User login

In studies of schizophrenia, one of the more striking findings is the delay in the initiation of treatment. That delay ranges from 1 to 2 years for patients experiencing psychotic symptoms to several years if the prodromal phase is taken into account.1 Yet duration of untreated psychosis has been found to be a critical factor in prognosis, including psychosocial functioning, in patients with schizophrenia.2,3 Identification of individuals in the prodromal phase not only offers an opportunity to intervene at an earlier symptomatic stage, but might be associated with a better response to antipsychotics and a better overall treatment outcome as well.

What’s in a name?

Several terms, including ultra high risk, clinical high risk, at-risk mental state, psychosis risk syndrome, and schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome, have been used to describe the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. The proposal to include attenuated psychosis syndrome (APS) in the DSM-5—originally intended to capture those with subthreshold delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized behavior, occurring at least once a week for the past month and worsening over the past year—generated a debate about the validity of such a diagnostic category4,5 that culminated in the inclusion of APS as a condition for further study but not as a term for clinical use.6 Its presence in the DSM-5 brings to the forefront the importance of early clinical intervention in patients at risk of developing psychotic illness.

Schizophrenia is not inevitable

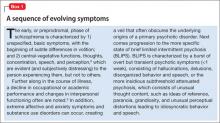

The prodromal phase can be viewed as a sequence of evolving symptoms7 (Box 18,9), starting with subtle differences evident only to the person experiencing them and often progressing to brief limited intermittent psychosis (BLIPS) or attenuated psychosis.8

In fact, prodrome is a retrospective diagnosis. The predictive power of conversion to psychosis has been found to fluctuate from as low as 9% to as high as 76%,10 prompting ethical concerns about a high false-positive rate, the assumption of inevitability associated with the term “schizophrenia prodrome,”9 and the potential for overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis. Concerns about psychosocial stigma and exposure to antipsychotic medications have been expressed as well.11

A case for early engagement

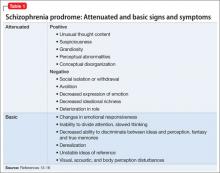

In retrospect, patients who eventually progress to psychotic illness are commonly found to have been in the prodromal phase for several years. Yet many patients’ first contact with psychiatric services occurs during a florid episode of acute psychosis. Identifying patients in the early prodromal period offers the opportunity to more effectively engage them and form a therapeutic alliance.12 Any young adult who presents with a decline in academic or occupational function, social withdrawal, perplexity, and apparent distress or agitation (Table 113-16) without a clear precipitating factor should therefore be closely monitored, particularly if he (she) has a family history of psychosis.

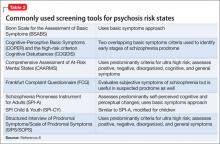

Screening tools. A variety of interviews and rating scales (Table 28) have been developed to assess and monitor at-risk persons, a number of which have been designed to detect basic symptoms in the early phase of prodrome. In addition to the structured scales, several self-report tools—including the Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief (PQ-B), Youth Psychosis At Risk Questionnaire-Brief (YPARQ-B), Prime Screen-Revised, and PROD-screen (Screen for prodromal symptoms of psychosis)—have been found to be useful in screening a large sample to identify those who might need further evaluation.17

Increased risk of conversion. Several clinical factors are associated with an increased risk of conversion to psychotic illness.9 In addition to family history, these include:

• greater severity and longer duration of attenuated positive symptoms

• presence of bizarre thoughts and behavior

• paranoia

• decline in global assessment of functioning score over the previous year

• use of either Cannabis or amphetamines.

A history of childhood trauma, increased sensitivity to psychosocial stressors, and dysregulation of the hypothalamicpituitary axis also have been associated with progression to psychosis.18

Recent evidence suggests that the prodromal phase is a predictor not only for psychosis but also for other disabling psychiatric illnesses, such as bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.19

From a phenomenological standpoint, disturbance of the sense of self—characterized by features such as depersonalization, derealization, decreased reactivity to other people and the environment, and intense reflectivity to oneself or others—has been proposed as a critical marker for progression to psychosis.20 Another predictor is the perception of negativity of others toward oneself. Examples include heightened sensitivity to rejection or shame, which seems to emerge from a pattern of insecure attachment, and the outsider status experienced by immigrants faced with multiple social, cultural, and language barriers.21 The presence of obsessivecompulsive symptoms during the prodromal phase has been linked to significant impairment in functioning, an acute switch to psychosis, and an increased risk of suicide.22

Monitor or treat? An optimal approach

A key dilemma in the management of patients who exhibit signs and symptoms of schizophrenia prodrome is whether to simply monitor closely or to initiate treatment.

