User login

- Physician “self-doctoring” may have benefits, but it may also cause unanticipated psychological and medical problems. When faced with a serious medical problem, carefully assess both the potential positive and negative aspects of such behavior.

Background: Self-doctoring is providing oneself care normally delivered by a professional caregiver. Expert authors warn physicians not to self-doctor, yet cross-sectional studies document that physicians frequently do. Explanations for this disparity remain speculative.

Objective: To better understand the circumstances when physicians did and did not doctor themselves and the reasoning behind their actions.

Design: Qualitative semistructured interview study of 23 physician-patients currently or previously treated for cancer.

Results: Participants had multiple opportunities to doctor themselves (or not) at each stage of illness. Only 1 physician recommended self-doctoring, although most reported having done so, sometimes without realizing it. Participants’ approaches to their own health care created a continuum ranging between typical physician and patient roles. Participants emphasizing their physician role approached their health care as they would approach the care of their own patients, preferring convenience and control of their care to support from professional caregivers. Participants emphasizing their role as patient approached their health care as they thought a patient should, preferring to rely less on their own abilities and more on their providers, whose support they valued. Most participants balanced both roles depending on their experiences and basic issues of trust and control. Importantly, subjects at both ends of the continuum reported unanticipated pitfalls of their approach.

Conclusion: Our findings showed that participants’ health care-seeking strategies fell on a continuum that ranged from a purely patient role to one that centered on physician activities. Participants identified problems associated with overdependence on either role, suggesting that a balanced approach, one that uses the advantages of both physician and patient roles, has merit.

The physician who doctors himself has a fool for a patient.

—Sir William Osler

The consistent message in the medical literature, beginning with Osler, has been that physicians should not doctor themselves.1-9 Despite this belief, a number of cross-sectional studies suggest that at best only 50% of physicians even have a personal physician1,8-13 and that between 42% and 82% of physicians doctor themselves in some fashion.1,6,8,12

Becoming a competent physician does not automatically make one a competent patient.14,15 In fact, physicians are allegedly the “very worst patients.”15 Physicians are expected to understand and empathize with the patient’s perspective, yet most authors have maintained that physicians tend to avoid, deny, or reject patient-hood,2,3,5,11,13,14,16-22 and even the susceptibility to illness.23

Given the high prevalence of self-doctoring behavior among physician-patients, we sought to further explore seriously ill physicians’ experiences with self-doctoring. Specifically, we wanted to know if they doctored themselves and, if so, when, why, and with what outcome.

Methods

Design

For this qualitative study, approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board, we used semistructured in-depth interviews.

Study population and sampling

A convenience sample of physicians who had been treated for cancer during or after their medical training was identified by clinicians in the divisions of oncology and radiation oncology at our institution. Of 38 physicians contacted, 25 agreed to participate; however, 2 subjects died before their interview could be arranged. Enrollment continued until no new concepts were identified, also called the point of theoretical saturation.24

Data collection

We based the interview questions on themes extracted from a literature search that identified 5 books, 26 articles, and 3 videotapes. (These references are available online as Table W1.) Interviews lasted approximately 1.5 hours. The interviewer (E.F.) started by asking subjects to tell the story of how they learned of their cancer and progressed to more focused questions about whether they acted as their own doctor and why. All interviews were taped and transcribed, and their accuracy was verified by listening to the audiotape.

Analysis. Two coders (E.F. and R.H.) independently coded all 23 transcripts. In case of disagreement, the coders achieved consensus through discussion and used this information to refine the boundaries of each theme.

Working together, we created a comprehensive coding scheme by arranging data into logical categories of themes using the strategies of textual analysis and codebook development described by Crabtree and Miller.25 The work by Crabtree and Miller addressed the theme “health care-seeking behaviors and strategies” and its associated codes developed using an “editing-style analysis” consistent with the constant comparative method in the Grounded Theory tradition.26

Trustworthiness. To ensure trustworthiness, we mailed an 11-item summary of the main points to the 21 surviving participants as the analysis neared completion. We asked them to review the main points of our study, indicate whether they agreed or disagreed (with no response indicating agreement), and add any clarifying comments they felt appropriate. This information was used to clarify and further develop themes.

RESULTS

Our sample was predominately Caucasian and represented a diversity of gender, specialty, and participant characteristics (Table 1).

TABLE 1

Participant characteristics (N=23)

| Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean and median=55, range=28–83 | |

| Years in practice | Mean=22.4, median=19, range=0–56 (1 resident, 1 fellow, 2 retired) | |

| Sex (n/N) | Male 13/23 | |

| Ethnicity (n) | 19 Caucasian, 3 Asian, 1 African American | |

| Specialty | Family practice/internal medicine: 5 | |

| Adult subspecialist: 4 | ||

| Pediatrics/child subspecialist: 6 | ||

| Surgical specialty: 3 | ||

| Neurology/anesthesia/emergency medicine/radiation oncology: 5 | ||

| Practice type | Clinician: 10 | Clinician/researcher: 5 |

| Clinician/educator: 5 | Clinician/administrator: 3 | |

| Practice location | University hospital: 11 | |

| Community hospital: 2 | ||

| Private practice: 9 | ||

| Research/nonpracticing: 1 | ||

| Tumor type | Breast: 5; renal: 4; prostate: 5; lymphoma: 3; colon: 2 (1 participant had 2 cancers) | |

| Bone/brain/larynx/head & neck/thyroid: 1 each | ||

| Illness stage | Disease-free >5 years: 9 | |

| Disease-free >6 months: 5 | ||

| Disease-free <6 months: 4 | ||

| In treatment: 2 | ||

| Metastatic/rapidly progressive disease: 3 | ||

The nature of self-doctoring What is self-doctoring and when does it occur?

The participants did not identify a discrete activity or group of activities that constituted self-doctoring (Table 2). Some activities were obvious because they required privileges restricted to medical personnel—for example, ordering one’s own abdominal computed tomography scan. Other activities were less obvious because they could be performed by any patient—such as treating oneself for a minor illness like low back pain.

Should you doctor yourself? Whereas only 1 participant recommended self-doctoring, the rest were more or less strongly opposed to the practice. Despite this stance, most participants were able to identify instances during which they did doctor themselves. Sometimes they doctored themselves without acknowledging this activity as doctoring.

EF: Do you ever feel like you do anything where you doctor yourself?

PARTICIPANT: No I don’t think so . . . I’ve never had a primary care physician, which is probably a mistake because I tell all my patients they should have one.

EF: How did you get your PSAs [prostate-specific antigen]?

PARTICIPANT: I would just go down and get my blood done myself.

EF: So would you say that is an example of being your own doctor?

PARTICIPANT: Yeah, I suppose it is to some degree!

Reframing the question: from self-doctoring to health care-seeking strategies. Although our questions were about self-doctoring, participants spoke less about self-doctoring and more about their strategy for obtaining health care. This concept of health care-seeking strategies accounted for all of the various methods that participants used to obtain health care, of which self-doctoring was one.

TABLE 2

Subtle ways in which participants doctored themselves

| Decide when to seek or not seek care |

| Did not get alarmed about neck mass because she knew what cancer felt like |

| Did not call physician with most things because they are “silly” |

| Did not go to physician until family member insisted |

| Establish a diagnosis |

| Broke own bad news by going into the hospital computer on a weekend |

| Diagnosed self as depressed but that it was subclinical |

| Went directly to a gastroenterologist to evaluate abdominal pain |

| Called physician with a diagnosis, not a problem |

| Learn about illness |

| Became an expert in own disease |

| Called an expert colleague at another institution to critique care |

| Influence care decisions |

| Rejected a recommendation that did not coincide with medical training |

| Decided on a specific surgical procedure, then found an oncologist |

| Chose a physician who she knew would go along with whatever she wanted |

| Assumed he didn’t need a second opinion because he was a physician |

| Get treatment |

| Managed only illnesses in her own specialty |

| Followed own Dilantin levels |

The continuum of health care-seeking strategies

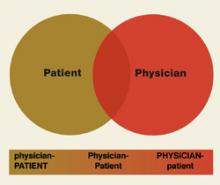

The following examples illustrate 3 health care-seeking strategies. When viewed together, these strategies create a continuum ranging between the roles of physician and patient. The following categories are not intended to be mutually exclusive, but to indicate an individual participant’s emphasized role. We referred to strategies that emphasized the physician role as PHYSICIAN-patient, here exemplified by this internist who had more than 40 years of experience in clinical practice.

