User login

6 ‘M’s to keep in mind when you next see a patient with anorexia nervosa

Anorexia nervosa is associated with comorbid psychiatric disorders, severe physical complications, and high mortality. To help you remember important clinical information when working with patients with anorexia, we propose this “6 M” model for screening, treatment, and prognosis.

Monitor closely. Anorexia can go undiagnosed and untreated for years. During your patients’ office visits, ask about body image, exercise habits, and menstrual irregularities, especially when seeing at-risk youth. During physical examination, reluctance to be weighed, vital sign abnormalities (eg, orthostatic hypotension, variability in pulse), skin abnormalities (lanugo hair, dryness), and marks indicating self-harm can serve as diagnostic indicators. Consider hospitalization for patients at <75% of their ideal body weight, who refuse to eat, or who show vital signs and laboratory abnormalities.

Media. By providing information on healthy eating and nutrition, the Internet can be an excellent resource for people with an eating disorder; however, you should also be aware of the impact of so-called pro-ana Web sites. People with anorexia use these Web sites to discuss their illness, but the sites sometimes glorify eating disorders as a lifestyle choice, and can be a place to share tips and tricks on extreme dieting, and might promote what is known as “thinspiration” in popular culture.

Meals. The American Dietetic Association recommends that anorexic patients begin oral intake at no more than 30 to 40 kcal/kg/day, and then gradually increase it, with a weight gain goal of 0.5 to 1 lb per week.

This graduated weight gain is done to prevent refeeding syndrome. After chronic starvation, intracellular phosphate stores are depleted and once carbohydrate intake resumes, insulin release causes phosphate to enter cells, thereby leading to hypophosphatemia. This electrolyte abnormality can result in cardiac failure. As a result, consider regular monitoring of phosphate levels, especially during the first week of reintroducing food.

Multimodal therapy. Despite being notoriously difficult to treat, patients with anorexia might respond to psychotherapy—especially family therapy—with an increased remission rate and faster return to health, compared with other forms of treatment. With a multimodal regimen involving proper refeeding techniques, family therapy, and medications as appropriate, recovery is possible.

Medications might be a helpful adjunct in patients who do not gain weight despite psychotherapy and proper nutritional measures. For example:

• There is some research on medications such as olanzapine and anxiolytics for treating anorexia.

• A low-dose anxiolytic might benefit patients with preprandial anxiety.

• Comorbid psychiatric disorders might improve during treatment of the eating disorder.

• Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and second-generation antipsychotics might help manage severe comorbid psychiatric disorders.

Because of low body weight and altered plasma protein binding, start medications at a low dosage. The risk of adverse effects can increase because more “free” medication is available. Consider avoiding medications such as bupropion and tricyclic antidepressants, because they carry an increased risk of seizures and cardiac effects, respectively.

Morbidity and mortality. Untreated anorexia has the highest mortality among psychiatric disorders: approximately 5.1 deaths for every 1,000 people.1 Recent meta-analyses show that patients with anorexia may have a 5.86 times greater risk of death than the general population.1 Serious sequelae include cardiac complications; osteoporosis; infertility; and comorbid psychiatric conditions such as substance abuse, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.2

1. Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, et al. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011; 68(7):724-731.

2. Yager J, Andersen AE. Clinical practice. Anorexia nervosa. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(14):1481-1488.

Anorexia nervosa is associated with comorbid psychiatric disorders, severe physical complications, and high mortality. To help you remember important clinical information when working with patients with anorexia, we propose this “6 M” model for screening, treatment, and prognosis.

Monitor closely. Anorexia can go undiagnosed and untreated for years. During your patients’ office visits, ask about body image, exercise habits, and menstrual irregularities, especially when seeing at-risk youth. During physical examination, reluctance to be weighed, vital sign abnormalities (eg, orthostatic hypotension, variability in pulse), skin abnormalities (lanugo hair, dryness), and marks indicating self-harm can serve as diagnostic indicators. Consider hospitalization for patients at <75% of their ideal body weight, who refuse to eat, or who show vital signs and laboratory abnormalities.

Media. By providing information on healthy eating and nutrition, the Internet can be an excellent resource for people with an eating disorder; however, you should also be aware of the impact of so-called pro-ana Web sites. People with anorexia use these Web sites to discuss their illness, but the sites sometimes glorify eating disorders as a lifestyle choice, and can be a place to share tips and tricks on extreme dieting, and might promote what is known as “thinspiration” in popular culture.

Meals. The American Dietetic Association recommends that anorexic patients begin oral intake at no more than 30 to 40 kcal/kg/day, and then gradually increase it, with a weight gain goal of 0.5 to 1 lb per week.

This graduated weight gain is done to prevent refeeding syndrome. After chronic starvation, intracellular phosphate stores are depleted and once carbohydrate intake resumes, insulin release causes phosphate to enter cells, thereby leading to hypophosphatemia. This electrolyte abnormality can result in cardiac failure. As a result, consider regular monitoring of phosphate levels, especially during the first week of reintroducing food.

Multimodal therapy. Despite being notoriously difficult to treat, patients with anorexia might respond to psychotherapy—especially family therapy—with an increased remission rate and faster return to health, compared with other forms of treatment. With a multimodal regimen involving proper refeeding techniques, family therapy, and medications as appropriate, recovery is possible.

Medications might be a helpful adjunct in patients who do not gain weight despite psychotherapy and proper nutritional measures. For example:

• There is some research on medications such as olanzapine and anxiolytics for treating anorexia.

• A low-dose anxiolytic might benefit patients with preprandial anxiety.

• Comorbid psychiatric disorders might improve during treatment of the eating disorder.

• Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and second-generation antipsychotics might help manage severe comorbid psychiatric disorders.

Because of low body weight and altered plasma protein binding, start medications at a low dosage. The risk of adverse effects can increase because more “free” medication is available. Consider avoiding medications such as bupropion and tricyclic antidepressants, because they carry an increased risk of seizures and cardiac effects, respectively.

Morbidity and mortality. Untreated anorexia has the highest mortality among psychiatric disorders: approximately 5.1 deaths for every 1,000 people.1 Recent meta-analyses show that patients with anorexia may have a 5.86 times greater risk of death than the general population.1 Serious sequelae include cardiac complications; osteoporosis; infertility; and comorbid psychiatric conditions such as substance abuse, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.2

Anorexia nervosa is associated with comorbid psychiatric disorders, severe physical complications, and high mortality. To help you remember important clinical information when working with patients with anorexia, we propose this “6 M” model for screening, treatment, and prognosis.

Monitor closely. Anorexia can go undiagnosed and untreated for years. During your patients’ office visits, ask about body image, exercise habits, and menstrual irregularities, especially when seeing at-risk youth. During physical examination, reluctance to be weighed, vital sign abnormalities (eg, orthostatic hypotension, variability in pulse), skin abnormalities (lanugo hair, dryness), and marks indicating self-harm can serve as diagnostic indicators. Consider hospitalization for patients at <75% of their ideal body weight, who refuse to eat, or who show vital signs and laboratory abnormalities.

Media. By providing information on healthy eating and nutrition, the Internet can be an excellent resource for people with an eating disorder; however, you should also be aware of the impact of so-called pro-ana Web sites. People with anorexia use these Web sites to discuss their illness, but the sites sometimes glorify eating disorders as a lifestyle choice, and can be a place to share tips and tricks on extreme dieting, and might promote what is known as “thinspiration” in popular culture.

