User login

Hereditary angioedema due to deficiency of C1 inhibitor is a rare autosomal dominant disease that can be life-threatening. It affects about 1 in 50,000 people,1 or about 6,000 people in the United States. There are no known differences in prevalence by ethnicity or sex. A form of hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels has also recently been identified.

Despite a growing awareness of hereditary angioedema in the medical community, repeated surveys have found an average gap of 10 years between the first appearance of symptoms and the correct diagnosis. In view of the risk of morbidity and death, recognizing this disease sooner is critical.

This article will discuss how to recognize hereditary angioedema and how to differentiate it from other forms of recurring angioedema. We will also review its acute and long-term management, with special attention to new therapies and clinical challenges.

EPISODES OF SWELLING WITHOUT HIVES

Hereditary angioedema involves recurrent episodes of nonpruritic, nonpitting, subcutaneous and submucosal edema that can affect the face, tongue, larynx, trunk, extremities, bowels, or genitals. Attacks typically follow a predictable course: swelling that increases slowly and continuously for 24 hours and then gradually subsides over the next 48 to 72 hours. Attacks that involve the oropharynx, larynx, or abdomen carry the highest risk of morbidity and death.1

The frequency and severity of attacks are highly variable and unpredictable. A few patients have no attacks, a few have two attacks per week, and most fall in between.

Hives suggests an allergic or idiopathic rather than hereditary cause and will not be discussed here in detail. A history of angioedema that was rapidly aborted by antihistamines, corticosteroids, or epinephrine also suggests an allergic rather than hereditary cause.

UNCHECKED BRADYKININ PRODUCTION

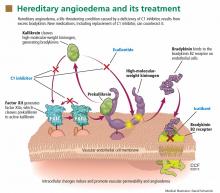

Substantial evidence indicates that hereditary angioedema results from extravasation of plasma into deeper cutaneous or mucosal compartments as a result of overproduction of the vasoactive mediator bradykinin (Figure 1).

Activated factor XII cleaves plasma prekallikrein to generate active plasma kallikrein (which, in turn, activates more factor XII).2 Once generated, plasma kallikrein cleaves high-molecular-weight kininogen, releasing bradykinin. Bradykinin binds to the B2 bradykinin receptor on endothelial cells, increasing the permeability of the endothelium.

Normally, C1 inhibitor helps control bradykinin production by inhibiting plasma kallikrein and activated factor XII. Without enough C1 inhibitor, the contact system is uninhibited and results in bradykinin being inappropriately generated.

Because the attacks of hereditary angioedema involve excessive bradykinin, they do not respond to the usual treatments for anaphylaxis and allergic angioedema (which involve mast cell degranulation), such as antihistamines, corticosteroids, and epinephrine.

TWO TYPES OF HEREDITARY ANGIOEDEMA

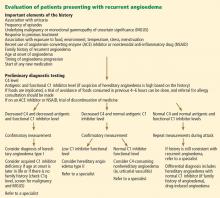

Figure 2 shows the evaluation of patients with suspected hereditary angioedema.

Hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency

The classic forms of hereditary angioedema (types I and II) involve loss-of-function mutations in SERPING1—the gene that encodes for C1 inhibitor—resulting in low levels of functional C1 inhibitor.3 The mutation is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern; however, in about 25% of cases, it appears to arise spontaneously,4 so a family history is not required for diagnosis.

Although C1 inhibitor deficiency is present from birth, the clinical disease most commonly presents for the first time when the patient is of school age. Half of patients have their first episode in the first decade of life, and another one-third first develop symptoms over the next 10 years.5

Clinically, types I and II are indistinguishable. Type I, accounting for 85% of cases,1 results from low production of C1 inhibitor. Laboratory studies reveal low antigenic and functional levels of C1 inhibitor.

In type II, the mutant C1 inhibitor protein is present but dysfunctional and unable to inhibit target proteases. On laboratory testing, the functional level of C1 inhibitor is low but its antigenic level is normal (Table 1). Function can be tested by either chromogenic assay or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; the former is preferred because it is more sensitive.6

Because C1 inhibitor deficiency results in chronic activation of the complement system, patients with type I or II disease usually have low C4 levels regardless of disease activity, making measuring C4 the most economical screening test. When suspicion for hereditary angioedema is high, based on the presentation and family and clinical history, measuring antigenic and functional C1 inhibitor levels and C4 simultaneously is more efficient.

Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels

Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels is also inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. It is often estrogen-sensitive, making it more severe in women. Symptoms tend to develop slightly later in life than in type I or II disease.7

Angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels has been associated with factor XII mutations in a minority of cases, but most patients do not have a specific laboratory abnormality. Because there is no specific laboratory profile, the diagnosis is based on clinical criteria. Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels should be considered in patients who have recurrent angioedema, normal C4, normal antigenic and functional C1 inhibitor levels, a lack of response to high-dose antihistamines, and either a family history of angioedema without hives or a known factor XII mutation.7 However, other forms of angioedema (allergic, drug-induced, and idiopathic) should also be considered, as C4 and C1 inhibitor levels are normal in these forms as well.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS: OTHER TYPES OF ANGIOEDEMA

Acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency

Symptoms of acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency resemble those of hereditary angioedema but typically do not emerge until the fourth decade of life or later, and patients have no family history of the condition. It is often associated with other diseases, most commonly B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, which cause uncontrolled complement activation and consumption of C1 inhibitor.

In some patients, autoantibodies to C1 inhibitor develop, greatly reducing its effectiveness and resulting in enhanced consumption. The autoantibody is often associated with a monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance. The presence of a C1 inhibitor autoantibody does not preclude the presence of an underlying disorder, and vice versa.

Laboratory studies reveal low C4, low C1-inhibitor antigenic and functional levels, and usually a low C1q level owing to consumption of complement. Autoantibodies to C1 inhibitor can be detected by laboratory testing.

Because of the association with autoimmune disease and malignant disorders (especially B-cell malignancy), a patient diagnosed with acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency should be further evaluated for underlying conditions.

Allergic angioedema

Allergic angioedema results from preformed antigen-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies that stimulate mast cells to degranulate when patients are exposed to a particular allergen—most commonly food, insect venom, latex, or drugs. IgE-mediated histamine release causes swelling, as histamine is a potent vasodilator.

Symptoms often begin within 2 hours of exposure to the allergen and generally include concurrent urticaria and swelling that last less than 24 hours. Unlike in hereditary angioedema, the swelling responds to antihistamines and corticosteroids. When very severe, these symptoms may also be accompanied by bronchoconstriction and gastrointestinal symptoms, especially if the allergen is ingested.

Histamine-mediated angioedema may also be associated with exercise as part of a syndrome called exercise-induced anaphylaxis or angioedema.

Drug-induced angioedema

Drug-induced angioedema is typically associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Angioedema associated with ACE inhibitors is estimated to affect 0.1% to 6% of patients taking these medications, with African Americans being at significantly higher risk. Although 25% of affected patients develop symptoms of angioedema within the first month of taking the drugs, some tolerate them for as long as 10 years before the first episode.9 The swelling is not allergic or histamine-related. ACE normally degrades bradykinin; therefore, inhibiting ACE leads to accumulation of bradykinin. Because all ACE inhibitors have this effect, this class of drug should be discontinued in any patient who develops isolated angioedema.

NSAID-induced angioedema is often accompanied by other symptoms, including urticaria, rhinitis, cough, hoarseness, or breathlessness.10 The mechanism of NSAID-induced angioedema involves cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 (and to a lesser extent COX-2) inhibition. All NSAIDs (and aspirin) should be avoided in patients with recurrent angioedema. Specific COX-2 inhibitors, while theoretically capable of causing angioedema by the same mechanism, are generally well tolerated in patients who have had COX-1 inhibitor reactions.

Idiopathic angioedema

If no clear cause of recurrent angioedema (at least three episodes in a year) can be found, it is labeled idiopathic.11 Some patients with idiopathic angioedema fail to benefit from high doses of antihistamines, suggesting that the cause is bradykinin-mediated.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF HEREDITARY ANGIOEDEMA

Attacks may start at one site and progress to involve additional sites.

