User login

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a significant public health problem worldwide with an estimated 10.4 million new cases and 1.7 million deaths having occurred in 2016.1 In that same year, there were 9287 new cases in the United States—the lowest number of TB cases on record.2

TB appears in one of 2 forms: active disease, which causes symptoms, morbidity, and mortality and is a source of transmission to others; and latent TB infection (LTBI), which is asymptomatic and noninfectious but can progress to active disease. The estimated prevalence of LTBI worldwide is 23%,3 although in the United States it is only about 5%.4 The proportion of those with LTBI who will develop active disease is estimated at 5% to 10% and is highly variable depending on risks.4

In the United States, about two-thirds of active TB cases occur among those who are foreign born, whose rate of active disease is 14.6/100,000.2 Five countries account for more than half of foreign-born cases: Mexico, the Philippines, India, Vietnam, and China.2

Who should be tested?

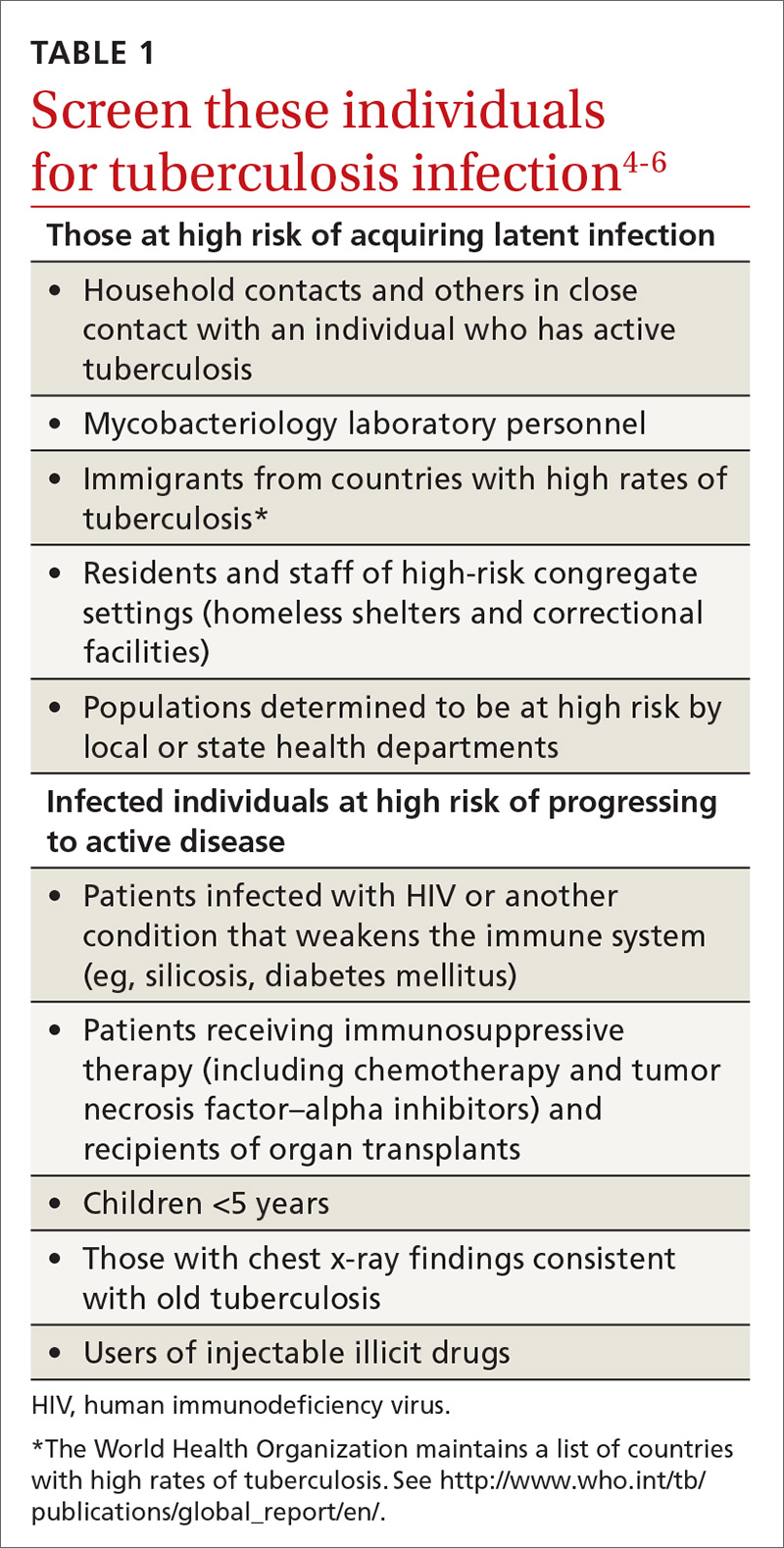

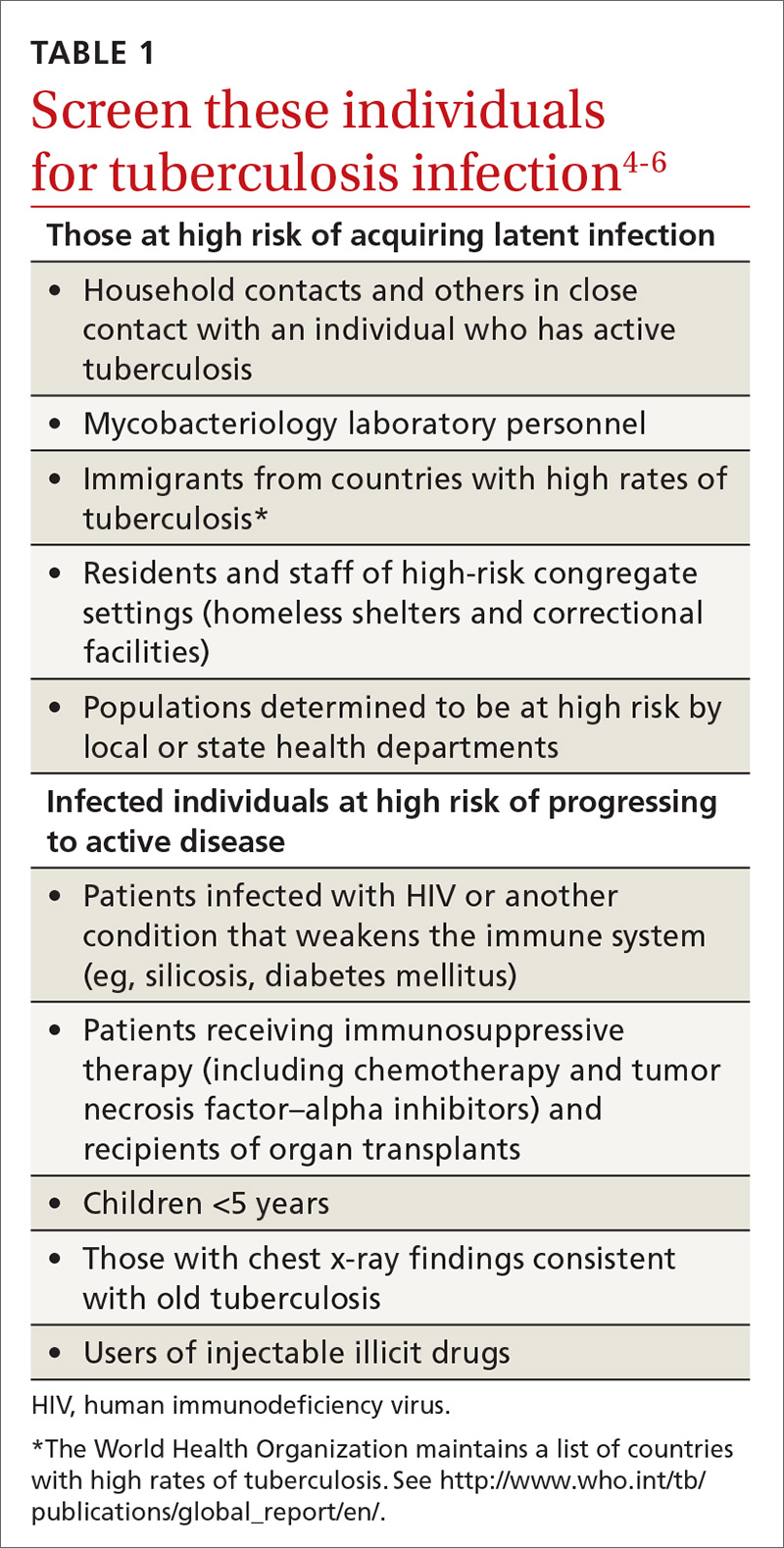

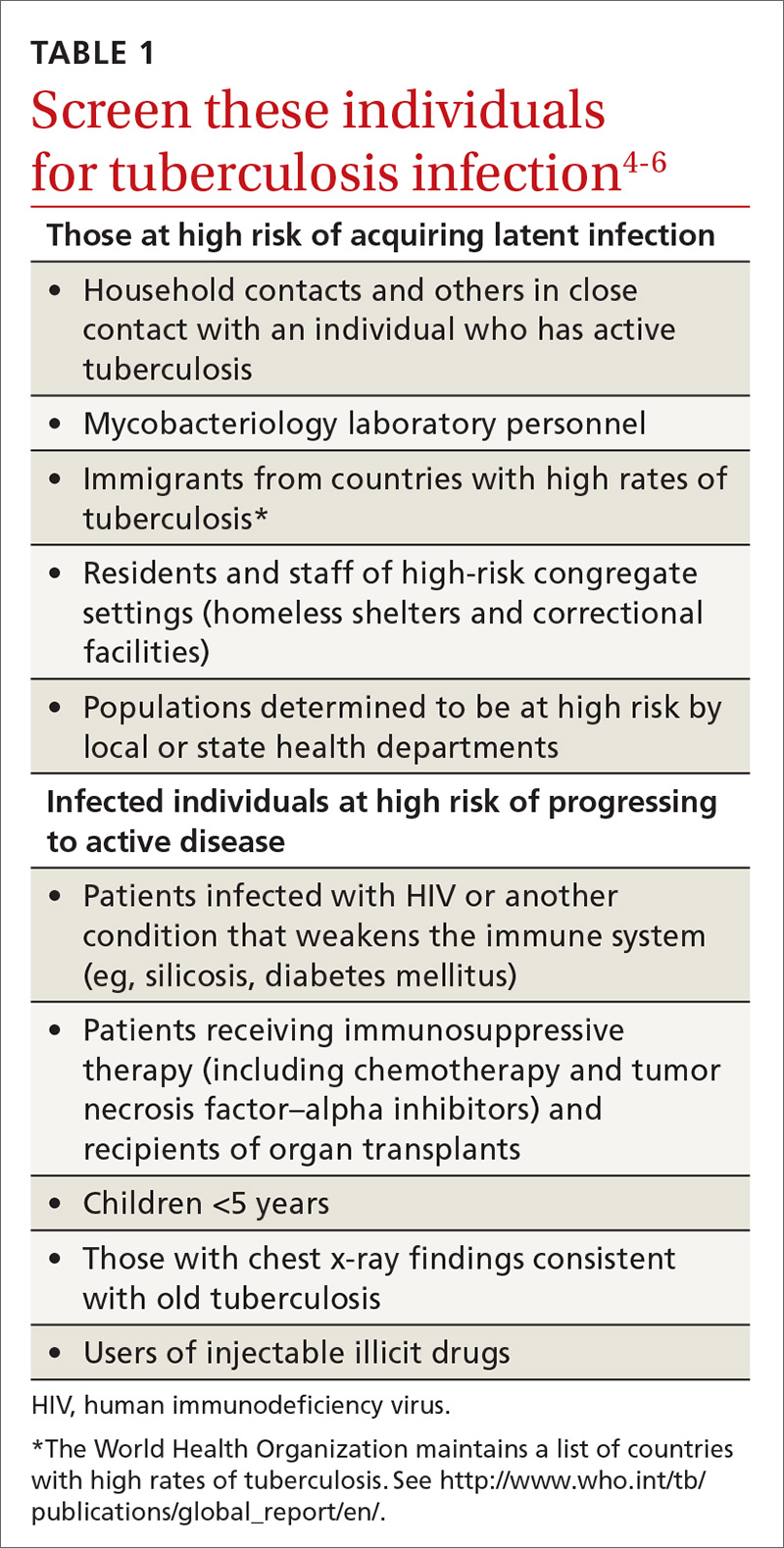

A major public health strategy for controlling TB in the United States is targeted screening for LTBI and treatment to prevent progression to active disease. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for LTBI in adults age 18 and older who are at high risk of TB infection.4 This is consistent with recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), although the CDC also recommends testing infants and children

