User login

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a chronic neuropsychiatric disorder occurring in early childhood or adolescence that’s characterized by multiple motor and vocal tics that are usually preceded by premonitory urges.1,2 Usually, the tics are repetitive, sudden, stereotypical, non-rhythmic movements and/or vocalizations.3,4 Individuals with TS and other tic disorders often experience impulsivity, aggression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and various mood and anxiety disorders.3 Psychosocial issues may include having low self-esteem, increased family conflict, and poor social skills. Males are affected 3 to 5 times more often than females.3

There is no definitive treatment for TS. Commonly used interventions are pharmacotherapy and/or behavioral therapy, which includes supportive psychotherapy, habit reversal training, exposure with response prevention, relaxation therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and self-monitoring. Pharmacotherapy for TS and other tic disorders consists mainly of antipsychotics such as haloperidol, pimozide, and aripiprazole, and alpha-2 agonists (guanfacine and clonidine).4,8-10 Unfortunately, not all children respond to these medications, and these agents are associated with multiple adverse effects.11 Therefore, there is a need for additional treatment options for patients with TS and other tic disorders, especially those who are not helped by conventional treatments.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a non-invasive therapeutic technique in which high-intensity magnetic impulses are delivered through an electromagnetic coil placed on the patient’s scalp to stimulate cortical neurons. The effect is determined by various parameters, including the intensity, frequency, pulse number, duration, coil location, and type of coil.3,8

rTMS is FDA-approved for treating depression, and has been used to treat anxiety disorders, Parkinson’s disease, chronic pain syndromes, and dystonia.12,13 Researchers have begun to evaluate the usefulness of rTMS for patients with TS or other tic disorders. In this article, we review the findings of 11 studies—9 clinical trials and 2 case studies—that evaluated rTMS as a treatment option for patients with tic disorders.

A proposed mechanism of action

TS is believed to be caused by multiple factors, including neurotransmitter imbalances and genetic, environmental, and psychosocial factors.14 Evidence strongly suggests the involvement of the motor cortex, basal ganglia, and reticular activating system in the expression of TS.2,15-17

Researchers have consistently identified networks of regions in the brain, including the supplementary motor area (SMA), that are active in the seconds before tics occur in patients with these disorders.6,18-22 The SMA modulates the way information is channeled between motor circuits, the limbic system, and the cognitive processes.3,23-26 The SMA can be used as a target for focal brain stimulation to modulate activity in those circuits and improve symptoms in resistant patients. Recent rTMS studies that targeted the SMA have found that stimulation to this area may be an effective way to treat TS.19,20,23,27