Prodromal symptoms may begin up to several days before an attack and include tingling, warmth, burning, or itching at the affected site; increased fatigue or malaise; nausea, abdominal distention, or gassiness; or increased hunger, particularly before an abdominal attack.5 The most characteristic prodromal symptom is erythema marginatum—a raised, serpiginous, nonpruritic rash on the trunk, arms, and legs but often sparing the face.

Abdominal attacks are easily confused with acute abdomen

Almost half of attacks involve the abdomen, and almost all patients with type I or II disease experience at least one such attack.12 Symptoms can include severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Abdominal attacks account for many emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and surgical procedures for acute abdomen; about one-third of patients with undiagnosed hereditary angioedema undergo an unnecessary surgery during an abdominal attack. Angioedema of the gastrointestinal tract can result in enough plasma extravasation and vasodilation to cause hypovolemic shock.

Eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection may alleviate abdominal attacks.13

Attacks of the extremities can be painful and disabling

Attacks of the extremities affect 96% of patients12 and can be very disfiguring and disabling. Driving or using the phone is often difficult when the hands are affected. When feet are involved, walking and standing become painful. While these symptoms rarely result in a lengthy hospitalization, they interfere with work and school and require immediate medical attention because they can progress to other parts of the body.

Laryngeal attacks are life-threatening

About half of patients with hereditary angioedema have an attack of laryngeal edema at some point in their lives.12 If not effectively managed, laryngeal angioedema can progress to asphyxiation. A survey of family history in 58 patients with hereditary angioedema suggested a 40% incidence of asphyxiation in untreated laryngeal attacks, and 25% to 30% of patients are estimated to have died of laryngeal edema before effective treatment became available.14

Symptoms of a laryngeal attack include change in voice, hoarseness, trouble swallowing, shortness of breath, and wheezing. Physicians must recognize these symptoms quickly and give effective treatment early in the attack to prevent morbidity and death.

Establishing an airway can be life-saving in the absence of effective therapy, but extensive swelling of the upper airway can make intubation extremely difficult.

Genitourinary attacks also occur

Attacks involving the scrotum and labia have been reported in up to two-thirds of patients with hereditary angioedema at some point in their lives. Attacks involving the bladder and kidneys have also been reported but are less common, affecting about 5% of patients.12 Genitourinary attacks may be triggered by local trauma, such as horseback riding or sexual intercourse, although no trigger may be evident.

MANAGING ACUTE ATTACKS

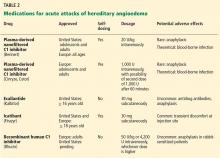

The goals of treatment are to alleviate acute exacerbations with on-demand treatment and to reduce the number of attacks with prophylaxis. Therapy should be individualized to each patient’s needs. Treatments have advanced greatly in the last several years, and new medications for treating acute attacks and preventing attacks have shown great promise (Figure 3, Table 2).

Patients tend to have recurrent symptoms interspersed with periods of health, suggesting that attacks ought to have identifiable triggers, although in most, no trigger is evident. The most commonly identified are local trauma (including medical and dental procedures), emotional stress, and acute infection. Disease severity may be worsened by menstruation, estrogen-containing oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, ACE inhibitors, and NSAIDs.

It is critical that attacks be treated with an effective medication as soon as possible. Consensus guidelines state that all patients with hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency, even if they are still asymptomatic, should have access to at least one of the drugs approved for on-demand treatment.15 The guidelines further state that whenever possible, “patients should have the on-demand medicine to treat acute attacks at home and should be trained to self-administer these medicines.”15

Plasma-derived C1 inhibitors

Several plasma-derived C1 inhibitors are available (Cinryze, Berinert, Cetor). They are prepared from fractionated plasma obtained from donors, then pasteurized and nanofiltered.

Berinert and Cinryze were each found to be superior to placebo in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials: attacks usually resolved 30 to 60 minutes after intravenous injection.16,17 Berinert 20 U/kg is associated with the onset of symptom relief as early as half an hour after administration, compared with 1.5 hours with placebo. Early use (at the onset of symptoms) of a plasma-derived C1 inhibitor in a low dose (500 U) can also be effective.18,19 Efficacy appears to be consistent at all sites of attack involvement, including laryngeal edema. Safety and efficacy have been demonstrated during pregnancy and lactation and in young children and babies.20

Plasma-derived C1 inhibitors can be self-administered. The safety and efficacy of self-administration (under physician supervision) were demonstrated in a study of Cinryze and Cetor, in which attack duration, pain medication use, and graded attack severity were significantly less with self-administered therapy than with therapy in the clinic.21

A concern about plasma-derived products is the possibility of blood-borne infection, but this has not been confirmed by experience.22

Recombinant human C1 inhibitor

A recombinant human C1 inhibitor (Rhucin) has been studied in two randomized placebo-controlled trials. Although this product has a shorter half-life than the plasma-derived C1 inhibitors (3 vs more than 24 hours), the two are equipotent: 1 U of recombinant human C1 inhibitor is equivalent to 1 U of plasma-derived C1 inhibitor. Because the supply of recombinant human C1 inhibitor is elastic, dosing has been higher, which may provide more efficacy.23 Similar to plasma-derived C1 inhibitor products, the recombinant human C1 inhibitor resulted in more rapid symptom relief than with saline (66 vs 122 minutes) and in a shorter time to minimal symptoms (247−266 vs 1,210 minutes).24

Allergy is of concern: in one study, a healthy volunteer with undisclosed rabbit allergy experienced an allergic reaction. Patients should be screened by a skin-prick test or serum testing for specific IgE to rabbit epithelium before being prescribed recombinant human C1 inhibitor. No data are available for use during pregnancy or breastfeeding.

Ecallantide

Ecallantide (Kalbitor) is a selective inhibitor of plasma kallikrein that is given in three subcutaneous injections. Ecallantide 30 mg was found superior to placebo during acute attacks.25,26

Ecallantide is well tolerated, with the most common adverse effects being headache, nausea, fatigue, diarrhea, and local injection-site reactions. Antibodies to ecallantide can be found in patients with increasing drug exposure but do not appear to correlate with adverse events. Hypersensitivity reactions have been observed in 2% to 3% of patients receiving repeated doses. Because of anaphylaxis risk, ecallantide must be administered by a health care professional.

Icatibant

Icatibant (Firazyr) is a bradykinin receptor-2 antagonist that is given in a single subcutaneous injection. Icatibant 30 mg significantly shortened time to symptom relief and time to almost complete resolution compared with placebo.27,28 Icatibant’s main adverse effect is transient local pain, swelling, and erythema at the injection site. Icatibant can be self-administered by patients.

Fresh-frozen plasma

Fresh-frozen plasma contains C1 inhibitor and was used before the newer products became available. Several noncontrolled studies reported benefit of its use in acute attacks.29 However, its use is controversial because it also contains contact-system proteins that could provide additional substrate for the generation of bradykinin, which could exacerbate attacks in some patients.1 This may be particularly dangerous in patients presenting with laryngeal edema: in such a situation, the physician should be ready to treat a sudden exacerbation with intubation. The risk of acquiring a blood-borne pathogen is also higher than with plasma-derived C1 inhibitor.

PROPHYLACTIC MANAGEMENT

Short-term and long-term prophylaxis have important roles in preventing attacks (Table 3).

Short-term prophylaxis before an anticipated attack

Short-term prophylaxis is used for patients whose disease is generally well controlled but who anticipate exposure to a potentially exacerbating situation, such as an invasive medical, surgical, or dental procedure. (Routine dental cleanings are generally considered safe and do not require prophylaxis.)

Prophylactic treatments include:

- Plasma-derived C1 inhibitor, 500 to 1,500 U 1 hour before the provoking event

- High-dose 17-alpha alkylated (attenuated) androgens (eg, danazol [Danocrine] 200 mg orally 3 times daily) for 5 to 10 days before the provoking event

- Fresh-frozen plasma, 2 U 1 to 12 hours before the event.1

Yet even with short-term prophylaxis, on-demand treatment should be available.

Long-term prophylaxis

While many patients can be managed with on-demand treatment only, other patients (reflecting the severity of their attacks, as well as their individual needs) may benefit from a combination of on-demand treatment plus long-term prophylaxis. Several options are available (Table 3).