Meals. The American Dietetic Association recommends that anorexic patients begin oral intake at no more than 30 to 40 kcal/kg/day, and then gradually increase it, with a weight gain goal of 0.5 to 1 lb per week.

This graduated weight gain is done to prevent refeeding syndrome. After chronic starvation, intracellular phosphate stores are depleted and once carbohydrate intake resumes, insulin release causes phosphate to enter cells, thereby leading to hypophosphatemia. This electrolyte abnormality can result in cardiac failure. As a result, consider regular monitoring of phosphate levels, especially during the first week of reintroducing food.

Multimodal therapy. Despite being notoriously difficult to treat, patients with anorexia might respond to psychotherapy—especially family therapy—with an increased remission rate and faster return to health, compared with other forms of treatment. With a multimodal regimen involving proper refeeding techniques, family therapy, and medications as appropriate, recovery is possible.

Medications might be a helpful adjunct in patients who do not gain weight despite psychotherapy and proper nutritional measures. For example:

• There is some research on medications such as olanzapine and anxiolytics for treating anorexia.

• A low-dose anxiolytic might benefit patients with preprandial anxiety.

• Comorbid psychiatric disorders might improve during treatment of the eating disorder.

• Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and second-generation antipsychotics might help manage severe comorbid psychiatric disorders.

Because of low body weight and altered plasma protein binding, start medications at a low dosage. The risk of adverse effects can increase because more “free” medication is available. Consider avoiding medications such as bupropion and tricyclic antidepressants, because they carry an increased risk of seizures and cardiac effects, respectively.

Morbidity and mortality. Untreated anorexia has the highest mortality among psychiatric disorders: approximately 5.1 deaths for every 1,000 people.1 Recent meta-analyses show that patients with anorexia may have a 5.86 times greater risk of death than the general population.1 Serious sequelae include cardiac complications; osteoporosis; infertility; and comorbid psychiatric conditions such as substance abuse, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.2

1. Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, et al. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011; 68(7):724-731.

2. Yager J, Andersen AE. Clinical practice. Anorexia nervosa. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(14):1481-1488.

1. Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, et al. Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011; 68(7):724-731.

2. Yager J, Andersen AE. Clinical practice. Anorexia nervosa. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(14):1481-1488.

First signs of a psychotic disorder

Schizophrenia prodrome: An optimal approach

In studies of schizophrenia, one of the more striking findings is the delay in the initiation of treatment. That delay ranges from 1 to 2 years for patients experiencing psychotic symptoms to several years if the prodromal phase is taken into account.1 Yet duration of untreated psychosis has been found to be a critical factor in prognosis, including psychosocial functioning, in patients with schizophrenia.2,3 Identification of individuals in the prodromal phase not only offers an opportunity to intervene at an earlier symptomatic stage, but might be associated with a better response to antipsychotics and a better overall treatment outcome as well.

What’s in a name?

Several terms, including ultra high risk, clinical high risk, at-risk mental state, psychosis risk syndrome, and schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome, have been used to describe the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. The proposal to include attenuated psychosis syndrome (APS) in the DSM-5—originally intended to capture those with subthreshold delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized behavior, occurring at least once a week for the past month and worsening over the past year—generated a debate about the validity of such a diagnostic category4,5 that culminated in the inclusion of APS as a condition for further study but not as a term for clinical use.6 Its presence in the DSM-5 brings to the forefront the importance of early clinical intervention in patients at risk of developing psychotic illness.

Schizophrenia is not inevitable

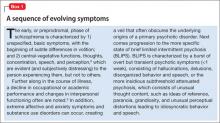

The prodromal phase can be viewed as a sequence of evolving symptoms7 (Box 18,9), starting with subtle differences evident only to the person experiencing them and often progressing to brief limited intermittent psychosis (BLIPS) or attenuated psychosis.8

In fact, prodrome is a retrospective diagnosis. The predictive power of conversion to psychosis has been found to fluctuate from as low as 9% to as high as 76%,10 prompting ethical concerns about a high false-positive rate, the assumption of inevitability associated with the term “schizophrenia prodrome,”9 and the potential for overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis. Concerns about psychosocial stigma and exposure to antipsychotic medications have been expressed as well.11

A case for early engagement

In retrospect, patients who eventually progress to psychotic illness are commonly found to have been in the prodromal phase for several years. Yet many patients’ first contact with psychiatric services occurs during a florid episode of acute psychosis. Identifying patients in the early prodromal period offers the opportunity to more effectively engage them and form a therapeutic alliance.12 Any young adult who presents with a decline in academic or occupational function, social withdrawal, perplexity, and apparent distress or agitation (Table 113-16) without a clear precipitating factor should therefore be closely monitored, particularly if he (she) has a family history of psychosis.

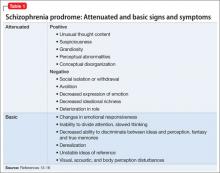

Screening tools. A variety of interviews and rating scales (Table 28) have been developed to assess and monitor at-risk persons, a number of which have been designed to detect basic symptoms in the early phase of prodrome. In addition to the structured scales, several self-report tools—including the Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief (PQ-B), Youth Psychosis At Risk Questionnaire-Brief (YPARQ-B), Prime Screen-Revised, and PROD-screen (Screen for prodromal symptoms of psychosis)—have been found to be useful in screening a large sample to identify those who might need further evaluation.17

Increased risk of conversion. Several clinical factors are associated with an increased risk of conversion to psychotic illness.9 In addition to family history, these include:

• greater severity and longer duration of attenuated positive symptoms

• presence of bizarre thoughts and behavior

• paranoia

• decline in global assessment of functioning score over the previous year

• use of either Cannabis or amphetamines.

A history of childhood trauma, increased sensitivity to psychosocial stressors, and dysregulation of the hypothalamicpituitary axis also have been associated with progression to psychosis.18

Recent evidence suggests that the prodromal phase is a predictor not only for psychosis but also for other disabling psychiatric illnesses, such as bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.19

From a phenomenological standpoint, disturbance of the sense of self—characterized by features such as depersonalization, derealization, decreased reactivity to other people and the environment, and intense reflectivity to oneself or others—has been proposed as a critical marker for progression to psychosis.20 Another predictor is the perception of negativity of others toward oneself. Examples include heightened sensitivity to rejection or shame, which seems to emerge from a pattern of insecure attachment, and the outsider status experienced by immigrants faced with multiple social, cultural, and language barriers.21 The presence of obsessivecompulsive symptoms during the prodromal phase has been linked to significant impairment in functioning, an acute switch to psychosis, and an increased risk of suicide.22

Monitor or treat? An optimal approach

A key dilemma in the management of patients who exhibit signs and symptoms of schizophrenia prodrome is whether to simply monitor closely or to initiate treatment.

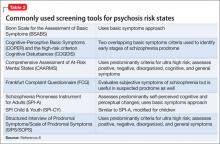

International clinical practice guidelines recommend several practical steps in the monitoring of patients in a prepsychotic state (Table 3),23 but caution against the use of antipsychotic agents unless the patient meets diagnostic criteria for a psychotic disorder.

