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. South Med J 2001;94:478-481.

41. Corazziari E, Badiali D, Bazzocchi G, et al. Long-term efficacy, safety, and tolerability of low daily doses of isosmotic polyethylene glycol electrolyte balanced solution (PMF-100) in the treatment of functional chronic constipation. Gut 2000;46:522-526.

42. Corazziari E, Badiali D, Habib FI, et al. Small volume isosmotic polyethylene glycol electrolyte balanced solution (PMF-100) in treatment of chronic nonorganic constipation. Dig Dis Sci 1996;41:1636-1642.

1. Brandt LJ, Schoenfeld P, Prather CM, Quigley EMM, Schiller LR, Talley NJ. Evidenced-based position statement on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100(suppl):S1-S21.

2. Schiller LR, Dennis E, Toth G. An internet-based survey of the prevalence and symptom spectrum of chronic constipation [abstract]. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:S234.-

3. Ramkumar D, Rao SSC. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:936-971.

4. Pampati V, Fogel R. Treatment options for primary constipation. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2004;7:225-233.

5. Wald A. Constipation. Med Clin North Am 2000;84:1231-1246.

6. Meshkinpour H, Selod S, Movahedi H, et al. Effects of regular exercise in management of chronic idiopathic constipation. Dig Dis Sci 1998;43:2379-2383.

7. Anti M, Pignataro G, Armuzzi A, et al. Water supplementation enhances the effect of high-fiber diet on stool frequency and laxative consumption in adult patients with functional constipation. Hepatogastroenterology 1998;45:727-732.

8. Locke GR, III, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. AGA technical review on constipation. Gastroenterol 2000;119:1766-1778.

9. Borum ML. Constipation: evaluation and management. Primary Care 2001;28:577-590.

10. Talley NJ. Management of chronic constipation. Rev Gastroenterol Disord 2004;4:18-24.

11. Locke GR, III, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. AGA Medical Position Statement: guidelines on constipation. Gastroenterol 2000;119:1761-1766.

12. Doughty DB. When fiber is not enough: current thinking on constipation management. Ostomy Wound Manage 2002;48:30-41.

13. Cheskin LJ, Kamal N, Crowell MD, Schuster MM, Whitehead WE. Mechanisms of constipation in older persons and effects of fiber compared with placebo. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:666-669.

14. Dukas L, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL. Association between physical activity, fiber intake, and other lifestyle variables and constipation in a study of women. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:1790-1796.

15. Lembo A, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1360-1368.

16. Xing JH, Soffer EE. Adverse effects of laxatives. Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44:1201-1209.

17. Schiller LR. Review article: the therapy of constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:749-763.

18. Jones MP, Talley NJ, Nuyts G, Dubois D. Lack of objective evidence of efficacy of laxatives in chronic constipation. Dig Dis Sci 2002;47:2222-2230.

19. DiPalma JA. Current treatment options for chronic constipation. Rev Gastroenterol Disord 2004;(suppl 2):S34-S42.

20. Gattuso JM, Kamm MA. Adverse effects of drugs used in the management of constipation and diarrhoea. Drug Saf 1994;10:47-65.

21. Tramonte SM, Brand MB, Mulrow CD, Amato MG, O’Keefe ME, Ramirez G. The treatment of chronic constipation in adults. A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 1997;12:15-24.

22. Petticrew M, Rodgers M, Booth A. Effectiveness of laxatives in adults. Qual Health Care 2001;10:268-273.

23. Zelnorm (tegaserod maleate) tablets [prescribing information]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis; August 2004.

24. Appel-Dingemanse S. Clinical pharmacokinetics of tegaserod, a serotonin 5-HT4 receptor partial agonist with promotile activity. Clin Pharmacokinet 2002;41:1021-1042.

25. Johanson JF, Wald A, Tougas G, et al. Effect of tegaserod in chronic constipation: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:796-805.

26. Kamm MA, Muller-Lissner S, Talley NJ, et al. Tegaserod for the treatment of chronic constipation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multinational study. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:362-372.