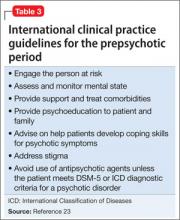

International clinical practice guidelines recommend several practical steps in the monitoring of patients in a prepsychotic state (Table 3),23 but caution against the use of antipsychotic agents unless the patient meets diagnostic criteria for a psychotic disorder.

CBT. Some evidence supports the initiation of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) during the initial prodromal phase and the addition of alow-dose atypical antipsychotic if the patient progresses to a later phase, characterized by BLIPS/APS.24,25 Evidence also suggests that a combination of CBT and antipsychotic medication might delay, but not prevent, the progression to a psychotic episode.9 Any risk of adverse metabolic complications precludes use ofan atypical antipsychotic.One potential alternative is the use of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (Box 2).26,27

A clinically useful approach would be to view schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome not as a distinct diagnostic category but as a cluster of signs and symptoms associated with an increased risk of psychosis, with persons in this phase in need of close follow-up and, possibly, early initiation of an antipsychotic agent. It is important to engage the patient and his family at an early stage to educate them about the diagnostic uncertainty; to help them deal with the stigma; to manage risk factors; and, collaboratively, to decide on an intervention strategy.23,28

Bottom Line

Despite several drawbacks, the concept of schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome may

be viewed as a cluster of signs and symptoms (rather than a distinct diagnostic category) associated with increased risk for psychosis that need close follow up. Follow up may involve psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic interventions and, need be, early initiation of antipsychotics. In addition, such symptoms may be associated with other psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder and obsessive- compulsive disorder. Timely attention and early intervention may alter the course

and improve overall prognosis.

Related Resources

• Early intervention in psychosis. WPA Education Committee’s recommended roles of the psychiatrist. www.wpanet.org/uploads/Education/Educational_Resources/earlyintervention-psychosis.pdf.

• Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre, Melbourne, Australia. http://eppic.org.au/psychosis.

• International Early Psychosis Association Writing Group. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:s120-124. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/187/48/s120.full.

Disclosures

Dr. Madaan is an employee of University of Virginia Health System. As an employee with the University of Virginia, Dr. Madaan has received research support from Eli Lilly and Company, Forest, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Shire, and Sunovion. He also has served as a consultant for the NOW Coalition for Bipolar Disorder, and on the American Psychiatric Association’s Focus Self-Assessment editorial board. Drs. Bestha and Kolli report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Salokangas RK, McGlashan TH. Early detection and intervention of psychosis. A review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008;62:92-105.

2. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10): 1785-1804.

3. Stefanopoulou E, Lafuente AR, Fonseca AS, et al. Global assessment of psychosocial functioning and predictors of outcome in schizophrenia. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2011;15(1):62-68.

4. Yung AR, Nelson B, Thompson AD, et al. Should a “Risk Syndrome for Psychosis” be included in the DSMV? Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):7-15.

5. Corcoran CM, First MB, Cornblatt B. The psychosis risk syndrome and its proposed inclusion in the DSM-V: a risk-benefit analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):16-22.

6. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

7. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Berning J, et al. Basic symptoms and ultrahigh risk criteria: symptom development in the initial prodromal state. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):182-191.

8. Correll CU, Hauser M, Auther AM, et al. Research in people with psychosis risk syndrome: a review of the current evidence and future directions. J Child Psychol

Psychiatry. 2010;51(4):390-431.

9. Addington J, Heinssen R. Prediction and prevention of psychosis in youth at clinical high risk. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:269-289.

10. Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(1):28-37.

11. Singh F, Mirzakhanian H, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Ethical implications for clinical practice and future research in “at risk” individuals. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):606-612.

12. Bota RG, Munro JS, Ricci WF, et al. The dynamics of insight in the prodrome of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(5):355-362.

13. Phillips LJ, Yung AR, McGorry PD. Identification of young people at risk of psychosis: validation of Personal Assessment and Crisis Evaluation Clinic intake criteria. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(suppl):S164-S169.

14. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Woods SW, et al. Symptom assessment in schizophrenic prodromal states. Psychiatr Q. 1999;70(4):273-287.

15. Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J, Picker H. Predicting first-episode psychosis by basic symptom criteria. Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2007;4(1):11-22.

16. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Picker H, et al. Basic symptoms in early psychotic and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;51:s31-s37.

17. Kline E, Wilson C, Ereshefsky S, et al. Convergent and discriminant validity of attenuated psychosis screening tools. Schizophr Res. 2012;134(1):49-53.

18. Holtzman CW, Shapiro DI, Trotman HD, et al. Stress and the prodromal phase of psychosis. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):527-533.

19. Rössler W, Hengartner MP, Ajdacic-Gross V, et al. Subclinical psychosis symptoms in young adults are risk factors for subsequent common mental disorders. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):18-23.

20. Nelson B, Yung AR, Bechdolf A, et al. The phenomenological critique and self-disturbance: implications for ultra-high risk (“prodrome”) research. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(2):381-392.

21. Salokangas RK, Heinimaa M, Svirskis T, et al. Perceived negative attitude of others as an early sign of psychosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(4):233-238.

22. Niendam TA, Berzak J, Cannon TD, et al. Obsessive compulsive symptoms in the psychosis prodrome:correlates of clinical and functional outcome. Schizophr

Res. 2009;108(1-3):170-175.

23. Addington J, Amminger GP, Barbato A. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:s120-s124.

24. Klosterkötter J, Schultze-Lutter F, Bechdolf A, et al. Prediction and prevention of schizophrenia: what has been achieved and where to go next? World Psychiatry.

2011;10(3):165-174.

25. Stafford MR, Jackson H, Mayo-Wilson E, et al. Early interventions to prevent psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f185.

In studies of schizophrenia, one of the more striking findings is the delay in the initiation of treatment. That delay ranges from 1 to 2 years for patients experiencing psychotic symptoms to several years if the prodromal phase is taken into account.1 Yet duration of untreated psychosis has been found to be a critical factor in prognosis, including psychosocial functioning, in patients with schizophrenia.2,3 Identification of individuals in the prodromal phase not only offers an opportunity to intervene at an earlier symptomatic stage, but might be associated with a better response to antipsychotics and a better overall treatment outcome as well.

What’s in a name?

Several terms, including ultra high risk, clinical high risk, at-risk mental state, psychosis risk syndrome, and schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome, have been used to describe the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. The proposal to include attenuated psychosis syndrome (APS) in the DSM-5—originally intended to capture those with subthreshold delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized behavior, occurring at least once a week for the past month and worsening over the past year—generated a debate about the validity of such a diagnostic category4,5 that culminated in the inclusion of APS as a condition for further study but not as a term for clinical use.6 Its presence in the DSM-5 brings to the forefront the importance of early clinical intervention in patients at risk of developing psychotic illness.

Schizophrenia is not inevitable

The prodromal phase can be viewed as a sequence of evolving symptoms7 (Box 18,9), starting with subtle differences evident only to the person experiencing them and often progressing to brief limited intermittent psychosis (BLIPS) or attenuated psychosis.8

In fact, prodrome is a retrospective diagnosis. The predictive power of conversion to psychosis has been found to fluctuate from as low as 9% to as high as 76%,10 prompting ethical concerns about a high false-positive rate, the assumption of inevitability associated with the term “schizophrenia prodrome,”9 and the potential for overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis. Concerns about psychosocial stigma and exposure to antipsychotic medications have been expressed as well.11

A case for early engagement

In retrospect, patients who eventually progress to psychotic illness are commonly found to have been in the prodromal phase for several years. Yet many patients’ first contact with psychiatric services occurs during a florid episode of acute psychosis. Identifying patients in the early prodromal period offers the opportunity to more effectively engage them and form a therapeutic alliance.12 Any young adult who presents with a decline in academic or occupational function, social withdrawal, perplexity, and apparent distress or agitation (Table 113-16) without a clear precipitating factor should therefore be closely monitored, particularly if he (she) has a family history of psychosis.