CBT. Some evidence supports the initiation of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) during the initial prodromal phase and the addition of alow-dose atypical antipsychotic if the patient progresses to a later phase, characterized by BLIPS/APS.24,25 Evidence also suggests that a combination of CBT and antipsychotic medication might delay, but not prevent, the progression to a psychotic episode.9 Any risk of adverse metabolic complications precludes use ofan atypical antipsychotic.One potential alternative is the use of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (Box 2).26,27

A clinically useful approach would be to view schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome not as a distinct diagnostic category but as a cluster of signs and symptoms associated with an increased risk of psychosis, with persons in this phase in need of close follow-up and, possibly, early initiation of an antipsychotic agent. It is important to engage the patient and his family at an early stage to educate them about the diagnostic uncertainty; to help them deal with the stigma; to manage risk factors; and, collaboratively, to decide on an intervention strategy.23,28

Bottom Line

Despite several drawbacks, the concept of schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome may

be viewed as a cluster of signs and symptoms (rather than a distinct diagnostic category) associated with increased risk for psychosis that need close follow up. Follow up may involve psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic interventions and, need be, early initiation of antipsychotics. In addition, such symptoms may be associated with other psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder and obsessive- compulsive disorder. Timely attention and early intervention may alter the course

and improve overall prognosis.

Related Resources

• Early intervention in psychosis. WPA Education Committee’s recommended roles of the psychiatrist. www.wpanet.org/uploads/Education/Educational_Resources/earlyintervention-psychosis.pdf.

• Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre, Melbourne, Australia. http://eppic.org.au/psychosis.

• International Early Psychosis Association Writing Group. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:s120-124. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/187/48/s120.full.

Disclosures

Dr. Madaan is an employee of University of Virginia Health System. As an employee with the University of Virginia, Dr. Madaan has received research support from Eli Lilly and Company, Forest, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Shire, and Sunovion. He also has served as a consultant for the NOW Coalition for Bipolar Disorder, and on the American Psychiatric Association’s Focus Self-Assessment editorial board. Drs. Bestha and Kolli report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Salokangas RK, McGlashan TH. Early detection and intervention of psychosis. A review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008;62:92-105.

2. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10): 1785-1804.

3. Stefanopoulou E, Lafuente AR, Fonseca AS, et al. Global assessment of psychosocial functioning and predictors of outcome in schizophrenia. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2011;15(1):62-68.

4. Yung AR, Nelson B, Thompson AD, et al. Should a “Risk Syndrome for Psychosis” be included in the DSMV? Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):7-15.

5. Corcoran CM, First MB, Cornblatt B. The psychosis risk syndrome and its proposed inclusion in the DSM-V: a risk-benefit analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):16-22.

6. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

7. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Berning J, et al. Basic symptoms and ultrahigh risk criteria: symptom development in the initial prodromal state. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):182-191.

8. Correll CU, Hauser M, Auther AM, et al. Research in people with psychosis risk syndrome: a review of the current evidence and future directions. J Child Psychol

Psychiatry. 2010;51(4):390-431.

9. Addington J, Heinssen R. Prediction and prevention of psychosis in youth at clinical high risk. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:269-289.

10. Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(1):28-37.

11. Singh F, Mirzakhanian H, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Ethical implications for clinical practice and future research in “at risk” individuals. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):606-612.

12. Bota RG, Munro JS, Ricci WF, et al. The dynamics of insight in the prodrome of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(5):355-362.

13. Phillips LJ, Yung AR, McGorry PD. Identification of young people at risk of psychosis: validation of Personal Assessment and Crisis Evaluation Clinic intake criteria. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(suppl):S164-S169.

14. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Woods SW, et al. Symptom assessment in schizophrenic prodromal states. Psychiatr Q. 1999;70(4):273-287.

15. Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J, Picker H. Predicting first-episode psychosis by basic symptom criteria. Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2007;4(1):11-22.

16. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Picker H, et al. Basic symptoms in early psychotic and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;51:s31-s37.

17. Kline E, Wilson C, Ereshefsky S, et al. Convergent and discriminant validity of attenuated psychosis screening tools. Schizophr Res. 2012;134(1):49-53.

18. Holtzman CW, Shapiro DI, Trotman HD, et al. Stress and the prodromal phase of psychosis. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):527-533.

19. Rössler W, Hengartner MP, Ajdacic-Gross V, et al. Subclinical psychosis symptoms in young adults are risk factors for subsequent common mental disorders. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):18-23.

20. Nelson B, Yung AR, Bechdolf A, et al. The phenomenological critique and self-disturbance: implications for ultra-high risk (“prodrome”) research. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(2):381-392.

21. Salokangas RK, Heinimaa M, Svirskis T, et al. Perceived negative attitude of others as an early sign of psychosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(4):233-238.

22. Niendam TA, Berzak J, Cannon TD, et al. Obsessive compulsive symptoms in the psychosis prodrome:correlates of clinical and functional outcome. Schizophr

Res. 2009;108(1-3):170-175.

23. Addington J, Amminger GP, Barbato A. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:s120-s124.

24. Klosterkötter J, Schultze-Lutter F, Bechdolf A, et al. Prediction and prevention of schizophrenia: what has been achieved and where to go next? World Psychiatry.

2011;10(3):165-174.

25. Stafford MR, Jackson H, Mayo-Wilson E, et al. Early interventions to prevent psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f185.

In studies of schizophrenia, one of the more striking findings is the delay in the initiation of treatment. That delay ranges from 1 to 2 years for patients experiencing psychotic symptoms to several years if the prodromal phase is taken into account.1 Yet duration of untreated psychosis has been found to be a critical factor in prognosis, including psychosocial functioning, in patients with schizophrenia.2,3 Identification of individuals in the prodromal phase not only offers an opportunity to intervene at an earlier symptomatic stage, but might be associated with a better response to antipsychotics and a better overall treatment outcome as well.

What’s in a name?

Several terms, including ultra high risk, clinical high risk, at-risk mental state, psychosis risk syndrome, and schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome, have been used to describe the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. The proposal to include attenuated psychosis syndrome (APS) in the DSM-5—originally intended to capture those with subthreshold delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized behavior, occurring at least once a week for the past month and worsening over the past year—generated a debate about the validity of such a diagnostic category4,5 that culminated in the inclusion of APS as a condition for further study but not as a term for clinical use.6 Its presence in the DSM-5 brings to the forefront the importance of early clinical intervention in patients at risk of developing psychotic illness.

Schizophrenia is not inevitable

The prodromal phase can be viewed as a sequence of evolving symptoms7 (Box 18,9), starting with subtle differences evident only to the person experiencing them and often progressing to brief limited intermittent psychosis (BLIPS) or attenuated psychosis.8

In fact, prodrome is a retrospective diagnosis. The predictive power of conversion to psychosis has been found to fluctuate from as low as 9% to as high as 76%,10 prompting ethical concerns about a high false-positive rate, the assumption of inevitability associated with the term “schizophrenia prodrome,”9 and the potential for overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis. Concerns about psychosocial stigma and exposure to antipsychotic medications have been expressed as well.11

A case for early engagement

In retrospect, patients who eventually progress to psychotic illness are commonly found to have been in the prodromal phase for several years. Yet many patients’ first contact with psychiatric services occurs during a florid episode of acute psychosis. Identifying patients in the early prodromal period offers the opportunity to more effectively engage them and form a therapeutic alliance.12 Any young adult who presents with a decline in academic or occupational function, social withdrawal, perplexity, and apparent distress or agitation (Table 113-16) without a clear precipitating factor should therefore be closely monitored, particularly if he (she) has a family history of psychosis.