One evening I felt a mass in my right lower quadrant. I figured I had a little hematoma—I couldn’t see anything, but I was pretty asymptomatic and by chance felt [the mass]. I watched it for maybe a week or so and it didn’t seem to change. I did a couple of routine blood tests and my CBC and Chem-20 profile were okay. But then when [the mass] didn’t go down, I asked one of my partners to feel it. He said “yes, I can feel a mass—you’d better look into it.” I didn’t see a doctor—just a curbside-type thing. So then I set up a CT scan, I got a CE antigen, and I just did this on my own, and the CT scan showed a mass in the appendiceal area and the CE antigen was up a little bit. I guess I went right to my surgeon!

At the other end of the continuum, this middleaged pediatric subspecialist represents those physicians whose health care-seeking strategies were based on their roles as patients. We labeled this strategy physician-PATIENT, emphasizing the patient role.

You know, I think that a physician diagnosed with cancer is like any person diagnosed with cancer. Their first concern has nothing to do with their careers. I think the hardest thing about being a physician-patient is that you hate to bother your doctors. Or you want to sort of “call your doctor with the answer” instead of just asking questions. I think you sort of feel like sometimes that you should be able to somehow know whether [your] symptom is related to metastatic disease without having to ask, “Should I be worried about this or not?” Physicians have the same fears and difficulties as anyone else does and need to give themselves permission to act like a normal patient.

This next physician, a medical subspecialist who had recently undergone bilateral mastectomy for stage I breast cancer, falls somewhere in the middle of this continuum. We labeled this approach Physician-Patient, signifying the incorporation of both roles into her health care-seeking strategy.

This breast mass was discovered by my gynecologist but he told me, don’t worry—it’s a fibroadenoma. It was small, not really moveable, so I didn’t listen to him. I went to a surgeon. I wouldn’t say I doctored myself just because I didn’t necessarily listen to my physician. It didn’t make sense from my medical training, so I did what made sense—I can listen to those doctors’ advice, but I use my own judgment.

Advantages of being a physician-patient: convenience and control. Physicians recognized definite advantages afforded by their status, mostly related to added convenience in navigating through the system and scheduling appointments, and being able to control many aspects of their care. This specialist in infectious disease with metastatic cancer illustrates the importance of convenience and control in explaining why she often relied on self-doctoring.

I think idealistically you should never be your own doctor, but realistically I think I can accomplish more faster without interrupting the doctor’s schedule. A couple of weeks ago I started spiking fevers but I had no symptoms of any kind…. After the third day I thought, “I bet this is tumor fever!” So I went out and bought Naprosyn and I was afebrile the next morning…. Now I guess there is a small chance I have an abscess somewhere, but I think I can obviate a lot of workup that my physician is more obligated to do than I am, medico-legally … I am sure there are control issues because we all like control and I am sure I like the control and the convenience.

Disadvantages of being a physician-patient: denying yourself the opportunity to receive support; lack of objectivity; delaying care. In talking about the disadvantages of their strategies, physicians invariably referred to a previous negative experience. This young pediatrician with a large retroperitoneal mass described how she learned of her computed tomography scan results.

More insidious is the potential loss of objectivity that can occur when one’s own health is at stake. For example, a pediatric subspecialist with lymphoma described how she rationalized not bringing the enlarged lymph nodes in her neck to medical attention by telling herself that she “knew what cancer felt like.”

Advantages of being a physician-patient: trusting one’s care to others; relinquishing control; benefiting from the expertise and support of other physicians. Physicians who relied more on their physicians and less on self-doctoring approached control from the perspective of “letting go.” This emergency medicine specialist explains why he would rather trust his physician’s expertise than his own.

Find doctors you trust and listen to them because they’re the experts. The same way you’re the expert to your patients, the patients you care for. In some real sense, relinquish control. Give control to somebody else and even for nonphysician patients it’s very difficult but for physician-patients I think it’s one of the most difficult things but you have to do this. You have to trust yourself to someone else.

Disadvantages of being a physician-patient: being too trusting. This physician-patient describes adopting a more passive stance toward his health care in order to “be a good patient.” The result was that his Hodgkin’s disease was not diagnosed until 18 months after his initial biopsy.

By adopting that stance, I might have done myself a disservice. Our lives would have been very different had I questioned more aggressively the use of a needle biopsy because the pathologist here said, “You know, that’s an absolutely foolish inept way to look for lymphoma.” So in some ways the strategy backfired a bit.… But I really trusted their judgment.

Discussion

The attitudes and experiences of the study participants paralleled the medical literature: all but 1 recommended against self-doctoring, yet almost all were able to identify situations in which they did doctor themselves. Our findings show that participants’ health care-seeking strategies can be identified along a continuum ranging between the roles of physician and patient ( Figure 1 ). Whereas previous literature on physician-patients has characterized their situation as “role-reversal,”16,19,27 our findings suggest that physicians assume both roles depending on circumstances, influenced by their desire for control and degree of trust.

Trusting health care may be particularly difficult for physician-patients.2,3,27 In our study, participants at the “physician” end of the continuum were reluctant to “let go” of control over care, especially care they did not trust. They valued the convenience and time saved when they did things themselves and felt less need for support from their professional caregivers. These physicians did not consciously set out to doctor themselves. Instead, they simply used the expertise and status of their physician role to take care of themselves in the same way they might take care of a patient.

At the “patient” end of the health care-seeking continuum, participants approached their own health care as they thought a patient should. They tended not to be as involved with the details of their care, felt less pressure to be an expert in their own illness, and wanted their doctor to play an active role in medical decisions. They frequently emphasized the importance of being able to trust their care to another person and letting go of the need to be in control of their care. They valued the relationships with their physicians and appreciated the support these relationships provided.

Negative experiences invariably changed participants’ attitudes and where they were identified on the continuum. Both roles included unanticipated pitfalls, particularly for participants who adhered rigidly to either end of the continuum.

This study had important limitations. We recruited only physician-patients with cancer from a single institution and our sample was skewed toward survivors and presumably toward individuals who were comfortable talking about their experiences. Moreover, we replied on a convenience sample of patient-physicians identified by their specialists. Thus, the transferability of out findings ma be limited. Finally, our data captured the perspective of only the “physician-patient”—we did not interview their physicians. Nonetheless, we believe this provides robust new insights into physicians self-doctoring behaviors in the face of a serious, life-threatening illness.

Our findings make sense of the apparent mismatch between expert recommendations and physicians’ stated beliefs on one side, and physicians’ reported activities on the other. Rather than warning physicians not to doctor themselves, we advocate trying to focus on what is important: obtaining and providing good care ( Table 3 ). These questions are derived from 1 or more participating physician-patients’ experiences. In this way, we hope that readers might benefit from our participants’ experiences.

