User login

Dear Dr. Mossman:

In my residency program, we cover the psychiatric emergency room (ER) overnight, and we admit, discharge, and make treatment recommendations without calling the attending psychiatrists about every decision. But if something goes wrong—eg, a discharged patient later commits suicide—I’ve heard that the faculty psychiatrist may be held liable despite never having met the patient. Should we awaken our attendings to discuss every major treatment decision?

Submitted by “Dr. R”

Postgraduate medical training programs in all specialties let interns and residents make judgments and decisions outside the direct supervision of board-certified faculty members. Medical education cannot occur unless doctors learn to take independent responsibility for patients. But if poor decisions by physicians-in-training lead to bad outcomes, might their teachers and training institutions share the blame—and the legal liability for damages?

The answer is “yes.” To understand why, and to learn about how Dr. R’s residency program should address this possibility, we’ll cover:

• the theory of respondeat superior

• factors affecting potential vicarious liability

• how postgraduate training balances supervision needs with letting residents get real-world treatment experience.

Vicarious liability

In general, if Person A injures Person B, Person B may initiate a tort action against Person A to seek monetary compensation. If the injury occurred while Person A was working for Person C, then under a legal doctrine called respondeat superior (Latin for “let the master answer”), courts may allow Person B to sue Person C, too, even if Person C wasn’t present when the injury occurred and did nothing that harmed Person B directly.

Respondeat superior imposes vicarious liability on an employer for negligent acts by employees who are “performing work assigned by the employer or engaging in a course of conduct subject to the employer’s control.”1 The doctrine extends back to 17th-century English courts and originated under the theory that, during a servant’s employment, one may presume that the servant acted by his master’s authority.2

Modern authors state that the justification for imposing vicarious liability “is largely one of public or social policy under which it has been determined that, irrespective of fault, a party should be held to respond for the acts of another.”3 Employers usually have more resources to pay damages than their employees do,4 and “in hard fact, the reason for the employers’ liability is the damages are taken from a deep pocket.”5

Determining potential responsibility

In Dr. R’s scenario, an adverse event follows the actions of a psychiatry resident who is performing a training activity at a hospital ER. Whether an attorney acting on behalf of an injured client can bring a claim of respondeat superior against the hospital, the resident’s academic institution, or the attending psychiatrist will depend on the nature of the relationships among these parties. This often becomes a complex legal matter that involves examining the residency program’s educational arrangements, official training documents (eg, affiliation agreements between a university and a hospital), employment contracts, and supervisory policies. In addition, statutes and legal precedents governing vicarious liability vary from state to state. Although an initial malpractice filing may name several individuals and institutions as defendants, courts eventually must apply their jurisdictions’ rules governing vicarious liability to determine which parties can lawfully bear potential liability.

Some courts have held that a private hospital generally is not responsible for negligent actions by attending physicians because the hospital does not control patient care decisions and physicians are not the hospital’s employees.6-8 Physicians in training, however, usually are employees of hospitals or their training institutions. Residents and attending physicians in many psychiatry training programs work at hospitals where patients reasonably believe that the doctors function as part of the hospital’s larger service enterprise. In some jurisdictions, this makes the hospitals potentially liable for their doctors’ acts,9 even when the doctors, as public employees, may have statutory immunity from being sued as individuals.10

Reuter11 has suggested that other agency theories may allow a resident’s error to create liability for an attending physician or medical school. The resident may be viewed as a “borrowed servant” such that, although a hospital was the resident’s general employer, the attending physician still exercised sufficient control with respect to the faulty act in question. A medical school faculty physician also may be liable along with the hospital under a joint employment theory based upon the faculty member’s “right to control” how the resident cares for the attending’s patient.11

Taking into account recent cases and trends in public expectations, Kachalia and Studdert12 suggest that potential liability of attending physicians rests on 2 factors: whether the treatment context and structure of supervisory obligations establishes a patient-physician relationship between the attending physician and the injured patient, and whether the attending physician has provided adequate supervision. Details of these 2 factors appear in Table 1.12-14

Independence vs oversight

Potential malpractice liability is one of many factors that postgraduate psychiatry programs consider when titrating the amount and intensity of supervision against letting residents make independent decisions and take on clinical responsibility for patients. Patients deserve good care and protection from mistakes that inexperienced physicians may make. At the same time, society recognizes that educating future physicians requires allowing residents to get real-world experiences in evaluating and treating patients.