Screening tools. A variety of interviews and rating scales (Table 28) have been developed to assess and monitor at-risk persons, a number of which have been designed to detect basic symptoms in the early phase of prodrome. In addition to the structured scales, several self-report tools—including the Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief (PQ-B), Youth Psychosis At Risk Questionnaire-Brief (YPARQ-B), Prime Screen-Revised, and PROD-screen (Screen for prodromal symptoms of psychosis)—have been found to be useful in screening a large sample to identify those who might need further evaluation.17

Increased risk of conversion. Several clinical factors are associated with an increased risk of conversion to psychotic illness.9 In addition to family history, these include:

• greater severity and longer duration of attenuated positive symptoms

• presence of bizarre thoughts and behavior

• paranoia

• decline in global assessment of functioning score over the previous year

• use of either Cannabis or amphetamines.

A history of childhood trauma, increased sensitivity to psychosocial stressors, and dysregulation of the hypothalamicpituitary axis also have been associated with progression to psychosis.18

Recent evidence suggests that the prodromal phase is a predictor not only for psychosis but also for other disabling psychiatric illnesses, such as bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.19

From a phenomenological standpoint, disturbance of the sense of self—characterized by features such as depersonalization, derealization, decreased reactivity to other people and the environment, and intense reflectivity to oneself or others—has been proposed as a critical marker for progression to psychosis.20 Another predictor is the perception of negativity of others toward oneself. Examples include heightened sensitivity to rejection or shame, which seems to emerge from a pattern of insecure attachment, and the outsider status experienced by immigrants faced with multiple social, cultural, and language barriers.21 The presence of obsessivecompulsive symptoms during the prodromal phase has been linked to significant impairment in functioning, an acute switch to psychosis, and an increased risk of suicide.22

Monitor or treat? An optimal approach

A key dilemma in the management of patients who exhibit signs and symptoms of schizophrenia prodrome is whether to simply monitor closely or to initiate treatment.

International clinical practice guidelines recommend several practical steps in the monitoring of patients in a prepsychotic state (Table 3),23 but caution against the use of antipsychotic agents unless the patient meets diagnostic criteria for a psychotic disorder.

CBT. Some evidence supports the initiation of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) during the initial prodromal phase and the addition of alow-dose atypical antipsychotic if the patient progresses to a later phase, characterized by BLIPS/APS.24,25 Evidence also suggests that a combination of CBT and antipsychotic medication might delay, but not prevent, the progression to a psychotic episode.9 Any risk of adverse metabolic complications precludes use ofan atypical antipsychotic.One potential alternative is the use of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (Box 2).26,27

A clinically useful approach would be to view schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome not as a distinct diagnostic category but as a cluster of signs and symptoms associated with an increased risk of psychosis, with persons in this phase in need of close follow-up and, possibly, early initiation of an antipsychotic agent. It is important to engage the patient and his family at an early stage to educate them about the diagnostic uncertainty; to help them deal with the stigma; to manage risk factors; and, collaboratively, to decide on an intervention strategy.23,28

Bottom Line

Despite several drawbacks, the concept of schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome may

be viewed as a cluster of signs and symptoms (rather than a distinct diagnostic category) associated with increased risk for psychosis that need close follow up. Follow up may involve psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic interventions and, need be, early initiation of antipsychotics. In addition, such symptoms may be associated with other psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder and obsessive- compulsive disorder. Timely attention and early intervention may alter the course

and improve overall prognosis.

Related Resources

• Early intervention in psychosis. WPA Education Committee’s recommended roles of the psychiatrist. www.wpanet.org/uploads/Education/Educational_Resources/earlyintervention-psychosis.pdf.

• Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre, Melbourne, Australia. http://eppic.org.au/psychosis.

• International Early Psychosis Association Writing Group. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:s120-124. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/187/48/s120.full.

Disclosures

Dr. Madaan is an employee of University of Virginia Health System. As an employee with the University of Virginia, Dr. Madaan has received research support from Eli Lilly and Company, Forest, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Shire, and Sunovion. He also has served as a consultant for the NOW Coalition for Bipolar Disorder, and on the American Psychiatric Association’s Focus Self-Assessment editorial board. Drs. Bestha and Kolli report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

In studies of schizophrenia, one of the more striking findings is the delay in the initiation of treatment. That delay ranges from 1 to 2 years for patients experiencing psychotic symptoms to several years if the prodromal phase is taken into account.1 Yet duration of untreated psychosis has been found to be a critical factor in prognosis, including psychosocial functioning, in patients with schizophrenia.2,3 Identification of individuals in the prodromal phase not only offers an opportunity to intervene at an earlier symptomatic stage, but might be associated with a better response to antipsychotics and a better overall treatment outcome as well.

What’s in a name?

Several terms, including ultra high risk, clinical high risk, at-risk mental state, psychosis risk syndrome, and schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome, have been used to describe the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. The proposal to include attenuated psychosis syndrome (APS) in the DSM-5—originally intended to capture those with subthreshold delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized behavior, occurring at least once a week for the past month and worsening over the past year—generated a debate about the validity of such a diagnostic category4,5 that culminated in the inclusion of APS as a condition for further study but not as a term for clinical use.6 Its presence in the DSM-5 brings to the forefront the importance of early clinical intervention in patients at risk of developing psychotic illness.

Schizophrenia is not inevitable

The prodromal phase can be viewed as a sequence of evolving symptoms7 (Box 18,9), starting with subtle differences evident only to the person experiencing them and often progressing to brief limited intermittent psychosis (BLIPS) or attenuated psychosis.8

In fact, prodrome is a retrospective diagnosis. The predictive power of conversion to psychosis has been found to fluctuate from as low as 9% to as high as 76%,10 prompting ethical concerns about a high false-positive rate, the assumption of inevitability associated with the term “schizophrenia prodrome,”9 and the potential for overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis. Concerns about psychosocial stigma and exposure to antipsychotic medications have been expressed as well.11

A case for early engagement

In retrospect, patients who eventually progress to psychotic illness are commonly found to have been in the prodromal phase for several years. Yet many patients’ first contact with psychiatric services occurs during a florid episode of acute psychosis. Identifying patients in the early prodromal period offers the opportunity to more effectively engage them and form a therapeutic alliance.12 Any young adult who presents with a decline in academic or occupational function, social withdrawal, perplexity, and apparent distress or agitation (Table 113-16) without a clear precipitating factor should therefore be closely monitored, particularly if he (she) has a family history of psychosis.

Screening tools. A variety of interviews and rating scales (Table 28) have been developed to assess and monitor at-risk persons, a number of which have been designed to detect basic symptoms in the early phase of prodrome. In addition to the structured scales, several self-report tools—including the Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief (PQ-B), Youth Psychosis At Risk Questionnaire-Brief (YPARQ-B), Prime Screen-Revised, and PROD-screen (Screen for prodromal symptoms of psychosis)—have been found to be useful in screening a large sample to identify those who might need further evaluation.17

Increased risk of conversion. Several clinical factors are associated with an increased risk of conversion to psychotic illness.9 In addition to family history, these include:

• greater severity and longer duration of attenuated positive symptoms

• presence of bizarre thoughts and behavior

• paranoia

• decline in global assessment of functioning score over the previous year

• use of either Cannabis or amphetamines.