17-alpha alkylated androgens. Patients treated with danazol 600 mg/day were attack-free 90% of the time during a 28-day period compared with only 2.2% of the time in placebo-treated patients.30 Use of anabolic androgens, however, is limited by their adverse effects, including weight gain, virilization, menstrual irregularities, headaches, depression, dyslipidemia, liver enzyme elevation, liver adenomas, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Arterial hypertension occurs in about 25% of treated patients.

Because adverse effects are dose-dependent, treatment should be empirically titrated to find the minimal effective dose, generally recommended to be no more than 200 mg per day of danazol or the equivalent.15

Contraindications include use by women during pregnancy or lactation and by children until growth is complete.

Regular follow-up is recommended every 6 months, with monitoring of liver enzymes, lipids, complete blood counts, alpha fetoprotein, and urinalysis. Abdominal ultrasonography (every 6 months if receiving 100 mg/day or more of danazol, every 12 months if less than 100 mg/day) is advisable for early diagnosis of liver tumors.

Antifibrinolytic drugs. Tranexamic acid (Lysteda) and aminocaproic acid (Amicar) have been found to be effective in reducing the number of attacks of hereditary angioedema compared with placebo but are considered to be less reliable than androgens. These drugs have been used in patients who do not tolerate anabolic androgens, and in children and pregnant women. Tranexamic acid is given at a dose of 20 to 50 mg/kg/day divided into two or three doses per day. The therapeutic dose of aminocaproic acid is 1 g orally three to four times per day.31 Patients with a personal or family history of thromboembolic disease may be at greater risk of venous or arterial thrombosis, but this has not occurred in clinical studies.

Plasma-derived C1 inhibitors. In a 24-week crossover study in 22 patients with hereditary angioedema, Cinryze 1,000 U every 3 to 4 days reduced the rate of attacks by 50% while also reducing their severity and duration.17 An open-label extension study in 146 patients for almost 3 years documented a 90% reduction in attack frequency with no evidence of tachyphylaxis.32

New treatments are costlier

The newer on-demand and prophylactic drugs are substantially costlier than the older alternatives (androgens, antifibrinolytics, and fresh-frozen plasma); however, they have a substantially better benefit-to-risk ratio. Furthermore, the costs of care for an attack requiring emergency treatment are also high. Hereditary angioedema patients are often young, otherwise healthy, and capable of leading normal productive lives. While formal pharmacoeconomic studies of the optimal use of these newer drugs have not yet been done, it is important that the use of these drugs be well justified. Ideally, physicians who prescribe these drugs should be knowledgeable in the management of hereditary angioedema.

SPECIAL CHALLENGES IN WOMEN

Women with hereditary angioedema have more frequent attacks and generally a more severe disease course than men.12 Optimizing care for women is challenging because hormonal changes often cause the disease to flare up in menarche, pregnancy, lactation, and menopause. Women also have a higher rate of discontinuing long-term androgen therapy because of side effects, including virilization and menstrual irregularities. Spironolactone (Aldactone) 100 to 200 mg daily can be used to control hirsutism.33

Contraception

Because estrogen can trigger attacks, progesterone-only formulations, intrauterine devices, or barrier methods are recommended for contraception.33 Progesterone-only pills are preferred and improve symptoms in more than 60% of women. Etonogestrel, another alternative, is available as an implant (Implanon) or vaginal ring (Nuvaring). Intrauterine devices are generally well tolerated, and no prophylaxis is needed during placement. The progesterone-eluting intrauterine device (Mirena) could be beneficial.34

Pregnancy and lactation

Pregnancy and lactation pose particular challenges. Anabolic androgens are contraindicated during pregnancy as well as during breastfeeding because they can be passed on in breast milk. Women receiving androgen prophylaxis should understand that they can still ovulate and need contraception if they are sexually active.34 Patients on attenuated androgens who desire pregnancy should discontinue them 2 months before trying to conceive.

Changes in attack patterns can be unpredictable during pregnancy. Attacks tend to be more severe during the first trimester and more frequent during the third. Due to its safety and efficacy, plasma-derived C1 inhibitor has become the treatment of choice for on-demand or prophylactic treatment during pregnancy and lactation. Antifibrinolytics are considered only when plasma-derived C1 inhibitor is not available.31 Ecallantide and icatibant have not been studied in pregnancy. If neither plasma-derived C1 inhibitor nor antifibrinolytics are available, fresh-frozen plasma or solvent-and-detergent-treated plasma can be used.

Short-term prophylaxis should be considered before amniocentesis, chorionic villous sampling, and dilation and curettage. Delivery should take place in a facility with rapid access to plasma-derived C1 inhibitor as well as consultants in obstetrics, anesthesiology, and perinatology. Although plasma-derived C1 inhibitor should be available at all times during labor and delivery, its prophylactic use is not required unless labor and delivery are particularly traumatic, the underlying hereditary angioedema is very severe, or if forceps, vacuum delivery, or cesarian section is performed. Close monitoring is recommended for at least 72 hours after routine vaginal delivery and for 1 week after cesarian section.

CONCLUSION

The goals of hereditary angioedema treatment are to alleviate morbidity and mortality associated with the disease and to improve the patient’s quality of life. Achieving these goals requires timely diagnosis, patient education, and careful selection of therapeutic modalities that are individualized to the needs of that patient. Treatments have advanced greatly in the last 4 years, and new medications for both the acute and chronic symptoms of hereditary angioedema have shown great promise.

Acknowledgment: K.T. is funded by National Institutes of Health grant T32 AI 07469.

- Zuraw BL. Clinical practice. Hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1027–1036.

- Kaplan AP. Enzymatic pathways in the pathogenesis of hereditary angioedema: the role of C1 inhibitor therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 126:918–925.

- Davis AE. C1 inhibitor and hereditary angioneurotic edema. Annu Rev Immunol 1988; 6:595–628.

- Pappalardo E, Cicardi M, Duponchel C, et al. Frequent de novo mutations and exon deletions in the C1inhibitor gene of patients with angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000; 106:1147–1154.

- Frigas E, Park M. Idiopathic recurrent angioedema. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2006; 26:739–751.

- Wagenaar-Bos IG, Drouet C, Aygören-Pursun E, et al. Functional C1-inhibitor diagnostics in hereditary angioedema: assay evaluation and recommendations. J Immunol Methods 2008; 338:14–20.

- Bork K. Diagnosis and treatment of hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2010; 6:15.

- Zuraw BL, Bork K, Binkley KE, et al. Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor function: consensus of an international expert panel. Allergy Asthma Proc 2012; 33:S145–S156.

- Byrd JB, Adam A, Brown NJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2006; 26:725–737.

- Busse PJ. Angioedema: differential diagnosis and treatment. Allergy Asthma Proc 2011; 32(suppl 1):S3–S11.

- Prematta MJ, Kemp JG, Gibbs JG, Mende C, Rhoads C, Craig TJ. Frequency, timing, and type of prodromal symptoms associated with hereditary angioedema attacks. Allergy Asthma Proc 2009; 30:506–511.

- Bork K, Meng G, Staubach P, Hardt J. Hereditary angioedema: new findings concerning symptoms, affected organs, and course. Am J Med 2006; 119:267–274.

- Farkas H, Füst G, Fekete B, Karádi I, Varga L. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and improvement of hereditary angioneurotic oedema. Lancet 2001; 358:1695–1696.

- Bork K, Barnstedt SE. Treatment of 193 episodes of laryngeal edema with C1 inhibitor concentrate in patients with hereditary angioedema. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161:714–718.

- Cicardi M, Bork K, Caballero T, et al; HAWK (Hereditary Angioedema International Working Group). Evidence-based recommendations for the therapeutic management of angioedema owing to hereditary C1 inhibitor deficiency: consensus report of an International Working Group. Allergy 2012; 67:147–157.

- Craig TJ, Levy RJ, Wasserman RL, et al. Efficacy of human C1 esterase inhibitor concentrate compared with placebo in acute hereditary angioedema attacks. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 124:801–808.

- Zuraw BL, Busse PJ, White M, et al. Nanofiltered C1 inhibitor concentrate for treatment of hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:513–522.

- Bork K, Meng G, Staubach P, Hardt J. Treatment with C1 inhibitor concentrate in abdominal pain attacks of patients with hereditary angioedema. Transfusion 2005; 45:1774–1784.