Screening tools. A variety of interviews and rating scales (Table 28) have been developed to assess and monitor at-risk persons, a number of which have been designed to detect basic symptoms in the early phase of prodrome. In addition to the structured scales, several self-report tools—including the Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief (PQ-B), Youth Psychosis At Risk Questionnaire-Brief (YPARQ-B), Prime Screen-Revised, and PROD-screen (Screen for prodromal symptoms of psychosis)—have been found to be useful in screening a large sample to identify those who might need further evaluation.17

Increased risk of conversion. Several clinical factors are associated with an increased risk of conversion to psychotic illness.9 In addition to family history, these include:

• greater severity and longer duration of attenuated positive symptoms

• presence of bizarre thoughts and behavior

• paranoia

• decline in global assessment of functioning score over the previous year

• use of either Cannabis or amphetamines.

A history of childhood trauma, increased sensitivity to psychosocial stressors, and dysregulation of the hypothalamicpituitary axis also have been associated with progression to psychosis.18

Recent evidence suggests that the prodromal phase is a predictor not only for psychosis but also for other disabling psychiatric illnesses, such as bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.19

From a phenomenological standpoint, disturbance of the sense of self—characterized by features such as depersonalization, derealization, decreased reactivity to other people and the environment, and intense reflectivity to oneself or others—has been proposed as a critical marker for progression to psychosis.20 Another predictor is the perception of negativity of others toward oneself. Examples include heightened sensitivity to rejection or shame, which seems to emerge from a pattern of insecure attachment, and the outsider status experienced by immigrants faced with multiple social, cultural, and language barriers.21 The presence of obsessivecompulsive symptoms during the prodromal phase has been linked to significant impairment in functioning, an acute switch to psychosis, and an increased risk of suicide.22

Monitor or treat? An optimal approach

A key dilemma in the management of patients who exhibit signs and symptoms of schizophrenia prodrome is whether to simply monitor closely or to initiate treatment.

International clinical practice guidelines recommend several practical steps in the monitoring of patients in a prepsychotic state (Table 3),23 but caution against the use of antipsychotic agents unless the patient meets diagnostic criteria for a psychotic disorder.

CBT. Some evidence supports the initiation of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) during the initial prodromal phase and the addition of alow-dose atypical antipsychotic if the patient progresses to a later phase, characterized by BLIPS/APS.24,25 Evidence also suggests that a combination of CBT and antipsychotic medication might delay, but not prevent, the progression to a psychotic episode.9 Any risk of adverse metabolic complications precludes use ofan atypical antipsychotic.One potential alternative is the use of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (Box 2).26,27

A clinically useful approach would be to view schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome not as a distinct diagnostic category but as a cluster of signs and symptoms associated with an increased risk of psychosis, with persons in this phase in need of close follow-up and, possibly, early initiation of an antipsychotic agent. It is important to engage the patient and his family at an early stage to educate them about the diagnostic uncertainty; to help them deal with the stigma; to manage risk factors; and, collaboratively, to decide on an intervention strategy.23,28

Bottom Line

Despite several drawbacks, the concept of schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome may

be viewed as a cluster of signs and symptoms (rather than a distinct diagnostic category) associated with increased risk for psychosis that need close follow up. Follow up may involve psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic interventions and, need be, early initiation of antipsychotics. In addition, such symptoms may be associated with other psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder and obsessive- compulsive disorder. Timely attention and early intervention may alter the course

and improve overall prognosis.

Related Resources

• Early intervention in psychosis. WPA Education Committee’s recommended roles of the psychiatrist. www.wpanet.org/uploads/Education/Educational_Resources/earlyintervention-psychosis.pdf.

• Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre, Melbourne, Australia. http://eppic.org.au/psychosis.

• International Early Psychosis Association Writing Group. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:s120-124. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/187/48/s120.full.

Disclosures

Dr. Madaan is an employee of University of Virginia Health System. As an employee with the University of Virginia, Dr. Madaan has received research support from Eli Lilly and Company, Forest, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Shire, and Sunovion. He also has served as a consultant for the NOW Coalition for Bipolar Disorder, and on the American Psychiatric Association’s Focus Self-Assessment editorial board. Drs. Bestha and Kolli report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

In studies of schizophrenia, one of the more striking findings is the delay in the initiation of treatment. That delay ranges from 1 to 2 years for patients experiencing psychotic symptoms to several years if the prodromal phase is taken into account.1 Yet duration of untreated psychosis has been found to be a critical factor in prognosis, including psychosocial functioning, in patients with schizophrenia.2,3 Identification of individuals in the prodromal phase not only offers an opportunity to intervene at an earlier symptomatic stage, but might be associated with a better response to antipsychotics and a better overall treatment outcome as well.