Continue to: rTMS for tics: Mixed evidence

rTMS for tics: Mixed evidence

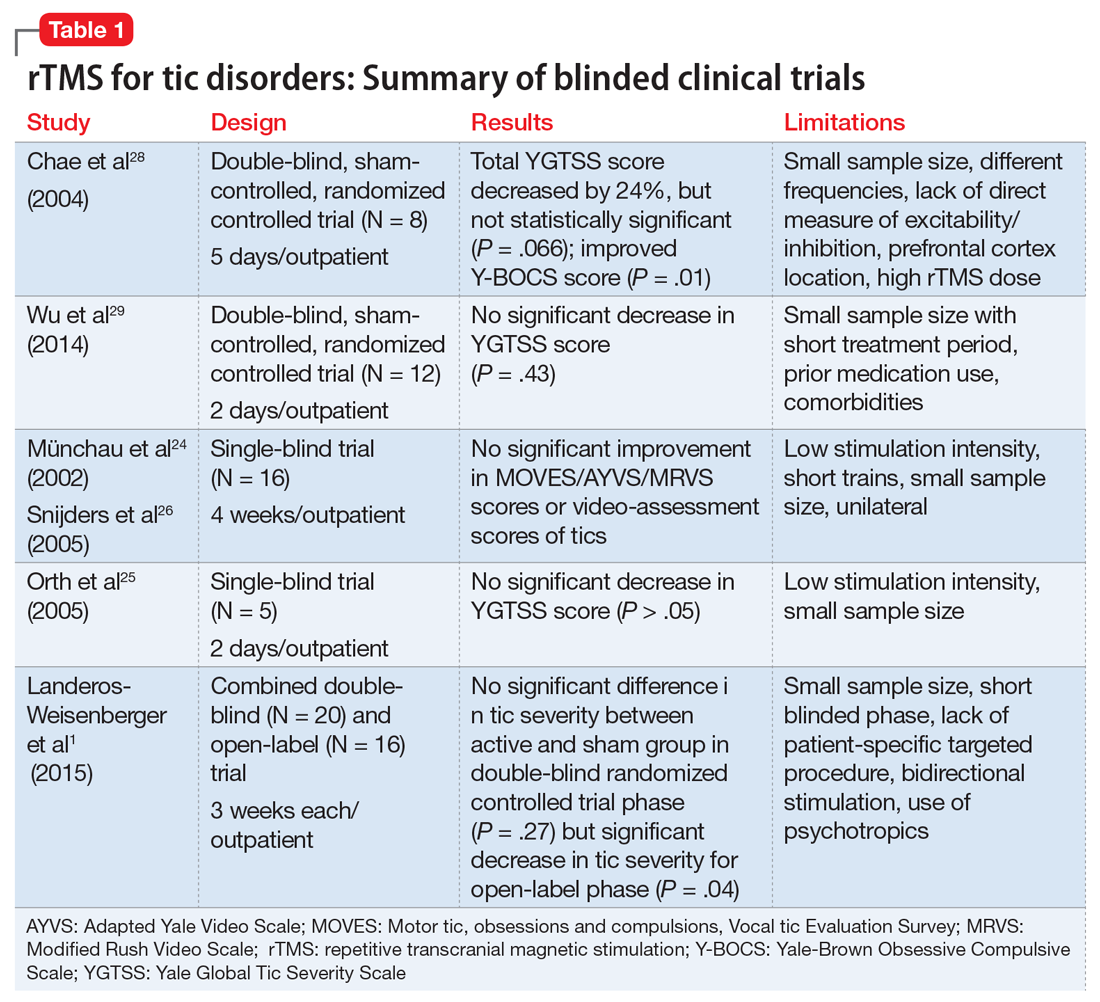

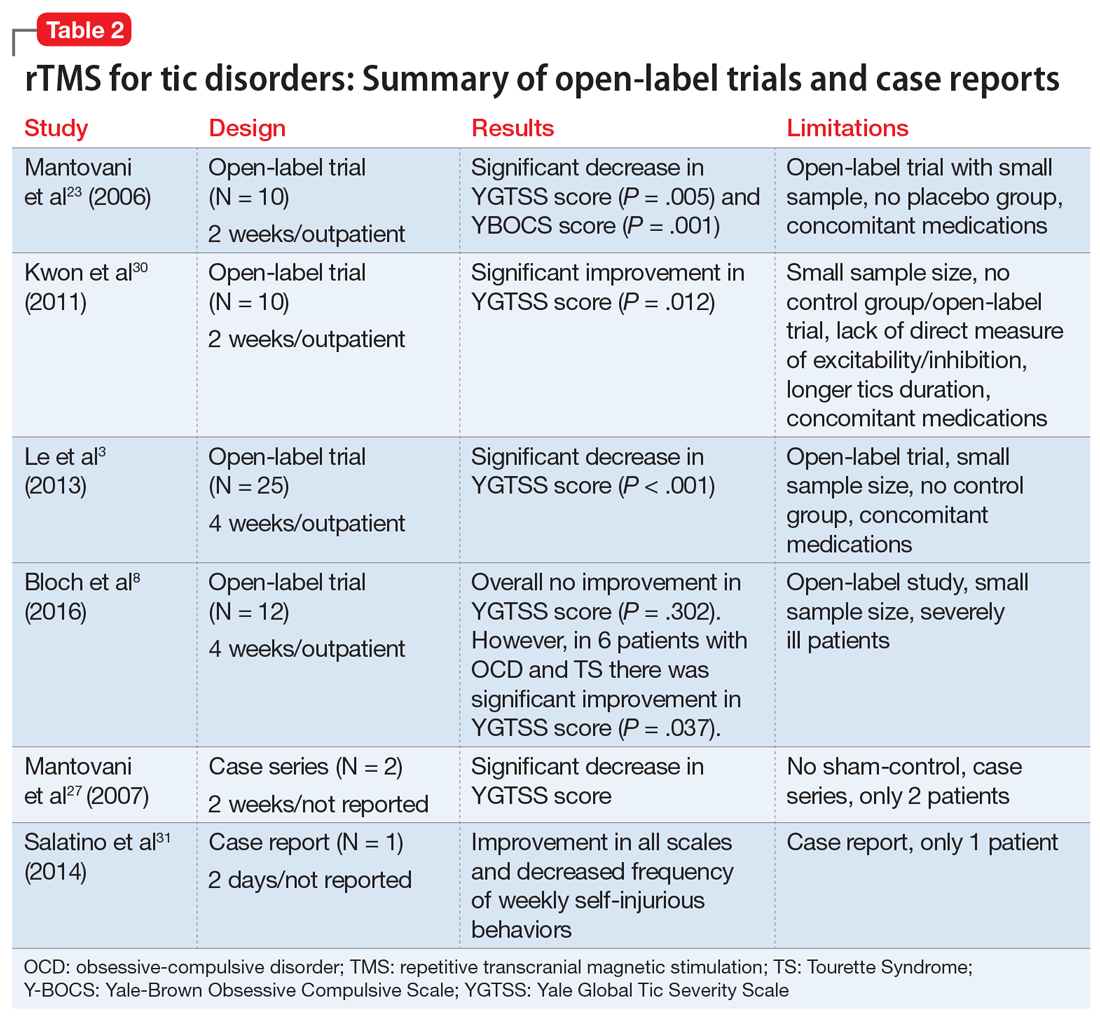

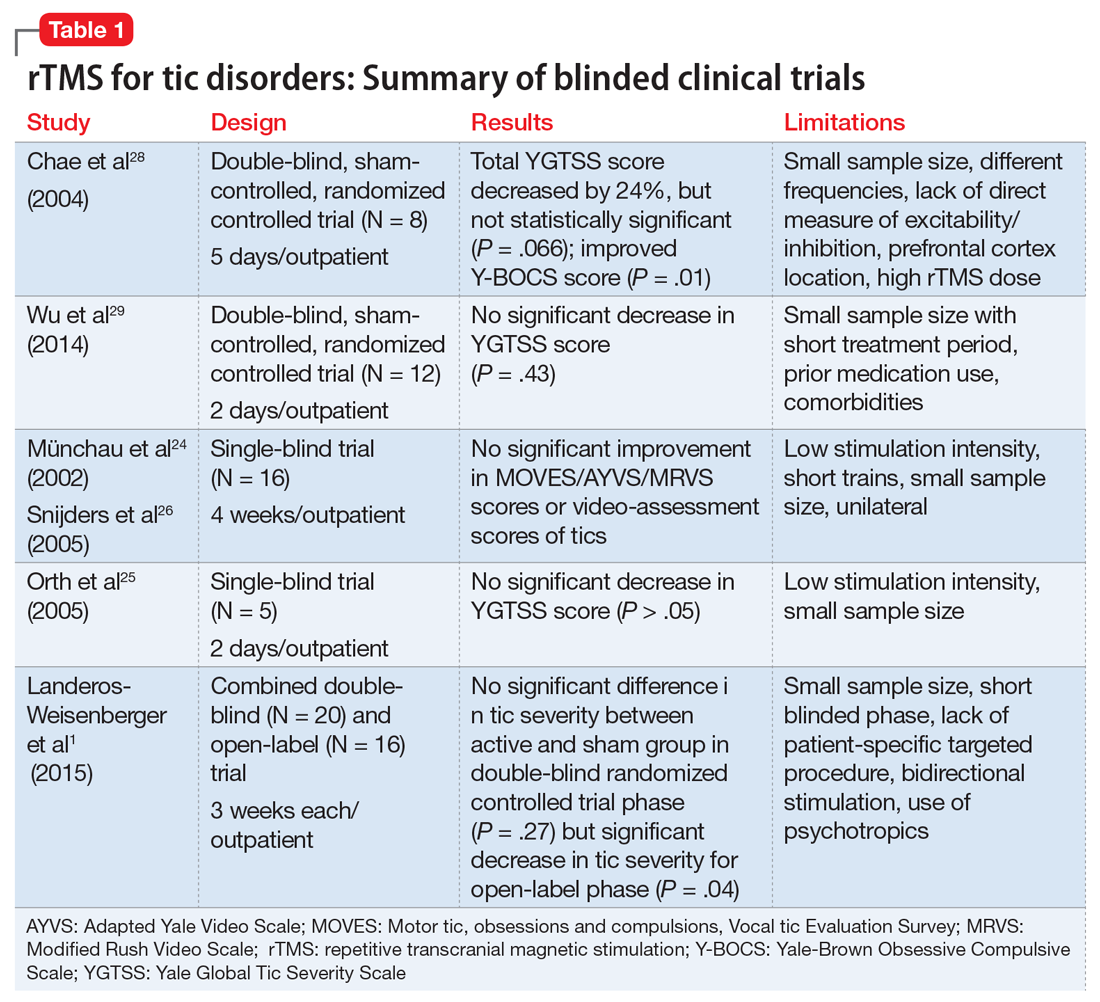

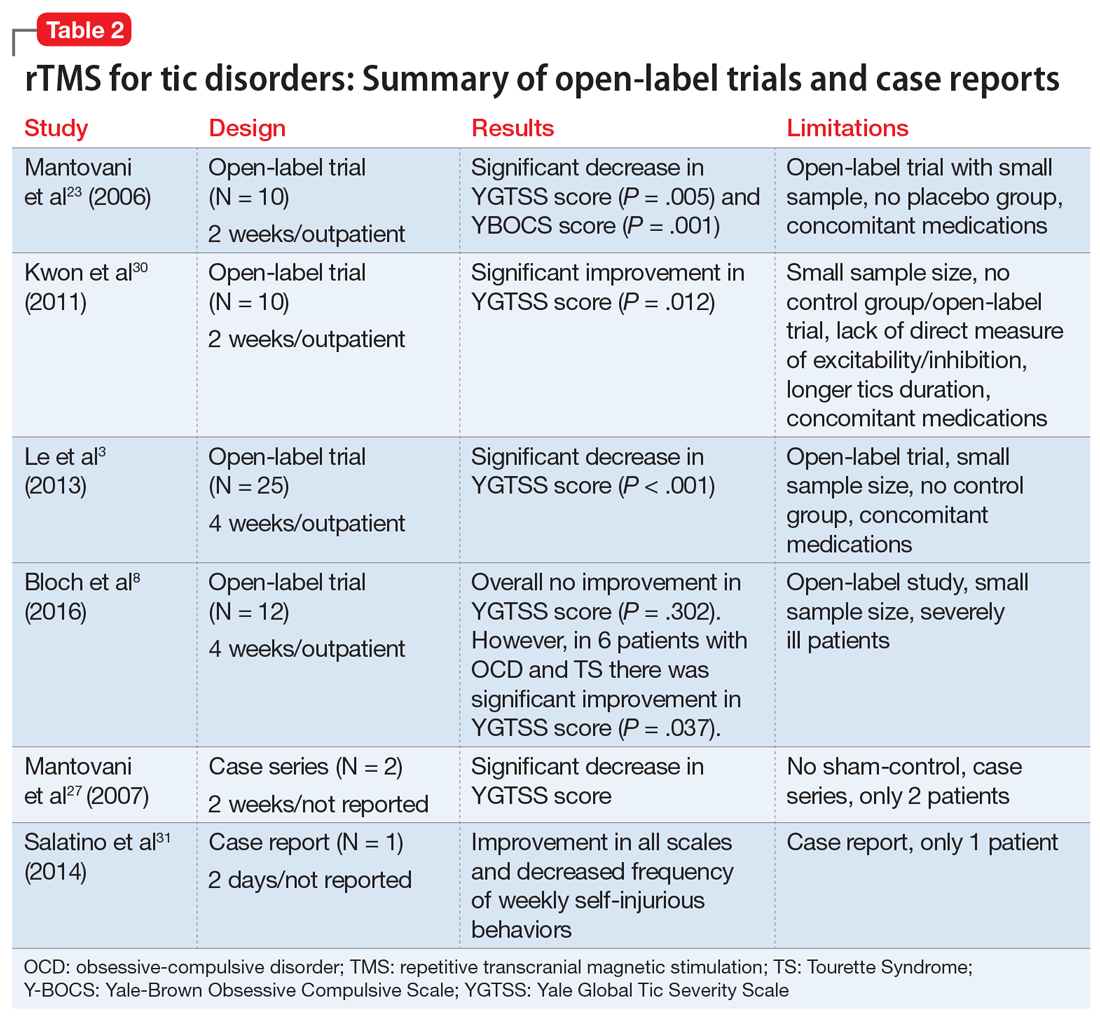

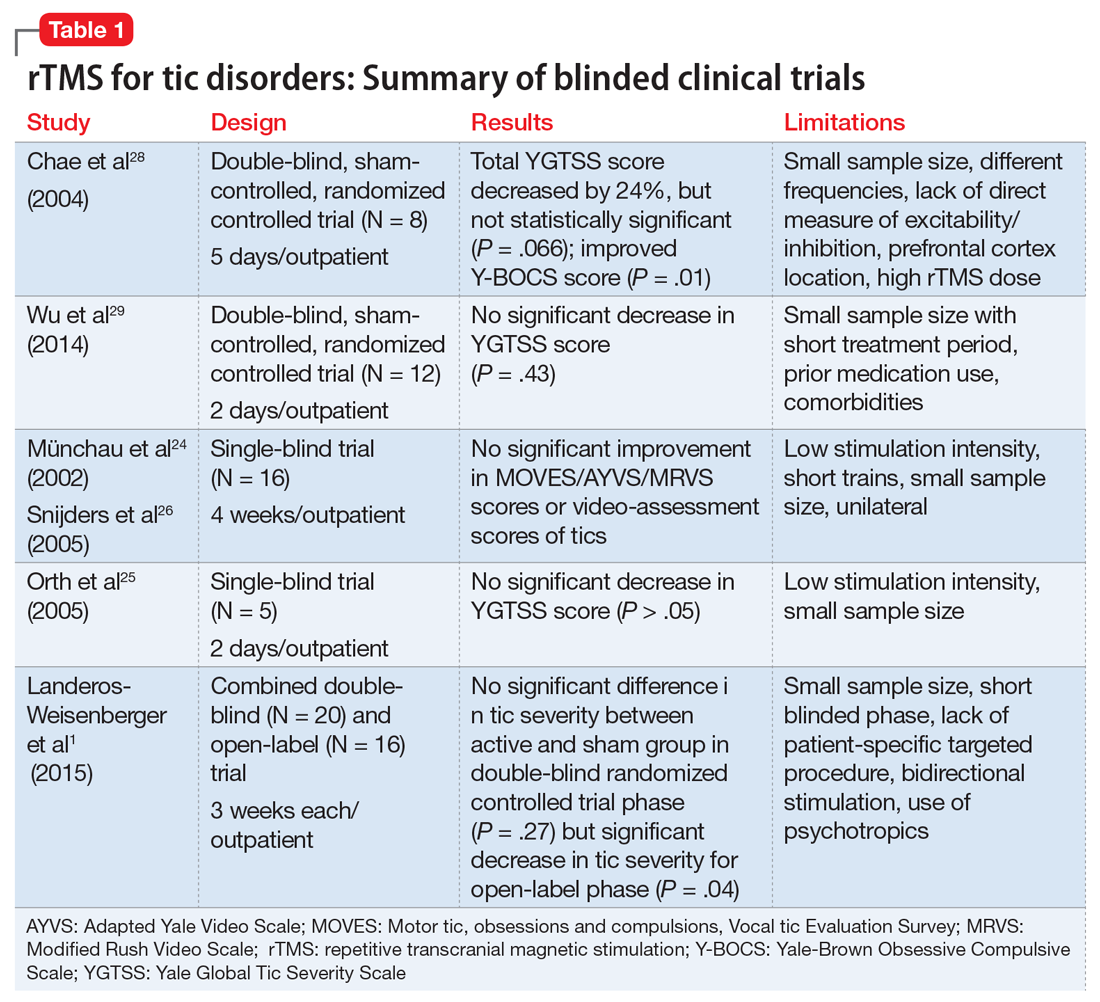

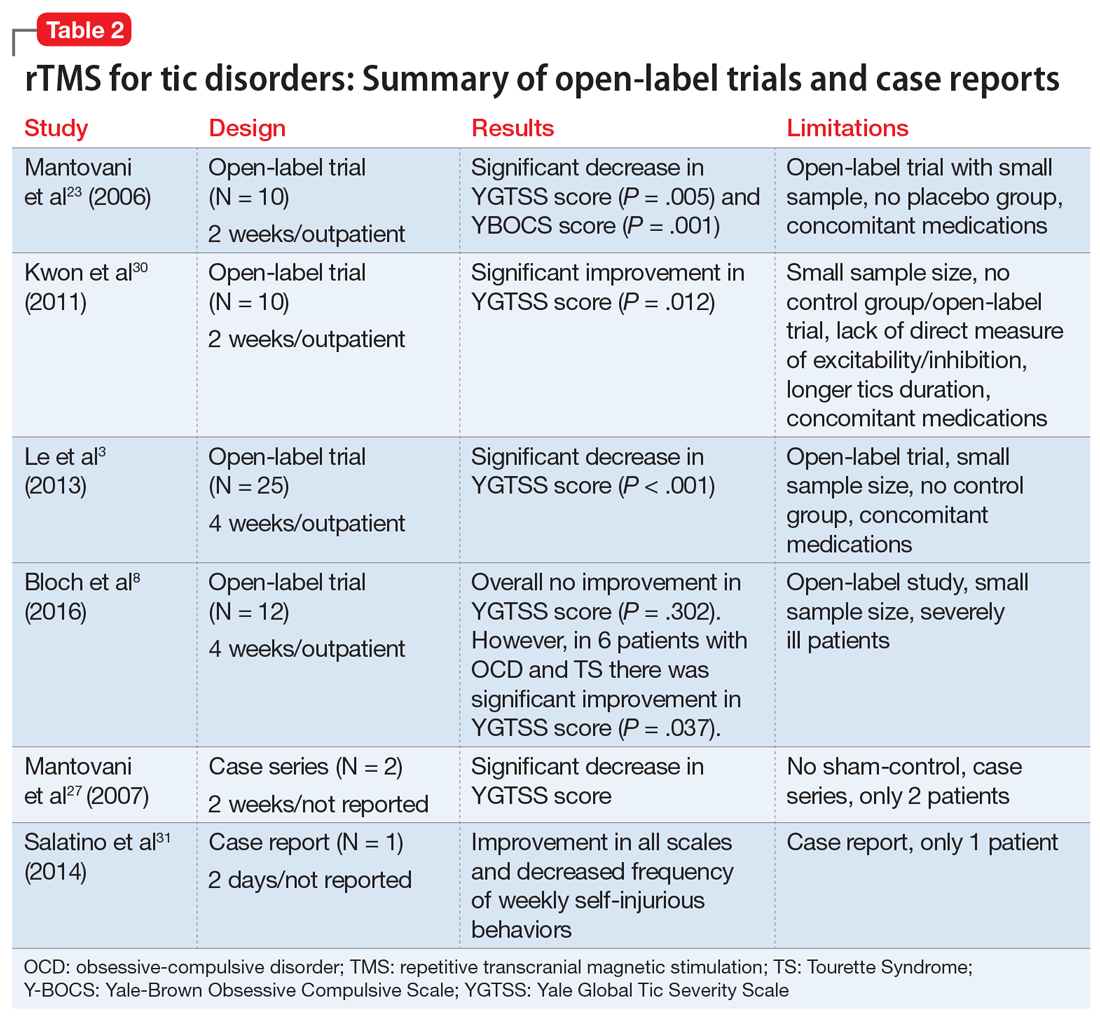

We reviewed the results of 11 studies that described the use of rTMS for TS and other tic disorders (Table 11,24-26,28,29 and Table 23,8,23,27,30,31). They included:

- 2 double-blind, randomized controlled trials28,29

- 2 single-blind trials24-26

- 1 double-blind trial with an open-label extension1

- 4 open-label studies3,8,23,30

- 1 case series27 and 1 case report.31

Study characteristics. In the 11 studies we reviewed, the duration of rTMS treatment varied from 2 days to 4 weeks. The pulses used were 900, 1,200, 1,800, and 2,400 per day, and the frequencies were 1 Hz, 4 Hz, 15 Hz and 30 Hz. Seven studies did not use placebo- or sham-controlled arms.1,3,8,23,27,30,31

Efficacy. Two double-blind trials28,29 found no significant improvement in tic severity in patients treated with rTMS (P = .066 and P = .43, respectively). In addition, the 2 single-blind studies showed no beneficial effects of rTMS for patients with tics (P > .05).24-26 However, 3 of the 4 open-label studies found a significant improvement in tics.3,23,30 In one of the double-blind trials, researchers added an open-label extension phase.1 They found no significant results in the double-blind phase of the study (P = .27), but in the open-label phase, patients experienced a significant improvement in tic severity (P = .04).1 Lastly, the case series and case report found an improvement in tic severity and improvement in TS symptoms, respectively, with rTMS treatment.