27. Mueller-Lissner S, Kamm M, Haeck P, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of tegaserod in chronic constipation (CC) [abstract]. Gastroenterol 2004;126(Suppl 2).-

28. Schoenfeld P. Review article: the safety profile of tegaserod. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20(suppl 7):25-30.

29. Joelsson BE, Shetzline MA, Cunningham S. Ischemic colitis associated with use of tegaserod [reply]. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1363-1364.

30. Johanson JF, Gargano MA, Holland PC, Patchen ML, Ueno R. Phase III, randomized withdrawal study of RU-0211, a novel chloride channel activator for the treatment of constipation [abstract]. Gastroenterol 2004;126(suppl 2):A100.-

31. Johanson JF, Gargano MA, Holland PC, Patchen ML, Ueno R. Phase III efficacy and safety of RU-0211, a novel chloride channel activator, for the treatment of constipation [abstract]. Gastroenterol 2003;124:A104.-

32. Johanson JF, Gargano MA, Patchen ML, Ueno R. Efficacy and safety of a novel compound, RU-0211, for the treatment of constipation [abstract]. Gastroenterol 2002;122:A-315.

33. Amitiza (lubiprostone) soft gelatin capsules [prescribing information]. Bethesda, Md: Sucampo Pharmaceuticals; 2006.

34. Schiller LR. New and emerging treatment options for chronic constipation. Rev Gastroenterol Dis 2004;4:S43-S51.

35. Sonnenberg A, Koch TR. Physician visits in the United States for constipation: 1958 to 1986. Dig Dis Sci 1989;34:606-611.

36. Dettmar PW, Sykes J. A multi-centre, general practice comparison of ispaghula husk with lactulose and other laxatives in the treatment of simple constipation. Curr Med Res Opin. 1998;14:227-233.

37. Badiali D, Corazziari E, Habib FI, et al. Effect of wheat bran in treatment of chronic nonorganic constipation: a double-blind controlled trial. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:349-356.

38. McRorie JW, Daggy BP, Morel JG, Diersing PS, Miner PB, Robinson M. Psyllium is superior to docusate sodium for treatment of chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1998;12:491-497.

39. Klauser AG, Muhldorfer BE, Voderholzer WA, Wenzel G, Muller-Lissner SA. Polyethylene glycol 4000 for slow transit constipation. Z Gastroenterol 1995;33:5-8.

40. Cleveland MV, Flavin DP, Ruben RA, Epstein RM, Clark GE. New polyethylene glycol laxative for treatment of constipation in adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. South Med J 2001;94:478-481.

41. Corazziari E, Badiali D, Bazzocchi G, et al. Long-term efficacy, safety, and tolerability of low daily doses of isosmotic polyethylene glycol electrolyte balanced solution (PMF-100) in the treatment of functional chronic constipation. Gut 2000;46:522-526.

42. Corazziari E, Badiali D, Habib FI, et al. Small volume isosmotic polyethylene glycol electrolyte balanced solution (PMF-100) in treatment of chronic nonorganic constipation. Dig Dis Sci 1996;41:1636-1642.

The Journal of Family Practice ©2006 Dowden Health Media

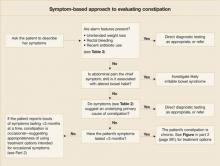

Practical symptom-based evaluation of chronic constipation

- A symptom-based approach is the best means for diagnosing chronic constipation. Extensive diagnostic testing is seldom necessary unless alarm features are present (C).

- Encourage routine colon cancer screening tests for all patients aged 50 years or older (C).

When a patient tells you she is constipated, what does she really mean? You would think that a report so common about a complaint so universal would be immediately clear. But, in fact, there is no standard, widely accepted definition.

Researchers define constipation by diagnostic criteria (eg, Rome II).1

Recommendation grades based on the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Chronic Constipation Task Force are presented on our web site (TABLE W1),4 as are the strength of recommendations taxonomy (SORT) grades for evidence (TABLE W2).5

Methods