A history of childhood trauma, increased sensitivity to psychosocial stressors, and dysregulation of the hypothalamicpituitary axis also have been associated with progression to psychosis.18

Recent evidence suggests that the prodromal phase is a predictor not only for psychosis but also for other disabling psychiatric illnesses, such as bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.19

From a phenomenological standpoint, disturbance of the sense of self—characterized by features such as depersonalization, derealization, decreased reactivity to other people and the environment, and intense reflectivity to oneself or others—has been proposed as a critical marker for progression to psychosis.20 Another predictor is the perception of negativity of others toward oneself. Examples include heightened sensitivity to rejection or shame, which seems to emerge from a pattern of insecure attachment, and the outsider status experienced by immigrants faced with multiple social, cultural, and language barriers.21 The presence of obsessivecompulsive symptoms during the prodromal phase has been linked to significant impairment in functioning, an acute switch to psychosis, and an increased risk of suicide.22

Monitor or treat? An optimal approach

A key dilemma in the management of patients who exhibit signs and symptoms of schizophrenia prodrome is whether to simply monitor closely or to initiate treatment.

International clinical practice guidelines recommend several practical steps in the monitoring of patients in a prepsychotic state (Table 3),23 but caution against the use of antipsychotic agents unless the patient meets diagnostic criteria for a psychotic disorder.

CBT. Some evidence supports the initiation of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) during the initial prodromal phase and the addition of alow-dose atypical antipsychotic if the patient progresses to a later phase, characterized by BLIPS/APS.24,25 Evidence also suggests that a combination of CBT and antipsychotic medication might delay, but not prevent, the progression to a psychotic episode.9 Any risk of adverse metabolic complications precludes use ofan atypical antipsychotic.One potential alternative is the use of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (Box 2).26,27

A clinically useful approach would be to view schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome not as a distinct diagnostic category but as a cluster of signs and symptoms associated with an increased risk of psychosis, with persons in this phase in need of close follow-up and, possibly, early initiation of an antipsychotic agent. It is important to engage the patient and his family at an early stage to educate them about the diagnostic uncertainty; to help them deal with the stigma; to manage risk factors; and, collaboratively, to decide on an intervention strategy.23,28

Bottom Line

Despite several drawbacks, the concept of schizophrenia/psychosis prodrome may

be viewed as a cluster of signs and symptoms (rather than a distinct diagnostic category) associated with increased risk for psychosis that need close follow up. Follow up may involve psychoeducational and psychotherapeutic interventions and, need be, early initiation of antipsychotics. In addition, such symptoms may be associated with other psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder and obsessive- compulsive disorder. Timely attention and early intervention may alter the course

and improve overall prognosis.

Related Resources

• Early intervention in psychosis. WPA Education Committee’s recommended roles of the psychiatrist. www.wpanet.org/uploads/Education/Educational_Resources/earlyintervention-psychosis.pdf.

• Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre, Melbourne, Australia. http://eppic.org.au/psychosis.

• International Early Psychosis Association Writing Group. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:s120-124. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/187/48/s120.full.

Disclosures

Dr. Madaan is an employee of University of Virginia Health System. As an employee with the University of Virginia, Dr. Madaan has received research support from Eli Lilly and Company, Forest, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Shire, and Sunovion. He also has served as a consultant for the NOW Coalition for Bipolar Disorder, and on the American Psychiatric Association’s Focus Self-Assessment editorial board. Drs. Bestha and Kolli report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Salokangas RK, McGlashan TH. Early detection and intervention of psychosis. A review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008;62:92-105.

2. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10): 1785-1804.

3. Stefanopoulou E, Lafuente AR, Fonseca AS, et al. Global assessment of psychosocial functioning and predictors of outcome in schizophrenia. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2011;15(1):62-68.

4. Yung AR, Nelson B, Thompson AD, et al. Should a “Risk Syndrome for Psychosis” be included in the DSMV? Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):7-15.

5. Corcoran CM, First MB, Cornblatt B. The psychosis risk syndrome and its proposed inclusion in the DSM-V: a risk-benefit analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):16-22.

6. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

7. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Berning J, et al. Basic symptoms and ultrahigh risk criteria: symptom development in the initial prodromal state. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):182-191.

8. Correll CU, Hauser M, Auther AM, et al. Research in people with psychosis risk syndrome: a review of the current evidence and future directions. J Child Psychol

Psychiatry. 2010;51(4):390-431.

9. Addington J, Heinssen R. Prediction and prevention of psychosis in youth at clinical high risk. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:269-289.

10. Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(1):28-37.

11. Singh F, Mirzakhanian H, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Ethical implications for clinical practice and future research in “at risk” individuals. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):606-612.

12. Bota RG, Munro JS, Ricci WF, et al. The dynamics of insight in the prodrome of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(5):355-362.

13. Phillips LJ, Yung AR, McGorry PD. Identification of young people at risk of psychosis: validation of Personal Assessment and Crisis Evaluation Clinic intake criteria. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(suppl):S164-S169.

14. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Woods SW, et al. Symptom assessment in schizophrenic prodromal states. Psychiatr Q. 1999;70(4):273-287.

15. Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J, Picker H. Predicting first-episode psychosis by basic symptom criteria. Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2007;4(1):11-22.

16. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Picker H, et al. Basic symptoms in early psychotic and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;51:s31-s37.

17. Kline E, Wilson C, Ereshefsky S, et al. Convergent and discriminant validity of attenuated psychosis screening tools. Schizophr Res. 2012;134(1):49-53.

18. Holtzman CW, Shapiro DI, Trotman HD, et al. Stress and the prodromal phase of psychosis. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):527-533.

19. Rössler W, Hengartner MP, Ajdacic-Gross V, et al. Subclinical psychosis symptoms in young adults are risk factors for subsequent common mental disorders. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):18-23.

20. Nelson B, Yung AR, Bechdolf A, et al. The phenomenological critique and self-disturbance: implications for ultra-high risk (“prodrome”) research. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(2):381-392.

21. Salokangas RK, Heinimaa M, Svirskis T, et al. Perceived negative attitude of others as an early sign of psychosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(4):233-238.

22. Niendam TA, Berzak J, Cannon TD, et al. Obsessive compulsive symptoms in the psychosis prodrome:correlates of clinical and functional outcome. Schizophr

Res. 2009;108(1-3):170-175.

23. Addington J, Amminger GP, Barbato A. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:s120-s124.

24. Klosterkötter J, Schultze-Lutter F, Bechdolf A, et al. Prediction and prevention of schizophrenia: what has been achieved and where to go next? World Psychiatry.

2011;10(3):165-174.

25. Stafford MR, Jackson H, Mayo-Wilson E, et al. Early interventions to prevent psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f185.

1. Salokangas RK, McGlashan TH. Early detection and intervention of psychosis. A review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008;62:92-105.

2. Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, et al. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10): 1785-1804.

3. Stefanopoulou E, Lafuente AR, Fonseca AS, et al. Global assessment of psychosocial functioning and predictors of outcome in schizophrenia. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2011;15(1):62-68.

4. Yung AR, Nelson B, Thompson AD, et al. Should a “Risk Syndrome for Psychosis” be included in the DSMV? Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):7-15.

5. Corcoran CM, First MB, Cornblatt B. The psychosis risk syndrome and its proposed inclusion in the DSM-V: a risk-benefit analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1-3):16-22.

6. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

7. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Berning J, et al. Basic symptoms and ultrahigh risk criteria: symptom development in the initial prodromal state. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(1):182-191.

8. Correll CU, Hauser M, Auther AM, et al. Research in people with psychosis risk syndrome: a review of the current evidence and future directions. J Child Psychol

Psychiatry. 2010;51(4):390-431.