rTMS might also improve symptoms of OCD that may co-occur with TS.8,23,28 Two studies found significant improvement in tic severity in a subgroup of patients suffering from comorbid OCD.8,28

Continue to: Safety profile and adverse effects

Safety profile and adverse effects. In the studies we reviewed, the adverse effects associated with rTMS included headache (45%),1,8,24,26,28,29 scalp pain (18%),8,30 self-injurious crisis (9%),31 abdominal pain (9%),29 red eyes (9%),29 neck pain (9%),1 muscle sprain (9%),1 tiredness (9%),24,26 and increase in motor excitability (9%).28 There were no severe adverse effects reported in any of the studies. The self-injurious crisis reported by a patient early in one study as a seizure was later ruled out after careful clinical and electroencephalographic evaluation. This patient demonstrated self-injurious behaviors prior to the treatment, and overall there was a reduction in frequency and intensity of self-injurious behavior as well as an improvement in tics.31

Dissimilar studies

There was great heterogeneity among the 11 studies we reviewed. One case series27 and one case report31 found significant improvement in tics, but these studies did not have control groups. Both studies employed rTMS with a frequency of 1 Hz and between 900 to 1,200 pulses per day. Three open-label studies that found significant improvement in tic severity used the same frequency of stimulation (1 Hz with 1,200 pulses per day).3,23,30 All studies we analyzed differed in the total number of rTMS sessions and number of trains per stimulation.