What’s in a name?

Several terms, including ultra high risk, clinical high risk, at-risk mental state, psychosis risk syndrome, and schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome, have been used to describe the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. The proposal to include attenuated psychosis syndrome (APS) in the DSM-5—originally intended to capture those with subthreshold delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized behavior, occurring at least once a week for the past month and worsening over the past year—generated a debate about the validity of such a diagnostic category4,5 that culminated in the inclusion of APS as a condition for further study but not as a term for clinical use.6 Its presence in the DSM-5 brings to the forefront the importance of early clinical intervention in patients at risk of developing psychotic illness.

Schizophrenia is not inevitable

The prodromal phase can be viewed as a sequence of evolving symptoms7 (Box 18,9), starting with subtle differences evident only to the person experiencing them and often progressing to brief limited intermittent psychosis (BLIPS) or attenuated psychosis.8

In fact, prodrome is a retrospective diagnosis. The predictive power of conversion to psychosis has been found to fluctuate from as low as 9% to as high as 76%,10 prompting ethical concerns about a high false-positive rate, the assumption of inevitability associated with the term “schizophrenia prodrome,”9 and the potential for overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis. Concerns about psychosocial stigma and exposure to antipsychotic medications have been expressed as well.11

A case for early engagement

In retrospect, patients who eventually progress to psychotic illness are commonly found to have been in the prodromal phase for several years. Yet many patients’ first contact with psychiatric services occurs during a florid episode of acute psychosis. Identifying patients in the early prodromal period offers the opportunity to more effectively engage them and form a therapeutic alliance.12 Any young adult who presents with a decline in academic or occupational function, social withdrawal, perplexity, and apparent distress or agitation (Table 113-16) without a clear precipitating factor should therefore be closely monitored, particularly if he (she) has a family history of psychosis.

Screening tools. A variety of interviews and rating scales (Table 28) have been developed to assess and monitor at-risk persons, a number of which have been designed to detect basic symptoms in the early phase of prodrome. In addition to the structured scales, several self-report tools—including the Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief (PQ-B), Youth Psychosis At Risk Questionnaire-Brief (YPARQ-B), Prime Screen-Revised, and PROD-screen (Screen for prodromal symptoms of psychosis)—have been found to be useful in screening a large sample to identify those who might need further evaluation.17

Increased risk of conversion. Several clinical factors are associated with an increased risk of conversion to psychotic illness.9 In addition to family history, these include:

• greater severity and longer duration of attenuated positive symptoms

• presence of bizarre thoughts and behavior

• paranoia

• decline in global assessment of functioning score over the previous year

• use of either Cannabis or amphetamines.

A history of childhood trauma, increased sensitivity to psychosocial stressors, and dysregulation of the hypothalamicpituitary axis also have been associated with progression to psychosis.18

Recent evidence suggests that the prodromal phase is a predictor not only for psychosis but also for other disabling psychiatric illnesses, such as bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.19

From a phenomenological standpoint, disturbance of the sense of self—characterized by features such as depersonalization, derealization, decreased reactivity to other people and the environment, and intense reflectivity to oneself or others—has been proposed as a critical marker for progression to psychosis.20 Another predictor is the perception of negativity of others toward oneself. Examples include heightened sensitivity to rejection or shame, which seems to emerge from a pattern of insecure attachment, and the outsider status experienced by immigrants faced with multiple social, cultural, and language barriers.21 The presence of obsessivecompulsive symptoms during the prodromal phase has been linked to significant impairment in functioning, an acute switch to psychosis, and an increased risk of suicide.22

Monitor or treat? An optimal approach

A key dilemma in the management of patients who exhibit signs and symptoms of schizophrenia prodrome is whether to simply monitor closely or to initiate treatment.

International clinical practice guidelines recommend several practical steps in the monitoring of patients in a prepsychotic state (Table 3),23 but caution against the use of antipsychotic agents unless the patient meets diagnostic criteria for a psychotic disorder.