- Kreuz W, Martinez-Saguer I, Aygören-Pürsün E, Rusicke E, Heller C, Klingebiel T. C1-inhibitor concentrate for individual replacement therapy in patients with severe hereditary angioedema refractory to danazol prophylaxis. Transfusion 2009; 49:1987–1995.

- Farkas H, Varga L, Széplaki G, Visy B, Harmat G, Bowen T. Management of hereditary angioedema in pediatric patients. Pediatrics 2007; 120:e713–e722.

- Tourangeau LM, Castaldo AJ, Davis DK, Koziol J, Christiansen SC, Zuraw BL. Safety and efficacy of physician-supervised self-managed C1 inhibitor replacement therapy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2012; 157:417–424.

- De Serres J, Gröner A, Lindner J. Safety and efficacy of pasteurized C1 inhibitor concentrate (Berinert P) in hereditary angioedema: a review. Transfus Apher Sci 2003; 29:247–254.

- Hack CE, Relan A, van Amersfoort ES, Cicardi M. Target levels of functional C1-inhibitor in hereditary angioedema. Allergy 2012; 67:123–130.

- Zuraw B, Cicardi M, Levy RJ, et al. Recombinant human C1-inhibitor for the treatment of acute angioedema attacks in patients with hereditary angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 126:821–827.e14.

- Cicardi M, Levy RJ, McNeil DL, et al. Ecallantide for the treatment of acute attacks in hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:523–531.

- Levy RJ, Lumry WR, McNeil DL, et al. EDEMA4: a phase 3, double-blind study of subcutaneous ecallantide treatment for acute attacks of hereditary angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2010; 104:523–529.

- Cicardi M, Banerji A, Bracho F, et al. Icatibant, a new bradykinin-receptor antagonist, in hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:532–541.

- Lumry WR, Li HH, Levy RJ, et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of the bradykinin B2 receptor antagonist icatibant for the treatment of acute attacks of hereditary angioedema: the FAST-3 trial. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2011; 107:529–537.

- Prematta M, Gibbs JG, Pratt EL, Stoughton TR, Craig TJ. Fresh frozen plasma for the treatment of hereditary angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2007; 98:383–388.

- Gelfand JA, Sherins RJ, Alling DW, Frank MM. Treatment of hereditary angioedema with danazol. Reversal of clinical and biochemical abnormalities. N Engl J Med 1976; 295:1444–1448.

- Zuraw BL. HAE therapies: past present and future. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2010; 6:23.

- Zuraw BL, Kalfus I. Safety and efficacy of prophylactic nanofiltered C1-inhibitor in hereditary angioedema. Am J Med 2012: Epub ahead of print.

- Caballero T, Farkas H, Bouillet L, et al; C-1-INH Deficiency Working Group. International consensus and practical guidelines on the gynecologic and obstetric management of female patients with hereditary angioedema caused by C1 inhibitor deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 129:308–320.

- Bouillet L, Longhurst H, Boccon-Gibod I, et al. Disease expression in women with hereditary angioedema. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008; 199:484.e1–e4.

Hereditary angioedema due to deficiency of C1 inhibitor is a rare autosomal dominant disease that can be life-threatening. It affects about 1 in 50,000 people,1 or about 6,000 people in the United States. There are no known differences in prevalence by ethnicity or sex. A form of hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels has also recently been identified.

Despite a growing awareness of hereditary angioedema in the medical community, repeated surveys have found an average gap of 10 years between the first appearance of symptoms and the correct diagnosis. In view of the risk of morbidity and death, recognizing this disease sooner is critical.

This article will discuss how to recognize hereditary angioedema and how to differentiate it from other forms of recurring angioedema. We will also review its acute and long-term management, with special attention to new therapies and clinical challenges.

EPISODES OF SWELLING WITHOUT HIVES

Hereditary angioedema involves recurrent episodes of nonpruritic, nonpitting, subcutaneous and submucosal edema that can affect the face, tongue, larynx, trunk, extremities, bowels, or genitals. Attacks typically follow a predictable course: swelling that increases slowly and continuously for 24 hours and then gradually subsides over the next 48 to 72 hours. Attacks that involve the oropharynx, larynx, or abdomen carry the highest risk of morbidity and death.1

The frequency and severity of attacks are highly variable and unpredictable. A few patients have no attacks, a few have two attacks per week, and most fall in between.

Hives suggests an allergic or idiopathic rather than hereditary cause and will not be discussed here in detail. A history of angioedema that was rapidly aborted by antihistamines, corticosteroids, or epinephrine also suggests an allergic rather than hereditary cause.

UNCHECKED BRADYKININ PRODUCTION

Substantial evidence indicates that hereditary angioedema results from extravasation of plasma into deeper cutaneous or mucosal compartments as a result of overproduction of the vasoactive mediator bradykinin (Figure 1).

Activated factor XII cleaves plasma prekallikrein to generate active plasma kallikrein (which, in turn, activates more factor XII).2 Once generated, plasma kallikrein cleaves high-molecular-weight kininogen, releasing bradykinin. Bradykinin binds to the B2 bradykinin receptor on endothelial cells, increasing the permeability of the endothelium.

Normally, C1 inhibitor helps control bradykinin production by inhibiting plasma kallikrein and activated factor XII. Without enough C1 inhibitor, the contact system is uninhibited and results in bradykinin being inappropriately generated.

Because the attacks of hereditary angioedema involve excessive bradykinin, they do not respond to the usual treatments for anaphylaxis and allergic angioedema (which involve mast cell degranulation), such as antihistamines, corticosteroids, and epinephrine.

TWO TYPES OF HEREDITARY ANGIOEDEMA

Figure 2 shows the evaluation of patients with suspected hereditary angioedema.

Hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency

The classic forms of hereditary angioedema (types I and II) involve loss-of-function mutations in SERPING1—the gene that encodes for C1 inhibitor—resulting in low levels of functional C1 inhibitor.3 The mutation is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern; however, in about 25% of cases, it appears to arise spontaneously,4 so a family history is not required for diagnosis.

Although C1 inhibitor deficiency is present from birth, the clinical disease most commonly presents for the first time when the patient is of school age. Half of patients have their first episode in the first decade of life, and another one-third first develop symptoms over the next 10 years.5

Clinically, types I and II are indistinguishable. Type I, accounting for 85% of cases,1 results from low production of C1 inhibitor. Laboratory studies reveal low antigenic and functional levels of C1 inhibitor.

In type II, the mutant C1 inhibitor protein is present but dysfunctional and unable to inhibit target proteases. On laboratory testing, the functional level of C1 inhibitor is low but its antigenic level is normal (Table 1). Function can be tested by either chromogenic assay or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; the former is preferred because it is more sensitive.6

Because C1 inhibitor deficiency results in chronic activation of the complement system, patients with type I or II disease usually have low C4 levels regardless of disease activity, making measuring C4 the most economical screening test. When suspicion for hereditary angioedema is high, based on the presentation and family and clinical history, measuring antigenic and functional C1 inhibitor levels and C4 simultaneously is more efficient.

Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels

Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels is also inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. It is often estrogen-sensitive, making it more severe in women. Symptoms tend to develop slightly later in life than in type I or II disease.7

Angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels has been associated with factor XII mutations in a minority of cases, but most patients do not have a specific laboratory abnormality. Because there is no specific laboratory profile, the diagnosis is based on clinical criteria. Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels should be considered in patients who have recurrent angioedema, normal C4, normal antigenic and functional C1 inhibitor levels, a lack of response to high-dose antihistamines, and either a family history of angioedema without hives or a known factor XII mutation.7 However, other forms of angioedema (allergic, drug-induced, and idiopathic) should also be considered, as C4 and C1 inhibitor levels are normal in these forms as well.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS: OTHER TYPES OF ANGIOEDEMA

Acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency

Symptoms of acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency resemble those of hereditary angioedema but typically do not emerge until the fourth decade of life or later, and patients have no family history of the condition. It is often associated with other diseases, most commonly B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, which cause uncontrolled complement activation and consumption of C1 inhibitor.

In some patients, autoantibodies to C1 inhibitor develop, greatly reducing its effectiveness and resulting in enhanced consumption. The autoantibody is often associated with a monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance. The presence of a C1 inhibitor autoantibody does not preclude the presence of an underlying disorder, and vice versa.