The studies also differed in terms of the age of the participants. Some studies focused primarily on pediatric patients,3,30 but many of them also included adults. The main limitations of the 11 studies included a small sample size,1,3,8,23-25,28-30 no placebo or controlled arm,1,3,8,23,27,30,31 concomitant psychiatric comorbidities8,28,29 or medications,1,3,23,29,30 low stimulation intensity,24-26 and use of short trains24,26 or unilateral cerebral stimulation.24,26 Among the blinded studies, limitations included a small sample size, prior medications used, comorbidities, low stimulation intensity, and high rTMS dose.1,24-26,28,29

A possible option for treatment-resistant tics

We cannot offer a definitive conclusion on the safety and effectiveness of rTMS for the treatment of TS and other tic disorders because of the inconsistent results, heterogeneity, and small sample sizes of the studies we analyzed. Higher-quality studies failed to find evidence supporting the use of rTMS for treating TS and other tics disorders, but open-label studies and case reports found significant improvements. In light of this evidence and the treatment’s relatively favorable adverse-effects profile, rTMS might be an option for certain patients with treatment-resistant tics, particularly those with comorbid OCD symptoms.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

The evidence for using repetitive transcranial stimulation (rTMS) to treat patients with Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders is mixed. Higher-quality studies have found no significant improvements, whereas open-label studies and case studies have. Although not recommended for the routine treatment of tic disorders, rTMS may be an option for patients with treatment-resistant tics, particularly those with comorbid obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Related Resources

- Tourette Association of America. https://www.tourette.org/.