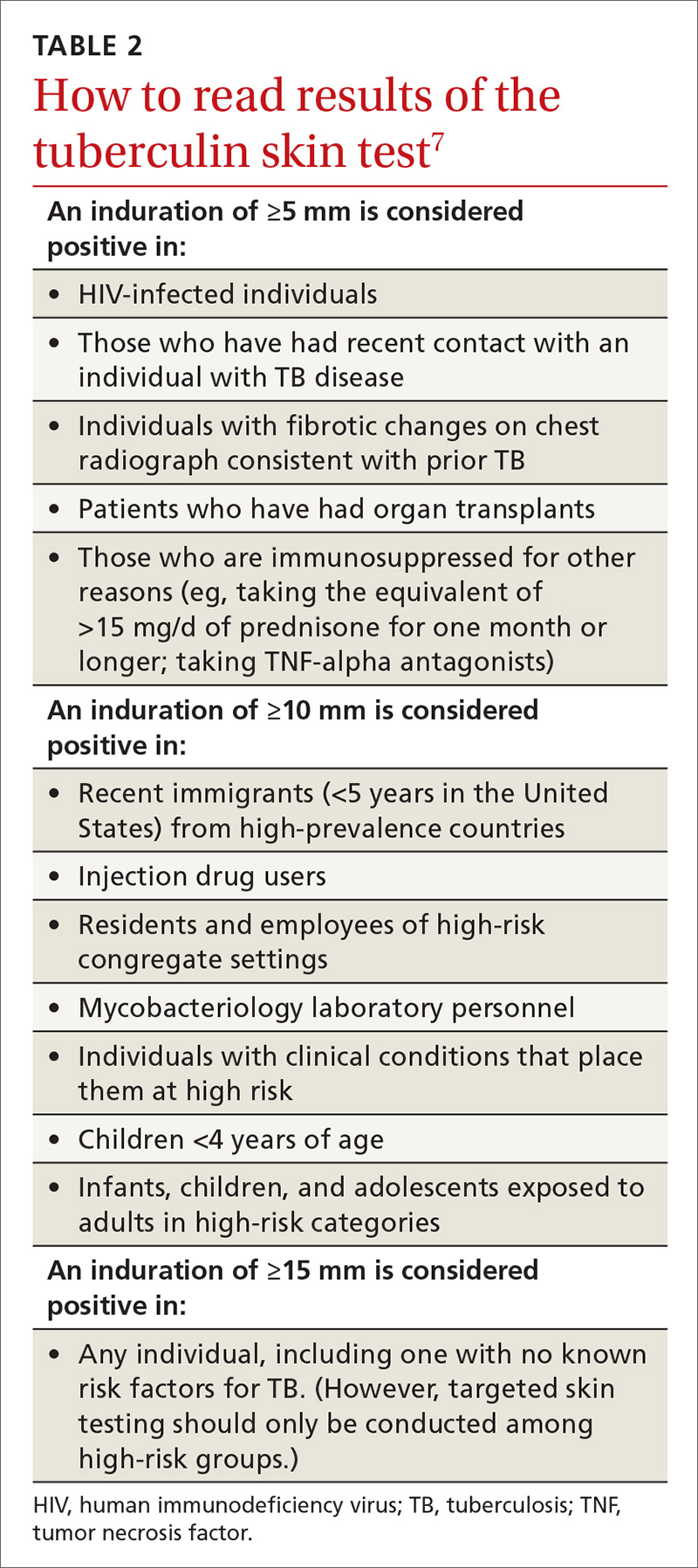

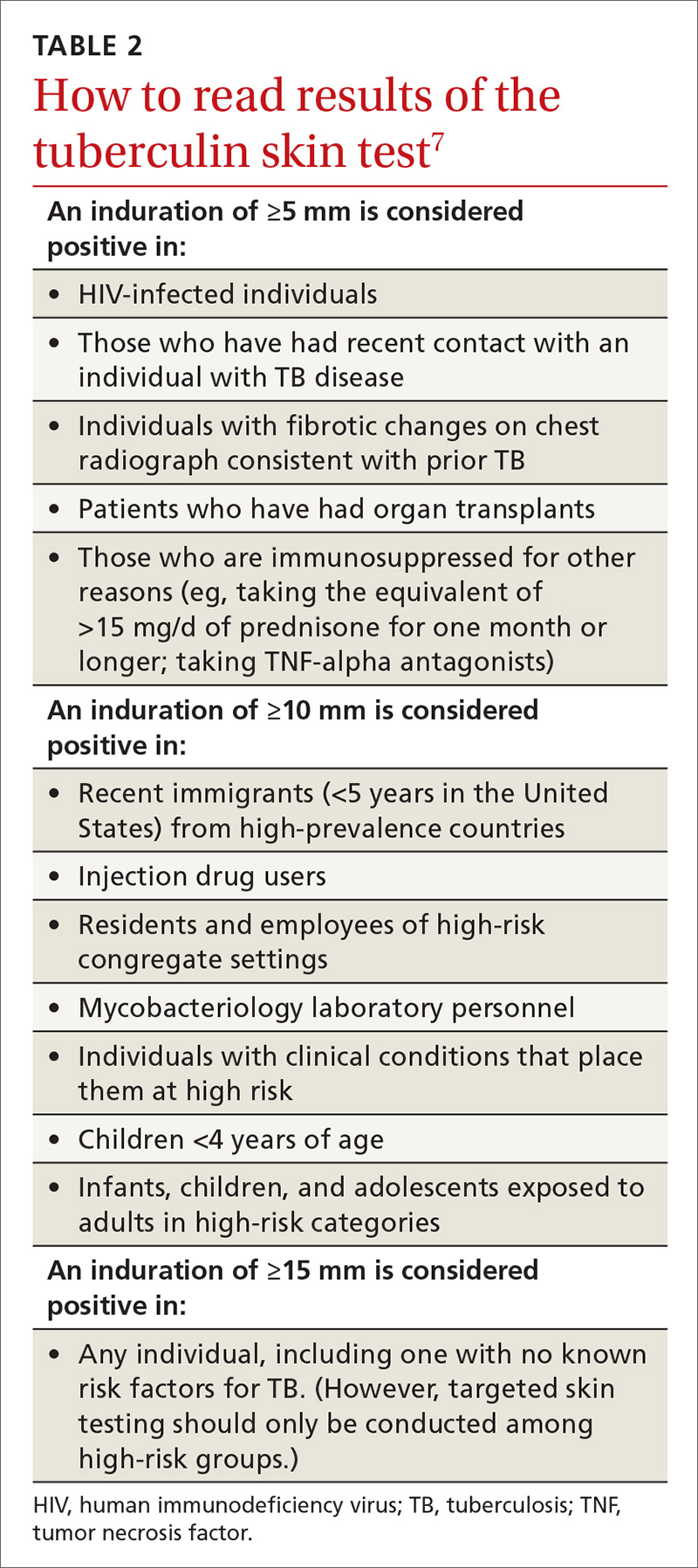

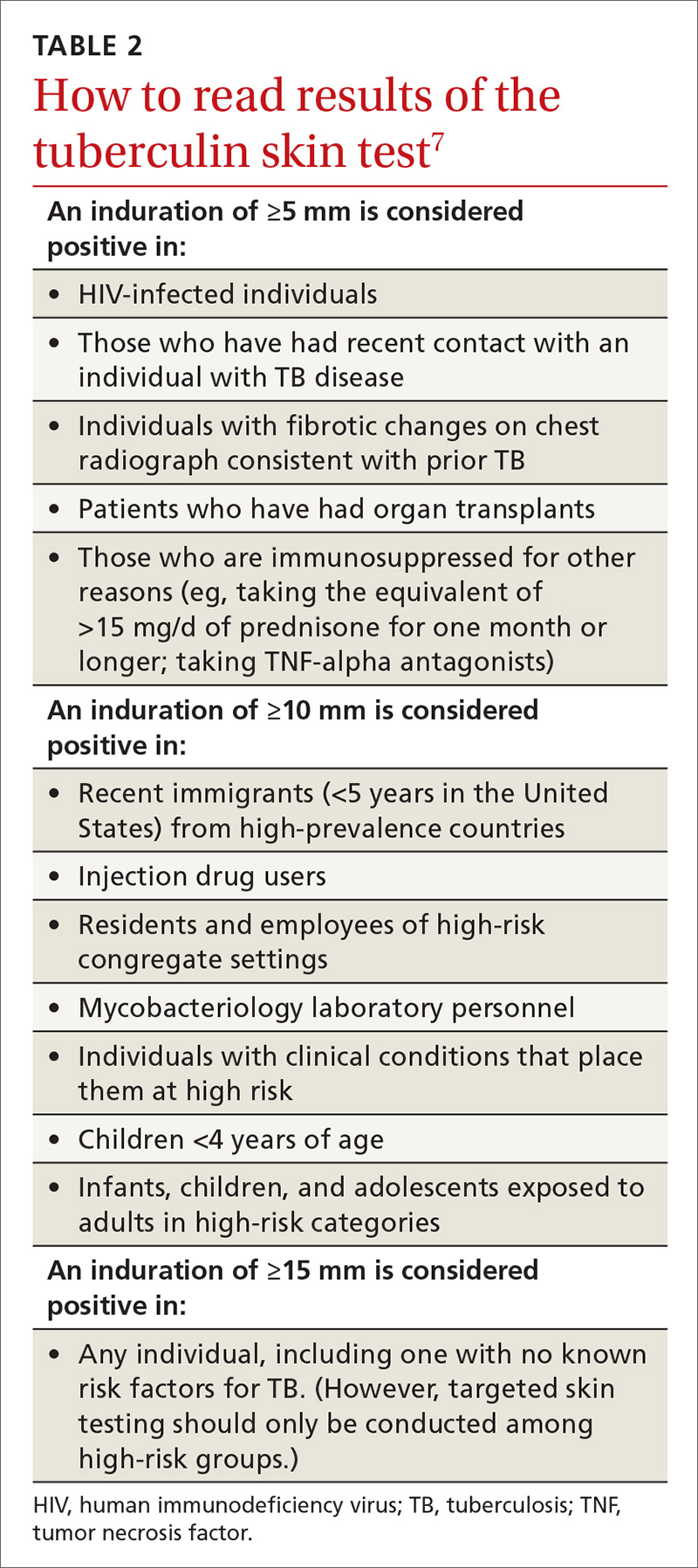

Two types of testing are available for TB screening: the TB skin test (TST) and the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA). There are 2 IGRA test options: T-SPOT. TB (Oxford Immunotec) and QuantiFERON-TB Gold (Qiagen). The TST and IGRA each has advantages and disadvantages. The TST must be placed intradermally and read correctly, and the patient must return for the interpretation 48 to 72 hours after placement. Test interpretation depends on the patient’s risk category, with either a 5-mm, 10-mm, or 15-mm induration being classified as a positive result (TABLE 27).

IGRA is a blood test that needs to be processed within a limited time frame and is more expensive than the TST. The USPSTF lists the sensitivity and specificity of each option as follows: TST, using a 10-mm cutoff, 79%, 97%; T-SPOT, 90%, 95%; QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube, 80%, 97%.4

Which test to use?

Recently the CDC, the American Thoracic Society, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America jointly published revised recommendations on TB testing:8

- For children younger than 5 years, TST is the preferred option, although IGRA is acceptable in children older than 3 years of age.

- For individuals at high risk of infection but not at high risk of disease progression, IGRA is recommended if they have received a bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine or are unlikely to return for TST interpretation.

- For others at high risk of infection but not at high risk of disease progression, IGRA is preferred but TST is acceptable.