CBT. Some evidence supports the initiation of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) during the initial prodromal phase and the addition of alow-dose atypical antipsychotic if the patient progresses to a later phase, characterized by BLIPS/APS.24,25 Evidence also suggests that a combination of CBT and antipsychotic medication might delay, but not prevent, the progression to a psychotic episode.9 Any risk of adverse metabolic complications precludes use ofan atypical antipsychotic.One potential alternative is the use of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (Box 2).26,27

A clinically useful approach would be to view schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome not as a distinct diagnostic category but as a cluster of signs and symptoms associated with an increased risk of psychosis, with persons in this phase in need of close follow-up and, possibly, early initiation of an antipsychotic agent. It is important to engage the patient and his family at an early stage to educate them about the diagnostic uncertainty; to help them deal with the stigma; to manage risk factors; and, collaboratively, to decide on an intervention strategy.23,28

Bottom Line

Despite several drawbacks, the concept of schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome may

be viewed as a cluster of signs and symptoms (rather than a distinct diagnostic category) associated with increased risk for psychosis that need close follow up. Follow up may involve psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic interventions and, need be, early initiation of antipsychotics. In addition, such symptoms may be associated with other psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder and obsessive- compulsive disorder. Timely attention and early intervention may alter the course

and improve overall prognosis.

Related Resources

• Early intervention in psychosis. WPA Education Committee’s recommended roles of the psychiatrist. www.wpanet.org/uploads/Education/Educational_Resources/earlyintervention-psychosis.pdf.

• Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre, Melbourne, Australia. http://eppic.org.au/psychosis.

• International Early Psychosis Association Writing Group. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:s120-124. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/187/48/s120.full.

Disclosures

Dr. Madaan is an employee of University of Virginia Health System. As an employee with the University of Virginia, Dr. Madaan has received research support from Eli Lilly and Company, Forest, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Shire, and Sunovion. He also has served as a consultant for the NOW Coalition for Bipolar Disorder, and on the American Psychiatric Association’s Focus Self-Assessment editorial board. Drs. Bestha and Kolli report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Salokangas RK, McGlashan TH. Early detection and intervention of psychosis. A review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008;62:92-105.

2. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10): 1785-1804.

3. Stefanopoulou E, Lafuente AR, Fonseca AS, et al. Global assessment of psychosocial functioning and predictors of outcome in schizophrenia. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2011;15(1):62-68.

4. Yung AR, Nelson B, Thompson AD, et al. Should a “Risk Syndrome for Psychosis” be included in the DSMV? Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):7-15.

5. Corcoran CM, First MB, Cornblatt B. The psychosis risk syndrome and its proposed inclusion in the DSM-V: a risk-benefit analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):16-22.

6. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

7. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Berning J, et al. Basic symptoms and ultrahigh risk criteria: symptom development in the initial prodromal state. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):182-191.

8. Correll CU, Hauser M, Auther AM, et al. Research in people with psychosis risk syndrome: a review of the current evidence and future directions. J Child Psychol

Psychiatry. 2010;51(4):390-431.

9. Addington J, Heinssen R. Prediction and prevention of psychosis in youth at clinical high risk. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:269-289.

10. Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(1):28-37.

11. Singh F, Mirzakhanian H, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Ethical implications for clinical practice and future research in “at risk” individuals. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):606-612.

12. Bota RG, Munro JS, Ricci WF, et al. The dynamics of insight in the prodrome of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(5):355-362.

13. Phillips LJ, Yung AR, McGorry PD. Identification of young people at risk of psychosis: validation of Personal Assessment and Crisis Evaluation Clinic intake criteria. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(suppl):S164-S169.

14. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Woods SW, et al. Symptom assessment in schizophrenic prodromal states. Psychiatr Q. 1999;70(4):273-287.

15. Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J, Picker H. Predicting first-episode psychosis by basic symptom criteria. Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2007;4(1):11-22.

16. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Picker H, et al. Basic symptoms in early psychotic and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;51:s31-s37.

17. Kline E, Wilson C, Ereshefsky S, et al. Convergent and discriminant validity of attenuated psychosis screening tools. Schizophr Res. 2012;134(1):49-53.

18. Holtzman CW, Shapiro DI, Trotman HD, et al. Stress and the prodromal phase of psychosis. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):527-533.

19. Rössler W, Hengartner MP, Ajdacic-Gross V, et al. Subclinical psychosis symptoms in young adults are risk factors for subsequent common mental disorders. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):18-23.