- Harris E. Children with tic disorders: How to match treatment with symptoms. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(3):29-36.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Clonidine • Catapres, Duraclon

Guanfacine • Intuniv, Tenex

Haloperidol • Haldol

Pimozide • Orap

1. Landeros-Weisenberger A, Mantovani A, Motlagh MG, et al. Randomized sham controlled double-blind trial of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for adults with severe Tourette syndrome. Brain Stimulat. 2015;8(3):574-581.

2. Kamble N, Netravathi M, Pal PK. Therapeutic applications of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in movement disorders: a review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(7):695-707.

3. Le K, Liu L, Sun M, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation at 1 Hertz improves clinical symptoms in children with Tourette syndrome for at least 6 months. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20(2):257-262.

4. Cavanna AE, Seri S. Tourette’s syndrome. BMJ. 2013;347:f4964. doi:10.1136/bmj.f4964.

5. Leckman JF, Bloch MH, Scahill L, et al. Tourette syndrome: the self under siege. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(8):642-649.

6. Bloch MH, Peterson BS, Scahill L, et al. Adulthood outcome of tic and obsessive-compulsive symptom severity in children with Tourette syndrome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(1):65-69.

7. Bloch M, State M, Pittenger C. Recent advances in Tourette syndrome. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24(2):119-125.

8. Bloch Y, Arad S, Levkovitz Y. Deep TMS add-on treatment for intractable Tourette syndrome: a feasibility study. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016;17(7):557-561.

9. Robertson MM. The Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: the current status. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2012;97(5):166-175.

10. Párraga HC, Harris KM, Párraga KL, et al. An overview of the treatment of Tourette’s disorder and tics. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(4):249-262.

11. Du JC, Chiu TF, Lee KM, et al. Tourette syndrome in children: an updated review. Pediatr Neonatol. 2010;51(5):255-264.

12. Malizia AL. What do brain imaging studies tell us about anxiety disorders? J Psychopharmacol. 1999;13(4):372-378.

13. Di Lazzaro V, Oliviero A, Berardelli A, et al. Direct demonstration of the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on the excitability of the human motor cortex. Exp Brain Res. 2002;144(4):549-553.

14. Olson LL, Singer HS, Goodman WK, et al. Tourette syndrome: diagnosis, strategies, therapies, pathogenesis, and future research directions. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(8):630-641.

15. Gerard E, Peterson BS. Developmental processes and brain imaging studies in Tourette syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(1):13-22.

16. Kurlan R. Hypothesis II: Tourette’s syndrome is part of a clinical spectrum that includes normal brain development. Arch Neurol. 1994;51(11):1145-1150.

17. Peterson BS. Neuroimaging in child and adolescent neuropsychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(12):1560-1576.

18. Sheppard DM, Bradshaw JL, Purcell R, et al. Tourette’s and comorbid syndromes: obsessive compulsive and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. A common etiology? Clin Psychol Rev. 1999;19(5):531-552.

19. Bohlhalter S, Goldfine A, Matteson S, et al. Neural correlates of tic generation in Tourette syndrome: an event-related functional MRI study. Brain. 2006;129(pt 8):2029-2037.

20. Hampson M, Tokoglu F, King RA, et al. Brain areas coactivating with motor cortex during chronic motor tics and intentional movements. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(7):594-599.

21. Eichele H, Plessen KJ. Neural plasticity in functional and anatomical MRI studies of children with Tourette syndrome. Behav Neurol. 2013;27(1):33-45.

22. Neuner I, Schneider F, Shah NJ. Functional neuroanatomy of tics. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;112:35-71.

23. Mantovani A, Lisanby SH, Pieraccini F, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and Tourette’s syndrome (TS). Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;9(1):95-100.

24. Münchau A, Bloem BR, Thilo KV, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for Tourette syndrome. Neurology. 2002;59(11):1789-1791.

25. Orth M, Kirby R, Richardson MP, et al. Subthreshold rTMS over pre-motor cortex has no effect on tics in patients with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116(4):764-768.

26. Snijders AH, Bloem BR, Orth M, et al. Video assessment of rTMS for Tourette syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(12):1743-1744.

27. Mantovani A, Leckman JF, Grantz H, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the supplementary motor area in the treatment of Tourette syndrome: report of two cases. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118(10):2314-2315.

28. Chae JH, Nahas Z, Wassermann E, et al. A pilot safety study of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in Tourette’s syndrome. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2004;17(2):109-117.

29. Wu SW, Maloney T, Gilbert DL, et al. Functional MRI-navigated repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation over supplementary motor area in chronic tic disorders. Brain Stimul. 2014;7(2):212-218.

30. Kwon HJ, Lim WS, Lim MH, et al. 1-Hz low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in children with Tourette’s syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 2011;492(1):1-4.

31. Salatino A, Momo E, Nobili M, et al. Awareness of symptoms amelioration following low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in a patient with Tourette syndrome and comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder. Brain Stimulat. 2014;7(2):341-343.

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a chronic neuropsychiatric disorder occurring in early childhood or adolescence that’s characterized by multiple motor and vocal tics that are usually preceded by premonitory urges.1,2 Usually, the tics are repetitive, sudden, stereotypical, non-rhythmic movements and/or vocalizations.3,4 Individuals with TS and other tic disorders often experience impulsivity, aggression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and various mood and anxiety disorders.3 Psychosocial issues may include having low self-esteem, increased family conflict, and poor social skills. Males are affected 3 to 5 times more often than females.3

There is no definitive treatment for TS. Commonly used interventions are pharmacotherapy and/or behavioral therapy, which includes supportive psychotherapy, habit reversal training, exposure with response prevention, relaxation therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and self-monitoring. Pharmacotherapy for TS and other tic disorders consists mainly of antipsychotics such as haloperidol, pimozide, and aripiprazole, and alpha-2 agonists (guanfacine and clonidine).4,8-10 Unfortunately, not all children respond to these medications, and these agents are associated with multiple adverse effects.11 Therefore, there is a need for additional treatment options for patients with TS and other tic disorders, especially those who are not helped by conventional treatments.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a non-invasive therapeutic technique in which high-intensity magnetic impulses are delivered through an electromagnetic coil placed on the patient’s scalp to stimulate cortical neurons. The effect is determined by various parameters, including the intensity, frequency, pulse number, duration, coil location, and type of coil.3,8

rTMS is FDA-approved for treating depression, and has been used to treat anxiety disorders, Parkinson’s disease, chronic pain syndromes, and dystonia.12,13 Researchers have begun to evaluate the usefulness of rTMS for patients with TS or other tic disorders. In this article, we review the findings of 11 studies—9 clinical trials and 2 case studies—that evaluated rTMS as a treatment option for patients with tic disorders.