9. Addington J, Heinssen R. Prediction and prevention of psychosis in youth at clinical high risk. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:269-289.

10. Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(1):28-37.

11. Singh F, Mirzakhanian H, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Ethical implications for clinical practice and future research in “at risk” individuals. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):606-612.

12. Bota RG, Munro JS, Ricci WF, et al. The dynamics of insight in the prodrome of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(5):355-362.

13. Phillips LJ, Yung AR, McGorry PD. Identification of young people at risk of psychosis: validation of Personal Assessment and Crisis Evaluation Clinic intake criteria. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(suppl):S164-S169.

14. Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Woods SW, et al. Symptom assessment in schizophrenic prodromal states. Psychiatr Q. 1999;70(4):273-287.

15. Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkötter J, Picker H. Predicting first-episode psychosis by basic symptom criteria. Clinical Neuropsychiatry. 2007;4(1):11-22.

16. Schultze-Lutter F, Ruhrmann S, Picker H, et al. Basic symptoms in early psychotic and depressive disorders. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2007;51:s31-s37.

17. Kline E, Wilson C, Ereshefsky S, et al. Convergent and discriminant validity of attenuated psychosis screening tools. Schizophr Res. 2012;134(1):49-53.

18. Holtzman CW, Shapiro DI, Trotman HD, et al. Stress and the prodromal phase of psychosis. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(4):527-533.

19. Rössler W, Hengartner MP, Ajdacic-Gross V, et al. Subclinical psychosis symptoms in young adults are risk factors for subsequent common mental disorders. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1-3):18-23.

20. Nelson B, Yung AR, Bechdolf A, et al. The phenomenological critique and self-disturbance: implications for ultra-high risk (“prodrome”) research. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(2):381-392.

21. Salokangas RK, Heinimaa M, Svirskis T, et al. Perceived negative attitude of others as an early sign of psychosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24(4):233-238.

22. Niendam TA, Berzak J, Cannon TD, et al. Obsessive compulsive symptoms in the psychosis prodrome:correlates of clinical and functional outcome. Schizophr

Res. 2009;108(1-3):170-175.

23. Addington J, Amminger GP, Barbato A. International clinical practice guidelines for early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:s120-s124.

24. Klosterkötter J, Schultze-Lutter F, Bechdolf A, et al. Prediction and prevention of schizophrenia: what has been achieved and where to go next? World Psychiatry.

2011;10(3):165-174.

25. Stafford MR, Jackson H, Mayo-Wilson E, et al. Early interventions to prevent psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f185.

Psychiatric assessment: A word to the WISE

Most clinicians can easily identify the biological and psychological aspects of mental illness, but the social components often are overlooked.1 These include a negative life event, familial or interpersonal stressor, environmental difficulty or deficiency, or inadequate social support.2

We have found that these significant psychosocial factors listed in DSM-IV-TR2 can be easily assessed using the mnemonic, “Family and friends with a WISE HALO.”

Family and friends. Stressful events include family disruption by divorce or separation; illness or death of family members; neglect; emotional, physical or sexual abuse; remarriage of a parent; or birth or adoption of a new sibling.

Work. Stressors associated with work include actual or perceived job loss, difficult working conditions, irregular schedules, difficulty getting along with superiors or coworkers, and job dissatisfaction.

Income. Poverty and inadequate finances can influence the patient’s mental health.

Social environment. Problems with living alone, poor support, difficulty with acculturation, and discrimination are some possible difficulties.

Education. Learning problems, conflicts with teachers and classmates, bullying, and illiteracy could harm your patient’s mental health.

Housing. Stressors include homelessness, unsafe neighborhoods, and problems with a landlord.

Access to health care services. Inadequate access to health care, lack of medical insurance, and absence of transportation can influence your patient’s care.

Legal. Arrest, incarceration, ongoing lawsuits, and being the perpetrator or victim of a crime are included here.

Others. This catchall category includes exposure to disasters or wars and unavailability of social services.

After identifying the psychosocial issues affecting your patient, assimilate this information into a biopsychosocial formulation and treatment plan. Interventions could include referrals for individual and family therapy, bereavement and support groups, recreational therapy, or to subsidized housing programs or job training.

1. Campbell WH, Rohrbaugh RM. The biopsychosocial formulation manual. A guide for mental health professionals. New York: Routledge; 2006:63-70.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Dr. Madaan is a fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry at Creighton University, Omaha, NE.

Dr. Kohli is a practicing family physician in Amherst, VA.

Dr. Khurana is a clinical observer and visiting researcher at Children’s Hospital, Omaha, NE.

Most clinicians can easily identify the biological and psychological aspects of mental illness, but the social components often are overlooked.1 These include a negative life event, familial or interpersonal stressor, environmental difficulty or deficiency, or inadequate social support.2

We have found that these significant psychosocial factors listed in DSM-IV-TR2 can be easily assessed using the mnemonic, “Family and friends with a WISE HALO.”

Family and friends. Stressful events include family disruption by divorce or separation; illness or death of family members; neglect; emotional, physical or sexual abuse; remarriage of a parent; or birth or adoption of a new sibling.

Work. Stressors associated with work include actual or perceived job loss, difficult working conditions, irregular schedules, difficulty getting along with superiors or coworkers, and job dissatisfaction.

Income. Poverty and inadequate finances can influence the patient’s mental health.

Social environment. Problems with living alone, poor support, difficulty with acculturation, and discrimination are some possible difficulties.

Education. Learning problems, conflicts with teachers and classmates, bullying, and illiteracy could harm your patient’s mental health.

Housing. Stressors include homelessness, unsafe neighborhoods, and problems with a landlord.

Access to health care services. Inadequate access to health care, lack of medical insurance, and absence of transportation can influence your patient’s care.

Legal. Arrest, incarceration, ongoing lawsuits, and being the perpetrator or victim of a crime are included here.

Others. This catchall category includes exposure to disasters or wars and unavailability of social services.

After identifying the psychosocial issues affecting your patient, assimilate this information into a biopsychosocial formulation and treatment plan. Interventions could include referrals for individual and family therapy, bereavement and support groups, recreational therapy, or to subsidized housing programs or job training.

Most clinicians can easily identify the biological and psychological aspects of mental illness, but the social components often are overlooked.1 These include a negative life event, familial or interpersonal stressor, environmental difficulty or deficiency, or inadequate social support.2

We have found that these significant psychosocial factors listed in DSM-IV-TR2 can be easily assessed using the mnemonic, “Family and friends with a WISE HALO.”

Family and friends. Stressful events include family disruption by divorce or separation; illness or death of family members; neglect; emotional, physical or sexual abuse; remarriage of a parent; or birth or adoption of a new sibling.

Work. Stressors associated with work include actual or perceived job loss, difficult working conditions, irregular schedules, difficulty getting along with superiors or coworkers, and job dissatisfaction.

Income. Poverty and inadequate finances can influence the patient’s mental health.

Social environment. Problems with living alone, poor support, difficulty with acculturation, and discrimination are some possible difficulties.

Education. Learning problems, conflicts with teachers and classmates, bullying, and illiteracy could harm your patient’s mental health.

Housing. Stressors include homelessness, unsafe neighborhoods, and problems with a landlord.

Access to health care services. Inadequate access to health care, lack of medical insurance, and absence of transportation can influence your patient’s care.