Laboratory studies reveal low C4, low C1-inhibitor antigenic and functional levels, and usually a low C1q level owing to consumption of complement. Autoantibodies to C1 inhibitor can be detected by laboratory testing.

Because of the association with autoimmune disease and malignant disorders (especially B-cell malignancy), a patient diagnosed with acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency should be further evaluated for underlying conditions.

Allergic angioedema

Allergic angioedema results from preformed antigen-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies that stimulate mast cells to degranulate when patients are exposed to a particular allergen—most commonly food, insect venom, latex, or drugs. IgE-mediated histamine release causes swelling, as histamine is a potent vasodilator.

Symptoms often begin within 2 hours of exposure to the allergen and generally include concurrent urticaria and swelling that last less than 24 hours. Unlike in hereditary angioedema, the swelling responds to antihistamines and corticosteroids. When very severe, these symptoms may also be accompanied by bronchoconstriction and gastrointestinal symptoms, especially if the allergen is ingested.

Histamine-mediated angioedema may also be associated with exercise as part of a syndrome called exercise-induced anaphylaxis or angioedema.

Drug-induced angioedema

Drug-induced angioedema is typically associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Angioedema associated with ACE inhibitors is estimated to affect 0.1% to 6% of patients taking these medications, with African Americans being at significantly higher risk. Although 25% of affected patients develop symptoms of angioedema within the first month of taking the drugs, some tolerate them for as long as 10 years before the first episode.9 The swelling is not allergic or histamine-related. ACE normally degrades bradykinin; therefore, inhibiting ACE leads to accumulation of bradykinin. Because all ACE inhibitors have this effect, this class of drug should be discontinued in any patient who develops isolated angioedema.

NSAID-induced angioedema is often accompanied by other symptoms, including urticaria, rhinitis, cough, hoarseness, or breathlessness.10 The mechanism of NSAID-induced angioedema involves cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 (and to a lesser extent COX-2) inhibition. All NSAIDs (and aspirin) should be avoided in patients with recurrent angioedema. Specific COX-2 inhibitors, while theoretically capable of causing angioedema by the same mechanism, are generally well tolerated in patients who have had COX-1 inhibitor reactions.

Idiopathic angioedema

If no clear cause of recurrent angioedema (at least three episodes in a year) can be found, it is labeled idiopathic.11 Some patients with idiopathic angioedema fail to benefit from high doses of antihistamines, suggesting that the cause is bradykinin-mediated.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF HEREDITARY ANGIOEDEMA

Attacks may start at one site and progress to involve additional sites.

Prodromal symptoms may begin up to several days before an attack and include tingling, warmth, burning, or itching at the affected site; increased fatigue or malaise; nausea, abdominal distention, or gassiness; or increased hunger, particularly before an abdominal attack.5 The most characteristic prodromal symptom is erythema marginatum—a raised, serpiginous, nonpruritic rash on the trunk, arms, and legs but often sparing the face.

Abdominal attacks are easily confused with acute abdomen

Almost half of attacks involve the abdomen, and almost all patients with type I or II disease experience at least one such attack.12 Symptoms can include severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Abdominal attacks account for many emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and surgical procedures for acute abdomen; about one-third of patients with undiagnosed hereditary angioedema undergo an unnecessary surgery during an abdominal attack. Angioedema of the gastrointestinal tract can result in enough plasma extravasation and vasodilation to cause hypovolemic shock.

Eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection may alleviate abdominal attacks.13

Attacks of the extremities can be painful and disabling

Attacks of the extremities affect 96% of patients12 and can be very disfiguring and disabling. Driving or using the phone is often difficult when the hands are affected. When feet are involved, walking and standing become painful. While these symptoms rarely result in a lengthy hospitalization, they interfere with work and school and require immediate medical attention because they can progress to other parts of the body.

Laryngeal attacks are life-threatening

About half of patients with hereditary angioedema have an attack of laryngeal edema at some point in their lives.12 If not effectively managed, laryngeal angioedema can progress to asphyxiation. A survey of family history in 58 patients with hereditary angioedema suggested a 40% incidence of asphyxiation in untreated laryngeal attacks, and 25% to 30% of patients are estimated to have died of laryngeal edema before effective treatment became available.14

Symptoms of a laryngeal attack include change in voice, hoarseness, trouble swallowing, shortness of breath, and wheezing. Physicians must recognize these symptoms quickly and give effective treatment early in the attack to prevent morbidity and death.

Establishing an airway can be life-saving in the absence of effective therapy, but extensive swelling of the upper airway can make intubation extremely difficult.

Genitourinary attacks also occur

Attacks involving the scrotum and labia have been reported in up to two-thirds of patients with hereditary angioedema at some point in their lives. Attacks involving the bladder and kidneys have also been reported but are less common, affecting about 5% of patients.12 Genitourinary attacks may be triggered by local trauma, such as horseback riding or sexual intercourse, although no trigger may be evident.

MANAGING ACUTE ATTACKS

The goals of treatment are to alleviate acute exacerbations with on-demand treatment and to reduce the number of attacks with prophylaxis. Therapy should be individualized to each patient’s needs. Treatments have advanced greatly in the last several years, and new medications for treating acute attacks and preventing attacks have shown great promise (Figure 3, Table 2).

Patients tend to have recurrent symptoms interspersed with periods of health, suggesting that attacks ought to have identifiable triggers, although in most, no trigger is evident. The most commonly identified are local trauma (including medical and dental procedures), emotional stress, and acute infection. Disease severity may be worsened by menstruation, estrogen-containing oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, ACE inhibitors, and NSAIDs.

It is critical that attacks be treated with an effective medication as soon as possible. Consensus guidelines state that all patients with hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency, even if they are still asymptomatic, should have access to at least one of the drugs approved for on-demand treatment.15 The guidelines further state that whenever possible, “patients should have the on-demand medicine to treat acute attacks at home and should be trained to self-administer these medicines.”15

Plasma-derived C1 inhibitors

Several plasma-derived C1 inhibitors are available (Cinryze, Berinert, Cetor). They are prepared from fractionated plasma obtained from donors, then pasteurized and nanofiltered.

Berinert and Cinryze were each found to be superior to placebo in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials: attacks usually resolved 30 to 60 minutes after intravenous injection.16,17 Berinert 20 U/kg is associated with the onset of symptom relief as early as half an hour after administration, compared with 1.5 hours with placebo. Early use (at the onset of symptoms) of a plasma-derived C1 inhibitor in a low dose (500 U) can also be effective.18,19 Efficacy appears to be consistent at all sites of attack involvement, including laryngeal edema. Safety and efficacy have been demonstrated during pregnancy and lactation and in young children and babies.20

Plasma-derived C1 inhibitors can be self-administered. The safety and efficacy of self-administration (under physician supervision) were demonstrated in a study of Cinryze and Cetor, in which attack duration, pain medication use, and graded attack severity were significantly less with self-administered therapy than with therapy in the clinic.21

A concern about plasma-derived products is the possibility of blood-borne infection, but this has not been confirmed by experience.22

Recombinant human C1 inhibitor

A recombinant human C1 inhibitor (Rhucin) has been studied in two randomized placebo-controlled trials. Although this product has a shorter half-life than the plasma-derived C1 inhibitors (3 vs more than 24 hours), the two are equipotent: 1 U of recombinant human C1 inhibitor is equivalent to 1 U of plasma-derived C1 inhibitor. Because the supply of recombinant human C1 inhibitor is elastic, dosing has been higher, which may provide more efficacy.23 Similar to plasma-derived C1 inhibitor products, the recombinant human C1 inhibitor resulted in more rapid symptom relief than with saline (66 vs 122 minutes) and in a shorter time to minimal symptoms (247−266 vs 1,210 minutes).24

Allergy is of concern: in one study, a healthy volunteer with undisclosed rabbit allergy experienced an allergic reaction. Patients should be screened by a skin-prick test or serum testing for specific IgE to rabbit epithelium before being prescribed recombinant human C1 inhibitor. No data are available for use during pregnancy or breastfeeding.