These ideas are expressed in the “Program Requirements” for psychiatry residencies promulgated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).15 According to the ACGME, the “essential learning activity” that teaches physicians how to provide medical care is “interaction with patients under the guidance and supervision of faculty members” who let residents “exercise those skills with greater independence.”15

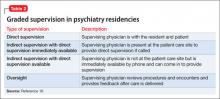

Psychiatry residencies must fashion learning experiences and supervisory schemes that give residents “graded and progressive responsibility” for providing care. Although each patient should have “an identifiable, appropriately-credentialed and privileged attending physician,” residents may provide substantial services under various levels of supervision described in Table 2.16

Deciding when and what kinds of patient care may be delegated to residents is the responsibility of residency program directors, who should base their judgments on explicit, prespecified criteria using information provided by supervising faculty members. Before letting first-year residents see patients on their own, psychiatry programs must determine that the residents can:

• take a history accurately

• do emergency psychiatric assessments

• present findings and data accurately to supervisors.

Physicians at all levels need to recognize when they should ask for help. The most important ACGME criterion for allowing a psychiatry resident to work under less stringent supervision is that the resident has demonstrated an “ability and willingness to ask for help when indicated.”16

Getting specifics

One way to respond Dr. R’s questions is to ask, “Do you know when you need help, and will you ask for it?” But her concerns deserve a more detailed (and more thoughtful) response that inquires about details of her training program and its specific educational experiences. Although it would be impossible to list everything to consider, some possible topics include:

• At what level of experience and training do residents assume this coverage responsibility?

• What kind of preparation do residents receive?

• What range of problems and conditions do the patients present?

• What level of clinical support is available on site—eg, experienced psychiatric nurses, other mental health staff, or other medical specialists?

• What has the program’s experience shown about residents’ actual readiness to handle these coverage duties?

• What guidelines have faculty members provided about when to call an attending physician or request a faculty member’s presence? Do these guidelines seem sound, given the above considerations?

Bottom Line

Psychiatry residents have supervisee relationships that create potential vicarious liability for institutions and faculty members. Residency training programs address these concerns by implementing adequate preparation for advanced responsibility, developing evaluative criteria and supervisory guidelines, and making sure that residents will ask for help when they need it.

Related Resources

- Regan JJ, Regan WM. Medical malpractice and respondeat superior. South Med J. 2002;95(5):545-548.

- Winrow B, Winrow AR. Personal protection: vicarious liability as applied to the various business structures. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008;53(2):146-149.

- Pozgar GD. Legal aspects of health care administration. 11th edition. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC; 2012.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Restatement of the law of agency. 3rd ed. §7.07(2). Philadelphia, PA: American Law Institute; 2006.

2. Baty T. Vicarious liability: a short history of the liability of employers, principals, partners, associations and trade-union members. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1916.

3. Dessauer v Memorial General Hosp, 628 P.2d 337 (N.M. 1981).

4. Firestone MH. Agency. In: Sandbar SS, Firestone MH, eds. Legal medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:43-47.

5. Dobbs D, Keeton RE, Owen DG. Prosser and Keaton on torts. 5th ed. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co; 1984.

6. Austin v Litvak, 682 P.2d 41 (Colo. 1984).

7. Kirk v Michael Reese Hospital and Medical Center, 513 N.E.2d 387 (Ill. 1987).

8. Gregg v National Medical Health Care Services, Inc., 499 P.2d 925 (Ariz. App. 1985).

9. Adamski v Tacoma General Hospital, 579 P.2d 970 (Wash. App. 1978).

10. Johnson v LeBonheur Children’s Medical Center, 74 S.W.3d 338 (Tenn. 2002).

11. Reuter SR. Professional liability in postgraduate medical education. Who is liable for resident negligence? J Leg Med. 1994;15(4):485-531.

12. Kachalia A, Studdert DM. Professional liability issues in graduate medical education. JAMA. 2004;292(9):1051-1056.

13. Lownsbury v VanBuren, 762 N.E.2d 354 (Ohio 2002).

14. Sterling v Johns Hopkins Hospital, 802 A.2d 440 (Md Ct Spec App 2002).

15. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Program and institutional guidelines. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/147/ProgramandInstitutional Guidelines/MedicalAccreditation/Psychiatry.aspx. Accessed April 8, 2013.

16. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in psychiatry. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/400_psychiatry_07012007_u04122008.pdf. Published July 1, 2007. Accessed April 8, 2013.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

In my residency program, we cover the psychiatric emergency room (ER) overnight, and we admit, discharge, and make treatment recommendations without calling the attending psychiatrists about every decision. But if something goes wrong—eg, a discharged patient later commits suicide—I’ve heard that the faculty psychiatrist may be held liable despite never having met the patient. Should we awaken our attendings to discuss every major treatment decision?

Submitted by “Dr. R”

Postgraduate medical training programs in all specialties let interns and residents make judgments and decisions outside the direct supervision of board-certified faculty members. Medical education cannot occur unless doctors learn to take independent responsibility for patients. But if poor decisions by physicians-in-training lead to bad outcomes, might their teachers and training institutions share the blame—and the legal liability for damages?

The answer is “yes.” To understand why, and to learn about how Dr. R’s residency program should address this possibility, we’ll cover:

• the theory of respondeat superior

• factors affecting potential vicarious liability

• how postgraduate training balances supervision needs with letting residents get real-world treatment experience.

Vicarious liability

In general, if Person A injures Person B, Person B may initiate a tort action against Person A to seek monetary compensation. If the injury occurred while Person A was working for Person C, then under a legal doctrine called respondeat superior (Latin for “let the master answer”), courts may allow Person B to sue Person C, too, even if Person C wasn’t present when the injury occurred and did nothing that harmed Person B directly.

Respondeat superior imposes vicarious liability on an employer for negligent acts by employees who are “performing work assigned by the employer or engaging in a course of conduct subject to the employer’s control.”1 The doctrine extends back to 17th-century English courts and originated under the theory that, during a servant’s employment, one may presume that the servant acted by his master’s authority.2

Modern authors state that the justification for imposing vicarious liability “is largely one of public or social policy under which it has been determined that, irrespective of fault, a party should be held to respond for the acts of another.”3 Employers usually have more resources to pay damages than their employees do,4 and “in hard fact, the reason for the employers’ liability is the damages are taken from a deep pocket.”5

Determining potential responsibility

In Dr. R’s scenario, an adverse event follows the actions of a psychiatry resident who is performing a training activity at a hospital ER. Whether an attorney acting on behalf of an injured client can bring a claim of respondeat superior against the hospital, the resident’s academic institution, or the attending psychiatrist will depend on the nature of the relationships among these parties. This often becomes a complex legal matter that involves examining the residency program’s educational arrangements, official training documents (eg, affiliation agreements between a university and a hospital), employment contracts, and supervisory policies. In addition, statutes and legal precedents governing vicarious liability vary from state to state. Although an initial malpractice filing may name several individuals and institutions as defendants, courts eventually must apply their jurisdictions’ rules governing vicarious liability to determine which parties can lawfully bear potential liability.

Some courts have held that a private hospital generally is not responsible for negligent actions by attending physicians because the hospital does not control patient care decisions and physicians are not the hospital’s employees.6-8 Physicians in training, however, usually are employees of hospitals or their training institutions. Residents and attending physicians in many psychiatry training programs work at hospitals where patients reasonably believe that the doctors function as part of the hospital’s larger service enterprise. In some jurisdictions, this makes the hospitals potentially liable for their doctors’ acts,9 even when the doctors, as public employees, may have statutory immunity from being sued as individuals.10

Reuter11 has suggested that other agency theories may allow a resident’s error to create liability for an attending physician or medical school. The resident may be viewed as a “borrowed servant” such that, although a hospital was the resident’s general employer, the attending physician still exercised sufficient control with respect to the faulty act in question. A medical school faculty physician also may be liable along with the hospital under a joint employment theory based upon the faculty member’s “right to control” how the resident cares for the attending’s patient.11

Taking into account recent cases and trends in public expectations, Kachalia and Studdert12 suggest that potential liability of attending physicians rests on 2 factors: whether the treatment context and structure of supervisory obligations establishes a patient-physician relationship between the attending physician and the injured patient, and whether the attending physician has provided adequate supervision. Details of these 2 factors appear in Table 1.12-14

Independence vs oversight

Potential malpractice liability is one of many factors that postgraduate psychiatry programs consider when titrating the amount and intensity of supervision against letting residents make independent decisions and take on clinical responsibility for patients. Patients deserve good care and protection from mistakes that inexperienced physicians may make. At the same time, society recognizes that educating future physicians requires allowing residents to get real-world experiences in evaluating and treating patients.