TABLE 3

Questions for physicians to ask themselves when seeking health care

| Are you responding more like a patient or more like a physician? Why? |

| If you are responding more like a physician: |

| Is it out of habit or convenience? |

| Is it because you don’t trust your doctors or health system (or because they are untrustworthy)? |

| Are you using your role as physician to shield yourself from painful or overwhelming realities? |

| Was an error made, or were you not getting the care you thought necessary? |

| AND |

| Do you have, or can you get, the necessary expertise to deal with your illness? |

| Are you too emotionally involved to be objective (and how would you recognize this problem)? |

| Do you, at minimum, have a physician you can trust and collaborate with—one with whom you would feel comfortable being a patient? |

| Are you getting the psychosocial support that may help you? |

| Are your nonmedical needs (rest, recreation, time off, decreased responsibilities at work) being met? |

| Are you getting the care you would want a patient in your position to receive? |

| If you are responding more like a patient: |

| Is it because you want to be “a good patient”? |

| Is it because you want someone else to make your decisions for you? |

| AND |

| Do you trust your professional caregivers and health care system? (And is that trust well founded?) |

| Are you ignoring your medical training or instincts because you do not want to offend? |

| Are you getting the information that you need (especially informed consent)? |

| Are you getting the psychosocial support you need? |

| Are your nonmedical needs (rest, recreation, time off, decreased responsibilities at work) being met? |

| Is the care you are getting consistent with the standard of care? |

| If it is not, do you understand why? |

| Are you getting the respect you would want a patient in your position to receive? |

| In either case: Would you be better off responding more like a patient, or more like a physician? |

FIGURE 1

Physician-patient continuum

Acknowledgments

Dr Carrese was a Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar when this work was conducted. This work was largely completed while Drs Fromme and Hebert were fellows in the Division of General Internal Medicine, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. It was presented in abstract form at the 24th Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, San Diego, California in May 2001 and was funded by a grant from the Kenneth B. Schwartz Center, Boston, Mass.

Corresponding author

Erik K. Fromme, MD, Division of General Medicine and Geriatrics, L475, Oregon Health and Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road, Portland, OR 97239-3098. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Toyry S, Rasanen K, Kujala S, et al. Self-reported health, illness and self-care among Finnish physicians: a national survey. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1079-1085.

2. Allibone A. Who treats the doctor? Practitioner. 1990;234:984-987.

3. Miller MN, McGowen KR. The painful truth: physicians are not invincible. South Med J. 2000;93:966-973.

4. Budge A, Dickstein E. The doctor as patient: bioethical dilemmas reflected in literary narratives. Lit Med. 1988;7:132-137.

5. Rogers T. Barriers to the doctor as patient role. A cultural construct. Aust Fam Physician. 1998;27:1009-1013.

6. Waldron HA. Sickness in the medical profession. Ann Occup Hyg. 1996;40:391-396.

7. Waldron HA. Medical advice for sick physicians. Lancet. 1996;347:1558-1559.

8. Wines AP, Khadra MH, Wines RD. Surgeon, don’t heal thyself: a study of the health of Australian urologists. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998;68:778-781.

9. Pullen D, Lonie CE, Lyle DM, Cam DE, Doughty MV. Medical care of doctors. Med J Aust. 1995;162:481,-484.

10. Allibone A, Oakes D, Shannon HS. The health and health care of doctors. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1981;31:728-734.

11. Schwartz JS, Lewis CE, Clancy C, Kinosian MS, Radany MH, Koplan JP. Internists’ practices in health promotion and disease prevention. A survey. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:46-53.

12. Rosen IM, Christie JD, Bellini LM, Asch DA. Health and health care among housestaff in four U.S. internal medicine residency programs. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:116-121.

13. Kahn KL, Goldberg RJ, DeCosimo D, Dalen JE. Health maintenance activities of physicians and nonphysicians. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:2433-2436.

14. Robbins GF, MacDonald MC, Pack GT. Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of physicians with cancer. Cancer 1953;6:624-626.

15. Anonymous [proverb] Strauss’ Familiar Medical Quotations. New York, NY: Little, Brown; 1968;415b.-

16. Spiro HM, Mandell H. When doctors get sick. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:152-154.

17. Bittker TE. Reaching out to the depressed physician. JAMA. 1976;236:1713-1716.

18. Lampert PH. On the other side of the bed sheets. When the doctor is the patient. Minn Med. 1991;74(11):14-19.

19. Glass GS. Incomplete role reversal: the dilemma of hospitalization for the professional peer. Psychiatry. 1975;38:132-144.

20. Ellard J. The disease of being a doctor. Med J Aust. 1974;2:318-323.

21. Vaillant GE, Sobowale NC, McArthur C. Some psychologic vulnerabilities of physicians. N Engl J Med. 1972;287:372-375.

22. Thompson WT, Cupples ME, Sibbett CH, Skan DI, Bradley T. Challenge of culture, conscience, and contract to general practitioners’ care of their own health: qualitative study. BMJ. 2001;323:728-731.

23. Gold N. The doctor, his illness and the patient. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1972;6:209-213.

24. Kuzel A. Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In: Crabtree B, Miller W, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1992;31-44.

25. Crabtree B, Miller W. A template approach to text analysis: developing and using codebooks. In: Crabtree B, Miller W, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1992;93-109.

26. Glaser B, Strauss A. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine De Gruyter; 1967;101-115.

27. Edelstein EL, Baider L. Role reversal: when doctors become patients. Psychiatria Clin (Basel). 1982;15:177-183.

- Physician “self-doctoring” may have benefits, but it may also cause unanticipated psychological and medical problems. When faced with a serious medical problem, carefully assess both the potential positive and negative aspects of such behavior.

Background: Self-doctoring is providing oneself care normally delivered by a professional caregiver. Expert authors warn physicians not to self-doctor, yet cross-sectional studies document that physicians frequently do. Explanations for this disparity remain speculative.

Objective: To better understand the circumstances when physicians did and did not doctor themselves and the reasoning behind their actions.

Design: Qualitative semistructured interview study of 23 physician-patients currently or previously treated for cancer.

Results: Participants had multiple opportunities to doctor themselves (or not) at each stage of illness. Only 1 physician recommended self-doctoring, although most reported having done so, sometimes without realizing it. Participants’ approaches to their own health care created a continuum ranging between typical physician and patient roles. Participants emphasizing their physician role approached their health care as they would approach the care of their own patients, preferring convenience and control of their care to support from professional caregivers. Participants emphasizing their role as patient approached their health care as they thought a patient should, preferring to rely less on their own abilities and more on their providers, whose support they valued. Most participants balanced both roles depending on their experiences and basic issues of trust and control. Importantly, subjects at both ends of the continuum reported unanticipated pitfalls of their approach.

Conclusion: Our findings showed that participants’ health care-seeking strategies fell on a continuum that ranged from a purely patient role to one that centered on physician activities. Participants identified problems associated with overdependence on either role, suggesting that a balanced approach, one that uses the advantages of both physician and patient roles, has merit.

The physician who doctors himself has a fool for a patient.

—Sir William Osler

The consistent message in the medical literature, beginning with Osler, has been that physicians should not doctor themselves.1-9 Despite this belief, a number of cross-sectional studies suggest that at best only 50% of physicians even have a personal physician1,8-13 and that between 42% and 82% of physicians doctor themselves in some fashion.1,6,8,12

Becoming a competent physician does not automatically make one a competent patient.14,15 In fact, physicians are allegedly the “very worst patients.”15 Physicians are expected to understand and empathize with the patient’s perspective, yet most authors have maintained that physicians tend to avoid, deny, or reject patient-hood,2,3,5,11,13,14,16-22 and even the susceptibility to illness.23

Given the high prevalence of self-doctoring behavior among physician-patients, we sought to further explore seriously ill physicians’ experiences with self-doctoring. Specifically, we wanted to know if they doctored themselves and, if so, when, why, and with what outcome.