Legal. Arrest, incarceration, ongoing lawsuits, and being the perpetrator or victim of a crime are included here.

Others. This catchall category includes exposure to disasters or wars and unavailability of social services.

After identifying the psychosocial issues affecting your patient, assimilate this information into a biopsychosocial formulation and treatment plan. Interventions could include referrals for individual and family therapy, bereavement and support groups, recreational therapy, or to subsidized housing programs or job training.

1. Campbell WH, Rohrbaugh RM. The biopsychosocial formulation manual. A guide for mental health professionals. New York: Routledge; 2006:63-70.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Dr. Madaan is a fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry at Creighton University, Omaha, NE.

Dr. Kohli is a practicing family physician in Amherst, VA.

Dr. Khurana is a clinical observer and visiting researcher at Children’s Hospital, Omaha, NE.

1. Campbell WH, Rohrbaugh RM. The biopsychosocial formulation manual. A guide for mental health professionals. New York: Routledge; 2006:63-70.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Dr. Madaan is a fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry at Creighton University, Omaha, NE.

Dr. Kohli is a practicing family physician in Amherst, VA.

Dr. Khurana is a clinical observer and visiting researcher at Children’s Hospital, Omaha, NE.

How to diagnose pathologic gambling in older patients

Pathologic gambling among older patients causes more than financial losses; it also can lead to comorbid alcohol dependence, depression, anxiety disorders, and medical treatment nonadherence.1

Retirement, death of a spouse, “empty nest” syndrome, and other emotional, social, and financial stresses are common in later life. Some try to fill the gap with gambling, which can become pathologic. Early intervention and treatments addressing an older patient’s psychological and social needs can improve outcomes, however.

Screening for pathologic gambling

Late life pathologic gambling often goes undiagnosed but is thought to be on the rise. In a random sample of 843 older adults at scheduled primary-care appointments, 70% had gambled at least once in the past year and 11% were identified as at-risk gamblers.1

Diagnosing pathologic gambling requires a high degree of suspicion and inquiry. You must actively incorporate screening questions in the clinical interview to identify at-risk and pathologic gamblers in older patients.

Based on clinical experience and several DSM-IV-TR criteria,2 we developed a screening tool called PACE RULeS to identify pathologic gambling in this population (Box 1). A positive response to 5 or more of the 8 questions indicates a likely diagnosis of pathologic gambling. Lower scores may point to at-risk behavior and would require follow-up.

Diagnose maladaptive or pathologic gambling if your patient answers yes to 5 or more of these “PACE RULeS” questions:

- P—Are you often Preoccupied with thoughts of gambling?

- A—Would you often gamble with increasing Amounts of money to achieve the same excitement?

- C—Have you made repeated efforts to Control, cut back, or stop gambling?

- E—Do you gamble to Escape daily problems and stresses?

- R—After losing money, do you often Return another day to get even?

- U—Have you ever committed Unlawful acts to finance gambling?

- L—Have you Lost a significant relationship or job because of gambling?

- S—Do you use your Savings to gamble?

Psychosocial intervention

After you make a diagnosis, manage your patient’s pathologic gambling with a comprehensive plan that includes family and community resources.3 Box 2 shows interventions studied in the adult population that are appropriate for older patients.

- Screen for active gambling

- Intervene immediately if the patient is suicidal

- Refer the patient to Gamblers Anonymous

- Enlist family and friends to support treatment adherence and effectiveness. Be aware of confidentiality and ethical issues, however, especially during discussions with family members

- Refer the patient to counseling

- Actively participate in the treatment plan by assessing for relapses.

Medication

No psychotropics are FDA-approved for pathologic gambling, but adding medication to psychosocial interventions may help. Most medications studied in the general population are similarly efficacious in older adults. Slowly increase dosages, however, because of the greater risk of side effects in older patients.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors help reduce gambling behavior, improve social and occupational functioning, and treat comorbid depression when used in relatively higher dosages. In anecdotal reports, the following medications have been found to be beneficial:

Although some medications treat pathologic gambling, others can cause it. Dopamine agonists such as pramipexole could cause reversible pathologic gambling in some older individuals who take it for Parkinson’s disease or restless legs syndrome.10

Drug brand names

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

- Naltrexone • ReVia

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Pramipexole • Mirapex

- Valproate • Depakene, Depakote

1. Levens S, Dyer AM, Zubritsky C, et al. Gambling among older, primary-care patients: an important public health concern. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;13(1):69-76.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Unwin B, Davis M, DeLeeuw J. Pathological gambling. Am Fam Physician 2000;61:741-9.

4. De la Gandara JJ. Fluoxetine: open-trial in pathological gambling. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 16-21, 1999; Washington, DC.

5. Kim SW, Grant JE, Adson DE, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of paroxetine in the treatment of pathological gambling. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(6):501-7.

6. Hollander E, DeCaria CM, Mari E, et al. Short-term single-blind fluvoxamine treatment of pathological gambling. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155(12):1781-3.

7. Hollander E, DeCaria CM, Finkell JN, et al. A randomized double-blind fluvoxamine/placebo crossover trial in pathological gambling. Biol Psychiatry 2000;47(9):813-7.

8. Zimmerman M, Breen RB, Posternak MA. An open-label study of citalopram in the treatment of pathological gambling. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(1):44-8.

9. Kim SW, Grant JE. An open naltrexone treatment study of pathological gambling disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;16(5):285-9.

10. Dodd ML, Klos KJ, Bower JH, et al. Pathological gambling caused by drugs used to treat Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 2005;62(9):1377-81.

Dr. Madaan is a fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry, Creighton University, Omaha, NE.

Dr. Padala is assistant professor, department of psychiatry, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE.

Dr. Sattar is assistant professor, department of psychiatry, Creighton University Medical Center, Omaha, NE.

Pathologic gambling among older patients causes more than financial losses; it also can lead to comorbid alcohol dependence, depression, anxiety disorders, and medical treatment nonadherence.1

Retirement, death of a spouse, “empty nest” syndrome, and other emotional, social, and financial stresses are common in later life. Some try to fill the gap with gambling, which can become pathologic. Early intervention and treatments addressing an older patient’s psychological and social needs can improve outcomes, however.

Screening for pathologic gambling

Late life pathologic gambling often goes undiagnosed but is thought to be on the rise. In a random sample of 843 older adults at scheduled primary-care appointments, 70% had gambled at least once in the past year and 11% were identified as at-risk gamblers.1

Diagnosing pathologic gambling requires a high degree of suspicion and inquiry. You must actively incorporate screening questions in the clinical interview to identify at-risk and pathologic gamblers in older patients.

Based on clinical experience and several DSM-IV-TR criteria,2 we developed a screening tool called PACE RULeS to identify pathologic gambling in this population (Box 1). A positive response to 5 or more of the 8 questions indicates a likely diagnosis of pathologic gambling. Lower scores may point to at-risk behavior and would require follow-up.

Diagnose maladaptive or pathologic gambling if your patient answers yes to 5 or more of these “PACE RULeS” questions:

- P—Are you often Preoccupied with thoughts of gambling?

- A—Would you often gamble with increasing Amounts of money to achieve the same excitement?

- C—Have you made repeated efforts to Control, cut back, or stop gambling?

- E—Do you gamble to Escape daily problems and stresses?

- R—After losing money, do you often Return another day to get even?

- U—Have you ever committed Unlawful acts to finance gambling?

- L—Have you Lost a significant relationship or job because of gambling?