Ecallantide

Ecallantide (Kalbitor) is a selective inhibitor of plasma kallikrein that is given in three subcutaneous injections. Ecallantide 30 mg was found superior to placebo during acute attacks.25,26

Ecallantide is well tolerated, with the most common adverse effects being headache, nausea, fatigue, diarrhea, and local injection-site reactions. Antibodies to ecallantide can be found in patients with increasing drug exposure but do not appear to correlate with adverse events. Hypersensitivity reactions have been observed in 2% to 3% of patients receiving repeated doses. Because of anaphylaxis risk, ecallantide must be administered by a health care professional.

Icatibant

Icatibant (Firazyr) is a bradykinin receptor-2 antagonist that is given in a single subcutaneous injection. Icatibant 30 mg significantly shortened time to symptom relief and time to almost complete resolution compared with placebo.27,28 Icatibant’s main adverse effect is transient local pain, swelling, and erythema at the injection site. Icatibant can be self-administered by patients.

Fresh-frozen plasma

Fresh-frozen plasma contains C1 inhibitor and was used before the newer products became available. Several noncontrolled studies reported benefit of its use in acute attacks.29 However, its use is controversial because it also contains contact-system proteins that could provide additional substrate for the generation of bradykinin, which could exacerbate attacks in some patients.1 This may be particularly dangerous in patients presenting with laryngeal edema: in such a situation, the physician should be ready to treat a sudden exacerbation with intubation. The risk of acquiring a blood-borne pathogen is also higher than with plasma-derived C1 inhibitor.

PROPHYLACTIC MANAGEMENT

Short-term and long-term prophylaxis have important roles in preventing attacks (Table 3).

Short-term prophylaxis before an anticipated attack

Short-term prophylaxis is used for patients whose disease is generally well controlled but who anticipate exposure to a potentially exacerbating situation, such as an invasive medical, surgical, or dental procedure. (Routine dental cleanings are generally considered safe and do not require prophylaxis.)

Prophylactic treatments include:

- Plasma-derived C1 inhibitor, 500 to 1,500 U 1 hour before the provoking event

- High-dose 17-alpha alkylated (attenuated) androgens (eg, danazol [Danocrine] 200 mg orally 3 times daily) for 5 to 10 days before the provoking event

- Fresh-frozen plasma, 2 U 1 to 12 hours before the event.1

Yet even with short-term prophylaxis, on-demand treatment should be available.

Long-term prophylaxis

While many patients can be managed with on-demand treatment only, other patients (reflecting the severity of their attacks, as well as their individual needs) may benefit from a combination of on-demand treatment plus long-term prophylaxis. Several options are available (Table 3).

17-alpha alkylated androgens. Patients treated with danazol 600 mg/day were attack-free 90% of the time during a 28-day period compared with only 2.2% of the time in placebo-treated patients.30 Use of anabolic androgens, however, is limited by their adverse effects, including weight gain, virilization, menstrual irregularities, headaches, depression, dyslipidemia, liver enzyme elevation, liver adenomas, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Arterial hypertension occurs in about 25% of treated patients.

Because adverse effects are dose-dependent, treatment should be empirically titrated to find the minimal effective dose, generally recommended to be no more than 200 mg per day of danazol or the equivalent.15

Contraindications include use by women during pregnancy or lactation and by children until growth is complete.

Regular follow-up is recommended every 6 months, with monitoring of liver enzymes, lipids, complete blood counts, alpha fetoprotein, and urinalysis. Abdominal ultrasonography (every 6 months if receiving 100 mg/day or more of danazol, every 12 months if less than 100 mg/day) is advisable for early diagnosis of liver tumors.

Antifibrinolytic drugs. Tranexamic acid (Lysteda) and aminocaproic acid (Amicar) have been found to be effective in reducing the number of attacks of hereditary angioedema compared with placebo but are considered to be less reliable than androgens. These drugs have been used in patients who do not tolerate anabolic androgens, and in children and pregnant women. Tranexamic acid is given at a dose of 20 to 50 mg/kg/day divided into two or three doses per day. The therapeutic dose of aminocaproic acid is 1 g orally three to four times per day.31 Patients with a personal or family history of thromboembolic disease may be at greater risk of venous or arterial thrombosis, but this has not occurred in clinical studies.

Plasma-derived C1 inhibitors. In a 24-week crossover study in 22 patients with hereditary angioedema, Cinryze 1,000 U every 3 to 4 days reduced the rate of attacks by 50% while also reducing their severity and duration.17 An open-label extension study in 146 patients for almost 3 years documented a 90% reduction in attack frequency with no evidence of tachyphylaxis.32

New treatments are costlier

The newer on-demand and prophylactic drugs are substantially costlier than the older alternatives (androgens, antifibrinolytics, and fresh-frozen plasma); however, they have a substantially better benefit-to-risk ratio. Furthermore, the costs of care for an attack requiring emergency treatment are also high. Hereditary angioedema patients are often young, otherwise healthy, and capable of leading normal productive lives. While formal pharmacoeconomic studies of the optimal use of these newer drugs have not yet been done, it is important that the use of these drugs be well justified. Ideally, physicians who prescribe these drugs should be knowledgeable in the management of hereditary angioedema.

SPECIAL CHALLENGES IN WOMEN

Women with hereditary angioedema have more frequent attacks and generally a more severe disease course than men.12 Optimizing care for women is challenging because hormonal changes often cause the disease to flare up in menarche, pregnancy, lactation, and menopause. Women also have a higher rate of discontinuing long-term androgen therapy because of side effects, including virilization and menstrual irregularities. Spironolactone (Aldactone) 100 to 200 mg daily can be used to control hirsutism.33

Contraception

Because estrogen can trigger attacks, progesterone-only formulations, intrauterine devices, or barrier methods are recommended for contraception.33 Progesterone-only pills are preferred and improve symptoms in more than 60% of women. Etonogestrel, another alternative, is available as an implant (Implanon) or vaginal ring (Nuvaring). Intrauterine devices are generally well tolerated, and no prophylaxis is needed during placement. The progesterone-eluting intrauterine device (Mirena) could be beneficial.34

Pregnancy and lactation

Pregnancy and lactation pose particular challenges. Anabolic androgens are contraindicated during pregnancy as well as during breastfeeding because they can be passed on in breast milk. Women receiving androgen prophylaxis should understand that they can still ovulate and need contraception if they are sexually active.34 Patients on attenuated androgens who desire pregnancy should discontinue them 2 months before trying to conceive.

Changes in attack patterns can be unpredictable during pregnancy. Attacks tend to be more severe during the first trimester and more frequent during the third. Due to its safety and efficacy, plasma-derived C1 inhibitor has become the treatment of choice for on-demand or prophylactic treatment during pregnancy and lactation. Antifibrinolytics are considered only when plasma-derived C1 inhibitor is not available.31 Ecallantide and icatibant have not been studied in pregnancy. If neither plasma-derived C1 inhibitor nor antifibrinolytics are available, fresh-frozen plasma or solvent-and-detergent-treated plasma can be used.

Short-term prophylaxis should be considered before amniocentesis, chorionic villous sampling, and dilation and curettage. Delivery should take place in a facility with rapid access to plasma-derived C1 inhibitor as well as consultants in obstetrics, anesthesiology, and perinatology. Although plasma-derived C1 inhibitor should be available at all times during labor and delivery, its prophylactic use is not required unless labor and delivery are particularly traumatic, the underlying hereditary angioedema is very severe, or if forceps, vacuum delivery, or cesarian section is performed. Close monitoring is recommended for at least 72 hours after routine vaginal delivery and for 1 week after cesarian section.

CONCLUSION

The goals of hereditary angioedema treatment are to alleviate morbidity and mortality associated with the disease and to improve the patient’s quality of life. Achieving these goals requires timely diagnosis, patient education, and careful selection of therapeutic modalities that are individualized to the needs of that patient. Treatments have advanced greatly in the last 4 years, and new medications for both the acute and chronic symptoms of hereditary angioedema have shown great promise.

Acknowledgment: K.T. is funded by National Institutes of Health grant T32 AI 07469.

Hereditary angioedema due to deficiency of C1 inhibitor is a rare autosomal dominant disease that can be life-threatening. It affects about 1 in 50,000 people,1 or about 6,000 people in the United States. There are no known differences in prevalence by ethnicity or sex. A form of hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels has also recently been identified.

Despite a growing awareness of hereditary angioedema in the medical community, repeated surveys have found an average gap of 10 years between the first appearance of symptoms and the correct diagnosis. In view of the risk of morbidity and death, recognizing this disease sooner is critical.