Methods

Design

For this qualitative study, approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board, we used semistructured in-depth interviews.

Study population and sampling

A convenience sample of physicians who had been treated for cancer during or after their medical training was identified by clinicians in the divisions of oncology and radiation oncology at our institution. Of 38 physicians contacted, 25 agreed to participate; however, 2 subjects died before their interview could be arranged. Enrollment continued until no new concepts were identified, also called the point of theoretical saturation.24

Data collection

We based the interview questions on themes extracted from a literature search that identified 5 books, 26 articles, and 3 videotapes. (These references are available online as Table W1.) Interviews lasted approximately 1.5 hours. The interviewer (E.F.) started by asking subjects to tell the story of how they learned of their cancer and progressed to more focused questions about whether they acted as their own doctor and why. All interviews were taped and transcribed, and their accuracy was verified by listening to the audiotape.

Analysis. Two coders (E.F. and R.H.) independently coded all 23 transcripts. In case of disagreement, the coders achieved consensus through discussion and used this information to refine the boundaries of each theme.

Working together, we created a comprehensive coding scheme by arranging data into logical categories of themes using the strategies of textual analysis and codebook development described by Crabtree and Miller.25 The work by Crabtree and Miller addressed the theme “health care-seeking behaviors and strategies” and its associated codes developed using an “editing-style analysis” consistent with the constant comparative method in the Grounded Theory tradition.26

Trustworthiness. To ensure trustworthiness, we mailed an 11-item summary of the main points to the 21 surviving participants as the analysis neared completion. We asked them to review the main points of our study, indicate whether they agreed or disagreed (with no response indicating agreement), and add any clarifying comments they felt appropriate. This information was used to clarify and further develop themes.

RESULTS

Our sample was predominately Caucasian and represented a diversity of gender, specialty, and participant characteristics (Table 1).

TABLE 1

Participant characteristics (N=23)

| Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean and median=55, range=28–83 | |

| Years in practice | Mean=22.4, median=19, range=0–56 (1 resident, 1 fellow, 2 retired) | |

| Sex (n/N) | Male 13/23 | |

| Ethnicity (n) | 19 Caucasian, 3 Asian, 1 African American | |

| Specialty | Family practice/internal medicine: 5 | |

| Adult subspecialist: 4 | ||

| Pediatrics/child subspecialist: 6 | ||

| Surgical specialty: 3 | ||

| Neurology/anesthesia/emergency medicine/radiation oncology: 5 | ||

| Practice type | Clinician: 10 | Clinician/researcher: 5 |

| Clinician/educator: 5 | Clinician/administrator: 3 | |

| Practice location | University hospital: 11 | |

| Community hospital: 2 | ||

| Private practice: 9 | ||

| Research/nonpracticing: 1 | ||

| Tumor type | Breast: 5; renal: 4; prostate: 5; lymphoma: 3; colon: 2 (1 participant had 2 cancers) | |

| Bone/brain/larynx/head & neck/thyroid: 1 each | ||

| Illness stage | Disease-free >5 years: 9 | |

| Disease-free >6 months: 5 | ||

| Disease-free <6 months: 4 | ||

| In treatment: 2 | ||

| Metastatic/rapidly progressive disease: 3 | ||

The nature of self-doctoring What is self-doctoring and when does it occur?

The participants did not identify a discrete activity or group of activities that constituted self-doctoring (Table 2). Some activities were obvious because they required privileges restricted to medical personnel—for example, ordering one’s own abdominal computed tomography scan. Other activities were less obvious because they could be performed by any patient—such as treating oneself for a minor illness like low back pain.

Should you doctor yourself? Whereas only 1 participant recommended self-doctoring, the rest were more or less strongly opposed to the practice. Despite this stance, most participants were able to identify instances during which they did doctor themselves. Sometimes they doctored themselves without acknowledging this activity as doctoring.

EF: Do you ever feel like you do anything where you doctor yourself?

PARTICIPANT: No I don’t think so . . . I’ve never had a primary care physician, which is probably a mistake because I tell all my patients they should have one.

EF: How did you get your PSAs [prostate-specific antigen]?

PARTICIPANT: I would just go down and get my blood done myself.

EF: So would you say that is an example of being your own doctor?

PARTICIPANT: Yeah, I suppose it is to some degree!

Reframing the question: from self-doctoring to health care-seeking strategies. Although our questions were about self-doctoring, participants spoke less about self-doctoring and more about their strategy for obtaining health care. This concept of health care-seeking strategies accounted for all of the various methods that participants used to obtain health care, of which self-doctoring was one.

TABLE 2

Subtle ways in which participants doctored themselves

| Decide when to seek or not seek care |

| Did not get alarmed about neck mass because she knew what cancer felt like |

| Did not call physician with most things because they are “silly” |

| Did not go to physician until family member insisted |

| Establish a diagnosis |

| Broke own bad news by going into the hospital computer on a weekend |

| Diagnosed self as depressed but that it was subclinical |

| Went directly to a gastroenterologist to evaluate abdominal pain |

| Called physician with a diagnosis, not a problem |

| Learn about illness |

| Became an expert in own disease |

| Called an expert colleague at another institution to critique care |

| Influence care decisions |

| Rejected a recommendation that did not coincide with medical training |

| Decided on a specific surgical procedure, then found an oncologist |

| Chose a physician who she knew would go along with whatever she wanted |

| Assumed he didn’t need a second opinion because he was a physician |

| Get treatment |

| Managed only illnesses in her own specialty |

| Followed own Dilantin levels |

The continuum of health care-seeking strategies

The following examples illustrate 3 health care-seeking strategies. When viewed together, these strategies create a continuum ranging between the roles of physician and patient. The following categories are not intended to be mutually exclusive, but to indicate an individual participant’s emphasized role. We referred to strategies that emphasized the physician role as PHYSICIAN-patient, here exemplified by this internist who had more than 40 years of experience in clinical practice.

One evening I felt a mass in my right lower quadrant. I figured I had a little hematoma—I couldn’t see anything, but I was pretty asymptomatic and by chance felt [the mass]. I watched it for maybe a week or so and it didn’t seem to change. I did a couple of routine blood tests and my CBC and Chem-20 profile were okay. But then when [the mass] didn’t go down, I asked one of my partners to feel it. He said “yes, I can feel a mass—you’d better look into it.” I didn’t see a doctor—just a curbside-type thing. So then I set up a CT scan, I got a CE antigen, and I just did this on my own, and the CT scan showed a mass in the appendiceal area and the CE antigen was up a little bit. I guess I went right to my surgeon!

At the other end of the continuum, this middleaged pediatric subspecialist represents those physicians whose health care-seeking strategies were based on their roles as patients. We labeled this strategy physician-PATIENT, emphasizing the patient role.

You know, I think that a physician diagnosed with cancer is like any person diagnosed with cancer. Their first concern has nothing to do with their careers. I think the hardest thing about being a physician-patient is that you hate to bother your doctors. Or you want to sort of “call your doctor with the answer” instead of just asking questions. I think you sort of feel like sometimes that you should be able to somehow know whether [your] symptom is related to metastatic disease without having to ask, “Should I be worried about this or not?” Physicians have the same fears and difficulties as anyone else does and need to give themselves permission to act like a normal patient.

This next physician, a medical subspecialist who had recently undergone bilateral mastectomy for stage I breast cancer, falls somewhere in the middle of this continuum. We labeled this approach Physician-Patient, signifying the incorporation of both roles into her health care-seeking strategy.

This breast mass was discovered by my gynecologist but he told me, don’t worry—it’s a fibroadenoma. It was small, not really moveable, so I didn’t listen to him. I went to a surgeon. I wouldn’t say I doctored myself just because I didn’t necessarily listen to my physician. It didn’t make sense from my medical training, so I did what made sense—I can listen to those doctors’ advice, but I use my own judgment.