A proposed mechanism of action

TS is believed to be caused by multiple factors, including neurotransmitter imbalances and genetic, environmental, and psychosocial factors.14 Evidence strongly suggests the involvement of the motor cortex, basal ganglia, and reticular activating system in the expression of TS.2,15-17

Researchers have consistently identified networks of regions in the brain, including the supplementary motor area (SMA), that are active in the seconds before tics occur in patients with these disorders.6,18-22 The SMA modulates the way information is channeled between motor circuits, the limbic system, and the cognitive processes.3,23-26 The SMA can be used as a target for focal brain stimulation to modulate activity in those circuits and improve symptoms in resistant patients. Recent rTMS studies that targeted the SMA have found that stimulation to this area may be an effective way to treat TS.19,20,23,27

Continue to: rTMS for tics: Mixed evidence

rTMS for tics: Mixed evidence

We reviewed the results of 11 studies that described the use of rTMS for TS and other tic disorders (Table 11,24-26,28,29 and Table 23,8,23,27,30,31). They included:

- 2 double-blind, randomized controlled trials28,29

- 2 single-blind trials24-26

- 1 double-blind trial with an open-label extension1

- 4 open-label studies3,8,23,30

- 1 case series27 and 1 case report.31

Study characteristics. In the 11 studies we reviewed, the duration of rTMS treatment varied from 2 days to 4 weeks. The pulses used were 900, 1,200, 1,800, and 2,400 per day, and the frequencies were 1 Hz, 4 Hz, 15 Hz and 30 Hz. Seven studies did not use placebo- or sham-controlled arms.1,3,8,23,27,30,31

Efficacy. Two double-blind trials28,29 found no significant improvement in tic severity in patients treated with rTMS (P = .066 and P = .43, respectively). In addition, the 2 single-blind studies showed no beneficial effects of rTMS for patients with tics (P > .05).24-26 However, 3 of the 4 open-label studies found a significant improvement in tics.3,23,30 In one of the double-blind trials, researchers added an open-label extension phase.1 They found no significant results in the double-blind phase of the study (P = .27), but in the open-label phase, patients experienced a significant improvement in tic severity (P = .04).1 Lastly, the case series and case report found an improvement in tic severity and improvement in TS symptoms, respectively, with rTMS treatment.

rTMS might also improve symptoms of OCD that may co-occur with TS.8,23,28 Two studies found significant improvement in tic severity in a subgroup of patients suffering from comorbid OCD.8,28

Continue to: Safety profile and adverse effects

Safety profile and adverse effects. In the studies we reviewed, the adverse effects associated with rTMS included headache (45%),1,8,24,26,28,29 scalp pain (18%),8,30 self-injurious crisis (9%),31 abdominal pain (9%),29 red eyes (9%),29 neck pain (9%),1 muscle sprain (9%),1 tiredness (9%),24,26 and increase in motor excitability (9%).28 There were no severe adverse effects reported in any of the studies. The self-injurious crisis reported by a patient early in one study as a seizure was later ruled out after careful clinical and electroencephalographic evaluation. This patient demonstrated self-injurious behaviors prior to the treatment, and overall there was a reduction in frequency and intensity of self-injurious behavior as well as an improvement in tics.31

Dissimilar studies

There was great heterogeneity among the 11 studies we reviewed. One case series27 and one case report31 found significant improvement in tics, but these studies did not have control groups. Both studies employed rTMS with a frequency of 1 Hz and between 900 to 1,200 pulses per day. Three open-label studies that found significant improvement in tic severity used the same frequency of stimulation (1 Hz with 1,200 pulses per day).3,23,30 All studies we analyzed differed in the total number of rTMS sessions and number of trains per stimulation.

The studies also differed in terms of the age of the participants. Some studies focused primarily on pediatric patients,3,30 but many of them also included adults. The main limitations of the 11 studies included a small sample size,1,3,8,23-25,28-30 no placebo or controlled arm,1,3,8,23,27,30,31 concomitant psychiatric comorbidities8,28,29 or medications,1,3,23,29,30 low stimulation intensity,24-26 and use of short trains24,26 or unilateral cerebral stimulation.24,26 Among the blinded studies, limitations included a small sample size, prior medications used, comorbidities, low stimulation intensity, and high rTMS dose.1,24-26,28,29

A possible option for treatment-resistant tics

We cannot offer a definitive conclusion on the safety and effectiveness of rTMS for the treatment of TS and other tic disorders because of the inconsistent results, heterogeneity, and small sample sizes of the studies we analyzed. Higher-quality studies failed to find evidence supporting the use of rTMS for treating TS and other tics disorders, but open-label studies and case reports found significant improvements. In light of this evidence and the treatment’s relatively favorable adverse-effects profile, rTMS might be an option for certain patients with treatment-resistant tics, particularly those with comorbid OCD symptoms.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

The evidence for using repetitive transcranial stimulation (rTMS) to treat patients with Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders is mixed. Higher-quality studies have found no significant improvements, whereas open-label studies and case studies have. Although not recommended for the routine treatment of tic disorders, rTMS may be an option for patients with treatment-resistant tics, particularly those with comorbid obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Related Resources

- Tourette Association of America. https://www.tourette.org/.

- Harris E. Children with tic disorders: How to match treatment with symptoms. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(3):29-36.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Clonidine • Catapres, Duraclon

Guanfacine • Intuniv, Tenex

Haloperidol • Haldol

Pimozide • Orap

Tourette syndrome (TS) is a chronic neuropsychiatric disorder occurring in early childhood or adolescence that’s characterized by multiple motor and vocal tics that are usually preceded by premonitory urges.1,2 Usually, the tics are repetitive, sudden, stereotypical, non-rhythmic movements and/or vocalizations.3,4 Individuals with TS and other tic disorders often experience impulsivity, aggression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and various mood and anxiety disorders.3 Psychosocial issues may include having low self-esteem, increased family conflict, and poor social skills. Males are affected 3 to 5 times more often than females.3

There is no definitive treatment for TS. Commonly used interventions are pharmacotherapy and/or behavioral therapy, which includes supportive psychotherapy, habit reversal training, exposure with response prevention, relaxation therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and self-monitoring. Pharmacotherapy for TS and other tic disorders consists mainly of antipsychotics such as haloperidol, pimozide, and aripiprazole, and alpha-2 agonists (guanfacine and clonidine).4,8-10 Unfortunately, not all children respond to these medications, and these agents are associated with multiple adverse effects.11 Therefore, there is a need for additional treatment options for patients with TS and other tic disorders, especially those who are not helped by conventional treatments.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is a non-invasive therapeutic technique in which high-intensity magnetic impulses are delivered through an electromagnetic coil placed on the patient’s scalp to stimulate cortical neurons. The effect is determined by various parameters, including the intensity, frequency, pulse number, duration, coil location, and type of coil.3,8

rTMS is FDA-approved for treating depression, and has been used to treat anxiety disorders, Parkinson’s disease, chronic pain syndromes, and dystonia.12,13 Researchers have begun to evaluate the usefulness of rTMS for patients with TS or other tic disorders. In this article, we review the findings of 11 studies—9 clinical trials and 2 case studies—that evaluated rTMS as a treatment option for patients with tic disorders.