20. Nelson B, Yung AR, Bechdolf A, et al. The phenomenological critique and self-disturbance: implications for ultra-high risk (“prodrome”) research. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(2):381-392.

21. Salokangas RK, Heinimaa M, Svirskis T, et al. Perceived negative attitude of others as an early sign of psychosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(4):233-238.

22. Niendam TA, Berzak J, Cannon TD, et al. Obsessive compulsive symptoms in the psychosis prodrome:correlates of clinical and functional outcome. Schizophr

Res. 2009;108(1-3):170-175.

23. Addington J, Amminger GP, Barbato A. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:s120-s124.

24. Klosterkötter J, Schultze-Lutter F, Bechdolf A, et al. Prediction and prevention of schizophrenia: what has been achieved and where to go next? World Psychiatry.

2011;10(3):165-174.

25. Stafford MR, Jackson H, Mayo-Wilson E, et al. Early interventions to prevent psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f185.

1. Salokangas RK, McGlashan TH. Early detection and intervention of psychosis. A review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008;62:92-105.

2. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10): 1785-1804.

3. Stefanopoulou E, Lafuente AR, Fonseca AS, et al. Global assessment of psychosocial functioning and predictors of outcome in schizophrenia. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2011;15(1):62-68.

4. Yung AR, Nelson B, Thompson AD, et al. Should a “Risk Syndrome for Psychosis” be included in the DSMV? Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):7-15.

5. Corcoran CM, First MB, Cornblatt B. The psychosis risk syndrome and its proposed inclusion in the DSM-V: a risk-benefit analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):16-22.

6. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

7. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Berning J, et al. Basic symptoms and ultrahigh risk criteria: symptom development in the initial prodromal state. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):182-191.

8. Correll CU, Hauser M, Auther AM, et al. Research in people with psychosis risk syndrome: a review of the current evidence and future directions. J Child Psychol

Psychiatry. 2010;51(4):390-431.

9. Addington J, Heinssen R. Prediction and prevention of psychosis in youth at clinical high risk. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:269-289.

10. Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(1):28-37.

11. Singh F, Mirzakhanian H, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Ethical implications for clinical practice and future research in “at risk” individuals. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):606-612.

12. Bota RG, Munro JS, Ricci WF, et al. The dynamics of insight in the prodrome of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(5):355-362.

13. Phillips LJ, Yung AR, McGorry PD. Identification of young people at risk of psychosis: validation of Personal Assessment and Crisis Evaluation Clinic intake criteria. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(suppl):S164-S169.

14. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Woods SW, et al. Symptom assessment in schizophrenic prodromal states. Psychiatr Q. 1999;70(4):273-287.

15. Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J, Picker H. Predicting first-episode psychosis by basic symptom criteria. Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2007;4(1):11-22.

16. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Picker H, et al. Basic symptoms in early psychotic and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;51:s31-s37.

17. Kline E, Wilson C, Ereshefsky S, et al. Convergent and discriminant validity of attenuated psychosis screening tools. Schizophr Res. 2012;134(1):49-53.

18. Holtzman CW, Shapiro DI, Trotman HD, et al. Stress and the prodromal phase of psychosis. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):527-533.

19. Rössler W, Hengartner MP, Ajdacic-Gross V, et al. Subclinical psychosis symptoms in young adults are risk factors for subsequent common mental disorders. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):18-23.

20. Nelson B, Yung AR, Bechdolf A, et al. The phenomenological critique and self-disturbance: implications for ultra-high risk (“prodrome”) research. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(2):381-392.

21. Salokangas RK, Heinimaa M, Svirskis T, et al. Perceived negative attitude of others as an early sign of psychosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(4):233-238.

22. Niendam TA, Berzak J, Cannon TD, et al. Obsessive compulsive symptoms in the psychosis prodrome:correlates of clinical and functional outcome. Schizophr

Res. 2009;108(1-3):170-175.

23. Addington J, Amminger GP, Barbato A. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:s120-s124.

24. Klosterkötter J, Schultze-Lutter F, Bechdolf A, et al. Prediction and prevention of schizophrenia: what has been achieved and where to go next? World Psychiatry.

2011;10(3):165-174.

25. Stafford MR, Jackson H, Mayo-Wilson E, et al. Early interventions to prevent psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f185.