Advantages of being a physician-patient: convenience and control. Physicians recognized definite advantages afforded by their status, mostly related to added convenience in navigating through the system and scheduling appointments, and being able to control many aspects of their care. This specialist in infectious disease with metastatic cancer illustrates the importance of convenience and control in explaining why she often relied on self-doctoring.

I think idealistically you should never be your own doctor, but realistically I think I can accomplish more faster without interrupting the doctor’s schedule. A couple of weeks ago I started spiking fevers but I had no symptoms of any kind…. After the third day I thought, “I bet this is tumor fever!” So I went out and bought Naprosyn and I was afebrile the next morning…. Now I guess there is a small chance I have an abscess somewhere, but I think I can obviate a lot of workup that my physician is more obligated to do than I am, medico-legally … I am sure there are control issues because we all like control and I am sure I like the control and the convenience.

Disadvantages of being a physician-patient: denying yourself the opportunity to receive support; lack of objectivity; delaying care. In talking about the disadvantages of their strategies, physicians invariably referred to a previous negative experience. This young pediatrician with a large retroperitoneal mass described how she learned of her computed tomography scan results.

More insidious is the potential loss of objectivity that can occur when one’s own health is at stake. For example, a pediatric subspecialist with lymphoma described how she rationalized not bringing the enlarged lymph nodes in her neck to medical attention by telling herself that she “knew what cancer felt like.”

Advantages of being a physician-patient: trusting one’s care to others; relinquishing control; benefiting from the expertise and support of other physicians. Physicians who relied more on their physicians and less on self-doctoring approached control from the perspective of “letting go.” This emergency medicine specialist explains why he would rather trust his physician’s expertise than his own.

Find doctors you trust and listen to them because they’re the experts. The same way you’re the expert to your patients, the patients you care for. In some real sense, relinquish control. Give control to somebody else and even for nonphysician patients it’s very difficult but for physician-patients I think it’s one of the most difficult things but you have to do this. You have to trust yourself to someone else.

Disadvantages of being a physician-patient: being too trusting. This physician-patient describes adopting a more passive stance toward his health care in order to “be a good patient.” The result was that his Hodgkin’s disease was not diagnosed until 18 months after his initial biopsy.

By adopting that stance, I might have done myself a disservice. Our lives would have been very different had I questioned more aggressively the use of a needle biopsy because the pathologist here said, “You know, that’s an absolutely foolish inept way to look for lymphoma.” So in some ways the strategy backfired a bit.… But I really trusted their judgment.

Discussion

The attitudes and experiences of the study participants paralleled the medical literature: all but 1 recommended against self-doctoring, yet almost all were able to identify situations in which they did doctor themselves. Our findings show that participants’ health care-seeking strategies can be identified along a continuum ranging between the roles of physician and patient ( Figure 1 ). Whereas previous literature on physician-patients has characterized their situation as “role-reversal,”16,19,27 our findings suggest that physicians assume both roles depending on circumstances, influenced by their desire for control and degree of trust.

Trusting health care may be particularly difficult for physician-patients.2,3,27 In our study, participants at the “physician” end of the continuum were reluctant to “let go” of control over care, especially care they did not trust. They valued the convenience and time saved when they did things themselves and felt less need for support from their professional caregivers. These physicians did not consciously set out to doctor themselves. Instead, they simply used the expertise and status of their physician role to take care of themselves in the same way they might take care of a patient.

At the “patient” end of the health care-seeking continuum, participants approached their own health care as they thought a patient should. They tended not to be as involved with the details of their care, felt less pressure to be an expert in their own illness, and wanted their doctor to play an active role in medical decisions. They frequently emphasized the importance of being able to trust their care to another person and letting go of the need to be in control of their care. They valued the relationships with their physicians and appreciated the support these relationships provided.

Negative experiences invariably changed participants’ attitudes and where they were identified on the continuum. Both roles included unanticipated pitfalls, particularly for participants who adhered rigidly to either end of the continuum.

This study had important limitations. We recruited only physician-patients with cancer from a single institution and our sample was skewed toward survivors and presumably toward individuals who were comfortable talking about their experiences. Moreover, we replied on a convenience sample of patient-physicians identified by their specialists. Thus, the transferability of out findings ma be limited. Finally, our data captured the perspective of only the “physician-patient”—we did not interview their physicians. Nonetheless, we believe this provides robust new insights into physicians self-doctoring behaviors in the face of a serious, life-threatening illness.

Our findings make sense of the apparent mismatch between expert recommendations and physicians’ stated beliefs on one side, and physicians’ reported activities on the other. Rather than warning physicians not to doctor themselves, we advocate trying to focus on what is important: obtaining and providing good care ( Table 3 ). These questions are derived from 1 or more participating physician-patients’ experiences. In this way, we hope that readers might benefit from our participants’ experiences.

TABLE 3

Questions for physicians to ask themselves when seeking health care

| Are you responding more like a patient or more like a physician? Why? |

| If you are responding more like a physician: |

| Is it out of habit or convenience? |

| Is it because you don’t trust your doctors or health system (or because they are untrustworthy)? |

| Are you using your role as physician to shield yourself from painful or overwhelming realities? |

| Was an error made, or were you not getting the care you thought necessary? |

| AND |

| Do you have, or can you get, the necessary expertise to deal with your illness? |

| Are you too emotionally involved to be objective (and how would you recognize this problem)? |

| Do you, at minimum, have a physician you can trust and collaborate with—one with whom you would feel comfortable being a patient? |

| Are you getting the psychosocial support that may help you? |

| Are your nonmedical needs (rest, recreation, time off, decreased responsibilities at work) being met? |

| Are you getting the care you would want a patient in your position to receive? |

| If you are responding more like a patient: |

| Is it because you want to be “a good patient”? |

| Is it because you want someone else to make your decisions for you? |

| AND |

| Do you trust your professional caregivers and health care system? (And is that trust well founded?) |

| Are you ignoring your medical training or instincts because you do not want to offend? |

| Are you getting the information that you need (especially informed consent)? |

| Are you getting the psychosocial support you need? |

| Are your nonmedical needs (rest, recreation, time off, decreased responsibilities at work) being met? |

| Is the care you are getting consistent with the standard of care? |

| If it is not, do you understand why? |

| Are you getting the respect you would want a patient in your position to receive? |

| In either case: Would you be better off responding more like a patient, or more like a physician? |

FIGURE 1

Physician-patient continuum

Acknowledgments

Dr Carrese was a Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar when this work was conducted. This work was largely completed while Drs Fromme and Hebert were fellows in the Division of General Internal Medicine, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. It was presented in abstract form at the 24th Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, San Diego, California in May 2001 and was funded by a grant from the Kenneth B. Schwartz Center, Boston, Mass.

Corresponding author

Erik K. Fromme, MD, Division of General Medicine and Geriatrics, L475, Oregon Health and Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road, Portland, OR 97239-3098. E-mail: [email protected].

- Physician “self-doctoring” may have benefits, but it may also cause unanticipated psychological and medical problems. When faced with a serious medical problem, carefully assess both the potential positive and negative aspects of such behavior.

Background: Self-doctoring is providing oneself care normally delivered by a professional caregiver. Expert authors warn physicians not to self-doctor, yet cross-sectional studies document that physicians frequently do. Explanations for this disparity remain speculative.

Objective: To better understand the circumstances when physicians did and did not doctor themselves and the reasoning behind their actions.

Design: Qualitative semistructured interview study of 23 physician-patients currently or previously treated for cancer.