- For those who have both a high risk of infection and a high risk of disease progression, evidence is insufficient to recommend one test over another; either type is acceptable.

- For those with neither high risk of infection nor high risk of disease progression, testing is not recommended. However, it may be required by law or for credentialing of some kind (eg, for some health professionals or those who work in schools or nursing homes). If this is the case, IGRA is suggested as the preferred test. If the test result is positive, performing a second test is advised (either TST or an alternative type of IGRA). Consider the individual to be infected only if the second test result is also positive.

If a TB screening result is positive, confirm or rule out active TB by asking about symptoms (cough, fever, weight loss) and performing a chest x-ray. If the radiograph shows signs of active TB, collect 3 sputum samples by induction for analysis by smear microscopy, culture, and, possibly, nucleic acid amplification and rifampin susceptibility testing. Consider consulting your local public health department for advice on, or assistance with, sample collection. Report LTBI to the local health department and seek advice on the appropriate tests and treatments.

Expanded treatment selections

With LTBI there are now 4 treatment options for patients and physicians to consider:9 isoniazid given daily or twice weekly for either 6 or 9 months; isoniazid and rifapentine given once weekly for 3 months; or rifampin given daily for 4 months. Factors influencing treatment selection include a patient’s age, concomitant conditions, and the likelihood of bacterial resistance. Free treatment for LTBI may be available; again, check with your local health department.

1. WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed November 8, 2017.

2. Schmit KM, Wansaula Z, Pratt R, et al. Tuberculosis—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:289-294.

3. Houben RMGJ, Dodd PJ. The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: a re-estimation using mathematical modelling. PLoS Med. 2016;13(10):e1002152. Available at: http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002152. Accessed November 10, 2017.

4. USPSTF. Screening for latent tuberculosis infection in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:962-969.

5. CDC. Tuberculosis. Who should be tested. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/testing/whobetested.htm. Accessed November 8, 2017.

6. CDC. Latent tuberculosis infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Targeted testing for tuberculosis. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/targetedtesting.htm#identifyingTBDisease. Accessed November 8, 2017.

7. CDC. TB elimination. Tuberculin skin testing. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/testing/skintesting.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2017.

8. Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, el al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of tuberculosis in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:111-115.

9. CDC. Treatment regimens for latent TB infection (LTBI). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm. Accessed November 8, 2017.