A proposed mechanism of action

TS is believed to be caused by multiple factors, including neurotransmitter imbalances and genetic, environmental, and psychosocial factors.14 Evidence strongly suggests the involvement of the motor cortex, basal ganglia, and reticular activating system in the expression of TS.2,15-17

Researchers have consistently identified networks of regions in the brain, including the supplementary motor area (SMA), that are active in the seconds before tics occur in patients with these disorders.6,18-22 The SMA modulates the way information is channeled between motor circuits, the limbic system, and the cognitive processes.3,23-26 The SMA can be used as a target for focal brain stimulation to modulate activity in those circuits and improve symptoms in resistant patients. Recent rTMS studies that targeted the SMA have found that stimulation to this area may be an effective way to treat TS.19,20,23,27

Continue to: rTMS for tics: Mixed evidence

rTMS for tics: Mixed evidence

We reviewed the results of 11 studies that described the use of rTMS for TS and other tic disorders (Table 11,24-26,28,29 and Table 23,8,23,27,30,31). They included:

- 2 double-blind, randomized controlled trials28,29

- 2 single-blind trials24-26

- 1 double-blind trial with an open-label extension1

- 4 open-label studies3,8,23,30

- 1 case series27 and 1 case report.31

Study characteristics. In the 11 studies we reviewed, the duration of rTMS treatment varied from 2 days to 4 weeks. The pulses used were 900, 1,200, 1,800, and 2,400 per day, and the frequencies were 1 Hz, 4 Hz, 15 Hz and 30 Hz. Seven studies did not use placebo- or sham-controlled arms.1,3,8,23,27,30,31

Efficacy. Two double-blind trials28,29 found no significant improvement in tic severity in patients treated with rTMS (P = .066 and P = .43, respectively). In addition, the 2 single-blind studies showed no beneficial effects of rTMS for patients with tics (P > .05).24-26 However, 3 of the 4 open-label studies found a significant improvement in tics.3,23,30 In one of the double-blind trials, researchers added an open-label extension phase.1 They found no significant results in the double-blind phase of the study (P = .27), but in the open-label phase, patients experienced a significant improvement in tic severity (P = .04).1 Lastly, the case series and case report found an improvement in tic severity and improvement in TS symptoms, respectively, with rTMS treatment.

rTMS might also improve symptoms of OCD that may co-occur with TS.8,23,28 Two studies found significant improvement in tic severity in a subgroup of patients suffering from comorbid OCD.8,28

Continue to: Safety profile and adverse effects

Safety profile and adverse effects. In the studies we reviewed, the adverse effects associated with rTMS included headache (45%),1,8,24,26,28,29 scalp pain (18%),8,30 self-injurious crisis (9%),31 abdominal pain (9%),29 red eyes (9%),29 neck pain (9%),1 muscle sprain (9%),1 tiredness (9%),24,26 and increase in motor excitability (9%).28 There were no severe adverse effects reported in any of the studies. The self-injurious crisis reported by a patient early in one study as a seizure was later ruled out after careful clinical and electroencephalographic evaluation. This patient demonstrated self-injurious behaviors prior to the treatment, and overall there was a reduction in frequency and intensity of self-injurious behavior as well as an improvement in tics.31

Dissimilar studies

There was great heterogeneity among the 11 studies we reviewed. One case series27 and one case report31 found significant improvement in tics, but these studies did not have control groups. Both studies employed rTMS with a frequency of 1 Hz and between 900 to 1,200 pulses per day. Three open-label studies that found significant improvement in tic severity used the same frequency of stimulation (1 Hz with 1,200 pulses per day).3,23,30 All studies we analyzed differed in the total number of rTMS sessions and number of trains per stimulation.

The studies also differed in terms of the age of the participants. Some studies focused primarily on pediatric patients,3,30 but many of them also included adults. The main limitations of the 11 studies included a small sample size,1,3,8,23-25,28-30 no placebo or controlled arm,1,3,8,23,27,30,31 concomitant psychiatric comorbidities8,28,29 or medications,1,3,23,29,30 low stimulation intensity,24-26 and use of short trains24,26 or unilateral cerebral stimulation.24,26 Among the blinded studies, limitations included a small sample size, prior medications used, comorbidities, low stimulation intensity, and high rTMS dose.1,24-26,28,29

A possible option for treatment-resistant tics

We cannot offer a definitive conclusion on the safety and effectiveness of rTMS for the treatment of TS and other tic disorders because of the inconsistent results, heterogeneity, and small sample sizes of the studies we analyzed. Higher-quality studies failed to find evidence supporting the use of rTMS for treating TS and other tics disorders, but open-label studies and case reports found significant improvements. In light of this evidence and the treatment’s relatively favorable adverse-effects profile, rTMS might be an option for certain patients with treatment-resistant tics, particularly those with comorbid OCD symptoms.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

The evidence for using repetitive transcranial stimulation (rTMS) to treat patients with Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders is mixed. Higher-quality studies have found no significant improvements, whereas open-label studies and case studies have. Although not recommended for the routine treatment of tic disorders, rTMS may be an option for patients with treatment-resistant tics, particularly those with comorbid obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

Related Resources

- Tourette Association of America. https://www.tourette.org/.

- Harris E. Children with tic disorders: How to match treatment with symptoms. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(3):29-36.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Clonidine • Catapres, Duraclon

Guanfacine • Intuniv, Tenex

Haloperidol • Haldol

Pimozide • Orap

1. Landeros-Weisenberger A, Mantovani A, Motlagh MG, et al. Randomized sham controlled double-blind trial of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for adults with severe Tourette syndrome. Brain Stimulat. 2015;8(3):574-581.

2. Kamble N, Netravathi M, Pal PK. Therapeutic applications of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in movement disorders: a review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(7):695-707.

3. Le K, Liu L, Sun M, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation at 1 Hertz improves clinical symptoms in children with Tourette syndrome for at least 6 months. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20(2):257-262.

4. Cavanna AE, Seri S. Tourette’s syndrome. BMJ. 2013;347:f4964. doi:10.1136/bmj.f4964.

5. Leckman JF, Bloch MH, Scahill L, et al. Tourette syndrome: the self under siege. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(8):642-649.

6. Bloch MH, Peterson BS, Scahill L, et al. Adulthood outcome of tic and obsessive-compulsive symptom severity in children with Tourette syndrome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(1):65-69.

7. Bloch M, State M, Pittenger C. Recent advances in Tourette syndrome. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24(2):119-125.

8. Bloch Y, Arad S, Levkovitz Y. Deep TMS add-on treatment for intractable Tourette syndrome: a feasibility study. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016;17(7):557-561.

9. Robertson MM. The Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: the current status. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2012;97(5):166-175.

10. Párraga HC, Harris KM, Párraga KL, et al. An overview of the treatment of Tourette’s disorder and tics. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(4):249-262.

11. Du JC, Chiu TF, Lee KM, et al. Tourette syndrome in children: an updated review. Pediatr Neonatol. 2010;51(5):255-264.

12. Malizia AL. What do brain imaging studies tell us about anxiety disorders? J Psychopharmacol. 1999;13(4):372-378.

13. Di Lazzaro V, Oliviero A, Berardelli A, et al. Direct demonstration of the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on the excitability of the human motor cortex. Exp Brain Res. 2002;144(4):549-553.

14. Olson LL, Singer HS, Goodman WK, et al. Tourette syndrome: diagnosis, strategies, therapies, pathogenesis, and future research directions. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(8):630-641.

15. Gerard E, Peterson BS. Developmental processes and brain imaging studies in Tourette syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(1):13-22.