Results: Participants had multiple opportunities to doctor themselves (or not) at each stage of illness. Only 1 physician recommended self-doctoring, although most reported having done so, sometimes without realizing it. Participants’ approaches to their own health care created a continuum ranging between typical physician and patient roles. Participants emphasizing their physician role approached their health care as they would approach the care of their own patients, preferring convenience and control of their care to support from professional caregivers. Participants emphasizing their role as patient approached their health care as they thought a patient should, preferring to rely less on their own abilities and more on their providers, whose support they valued. Most participants balanced both roles depending on their experiences and basic issues of trust and control. Importantly, subjects at both ends of the continuum reported unanticipated pitfalls of their approach.

Conclusion: Our findings showed that participants’ health care-seeking strategies fell on a continuum that ranged from a purely patient role to one that centered on physician activities. Participants identified problems associated with overdependence on either role, suggesting that a balanced approach, one that uses the advantages of both physician and patient roles, has merit.

The physician who doctors himself has a fool for a patient.

—Sir William Osler

The consistent message in the medical literature, beginning with Osler, has been that physicians should not doctor themselves.1-9 Despite this belief, a number of cross-sectional studies suggest that at best only 50% of physicians even have a personal physician1,8-13 and that between 42% and 82% of physicians doctor themselves in some fashion.1,6,8,12

Becoming a competent physician does not automatically make one a competent patient.14,15 In fact, physicians are allegedly the “very worst patients.”15 Physicians are expected to understand and empathize with the patient’s perspective, yet most authors have maintained that physicians tend to avoid, deny, or reject patient-hood,2,3,5,11,13,14,16-22 and even the susceptibility to illness.23

Given the high prevalence of self-doctoring behavior among physician-patients, we sought to further explore seriously ill physicians’ experiences with self-doctoring. Specifically, we wanted to know if they doctored themselves and, if so, when, why, and with what outcome.

Methods

Design

For this qualitative study, approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board, we used semistructured in-depth interviews.

Study population and sampling

A convenience sample of physicians who had been treated for cancer during or after their medical training was identified by clinicians in the divisions of oncology and radiation oncology at our institution. Of 38 physicians contacted, 25 agreed to participate; however, 2 subjects died before their interview could be arranged. Enrollment continued until no new concepts were identified, also called the point of theoretical saturation.24

Data collection

We based the interview questions on themes extracted from a literature search that identified 5 books, 26 articles, and 3 videotapes. (These references are available online as Table W1.) Interviews lasted approximately 1.5 hours. The interviewer (E.F.) started by asking subjects to tell the story of how they learned of their cancer and progressed to more focused questions about whether they acted as their own doctor and why. All interviews were taped and transcribed, and their accuracy was verified by listening to the audiotape.

Analysis. Two coders (E.F. and R.H.) independently coded all 23 transcripts. In case of disagreement, the coders achieved consensus through discussion and used this information to refine the boundaries of each theme.

Working together, we created a comprehensive coding scheme by arranging data into logical categories of themes using the strategies of textual analysis and codebook development described by Crabtree and Miller.25 The work by Crabtree and Miller addressed the theme “health care-seeking behaviors and strategies” and its associated codes developed using an “editing-style analysis” consistent with the constant comparative method in the Grounded Theory tradition.26

Trustworthiness. To ensure trustworthiness, we mailed an 11-item summary of the main points to the 21 surviving participants as the analysis neared completion. We asked them to review the main points of our study, indicate whether they agreed or disagreed (with no response indicating agreement), and add any clarifying comments they felt appropriate. This information was used to clarify and further develop themes.

RESULTS

Our sample was predominately Caucasian and represented a diversity of gender, specialty, and participant characteristics (Table 1).

TABLE 1

Participant characteristics (N=23)

| Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean and median=55, range=28–83 | |

| Years in practice | Mean=22.4, median=19, range=0–56 (1 resident, 1 fellow, 2 retired) | |

| Sex (n/N) | Male 13/23 | |

| Ethnicity (n) | 19 Caucasian, 3 Asian, 1 African American | |

| Specialty | Family practice/internal medicine: 5 | |

| Adult subspecialist: 4 | ||

| Pediatrics/child subspecialist: 6 | ||

| Surgical specialty: 3 | ||

| Neurology/anesthesia/emergency medicine/radiation oncology: 5 | ||

| Practice type | Clinician: 10 | Clinician/researcher: 5 |

| Clinician/educator: 5 | Clinician/administrator: 3 | |

| Practice location | University hospital: 11 | |

| Community hospital: 2 | ||

| Private practice: 9 | ||

| Research/nonpracticing: 1 | ||

| Tumor type | Breast: 5; renal: 4; prostate: 5; lymphoma: 3; colon: 2 (1 participant had 2 cancers) | |

| Bone/brain/larynx/head & neck/thyroid: 1 each | ||

| Illness stage | Disease-free >5 years: 9 | |

| Disease-free >6 months: 5 | ||

| Disease-free <6 months: 4 | ||

| In treatment: 2 | ||

| Metastatic/rapidly progressive disease: 3 | ||

The nature of self-doctoring What is self-doctoring and when does it occur?

The participants did not identify a discrete activity or group of activities that constituted self-doctoring (Table 2). Some activities were obvious because they required privileges restricted to medical personnel—for example, ordering one’s own abdominal computed tomography scan. Other activities were less obvious because they could be performed by any patient—such as treating oneself for a minor illness like low back pain.

Should you doctor yourself? Whereas only 1 participant recommended self-doctoring, the rest were more or less strongly opposed to the practice. Despite this stance, most participants were able to identify instances during which they did doctor themselves. Sometimes they doctored themselves without acknowledging this activity as doctoring.

EF: Do you ever feel like you do anything where you doctor yourself?

PARTICIPANT: No I don’t think so . . . I’ve never had a primary care physician, which is probably a mistake because I tell all my patients they should have one.

EF: How did you get your PSAs [prostate-specific antigen]?

PARTICIPANT: I would just go down and get my blood done myself.

EF: So would you say that is an example of being your own doctor?

PARTICIPANT: Yeah, I suppose it is to some degree!

Reframing the question: from self-doctoring to health care-seeking strategies. Although our questions were about self-doctoring, participants spoke less about self-doctoring and more about their strategy for obtaining health care. This concept of health care-seeking strategies accounted for all of the various methods that participants used to obtain health care, of which self-doctoring was one.

TABLE 2

Subtle ways in which participants doctored themselves

| Decide when to seek or not seek care |

| Did not get alarmed about neck mass because she knew what cancer felt like |

| Did not call physician with most things because they are “silly” |

| Did not go to physician until family member insisted |

| Establish a diagnosis |

| Broke own bad news by going into the hospital computer on a weekend |

| Diagnosed self as depressed but that it was subclinical |

| Went directly to a gastroenterologist to evaluate abdominal pain |

| Called physician with a diagnosis, not a problem |

| Learn about illness |

| Became an expert in own disease |

| Called an expert colleague at another institution to critique care |

| Influence care decisions |

| Rejected a recommendation that did not coincide with medical training |

| Decided on a specific surgical procedure, then found an oncologist |

| Chose a physician who she knew would go along with whatever she wanted |

| Assumed he didn’t need a second opinion because he was a physician |

| Get treatment |

| Managed only illnesses in her own specialty |

| Followed own Dilantin levels |

The continuum of health care-seeking strategies

The following examples illustrate 3 health care-seeking strategies. When viewed together, these strategies create a continuum ranging between the roles of physician and patient. The following categories are not intended to be mutually exclusive, but to indicate an individual participant’s emphasized role. We referred to strategies that emphasized the physician role as PHYSICIAN-patient, here exemplified by this internist who had more than 40 years of experience in clinical practice.