This article will discuss how to recognize hereditary angioedema and how to differentiate it from other forms of recurring angioedema. We will also review its acute and long-term management, with special attention to new therapies and clinical challenges.

EPISODES OF SWELLING WITHOUT HIVES

Hereditary angioedema involves recurrent episodes of nonpruritic, nonpitting, subcutaneous and submucosal edema that can affect the face, tongue, larynx, trunk, extremities, bowels, or genitals. Attacks typically follow a predictable course: swelling that increases slowly and continuously for 24 hours and then gradually subsides over the next 48 to 72 hours. Attacks that involve the oropharynx, larynx, or abdomen carry the highest risk of morbidity and death.1

The frequency and severity of attacks are highly variable and unpredictable. A few patients have no attacks, a few have two attacks per week, and most fall in between.

Hives suggests an allergic or idiopathic rather than hereditary cause and will not be discussed here in detail. A history of angioedema that was rapidly aborted by antihistamines, corticosteroids, or epinephrine also suggests an allergic rather than hereditary cause.

UNCHECKED BRADYKININ PRODUCTION

Substantial evidence indicates that hereditary angioedema results from extravasation of plasma into deeper cutaneous or mucosal compartments as a result of overproduction of the vasoactive mediator bradykinin (Figure 1).

Activated factor XII cleaves plasma prekallikrein to generate active plasma kallikrein (which, in turn, activates more factor XII).2 Once generated, plasma kallikrein cleaves high-molecular-weight kininogen, releasing bradykinin. Bradykinin binds to the B2 bradykinin receptor on endothelial cells, increasing the permeability of the endothelium.

Normally, C1 inhibitor helps control bradykinin production by inhibiting plasma kallikrein and activated factor XII. Without enough C1 inhibitor, the contact system is uninhibited and results in bradykinin being inappropriately generated.

Because the attacks of hereditary angioedema involve excessive bradykinin, they do not respond to the usual treatments for anaphylaxis and allergic angioedema (which involve mast cell degranulation), such as antihistamines, corticosteroids, and epinephrine.

TWO TYPES OF HEREDITARY ANGIOEDEMA

Figure 2 shows the evaluation of patients with suspected hereditary angioedema.

Hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency

The classic forms of hereditary angioedema (types I and II) involve loss-of-function mutations in SERPING1—the gene that encodes for C1 inhibitor—resulting in low levels of functional C1 inhibitor.3 The mutation is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern; however, in about 25% of cases, it appears to arise spontaneously,4 so a family history is not required for diagnosis.

Although C1 inhibitor deficiency is present from birth, the clinical disease most commonly presents for the first time when the patient is of school age. Half of patients have their first episode in the first decade of life, and another one-third first develop symptoms over the next 10 years.5

Clinically, types I and II are indistinguishable. Type I, accounting for 85% of cases,1 results from low production of C1 inhibitor. Laboratory studies reveal low antigenic and functional levels of C1 inhibitor.

In type II, the mutant C1 inhibitor protein is present but dysfunctional and unable to inhibit target proteases. On laboratory testing, the functional level of C1 inhibitor is low but its antigenic level is normal (Table 1). Function can be tested by either chromogenic assay or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; the former is preferred because it is more sensitive.6

Because C1 inhibitor deficiency results in chronic activation of the complement system, patients with type I or II disease usually have low C4 levels regardless of disease activity, making measuring C4 the most economical screening test. When suspicion for hereditary angioedema is high, based on the presentation and family and clinical history, measuring antigenic and functional C1 inhibitor levels and C4 simultaneously is more efficient.

Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels

Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels is also inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. It is often estrogen-sensitive, making it more severe in women. Symptoms tend to develop slightly later in life than in type I or II disease.7

Angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels has been associated with factor XII mutations in a minority of cases, but most patients do not have a specific laboratory abnormality. Because there is no specific laboratory profile, the diagnosis is based on clinical criteria. Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels should be considered in patients who have recurrent angioedema, normal C4, normal antigenic and functional C1 inhibitor levels, a lack of response to high-dose antihistamines, and either a family history of angioedema without hives or a known factor XII mutation.7 However, other forms of angioedema (allergic, drug-induced, and idiopathic) should also be considered, as C4 and C1 inhibitor levels are normal in these forms as well.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS: OTHER TYPES OF ANGIOEDEMA

Acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency

Symptoms of acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency resemble those of hereditary angioedema but typically do not emerge until the fourth decade of life or later, and patients have no family history of the condition. It is often associated with other diseases, most commonly B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, which cause uncontrolled complement activation and consumption of C1 inhibitor.

In some patients, autoantibodies to C1 inhibitor develop, greatly reducing its effectiveness and resulting in enhanced consumption. The autoantibody is often associated with a monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance. The presence of a C1 inhibitor autoantibody does not preclude the presence of an underlying disorder, and vice versa.

Laboratory studies reveal low C4, low C1-inhibitor antigenic and functional levels, and usually a low C1q level owing to consumption of complement. Autoantibodies to C1 inhibitor can be detected by laboratory testing.

Because of the association with autoimmune disease and malignant disorders (especially B-cell malignancy), a patient diagnosed with acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency should be further evaluated for underlying conditions.

Allergic angioedema

Allergic angioedema results from preformed antigen-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies that stimulate mast cells to degranulate when patients are exposed to a particular allergen—most commonly food, insect venom, latex, or drugs. IgE-mediated histamine release causes swelling, as histamine is a potent vasodilator.

Symptoms often begin within 2 hours of exposure to the allergen and generally include concurrent urticaria and swelling that last less than 24 hours. Unlike in hereditary angioedema, the swelling responds to antihistamines and corticosteroids. When very severe, these symptoms may also be accompanied by bronchoconstriction and gastrointestinal symptoms, especially if the allergen is ingested.

Histamine-mediated angioedema may also be associated with exercise as part of a syndrome called exercise-induced anaphylaxis or angioedema.

Drug-induced angioedema

Drug-induced angioedema is typically associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Angioedema associated with ACE inhibitors is estimated to affect 0.1% to 6% of patients taking these medications, with African Americans being at significantly higher risk. Although 25% of affected patients develop symptoms of angioedema within the first month of taking the drugs, some tolerate them for as long as 10 years before the first episode.9 The swelling is not allergic or histamine-related. ACE normally degrades bradykinin; therefore, inhibiting ACE leads to accumulation of bradykinin. Because all ACE inhibitors have this effect, this class of drug should be discontinued in any patient who develops isolated angioedema.

NSAID-induced angioedema is often accompanied by other symptoms, including urticaria, rhinitis, cough, hoarseness, or breathlessness.10 The mechanism of NSAID-induced angioedema involves cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 (and to a lesser extent COX-2) inhibition. All NSAIDs (and aspirin) should be avoided in patients with recurrent angioedema. Specific COX-2 inhibitors, while theoretically capable of causing angioedema by the same mechanism, are generally well tolerated in patients who have had COX-1 inhibitor reactions.

Idiopathic angioedema

If no clear cause of recurrent angioedema (at least three episodes in a year) can be found, it is labeled idiopathic.11 Some patients with idiopathic angioedema fail to benefit from high doses of antihistamines, suggesting that the cause is bradykinin-mediated.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF HEREDITARY ANGIOEDEMA

Attacks may start at one site and progress to involve additional sites.

Prodromal symptoms may begin up to several days before an attack and include tingling, warmth, burning, or itching at the affected site; increased fatigue or malaise; nausea, abdominal distention, or gassiness; or increased hunger, particularly before an abdominal attack.5 The most characteristic prodromal symptom is erythema marginatum—a raised, serpiginous, nonpruritic rash on the trunk, arms, and legs but often sparing the face.

Abdominal attacks are easily confused with acute abdomen

Almost half of attacks involve the abdomen, and almost all patients with type I or II disease experience at least one such attack.12 Symptoms can include severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Abdominal attacks account for many emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and surgical procedures for acute abdomen; about one-third of patients with undiagnosed hereditary angioedema undergo an unnecessary surgery during an abdominal attack. Angioedema of the gastrointestinal tract can result in enough plasma extravasation and vasodilation to cause hypovolemic shock.

Eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection may alleviate abdominal attacks.13

Attacks of the extremities can be painful and disabling

Attacks of the extremities affect 96% of patients12 and can be very disfiguring and disabling. Driving or using the phone is often difficult when the hands are affected. When feet are involved, walking and standing become painful. While these symptoms rarely result in a lengthy hospitalization, they interfere with work and school and require immediate medical attention because they can progress to other parts of the body.

Laryngeal attacks are life-threatening

About half of patients with hereditary angioedema have an attack of laryngeal edema at some point in their lives.12 If not effectively managed, laryngeal angioedema can progress to asphyxiation. A survey of family history in 58 patients with hereditary angioedema suggested a 40% incidence of asphyxiation in untreated laryngeal attacks, and 25% to 30% of patients are estimated to have died of laryngeal edema before effective treatment became available.14

Symptoms of a laryngeal attack include change in voice, hoarseness, trouble swallowing, shortness of breath, and wheezing. Physicians must recognize these symptoms quickly and give effective treatment early in the attack to prevent morbidity and death.

Establishing an airway can be life-saving in the absence of effective therapy, but extensive swelling of the upper airway can make intubation extremely difficult.

Genitourinary attacks also occur

Attacks involving the scrotum and labia have been reported in up to two-thirds of patients with hereditary angioedema at some point in their lives. Attacks involving the bladder and kidneys have also been reported but are less common, affecting about 5% of patients.12 Genitourinary attacks may be triggered by local trauma, such as horseback riding or sexual intercourse, although no trigger may be evident.

MANAGING ACUTE ATTACKS

The goals of treatment are to alleviate acute exacerbations with on-demand treatment and to reduce the number of attacks with prophylaxis. Therapy should be individualized to each patient’s needs. Treatments have advanced greatly in the last several years, and new medications for treating acute attacks and preventing attacks have shown great promise (Figure 3, Table 2).

Patients tend to have recurrent symptoms interspersed with periods of health, suggesting that attacks ought to have identifiable triggers, although in most, no trigger is evident. The most commonly identified are local trauma (including medical and dental procedures), emotional stress, and acute infection. Disease severity may be worsened by menstruation, estrogen-containing oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, ACE inhibitors, and NSAIDs.

It is critical that attacks be treated with an effective medication as soon as possible. Consensus guidelines state that all patients with hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency, even if they are still asymptomatic, should have access to at least one of the drugs approved for on-demand treatment.15 The guidelines further state that whenever possible, “patients should have the on-demand medicine to treat acute attacks at home and should be trained to self-administer these medicines.”15

Plasma-derived C1 inhibitors

Several plasma-derived C1 inhibitors are available (Cinryze, Berinert, Cetor). They are prepared from fractionated plasma obtained from donors, then pasteurized and nanofiltered.

Berinert and Cinryze were each found to be superior to placebo in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials: attacks usually resolved 30 to 60 minutes after intravenous injection.16,17 Berinert 20 U/kg is associated with the onset of symptom relief as early as half an hour after administration, compared with 1.5 hours with placebo. Early use (at the onset of symptoms) of a plasma-derived C1 inhibitor in a low dose (500 U) can also be effective.18,19 Efficacy appears to be consistent at all sites of attack involvement, including laryngeal edema. Safety and efficacy have been demonstrated during pregnancy and lactation and in young children and babies.20

Plasma-derived C1 inhibitors can be self-administered. The safety and efficacy of self-administration (under physician supervision) were demonstrated in a study of Cinryze and Cetor, in which attack duration, pain medication use, and graded attack severity were significantly less with self-administered therapy than with therapy in the clinic.21

A concern about plasma-derived products is the possibility of blood-borne infection, but this has not been confirmed by experience.22

Recombinant human C1 inhibitor

A recombinant human C1 inhibitor (Rhucin) has been studied in two randomized placebo-controlled trials. Although this product has a shorter half-life than the plasma-derived C1 inhibitors (3 vs more than 24 hours), the two are equipotent: 1 U of recombinant human C1 inhibitor is equivalent to 1 U of plasma-derived C1 inhibitor. Because the supply of recombinant human C1 inhibitor is elastic, dosing has been higher, which may provide more efficacy.23 Similar to plasma-derived C1 inhibitor products, the recombinant human C1 inhibitor resulted in more rapid symptom relief than with saline (66 vs 122 minutes) and in a shorter time to minimal symptoms (247−266 vs 1,210 minutes).24

Allergy is of concern: in one study, a healthy volunteer with undisclosed rabbit allergy experienced an allergic reaction. Patients should be screened by a skin-prick test or serum testing for specific IgE to rabbit epithelium before being prescribed recombinant human C1 inhibitor. No data are available for use during pregnancy or breastfeeding.

Ecallantide

Ecallantide (Kalbitor) is a selective inhibitor of plasma kallikrein that is given in three subcutaneous injections. Ecallantide 30 mg was found superior to placebo during acute attacks.25,26

Ecallantide is well tolerated, with the most common adverse effects being headache, nausea, fatigue, diarrhea, and local injection-site reactions. Antibodies to ecallantide can be found in patients with increasing drug exposure but do not appear to correlate with adverse events. Hypersensitivity reactions have been observed in 2% to 3% of patients receiving repeated doses. Because of anaphylaxis risk, ecallantide must be administered by a health care professional.

Icatibant

Icatibant (Firazyr) is a bradykinin receptor-2 antagonist that is given in a single subcutaneous injection. Icatibant 30 mg significantly shortened time to symptom relief and time to almost complete resolution compared with placebo.27,28 Icatibant’s main adverse effect is transient local pain, swelling, and erythema at the injection site. Icatibant can be self-administered by patients.

Fresh-frozen plasma

Fresh-frozen plasma contains C1 inhibitor and was used before the newer products became available. Several noncontrolled studies reported benefit of its use in acute attacks.29 However, its use is controversial because it also contains contact-system proteins that could provide additional substrate for the generation of bradykinin, which could exacerbate attacks in some patients.1 This may be particularly dangerous in patients presenting with laryngeal edema: in such a situation, the physician should be ready to treat a sudden exacerbation with intubation. The risk of acquiring a blood-borne pathogen is also higher than with plasma-derived C1 inhibitor.

PROPHYLACTIC MANAGEMENT

Short-term and long-term prophylaxis have important roles in preventing attacks (Table 3).

Short-term prophylaxis before an anticipated attack

Short-term prophylaxis is used for patients whose disease is generally well controlled but who anticipate exposure to a potentially exacerbating situation, such as an invasive medical, surgical, or dental procedure. (Routine dental cleanings are generally considered safe and do not require prophylaxis.)

Prophylactic treatments include:

- Plasma-derived C1 inhibitor, 500 to 1,500 U 1 hour before the provoking event

- High-dose 17-alpha alkylated (attenuated) androgens (eg, danazol [Danocrine] 200 mg orally 3 times daily) for 5 to 10 days before the provoking event

- Fresh-frozen plasma, 2 U 1 to 12 hours before the event.1

Yet even with short-term prophylaxis, on-demand treatment should be available.

Long-term prophylaxis

While many patients can be managed with on-demand treatment only, other patients (reflecting the severity of their attacks, as well as their individual needs) may benefit from a combination of on-demand treatment plus long-term prophylaxis. Several options are available (Table 3).

17-alpha alkylated androgens. Patients treated with danazol 600 mg/day were attack-free 90% of the time during a 28-day period compared with only 2.2% of the time in placebo-treated patients.30 Use of anabolic androgens, however, is limited by their adverse effects, including weight gain, virilization, menstrual irregularities, headaches, depression, dyslipidemia, liver enzyme elevation, liver adenomas, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Arterial hypertension occurs in about 25% of treated patients.

Because adverse effects are dose-dependent, treatment should be empirically titrated to find the minimal effective dose, generally recommended to be no more than 200 mg per day of danazol or the equivalent.15

Contraindications include use by women during pregnancy or lactation and by children until growth is complete.

Regular follow-up is recommended every 6 months, with monitoring of liver enzymes, lipids, complete blood counts, alpha fetoprotein, and urinalysis. Abdominal ultrasonography (every 6 months if receiving 100 mg/day or more of danazol, every 12 months if less than 100 mg/day) is advisable for early diagnosis of liver tumors.