16. Kurlan R. Hypothesis II: Tourette’s syndrome is part of a clinical spectrum that includes normal brain development. Arch Neurol. 1994;51(11):1145-1150.

17. Peterson BS. Neuroimaging in child and adolescent neuropsychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(12):1560-1576.

18. Sheppard DM, Bradshaw JL, Purcell R, et al. Tourette’s and comorbid syndromes: obsessive compulsive and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. A common etiology? Clin Psychol Rev. 1999;19(5):531-552.

19. Bohlhalter S, Goldfine A, Matteson S, et al. Neural correlates of tic generation in Tourette syndrome: an event-related functional MRI study. Brain. 2006;129(pt 8):2029-2037.

20. Hampson M, Tokoglu F, King RA, et al. Brain areas coactivating with motor cortex during chronic motor tics and intentional movements. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(7):594-599.

21. Eichele H, Plessen KJ. Neural plasticity in functional and anatomical MRI studies of children with Tourette syndrome. Behav Neurol. 2013;27(1):33-45.

22. Neuner I, Schneider F, Shah NJ. Functional neuroanatomy of tics. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;112:35-71.

23. Mantovani A, Lisanby SH, Pieraccini F, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and Tourette’s syndrome (TS). Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;9(1):95-100.

24. Münchau A, Bloem BR, Thilo KV, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for Tourette syndrome. Neurology. 2002;59(11):1789-1791.

25. Orth M, Kirby R, Richardson MP, et al. Subthreshold rTMS over pre-motor cortex has no effect on tics in patients with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116(4):764-768.

26. Snijders AH, Bloem BR, Orth M, et al. Video assessment of rTMS for Tourette syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(12):1743-1744.

27. Mantovani A, Leckman JF, Grantz H, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the supplementary motor area in the treatment of Tourette syndrome: report of two cases. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118(10):2314-2315.

28. Chae JH, Nahas Z, Wassermann E, et al. A pilot safety study of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in Tourette’s syndrome. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2004;17(2):109-117.

29. Wu SW, Maloney T, Gilbert DL, et al. Functional MRI-navigated repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation over supplementary motor area in chronic tic disorders. Brain Stimul. 2014;7(2):212-218.

30. Kwon HJ, Lim WS, Lim MH, et al. 1-Hz low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in children with Tourette’s syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 2011;492(1):1-4.

31. Salatino A, Momo E, Nobili M, et al. Awareness of symptoms amelioration following low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in a patient with Tourette syndrome and comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder. Brain Stimulat. 2014;7(2):341-343.

1. Landeros-Weisenberger A, Mantovani A, Motlagh MG, et al. Randomized sham controlled double-blind trial of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for adults with severe Tourette syndrome. Brain Stimulat. 2015;8(3):574-581.

2. Kamble N, Netravathi M, Pal PK. Therapeutic applications of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in movement disorders: a review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(7):695-707.

3. Le K, Liu L, Sun M, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation at 1 Hertz improves clinical symptoms in children with Tourette syndrome for at least 6 months. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20(2):257-262.

4. Cavanna AE, Seri S. Tourette’s syndrome. BMJ. 2013;347:f4964. doi:10.1136/bmj.f4964.

5. Leckman JF, Bloch MH, Scahill L, et al. Tourette syndrome: the self under siege. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(8):642-649.

6. Bloch MH, Peterson BS, Scahill L, et al. Adulthood outcome of tic and obsessive-compulsive symptom severity in children with Tourette syndrome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(1):65-69.

7. Bloch M, State M, Pittenger C. Recent advances in Tourette syndrome. Curr Opin Neurol. 2011;24(2):119-125.

8. Bloch Y, Arad S, Levkovitz Y. Deep TMS add-on treatment for intractable Tourette syndrome: a feasibility study. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2016;17(7):557-561.

9. Robertson MM. The Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: the current status. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2012;97(5):166-175.

10. Párraga HC, Harris KM, Párraga KL, et al. An overview of the treatment of Tourette’s disorder and tics. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(4):249-262.

11. Du JC, Chiu TF, Lee KM, et al. Tourette syndrome in children: an updated review. Pediatr Neonatol. 2010;51(5):255-264.

12. Malizia AL. What do brain imaging studies tell us about anxiety disorders? J Psychopharmacol. 1999;13(4):372-378.

13. Di Lazzaro V, Oliviero A, Berardelli A, et al. Direct demonstration of the effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on the excitability of the human motor cortex. Exp Brain Res. 2002;144(4):549-553.

14. Olson LL, Singer HS, Goodman WK, et al. Tourette syndrome: diagnosis, strategies, therapies, pathogenesis, and future research directions. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(8):630-641.

15. Gerard E, Peterson BS. Developmental processes and brain imaging studies in Tourette syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(1):13-22.

16. Kurlan R. Hypothesis II: Tourette’s syndrome is part of a clinical spectrum that includes normal brain development. Arch Neurol. 1994;51(11):1145-1150.

17. Peterson BS. Neuroimaging in child and adolescent neuropsychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(12):1560-1576.

18. Sheppard DM, Bradshaw JL, Purcell R, et al. Tourette’s and comorbid syndromes: obsessive compulsive and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. A common etiology? Clin Psychol Rev. 1999;19(5):531-552.

19. Bohlhalter S, Goldfine A, Matteson S, et al. Neural correlates of tic generation in Tourette syndrome: an event-related functional MRI study. Brain. 2006;129(pt 8):2029-2037.

20. Hampson M, Tokoglu F, King RA, et al. Brain areas coactivating with motor cortex during chronic motor tics and intentional movements. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(7):594-599.

21. Eichele H, Plessen KJ. Neural plasticity in functional and anatomical MRI studies of children with Tourette syndrome. Behav Neurol. 2013;27(1):33-45.

22. Neuner I, Schneider F, Shah NJ. Functional neuroanatomy of tics. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;112:35-71.

23. Mantovani A, Lisanby SH, Pieraccini F, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and Tourette’s syndrome (TS). Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;9(1):95-100.

24. Münchau A, Bloem BR, Thilo KV, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for Tourette syndrome. Neurology. 2002;59(11):1789-1791.

25. Orth M, Kirby R, Richardson MP, et al. Subthreshold rTMS over pre-motor cortex has no effect on tics in patients with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116(4):764-768.

26. Snijders AH, Bloem BR, Orth M, et al. Video assessment of rTMS for Tourette syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(12):1743-1744.

27. Mantovani A, Leckman JF, Grantz H, et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the supplementary motor area in the treatment of Tourette syndrome: report of two cases. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118(10):2314-2315.

28. Chae JH, Nahas Z, Wassermann E, et al. A pilot safety study of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in Tourette’s syndrome. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2004;17(2):109-117.

29. Wu SW, Maloney T, Gilbert DL, et al. Functional MRI-navigated repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation over supplementary motor area in chronic tic disorders. Brain Stimul. 2014;7(2):212-218.

30. Kwon HJ, Lim WS, Lim MH, et al. 1-Hz low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in children with Tourette’s syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 2011;492(1):1-4.

31. Salatino A, Momo E, Nobili M, et al. Awareness of symptoms amelioration following low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in a patient with Tourette syndrome and comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder. Brain Stimulat. 2014;7(2):341-343.