One evening I felt a mass in my right lower quadrant. I figured I had a little hematoma—I couldn’t see anything, but I was pretty asymptomatic and by chance felt [the mass]. I watched it for maybe a week or so and it didn’t seem to change. I did a couple of routine blood tests and my CBC and Chem-20 profile were okay. But then when [the mass] didn’t go down, I asked one of my partners to feel it. He said “yes, I can feel a mass—you’d better look into it.” I didn’t see a doctor—just a curbside-type thing. So then I set up a CT scan, I got a CE antigen, and I just did this on my own, and the CT scan showed a mass in the appendiceal area and the CE antigen was up a little bit. I guess I went right to my surgeon!

At the other end of the continuum, this middleaged pediatric subspecialist represents those physicians whose health care-seeking strategies were based on their roles as patients. We labeled this strategy physician-PATIENT, emphasizing the patient role.

You know, I think that a physician diagnosed with cancer is like any person diagnosed with cancer. Their first concern has nothing to do with their careers. I think the hardest thing about being a physician-patient is that you hate to bother your doctors. Or you want to sort of “call your doctor with the answer” instead of just asking questions. I think you sort of feel like sometimes that you should be able to somehow know whether [your] symptom is related to metastatic disease without having to ask, “Should I be worried about this or not?” Physicians have the same fears and difficulties as anyone else does and need to give themselves permission to act like a normal patient.

This next physician, a medical subspecialist who had recently undergone bilateral mastectomy for stage I breast cancer, falls somewhere in the middle of this continuum. We labeled this approach Physician-Patient, signifying the incorporation of both roles into her health care-seeking strategy.

This breast mass was discovered by my gynecologist but he told me, don’t worry—it’s a fibroadenoma. It was small, not really moveable, so I didn’t listen to him. I went to a surgeon. I wouldn’t say I doctored myself just because I didn’t necessarily listen to my physician. It didn’t make sense from my medical training, so I did what made sense—I can listen to those doctors’ advice, but I use my own judgment.

Advantages of being a physician-patient: convenience and control. Physicians recognized definite advantages afforded by their status, mostly related to added convenience in navigating through the system and scheduling appointments, and being able to control many aspects of their care. This specialist in infectious disease with metastatic cancer illustrates the importance of convenience and control in explaining why she often relied on self-doctoring.

I think idealistically you should never be your own doctor, but realistically I think I can accomplish more faster without interrupting the doctor’s schedule. A couple of weeks ago I started spiking fevers but I had no symptoms of any kind…. After the third day I thought, “I bet this is tumor fever!” So I went out and bought Naprosyn and I was afebrile the next morning…. Now I guess there is a small chance I have an abscess somewhere, but I think I can obviate a lot of workup that my physician is more obligated to do than I am, medico-legally … I am sure there are control issues because we all like control and I am sure I like the control and the convenience.

Disadvantages of being a physician-patient: denying yourself the opportunity to receive support; lack of objectivity; delaying care. In talking about the disadvantages of their strategies, physicians invariably referred to a previous negative experience. This young pediatrician with a large retroperitoneal mass described how she learned of her computed tomography scan results.

More insidious is the potential loss of objectivity that can occur when one’s own health is at stake. For example, a pediatric subspecialist with lymphoma described how she rationalized not bringing the enlarged lymph nodes in her neck to medical attention by telling herself that she “knew what cancer felt like.”

Advantages of being a physician-patient: trusting one’s care to others; relinquishing control; benefiting from the expertise and support of other physicians. Physicians who relied more on their physicians and less on self-doctoring approached control from the perspective of “letting go.” This emergency medicine specialist explains why he would rather trust his physician’s expertise than his own.

Find doctors you trust and listen to them because they’re the experts. The same way you’re the expert to your patients, the patients you care for. In some real sense, relinquish control. Give control to somebody else and even for nonphysician patients it’s very difficult but for physician-patients I think it’s one of the most difficult things but you have to do this. You have to trust yourself to someone else.

Disadvantages of being a physician-patient: being too trusting. This physician-patient describes adopting a more passive stance toward his health care in order to “be a good patient.” The result was that his Hodgkin’s disease was not diagnosed until 18 months after his initial biopsy.

By adopting that stance, I might have done myself a disservice. Our lives would have been very different had I questioned more aggressively the use of a needle biopsy because the pathologist here said, “You know, that’s an absolutely foolish inept way to look for lymphoma.” So in some ways the strategy backfired a bit.… But I really trusted their judgment.

Discussion

The attitudes and experiences of the study participants paralleled the medical literature: all but 1 recommended against self-doctoring, yet almost all were able to identify situations in which they did doctor themselves. Our findings show that participants’ health care-seeking strategies can be identified along a continuum ranging between the roles of physician and patient ( Figure 1 ). Whereas previous literature on physician-patients has characterized their situation as “role-reversal,”16,19,27 our findings suggest that physicians assume both roles depending on circumstances, influenced by their desire for control and degree of trust.

Trusting health care may be particularly difficult for physician-patients.2,3,27 In our study, participants at the “physician” end of the continuum were reluctant to “let go” of control over care, especially care they did not trust. They valued the convenience and time saved when they did things themselves and felt less need for support from their professional caregivers. These physicians did not consciously set out to doctor themselves. Instead, they simply used the expertise and status of their physician role to take care of themselves in the same way they might take care of a patient.

At the “patient” end of the health care-seeking continuum, participants approached their own health care as they thought a patient should. They tended not to be as involved with the details of their care, felt less pressure to be an expert in their own illness, and wanted their doctor to play an active role in medical decisions. They frequently emphasized the importance of being able to trust their care to another person and letting go of the need to be in control of their care. They valued the relationships with their physicians and appreciated the support these relationships provided.

Negative experiences invariably changed participants’ attitudes and where they were identified on the continuum. Both roles included unanticipated pitfalls, particularly for participants who adhered rigidly to either end of the continuum.

This study had important limitations. We recruited only physician-patients with cancer from a single institution and our sample was skewed toward survivors and presumably toward individuals who were comfortable talking about their experiences. Moreover, we replied on a convenience sample of patient-physicians identified by their specialists. Thus, the transferability of out findings ma be limited. Finally, our data captured the perspective of only the “physician-patient”—we did not interview their physicians. Nonetheless, we believe this provides robust new insights into physicians self-doctoring behaviors in the face of a serious, life-threatening illness.

Our findings make sense of the apparent mismatch between expert recommendations and physicians’ stated beliefs on one side, and physicians’ reported activities on the other. Rather than warning physicians not to doctor themselves, we advocate trying to focus on what is important: obtaining and providing good care ( Table 3 ). These questions are derived from 1 or more participating physician-patients’ experiences. In this way, we hope that readers might benefit from our participants’ experiences.

TABLE 3

Questions for physicians to ask themselves when seeking health care

| Are you responding more like a patient or more like a physician? Why? |

| If you are responding more like a physician: |

| Is it out of habit or convenience? |

| Is it because you don’t trust your doctors or health system (or because they are untrustworthy)? |

| Are you using your role as physician to shield yourself from painful or overwhelming realities? |

| Was an error made, or were you not getting the care you thought necessary? |

| AND |

| Do you have, or can you get, the necessary expertise to deal with your illness? |

| Are you too emotionally involved to be objective (and how would you recognize this problem)? |

| Do you, at minimum, have a physician you can trust and collaborate with—one with whom you would feel comfortable being a patient? |

| Are you getting the psychosocial support that may help you? |

| Are your nonmedical needs (rest, recreation, time off, decreased responsibilities at work) being met? |

| Are you getting the care you would want a patient in your position to receive? |

| If you are responding more like a patient: |

| Is it because you want to be “a good patient”? |

| Is it because you want someone else to make your decisions for you? |

| AND |

| Do you trust your professional caregivers and health care system? (And is that trust well founded?) |

| Are you ignoring your medical training or instincts because you do not want to offend? |

| Are you getting the information that you need (especially informed consent)? |

| Are you getting the psychosocial support you need? |

| Are your nonmedical needs (rest, recreation, time off, decreased responsibilities at work) being met? |

| Is the care you are getting consistent with the standard of care? |

| If it is not, do you understand why? |

| Are you getting the respect you would want a patient in your position to receive? |

| In either case: Would you be better off responding more like a patient, or more like a physician? |

FIGURE 1

Physician-patient continuum

Acknowledgments

Dr Carrese was a Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar when this work was conducted. This work was largely completed while Drs Fromme and Hebert were fellows in the Division of General Internal Medicine, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. It was presented in abstract form at the 24th Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine, San Diego, California in May 2001 and was funded by a grant from the Kenneth B. Schwartz Center, Boston, Mass.