These ideas are expressed in the “Program Requirements” for psychiatry residencies promulgated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).15 According to the ACGME, the “essential learning activity” that teaches physicians how to provide medical care is “interaction with patients under the guidance and supervision of faculty members” who let residents “exercise those skills with greater independence.”15

Psychiatry residencies must fashion learning experiences and supervisory schemes that give residents “graded and progressive responsibility” for providing care. Although each patient should have “an identifiable, appropriately-credentialed and privileged attending physician,” residents may provide substantial services under various levels of supervision described in Table 2.16

Deciding when and what kinds of patient care may be delegated to residents is the responsibility of residency program directors, who should base their judgments on explicit, prespecified criteria using information provided by supervising faculty members. Before letting first-year residents see patients on their own, psychiatry programs must determine that the residents can:

• take a history accurately

• do emergency psychiatric assessments

• present findings and data accurately to supervisors.

Physicians at all levels need to recognize when they should ask for help. The most important ACGME criterion for allowing a psychiatry resident to work under less stringent supervision is that the resident has demonstrated an “ability and willingness to ask for help when indicated.”16

Getting specifics

One way to respond Dr. R’s questions is to ask, “Do you know when you need help, and will you ask for it?” But her concerns deserve a more detailed (and more thoughtful) response that inquires about details of her training program and its specific educational experiences. Although it would be impossible to list everything to consider, some possible topics include:

• At what level of experience and training do residents assume this coverage responsibility?

• What kind of preparation do residents receive?

• What range of problems and conditions do the patients present?

• What level of clinical support is available on site—eg, experienced psychiatric nurses, other mental health staff, or other medical specialists?

• What has the program’s experience shown about residents’ actual readiness to handle these coverage duties?

• What guidelines have faculty members provided about when to call an attending physician or request a faculty member’s presence? Do these guidelines seem sound, given the above considerations?

Bottom Line

Psychiatry residents have supervisee relationships that create potential vicarious liability for institutions and faculty members. Residency training programs address these concerns by implementing adequate preparation for advanced responsibility, developing evaluative criteria and supervisory guidelines, and making sure that residents will ask for help when they need it.

Related Resources

- Regan JJ, Regan WM. Medical malpractice and respondeat superior. South Med J. 2002;95(5):545-548.

- Winrow B, Winrow AR. Personal protection: vicarious liability as applied to the various business structures. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008;53(2):146-149.

- Pozgar GD. Legal aspects of health care administration. 11th edition. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC; 2012.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Restatement of the law of agency. 3rd ed. §7.07(2). Philadelphia, PA: American Law Institute; 2006.

2. Baty T. Vicarious liability: a short history of the liability of employers, principals, partners, associations and trade-union members. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1916.

3. Dessauer v Memorial General Hosp, 628 P.2d 337 (N.M. 1981).

4. Firestone MH. Agency. In: Sandbar SS, Firestone MH, eds. Legal medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:43-47.

5. Dobbs D, Keeton RE, Owen DG. Prosser and Keaton on torts. 5th ed. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co; 1984.

6. Austin v Litvak, 682 P.2d 41 (Colo. 1984).

7. Kirk v Michael Reese Hospital and Medical Center, 513 N.E.2d 387 (Ill. 1987).

8. Gregg v National Medical Health Care Services, Inc., 499 P.2d 925 (Ariz. App. 1985).

9. Adamski v Tacoma General Hospital, 579 P.2d 970 (Wash. App. 1978).

10. Johnson v LeBonheur Children’s Medical Center, 74 S.W.3d 338 (Tenn. 2002).

11. Reuter SR. Professional liability in postgraduate medical education. Who is liable for resident negligence? J Leg Med. 1994;15(4):485-531.

12. Kachalia A, Studdert DM. Professional liability issues in graduate medical education. JAMA. 2004;292(9):1051-1056.

13. Lownsbury v VanBuren, 762 N.E.2d 354 (Ohio 2002).

14. Sterling v Johns Hopkins Hospital, 802 A.2d 440 (Md Ct Spec App 2002).

15. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Program and institutional guidelines. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/147/ProgramandInstitutional Guidelines/MedicalAccreditation/Psychiatry.aspx. Accessed April 8, 2013.

16. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in psychiatry. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/400_psychiatry_07012007_u04122008.pdf. Published July 1, 2007. Accessed April 8, 2013.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

In my residency program, we cover the psychiatric emergency room (ER) overnight, and we admit, discharge, and make treatment recommendations without calling the attending psychiatrists about every decision. But if something goes wrong—eg, a discharged patient later commits suicide—I’ve heard that the faculty psychiatrist may be held liable despite never having met the patient. Should we awaken our attendings to discuss every major treatment decision?

Submitted by “Dr. R”

Postgraduate medical training programs in all specialties let interns and residents make judgments and decisions outside the direct supervision of board-certified faculty members. Medical education cannot occur unless doctors learn to take independent responsibility for patients. But if poor decisions by physicians-in-training lead to bad outcomes, might their teachers and training institutions share the blame—and the legal liability for damages?

The answer is “yes.” To understand why, and to learn about how Dr. R’s residency program should address this possibility, we’ll cover:

• the theory of respondeat superior

• factors affecting potential vicarious liability

• how postgraduate training balances supervision needs with letting residents get real-world treatment experience.

Vicarious liability

In general, if Person A injures Person B, Person B may initiate a tort action against Person A to seek monetary compensation. If the injury occurred while Person A was working for Person C, then under a legal doctrine called respondeat superior (Latin for “let the master answer”), courts may allow Person B to sue Person C, too, even if Person C wasn’t present when the injury occurred and did nothing that harmed Person B directly.

Respondeat superior imposes vicarious liability on an employer for negligent acts by employees who are “performing work assigned by the employer or engaging in a course of conduct subject to the employer’s control.”1 The doctrine extends back to 17th-century English courts and originated under the theory that, during a servant’s employment, one may presume that the servant acted by his master’s authority.2

Modern authors state that the justification for imposing vicarious liability “is largely one of public or social policy under which it has been determined that, irrespective of fault, a party should be held to respond for the acts of another.”3 Employers usually have more resources to pay damages than their employees do,4 and “in hard fact, the reason for the employers’ liability is the damages are taken from a deep pocket.”5

Determining potential responsibility

In Dr. R’s scenario, an adverse event follows the actions of a psychiatry resident who is performing a training activity at a hospital ER. Whether an attorney acting on behalf of an injured client can bring a claim of respondeat superior against the hospital, the resident’s academic institution, or the attending psychiatrist will depend on the nature of the relationships among these parties. This often becomes a complex legal matter that involves examining the residency program’s educational arrangements, official training documents (eg, affiliation agreements between a university and a hospital), employment contracts, and supervisory policies. In addition, statutes and legal precedents governing vicarious liability vary from state to state. Although an initial malpractice filing may name several individuals and institutions as defendants, courts eventually must apply their jurisdictions’ rules governing vicarious liability to determine which parties can lawfully bear potential liability.

Some courts have held that a private hospital generally is not responsible for negligent actions by attending physicians because the hospital does not control patient care decisions and physicians are not the hospital’s employees.6-8 Physicians in training, however, usually are employees of hospitals or their training institutions. Residents and attending physicians in many psychiatry training programs work at hospitals where patients reasonably believe that the doctors function as part of the hospital’s larger service enterprise. In some jurisdictions, this makes the hospitals potentially liable for their doctors’ acts,9 even when the doctors, as public employees, may have statutory immunity from being sued as individuals.10

Reuter11 has suggested that other agency theories may allow a resident’s error to create liability for an attending physician or medical school. The resident may be viewed as a “borrowed servant” such that, although a hospital was the resident’s general employer, the attending physician still exercised sufficient control with respect to the faulty act in question. A medical school faculty physician also may be liable along with the hospital under a joint employment theory based upon the faculty member’s “right to control” how the resident cares for the attending’s patient.11

Taking into account recent cases and trends in public expectations, Kachalia and Studdert12 suggest that potential liability of attending physicians rests on 2 factors: whether the treatment context and structure of supervisory obligations establishes a patient-physician relationship between the attending physician and the injured patient, and whether the attending physician has provided adequate supervision. Details of these 2 factors appear in Table 1.12-14

Independence vs oversight

Potential malpractice liability is one of many factors that postgraduate psychiatry programs consider when titrating the amount and intensity of supervision against letting residents make independent decisions and take on clinical responsibility for patients. Patients deserve good care and protection from mistakes that inexperienced physicians may make. At the same time, society recognizes that educating future physicians requires allowing residents to get real-world experiences in evaluating and treating patients.