- S—Do you use your Savings to gamble?

Psychosocial intervention

After you make a diagnosis, manage your patient’s pathologic gambling with a comprehensive plan that includes family and community resources.3 Box 2 shows interventions studied in the adult population that are appropriate for older patients.

- Screen for active gambling

- Intervene immediately if the patient is suicidal

- Refer the patient to Gamblers Anonymous

- Enlist family and friends to support treatment adherence and effectiveness. Be aware of confidentiality and ethical issues, however, especially during discussions with family members

- Refer the patient to counseling

- Actively participate in the treatment plan by assessing for relapses.

Medication

No psychotropics are FDA-approved for pathologic gambling, but adding medication to psychosocial interventions may help. Most medications studied in the general population are similarly efficacious in older adults. Slowly increase dosages, however, because of the greater risk of side effects in older patients.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors help reduce gambling behavior, improve social and occupational functioning, and treat comorbid depression when used in relatively higher dosages. In anecdotal reports, the following medications have been found to be beneficial:

Although some medications treat pathologic gambling, others can cause it. Dopamine agonists such as pramipexole could cause reversible pathologic gambling in some older individuals who take it for Parkinson’s disease or restless legs syndrome.10

Drug brand names

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

- Naltrexone • ReVia

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Pramipexole • Mirapex

- Valproate • Depakene, Depakote

Pathologic gambling among older patients causes more than financial losses; it also can lead to comorbid alcohol dependence, depression, anxiety disorders, and medical treatment nonadherence.1

Retirement, death of a spouse, “empty nest” syndrome, and other emotional, social, and financial stresses are common in later life. Some try to fill the gap with gambling, which can become pathologic. Early intervention and treatments addressing an older patient’s psychological and social needs can improve outcomes, however.

Screening for pathologic gambling

Late life pathologic gambling often goes undiagnosed but is thought to be on the rise. In a random sample of 843 older adults at scheduled primary-care appointments, 70% had gambled at least once in the past year and 11% were identified as at-risk gamblers.1

Diagnosing pathologic gambling requires a high degree of suspicion and inquiry. You must actively incorporate screening questions in the clinical interview to identify at-risk and pathologic gamblers in older patients.

Based on clinical experience and several DSM-IV-TR criteria,2 we developed a screening tool called PACE RULeS to identify pathologic gambling in this population (Box 1). A positive response to 5 or more of the 8 questions indicates a likely diagnosis of pathologic gambling. Lower scores may point to at-risk behavior and would require follow-up.

Diagnose maladaptive or pathologic gambling if your patient answers yes to 5 or more of these “PACE RULeS” questions:

- P—Are you often Preoccupied with thoughts of gambling?

- A—Would you often gamble with increasing Amounts of money to achieve the same excitement?

- C—Have you made repeated efforts to Control, cut back, or stop gambling?

- E—Do you gamble to Escape daily problems and stresses?

- R—After losing money, do you often Return another day to get even?

- U—Have you ever committed Unlawful acts to finance gambling?

- L—Have you Lost a significant relationship or job because of gambling?

- S—Do you use your Savings to gamble?

Psychosocial intervention

After you make a diagnosis, manage your patient’s pathologic gambling with a comprehensive plan that includes family and community resources.3 Box 2 shows interventions studied in the adult population that are appropriate for older patients.

- Screen for active gambling

- Intervene immediately if the patient is suicidal

- Refer the patient to Gamblers Anonymous

- Enlist family and friends to support treatment adherence and effectiveness. Be aware of confidentiality and ethical issues, however, especially during discussions with family members

- Refer the patient to counseling

- Actively participate in the treatment plan by assessing for relapses.

Medication

No psychotropics are FDA-approved for pathologic gambling, but adding medication to psychosocial interventions may help. Most medications studied in the general population are similarly efficacious in older adults. Slowly increase dosages, however, because of the greater risk of side effects in older patients.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors help reduce gambling behavior, improve social and occupational functioning, and treat comorbid depression when used in relatively higher dosages. In anecdotal reports, the following medications have been found to be beneficial:

Although some medications treat pathologic gambling, others can cause it. Dopamine agonists such as pramipexole could cause reversible pathologic gambling in some older individuals who take it for Parkinson’s disease or restless legs syndrome.10

Drug brand names

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clomipramine • Anafranil

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Fluvoxamine • Luvox

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

- Naltrexone • ReVia

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Pramipexole • Mirapex

- Valproate • Depakene, Depakote

1. Levens S, Dyer AM, Zubritsky C, et al. Gambling among older, primary-care patients: an important public health concern. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;13(1):69-76.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Unwin B, Davis M, DeLeeuw J. Pathological gambling. Am Fam Physician 2000;61:741-9.

4. De la Gandara JJ. Fluoxetine: open-trial in pathological gambling. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 16-21, 1999; Washington, DC.

5. Kim SW, Grant JE, Adson DE, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of paroxetine in the treatment of pathological gambling. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(6):501-7.

6. Hollander E, DeCaria CM, Mari E, et al. Short-term single-blind fluvoxamine treatment of pathological gambling. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155(12):1781-3.

7. Hollander E, DeCaria CM, Finkell JN, et al. A randomized double-blind fluvoxamine/placebo crossover trial in pathological gambling. Biol Psychiatry 2000;47(9):813-7.

8. Zimmerman M, Breen RB, Posternak MA. An open-label study of citalopram in the treatment of pathological gambling. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(1):44-8.

9. Kim SW, Grant JE. An open naltrexone treatment study of pathological gambling disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;16(5):285-9.

10. Dodd ML, Klos KJ, Bower JH, et al. Pathological gambling caused by drugs used to treat Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 2005;62(9):1377-81.

Dr. Madaan is a fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry, Creighton University, Omaha, NE.

Dr. Padala is assistant professor, department of psychiatry, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE.

Dr. Sattar is assistant professor, department of psychiatry, Creighton University Medical Center, Omaha, NE.

1. Levens S, Dyer AM, Zubritsky C, et al. Gambling among older, primary-care patients: an important public health concern. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;13(1):69-76.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

3. Unwin B, Davis M, DeLeeuw J. Pathological gambling. Am Fam Physician 2000;61:741-9.

4. De la Gandara JJ. Fluoxetine: open-trial in pathological gambling. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 16-21, 1999; Washington, DC.

5. Kim SW, Grant JE, Adson DE, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of paroxetine in the treatment of pathological gambling. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(6):501-7.

6. Hollander E, DeCaria CM, Mari E, et al. Short-term single-blind fluvoxamine treatment of pathological gambling. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155(12):1781-3.

7. Hollander E, DeCaria CM, Finkell JN, et al. A randomized double-blind fluvoxamine/placebo crossover trial in pathological gambling. Biol Psychiatry 2000;47(9):813-7.

8. Zimmerman M, Breen RB, Posternak MA. An open-label study of citalopram in the treatment of pathological gambling. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(1):44-8.

9. Kim SW, Grant JE. An open naltrexone treatment study of pathological gambling disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;16(5):285-9.

10. Dodd ML, Klos KJ, Bower JH, et al. Pathological gambling caused by drugs used to treat Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 2005;62(9):1377-81.

Dr. Madaan is a fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry, Creighton University, Omaha, NE.

Dr. Padala is assistant professor, department of psychiatry, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE.

Dr. Sattar is assistant professor, department of psychiatry, Creighton University Medical Center, Omaha, NE.