Corresponding author

Erik K. Fromme, MD, Division of General Medicine and Geriatrics, L475, Oregon Health and Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Road, Portland, OR 97239-3098. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Toyry S, Rasanen K, Kujala S, et al. Self-reported health, illness and self-care among Finnish physicians: a national survey. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1079-1085.

2. Allibone A. Who treats the doctor? Practitioner. 1990;234:984-987.

3. Miller MN, McGowen KR. The painful truth: physicians are not invincible. South Med J. 2000;93:966-973.

4. Budge A, Dickstein E. The doctor as patient: bioethical dilemmas reflected in literary narratives. Lit Med. 1988;7:132-137.

5. Rogers T. Barriers to the doctor as patient role. A cultural construct. Aust Fam Physician. 1998;27:1009-1013.

6. Waldron HA. Sickness in the medical profession. Ann Occup Hyg. 1996;40:391-396.

7. Waldron HA. Medical advice for sick physicians. Lancet. 1996;347:1558-1559.

8. Wines AP, Khadra MH, Wines RD. Surgeon, don’t heal thyself: a study of the health of Australian urologists. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998;68:778-781.

9. Pullen D, Lonie CE, Lyle DM, Cam DE, Doughty MV. Medical care of doctors. Med J Aust. 1995;162:481,-484.

10. Allibone A, Oakes D, Shannon HS. The health and health care of doctors. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1981;31:728-734.

11. Schwartz JS, Lewis CE, Clancy C, Kinosian MS, Radany MH, Koplan JP. Internists’ practices in health promotion and disease prevention. A survey. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:46-53.

12. Rosen IM, Christie JD, Bellini LM, Asch DA. Health and health care among housestaff in four U.S. internal medicine residency programs. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:116-121.

13. Kahn KL, Goldberg RJ, DeCosimo D, Dalen JE. Health maintenance activities of physicians and nonphysicians. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:2433-2436.

14. Robbins GF, MacDonald MC, Pack GT. Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of physicians with cancer. Cancer 1953;6:624-626.

15. Anonymous [proverb] Strauss’ Familiar Medical Quotations. New York, NY: Little, Brown; 1968;415b.-

16. Spiro HM, Mandell H. When doctors get sick. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:152-154.

17. Bittker TE. Reaching out to the depressed physician. JAMA. 1976;236:1713-1716.

18. Lampert PH. On the other side of the bed sheets. When the doctor is the patient. Minn Med. 1991;74(11):14-19.

19. Glass GS. Incomplete role reversal: the dilemma of hospitalization for the professional peer. Psychiatry. 1975;38:132-144.

20. Ellard J. The disease of being a doctor. Med J Aust. 1974;2:318-323.

21. Vaillant GE, Sobowale NC, McArthur C. Some psychologic vulnerabilities of physicians. N Engl J Med. 1972;287:372-375.

22. Thompson WT, Cupples ME, Sibbett CH, Skan DI, Bradley T. Challenge of culture, conscience, and contract to general practitioners’ care of their own health: qualitative study. BMJ. 2001;323:728-731.

23. Gold N. The doctor, his illness and the patient. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1972;6:209-213.

24. Kuzel A. Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In: Crabtree B, Miller W, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1992;31-44.

25. Crabtree B, Miller W. A template approach to text analysis: developing and using codebooks. In: Crabtree B, Miller W, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1992;93-109.

26. Glaser B, Strauss A. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine De Gruyter; 1967;101-115.

27. Edelstein EL, Baider L. Role reversal: when doctors become patients. Psychiatria Clin (Basel). 1982;15:177-183.

1. Toyry S, Rasanen K, Kujala S, et al. Self-reported health, illness and self-care among Finnish physicians: a national survey. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1079-1085.

2. Allibone A. Who treats the doctor? Practitioner. 1990;234:984-987.

3. Miller MN, McGowen KR. The painful truth: physicians are not invincible. South Med J. 2000;93:966-973.

4. Budge A, Dickstein E. The doctor as patient: bioethical dilemmas reflected in literary narratives. Lit Med. 1988;7:132-137.

5. Rogers T. Barriers to the doctor as patient role. A cultural construct. Aust Fam Physician. 1998;27:1009-1013.

6. Waldron HA. Sickness in the medical profession. Ann Occup Hyg. 1996;40:391-396.

7. Waldron HA. Medical advice for sick physicians. Lancet. 1996;347:1558-1559.

8. Wines AP, Khadra MH, Wines RD. Surgeon, don’t heal thyself: a study of the health of Australian urologists. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998;68:778-781.

9. Pullen D, Lonie CE, Lyle DM, Cam DE, Doughty MV. Medical care of doctors. Med J Aust. 1995;162:481,-484.

10. Allibone A, Oakes D, Shannon HS. The health and health care of doctors. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1981;31:728-734.

11. Schwartz JS, Lewis CE, Clancy C, Kinosian MS, Radany MH, Koplan JP. Internists’ practices in health promotion and disease prevention. A survey. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:46-53.

12. Rosen IM, Christie JD, Bellini LM, Asch DA. Health and health care among housestaff in four U.S. internal medicine residency programs. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:116-121.

13. Kahn KL, Goldberg RJ, DeCosimo D, Dalen JE. Health maintenance activities of physicians and nonphysicians. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:2433-2436.

14. Robbins GF, MacDonald MC, Pack GT. Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of physicians with cancer. Cancer 1953;6:624-626.

15. Anonymous [proverb] Strauss’ Familiar Medical Quotations. New York, NY: Little, Brown; 1968;415b.-

16. Spiro HM, Mandell H. When doctors get sick. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:152-154.

17. Bittker TE. Reaching out to the depressed physician. JAMA. 1976;236:1713-1716.

18. Lampert PH. On the other side of the bed sheets. When the doctor is the patient. Minn Med. 1991;74(11):14-19.

19. Glass GS. Incomplete role reversal: the dilemma of hospitalization for the professional peer. Psychiatry. 1975;38:132-144.

20. Ellard J. The disease of being a doctor. Med J Aust. 1974;2:318-323.

21. Vaillant GE, Sobowale NC, McArthur C. Some psychologic vulnerabilities of physicians. N Engl J Med. 1972;287:372-375.

22. Thompson WT, Cupples ME, Sibbett CH, Skan DI, Bradley T. Challenge of culture, conscience, and contract to general practitioners’ care of their own health: qualitative study. BMJ. 2001;323:728-731.

23. Gold N. The doctor, his illness and the patient. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1972;6:209-213.

24. Kuzel A. Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In: Crabtree B, Miller W, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1992;31-44.

25. Crabtree B, Miller W. A template approach to text analysis: developing and using codebooks. In: Crabtree B, Miller W, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1992;93-109.

26. Glaser B, Strauss A. Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine De Gruyter; 1967;101-115.

27. Edelstein EL, Baider L. Role reversal: when doctors become patients. Psychiatria Clin (Basel). 1982;15:177-183.