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a significant public health problem worldwide with an estimated 10.4 million new cases and 1.7 million deaths having occurred in 2016.1 In that same year, there were 9287 new cases in the United States—the lowest number of TB cases on record.2

TB appears in one of 2 forms: active disease, which causes symptoms, morbidity, and mortality and is a source of transmission to others; and latent TB infection (LTBI), which is asymptomatic and noninfectious but can progress to active disease. The estimated prevalence of LTBI worldwide is 23%,3 although in the United States it is only about 5%.4 The proportion of those with LTBI who will develop active disease is estimated at 5% to 10% and is highly variable depending on risks.4

In the United States, about two-thirds of active TB cases occur among those who are foreign born, whose rate of active disease is 14.6/100,000.2 Five countries account for more than half of foreign-born cases: Mexico, the Philippines, India, Vietnam, and China.2

Who should be tested?

A major public health strategy for controlling TB in the United States is targeted screening for LTBI and treatment to prevent progression to active disease. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for LTBI in adults age 18 and older who are at high risk of TB infection.4 This is consistent with recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), although the CDC also recommends testing infants and children

Two types of testing are available for TB screening: the TB skin test (TST) and the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA). There are 2 IGRA test options: T-SPOT. TB (Oxford Immunotec) and QuantiFERON-TB Gold (Qiagen). The TST and IGRA each has advantages and disadvantages. The TST must be placed intradermally and read correctly, and the patient must return for the interpretation 48 to 72 hours after placement. Test interpretation depends on the patient’s risk category, with either a 5-mm, 10-mm, or 15-mm induration being classified as a positive result (TABLE 27).

IGRA is a blood test that needs to be processed within a limited time frame and is more expensive than the TST. The USPSTF lists the sensitivity and specificity of each option as follows: TST, using a 10-mm cutoff, 79%, 97%; T-SPOT, 90%, 95%; QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube, 80%, 97%.4

Which test to use?

Recently the CDC, the American Thoracic Society, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America jointly published revised recommendations on TB testing:8

- For children younger than 5 years, TST is the preferred option, although IGRA is acceptable in children older than 3 years of age.

- For individuals at high risk of infection but not at high risk of disease progression, IGRA is recommended if they have received a bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine or are unlikely to return for TST interpretation.

- For others at high risk of infection but not at high risk of disease progression, IGRA is preferred but TST is acceptable.

- For those who have both a high risk of infection and a high risk of disease progression, evidence is insufficient to recommend one test over another; either type is acceptable.

- For those with neither high risk of infection nor high risk of disease progression, testing is not recommended. However, it may be required by law or for credentialing of some kind (eg, for some health professionals or those who work in schools or nursing homes). If this is the case, IGRA is suggested as the preferred test. If the test result is positive, performing a second test is advised (either TST or an alternative type of IGRA). Consider the individual to be infected only if the second test result is also positive.

If a TB screening result is positive, confirm or rule out active TB by asking about symptoms (cough, fever, weight loss) and performing a chest x-ray. If the radiograph shows signs of active TB, collect 3 sputum samples by induction for analysis by smear microscopy, culture, and, possibly, nucleic acid amplification and rifampin susceptibility testing. Consider consulting your local public health department for advice on, or assistance with, sample collection. Report LTBI to the local health department and seek advice on the appropriate tests and treatments.

Expanded treatment selections

With LTBI there are now 4 treatment options for patients and physicians to consider:9 isoniazid given daily or twice weekly for either 6 or 9 months; isoniazid and rifapentine given once weekly for 3 months; or rifampin given daily for 4 months. Factors influencing treatment selection include a patient’s age, concomitant conditions, and the likelihood of bacterial resistance. Free treatment for LTBI may be available; again, check with your local health department.

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a significant public health problem worldwide with an estimated 10.4 million new cases and 1.7 million deaths having occurred in 2016.1 In that same year, there were 9287 new cases in the United States—the lowest number of TB cases on record.2

TB appears in one of 2 forms: active disease, which causes symptoms, morbidity, and mortality and is a source of transmission to others; and latent TB infection (LTBI), which is asymptomatic and noninfectious but can progress to active disease. The estimated prevalence of LTBI worldwide is 23%,3 although in the United States it is only about 5%.4 The proportion of those with LTBI who will develop active disease is estimated at 5% to 10% and is highly variable depending on risks.4

In the United States, about two-thirds of active TB cases occur among those who are foreign born, whose rate of active disease is 14.6/100,000.2 Five countries account for more than half of foreign-born cases: Mexico, the Philippines, India, Vietnam, and China.2

Who should be tested?