These ideas are expressed in the “Program Requirements” for psychiatry residencies promulgated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).15 According to the ACGME, the “essential learning activity” that teaches physicians how to provide medical care is “interaction with patients under the guidance and supervision of faculty members” who let residents “exercise those skills with greater independence.”15

Psychiatry residencies must fashion learning experiences and supervisory schemes that give residents “graded and progressive responsibility” for providing care. Although each patient should have “an identifiable, appropriately-credentialed and privileged attending physician,” residents may provide substantial services under various levels of supervision described in Table 2.16

Deciding when and what kinds of patient care may be delegated to residents is the responsibility of residency program directors, who should base their judgments on explicit, prespecified criteria using information provided by supervising faculty members. Before letting first-year residents see patients on their own, psychiatry programs must determine that the residents can:

• take a history accurately

• do emergency psychiatric assessments

• present findings and data accurately to supervisors.

Physicians at all levels need to recognize when they should ask for help. The most important ACGME criterion for allowing a psychiatry resident to work under less stringent supervision is that the resident has demonstrated an “ability and willingness to ask for help when indicated.”16

Getting specifics

One way to respond Dr. R’s questions is to ask, “Do you know when you need help, and will you ask for it?” But her concerns deserve a more detailed (and more thoughtful) response that inquires about details of her training program and its specific educational experiences. Although it would be impossible to list everything to consider, some possible topics include:

• At what level of experience and training do residents assume this coverage responsibility?

• What kind of preparation do residents receive?

• What range of problems and conditions do the patients present?

• What level of clinical support is available on site—eg, experienced psychiatric nurses, other mental health staff, or other medical specialists?

• What has the program’s experience shown about residents’ actual readiness to handle these coverage duties?

• What guidelines have faculty members provided about when to call an attending physician or request a faculty member’s presence? Do these guidelines seem sound, given the above considerations?

Bottom Line

Psychiatry residents have supervisee relationships that create potential vicarious liability for institutions and faculty members. Residency training programs address these concerns by implementing adequate preparation for advanced responsibility, developing evaluative criteria and supervisory guidelines, and making sure that residents will ask for help when they need it.

Related Resources

- Regan JJ, Regan WM. Medical malpractice and respondeat superior. South Med J. 2002;95(5):545-548.

- Winrow B, Winrow AR. Personal protection: vicarious liability as applied to the various business structures. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008;53(2):146-149.

- Pozgar GD. Legal aspects of health care administration. 11th edition. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC; 2012.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Restatement of the law of agency. 3rd ed. §7.07(2). Philadelphia, PA: American Law Institute; 2006.

2. Baty T. Vicarious liability: a short history of the liability of employers, principals, partners, associations and trade-union members. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1916.

3. Dessauer v Memorial General Hosp, 628 P.2d 337 (N.M. 1981).

4. Firestone MH. Agency. In: Sandbar SS, Firestone MH, eds. Legal medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:43-47.

5. Dobbs D, Keeton RE, Owen DG. Prosser and Keaton on torts. 5th ed. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co; 1984.

6. Austin v Litvak, 682 P.2d 41 (Colo. 1984).

7. Kirk v Michael Reese Hospital and Medical Center, 513 N.E.2d 387 (Ill. 1987).

8. Gregg v National Medical Health Care Services, Inc., 499 P.2d 925 (Ariz. App. 1985).

9. Adamski v Tacoma General Hospital, 579 P.2d 970 (Wash. App. 1978).

10. Johnson v LeBonheur Children’s Medical Center, 74 S.W.3d 338 (Tenn. 2002).

11. Reuter SR. Professional liability in postgraduate medical education. Who is liable for resident negligence? J Leg Med. 1994;15(4):485-531.

12. Kachalia A, Studdert DM. Professional liability issues in graduate medical education. JAMA. 2004;292(9):1051-1056.

13. Lownsbury v VanBuren, 762 N.E.2d 354 (Ohio 2002).

14. Sterling v Johns Hopkins Hospital, 802 A.2d 440 (Md Ct Spec App 2002).

15. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Program and institutional guidelines. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/147/ProgramandInstitutional Guidelines/MedicalAccreditation/Psychiatry.aspx. Accessed April 8, 2013.

16. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in psychiatry. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/400_psychiatry_07012007_u04122008.pdf. Published July 1, 2007. Accessed April 8, 2013.