A major public health strategy for controlling TB in the United States is targeted screening for LTBI and treatment to prevent progression to active disease. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for LTBI in adults age 18 and older who are at high risk of TB infection.4 This is consistent with recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), although the CDC also recommends testing infants and children

Two types of testing are available for TB screening: the TB skin test (TST) and the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA). There are 2 IGRA test options: T-SPOT. TB (Oxford Immunotec) and QuantiFERON-TB Gold (Qiagen). The TST and IGRA each has advantages and disadvantages. The TST must be placed intradermally and read correctly, and the patient must return for the interpretation 48 to 72 hours after placement. Test interpretation depends on the patient’s risk category, with either a 5-mm, 10-mm, or 15-mm induration being classified as a positive result (TABLE 27).

IGRA is a blood test that needs to be processed within a limited time frame and is more expensive than the TST. The USPSTF lists the sensitivity and specificity of each option as follows: TST, using a 10-mm cutoff, 79%, 97%; T-SPOT, 90%, 95%; QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube, 80%, 97%.4

Which test to use?

Recently the CDC, the American Thoracic Society, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America jointly published revised recommendations on TB testing:8

- For children younger than 5 years, TST is the preferred option, although IGRA is acceptable in children older than 3 years of age.

- For individuals at high risk of infection but not at high risk of disease progression, IGRA is recommended if they have received a bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine or are unlikely to return for TST interpretation.

- For others at high risk of infection but not at high risk of disease progression, IGRA is preferred but TST is acceptable.

- For those who have both a high risk of infection and a high risk of disease progression, evidence is insufficient to recommend one test over another; either type is acceptable.

- For those with neither high risk of infection nor high risk of disease progression, testing is not recommended. However, it may be required by law or for credentialing of some kind (eg, for some health professionals or those who work in schools or nursing homes). If this is the case, IGRA is suggested as the preferred test. If the test result is positive, performing a second test is advised (either TST or an alternative type of IGRA). Consider the individual to be infected only if the second test result is also positive.

If a TB screening result is positive, confirm or rule out active TB by asking about symptoms (cough, fever, weight loss) and performing a chest x-ray. If the radiograph shows signs of active TB, collect 3 sputum samples by induction for analysis by smear microscopy, culture, and, possibly, nucleic acid amplification and rifampin susceptibility testing. Consider consulting your local public health department for advice on, or assistance with, sample collection. Report LTBI to the local health department and seek advice on the appropriate tests and treatments.

Expanded treatment selections

With LTBI there are now 4 treatment options for patients and physicians to consider:9 isoniazid given daily or twice weekly for either 6 or 9 months; isoniazid and rifapentine given once weekly for 3 months; or rifampin given daily for 4 months. Factors influencing treatment selection include a patient’s age, concomitant conditions, and the likelihood of bacterial resistance. Free treatment for LTBI may be available; again, check with your local health department.

1. WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed November 8, 2017.

2. Schmit KM, Wansaula Z, Pratt R, et al. Tuberculosis—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:289-294.

3. Houben RMGJ, Dodd PJ. The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: a re-estimation using mathematical modelling. PLoS Med. 2016;13(10):e1002152. Available at: http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002152. Accessed November 10, 2017.

4. USPSTF. Screening for latent tuberculosis infection in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:962-969.

5. CDC. Tuberculosis. Who should be tested. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/testing/whobetested.htm. Accessed November 8, 2017.

6. CDC. Latent tuberculosis infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Targeted testing for tuberculosis. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/targetedtesting.htm#identifyingTBDisease. Accessed November 8, 2017.

7. CDC. TB elimination. Tuberculin skin testing. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/testing/skintesting.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2017.

8. Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, el al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of tuberculosis in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:111-115.

9. CDC. Treatment regimens for latent TB infection (LTBI). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm. Accessed November 8, 2017.

1. WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2017. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available at: http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed November 8, 2017.

2. Schmit KM, Wansaula Z, Pratt R, et al. Tuberculosis—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:289-294.

3. Houben RMGJ, Dodd PJ. The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: a re-estimation using mathematical modelling. PLoS Med. 2016;13(10):e1002152. Available at: http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002152. Accessed November 10, 2017.

4. USPSTF. Screening for latent tuberculosis infection in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:962-969.

5. CDC. Tuberculosis. Who should be tested. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/testing/whobetested.htm. Accessed November 8, 2017.

6. CDC. Latent tuberculosis infection: a guide for primary health care providers. Targeted testing for tuberculosis. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/ltbi/targetedtesting.htm#identifyingTBDisease. Accessed November 8, 2017.

7. CDC. TB elimination. Tuberculin skin testing. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/testing/skintesting.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2017.

8. Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, el al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of tuberculosis in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:111-115.

9. CDC. Treatment regimens for latent TB infection (LTBI). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/treatment/ltbi.htm. Accessed November 8, 2017.

From The Journal of Family Practice | 2017;66(12):755-757.